Leó Szilárd

Encyclopedia

Leó Szilárd was an Austro-Hungarian physicist

and inventor who conceived the nuclear chain reaction

in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear reactor

with Enrico Fermi

, and in late 1939 wrote the letter for Albert Einstein

's signature that resulted in the Manhattan Project

that built the atomic bomb. He also conceived three revolutionary devices: the electron microscope

, the linear accelerator and the cyclotron

. Szilárd himself did not build all of these devices, or publish these ideas in scientific journals, and so their credit often went to others. As a result, Szilárd never received the Nobel Prize

, but two of his inventions did.

He was born in Budapest

in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and died in La Jolla, California.

Szilárd was born in 1898 to middle class parents in Budapest, Hungary

Szilárd was born in 1898 to middle class parents in Budapest, Hungary

as the son of a civil engineer

. His parents, both Jewish

, Louis Spitz and Thekla Vidor, raised Leó in the Városligeti fasor of Pest, Hungary. From 1908–1916 Leó attended Reáliskola high school in his home town. Showing an early interest in physics and a proficiency in mathematics, in 1916 took the Eötvös Prize, a national prize for mathematics.

He enrolled as an engineering student at Budapest Technical University

during 1916. The following year, he was drafted into the Austro-Hungarian Army

as an officer-candidate. Prior to his regiment being sent to the front lines, Szilárd fell ill with Spanish Influenza and he was returned home for hospitalization. Later he was informed that his regiment had been nearly annihilated in battle, so the sickness probably saved his life. He was discharged honorably at the end of the war.

During 1919 he resumed engineering studies at Budapest Technical University but soon decided to leave Hungary because of the chaotic political situation and the rising antisemitism under the Horthy

regime. Szilárd continued engineering studies at Technische Hochschule (Institute of Technology) in Berlin-Charlottenburg

. He soon changed to physics

there and took physics classes from Einstein

, Planck

, and Max von Laue

. His dissertation on thermodynamics

Über die thermodynamischen Schwankungserscheinungen (On The Manifestation of Thermodynamic Fluctuations) during 1922 was praised by Einstein

and awarded top honors. In 1923 he was awarded a doctorate in physics from Humboldt University of Berlin.

He was appointed as assistant to von Laue at the University of Berlin's Institute for Theoretical Physics during 1924. During 1927 he finished his habilitation

and became a Privatdozent

(private lecturer) in physics at University of Berlin. During his time in Berlin he was working on numerous technical inventions. For example, in 1928 he submitted a patent

application for the linear accelerator and, in 1929, he applied for a patent for the cyclotron

. During the 1926-1930 period, he worked with Einstein to develop a refrigerator

, notable because it had no moving parts. Szilárd's 1929 paper, Über die Entropieverminderung in einem thermodynamischen System bei Eingriffen intelligenter Wesen" (On the reduction of entropy in a thermodynamic system by the interference of an intelligent being) Z. Physik 53, 840-856, introduced the thought experiment now called Szilárd's engine and was important in the history of attempts to understand Maxwell's demon

.

Szilárd went to London in 1933 where he read an article in The Times

Szilárd went to London in 1933 where he read an article in The Times

summarizing a speech given by Ernest Rutherford

in which he rejected the possibility of using atomic energy for practical purposes. Rutherford's speech remarked specifically on the recent 1932 work of his students John Cockcroft

and Ernest Walton

in "splitting" lithium into alpha particles, by bombardment with protons from a particle accelerator they had constructed:

Although the atom had been split and energy released, nuclear fission

had not yet been discovered. However Szilárd was reportedly so annoyed at Rutherford's dismissal that on the same day the article about the Rutherford speech was printed in the morning paper, Szilárd conceived of the idea of nuclear chain reaction

(analogous to a chemical chain reaction

), using recently-discovered neutrons. The idea did not use the mechanism of nuclear fission

, which was not then known, but Szilárd realized that if neutrons could initiate any sort of energy-producting nuclear reaction, such as the one that had occurred in lithium, and could be produced themselves by the same reaction, energy might be obtained with little input, since the reaction would be self-sustaining. The following year he filed for a patent

on the concept of the neutron-induced nuclear chain reaction. Richard Rhodes described Szilárd's moment of inspiration:

Szilárd first attempted to create a nuclear chain reaction using beryllium

and indium

, but these elements

did not produce a chain reaction. During 1936, he assigned the chain-reaction patent to the British Admiralty to ensure its secrecy . Szilárd also was the co-holder, with Nobel Laureate Enrico Fermi

, of the patent on the nuclear reactor

.

During 1938 Szilárd accepted an offer to conduct research at Columbia University

in Manhattan

, and moved to New York, and was soon joined by Fermi. After learning about the successful nuclear fission

experiment conducted during 1939 in Germany by Otto Hahn

, Fritz Strassmann

, Lise Meitner

, and Otto Robert Frisch

, Szilárd and Fermi concluded that uranium

would be the element capable of sustaining a chain reaction. Szilárd and Fermi conducted a simple experiment at Columbia and discovered significant neutron multiplication in uranium, proving that the chain reaction was possible and enabling nuclear weapons. Szilárd later described the event: "We turned the switch and saw the flashes. We watched them for a little while and then we switched everything off and went home." He understood the implications and consequences of this discovery, though. "That night, there was very little doubt in my mind that the world was headed for grief."

At around that time the Germans and others were in a race to produce a nuclear chain reaction. German attempts to control the chain reaction sought to do so using graphite

, but these attempts proved unsuccessful. Szilárd realized graphite was indeed perfect for controlling chain reactions, just as the Germans had determined, but that the German method of producing graphite used boron carbide

rods, and the minute amount of boron

impurities in the manufactured graphite was enough to stop the chain reaction. Szilárd had graphite manufacturers produce boron-free graphite. As a result, the first human-controlled chain reaction occurred on December 2, 1942.

Szilárd was directly responsible for the creation of the Manhattan Project

Szilárd was directly responsible for the creation of the Manhattan Project

. He drafted a confidential letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt

explaining the possibility of nuclear weapons, warning of Nazi work on such weapons

and encouraging the development of a program which could result in their creation. During August 1939 he approached his old friend and collaborator Albert Einstein

and convinced him to sign the letter, lending his fame to the proposal. The Einstein–Szilárd letter resulted in the establishment of research into nuclear fission by the U.S. government and ultimately to the creation of the Manhattan Project; FDR gave the letter to an aide, General Edwin M. "Pa" Watson with the instruction: "Pa, this requires action!" Later, Szilárd relocated to the University of Chicago

to continue work on the project. There, along with Fermi, he helped to construct the first "neutronic reactor", a uranium and graphite "atomic pile" in which the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was achieved, during 1942.

As the war continued, Szilárd became increasingly dismayed that scientists were losing control over their research to the military, and argued many times with General Leslie Groves

, military director of the project. His resentment towards the U.S. government was exacerbated by his failure to prevent the destructive use of the atomic bomb through having a test explosion that could be witnessed by Japanese observers who would then have the opportunity to surrender and spare lives.

Szilárd became a naturalized citizen of the United States during 1943.

's science fiction

novel The World Set Free

. This inspired him to be the first scientist to examine seriously the science of the creation of nuclear weapon

s.

As a scientist, he was the first person to conceive of a device that, using a nuclear chain reaction

as fuel, could be used as a bomb.

As a survivor of the political and economic devastation in Hungary

following World War I

, which had been eviscerated by the Treaty of Trianon

, Szilárd developed an enduring passion for the preservation of human life and freedom, especially freedom to communicate ideas.

He hoped that the U.S. government would not use nuclear weapons because of their potential for use against civilian populations. Szilárd hoped that the mere threat of such weapons would force Germany and/or Japan to surrender. He drafted the Szilárd petition

advocating demonstration of the atomic bomb. However with the European war concluded and the U.S. suffering many casualties in the Pacific Ocean region, the new U.S. President Harry Truman agreed with advisers and chose to use atomic bombs against Hiroshima and Nagasaki

over the protestations of Szilárd and other scientists.

. In February 1950 Szilárd proposed a cobalt bomb

, a new kind of nuclear weapon using cobalt

as a tamper, which he said might destroy all life on the planet. U.S. News & World Report

featured an interview with Szilárd in its August 15, 1960 issue, "President Truman Didn't Understand." He argued that "violence would not have been necessary if we had been willing to negotiate." During 1961 Szilárd published a book of short stories, The Voice of the Dolphins, in which he dealt with the moral and ethical issues raised by the Cold War

and his own role in the development of atomic weapons. The title story described an international biology research laboratory in Central Europe. This became reality after a meeting in 1962 with Victor F. Weisskopf

, James Watson

and John Kendrew

. When the European Molecular Biology Laboratory

was established, the library was named The Szilárd Library and the library stamp features dolphins. Szilárd married Gertrud Weiss in 1951. During 1960, Szilárd was diagnosed with bladder cancer

. He underwent cobalt therapy

at New York's

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Hospital using a cobalt 60 treatment regimen that he designed himself. He was familiar with the properties of this isotope from his work on the cobalt bomb

. A second round of treatment with an increased dose followed during 1962. The doctors tried to tell him that the increased radiation dose would kill him, but he said it wouldn't, and that anyway he would die without it. The higher dose did its job and his cancer never returned. This treatment became standard for many cancers and is still used, though linear accelerators are preferred, when available. During 1962, Szilárd was part of a group of scientists who founded the Council for a Livable World

. The Council's goal was to warn the public and Congress of the threat of nuclear war and encourage rational arms control and nuclear disarmament. He spent his last years as a fellow of the Salk Institute in San Diego alongside his old friend Jacob Bronowski

. During May 1964, Szilárd died in his sleep of a heart attack

at the age of sixty-six.

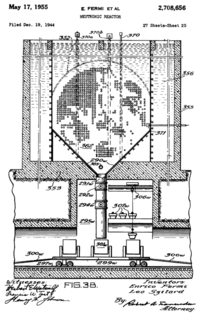

Patents—Neutronic reactor—E. Fermi, L. Szilárd, filed December 19, 1944, issued May 17, 1955—Einstein Refrigerator

—co-developed with Albert Einstein

filed in 1926, issued November 11, 1930

Physicist

A physicist is a scientist who studies or practices physics. Physicists study a wide range of physical phenomena in many branches of physics spanning all length scales: from sub-atomic particles of which all ordinary matter is made to the behavior of the material Universe as a whole...

and inventor who conceived the nuclear chain reaction

Nuclear chain reaction

A nuclear chain reaction occurs when one nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more nuclear reactions, thus leading to a self-propagating number of these reactions. The specific nuclear reaction may be the fission of heavy isotopes or the fusion of light isotopes...

in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear reactor

Nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device to initiate and control a sustained nuclear chain reaction. Most commonly they are used for generating electricity and for the propulsion of ships. Usually heat from nuclear fission is passed to a working fluid , which runs through turbines that power either ship's...

with Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi was an Italian-born, naturalized American physicist particularly known for his work on the development of the first nuclear reactor, Chicago Pile-1, and for his contributions to the development of quantum theory, nuclear and particle physics, and statistical mechanics...

, and in late 1939 wrote the letter for Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein was a German-born theoretical physicist who developed the theory of general relativity, effecting a revolution in physics. For this achievement, Einstein is often regarded as the father of modern physics and one of the most prolific intellects in human history...

's signature that resulted in the Manhattan Project

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program, led by the United States with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army...

that built the atomic bomb. He also conceived three revolutionary devices: the electron microscope

Electron microscope

An electron microscope is a type of microscope that uses a beam of electrons to illuminate the specimen and produce a magnified image. Electron microscopes have a greater resolving power than a light-powered optical microscope, because electrons have wavelengths about 100,000 times shorter than...

, the linear accelerator and the cyclotron

Cyclotron

In technology, a cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator. In physics, the cyclotron frequency or gyrofrequency is the frequency of a charged particle moving perpendicularly to the direction of a uniform magnetic field, i.e. a magnetic field of constant magnitude and direction...

. Szilárd himself did not build all of these devices, or publish these ideas in scientific journals, and so their credit often went to others. As a result, Szilárd never received the Nobel Prize

Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes are annual international awards bestowed by Scandinavian committees in recognition of cultural and scientific advances. The will of the Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, established the prizes in 1895...

, but two of his inventions did.

He was born in Budapest

Budapest

Budapest is the capital of Hungary. As the largest city of Hungary, it is the country's principal political, cultural, commercial, industrial, and transportation centre. In 2011, Budapest had 1,733,685 inhabitants, down from its 1989 peak of 2,113,645 due to suburbanization. The Budapest Commuter...

in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and died in La Jolla, California.

Early life

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

as the son of a civil engineer

Civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering; the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructures while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing infrastructures that have been neglected.Originally, a...

. His parents, both Jewish

Jews

The Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

, Louis Spitz and Thekla Vidor, raised Leó in the Városligeti fasor of Pest, Hungary. From 1908–1916 Leó attended Reáliskola high school in his home town. Showing an early interest in physics and a proficiency in mathematics, in 1916 took the Eötvös Prize, a national prize for mathematics.

He enrolled as an engineering student at Budapest Technical University

Budapest University of Technology and Economics

The Budapest University of Technology and Economics , in hungarian abbreviated as BME, English official abbreviation BUTE, is the most significant University of Technology in Hungary and is also one of the oldest Institutes of Technology in the world, having been founded in 1782.-History:BME is...

during 1916. The following year, he was drafted into the Austro-Hungarian Army

Austro-Hungarian Army

The Austro-Hungarian Army was the ground force of the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy from 1867 to 1918. It was composed of three parts: the joint army , the Austrian Landwehr , and the Hungarian Honvédség .In the wake of fighting between the...

as an officer-candidate. Prior to his regiment being sent to the front lines, Szilárd fell ill with Spanish Influenza and he was returned home for hospitalization. Later he was informed that his regiment had been nearly annihilated in battle, so the sickness probably saved his life. He was discharged honorably at the end of the war.

During 1919 he resumed engineering studies at Budapest Technical University but soon decided to leave Hungary because of the chaotic political situation and the rising antisemitism under the Horthy

Miklós Horthy

Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya was the Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary during the interwar years and throughout most of World War II, serving from 1 March 1920 to 15 October 1944. Horthy was styled "His Serene Highness the Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary" .Admiral Horthy was an officer of the...

regime. Szilárd continued engineering studies at Technische Hochschule (Institute of Technology) in Berlin-Charlottenburg

Technical University of Berlin

The Technische Universität Berlin is a research university located in Berlin, Germany. Translating the name into English is discouraged by the university, however paraphrasing as Berlin Institute of Technology is recommended by the university if necessary .The TU Berlin was founded...

. He soon changed to physics

Physics

Physics is a natural science that involves the study of matter and its motion through spacetime, along with related concepts such as energy and force. More broadly, it is the general analysis of nature, conducted in order to understand how the universe behaves.Physics is one of the oldest academic...

there and took physics classes from Einstein

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein was a German-born theoretical physicist who developed the theory of general relativity, effecting a revolution in physics. For this achievement, Einstein is often regarded as the father of modern physics and one of the most prolific intellects in human history...

, Planck

Max Planck

Max Karl Ernst Ludwig Planck, ForMemRS, was a German physicist who actualized the quantum physics, initiating a revolution in natural science and philosophy. He is regarded as the founder of the quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1918.-Life and career:Planck came...

, and Max von Laue

Max von Laue

Max Theodor Felix von Laue was a German physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1914 for his discovery of the diffraction of X-rays by crystals...

. His dissertation on thermodynamics

Thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a physical science that studies the effects on material bodies, and on radiation in regions of space, of transfer of heat and of work done on or by the bodies or radiation...

Über die thermodynamischen Schwankungserscheinungen (On The Manifestation of Thermodynamic Fluctuations) during 1922 was praised by Einstein

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein was a German-born theoretical physicist who developed the theory of general relativity, effecting a revolution in physics. For this achievement, Einstein is often regarded as the father of modern physics and one of the most prolific intellects in human history...

and awarded top honors. In 1923 he was awarded a doctorate in physics from Humboldt University of Berlin.

He was appointed as assistant to von Laue at the University of Berlin's Institute for Theoretical Physics during 1924. During 1927 he finished his habilitation

Habilitation

Habilitation is the highest academic qualification a scholar can achieve by his or her own pursuit in several European and Asian countries. Earned after obtaining a research doctorate, such as a PhD, habilitation requires the candidate to write a professorial thesis based on independent...

and became a Privatdozent

Privatdozent

Privatdozent or Private lecturer is a title conferred in some European university systems, especially in German-speaking countries, for someone who pursues an academic career and holds all formal qualifications to become a tenured university professor...

(private lecturer) in physics at University of Berlin. During his time in Berlin he was working on numerous technical inventions. For example, in 1928 he submitted a patent

Patent

A patent is a form of intellectual property. It consists of a set of exclusive rights granted by a sovereign state to an inventor or their assignee for a limited period of time in exchange for the public disclosure of an invention....

application for the linear accelerator and, in 1929, he applied for a patent for the cyclotron

Cyclotron

In technology, a cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator. In physics, the cyclotron frequency or gyrofrequency is the frequency of a charged particle moving perpendicularly to the direction of a uniform magnetic field, i.e. a magnetic field of constant magnitude and direction...

. During the 1926-1930 period, he worked with Einstein to develop a refrigerator

Einstein refrigerator

The Einstein-Szilard or Einstein refrigerator is an absorption refrigerator which has no moving parts, operates at constant pressure, and requires only a heat source to operate...

, notable because it had no moving parts. Szilárd's 1929 paper, Über die Entropieverminderung in einem thermodynamischen System bei Eingriffen intelligenter Wesen" (On the reduction of entropy in a thermodynamic system by the interference of an intelligent being) Z. Physik 53, 840-856, introduced the thought experiment now called Szilárd's engine and was important in the history of attempts to understand Maxwell's demon

Maxwell's demon

In the philosophy of thermal and statistical physics, Maxwell's demon is a thought experiment created by the Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell to "show that the Second Law of Thermodynamics has only a statistical certainty." It demonstrates Maxwell's point by hypothetically describing how to...

.

Developing the idea of the nuclear chain reaction

The Times

The Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

summarizing a speech given by Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson OM, FRS was a New Zealand-born British chemist and physicist who became known as the father of nuclear physics...

in which he rejected the possibility of using atomic energy for practical purposes. Rutherford's speech remarked specifically on the recent 1932 work of his students John Cockcroft

John Cockcroft

Sir John Douglas Cockcroft OM KCB CBE FRS was a British physicist. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physics for splitting the atomic nucleus with Ernest Walton, and was instrumental in the development of nuclear power....

and Ernest Walton

Ernest Walton

Ernest Thomas Sinton Walton was an Irish physicist and Nobel laureate for his work with John Cockcroft with "atom-smashing" experiments done at Cambridge University in the early 1930s, and so became the first person in history to artificially split the atom, thus ushering the nuclear age...

in "splitting" lithium into alpha particles, by bombardment with protons from a particle accelerator they had constructed:

- We might in these processes obtain very much more energy than the proton supplied, but on the average we could not expect to obtain energy in this way. It was a very poor and inefficient way of producing energy, and anyone who looked for a source of power in the transformation of the atoms was talking moonshine. But the subject was scientifically interesting because it gave insight into the atoms.

Although the atom had been split and energy released, nuclear fission

Nuclear fission

In nuclear physics and nuclear chemistry, nuclear fission is a nuclear reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into smaller parts , often producing free neutrons and photons , and releasing a tremendous amount of energy...

had not yet been discovered. However Szilárd was reportedly so annoyed at Rutherford's dismissal that on the same day the article about the Rutherford speech was printed in the morning paper, Szilárd conceived of the idea of nuclear chain reaction

Nuclear chain reaction

A nuclear chain reaction occurs when one nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more nuclear reactions, thus leading to a self-propagating number of these reactions. The specific nuclear reaction may be the fission of heavy isotopes or the fusion of light isotopes...

(analogous to a chemical chain reaction

Chain reaction

A chain reaction is a sequence of reactions where a reactive product or by-product causes additional reactions to take place. In a chain reaction, positive feedback leads to a self-amplifying chain of events....

), using recently-discovered neutrons. The idea did not use the mechanism of nuclear fission

Nuclear fission

In nuclear physics and nuclear chemistry, nuclear fission is a nuclear reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into smaller parts , often producing free neutrons and photons , and releasing a tremendous amount of energy...

, which was not then known, but Szilárd realized that if neutrons could initiate any sort of energy-producting nuclear reaction, such as the one that had occurred in lithium, and could be produced themselves by the same reaction, energy might be obtained with little input, since the reaction would be self-sustaining. The following year he filed for a patent

Patent

A patent is a form of intellectual property. It consists of a set of exclusive rights granted by a sovereign state to an inventor or their assignee for a limited period of time in exchange for the public disclosure of an invention....

on the concept of the neutron-induced nuclear chain reaction. Richard Rhodes described Szilárd's moment of inspiration:

- In London, where Southampton RowSouthampton RowSouthampton Row is major thoroughfare running northwest-southeast in Bloomsbury, Camden, central London, England. The road is designated as part of the A4200.- Location :To the north, Southampton Row adjoins the southeast corner of Russell Square...

passes Russell SquareRussell SquareRussell Square is a large garden square in Bloomsbury, in the London Borough of Camden. It is near the University of London's main buildings and the British Museum. To the north is Woburn Place and to the south-east is Southampton Row...

, across from the British MuseumBritish MuseumThe British Museum is a museum of human history and culture in London. Its collections, which number more than seven million objects, are amongst the largest and most comprehensive in the world and originate from all continents, illustrating and documenting the story of human culture from its...

in Bloomsbury, Leo Szilárd waited irritably one gray Depression morning for the stoplight to change. A trace of rain had fallen during the night; Tuesday, September 12, 1933, dawned cool, humid and dull. Drizzling rain would begin again in early afternoon. When Szilárd told the story later he never mentioned his destination that morning. He may have had none; he often walked to think. In any case another destination intervened. The stoplight changed to green. Szilárd stepped off the curb. As he crossed the street time cracked open before him and he saw a way to the future, death into the world and all our woes, the shape of things to come.

Szilárd first attempted to create a nuclear chain reaction using beryllium

Beryllium

Beryllium is the chemical element with the symbol Be and atomic number 4. It is a divalent element which occurs naturally only in combination with other elements in minerals. Notable gemstones which contain beryllium include beryl and chrysoberyl...

and indium

Indium

Indium is a chemical element with the symbol In and atomic number 49. This rare, very soft, malleable and easily fusible post-transition metal is chemically similar to gallium and thallium, and shows the intermediate properties between these two...

, but these elements

Chemical element

A chemical element is a pure chemical substance consisting of one type of atom distinguished by its atomic number, which is the number of protons in its nucleus. Familiar examples of elements include carbon, oxygen, aluminum, iron, copper, gold, mercury, and lead.As of November 2011, 118 elements...

did not produce a chain reaction. During 1936, he assigned the chain-reaction patent to the British Admiralty to ensure its secrecy . Szilárd also was the co-holder, with Nobel Laureate Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi was an Italian-born, naturalized American physicist particularly known for his work on the development of the first nuclear reactor, Chicago Pile-1, and for his contributions to the development of quantum theory, nuclear and particle physics, and statistical mechanics...

, of the patent on the nuclear reactor

Nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device to initiate and control a sustained nuclear chain reaction. Most commonly they are used for generating electricity and for the propulsion of ships. Usually heat from nuclear fission is passed to a working fluid , which runs through turbines that power either ship's...

.

During 1938 Szilárd accepted an offer to conduct research at Columbia University

Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York is a private, Ivy League university in Manhattan, New York City. Columbia is the oldest institution of higher learning in the state of New York, the fifth oldest in the United States, and one of the country's nine Colonial Colleges founded before the...

in Manhattan

Manhattan

Manhattan is the oldest and the most densely populated of the five boroughs of New York City. Located primarily on the island of Manhattan at the mouth of the Hudson River, the boundaries of the borough are identical to those of New York County, an original county of the state of New York...

, and moved to New York, and was soon joined by Fermi. After learning about the successful nuclear fission

Nuclear fission

In nuclear physics and nuclear chemistry, nuclear fission is a nuclear reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into smaller parts , often producing free neutrons and photons , and releasing a tremendous amount of energy...

experiment conducted during 1939 in Germany by Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn FRS was a German chemist and Nobel laureate, a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry. He is regarded as "the father of nuclear chemistry". Hahn was a courageous opposer of Jewish persecution by the Nazis and after World War II he became a passionate campaigner...

, Fritz Strassmann

Fritz Strassmann

Friedrich Wilhelm "Fritz" Strassmann was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in 1938, identified barium in the residue after bombarding uranium with neutrons, which led to the interpretation of their results as being from nuclear fission...

, Lise Meitner

Lise Meitner

Lise Meitner FRS was an Austrian-born, later Swedish, physicist who worked on radioactivity and nuclear physics. Meitner was part of the team that discovered nuclear fission, an achievement for which her colleague Otto Hahn was awarded the Nobel Prize...

, and Otto Robert Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch , Austrian-British physicist. With his collaborator Rudolf Peierls he designed the first theoretical mechanism for the detonation of an atomic bomb in 1940.- Overview :...

, Szilárd and Fermi concluded that uranium

Uranium

Uranium is a silvery-white metallic chemical element in the actinide series of the periodic table, with atomic number 92. It is assigned the chemical symbol U. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons...

would be the element capable of sustaining a chain reaction. Szilárd and Fermi conducted a simple experiment at Columbia and discovered significant neutron multiplication in uranium, proving that the chain reaction was possible and enabling nuclear weapons. Szilárd later described the event: "We turned the switch and saw the flashes. We watched them for a little while and then we switched everything off and went home." He understood the implications and consequences of this discovery, though. "That night, there was very little doubt in my mind that the world was headed for grief."

At around that time the Germans and others were in a race to produce a nuclear chain reaction. German attempts to control the chain reaction sought to do so using graphite

Graphite

The mineral graphite is one of the allotropes of carbon. It was named by Abraham Gottlob Werner in 1789 from the Ancient Greek γράφω , "to draw/write", for its use in pencils, where it is commonly called lead . Unlike diamond , graphite is an electrical conductor, a semimetal...

, but these attempts proved unsuccessful. Szilárd realized graphite was indeed perfect for controlling chain reactions, just as the Germans had determined, but that the German method of producing graphite used boron carbide

Boron carbide

Boron carbide is an extremely hard boron–carbon ceramic material used in tank armor, bulletproof vests, and numerous industrial applications...

rods, and the minute amount of boron

Boron

Boron is the chemical element with atomic number 5 and the chemical symbol B. Boron is a metalloid. Because boron is not produced by stellar nucleosynthesis, it is a low-abundance element in both the solar system and the Earth's crust. However, boron is concentrated on Earth by the...

impurities in the manufactured graphite was enough to stop the chain reaction. Szilárd had graphite manufacturers produce boron-free graphite. As a result, the first human-controlled chain reaction occurred on December 2, 1942.

The Manhattan Project

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program, led by the United States with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army...

. He drafted a confidential letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

explaining the possibility of nuclear weapons, warning of Nazi work on such weapons

German nuclear energy project

The German nuclear energy project, , was an attempted clandestine scientific effort led by Germany to develop and produce the atomic weapons during the events involving the World War II...

and encouraging the development of a program which could result in their creation. During August 1939 he approached his old friend and collaborator Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein was a German-born theoretical physicist who developed the theory of general relativity, effecting a revolution in physics. For this achievement, Einstein is often regarded as the father of modern physics and one of the most prolific intellects in human history...

and convinced him to sign the letter, lending his fame to the proposal. The Einstein–Szilárd letter resulted in the establishment of research into nuclear fission by the U.S. government and ultimately to the creation of the Manhattan Project; FDR gave the letter to an aide, General Edwin M. "Pa" Watson with the instruction: "Pa, this requires action!" Later, Szilárd relocated to the University of Chicago

University of Chicago

The University of Chicago is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois, USA. It was founded by the American Baptist Education Society with a donation from oil magnate and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller and incorporated in 1890...

to continue work on the project. There, along with Fermi, he helped to construct the first "neutronic reactor", a uranium and graphite "atomic pile" in which the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was achieved, during 1942.

As the war continued, Szilárd became increasingly dismayed that scientists were losing control over their research to the military, and argued many times with General Leslie Groves

Leslie Groves

Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves, Jr. was a United States Army Corps of Engineers officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and directed the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb during World War II. As the son of a United States Army chaplain, Groves lived at a...

, military director of the project. His resentment towards the U.S. government was exacerbated by his failure to prevent the destructive use of the atomic bomb through having a test explosion that could be witnessed by Japanese observers who would then have the opportunity to surrender and spare lives.

Szilárd became a naturalized citizen of the United States during 1943.

Views on the use of nuclear weapons

During 1932, Szilárd had read about the fictional "atomic bombs" described in H. G. WellsH. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells was an English author, now best known for his work in the science fiction genre. He was also a prolific writer in many other genres, including contemporary novels, history, politics and social commentary, even writing text books and rules for war games...

's science fiction

Science fiction

Science fiction is a genre of fiction dealing with imaginary but more or less plausible content such as future settings, futuristic science and technology, space travel, aliens, and paranormal abilities...

novel The World Set Free

The World Set Free

The World Set Free is a novel published in 1914 by H. G. Wells. The book is considered to foretell nuclear weapons. It had appeared first in serialized form with a different ending as A Prophetic Trilogy, consisting of three books: A Trap to Catch the Sun, The Last War in the World and The World...

. This inspired him to be the first scientist to examine seriously the science of the creation of nuclear weapon

Nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission or a combination of fission and fusion. Both reactions release vast quantities of energy from relatively small amounts of matter. The first fission bomb test released the same amount...

s.

As a scientist, he was the first person to conceive of a device that, using a nuclear chain reaction

Nuclear chain reaction

A nuclear chain reaction occurs when one nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more nuclear reactions, thus leading to a self-propagating number of these reactions. The specific nuclear reaction may be the fission of heavy isotopes or the fusion of light isotopes...

as fuel, could be used as a bomb.

As a survivor of the political and economic devastation in Hungary

Kingdom of Hungary (1920–1946)

The Kingdom of Hungary also known as the Regency, existed from 1920 to 1946 and was a de facto country under Regent Miklós Horthy. Horthy officially represented the abdicated Hungarian monarchy of Charles IV, Apostolic King of Hungary...

following World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, which had been eviscerated by the Treaty of Trianon

Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon was the peace agreement signed in 1920, at the end of World War I, between the Allies of World War I and Hungary . The treaty greatly redefined and reduced Hungary's borders. From its borders before World War I, it lost 72% of its territory, which was reduced from to...

, Szilárd developed an enduring passion for the preservation of human life and freedom, especially freedom to communicate ideas.

He hoped that the U.S. government would not use nuclear weapons because of their potential for use against civilian populations. Szilárd hoped that the mere threat of such weapons would force Germany and/or Japan to surrender. He drafted the Szilárd petition

Szilárd petition

The Szilárd petition, drafted by scientist Leó Szilárd, was signed by 155 scientists working on the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago, Illinois. It was circulated in July 1945 and asked President Harry S. Truman to consider an observed...

advocating demonstration of the atomic bomb. However with the European war concluded and the U.S. suffering many casualties in the Pacific Ocean region, the new U.S. President Harry Truman agreed with advisers and chose to use atomic bombs against Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

During the final stages of World War II in 1945, the United States conducted two atomic bombings against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the first on August 6, 1945, and the second on August 9, 1945. These two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.For six months...

over the protestations of Szilárd and other scientists.

After the war

During 1947, Szilárd switched topics of study because of his horror of atomic weapons, changing from physics to molecular biology, working extensively with Aaron NovickAaron Novick

Aaron Novick was a member of the Manhattan Project.Novick completed his doctorate in physical organic chemistry at the University of Chicago. There he joined the project, and proceeded to Hanford, Washington, where he helped produce plutonium. He witnessed the Trinity experiment...

. In February 1950 Szilárd proposed a cobalt bomb

Cobalt bomb

A cobalt bomb is a theoretical type of "salted bomb": a nuclear weapon intended to contaminate an area by radioactive material, with a relatively small blast....

, a new kind of nuclear weapon using cobalt

Cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with symbol Co and atomic number 27. It is found naturally only in chemically combined form. The free element, produced by reductive smelting, is a hard, lustrous, silver-gray metal....

as a tamper, which he said might destroy all life on the planet. U.S. News & World Report

U.S. News & World Report

U.S. News & World Report is an American news magazine published from Washington, D.C. Along with Time and Newsweek it was for many years a leading news weekly, focusing more than its counterparts on political, economic, health and education stories...

featured an interview with Szilárd in its August 15, 1960 issue, "President Truman Didn't Understand." He argued that "violence would not have been necessary if we had been willing to negotiate." During 1961 Szilárd published a book of short stories, The Voice of the Dolphins, in which he dealt with the moral and ethical issues raised by the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

and his own role in the development of atomic weapons. The title story described an international biology research laboratory in Central Europe. This became reality after a meeting in 1962 with Victor F. Weisskopf

Victor Frederick Weisskopf

Victor Frederick Weisskopf was an Austrian-born Jewish American theoretical physicist. He did postdoctoral work with Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger, Wolfgang Pauli and Niels Bohr...

, James Watson

James D. Watson

James Dewey Watson is an American molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist, best known as one of the co-discoverers of the structure of DNA in 1953 with Francis Crick...

and John Kendrew

John Kendrew

Sir John Cowdery Kendrew, CBE, FRS was an English biochemist and crystallographer who shared the 1962 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Max Perutz; their group in the Cavendish Laboratory investigated the structure of heme-containing proteins.-Biography:He was born in Oxford, son of Wilford George...

. When the European Molecular Biology Laboratory

European Molecular Biology Laboratory

The European Molecular Biology Laboratory is a molecular biology research institution supported by 20 European countries and Australia as associate member state. EMBL was created in 1974 and is an intergovernmental organisation funded by public research money from its member states...

was established, the library was named The Szilárd Library and the library stamp features dolphins. Szilárd married Gertrud Weiss in 1951. During 1960, Szilárd was diagnosed with bladder cancer

Bladder cancer

Bladder cancer is any of several types of malignant growths of the urinary bladder. It is a disease in which abnormal cells multiply without control in the bladder. The bladder is a hollow, muscular organ that stores urine; it is located in the pelvis...

. He underwent cobalt therapy

Cobalt therapy

Cobalt therapy or cobalt-60 therapy is the medical use of gamma rays from cobalt-60 radioisotopes to treat conditions such as cancer.Because the cobalt machines were expensive and required specialist support they were often housed in cobalt units.In 1961 cobalt therapy was expected to replace X-ray...

at New York's

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Hospital using a cobalt 60 treatment regimen that he designed himself. He was familiar with the properties of this isotope from his work on the cobalt bomb

Cobalt bomb

A cobalt bomb is a theoretical type of "salted bomb": a nuclear weapon intended to contaminate an area by radioactive material, with a relatively small blast....

. A second round of treatment with an increased dose followed during 1962. The doctors tried to tell him that the increased radiation dose would kill him, but he said it wouldn't, and that anyway he would die without it. The higher dose did its job and his cancer never returned. This treatment became standard for many cancers and is still used, though linear accelerators are preferred, when available. During 1962, Szilárd was part of a group of scientists who founded the Council for a Livable World

Council for a Livable World

Council for a Livable World is a Washington, D.C.-based non-profit, advocacy organization dedicated to eliminating the U.S. arsenal of nuclear weapons...

. The Council's goal was to warn the public and Congress of the threat of nuclear war and encourage rational arms control and nuclear disarmament. He spent his last years as a fellow of the Salk Institute in San Diego alongside his old friend Jacob Bronowski

Jacob Bronowski

Jacob Bronowski was a Polish-Jewish British mathematician, biologist, historian of science, theatre author, poet and inventor...

. During May 1964, Szilárd died in his sleep of a heart attack

Myocardial infarction

Myocardial infarction or acute myocardial infarction , commonly known as a heart attack, results from the interruption of blood supply to a part of the heart, causing heart cells to die...

at the age of sixty-six.

Honors

- American Academy of Arts and SciencesAmerican Academy of Arts and SciencesThe American Academy of Arts and Sciences is an independent policy research center that conducts multidisciplinary studies of complex and emerging problems. The Academy’s elected members are leaders in the academic disciplines, the arts, business, and public affairs.James Bowdoin, John Adams, and...

1954 - American Physical SocietyAmerican Physical SocietyThe American Physical Society is the world's second largest organization of physicists, behind the Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft. The Society publishes more than a dozen scientific journals, including the world renowned Physical Review and Physical Review Letters, and organizes more than 20...

- Atoms for Peace AwardAtoms for Peace AwardThe Atoms for Peace Award was established in 1955 through a grant of $1,000,000 by the Ford Motor Company Fund. An independent nonprofit corporation was set up to administer the award for the development or application of peaceful nuclear technology. It was created in response to U.S. President...

1959 - National Inventors Hall of FameNational Inventors Hall of FameThe National Inventors Hall of Fame is a not-for-profit organization dedicated to recognizing, honoring and encouraging invention and creativity through the administration of its programs. The Hall of Fame honors the men and women responsible for the great technological advances that make human,...

- Humanist of the YearAmerican Humanist AssociationThe American Humanist Association is an educational organization in the United States that advances Humanism. "Humanism is a progressive philosophy of life that, without theism and other supernatural beliefs, affirms our ability and responsibility to lead ethical lives of personal fulfillment that...

1960

- The crater SzilárdSzilard (crater)Szilard is a damaged lunar crater that lies to the east-northeast of the crater Richardson. It is named after Leo Szilard, the scientist who theorised nuclear chain reactions and famously worked on the atomic bomb during WWII. About a half-crater-diameter to the northwest is the large walled plain...

(34.0°N, 105.7°E, 122 km dia.) on the far side of the Moon is named after him.

External links

Information- Leo Szilárd Online—an "Internet Historic Site" (first created March 30, 1995) maintained by Gene Dannen

- Leo Szilárd's page at atomicarchive.com

- Einstein's Letter to President Roosevelt—1939

- Annotated bibliography for Leo Szilárd from the Alsos Digital Library

- Szilárd biography at Hungary.hu

- Council for a Livable World

- The Szilárd Library at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory

- Szilárd lecture on war

- Szilárd's math genealogy

Patents—Neutronic reactor—E. Fermi, L. Szilárd, filed December 19, 1944, issued May 17, 1955—Einstein Refrigerator

Einstein refrigerator

The Einstein-Szilard or Einstein refrigerator is an absorption refrigerator which has no moving parts, operates at constant pressure, and requires only a heat source to operate...

—co-developed with Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein was a German-born theoretical physicist who developed the theory of general relativity, effecting a revolution in physics. For this achievement, Einstein is often regarded as the father of modern physics and one of the most prolific intellects in human history...

filed in 1926, issued November 11, 1930