.gif)

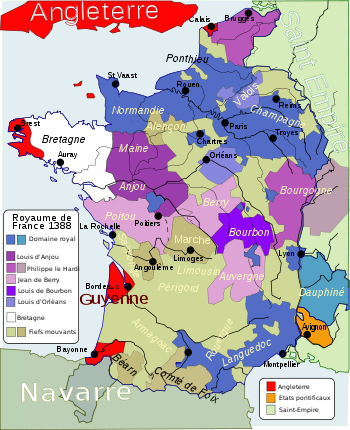

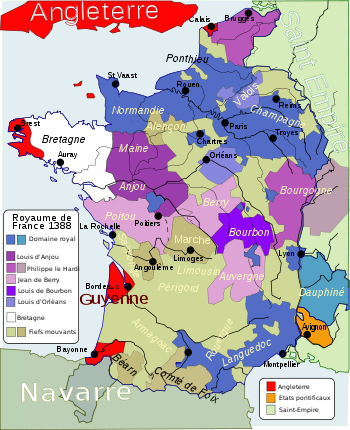

Hundred Years' War (1369-1389)

Encyclopedia

The Caroline War was the second phase of the Hundred Years' War

between France

and England

, following the Edwardian War

. It was so-named after Charles V of France

, who resumed the war after the Treaty of Brétigny

(signed 1360). In May 1369, the Black Prince

, son of Edward III of England

, refused an illegal summons from the French king demanding he come to Paris

and Charles responded by declaring war. He immediately set out to reverse the territorial losses imposed at Brétigny and he was largely successful in his lifetime. His less capable successor, Charles VI

, made peace with the less capable son of the Black Prince, Richard II

, in 1389. This truce was extended many times until the war was resumed

in 1415.

in 1364, John and his heirs eventually reconciled with the French kings. The War of the Breton Succession ended in favour of the English, but gave them no great advantage. In fact, the French received the benefit of improved generalship in the person of the Breton commander Bertrand du Guesclin

, who, leaving Brittany, entered the service of Charles and became one of his most successful generals.

At about the same time, a war in Spain occupied the Black Prince's efforts from 1366. The Castilian Civil War

pitted Pedro the Cruel

, whose daughters Constance and Isabella were married to the Black Prince's brothers John of Gaunt and Edmund of Langley, against Henry of Trastámara. In 1369, with the support of Du Guesclin, Henry deposed Pedro to become Henry II of Castile. He then went to war with England, which was allied with Portugal

.

of Poitou

, John Chandos

, was killed at the bridge at Lussac-les-Châteaux

. The loss of this commander was a significant blow to the English. Jean III de Grailly

, the captal de Buch

, was also captured and locked up by Charles, who did not feel bound by "outdated" chivalry. Du Guesclin continued a series of careful campaigns, avoiding major English field forces, but capturing town after town, including Poitiers

in 1372 and Bergerac

in 1377. Du Guesclin, who according to chronicler Jean Froissart

, had advised the French king not to engage the English in the field, was successful in these Fabian tactics

, though in the only two major battles in which he fought, Auray

(1364) and Nájera (1367), he was on the losing side and was captured but released for ransom. The English response to Du Guesclin was to launch a series of destructive military expeditions, called chevauchée

s, in an effort at total war

to destroy the countryside and the productivity of the land. But Du Guesclin refused to be drawn into open battle. He continued his successful command of the French armies until his death in 1380.

In 1372, English dominance at sea, which had been upheld since the Battle of Sluys

, was reversed, at least in the Bay of Biscay

, by the disastrous defeat by a joint Franco-Castilian fleet at the Battle of La Rochelle

. This defeat undermined English seaborne trade and supplies and threatened their Gascon

possessions.

In 1376, the Black Prince died, and in April 1377, Edward III of England

sent his Chancellor

, Adam Houghton

, to negotiate for peace with Charles

, but when in June Edward himself died, Houghton was called home. The underaged Richard of Bordeaux

succeeded to the throne of England. It was not until Richard had been deposed by his cousin Henry Bolingbroke that the English, under the House of Lancaster

, could forcefully revive their claim to the French throne. The war nonetheless continued until the first of a series of truces was signed in 1389.

Charles V died in September 1380 and was succeeded by his underage son, Charles VI, who was placed under the joint regency of his three uncles. On his deathbed Charles V repealed the royal taxation necessary to fund the war effort. As the regents attempted to reimpose the taxation a popular revolt known as the Harelle

broke out in Rouen

. As tax collectors arrived at other French cities the revolt spread and violence broke out in Paris and most of France's other northern cities. The regency was forced to repeal the taxes to calm the situation.

Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War was a series of separate wars waged from 1337 to 1453 by the House of Valois and the House of Plantagenet, also known as the House of Anjou, for the French throne, which had become vacant upon the extinction of the senior Capetian line of French kings...

between France

Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France was one of the most powerful states to exist in Europe during the second millennium.It originated from the Western portion of the Frankish empire, and consolidated significant power and influence over the next thousand years. Louis XIV, also known as the Sun King, developed a...

and England

Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was, from 927 to 1707, a sovereign state to the northwest of continental Europe. At its height, the Kingdom of England spanned the southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain and several smaller outlying islands; what today comprises the legal jurisdiction of England...

, following the Edwardian War

Hundred Years' War (1337-1360)

The Edwardian War was the first phase of the Hundred Years' War, lasting from 1337 to 1360, from the outbreak of hostilities until the signing of the Treaty of Brétigny. This 23-year period was marked by the startling victories of Edward III of England and his son, the Black Prince, over the French...

. It was so-named after Charles V of France

Charles V of France

Charles V , called the Wise, was King of France from 1364 to his death in 1380 and a member of the House of Valois...

, who resumed the war after the Treaty of Brétigny

Treaty of Brétigny

The Treaty of Brétigny was a treaty signed on May 9, 1360, between King Edward III of England and King John II of France. In retrospect it is seen as having marked the end of the first phase of the Hundred Years' War —as well as the height of English hegemony on the Continent.It was signed...

(signed 1360). In May 1369, the Black Prince

Edward, the Black Prince

Edward of Woodstock, Prince of Wales, Duke of Cornwall, Prince of Aquitaine, KG was the eldest son of King Edward III of England and his wife Philippa of Hainault as well as father to King Richard II of England....

, son of Edward III of England

Edward III of England

Edward III was King of England from 1327 until his death and is noted for his military success. Restoring royal authority after the disastrous reign of his father, Edward II, Edward III went on to transform the Kingdom of England into one of the most formidable military powers in Europe...

, refused an illegal summons from the French king demanding he come to Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

and Charles responded by declaring war. He immediately set out to reverse the territorial losses imposed at Brétigny and he was largely successful in his lifetime. His less capable successor, Charles VI

Charles VI of France

Charles VI , called the Beloved and the Mad , was the King of France from 1380 to 1422, as a member of the House of Valois. His bouts with madness, which seem to have begun in 1392, led to quarrels among the French royal family, which were exploited by the neighbouring powers of England and Burgundy...

, made peace with the less capable son of the Black Prince, Richard II

Richard II of England

Richard II was King of England, a member of the House of Plantagenet and the last of its main-line kings. He ruled from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. Richard was a son of Edward, the Black Prince, and was born during the reign of his grandfather, Edward III...

, in 1389. This truce was extended many times until the war was resumed

Hundred Years' War (1415-1429)

The Lancastrian War was the third phase of the Anglo-French Hundred Years' War. It lasted from 1415, when Henry V of England invaded Normandy, to 1429 when English successes were reversed by the arrival of Joan of Arc. It followed a long period of peace from 1389 at end of the Caroline War...

in 1415.

Background

The reign of Charles V saw the English steadily pushed back. Although the English-backed claimant to the Duchy of Brittany, John of Montfort, defeated and killed the French claimant, Charles of Blois, at the Battle of AurayBattle of Auray

The Battle of Auray took place on 29 September 1364 at the French town of Auray. This battle was the decisive confrontation of the Breton War of Succession, a part of the Hundred Years' War....

in 1364, John and his heirs eventually reconciled with the French kings. The War of the Breton Succession ended in favour of the English, but gave them no great advantage. In fact, the French received the benefit of improved generalship in the person of the Breton commander Bertrand du Guesclin

Bertrand du Guesclin

Bertrand du Guesclin , known as the Eagle of Brittany or the Black Dog of Brocéliande, was a Breton knight and French military commander during the Hundred Years' War. He was Constable of France from 1370 to his death...

, who, leaving Brittany, entered the service of Charles and became one of his most successful generals.

At about the same time, a war in Spain occupied the Black Prince's efforts from 1366. The Castilian Civil War

Castilian Civil War

The Castilian Civil War lasted three years from 1366 to 1369. It became part of the larger conflict then raging between the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of France: the Hundred Years' War...

pitted Pedro the Cruel

Pedro of Castile

Peter , sometimes called "the Cruel" or "the Lawful" , was the king of Castile and León from 1350 to 1369. He was the son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Maria of Portugal, daughter of Afonso IV of Portugal...

, whose daughters Constance and Isabella were married to the Black Prince's brothers John of Gaunt and Edmund of Langley, against Henry of Trastámara. In 1369, with the support of Du Guesclin, Henry deposed Pedro to become Henry II of Castile. He then went to war with England, which was allied with Portugal

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

.

Twenty years of war

Just before New Year's Day 1370, the English seneschalSeneschal

A seneschal was an officer in the houses of important nobles in the Middle Ages. In the French administrative system of the Middle Ages, the sénéchal was also a royal officer in charge of justice and control of the administration in southern provinces, equivalent to the northern French bailli...

of Poitou

Poitou

Poitou was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers.The region of Poitou was called Thifalia in the sixth century....

, John Chandos

John Chandos

Sir John Chandos, Viscount of Saint-Sauveur in the Cotentin, Constable of Aquitaine, Seneschal of Poitou, KG was a medieval English knight who hailed from Radbourne Hall, Derbyshire. Chandos was a close friend of Edward, the Black Prince and a founding member and 19th Knight of the Order of the...

, was killed at the bridge at Lussac-les-Châteaux

Lussac-les-Châteaux

Lussac-les-Châteaux is a commune in the Vienne department in the Poitou-Charentes region in western France.- Prehistory :The importance of the prehistoric art at Lussac is evidenced by the presence of numerous archaeological artefacts in the Museum of National Antiquities at...

. The loss of this commander was a significant blow to the English. Jean III de Grailly

Jean III de Grailly, captal de Buch

Sir Jean III de Grailly, Captal de Buch KG , son of Jean II de Grailly, Captal de Buch, Vicomte de Benauges, and Blanch de Foix...

, the captal de Buch

Captal de Buch

Captal de Buch was an archaic feudal title in Gascony, captal from Latin capitalis "prime, chief" in the formula capitales domini or "principal lords." Buch was a strategically located town and port on the Atlantic, in the bay of Arcachon...

, was also captured and locked up by Charles, who did not feel bound by "outdated" chivalry. Du Guesclin continued a series of careful campaigns, avoiding major English field forces, but capturing town after town, including Poitiers

Poitiers

Poitiers is a city on the Clain river in west central France. It is a commune and the capital of the Vienne department and of the Poitou-Charentes region. The centre is picturesque and its streets are interesting for predominant remains of historical architecture, especially from the Romanesque...

in 1372 and Bergerac

Bergerac, Dordogne

Bergerac is a commune and a sub-prefecture of the Dordogne department in southwestern France.-Population:-Economy:The region is primarily known for wine and tobacco...

in 1377. Du Guesclin, who according to chronicler Jean Froissart

Jean Froissart

Jean Froissart , often referred to in English as John Froissart, was one of the most important chroniclers of medieval France. For centuries, Froissart's Chronicles have been recognized as the chief expression of the chivalric revival of the 14th century Kingdom of England and France...

, had advised the French king not to engage the English in the field, was successful in these Fabian tactics

Fabian strategy

The Fabian strategy is a military strategy where pitched battles and frontal assaults are avoided in favor of wearing down an opponent through a war of attrition and indirection. While avoiding decisive battles, the side employing this strategy harasses its enemy through skirmishes to cause...

, though in the only two major battles in which he fought, Auray

Battle of Auray

The Battle of Auray took place on 29 September 1364 at the French town of Auray. This battle was the decisive confrontation of the Breton War of Succession, a part of the Hundred Years' War....

(1364) and Nájera (1367), he was on the losing side and was captured but released for ransom. The English response to Du Guesclin was to launch a series of destructive military expeditions, called chevauchée

Chevauchée

A chevauchée was a raiding method of medieval warfare for weakening the enemy, focusing mainly on wreaking havoc, burning and pillaging enemy territory, in order to reduce the productivity of a region; as opposed to siege warfare or wars of conquest...

s, in an effort at total war

Total war

Total war is a war in which a belligerent engages in the complete mobilization of fully available resources and population.In the mid-19th century, "total war" was identified by scholars as a separate class of warfare...

to destroy the countryside and the productivity of the land. But Du Guesclin refused to be drawn into open battle. He continued his successful command of the French armies until his death in 1380.

In 1372, English dominance at sea, which had been upheld since the Battle of Sluys

Battle of Sluys

The decisive naval Battle of Sluys , also called Battle of l'Ecluse was fought on 24 June 1340 as one of the opening conflicts of the Hundred Years' War...

, was reversed, at least in the Bay of Biscay

Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay is a gulf of the northeast Atlantic Ocean located south of the Celtic Sea. It lies along the western coast of France from Brest south to the Spanish border, and the northern coast of Spain west to Cape Ortegal, and is named in English after the province of Biscay, in the Spanish...

, by the disastrous defeat by a joint Franco-Castilian fleet at the Battle of La Rochelle

Battle of La Rochelle

The naval Battle of La Rochelle took place on 22 and 23 June 1372 between a Castilian and French fleet commanded by the Genoese born Ambrosio Boccanegra and an English convoy commanded by John Hastings, 2nd Earl of Pembroke. The Franco-Castilian fleet had been sent to attack the English at La...

. This defeat undermined English seaborne trade and supplies and threatened their Gascon

Gascony

Gascony is an area of southwest France that was part of the "Province of Guyenne and Gascony" prior to the French Revolution. The region is vaguely defined and the distinction between Guyenne and Gascony is unclear; sometimes they are considered to overlap, and sometimes Gascony is considered a...

possessions.

In 1376, the Black Prince died, and in April 1377, Edward III of England

Edward III of England

Edward III was King of England from 1327 until his death and is noted for his military success. Restoring royal authority after the disastrous reign of his father, Edward II, Edward III went on to transform the Kingdom of England into one of the most formidable military powers in Europe...

sent his Chancellor

Lord Chancellor

The Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, or Lord Chancellor, is a senior and important functionary in the government of the United Kingdom. He is the second highest ranking of the Great Officers of State, ranking only after the Lord High Steward. The Lord Chancellor is appointed by the Sovereign...

, Adam Houghton

Adam Houghton

Adam Houghton , also known as Adam de Houghton, was Bishop of St David's from 1361 until his death and Lord Chancellor of England from 1377 to 1378....

, to negotiate for peace with Charles

Charles V of France

Charles V , called the Wise, was King of France from 1364 to his death in 1380 and a member of the House of Valois...

, but when in June Edward himself died, Houghton was called home. The underaged Richard of Bordeaux

Richard II of England

Richard II was King of England, a member of the House of Plantagenet and the last of its main-line kings. He ruled from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. Richard was a son of Edward, the Black Prince, and was born during the reign of his grandfather, Edward III...

succeeded to the throne of England. It was not until Richard had been deposed by his cousin Henry Bolingbroke that the English, under the House of Lancaster

House of Lancaster

The House of Lancaster was a branch of the royal House of Plantagenet. It was one of the opposing factions involved in the Wars of the Roses, an intermittent civil war which affected England and Wales during the 15th century...

, could forcefully revive their claim to the French throne. The war nonetheless continued until the first of a series of truces was signed in 1389.

Charles V died in September 1380 and was succeeded by his underage son, Charles VI, who was placed under the joint regency of his three uncles. On his deathbed Charles V repealed the royal taxation necessary to fund the war effort. As the regents attempted to reimpose the taxation a popular revolt known as the Harelle

Harelle

The Harelle was a revolt that occurred in the French city of Rouen in 1382 followed by the Maillotins Revolt a few days later in Paris, and numerous other revolts across France in the subsequent week. France was in the midst of the Hundred Years War, and had seen decades of warfare, widespread...

broke out in Rouen

Rouen

Rouen , in northern France on the River Seine, is the capital of the Haute-Normandie region and the historic capital city of Normandy. Once one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe , it was the seat of the Exchequer of Normandy in the Middle Ages...

. As tax collectors arrived at other French cities the revolt spread and violence broke out in Paris and most of France's other northern cities. The regency was forced to repeal the taxes to calm the situation.