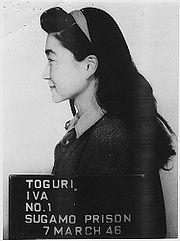

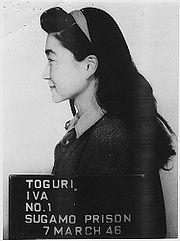

Iva Toguri D'Aquino

Encyclopedia

Iva Ikuko Toguri D'Aquino (July 4, 1916 – September 26, 2006), was an American citizen who participated in English-language propaganda broadcast transmitted by Radio Tokyo

to Allied

soldiers in the South Pacific

during World War II

. Although on the "Zero Hour" radio show, Toguri called herself "Orphan Ann," she quickly became identified with the moniker "Tokyo Rose

", a name that was coined by Allied soldiers and that predated her broadcasts. After the Japanese defeat, Toguri was detained for a year by the U.S. military before being released for lack of evidence. Department of Justice

officials agreed that her broadcasts were "innocuous". But when Toguri tried to return to the US, a popular uproar ensued, prompting the Federal Bureau of Investigation

to renew its investigation of Toguri's wartime activities. She was subsequently charged by the United States Attorney's Office

with eight counts of treason

. Her 1949 trial resulted in a conviction on one count, making her the seventh American to be convicted on that charge. In 1974, investigative journalists

found that key witnesses claimed they were forced to lie during testimony. Toguri was pardoned by U.S.

President

Gerald Ford

in 1977.

, a daughter of Japanese

immigrants. Her father, Jun Toguri, had come to the U.S. in 1899, and her mother, Fumi, in 1913. Iva was a Girl Scout as a child, and was raised as a Methodist. She attended grammar school

s in Mexico and San Diego before returning with her family to Los Angeles. There she finished grammar school, attended high school

, and graduated from the University of California, Los Angeles

, with a degree in zoology

. She then went to work in her parents' shop. As a registered Republican, she voted for Wendell Wilkie in the 1940 presidential election.

On July 5, 1941, Toguri sailed for Japan from Los Angeles' San Pedro

area, to visit an ailing relative and to possibly study medicine

. The U.S. State Department issued her a Certificate of Identification; she did not have a passport

. In September, Toguri applied to the U.S. Vice Consul in Japan for a passport, stating she wished to return to her home in the U.S. Her request was forwarded to the State Department, but the answer had not returned by the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor

(December 7, 1941) and she was stranded in Japan.

With the beginning of American involvement in the Pacific War

With the beginning of American involvement in the Pacific War

, Toguri, like a number of other Americans in Japanese territory, was pressured by the Japanese central government

under Hideki Tojo

to renounce her United States citizenship. She refused to do so. Toguri was subsequently declared an enemy alien and was refused a war ration card. "A tiger does not change its stripes" is a quote attributed to her. To support herself, she found work as a typist at a Japanese news agency

and eventually worked in a similar capacity for Radio Tokyo.

In November 1943, Allied prisoners of war

forced to broadcast propaganda

selected her to host portions of the one-hour radio show The Zero Hour. Her producer was an Australian Army

officer, Major Charles Cousens, who had pre-war broadcast experience and had been captured at the fall of Singapore

. Cousens had been tortured and coerced to work on radio broadcasts, as had his assistants, U.S. Army

Captain Wallace Ince and Philippine Army

Lieutenant Normando Ildefonso "Norman" Reyes. Toguri had previously risked her life smuggling food into the nearby prisoner of war (POW) camp where Cousens and Ince were held, gaining the inmates' trust. After she refused to broadcast anti-American propaganda, Toguri was assured by Major Cousens and Captain Ince that they would not write scripts having her say anything against the United States. True to their word, no such propaganda was found in her broadcasts. Toguri hosted a total of 340 broadcasts of The Zero Hour.

Under the stage name

s "Ann" (for "Announcer") and later "Orphan Annie" and possibly "Your Favorite Enemy, Annie", reportedly in reference to the comic strip

character Little Orphan Annie

, (or more likely, a reference to "Orphans", the nickname given to Australian troops separated from their divisions in battle), Toguri performed in comedy sketches and introduced recorded music, but never participated in any actual newscasts, with on-air speaking time of generally about 20 minutes. Though earning only 150 yen, or about $7, per month, she used some of her earnings to feed POWs, smuggling food in as she did before.

Toguri aimed most of her comments toward her fellow Americans ("my fellow orphans"), using American slang and playing American music. She routinely referred to American and allied troops in the Pacific theater as "boneheads". In one of the few surviving recordings of her show, she refers to herself as "your 'Number One' enemy."

At no time did Toguri call herself "Tokyo Rose

" during the war, and in fact there was no evidence that any other broadcaster had done so. The name was a catch-all used by Allied forces for all of the women who were heard on Japanese propaganda radio.

She married Felipe D'Aquino (last name sometimes given only as Aquino), a Portuguese

citizen of Japanese-Portuguese descent, on April 19, 1945. At the same time, Toguri formally became a Catholic, a faith she would keep through her prison years. The marriage was registered with the Portuguese Consulate in Tokyo, with Toguri declining to take her husband's citizenship.

After Japan's unconditional surrender

After Japan's unconditional surrender

(August 15, 1945), reporters Harry T. Brundidge of Cosmopolitan

Magazine and Clark Lee of Hearst's International News Service

(INS) offered $2,000 (the equivalent of a year's wages in Occupied Japan) for an exclusive interview with "Tokyo Rose".

In need of money, and still trying to get home, Iva stepped forward to claim the money, but instead found herself arrested, on September 5, 1945, in Yokohama

. Brundidge not only used her arrest and subsequent public press conference as an excuse to renege on the "exclusive interview" deal and nullify any payment, but also tried to sell his transcript of the interview as Iva's "confession". She was released after a year in jail when neither the FBI nor General Douglas MacArthur

's staff found any evidence she had aided the Japanese Axis forces. Furthermore, the American and Australia

n prisoners of war who wrote her scripts assured her (and the Allied headquarters) that she had committed no wrongdoing.

The case history at the FBI's website

states, "The FBI's investigation of Aquino's activities had covered a period of some five years. During the course of that investigation, the FBI had interviewed hundreds of former members of the U.S. Armed Forces who had served in the South Pacific during World War II, unearthed forgotten Japanese documents, and turned up recordings of Aquino's broadcasts". Investigating with the U.S. Army's Counterintelligence Corps, they "conducted an extensive investigation to determine whether Aquino had committed crimes against the U.S. By the following October, authorities decided that the evidence then known did not merit prosecution, and she was released."

Upon her request to return to the United States to have her child born on American soil, the influential gossip columnist

and radio host Walter Winchell

lobbied against her. Her baby was born in Japan, but died shortly after. Following her child's death, D'Aquino was rearrested by the U.S. military authorities and transported to San Francisco

, on September 25, 1948, where she was charged by federal prosecutors

with the crime of treason for "adhering to, and giving aid and comfort to, the Imperial Government of Japan during World War II".

Her trial

Her trial

on eight "overt acts" of treason began on July 5, 1949, at the Federal District Court in San Francisco. During what was at the time the costliest and longest trial in American history, totaling more than half a million dollars, the prosecution presented 46 witnesses, including two of Toguri's former supervisors at Radio Tokyo, and soldiers who testified they could not distinguish between what they had heard on radio broadcasts and what they had heard by way of rumor. Although boxes of tapes were brought by prosecutors to the courthouse and rested near the prosecution table, none were entered into evidence and played for the jury. Toguri claimed she and her associates subtly sabotaged the Japanese war effort.

Toguri was defended by a team of attorneys, led by Wayne Mortimer Collins

, a prominent Japanese-American rights advocate. Collins enlisted the help of Theodore Tamba, who became one of Toguri's closest friends, a relationship which continued until his death in the 1970s. Both Charles Cousens and Wallace Ince paid for their own airfare to attend the trial as witnesses and testify on Toguri's behalf.

During the trial, the former supervisor at Radio Tokyo testified that:

Another co-worker testified that Toguri said, "Now you fellows have lost all your ships. Now you really are orphans of the Pacific

. How do you think you will ever get home?"

On September 29, 1949, the jury found Toguri guilty on a sole count, Count VI, which stated, "That on a day during October, 1944, the exact date being to the Grand Jurors unknown, said defendant, at Tokyo, Japan, in a broadcasting studio of The Broadcasting Corporation of Japan, did speak into a microphone concerning the loss of ships." She was fined $10,000 and given a 10-year prison sentence, with Toguri's attorney Collins lambasting the verdict as "Guilty without evidence". She was sent to the Federal Reformatory for Women at Alderson, West Virginia

. She was parole

d after serving six years and two months, and released January 28, 1956. She moved to Chicago, Illinois

. The FBI's case history notes, "Neither Brundidge nor the [suborned] witness [Hiromu Yagi] testified at trial because of the taint of perjury. Nor was Brundidge prosecuted for subornation of perjury

."

, Iva moved to Chicago, where her father had opened the J. Toguri Mercantile Company Japanese-import retail store during the war, following the release of the Toguri family from internment at the Gila River War Relocation Center

in September 1943. She lived and worked at the store on Belmont Avenue in the Lakeview

neighborhood until her death in 2006, her former notoriety all but forgotten.

Following the trial, Iva's husband, who had been arrested and put on parole immediately upon his arrival in the U.S. to be a witness for the defense, was required by law to return to Japan. Operatives of the FBI and INS

boarded his ship as it was leaving Hawaii and coerced him into signing a document that barred him from returning to the U.S. He and Iva would never see one another again, as he was precluded from entering the country and she could never leave it for fear of not being allowed to return. Although they remained technically married but effectively separated by decree, until 1980, when Iva resumed her maiden name. Toguri never reunited with or again saw her husband and, after 30 years of forced separation, they divorced in 1980 so that he could get on with his life without her. He died in 1996, nearly half a century after the trial that separated them.

In 1976, an investigation by Chicago Tribune

In 1976, an investigation by Chicago Tribune

reporter Ron Yates discovered that Kenkichi Oki and George Mitsushio, who had given the most damaging testimony at Toguri's trial, had lied under oath. They stated they had been threatened by the FBI and U.S. occupation police and told what to say and what not to say just hours before the trial. This was followed up by a Morley Safer

report on the television news program 60 Minutes

.

Due to these revelations, U.S. President Gerald Ford

granted a full and unconditional pardon

to Iva Toguri D'Aquino on January 19, 1977, his last full day in office. The decision was supported by a unanimous vote in both houses of the California State Legislature

, the national Japanese American Citizens League

, and S. I. Hayakawa

, then a United States Senator from California

. The pardon restored her U.S. citizenship

, which had been abrogated as a result of her conviction.

Veterans Committee (sponsors of the Memorial Day

Parade in Washington D.C. and the National World War II Memorial

, the newest monument on the National Mall

), citing "her indomitable spirit, love of country, and the example of courage she has given her fellow Americans", awarded Toguri its annual Edward J. Herlihy Citizenship Award. According to one biographer, Toguri found it the most memorable day of her life.

On September 26, 2006, at the age of 90, Toguri died in a Chicago hospital of natural causes.

in her obituary noted, "The broadcasts did nothing to dim American morale. The servicemen enjoyed the recordings of American popular music, and the United States Navy bestowed a satirical citation on Tokyo Rose at war’s end for her entertainment value."

The first registered rock group using the name Tokyo Rose was formed in the summer of 1980. They are most known for their video which tells the story of the war time Tokyo Rose. Tokyo Rose

is also the name of an emo/pop band hailing from New Jersey. Tokyo Rose

is a 1989 album by Van Dyke Parks

. The album attempts to reflect an intersection between Japanese and American cultures, a common concern during the 1980s. The Canadian group Idle Eyes

had a hit in 1985 in Canada with the song "Tokyo Rose" from their self-titled debut from WEA Music Canada. Vigilantes of Love

scored a hit with "Tokyo Rose" from their 1997 album, Slow Dark Train.

Dated articles and reports

NHK

NHK is Japan's national public broadcasting organization. NHK, which has always identified itself to its audiences by the English pronunciation of its initials, is a publicly owned corporation funded by viewers' payments of a television license fee....

to Allied

Allies of World War II

The Allies of World War II were the countries that opposed the Axis powers during the Second World War . Former Axis states contributing to the Allied victory are not considered Allied states...

soldiers in the South Pacific

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.At 165.2 million square kilometres in area, this largest division of the World...

during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. Although on the "Zero Hour" radio show, Toguri called herself "Orphan Ann," she quickly became identified with the moniker "Tokyo Rose

Tokyo Rose

Tokyo Rose was a generic name given by Allied forces in the South Pacific during World War II to any of approximately a dozen English-speaking female broadcasters of Japanese propaganda. The intent of these broadcasts was to disrupt the morale of Allied forces listening to the broadcast...

", a name that was coined by Allied soldiers and that predated her broadcasts. After the Japanese defeat, Toguri was detained for a year by the U.S. military before being released for lack of evidence. Department of Justice

United States Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice , is the United States federal executive department responsible for the enforcement of the law and administration of justice, equivalent to the justice or interior ministries of other countries.The Department is led by the Attorney General, who is nominated...

officials agreed that her broadcasts were "innocuous". But when Toguri tried to return to the US, a popular uproar ensued, prompting the Federal Bureau of Investigation

Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation is an agency of the United States Department of Justice that serves as both a federal criminal investigative body and an internal intelligence agency . The FBI has investigative jurisdiction over violations of more than 200 categories of federal crime...

to renew its investigation of Toguri's wartime activities. She was subsequently charged by the United States Attorney's Office

United States Attorney

United States Attorneys represent the United States federal government in United States district court and United States court of appeals. There are 93 U.S. Attorneys stationed throughout the United States, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands...

with eight counts of treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

. Her 1949 trial resulted in a conviction on one count, making her the seventh American to be convicted on that charge. In 1974, investigative journalists

Investigative journalism

Investigative journalism is a form of journalism in which reporters deeply investigate a single topic of interest, often involving crime, political corruption, or corporate wrongdoing. An investigative journalist may spend months or years researching and preparing a report. Investigative journalism...

found that key witnesses claimed they were forced to lie during testimony. Toguri was pardoned by U.S.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Gerald Ford

Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph "Jerry" Ford, Jr. was the 38th President of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977, and the 40th Vice President of the United States serving from 1973 to 1974...

in 1977.

Early life

was born in Los AngelesLos Ángeles

Los Ángeles is the capital of the province of Biobío, in the commune of the same name, in Region VIII , in the center-south of Chile. It is located between the Laja and Biobío rivers. The population is 123,445 inhabitants...

, a daughter of Japanese

Japanese people

The are an ethnic group originating in the Japanese archipelago and are the predominant ethnic group of Japan. Worldwide, approximately 130 million people are of Japanese descent; of these, approximately 127 million are residents of Japan. People of Japanese ancestry who live in other countries...

immigrants. Her father, Jun Toguri, had come to the U.S. in 1899, and her mother, Fumi, in 1913. Iva was a Girl Scout as a child, and was raised as a Methodist. She attended grammar school

Grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and some other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching classical languages but more recently an academically-oriented secondary school.The original purpose of mediaeval...

s in Mexico and San Diego before returning with her family to Los Angeles. There she finished grammar school, attended high school

High school

High school is a term used in parts of the English speaking world to describe institutions which provide all or part of secondary education. The term is often incorporated into the name of such institutions....

, and graduated from the University of California, Los Angeles

University of California, Los Angeles

The University of California, Los Angeles is a public research university located in the Westwood neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, USA. It was founded in 1919 as the "Southern Branch" of the University of California and is the second oldest of the ten campuses...

, with a degree in zoology

Zoology

Zoology |zoölogy]]), is the branch of biology that relates to the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinct...

. She then went to work in her parents' shop. As a registered Republican, she voted for Wendell Wilkie in the 1940 presidential election.

On July 5, 1941, Toguri sailed for Japan from Los Angeles' San Pedro

San Pedro, Los Angeles, California

San Pedro is a port district of the city of Los Angeles, California, United States. It was annexed in 1909 and is a major seaport of the area...

area, to visit an ailing relative and to possibly study medicine

Medicine

Medicine is the science and art of healing. It encompasses a variety of health care practices evolved to maintain and restore health by the prevention and treatment of illness....

. The U.S. State Department issued her a Certificate of Identification; she did not have a passport

Passport

A passport is a document, issued by a national government, which certifies, for the purpose of international travel, the identity and nationality of its holder. The elements of identity are name, date of birth, sex, and place of birth....

. In September, Toguri applied to the U.S. Vice Consul in Japan for a passport, stating she wished to return to her home in the U.S. Her request was forwarded to the State Department, but the answer had not returned by the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor

Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike conducted by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on the morning of December 7, 1941...

(December 7, 1941) and she was stranded in Japan.

Zero Hour

Pacific War

The Pacific War, also sometimes called the Asia-Pacific War refers broadly to the parts of World War II that took place in the Pacific Ocean, its islands, and in East Asia, then called the Far East...

, Toguri, like a number of other Americans in Japanese territory, was pressured by the Japanese central government

Japanese central government (WWII)

In the administration of Japan dominated by the Toseiha movement during World War II, the civil central government of Japan was under the management of some military men, and of some civilians:-Supreme head of government:...

under Hideki Tojo

Hideki Tōjō

Hideki Tōjō was a general of the Imperial Japanese Army , the leader of the Taisei Yokusankai, and the 40th Prime Minister of Japan during most of World War II, from 17 October 1941 to 22 July 1944...

to renounce her United States citizenship. She refused to do so. Toguri was subsequently declared an enemy alien and was refused a war ration card. "A tiger does not change its stripes" is a quote attributed to her. To support herself, she found work as a typist at a Japanese news agency

News agency

A news agency is an organization of journalists established to supply news reports to news organizations: newspapers, magazines, and radio and television broadcasters. Such an agency may also be referred to as a wire service, newswire or news service.-History:The oldest news agency is Agence...

and eventually worked in a similar capacity for Radio Tokyo.

In November 1943, Allied prisoners of war

Prisoner of war

A prisoner of war or enemy prisoner of war is a person, whether civilian or combatant, who is held in custody by an enemy power during or immediately after an armed conflict...

forced to broadcast propaganda

Propaganda

Propaganda is a form of communication that is aimed at influencing the attitude of a community toward some cause or position so as to benefit oneself or one's group....

selected her to host portions of the one-hour radio show The Zero Hour. Her producer was an Australian Army

Australian Army

The Australian Army is Australia's military land force. It is part of the Australian Defence Force along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. While the Chief of Defence commands the Australian Defence Force , the Army is commanded by the Chief of Army...

officer, Major Charles Cousens, who had pre-war broadcast experience and had been captured at the fall of Singapore

Battle of Singapore

The Battle of Singapore was fought in the South-East Asian theatre of the Second World War when the Empire of Japan invaded the Allied stronghold of Singapore. Singapore was the major British military base in Southeast Asia and nicknamed the "Gibraltar of the East"...

. Cousens had been tortured and coerced to work on radio broadcasts, as had his assistants, U.S. Army

United States Army

The United States Army is the main branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is the largest and oldest established branch of the U.S. military, and is one of seven U.S. uniformed services...

Captain Wallace Ince and Philippine Army

Philippine Army

The Philippine Army is the ground arm of the Armed Forces of the Philippines . Its official name in Tagalog is Hukbong Katihan ng Pilipinas. On July 23, 2010, President Benigno Aquino III appointed Maj. Gen...

Lieutenant Normando Ildefonso "Norman" Reyes. Toguri had previously risked her life smuggling food into the nearby prisoner of war (POW) camp where Cousens and Ince were held, gaining the inmates' trust. After she refused to broadcast anti-American propaganda, Toguri was assured by Major Cousens and Captain Ince that they would not write scripts having her say anything against the United States. True to their word, no such propaganda was found in her broadcasts. Toguri hosted a total of 340 broadcasts of The Zero Hour.

Under the stage name

Stage name

A stage name, also called a showbiz name or screen name, is a pseudonym used by performers and entertainers such as actors, wrestlers, comedians, and musicians.-Motivation to use a stage name:...

s "Ann" (for "Announcer") and later "Orphan Annie" and possibly "Your Favorite Enemy, Annie", reportedly in reference to the comic strip

Comic strip

A comic strip is a sequence of drawings arranged in interrelated panels to display brief humor or form a narrative, often serialized, with text in balloons and captions....

character Little Orphan Annie

Little Orphan Annie

Little Orphan Annie was a daily American comic strip created by Harold Gray and syndicated by Tribune Media Services. The strip took its name from the 1885 poem "Little Orphant Annie" by James Whitcomb Riley, and made its debut on August 5, 1924 in the New York Daily News...

, (or more likely, a reference to "Orphans", the nickname given to Australian troops separated from their divisions in battle), Toguri performed in comedy sketches and introduced recorded music, but never participated in any actual newscasts, with on-air speaking time of generally about 20 minutes. Though earning only 150 yen, or about $7, per month, she used some of her earnings to feed POWs, smuggling food in as she did before.

Toguri aimed most of her comments toward her fellow Americans ("my fellow orphans"), using American slang and playing American music. She routinely referred to American and allied troops in the Pacific theater as "boneheads". In one of the few surviving recordings of her show, she refers to herself as "your 'Number One' enemy."

At no time did Toguri call herself "Tokyo Rose

Tokyo Rose

Tokyo Rose was a generic name given by Allied forces in the South Pacific during World War II to any of approximately a dozen English-speaking female broadcasters of Japanese propaganda. The intent of these broadcasts was to disrupt the morale of Allied forces listening to the broadcast...

" during the war, and in fact there was no evidence that any other broadcaster had done so. The name was a catch-all used by Allied forces for all of the women who were heard on Japanese propaganda radio.

She married Felipe D'Aquino (last name sometimes given only as Aquino), a Portuguese

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

citizen of Japanese-Portuguese descent, on April 19, 1945. At the same time, Toguri formally became a Catholic, a faith she would keep through her prison years. The marriage was registered with the Portuguese Consulate in Tokyo, with Toguri declining to take her husband's citizenship.

Arrest

Victory over Japan Day

Victory over Japan Day is a name chosen for the day on which the Surrender of Japan occurred, effectively ending World War II, and subsequent anniversaries of that event...

(August 15, 1945), reporters Harry T. Brundidge of Cosmopolitan

Cosmopolitan (magazine)

Cosmopolitan is an international magazine for women. It was first published in 1886 in the United States as a family magazine, was later transformed into a literary magazine and eventually became a women's magazine in the late 1960s...

Magazine and Clark Lee of Hearst's International News Service

International News Service

International News Service was a U.S.-based news agency founded by newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst in 1909.Established two years after the Scripps family founded the United Press Association, INS scrapped among the newswires...

(INS) offered $2,000 (the equivalent of a year's wages in Occupied Japan) for an exclusive interview with "Tokyo Rose".

In need of money, and still trying to get home, Iva stepped forward to claim the money, but instead found herself arrested, on September 5, 1945, in Yokohama

Yokohama

is the capital city of Kanagawa Prefecture and the second largest city in Japan by population after Tokyo and most populous municipality of Japan. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of Tokyo, in the Kantō region of the main island of Honshu...

. Brundidge not only used her arrest and subsequent public press conference as an excuse to renege on the "exclusive interview" deal and nullify any payment, but also tried to sell his transcript of the interview as Iva's "confession". She was released after a year in jail when neither the FBI nor General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur was an American general and field marshal of the Philippine Army. He was a Chief of Staff of the United States Army during the 1930s and played a prominent role in the Pacific theater during World War II. He received the Medal of Honor for his service in the...

's staff found any evidence she had aided the Japanese Axis forces. Furthermore, the American and Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

n prisoners of war who wrote her scripts assured her (and the Allied headquarters) that she had committed no wrongdoing.

The case history at the FBI's website

Website

A website, also written as Web site, web site, or simply site, is a collection of related web pages containing images, videos or other digital assets. A website is hosted on at least one web server, accessible via a network such as the Internet or a private local area network through an Internet...

states, "The FBI's investigation of Aquino's activities had covered a period of some five years. During the course of that investigation, the FBI had interviewed hundreds of former members of the U.S. Armed Forces who had served in the South Pacific during World War II, unearthed forgotten Japanese documents, and turned up recordings of Aquino's broadcasts". Investigating with the U.S. Army's Counterintelligence Corps, they "conducted an extensive investigation to determine whether Aquino had committed crimes against the U.S. By the following October, authorities decided that the evidence then known did not merit prosecution, and she was released."

Upon her request to return to the United States to have her child born on American soil, the influential gossip columnist

Gossip columnist

A gossip columnist is someone who writes a gossip column in a newspaper or magazine, especially a gossip magazine. Gossip columns are material written in a light, informal style, which relates the gossip columnist's opinions about the personal lives or conduct of celebrities from show business ,...

and radio host Walter Winchell

Walter Winchell

Walter Winchell was an American newspaper and radio gossip commentator.-Professional career:Born Walter Weinschel in New York City, he left school in the sixth grade and started performing in a vaudeville troupe known as Gus Edwards' "Newsboys Sextet."His career in journalism was begun by posting...

lobbied against her. Her baby was born in Japan, but died shortly after. Following her child's death, D'Aquino was rearrested by the U.S. military authorities and transported to San Francisco

San Francisco, California

San Francisco , officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the financial, cultural, and transportation center of the San Francisco Bay Area, a region of 7.15 million people which includes San Jose and Oakland...

, on September 25, 1948, where she was charged by federal prosecutors

United States Attorney

United States Attorneys represent the United States federal government in United States district court and United States court of appeals. There are 93 U.S. Attorneys stationed throughout the United States, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands...

with the crime of treason for "adhering to, and giving aid and comfort to, the Imperial Government of Japan during World War II".

Treason trial

Trial (law)

In law, a trial is when parties to a dispute come together to present information in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court...

on eight "overt acts" of treason began on July 5, 1949, at the Federal District Court in San Francisco. During what was at the time the costliest and longest trial in American history, totaling more than half a million dollars, the prosecution presented 46 witnesses, including two of Toguri's former supervisors at Radio Tokyo, and soldiers who testified they could not distinguish between what they had heard on radio broadcasts and what they had heard by way of rumor. Although boxes of tapes were brought by prosecutors to the courthouse and rested near the prosecution table, none were entered into evidence and played for the jury. Toguri claimed she and her associates subtly sabotaged the Japanese war effort.

Toguri was defended by a team of attorneys, led by Wayne Mortimer Collins

Wayne M. Collins

Wayne M. Collins was a civil rights attorney who worked on cases related to the Japanese American evacuation and internment.-Biography:Collins was born in Sacramento, California and was raised and educated in San Francisco....

, a prominent Japanese-American rights advocate. Collins enlisted the help of Theodore Tamba, who became one of Toguri's closest friends, a relationship which continued until his death in the 1970s. Both Charles Cousens and Wallace Ince paid for their own airfare to attend the trial as witnesses and testify on Toguri's behalf.

During the trial, the former supervisor at Radio Tokyo testified that:

Another co-worker testified that Toguri said, "Now you fellows have lost all your ships. Now you really are orphans of the Pacific

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.At 165.2 million square kilometres in area, this largest division of the World...

. How do you think you will ever get home?"

On September 29, 1949, the jury found Toguri guilty on a sole count, Count VI, which stated, "That on a day during October, 1944, the exact date being to the Grand Jurors unknown, said defendant, at Tokyo, Japan, in a broadcasting studio of The Broadcasting Corporation of Japan, did speak into a microphone concerning the loss of ships." She was fined $10,000 and given a 10-year prison sentence, with Toguri's attorney Collins lambasting the verdict as "Guilty without evidence". She was sent to the Federal Reformatory for Women at Alderson, West Virginia

Alderson, West Virginia

Alderson, a town in the US State of West Virginia, is split geographically by the Greenbrier River, with portions in both Greenbrier and Monroe Counties. Although split physically by the river, the town functions as one entity, including that of town government...

. She was parole

Parole

Parole may have different meanings depending on the field and judiciary system. All of the meanings originated from the French parole . Following its use in late-resurrected Anglo-French chivalric practice, the term became associated with the release of prisoners based on prisoners giving their...

d after serving six years and two months, and released January 28, 1956. She moved to Chicago, Illinois

Chicago

Chicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

. The FBI's case history notes, "Neither Brundidge nor the [suborned] witness [Hiromu Yagi] testified at trial because of the taint of perjury. Nor was Brundidge prosecuted for subornation of perjury

Subornation of perjury

The legal term subornation of perjury describes the crime of persuading a person to commit perjury; and also describes the circumstance wherein an attorney causes or allows another party to lie...

."

Post-prison life

After her parole, resisting efforts at deportationDeportation

Deportation means the expulsion of a person or group of people from a place or country. Today it often refers to the expulsion of foreign nationals whereas the expulsion of nationals is called banishment, exile, or penal transportation...

, Iva moved to Chicago, where her father had opened the J. Toguri Mercantile Company Japanese-import retail store during the war, following the release of the Toguri family from internment at the Gila River War Relocation Center

Gila River War Relocation Center

The Gila River War Relocation Center was an internment camp built by the War Relocation Authority for internment of Japanese Americans during the Second World War. It was located about southeast of Phoenix, Arizona....

in September 1943. She lived and worked at the store on Belmont Avenue in the Lakeview

Lakeview, Chicago

Lake View, or Lakeview, is one of the 77 community area of the Chicago, Illinois, located in the city's North Side. It is bordered by West Diversey Parkway on the south, West Irving Park Road on the north, North Ravenswood Avenue on the west, and the shore of Lake Michigan on the east...

neighborhood until her death in 2006, her former notoriety all but forgotten.

Following the trial, Iva's husband, who had been arrested and put on parole immediately upon his arrival in the U.S. to be a witness for the defense, was required by law to return to Japan. Operatives of the FBI and INS

Immigration and Naturalization Service

The United States Immigration and Naturalization Service , now referred to as Legacy INS, ceased to exist under that name on March 1, 2003, when most of its functions were transferred from the Department of Justice to three new components within the newly created Department of Homeland Security, as...

boarded his ship as it was leaving Hawaii and coerced him into signing a document that barred him from returning to the U.S. He and Iva would never see one another again, as he was precluded from entering the country and she could never leave it for fear of not being allowed to return. Although they remained technically married but effectively separated by decree, until 1980, when Iva resumed her maiden name. Toguri never reunited with or again saw her husband and, after 30 years of forced separation, they divorced in 1980 so that he could get on with his life without her. He died in 1996, nearly half a century after the trial that separated them.

Presidential pardon

Chicago Tribune

The Chicago Tribune is a major daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, and the flagship publication of the Tribune Company. Formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" , it remains the most read daily newspaper of the Chicago metropolitan area and the Great Lakes region and is...

reporter Ron Yates discovered that Kenkichi Oki and George Mitsushio, who had given the most damaging testimony at Toguri's trial, had lied under oath. They stated they had been threatened by the FBI and U.S. occupation police and told what to say and what not to say just hours before the trial. This was followed up by a Morley Safer

Morley Safer

Morley Safer is a Canadian reporter and correspondent for CBS News. He is best known for his long tenure on the newsmagazine 60 Minutes, which began in December 1970.-Life and career:...

report on the television news program 60 Minutes

60 Minutes

60 Minutes is an American television news magazine, which has run on CBS since 1968. The program was created by producer Don Hewitt who set it apart by using a unique style of reporter-centered investigation....

.

Due to these revelations, U.S. President Gerald Ford

Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph "Jerry" Ford, Jr. was the 38th President of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977, and the 40th Vice President of the United States serving from 1973 to 1974...

granted a full and unconditional pardon

Pardon

Clemency means the forgiveness of a crime or the cancellation of the penalty associated with it. It is a general concept that encompasses several related procedures: pardoning, commutation, remission and reprieves...

to Iva Toguri D'Aquino on January 19, 1977, his last full day in office. The decision was supported by a unanimous vote in both houses of the California State Legislature

California State Legislature

The California State Legislature is the state legislature of the U.S. state of California. It is a bicameral body consisting of the lower house, the California State Assembly, with 80 members, and the upper house, the California State Senate, with 40 members...

, the national Japanese American Citizens League

Japanese American Citizens League

The was formed in 1929 to protect the rights of Japanese Americans from the state and federal governments. It fought for civil rights for Japanese Americans, assisted those in internment camps during World War II, and led a successful campaign for redress for internment from the U.S...

, and S. I. Hayakawa

S. I. Hayakawa

Samuel Ichiye Hayakawa was a Canadian-born American academic and political figure of Japanese ancestry. He was an English professor, and served as president of San Francisco State University and then as United States Senator from California from 1977 to 1983...

, then a United States Senator from California

California

California is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area...

. The pardon restored her U.S. citizenship

Citizenship

Citizenship is the state of being a citizen of a particular social, political, national, or human resource community. Citizenship status, under social contract theory, carries with it both rights and responsibilities...

, which had been abrogated as a result of her conviction.

Later life

On 15 January 2006, the World War IIWorld War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

Veterans Committee (sponsors of the Memorial Day

Memorial Day

Memorial Day is a United States federal holiday observed on the last Monday of May. Formerly known as Decoration Day, it originated after the American Civil War to commemorate the fallen Union soldiers of the Civil War...

Parade in Washington D.C. and the National World War II Memorial

National World War II Memorial

The U.S. National World War II Memorial is a National Memorial dedicated to Americans who served in the armed forces and as civilians during World War II...

, the newest monument on the National Mall

National Mall

The National Mall is an open-area national park in downtown Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States. The National Mall is a unit of the National Park Service , and is administered by the National Mall and Memorial Parks unit...

), citing "her indomitable spirit, love of country, and the example of courage she has given her fellow Americans", awarded Toguri its annual Edward J. Herlihy Citizenship Award. According to one biographer, Toguri found it the most memorable day of her life.

On September 26, 2006, at the age of 90, Toguri died in a Chicago hospital of natural causes.

Legacy

The FBI case history cited under References states, "As far as its propaganda value, Army analysis suggested that the program had no negative effect on troop morale and that it might even have raised it a bit". The New York TimesThe New York Times

The New York Times is an American daily newspaper founded and continuously published in New York City since 1851. The New York Times has won 106 Pulitzer Prizes, the most of any news organization...

in her obituary noted, "The broadcasts did nothing to dim American morale. The servicemen enjoyed the recordings of American popular music, and the United States Navy bestowed a satirical citation on Tokyo Rose at war’s end for her entertainment value."

Media depictions

Iva Toguri has been the subject of two movies and five documentaries:- 1946: Tokyo Rose, film; directed by Lew Landers. Lotus LongLotus LongBorn Lotus Pearl Shibata in New Jersey, Lotus Long was an American actor born to a father of Japanese ancestry and a mother of Hawai'ian ancestry. She came to Southern California during the 1920s to act in Hollywood films, and usually portrayed ethnic Asian female characters in supporting roles. ...

played a heavily fictionalized "Tokyo Rose", described on the film's posters as a "seductive jap traitress"; Byron BarrByron BarrByron Barr sometimes billed as Byron S. Barr, was an American actor born in Corning, Iowa.Barr was in 17 films in his career. He is perhaps best known for his role as Nino Zachetti in Double Indemnity, his first appearance...

played the G.I. protagonist, who kidnaps the Japanese announcer. Blake EdwardsBlake EdwardsBlake Edwards was an American film director, screenwriter and producer.Edwards' career began in the 1940s as an actor, but he soon turned to writing radio scripts at Columbia Pictures...

appeared in a supporting part. The film espoused the general public's view of "Tokyo Rose" at the time of Toguri's arrest. While the film's character was not referred to by her actual name, actress Lotus LongLotus LongBorn Lotus Pearl Shibata in New Jersey, Lotus Long was an American actor born to a father of Japanese ancestry and a mother of Hawai'ian ancestry. She came to Southern California during the 1920s to act in Hollywood films, and usually portrayed ethnic Asian female characters in supporting roles. ...

was made to look like Toguri. - 1969: The Story of "Tokyo Rose", CBS-TV and WGN radio documentary written and produced by Bill KurtisBill KurtisBill Kurtis is an American television journalist, producer, narrator, and news anchor. He is also the current host of A&E crime and news documentary shows, including Investigative Reports, American Justice, and Cold Case Files...

. - 1976: Tokyo Rose, CBS-TV documentary segment on 60 Minutes60 Minutes60 Minutes is an American television news magazine, which has run on CBS since 1968. The program was created by producer Don Hewitt who set it apart by using a unique style of reporter-centered investigation....

by Morley SaferMorley SaferMorley Safer is a Canadian reporter and correspondent for CBS News. He is best known for his long tenure on the newsmagazine 60 Minutes, which began in December 1970.-Life and career:...

, produced by Imrel Harvath. - 1995: U.S.A. vs. "Tokyo Rose", self-produced documentary by Antonio A. Montanari Jr., distributed by Cinema Guild.

- 1995: Tokyo Rose: Victim of Propaganda, A&E Biography documentary, hosted by Peter GravesPeter Graves (actor)Peter Aurness , known professionally as Peter Graves, was an American film and television actor. He was best known for his starring role in the CBS television series Mission: Impossible from 1967 to 1973...

, available on VHS (AAE-14023). - 1999: Tokyo Rose: Victim of Propaganda, History International, Produced by Scott Paddor, Editor Steve Pomerantz, A&E Director Bill Harris

- In 2004, actor George TakeiGeorge TakeiGeorge Hosato Takei Altman is an American actor, author, social activist and former civil politician. He is best known for his role in the television series Star Trek and its film spinoffs, in which he played Hikaru Sulu, helmsman of the...

announced he was working on a film titled Tokyo Rose, American Patriot, about Toguri's activities during the war. - 2008-9: Tokyo Rose, film; in development with Darkwoods Productions, the only entity granted life story rights by Iva Toguri, Frank DarabontFrank DarabontFrank Darabont is a Hungarian-American film director, screenwriter and producer who has been nominated for three Academy Awards and a Golden Globe. He has directed the films The Shawshank Redemption, The Green Mile, and The Mist, all based on stories by Stephen King...

to direct. Christopher HamptonChristopher HamptonChristopher James Hampton CBE, FRSL is a British playwright, screen writer and film director. He is best known for his play based on the novel Les Liaisons dangereuses and the film version Dangerous Liaisons and also more recently for writing the nominated screenplay for the film adaptation of...

, is the screenwriter for Tokyo Rose. - On 20 July 2009, History DetectivesHistory DetectivesHistory Detectives is a documentary television series on PBS. A group of researchers help people to seek answers to various historical questions they have, usually centering around a family heirloom, an old house or other historic object or structure...

(Season 7, Episode 705) aired a 20-minute segment entitled Tokyo Rose Recording researched by Gwendolyn WrightGwendolyn WrightGwendolyn Wright is an award-winning architectural historian, author, and co-host of the PBS television series "History Detectives". She is a professor of architecture at Columbia University, also holding appointments in both its departments of history and art history. Besides "History...

tracing the recording of live coverage of Iva Toguri's 25 September 1948 arrival in San Francisco under military escort for trial. The investigation of the origins of this recording documents the involvement of the self-serving reporter Harry T. Brundidge and his part in the fraudalent case against her.

The first registered rock group using the name Tokyo Rose was formed in the summer of 1980. They are most known for their video which tells the story of the war time Tokyo Rose. Tokyo Rose

Tokyo Rose (band)

Tokyo Rose is an indie rock band from New Brunswick, New Jersey. As of 2007 they have released 3 studio albums, and a short demo EP, whilst extensively changing their lineup over their 7 years of activity.-History:...

is also the name of an emo/pop band hailing from New Jersey. Tokyo Rose

Tokyo Rose (album)

Tokyo Rose is a 1989 album by American musician Van Dyke Parks. The album concerns the intersection between Japanese and American cultures, particularly as reflected in the competitive "Trade War" of the 1980s...

is a 1989 album by Van Dyke Parks

Van Dyke Parks

Van Dyke Parks is an American composer, arranger, producer, musician, singer, author and actor. Parks is perhaps best known for his contributions as a lyricist on the Beach Boys album Smile....

. The album attempts to reflect an intersection between Japanese and American cultures, a common concern during the 1980s. The Canadian group Idle Eyes

Idle Eyes

Idle Eyes is a Canadian band formed in the 1980s by Tad Campbell, Donna McConville, and others. They are best known for their #1 1985 Canadian single "Tokyo Rose"...

had a hit in 1985 in Canada with the song "Tokyo Rose" from their self-titled debut from WEA Music Canada. Vigilantes of Love

Vigilantes of Love

Vigilantes of Love is a rock band fronted by Bill Mallonee with a large number of secondary players drawn from the musician pool in and around Athens, Georgia...

scored a hit with "Tokyo Rose" from their 1997 album, Slow Dark Train.

See also

- Axis Sally (disambiguation)

- Harold HarbyHarold HarbyNot to be confused with Harold A. Henry, Los Angeles City Council member 1945–66.Harold Harby was elected to the Los Angeles, California, City Council in 1939, but he had to leave office in 1942 when he was convicted of using a city car for a trip out of the state. He was reelected in 1943 and...

, Los Angeles City Council member, 1939–42, 1943–57, urged the council to keep Tokyo Rose out of America - Philippe HenriotPhilippe HenriotPhilippe Henriot was a French politician.Moving to the far right after beginnings in Roman Catholic conservatism in the Republican Federation, Henriot was elected to the Third Republic's Chamber of Deputies for the Gironde département in 1932 and 1936...

- Lord Haw Haw

- List of people pardoned or granted clemency by a United States president

- Ezra PoundEzra PoundEzra Weston Loomis Pound was an American expatriate poet and critic and a major figure in the early modernist movement in poetry...

- Stuttgart traitor

- Tokyo RoseTokyo RoseTokyo Rose was a generic name given by Allied forces in the South Pacific during World War II to any of approximately a dozen English-speaking female broadcasters of Japanese propaganda. The intent of these broadcasts was to disrupt the morale of Allied forces listening to the broadcast...

- P. G. WodehouseP. G. WodehouseSir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse, KBE was an English humorist, whose body of work includes novels, short stories, plays, poems, song lyrics, and numerous pieces of journalism. He enjoyed enormous popular success during a career that lasted more than seventy years and his many writings continue to be...

- English writer used in German radio broadcasts during World War II

External links

- "Orphan Ann" Home Page

- EarthStation1: Orphan Ann Broadcast Audio

- Mug shots of D'Aquino, thesmokinggun.com

- The Legend of Tokyo Rose book chapter by Ann Ellizabeth Pfau

Dated articles and reports

- Ex-'Tokyo Rose' suspect dies in Chicago, Associated PressAssociated PressThe Associated Press is an American news agency. The AP is a cooperative owned by its contributing newspapers, radio and television stations in the United States, which both contribute stories to the AP and use material written by its staff journalists...

via Times-Leader, 27 September 2006 - Richard Goldstein, D’Aquino, Linked to Tokyo Rose Broadcasts, Dies, New York Times, 27 September 2006

- Remembrances: Iva Toguri D'Aquino Dies at 90, All Things ConsideredAll Things ConsideredAll Things Considered is the flagship news program on the American network National Public Radio. It was the first news program on NPR, and is broadcast live worldwide through several outlets...

on National Public Radio, 27 September 2006 - Woman tried as ‘Tokyo Rose’ dies in Chicago, MSNBCMSNBCMSNBC is a cable news channel based in the United States available in the US, Germany , South Africa, the Middle East and Canada...

, 27 September 2006 - Obituary: Iva Toguri, Daily Telegraph (London), 28 September 2006