.gif)

John Jacobs (student leader)

Encyclopedia

John Gregory Jacobs was an American

student

and anti-war

activist in the 1960s and early 1970s. He was a leader in both Students for a Democratic Society

and the Weatherman

group, and an advocate of the use of violent force to overthrow the government of the United States. A fugitive since 1970, he died of melanoma in 1997.

journalist

who had been one of the first Americans to report on the Spanish Civil War

. His parents later moved to Connecticut

, where his father owned a bookstore. His childhood appeared to have been happy, and he was close to his parents.

In high school, Jacobs began to read Marxist

philosophy heavily, and was deeply interested in the Russian Revolution of 1917. He also admired Che Guevara

.

Jacobs graduated from high school in 1965 and enrolled at Columbia College of Columbia University

. During the summer between high school and college, he lived in New York City

and worked for a left-wing newspaper. Politically active in leftist political circles, Jacobs became acquainted with a large number of progressive intellectuals who further stimulated growth in his political ideology. For a brief time, he belonged to the Progressive Labor Party (PL), at the time a Maoist

communist party

. His first semester at Columbia, Jacobs met fellow freshman Mark Rudd

, and the two became friends.

(a social democratic

organization co-founded by Jack London

, Norman Thomas

, Upton Sinclair

and others). The chapter had sputtered for years, but became active in 1965 when it became known as SDS). Jacobs became very active in the group. A series of protests against on-campus military, CIA

and corporate

recruitment and ROTC

induction ceremonies rocked Columbia's campus for the next two years. Jacobs organized a protest in February 1967 against CIA recruiting at Columbia. Initially, the SDS chapter disavowed the action. But when Jacobs' sit-in proved popular among Columbia students, SDS claimed J.J. as one of their own. The CIA protest led to Jacobs' rapid rise within the chapter. The protests led Columbia President Grayson L. Kirk

to ban indoor protests at Columbia beginning in September 1967.

In March 1967, SDS member Bob Feldman accidentally discovered documents in a campus library detailing Columbia's affiliation with the Institute for Defense Analyses

(IDA), a weapons research think-tank affiliated with the Department of Defense

. Jacobs participated in the protests against the IDA, and was put on academic probation

for violating President Kirk's ban on indoor protests. Despite its growing influence on campus, the SDS chapter was deeply divided. One group of SDSers, called the "Praxis Axis," advocated more organizing and nonviolence. A second group, the "Action Faction," called for more aggressive action. In the early spring 1968, the Action Faction took control of Columbia University's SDS chapter. Jacobs was an active member of the Action Faction, and soon became one of its leaders. When Martin Luther King, Jr.

was assassinated on April 4, 1968, riots broke out in many American cities. Jacobs wandered the streets of Harlem

alone for most of the night, thrilled by the violence and inability of the police to maintain order. He adopted Georges Danton's

dictum of "Audacity, audacity, and more audacity!" as his own motto.

came just days after King's death. Columbia University officials were planning to build a new gymnasium on the south side of the campus. The building, which would have straddled a hill, would have two entrances—one on the north, upper side for students and one on the south, lower side for residents of Morningside Heights

, a mostly African American

neighborhood. To many students and local residents, it seemed as if Columbia were permitting blacks to use the gym, but only if they entered through the back door. On April 23, 1968, Rudd, Jacobs, and other members of Columbia's SDS chapter led a group of about 500 people in a protest against the gymnasium at the university Sundial. Part of the crowd attempted to take over Low Memorial Library

, but were repulsed by a counter-demonstration of conservative students. Some students tore down the fence surrounding the construction site, and were arrested by New York City police. Rudd then shouted that the crowd should seize Hamilton Hall

. The mob took over the building, taking a dean hostage. A number of militant young African Americans from Harlem

(rumored to be carrying guns) entered the building throughout the night and ordered the white students out. The Caucasian students seized Low Memorial Library. Over the next week, more than 1,000 Columbia students joined the protest and seized three more buildings. Jacobs led the seizure of Mathematics Hall. Among the protesters was Tom Hayden

, who arrived from Newark, New Jersey

, where he had been organizing poor inner-city residents. Rudd, Jacobs, Hayden and others organized communes inside the buildings, and educated the students in the theories of Marxism, racism

, and imperialism

. Columbia University refused to grant the protesters' demands regarding the gymnasium or amnesty for those who had seized the buildings. When the police were sent in to clear the buildings after a week, they brutally beat and clubbed hundreds of students. Jacobs suggested putting Columbia's rare Ming Dynasty vases in the windows to prevent sniper attacks, and pushing police out of windows. Black students in Hamilton Hall had contacted civil rights lawyers, who had arranged to be on-site during the arrests and for the students to leave Hamilton Hall peacefully. Angered by the lack of police violence, Jacobs set fire to a professor's office in Hamilton, an incident later blamed on the police. Thousands of students went on strike the next week, refusing to attend classes, and the university canceled final exams. The events catapulted Rudd into national prominence, and Rudd and Jacobs became national leaders in SDS. Jacobs began using the phrase "bring the war home," and it was widely adopted within the anti-war movement.

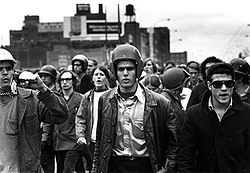

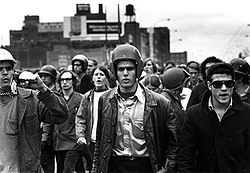

As college students across America began demanding "two, three, many Columbias," Jacobs became a recognized national leader of SDS and looked to by those who saw violence as the only way to respond to the governing political and economic system of the day. Jacobs began to look the part of a counterculture leader as well. In the middle of 1968, he began wearing tight jeans, a leather jacket, and a gold chain with a lion's tooth, and slicked his hair back 1950s-style to purposefully distinguish himself from the clean-cut, middle-class students who attended most anti-war protests. He became one of SDS' earliest and most prominent ideological thinkers, and was widely recognized as a charismatic persuasive speaker.

At the SDS national convention in East Lansing, Michigan

, in June 1968, Jacobs' thinking began to become even more radical. The East Lansing convention is best known for the interminable debates and ferocious parliamentary battles between the SDS National Office leadership (led by Michael Klonsky

and Bernardine Dohrn

) and the delegates from PL-controlled SDS chapters around the country.

Robin Palmer, an ex-Yippie

had drifted into SDS. Palmer argued, contrary to current SDS thinking, that President

Richard Nixon's

"silent majority" did exist. Most Americans, Palmer said, would not oppose imperialism

, militarism

and capitalism

if they were only shown the truth. Rather, most Americans knew the truth, and supported these ideologies actively and whole-heartedly. One of the Old Left's slogans had been "Serve the People." Convinced Palmer was correct, Jacobs proposed at the June 1968 convention that SDS adopt the slogan "Serve the People Shit" to reflect the public's support for greed and war.

in Chicago

, Illinois

. The group felt that mass demonstrations and electoral politics were not effective as a means of influencing national policy. But when the demonstrations proved popular and provoked a heavy-handed police response (as SDS predicted), the organization moved quickly to take credit for the protests.

But SDS itself was suffering from extreme factionalism. Since 1963, the Progressive Labor Party (PL) had been infiltrating its members into SDS in the hopes of convincing SDSers to join the party. Although only a tiny minority of SDS membership nationwide, PL supporters (with the support of the national party) often constituted a quarter or more of the delegates to national SDS conventions. Strongly disciplined and skilled at 'entryism

' and using parliamentary procedure, the PL supporters sought to seize control of SDS and turn the organization to the party's goals.

SDS leadership subsequently adopted a new policy in 1968 aimed at ending the factionalism. As the SDS National Council meeting convened in December 1968, National Secretary Mike Klonsky

published an article in the New Left Notes (SDS' newsletter) titled "Toward A Revolutionary Youth Movement

." A central document in SDS' final year, Klonsky's article advocated that SDS openly align itself with the working class and begin engaging in direct action

. The goal of SDS should be to build class consciousness

among students by organizing working people and moving off campus, and by attacking racism

, militarism

and the reactionary use of state police power. The "Revolutionary Youth Movement" (RYM) proposal was aimed squarely at PL, staking out some of the party's positions as the leadership's own while denouncing PL as deviant on others. The policy provoked five days of fierce debate, even shouting matches, between SDS' national leadership and supporters of PL. But on December 31, 1968, it passed and became national SDS policy.

Jacobs, however, felt that the RYM was insufficient. Within weeks of its adoption, he was hard at work on a new document which pushed the theoretical envelope even further. Jacobs was joined by several other SDS leaders, including Rudd, Dohrn, Jeff Jones

, Bill Ayers

, Terry Robbins

and five others. Throughout April and May, Jacobs and the others worked on the document. They met with RYM supporters in the Northeast and Midwest, as well as with more mainstream SDSers.

When the SDS National Convention opened in Chicago on June 18, 1969, Jacobs' manifesto, "You Don't Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows," was published in the SDS newspaper, New Left Notes. Although the other 10 SDS leaders had contributed to the document, Jacobs was the primary author of what came to be called the "Weatherman manifesto." Robbins suggested the title, lifted from a line in the Bob Dylan

song "Subterranean Homesick Blues

." Jacobs and 15 others signed it.

The "Weatherman" statement denounced imperialism and racism, and repudiated PL's claim that youth culture was bourgeois. The Weatherman manifesto also called for revolutionary violence at home to stop imperialism, and the formation of collectives in major cities to support the military struggle and stop factionalism. The Weatherman faction counted on RYM supporters to help them not only control the convention but also to pass the Weatherman manifesto. But Klonsky, Bob Avakian

, and Les Coleman—all key members of the pro-RYM caucus—disagreed with many of the positions advocated in the Weatherman statement. They issued their own position paper, "Revolutionary Youth Movement II" (RYM II). Although the Weatherman and RYM II factions were opposed to PL and nearly constituted a majority of delegates, they still lost control of the convention. Leaders of the Black Panther Party

made an appearance designed to attack PL supporters on the issue of racism. But when the Panthers made references to "pussy power," they and the SDS leadership were accused of male chauvinism. The next day, the Panthers accused PL of deviating from "true" Marxism-Leninism. PL leaders accused the Panthers and SDS leadership of redbaiting. Dohrn, Rudd, Jacobs, Klonsky and Robbins huddled in an attempt to strategize a way to defeat the PL faction. Dohrn took to the podium and demanded that all "true" SDSers follow her out of the convention hall. Gathering in an adjoining hall, Dohrn demanded that SDS expel all PL supporters. On June 20, the Weatherman and RYM II caucuses re-entered the main convention hall, accused the PL supporters of racism and being insufficiently opposed to imperialism, and demanded that all PL supporters be ejected. When they were not, Dohrn, Rudd, Jacobs and the other national leaders led approximately two-thirds of the delegates out of the convention hall.

After the split in SDS, The Weatherman/RYM II faction began establishing collectives in cities around the country. Jacobs moved to Chicago. There, he shared an apartment with girlfriend Dohrn and Weatherman advocates Gerry Long, Jeff Blum, Bob Tomashevsky, and Peter Clapp. He began traveling the country, visiting other SDS collectives to enforce the "party line," identify leaders, educate members in Marxist theory, and lecture on the need for violent action.

SDS continued to fragment throughout the summer. At an anti-racism conference titled "United Front Against Fascism," held from July 18-20 in Oakland, California

, the Black Panthers withdrew their support of SDS when it refused to sanction community control of the police in white neighborhoods. In August, most of the RYM II supporters left the organization as well (Klonsky denounced the Weatherman manifesto for arrogance, militancy and sectarianism on August 29 in an article in New Left Notes) and began planning their own series of national mass demonstrations for October 1969. Weatherman (or the Weather Bureau, as the new organization was sometimes beginning to be called) also began planning for an October 8-11 "National Action" built around Jacobs' slogan, "bring the war home," although by now the group probably had only about 300 total members nationwide. The National Action grew out of a resolution drafted by Jacobs and introduced at the October 1968 SDS National Council meeting in Boulder, Colorado

. The resolution, titled "The Elections Don't Mean Shit—Vote Where the Power Is—Our Power Is In The Street" and adopted by the council, was prompted by the success of the DNC protests in August 1968 and reflected Jacobs' strong advocacy of violence as a means of achieving political goals.

As part of the "National Action Staff," Jacobs was an integral part of the planning for what quickly came to be called "Four Days of Rage

." For Jacobs, the goal of the "Days of Rage" was clear: Weatherman would shove the war down

To help start the "all-out civil war", Bill Ayers bombed a statue commemorating the policemen killed in the 1886 Haymarket Affair

on the evening of October 6.

But the "Days of Rage" were a failure. Jacobs told the Black Panthers there would be 25,000 protesters in Chicago for the event, but no more than 200 showed up on the evening of Wednesday, October 8, 1969, in Chicago's Lincoln Park

, and perhaps half of them were members of Weatherman collectives from around the country. The crowd milled about for several hours, cold and uncertain. Late in the evening, Jacobs stood on the pedestal of the bombed Haymarket policemen's statue and declared: "We'll probably lose people today... We don't really have to win here ... just the fact that we are willing to fight the police is a political victory." Jacobs' speech was passionate and rousing as he compared the coming protest to the fight against fascism in World War II

:

Finally, at 10:25 p.m., Jeff Jones gave the pre-arranged signal over a bullhorn, and the Weatherman action began. Jacobs, Jones, David Gilbert and others led a charge south through the city toward the Drake Hotel

and the exceptionally affluent Gold Coast neighborhood, smashing windows in automobiles and buildings as they went. The mass of the crowd ran about four blocks before encountering police barricades. The mob charged the police but splintered into small groups, and more than 1,000 police counter-attacked. Although many protesters had—as J.J. did—motorcycle or football helmets on, the police were better trained and armed and nightsticks were expertly aimed to disable the rioters. Large amounts of tear gas were used, and at least twice police ran squad cars full speed into crowds. After only a half-hour or so, the riot was over: 28 policemen were injured (none seriously), six Weathermen were shot and an unknown number injured, and 68 protesters were arrested. Jacobs was arrested almost immediately.

For the next two days, Weatherman held no rallies or protests. Supporters of the RYM II movement, led by Klonsky and Noel Ignatin, held peaceful rallies of several hundred people in front of the federal courthouse, an International Harvester

factory, and Cook County Hospital

. The largest event of the Days of Rage occurred on Friday, October 9, when RYM II led an interracial march of 2,000 people through a Spanish-speaking part of Chicago.

On Saturday, October 10, Weatherman attempted to regroup and 'reignite the revolution'. About 300 protesters marched swiftly through The Loop

, Chicago's main business district, watched over by a double-line of heavily armed police. Led by Jacobs and other Weatherman members, the protesters suddenly broke through the police lines and rampaged through the Loop, smashing windows of cars and stores. But the police were ready, and quickly sealed off the protesters. Within 15 minutes, more than half the crowd had been arrested—one of the first, again, being Jacobs.

The 'Days of Rage' cost Chicago and the state of Illinois

about $183,000 ($100,000 for National Guard payroll, $35,000 in damages, and $20,000 for one injured citizen's medical expenses). Most of Weatherman and SDS' leaders were jailed, and the Weatherman bank account emptied of more than $243,000 in order to pay for bail.

s, stockpiling arms and explosives, identifying strategic targets to attack, and establishing a legitimate and legal organization to speak and provide legal representation for the underground. As the debate continued throughout the fall and early winter of 1969, Jacobs grew a pointed beard, ended his relationship with Dohrn, dated Weatherman Eleanor Raskin

and dropped acid with her.

From December 26 to December 31, 1969, Weatherman held the last of its National Council meetings in Flint, Michigan

. Flying to the event, Dohrn and Jacobs ran up and down the aisles of the airplane, seizing food, frightening the passengers. The meeting, dubbed the "War Council" by the 400 people who attended, adopted Jacobs' call for violent revolution. Dohrn opened the conference by telling the delegates they needed to stop being afraid and begin the "armed struggle." Reminding the delegates of the murder of Sharon Tate and four others on August 9, 1969 by members of the Manson Family

. "Dig it," Dohrn said approvingly. "First they killed those pigs, then they ate dinner in the same room with them, they even shoved a fork into a victim’s stomach! Wild!" She then held up three fingers in what she called the "Manson fork salute." Over the next five days, the participants met in informal, random groups to discuss what "going underground" meant, how best to organize collectives, and justifications for violence. In the evening, the groups reconvened for a mass "wargasm"—practicing karate

, engaging in physical exercise, singing songs, and listening to speeches. The "War Council" ended with a major speech by John Jacobs. J.J. condemned the "pacifism" of white middle-class American youth, a belief which they held because they were insulated from the violence which afflicted blacks and the poor. He predicted a successful revolution, and declared that youth were moving away from passivity and apathy and toward a new high-energy culture of "repersonalization" brought about by drugs, sex, and armed revolution. "We're against everything that's 'good and decent' in honky America," Jacobs said in his most oft-quoted statement. "We will burn and loot and destroy. We are the incubation of your mother's nightmare."

Two major decisions came out of the "War Council." The first was to immediately begin a violent, armed struggle against the state without attempting to organize or mobilize a broad swath of the public. The second was to create underground collectives in major cities throughout the country. In fact, Weatherman created only three significant, active collectives, one in California, the Midwest, and New York City. The New York City collective was led by Jacobs and Terry Robbins, and included Ted Gold

, Kathy Boudin

, Cathy Wilkerson (Robbins' girlfriend), and Diana Oughton

. Jacobs was one of Robbins' biggest supporters, and pushed Weatherman to let Robbins be as violent as he wanted to be. The Weatherman national leadership agreed, as did the New York City collective. The collective's first target was Judge John Murtagh, who was overseeing the trial of the "Panther 21". On February 21, 1970, the New York City collective planted a fire-bomb

outside Judge Murtagh's home. The device detonated, but did little damage. After this incident, the Federal Bureau of Investigation

began calling Jacobs one of the "most notorious" terrorists in the country. Robbins concluded the fire-bombs were unreliable, and turned toward using dynamite. The group began buying dynamite under false names from a variety of sources in the Northeast, and had soon acquired six cases of the explosive.

During the week of March 2, 1970, the collective moved into a townhouse at 18 West Eleventh Street in Greenwich Village

in New York City. The house belonged to James Platt Wilkerson, Cathy Wilkerson's father and a wealthy radio station owner. James Wilkerson was on vacation, and Cathy told her father she wanted to stay in the townhouse while she recovered from the flu. Reluctantly, James Wilkerson agreed. During the first few days in the townhouse, Robbins conceived a plan to bomb an officers' dance at Fort Dix in New Jersey

. Jacobs was embarrassed by Robbins' ranting about attacking a "strategic target" like a dance, but said nothing. According to other members of Weatherman who spoke with the group at the time, Robbins had lost touch with reality, and the other members of the group seemed incapable of making decisions.

On the morning of March 6, the collective began unloading several large, heavy boxes from a white station wagon and bringing them into the townhouse. A few minutes before noon, an explosion

in the townhouse basement tore the building apart. Two more large explosions followed, collapsing the front of the building. The ruptured gas mains below the building caught fire, consuming part of the structure. Robbins and Oughton, presumably assembling a bomb in the basement, died in the blast. Gold was trapped under falling beams and died from asphyxiation. Boudin, taking a shower at the time, fled the building naked. Wilkerson, who was dressing, ran from the rubble clad only in jeans. Anne Hoffman, wife of actor Dustin Hoffman

and the Wilkerson's next-door-neighbor (the Hoffman apartment was partially damaged in the blast), grabbed a shower curtain and covered Boudin with it. Susan Wager

, ex-wife of actor Henry Fonda

, rushed up the street and helped the two women to her home. Wager gave them both some clothes, but the two women fled. Jacobs was not in the townhouse at the time, and went into hiding after the blast.

Initially, the townhouse explosion appeared to have little effect on Jacobs. He continued to press for armed revolution, and even advocated that Weatherman establish roving bands of armed radicals to help start the revolution.

On April 2, 1970, Attorney General

John N. Mitchell

personally announced federal indictments against 11 members of Weatherman for their role in the Days of Rage. Included in the indictments was John Jacobs, who was accused of crossing state lines with intent to riot.

But other leaders in Weatherman began to reconsider armed struggle as a tactic. Dohrn called for a meeting in late April 1970 of all of Weatherman's top leadership at the collective safe house in Mendocino, California

, north of San Francisco

. Exhausted from months on the run, consumed by fear, and depressed by the deaths of Robbins, Oughton and Gold, the leadership agreed to lay some ground rules for the Mendocino debates. There would be no shouting, and no discussion of theory or philosophy in the evenings. Jacobs vehemently disagreed, and was largely excluded from the ensuing discussions. Over the next several days, the leaders of the Weather Underground discussed how to respond to the townhouse blast. After several days, the group concluded that Jacobs and Robbins had committed "the military error" by advocating armed revolution. As leader of the group, Dohrn had the power to expel Jacobs. She did so, and Jacobs left quietly. He never participated in radical activities again.

The Weatherman organization did not, however, immediately announce its decision. As early as May 21, 1970, it issued a communiqué announcing its continuing support for armed revolution in the United States. Several more communiqués followed throughout the year, as more Weatherman-sponsored bombings occurred across the country. It was not until December 6, 1970, that the group would condemn Jacobs' "military error." The renunciation of violence came in a statement titled "New Morning-Changing Weather." In that document, Dohrn called the townhouse blast "the military error" and renamed the organization a less-sexist "Weather Underground."

Jacobs wandered in northern California and Mexico for several years under several aliases, taking drugs and drinking heavily. He was almost captured once in California, but escaped by climbing out a window and escaping across a roof. Jacobs traveled to Canada, where his older brother was attending Simon Fraser University

. The two did not meet often, in part because they looked alike but also because the FBI and Royal Canadian Mounted Police

were still watching Robert in the hopes JJ would visit him. Jacobs first settled on Vancouver Island

, British Columbia

, and worked at planting trees—donating most of his money to the building of a Buddhist

temple on nearby Saltspring Island

.

Jacobs soon moved to the mainland and settled in the city of Vancouver

, where he took the name "Wayne Curry." He met his first life partner

there, and he and the woman had two children by 1977. The relationship ended in the early 1980s, and Jacobs lived alone for several years. He continued to harbor a bitter hatred of police, and began taking cocaine

. In 1986, Jacobs met and began living with Marion MacPherson. Jacobs worked at various blue-collar jobs, including stonecutter and construction worker, and made extra money selling marijuana. The couple became common law husband and wife

, and raised four children (some from MacPherson's prior marriage).

Jacobs took courses in Third World

politics and history at several local colleges and universities, receiving grades of A's and B's. He spent much of his free time gardening or reading, and although acquaintances unwittingly urged him to become involved in political activity he refused. He spent much of his time in his basement, reading newspapers and clipping articles (especially those which told of his former Weatherman comrades resurfacing and reintegrating back into society).

In 1996, Jacobs was diagnosed with melanoma

. The cancer soon spread to his brain, lungs, and lymph nodes, and his skin became painfully sensitive to the slightest touch.

The U.S. Department of Justice dropped its federal warrant against Jacobs in October 1979.

John Jacobs died on October 20, 1997, of complications related to melanoma. He fell ill on October 19, and police and medical personnel were called to his home by his wife. When police officers inadvertently touched his sensitive skin (despite his wife's caution not to), he became violent and beat several officers before being subdued. Jacobs died the next day.

Jacobs was cremated. Some of his ashes were spread in his backyard, some in English Bay, and some in Oregon

(near a place he had visited while on the run). Some of his ashes were also taken to Cuba

and spread near the mausoleum

of Che Guevara. A photo of Jacobs from the late 1960s is attached to a plaque next to the site. An extensive statement, documenting Jacobs' life, is written on the plaque. It ends with the statement: "He wanted to live like Che. Let him rest with Che."

.

In the fiction novel American Pastoral

by Philip Roth

, the daughter of the central character appears to be a member of the Weather Underground. The novel incorporates Jacobs' "We're against everything that's 'good and decent'..." statement at the 1969 "War Council" in Flint.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

student

Student activism

Student activism is work done by students to effect political, environmental, economic, or social change. It has often focused on making changes in schools, such as increasing student influence over curriculum or improving educational funding...

and anti-war

Anti-war

An anti-war movement is a social movement, usually in opposition to a particular nation's decision to start or carry on an armed conflict, unconditional of a maybe-existing just cause. The term can also refer to pacifism, which is the opposition to all use of military force during conflicts. Many...

activist in the 1960s and early 1970s. He was a leader in both Students for a Democratic Society

Students for a Democratic Society (1960 organization)

Students for a Democratic Society was a student activist movement in the United States that was one of the main iconic representations of the country's New Left. The organization developed and expanded rapidly in the mid-1960s before dissolving at its last convention in 1969...

and the Weatherman

Weather Underground (organization)

Weatherman, known colloquially as the Weathermen and later the Weather Underground Organization , was an American radical left organization. It originated in 1969 as a faction of Students for a Democratic Society composed for the most part of the national office leadership of SDS and their...

group, and an advocate of the use of violent force to overthrow the government of the United States. A fugitive since 1970, he died of melanoma in 1997.

Early life

John Jacobs was born to Douglas and Lucille Jacobs, a prominent leftist Jewish couple, in New York state in 1947. He had an older brother, Robert. His father was a well-known leftistLeft-wing politics

In politics, Left, left-wing and leftist generally refer to support for social change to create a more egalitarian society...

journalist

Journalism

Journalism is the practice of investigation and reporting of events, issues and trends to a broad audience in a timely fashion. Though there are many variations of journalism, the ideal is to inform the intended audience. Along with covering organizations and institutions such as government and...

who had been one of the first Americans to report on the Spanish Civil War

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil WarAlso known as The Crusade among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War among Carlists, and The Rebellion or Uprising among Republicans. was a major conflict fought in Spain from 17 July 1936 to 1 April 1939...

. His parents later moved to Connecticut

Connecticut

Connecticut is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, and the state of New York to the west and the south .Connecticut is named for the Connecticut River, the major U.S. river that approximately...

, where his father owned a bookstore. His childhood appeared to have been happy, and he was close to his parents.

In high school, Jacobs began to read Marxist

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

philosophy heavily, and was deeply interested in the Russian Revolution of 1917. He also admired Che Guevara

Che Guevara

Ernesto "Che" Guevara , commonly known as el Che or simply Che, was an Argentine Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, intellectual, guerrilla leader, diplomat and military theorist...

.

Jacobs graduated from high school in 1965 and enrolled at Columbia College of Columbia University

Columbia College of Columbia University

Columbia College is the oldest undergraduate college at Columbia University, situated on the university's main campus in Morningside Heights in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It was founded in 1754 by the Church of England as King's College, receiving a Royal Charter from King George II...

. During the summer between high school and college, he lived in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

and worked for a left-wing newspaper. Politically active in leftist political circles, Jacobs became acquainted with a large number of progressive intellectuals who further stimulated growth in his political ideology. For a brief time, he belonged to the Progressive Labor Party (PL), at the time a Maoist

Maoism

Maoism, also known as the Mao Zedong Thought , is claimed by Maoists as an anti-Revisionist form of Marxist communist theory, derived from the teachings of the Chinese political leader Mao Zedong . Developed during the 1950s and 1960s, it was widely applied as the political and military guiding...

communist party

Communist party

A political party described as a Communist party includes those that advocate the application of the social principles of communism through a communist form of government...

. His first semester at Columbia, Jacobs met fellow freshman Mark Rudd

Mark Rudd

Mark William Rudd is a political organizer, mathematics instructor, and anti-war activist, most well known for his involvement with the Weather Underground. Rudd became a member of the Columbia University chapter of Students for a Democratic Society in 1963. By 1968, he had emerged as a leader...

, and the two became friends.

Rise and role in Students for a Democratic Society

J.J., as most people at Columbia called him, soon joined Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). The Columbia University chapter of SDS had been founded in the 1950s as part of the Student League for Industrial Democracy, the youth arm of the League for Industrial DemocracyLeague for Industrial Democracy

The League for Industrial Democracy , from 1960-1965 known as the Students for a Democratic Society , was founded in 1905 by a group of notable socialists including Harry W. Laidler, Jack London, Norman Thomas, Upton Sinclair, and J.G. Phelps Stokes...

(a social democratic

Social democracy

Social democracy is a political ideology of the center-left on the political spectrum. Social democracy is officially a form of evolutionary reformist socialism. It supports class collaboration as the course to achieve socialism...

organization co-founded by Jack London

Jack London

John Griffith "Jack" London was an American author, journalist, and social activist. He was a pioneer in the then-burgeoning world of commercial magazine fiction and was one of the first fiction writers to obtain worldwide celebrity and a large fortune from his fiction alone...

, Norman Thomas

Norman Thomas

Norman Mattoon Thomas was a leading American socialist, pacifist, and six-time presidential candidate for the Socialist Party of America.-Early years:...

, Upton Sinclair

Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. , was an American author who wrote close to one hundred books in many genres. He achieved popularity in the first half of the twentieth century, acquiring particular fame for his classic muckraking novel, The Jungle . It exposed conditions in the U.S...

and others). The chapter had sputtered for years, but became active in 1965 when it became known as SDS). Jacobs became very active in the group. A series of protests against on-campus military, CIA

Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency is a civilian intelligence agency of the United States government. It is an executive agency and reports directly to the Director of National Intelligence, responsible for providing national security intelligence assessment to senior United States policymakers...

and corporate

Military-industrial complex

Military–industrial complex , or Military–industrial-congressional complex is a concept commonly used to refer to policy and monetary relationships between legislators, national armed forces, and the industrial sector that supports them...

recruitment and ROTC

Reserve Officers' Training Corps

The Reserve Officers' Training Corps is a college-based, officer commissioning program, predominantly in the United States. It is designed as a college elective that focuses on leadership development, problem solving, strategic planning, and professional ethics.The U.S...

induction ceremonies rocked Columbia's campus for the next two years. Jacobs organized a protest in February 1967 against CIA recruiting at Columbia. Initially, the SDS chapter disavowed the action. But when Jacobs' sit-in proved popular among Columbia students, SDS claimed J.J. as one of their own. The CIA protest led to Jacobs' rapid rise within the chapter. The protests led Columbia President Grayson L. Kirk

Grayson L. Kirk

Grayson Louis Kirk was president of Columbia University during the Columbia University protests of 1968. He was also a Professor of Government, advisor to the State Department, and instrumental in the formation of the United Nations.-Early life:Kirk was born to a farmer and schoolteacher in...

to ban indoor protests at Columbia beginning in September 1967.

In March 1967, SDS member Bob Feldman accidentally discovered documents in a campus library detailing Columbia's affiliation with the Institute for Defense Analyses

Institute for Defense Analyses

The Institute for Defense Analyses is a non-profit corporation that administers three federally funded research and development centers to assist the United States government in addressing important national security issues, particularly those requiring scientific and technical expertise...

(IDA), a weapons research think-tank affiliated with the Department of Defense

United States Department of Defense

The United States Department of Defense is the U.S...

. Jacobs participated in the protests against the IDA, and was put on academic probation

Academic probation

Academic probation in the United Kingdom is a period served by a new staff member at a university or college when they are first given their job. It is specified in the conditions of employment of the staff member, and may vary from person to person and from institution to institution...

for violating President Kirk's ban on indoor protests. Despite its growing influence on campus, the SDS chapter was deeply divided. One group of SDSers, called the "Praxis Axis," advocated more organizing and nonviolence. A second group, the "Action Faction," called for more aggressive action. In the early spring 1968, the Action Faction took control of Columbia University's SDS chapter. Jacobs was an active member of the Action Faction, and soon became one of its leaders. When Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was an American clergyman, activist, and prominent leader in the African-American Civil Rights Movement. He is best known for being an iconic figure in the advancement of civil rights in the United States and around the world, using nonviolent methods following the...

was assassinated on April 4, 1968, riots broke out in many American cities. Jacobs wandered the streets of Harlem

Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in the New York City borough of Manhattan, which since the 1920s has been a major African-American residential, cultural and business center. Originally a Dutch village, formally organized in 1658, it is named after the city of Haarlem in the Netherlands...

alone for most of the night, thrilled by the violence and inability of the police to maintain order. He adopted Georges Danton's

Georges Danton

Georges Jacques Danton was leading figure in the early stages of the French Revolution and the first President of the Committee of Public Safety. Danton's role in the onset of the Revolution has been disputed; many historians describe him as "the chief force in theoverthrow of the monarchy and the...

dictum of "Audacity, audacity, and more audacity!" as his own motto.

Columbia protests of 1968

The opportunity for Jacobs to participate more fully in direct actionDirect action

Direct action is activity undertaken by individuals, groups, or governments to achieve political, economic, or social goals outside of normal social/political channels. This can include nonviolent and violent activities which target persons, groups, or property deemed offensive to the direct action...

came just days after King's death. Columbia University officials were planning to build a new gymnasium on the south side of the campus. The building, which would have straddled a hill, would have two entrances—one on the north, upper side for students and one on the south, lower side for residents of Morningside Heights

Morningside Heights, Manhattan

Morningside Heights is a neighborhood of the Borough of Manhattan in New York City and is chiefly known as the home of institutions such as Columbia University, Teachers College, Barnard College, the Manhattan School of Music, Bank Street College of Education, the Cathedral of Saint John the...

, a mostly African American

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

neighborhood. To many students and local residents, it seemed as if Columbia were permitting blacks to use the gym, but only if they entered through the back door. On April 23, 1968, Rudd, Jacobs, and other members of Columbia's SDS chapter led a group of about 500 people in a protest against the gymnasium at the university Sundial. Part of the crowd attempted to take over Low Memorial Library

Low Memorial Library

The Low Memorial Library is the administrative center of Columbia University. Built in 1895 by University President Seth Low in memory of his father, Abiel Abbot Low, and financed with $1 million of Low's own money due to the recalcitrance of university alumni, it is the focal point and most...

, but were repulsed by a counter-demonstration of conservative students. Some students tore down the fence surrounding the construction site, and were arrested by New York City police. Rudd then shouted that the crowd should seize Hamilton Hall

Hamilton Hall (Columbia University)

Hamilton Hall is an academic building on the Morningside Heights campus of Columbia University in the City of New York. The building is named for Alexander Hamilton, one of the most famous attendees of King's College, Columbia's predecessor...

. The mob took over the building, taking a dean hostage. A number of militant young African Americans from Harlem

Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in the New York City borough of Manhattan, which since the 1920s has been a major African-American residential, cultural and business center. Originally a Dutch village, formally organized in 1658, it is named after the city of Haarlem in the Netherlands...

(rumored to be carrying guns) entered the building throughout the night and ordered the white students out. The Caucasian students seized Low Memorial Library. Over the next week, more than 1,000 Columbia students joined the protest and seized three more buildings. Jacobs led the seizure of Mathematics Hall. Among the protesters was Tom Hayden

Tom Hayden

Thomas Emmet "Tom" Hayden is an American social and political activist and politician, known for his involvement in the animal rights, and the anti-war and civil rights movements of the 1960s. He is the former husband of actress Jane Fonda and the father of actor Troy Garity.-Life and...

, who arrived from Newark, New Jersey

Newark, New Jersey

Newark is the largest city in the American state of New Jersey, and the seat of Essex County. As of the 2010 United States Census, Newark had a population of 277,140, maintaining its status as the largest municipality in New Jersey. It is the 68th largest city in the U.S...

, where he had been organizing poor inner-city residents. Rudd, Jacobs, Hayden and others organized communes inside the buildings, and educated the students in the theories of Marxism, racism

Racism

Racism is the belief that inherent different traits in human racial groups justify discrimination. In the modern English language, the term "racism" is used predominantly as a pejorative epithet. It is applied especially to the practice or advocacy of racial discrimination of a pernicious nature...

, and imperialism

Imperialism

Imperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

. Columbia University refused to grant the protesters' demands regarding the gymnasium or amnesty for those who had seized the buildings. When the police were sent in to clear the buildings after a week, they brutally beat and clubbed hundreds of students. Jacobs suggested putting Columbia's rare Ming Dynasty vases in the windows to prevent sniper attacks, and pushing police out of windows. Black students in Hamilton Hall had contacted civil rights lawyers, who had arranged to be on-site during the arrests and for the students to leave Hamilton Hall peacefully. Angered by the lack of police violence, Jacobs set fire to a professor's office in Hamilton, an incident later blamed on the police. Thousands of students went on strike the next week, refusing to attend classes, and the university canceled final exams. The events catapulted Rudd into national prominence, and Rudd and Jacobs became national leaders in SDS. Jacobs began using the phrase "bring the war home," and it was widely adopted within the anti-war movement.

As college students across America began demanding "two, three, many Columbias," Jacobs became a recognized national leader of SDS and looked to by those who saw violence as the only way to respond to the governing political and economic system of the day. Jacobs began to look the part of a counterculture leader as well. In the middle of 1968, he began wearing tight jeans, a leather jacket, and a gold chain with a lion's tooth, and slicked his hair back 1950s-style to purposefully distinguish himself from the clean-cut, middle-class students who attended most anti-war protests. He became one of SDS' earliest and most prominent ideological thinkers, and was widely recognized as a charismatic persuasive speaker.

At the SDS national convention in East Lansing, Michigan

East Lansing, Michigan

East Lansing is a city in the U.S. state of Michigan. The city is located directly east of Lansing, Michigan, the state's capital. Most of the city is within Ingham County, though a small portion lies in Clinton County. The population was 48,579 at the time of the 2010 census, an increase from...

, in June 1968, Jacobs' thinking began to become even more radical. The East Lansing convention is best known for the interminable debates and ferocious parliamentary battles between the SDS National Office leadership (led by Michael Klonsky

Michael Klonsky

Michael Klonsky is an American educator, author, and political activist. He is known for his work with the Students for a Democratic Society, the New Communist Movement, and, later, the small schools movement.-Political activism:...

and Bernardine Dohrn

Bernardine Dohrn

Bernardine Rae Dohrn is a former leader of the American anti-Vietnam War radical organization, Weather Underground. She is an Associate Professor of Law at Northwestern University School of Law and the immediate past Director of Northwestern's Children and Family Justice Center...

) and the delegates from PL-controlled SDS chapters around the country.

Robin Palmer, an ex-Yippie

Youth International Party

The Youth International Party, whose members were commonly called Yippies, was a radically youth-oriented and countercultural revolutionary offshoot of the free speech and anti-war movements of the 1960s. It was founded on Dec. 31, 1967...

had drifted into SDS. Palmer argued, contrary to current SDS thinking, that President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Richard Nixon's

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. The only president to resign the office, Nixon had previously served as a US representative and senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961 under...

"silent majority" did exist. Most Americans, Palmer said, would not oppose imperialism

Imperialism

Imperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

, militarism

Militarism

Militarism is defined as: the belief or desire of a government or people that a country should maintain a strong military capability and be prepared to use it aggressively to defend or promote national interests....

and capitalism

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

if they were only shown the truth. Rather, most Americans knew the truth, and supported these ideologies actively and whole-heartedly. One of the Old Left's slogans had been "Serve the People." Convinced Palmer was correct, Jacobs proposed at the June 1968 convention that SDS adopt the slogan "Serve the People Shit" to reflect the public's support for greed and war.

Role in Weatherman

SDS had opposed the call for mass demonstrations at the 1968 Democratic National Convention1968 Democratic National Convention

The 1968 Democratic National Convention of the U.S. Democratic Party was held at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois, from August 26 to August 29, 1968. Because Democratic President Lyndon Johnson had announced he would not seek a second term, the purpose of the convention was to...

in Chicago

Chicago

Chicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

, Illinois

Illinois

Illinois is the fifth-most populous state of the United States of America, and is often noted for being a microcosm of the entire country. With Chicago in the northeast, small industrial cities and great agricultural productivity in central and northern Illinois, and natural resources like coal,...

. The group felt that mass demonstrations and electoral politics were not effective as a means of influencing national policy. But when the demonstrations proved popular and provoked a heavy-handed police response (as SDS predicted), the organization moved quickly to take credit for the protests.

But SDS itself was suffering from extreme factionalism. Since 1963, the Progressive Labor Party (PL) had been infiltrating its members into SDS in the hopes of convincing SDSers to join the party. Although only a tiny minority of SDS membership nationwide, PL supporters (with the support of the national party) often constituted a quarter or more of the delegates to national SDS conventions. Strongly disciplined and skilled at 'entryism

Entryism

Entryism is a political tactic by which an organisation or state encourages its members or agents to infiltrate another organisation in an attempt to gain recruits, or take over entirely...

' and using parliamentary procedure, the PL supporters sought to seize control of SDS and turn the organization to the party's goals.

SDS leadership subsequently adopted a new policy in 1968 aimed at ending the factionalism. As the SDS National Council meeting convened in December 1968, National Secretary Mike Klonsky

Michael Klonsky

Michael Klonsky is an American educator, author, and political activist. He is known for his work with the Students for a Democratic Society, the New Communist Movement, and, later, the small schools movement.-Political activism:...

published an article in the New Left Notes (SDS' newsletter) titled "Toward A Revolutionary Youth Movement

Revolutionary Youth Movement

The Revolutionary Youth Movement was the section of Students for a Democratic Society that opposed the Worker Student Alliance of the Progressive Labor Party...

." A central document in SDS' final year, Klonsky's article advocated that SDS openly align itself with the working class and begin engaging in direct action

Direct action

Direct action is activity undertaken by individuals, groups, or governments to achieve political, economic, or social goals outside of normal social/political channels. This can include nonviolent and violent activities which target persons, groups, or property deemed offensive to the direct action...

. The goal of SDS should be to build class consciousness

Class consciousness

Class consciousness is consciousness of one's social class or economic rank in society. From the perspective of Marxist theory, it refers to the self-awareness, or lack thereof, of a particular class; its capacity to act in its own rational interests; or its awareness of the historical tasks...

among students by organizing working people and moving off campus, and by attacking racism

Racism

Racism is the belief that inherent different traits in human racial groups justify discrimination. In the modern English language, the term "racism" is used predominantly as a pejorative epithet. It is applied especially to the practice or advocacy of racial discrimination of a pernicious nature...

, militarism

Militarism

Militarism is defined as: the belief or desire of a government or people that a country should maintain a strong military capability and be prepared to use it aggressively to defend or promote national interests....

and the reactionary use of state police power. The "Revolutionary Youth Movement" (RYM) proposal was aimed squarely at PL, staking out some of the party's positions as the leadership's own while denouncing PL as deviant on others. The policy provoked five days of fierce debate, even shouting matches, between SDS' national leadership and supporters of PL. But on December 31, 1968, it passed and became national SDS policy.

Jacobs, however, felt that the RYM was insufficient. Within weeks of its adoption, he was hard at work on a new document which pushed the theoretical envelope even further. Jacobs was joined by several other SDS leaders, including Rudd, Dohrn, Jeff Jones

Jeff Jones (activist)

Jeff Jones is an environmental activist and consultant in Upstate New York. He was a national officer in Students for a Democratic Society, a founding member of Weatherman, and a leader of the Weather Underground....

, Bill Ayers

Bill Ayers

William Charles "Bill" Ayers is an American elementary education theorist and a former leader in the movement that opposed U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. He is known for his 1960s activism as well as his current work in education reform, curriculum, and instruction...

, Terry Robbins

Terry Robbins

Terry Robbins was a U.S. leftist radical activist. A key member of the Students for a Democratic Society Ohio chapter, he led Kent State into its first militant student uprising in 1968. Robbins was credited for drawing inspiration from Bob Dylan’s song Subterranean Homesick Blues which later...

and five others. Throughout April and May, Jacobs and the others worked on the document. They met with RYM supporters in the Northeast and Midwest, as well as with more mainstream SDSers.

When the SDS National Convention opened in Chicago on June 18, 1969, Jacobs' manifesto, "You Don't Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows," was published in the SDS newspaper, New Left Notes. Although the other 10 SDS leaders had contributed to the document, Jacobs was the primary author of what came to be called the "Weatherman manifesto." Robbins suggested the title, lifted from a line in the Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan is an American singer-songwriter, musician, poet, film director and painter. He has been a major and profoundly influential figure in popular music and culture for five decades. Much of his most celebrated work dates from the 1960s when he was an informal chronicler and a seemingly...

song "Subterranean Homesick Blues

Subterranean Homesick Blues

"Subterranean Homesick Blues" is a song by Bob Dylan, originally released in 1965 as a single on Columbia Records, catalogue 43242. It appeared 19 days later as the lead track to the album Bringing It All Back Home. It was Dylan's first Top 40 hit, peaking at #39 on the Billboard Hot 100. It also...

." Jacobs and 15 others signed it.

The "Weatherman" statement denounced imperialism and racism, and repudiated PL's claim that youth culture was bourgeois. The Weatherman manifesto also called for revolutionary violence at home to stop imperialism, and the formation of collectives in major cities to support the military struggle and stop factionalism. The Weatherman faction counted on RYM supporters to help them not only control the convention but also to pass the Weatherman manifesto. But Klonsky, Bob Avakian

Bob Avakian

Bob Avakian is Chairman of the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA , which he has led since its formation in 1975. He is a veteran of the Free Speech Movement and the Left of the 1960s and early 1970s, and was closely associated with the Black Panther Party. He has published writings on Marxism and...

, and Les Coleman—all key members of the pro-RYM caucus—disagreed with many of the positions advocated in the Weatherman statement. They issued their own position paper, "Revolutionary Youth Movement II" (RYM II). Although the Weatherman and RYM II factions were opposed to PL and nearly constituted a majority of delegates, they still lost control of the convention. Leaders of the Black Panther Party

Black Panther Party

The Black Panther Party wasan African-American revolutionary leftist organization. It was active in the United States from 1966 until 1982....

made an appearance designed to attack PL supporters on the issue of racism. But when the Panthers made references to "pussy power," they and the SDS leadership were accused of male chauvinism. The next day, the Panthers accused PL of deviating from "true" Marxism-Leninism. PL leaders accused the Panthers and SDS leadership of redbaiting. Dohrn, Rudd, Jacobs, Klonsky and Robbins huddled in an attempt to strategize a way to defeat the PL faction. Dohrn took to the podium and demanded that all "true" SDSers follow her out of the convention hall. Gathering in an adjoining hall, Dohrn demanded that SDS expel all PL supporters. On June 20, the Weatherman and RYM II caucuses re-entered the main convention hall, accused the PL supporters of racism and being insufficiently opposed to imperialism, and demanded that all PL supporters be ejected. When they were not, Dohrn, Rudd, Jacobs and the other national leaders led approximately two-thirds of the delegates out of the convention hall.

After the split in SDS, The Weatherman/RYM II faction began establishing collectives in cities around the country. Jacobs moved to Chicago. There, he shared an apartment with girlfriend Dohrn and Weatherman advocates Gerry Long, Jeff Blum, Bob Tomashevsky, and Peter Clapp. He began traveling the country, visiting other SDS collectives to enforce the "party line," identify leaders, educate members in Marxist theory, and lecture on the need for violent action.

Days of Rage

SDS continued to fragment throughout the summer. At an anti-racism conference titled "United Front Against Fascism," held from July 18-20 in Oakland, California

Oakland, California

Oakland is a major West Coast port city on San Francisco Bay in the U.S. state of California. It is the eighth-largest city in the state with a 2010 population of 390,724...

, the Black Panthers withdrew their support of SDS when it refused to sanction community control of the police in white neighborhoods. In August, most of the RYM II supporters left the organization as well (Klonsky denounced the Weatherman manifesto for arrogance, militancy and sectarianism on August 29 in an article in New Left Notes) and began planning their own series of national mass demonstrations for October 1969. Weatherman (or the Weather Bureau, as the new organization was sometimes beginning to be called) also began planning for an October 8-11 "National Action" built around Jacobs' slogan, "bring the war home," although by now the group probably had only about 300 total members nationwide. The National Action grew out of a resolution drafted by Jacobs and introduced at the October 1968 SDS National Council meeting in Boulder, Colorado

Boulder, Colorado

Boulder is the county seat and most populous city of Boulder County and the 11th most populous city in the U.S. state of Colorado. Boulder is located at the base of the foothills of the Rocky Mountains at an elevation of...

. The resolution, titled "The Elections Don't Mean Shit—Vote Where the Power Is—Our Power Is In The Street" and adopted by the council, was prompted by the success of the DNC protests in August 1968 and reflected Jacobs' strong advocacy of violence as a means of achieving political goals.

As part of the "National Action Staff," Jacobs was an integral part of the planning for what quickly came to be called "Four Days of Rage

Days of Rage

The Days of Rage demonstrations were a series of direct actions taken over a course of three days in October 1969 in Chicago organized by the Weatherman faction of the Students for a Democratic Society...

." For Jacobs, the goal of the "Days of Rage" was clear: Weatherman would shove the war down

their dumb, fascist throats and show them, while we were at it, how much better we were than them, both tactically and strategically, as a people. In an all-out civil war over Vietnam and other fascist U.S. imperialism, we were going to bring the war home. 'Turn the imperialists' war into a civil war', in Lenin's words. And we were going to kick ass.

To help start the "all-out civil war", Bill Ayers bombed a statue commemorating the policemen killed in the 1886 Haymarket Affair

Haymarket affair

The Haymarket affair was a demonstration and unrest that took place on Tuesday May 4, 1886, at the Haymarket Square in Chicago. It began as a rally in support of striking workers. An unknown person threw a dynamite bomb at police as they dispersed the public meeting...

on the evening of October 6.

But the "Days of Rage" were a failure. Jacobs told the Black Panthers there would be 25,000 protesters in Chicago for the event, but no more than 200 showed up on the evening of Wednesday, October 8, 1969, in Chicago's Lincoln Park

Lincoln Park

Lincoln Park is an urban park in Chicago, which gave its name to the Lincoln Park, Chicago community area.Lincoln Park may also refer to:-Urban parks:*Lincoln Park , California*Lincoln Park, San Francisco, California...

, and perhaps half of them were members of Weatherman collectives from around the country. The crowd milled about for several hours, cold and uncertain. Late in the evening, Jacobs stood on the pedestal of the bombed Haymarket policemen's statue and declared: "We'll probably lose people today... We don't really have to win here ... just the fact that we are willing to fight the police is a political victory." Jacobs' speech was passionate and rousing as he compared the coming protest to the fight against fascism in World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

:

There is a war in Vietnam and we are a Vietnam within America. We are small but we have stepped in the way of history. We are going to change this country. ... The battle of Vietnam is one battle in the world revolution. It is the Stalingrad of American imperialism. We are part of that Stalingrad. We are the guerrillas fighting behind enemy lines. ... We will not commit suicide. We will not fight here. We will march to where we are within the symbol-the very pig fascist architecture. ... But we will make a political stand today.

Finally, at 10:25 p.m., Jeff Jones gave the pre-arranged signal over a bullhorn, and the Weatherman action began. Jacobs, Jones, David Gilbert and others led a charge south through the city toward the Drake Hotel

Drake Hotel

Drake Hotel may refer to:in Canada*Drake Hotel in the United States *Drake Hotel , Illinois, listed on the NRHP*Drake Hotel , listed on the NRHP in New Mexico*Drake Hotel...

and the exceptionally affluent Gold Coast neighborhood, smashing windows in automobiles and buildings as they went. The mass of the crowd ran about four blocks before encountering police barricades. The mob charged the police but splintered into small groups, and more than 1,000 police counter-attacked. Although many protesters had—as J.J. did—motorcycle or football helmets on, the police were better trained and armed and nightsticks were expertly aimed to disable the rioters. Large amounts of tear gas were used, and at least twice police ran squad cars full speed into crowds. After only a half-hour or so, the riot was over: 28 policemen were injured (none seriously), six Weathermen were shot and an unknown number injured, and 68 protesters were arrested. Jacobs was arrested almost immediately.

For the next two days, Weatherman held no rallies or protests. Supporters of the RYM II movement, led by Klonsky and Noel Ignatin, held peaceful rallies of several hundred people in front of the federal courthouse, an International Harvester

International Harvester

International Harvester Company was a United States agricultural machinery, construction equipment, vehicle, commercial truck, and household and commercial products manufacturer. In 1902, J.P...

factory, and Cook County Hospital

John H. Stroger, Jr. Hospital of Cook County

The John H. Stroger, Jr. Hospital of Cook County, formerly Cook County Hospital is a public urban teaching hospital in Chicago that provides primary, specialty and tertiary healthcare services to the five million residents of Cook County, Illinois. The hospital has a staff of 300 attending...

. The largest event of the Days of Rage occurred on Friday, October 9, when RYM II led an interracial march of 2,000 people through a Spanish-speaking part of Chicago.

On Saturday, October 10, Weatherman attempted to regroup and 'reignite the revolution'. About 300 protesters marched swiftly through The Loop

Chicago Loop

The Loop or Chicago Loop is one of 77 officially designated Chicago community areas located in the City of Chicago, Illinois. It is the historic commercial center of downtown Chicago...

, Chicago's main business district, watched over by a double-line of heavily armed police. Led by Jacobs and other Weatherman members, the protesters suddenly broke through the police lines and rampaged through the Loop, smashing windows of cars and stores. But the police were ready, and quickly sealed off the protesters. Within 15 minutes, more than half the crowd had been arrested—one of the first, again, being Jacobs.

The 'Days of Rage' cost Chicago and the state of Illinois

Illinois

Illinois is the fifth-most populous state of the United States of America, and is often noted for being a microcosm of the entire country. With Chicago in the northeast, small industrial cities and great agricultural productivity in central and northern Illinois, and natural resources like coal,...

about $183,000 ($100,000 for National Guard payroll, $35,000 in damages, and $20,000 for one injured citizen's medical expenses). Most of Weatherman and SDS' leaders were jailed, and the Weatherman bank account emptied of more than $243,000 in order to pay for bail.

Going underground and the townhouse explosion

Although the Days of Rage were an unabashed failure, Jacobs urged Weatherman to carry on the struggle. He urged that the Weatherman organization "go underground"—adopting secret identities, setting up safe houseSafe house

In the jargon of law enforcement and intelligence agencies, a safe house is a secure location, suitable for hiding witnesses, agents or other persons perceived as being in danger...

s, stockpiling arms and explosives, identifying strategic targets to attack, and establishing a legitimate and legal organization to speak and provide legal representation for the underground. As the debate continued throughout the fall and early winter of 1969, Jacobs grew a pointed beard, ended his relationship with Dohrn, dated Weatherman Eleanor Raskin

Eleanor Raskin

Eleanor E. Raskin née Stein; was a member of Weatherman. She is currently an associate professor at Albany Law School, teaching transnational environmental law with a focus on catastrophic climate change.- Early life :Eleanor E...

and dropped acid with her.

From December 26 to December 31, 1969, Weatherman held the last of its National Council meetings in Flint, Michigan

Flint, Michigan

Flint is a city in the U.S. state of Michigan and is located along the Flint River, northwest of Detroit. The U.S. Census Bureau reports the 2010 population to be placed at 102,434, making Flint the seventh largest city in Michigan. It is the county seat of Genesee County which lies in the...

. Flying to the event, Dohrn and Jacobs ran up and down the aisles of the airplane, seizing food, frightening the passengers. The meeting, dubbed the "War Council" by the 400 people who attended, adopted Jacobs' call for violent revolution. Dohrn opened the conference by telling the delegates they needed to stop being afraid and begin the "armed struggle." Reminding the delegates of the murder of Sharon Tate and four others on August 9, 1969 by members of the Manson Family

Charles Manson

Charles Milles Manson is an American criminal who led what became known as the Manson Family, a quasi-commune that arose in California in the late 1960s. He was found guilty of conspiracy to commit the Tate/LaBianca murders carried out by members of the group at his instruction...

. "Dig it," Dohrn said approvingly. "First they killed those pigs, then they ate dinner in the same room with them, they even shoved a fork into a victim’s stomach! Wild!" She then held up three fingers in what she called the "Manson fork salute." Over the next five days, the participants met in informal, random groups to discuss what "going underground" meant, how best to organize collectives, and justifications for violence. In the evening, the groups reconvened for a mass "wargasm"—practicing karate

Karate

is a martial art developed in the Ryukyu Islands in what is now Okinawa, Japan. It was developed from indigenous fighting methods called and Chinese kenpō. Karate is a striking art using punching, kicking, knee and elbow strikes, and open-handed techniques such as knife-hands. Grappling, locks,...

, engaging in physical exercise, singing songs, and listening to speeches. The "War Council" ended with a major speech by John Jacobs. J.J. condemned the "pacifism" of white middle-class American youth, a belief which they held because they were insulated from the violence which afflicted blacks and the poor. He predicted a successful revolution, and declared that youth were moving away from passivity and apathy and toward a new high-energy culture of "repersonalization" brought about by drugs, sex, and armed revolution. "We're against everything that's 'good and decent' in honky America," Jacobs said in his most oft-quoted statement. "We will burn and loot and destroy. We are the incubation of your mother's nightmare."

Two major decisions came out of the "War Council." The first was to immediately begin a violent, armed struggle against the state without attempting to organize or mobilize a broad swath of the public. The second was to create underground collectives in major cities throughout the country. In fact, Weatherman created only three significant, active collectives, one in California, the Midwest, and New York City. The New York City collective was led by Jacobs and Terry Robbins, and included Ted Gold

Ted Gold

Theodore "Ted" Gold was a member of Weatherman.-Early years and education:Gold was a red diaper baby. He was the son of Hyman Gold, a prominent Jewish physician and a mathematics instructor at Columbia University who had both been part of the Old Left. His mother was a statistician who taught at...

, Kathy Boudin

Kathy Boudin

Kathy Boudin is a former American radical who was convicted in 1984 of felony murder for her participation in an armed robbery that resulted in the killing of three people. She later became a public health expert while in prison...

, Cathy Wilkerson (Robbins' girlfriend), and Diana Oughton

Diana Oughton

Diana Oughton was a member of the Students for a Democratic Society Michigan Chapter and later, a member of the 1960s radical group Weatherman. Oughton received her B.A. from Bryn Mawr College. After graduation, Oughton went to Guatemala with the VISA program to teach the young and older...

. Jacobs was one of Robbins' biggest supporters, and pushed Weatherman to let Robbins be as violent as he wanted to be. The Weatherman national leadership agreed, as did the New York City collective. The collective's first target was Judge John Murtagh, who was overseeing the trial of the "Panther 21". On February 21, 1970, the New York City collective planted a fire-bomb

Incendiary device

Incendiary weapons, incendiary devices or incendiary bombs are bombs designed to start fires or destroy sensitive equipment using materials such as napalm, thermite, chlorine trifluoride, or white phosphorus....

outside Judge Murtagh's home. The device detonated, but did little damage. After this incident, the Federal Bureau of Investigation

Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation is an agency of the United States Department of Justice that serves as both a federal criminal investigative body and an internal intelligence agency . The FBI has investigative jurisdiction over violations of more than 200 categories of federal crime...

began calling Jacobs one of the "most notorious" terrorists in the country. Robbins concluded the fire-bombs were unreliable, and turned toward using dynamite. The group began buying dynamite under false names from a variety of sources in the Northeast, and had soon acquired six cases of the explosive.

During the week of March 2, 1970, the collective moved into a townhouse at 18 West Eleventh Street in Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village, , , , .in New York often simply called "the Village", is a largely residential neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City. A large majority of the district is home to upper middle class families...

in New York City. The house belonged to James Platt Wilkerson, Cathy Wilkerson's father and a wealthy radio station owner. James Wilkerson was on vacation, and Cathy told her father she wanted to stay in the townhouse while she recovered from the flu. Reluctantly, James Wilkerson agreed. During the first few days in the townhouse, Robbins conceived a plan to bomb an officers' dance at Fort Dix in New Jersey

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Northeastern and Middle Atlantic regions of the United States. , its population was 8,791,894. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York, on the southeast and south by the Atlantic Ocean, on the west by Pennsylvania and on the southwest by Delaware...