Lollardy

Encyclopedia

English Reformation

The English Reformation was the series of events in 16th-century England by which the Church of England broke away from the authority of the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church....

. The term "Lollard" refers to the followers of John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe was an English Scholastic philosopher, theologian, lay preacher, translator, reformer and university teacher who was known as an early dissident in the Roman Catholic Church during the 14th century. His followers were known as Lollards, a somewhat rebellious movement, which preached...

, a prominent theologian

Theology

Theology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

who was dismissed from the University of Oxford

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a university located in Oxford, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest surviving university in the world and the oldest in the English-speaking world. Although its exact date of foundation is unclear, there is evidence of teaching as far back as 1096...

in 1381 for criticism of the Church, especially his doctrine on the Eucharist

Eucharist

The Eucharist , also called Holy Communion, the Sacrament of the Altar, the Blessed Sacrament, the Lord's Supper, and other names, is a Christian sacrament or ordinance...

. Its demands were primarily for reform of Western Christianity

Western Christianity

Western Christianity is a term used to include the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church and groups historically derivative thereof, including the churches of the Anglican and Protestant traditions, which share common attributes that can be traced back to their medieval heritage...

.

Doctrine

Lollardy taught the concept of the "Church of the Saved," that there was an invisible true ChurchInvisible church

The invisible church or church invisible is a theological concept of an "invisible" body of the elect who are known only to God, in contrast to the "visible church"—that is, the institutional body on earth which preaches the gospel and administers the sacraments...

which was the community of the faithful, which overlapped with, but was not the same as, the visible Catholic Church

Church visible

Church visible is a term of Christian theology and ecclesiology referring to the visible community of Christian believers on Earth, as opposed to the Church invisible or Church triumphant, constituted by the fellowship of saints and the company of the elect.In ecclesiology, the Church visible has...

. It advocated apostolic poverty

Apostolic poverty

Apostolic poverty is a doctrine professed in the thirteenth century by the newly formed religious orders, known as the mendicant orders, in direct response to calls for reform in the Roman Catholic Church...

and taxation of Church properties. Other doctrines include consubstantiation

Consubstantiation

Consubstantiation is a theological doctrine that attempts to describe the nature of the Christian Eucharist in concrete metaphysical terms. It holds that during the sacrament, the fundamental "substance" of the body and blood of Christ are present alongside the substance of the bread and wine,...

instead of transubstantiation

Transubstantiation

In Roman Catholic theology, transubstantiation means the change, in the Eucharist, of the substance of wheat bread and grape wine into the substance of the Body and Blood, respectively, of Jesus, while all that is accessible to the senses remains as before.The Eastern Orthodox...

, although some of its followers went further. A Lollard blacksmith

Blacksmith

A blacksmith is a person who creates objects from wrought iron or steel by forging the metal; that is, by using tools to hammer, bend, and cut...

in Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire is a county in the east of England. It borders Norfolk to the south east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south west, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire to the west, South Yorkshire to the north west, and the East Riding of Yorkshire to the north. It also borders...

declared that he could make "as good a sacrament between ii yrons as the prest doth upon his auter (altar)".

Etymology

Lollard, Lollardi or Loller was the popular derogatory nickname given to those without an academic background, educated if at all only in English, who were reputed to follow the teachings of John Wycliffe in particular, and were certainly considerably energized by the translation of the Bible into the English language. By the mid-15th century the term lollard had come to mean a hereticHeretic

A heretic is a person who commits heresy.In literature:* Heretic, an autobiography of Peter Cameron* Heretic , the third volume in The Grail Quest series by Bernard CornwellIn music:...

in general. The alternative, "Wycliffite", is generally accepted to be a more neutral term covering those of similar opinions, but having an academic background.

The term is said to have been coined by the Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish was a term used primarily in the 19th and early 20th centuries to identify a privileged social class in Ireland, whose members were the descendants and successors of the Protestant Ascendancy, mostly belonging to the Church of Ireland, which was the established church of Ireland until...

cleric, Henry Crumpe

Henry Crumpe

Henry Crumpe, Anglo-Irish cleric, fl. 1380-1401.Henry Crumpe was an Oxford-based cleric from Ireland. He wrote sermons against John Wycliffe's views on dominion, though he was later condemned by the church as his views on the sacrament were deemed too close to Wycliffe.He is credited with terming...

, but its origin is uncertain. The Oxford English Dictionary has no doubt:

- from "M[iddle]

[ DutchDutch languageDutch is a West Germanic language and the native language of the majority of the population of the Netherlands, Belgium, and Suriname, the three member states of the Dutch Language Union. Most speakers live in the European Union, where it is a first language for about 23 million and a second...] lollaerd, lit. 'mumbler, mutterer', f[rom] lollen to mutter, mumble". - Three other possibilities for the derivation of Lollard have been suggested:

- the LatinLatinLatin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

name lolium (Common Vetch or tares, as a noxious weed mingled with the good Catholic wheat); - after the FranciscanFranciscanMost Franciscans are members of Roman Catholic religious orders founded by Saint Francis of Assisi. Besides Roman Catholic communities, there are also Old Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, ecumenical and Non-denominational Franciscan communities....

, Lolhard, who converted to the Waldensian way, becoming eminent as a preacher in GuienneAquitaineAquitaine , archaic Guyenne/Guienne , is one of the 27 regions of France, in the south-western part of metropolitan France, along the Atlantic Ocean and the Pyrenees mountain range on the border with Spain. It comprises the 5 departments of Dordogne, :Lot et Garonne, :Pyrénées-Atlantiques, Landes...

. That part of FranceFranceThe French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

was then under English domination, influencing lay English piety. He was burned at CologneCologneCologne is Germany's fourth-largest city , and is the largest city both in the Germany Federal State of North Rhine-Westphalia and within the Rhine-Ruhr Metropolitan Area, one of the major European metropolitan areas with more than ten million inhabitants.Cologne is located on both sides of the...

in the 1370s; - the Middle EnglishMiddle EnglishMiddle English is the stage in the history of the English language during the High and Late Middle Ages, or roughly during the four centuries between the late 11th and the late 15th century....

loller (akin to modern, albeit semi-archaic, verb loll), "a lazy vagabond, an idler, a fraudulent beggar"; but this word is not recorded in this sense before 1582. It is recorded as an alternative spelling of Lollard.

- the Latin

The Dutch derivation is the most likely. It appears to be a derisive expression applied to various people perceived as heretics — first the Franciscan

Franciscan

Most Franciscans are members of Roman Catholic religious orders founded by Saint Francis of Assisi. Besides Roman Catholic communities, there are also Old Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, ecumenical and Non-denominational Franciscan communities....

s and later the followers of Wycliffe. Originally the word was a colloquial name for a group of the harmless buriers of the dead during the Black Death

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

, in the 14th century, known as Alexians

Alexians

The Alexians, Alexian Brothers or Cellites are a Catholic religious institute or congregation specifically devoted to caring for the sick which has its origin in Europe at the time of the Black Death...

, Alexian Brothers or Cellites. These were known colloquially as lollebroeders (Middle Dutch

Dutch language

Dutch is a West Germanic language and the native language of the majority of the population of the Netherlands, Belgium, and Suriname, the three member states of the Dutch Language Union. Most speakers live in the European Union, where it is a first language for about 23 million and a second...

), 'mumbling brothers', or "Lollhorden", from Old , meaning "to sing softly," from their chants for the dead. The modern Dutch word is lullen, meaning to babble, to talk nonsense.

The derivation from the Latin lolium (tares) may be an interesting alternative. Scholarly etymology

Etymology

Etymology is the study of the history of words, their origins, and how their form and meaning have changed over time.For languages with a long written history, etymologists make use of texts in these languages and texts about the languages to gather knowledge about how words were used during...

, however, can show no proof of such a speculation.

Beliefs

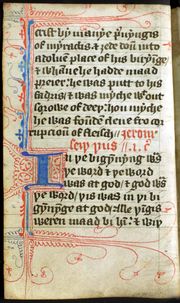

Believing the Catholic Church to be corrupted in many ways, the Lollards looked to Scripture as the basis for their religious ideas. To provide an authority for religion outside of the Church, Lollards began the movement towards a translation of the Bible into the vernacular

Vernacular

A vernacular is the native language or native dialect of a specific population, as opposed to a language of wider communication that is not native to the population, such as a national language or lingua franca.- Etymology :The term is not a recent one...

which enabled those literate in English to read the Bible. Wycliffe himself translated many passages before his death in 1384.

One group of Lollards petitioned Parliament with The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards

The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards

The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards is a Middle English religious text containing statements by followers of the English medieval sect, the Lollards, followers of John Wycliffe. The Conclusions were written in 1395...

by posting them on the doors of Westminster Hall in February 1395. While by no means a central authority of the Lollards, the Twelve Conclusions reveal certain basic Lollard ideas. The first Conclusion rejects the acquisition of temporal wealth by Church leaders as accumulating wealth leads them away from religious concerns and toward greed. The fourth Conclusion deals with the Lollard view that the Sacrament

Sacrament

A sacrament is a sacred rite recognized as of particular importance and significance. There are various views on the existence and meaning of such rites.-General definitions and terms:...

of Eucharist is a contradictory topic that is not clearly defined in the Bible. Whether the bread remains bread or becomes the literal body of Christ is not specified uniformly in the gospels. The sixth Conclusion states that officials of the Church should not concern themselves with secular matters when they hold a position of power within the Church because this constitutes a conflict of interest between matters of the spirit and matters of the State. The eighth Conclusion points out the ludicrousness, in the minds of Lollards, of the reverence that is directed toward images in the Church. As Anne Hudson states in her Reformation Ideology, "if the cross of Christ, the nails, spear, and crown of thorns are to be honoured, then why not honour Judas's lips, if only they could be found?" (306).

The Lollards stated that the Catholic Church had been corrupted by temporal matters and that its claim to be the true church was not justified by its heredity. Part of this corruption involved prayers for the dead and chantries

Chantry

Chantry is the English term for a fund established to pay for a priest to celebrate sung Masses for a specified purpose, generally for the soul of the deceased donor. Chantries were endowed with lands given by donors, the income from which maintained the chantry priest...

. These were seen as corrupt since they distracted priests from other work and that all should be prayed for equally. Lollards also had a tendency toward iconoclasm

Iconoclasm

Iconoclasm is the deliberate destruction of religious icons and other symbols or monuments, usually with religious or political motives. It is a frequent component of major political or religious changes...

. Expensive church artwork was seen as an excess; they believed effort should be placed on helping the needy and preaching rather than working on expensive decorations. Icons were also seen as dangerous since many seemed to be worshiping the icons more than God.

Believing in a lay priesthood

Priesthood of all believers

The universal priesthood or the priesthood of all believers, as it would come to be known in the present day, is a Christian doctrine believed to be derived from several passages of the New Testament...

, the Lollards challenged the Church’s authority to invest or deny the divine authority to make a man a priest. Denying any special status to the priesthood, Lollards thought confession

Confession

This article is for the religious practice of confessing one's sins.Confession is the acknowledgment of sin or wrongs...

to a priest was unnecessary since according to them priests did not have the ability to forgive sins. Lollards challenged the practice of clerical celibacy

Clerical celibacy

Clerical celibacy is the discipline by which some or all members of the clergy in certain religions are required to be unmarried. Since these religions consider deliberate sexual thoughts, feelings, and behavior outside of marriage to be sinful, clerical celibacy also requires abstension from these...

and believed priests should not hold government positions as such temporal matters would likely interfere with their spiritual mission.

Believing that more attention should be given to the message of the scriptures rather than to ceremony and worship, the Lollards denounced the doctrines of the Church such as transubstantiation

Transubstantiation

In Roman Catholic theology, transubstantiation means the change, in the Eucharist, of the substance of wheat bread and grape wine into the substance of the Body and Blood, respectively, of Jesus, while all that is accessible to the senses remains as before.The Eastern Orthodox...

, exorcism, pilgrimages, and blessings, believing these led to an emphasis on Church ritual rather than the Bible.

The other Conclusions dealt with their opposition to capital punishment

Capital punishment

Capital punishment, the death penalty, or execution is the sentence of death upon a person by the state as a punishment for an offence. Crimes that can result in a death penalty are known as capital crimes or capital offences. The term capital originates from the Latin capitalis, literally...

, rejection of religious celibacy, and belief that members of the Clergy should be held accountable to civil laws. The Conclusions also rejected pilgrimages, ornamentation of churches, and religious images because these were said to take away from the true nature of worship: focus on God. Also denounced in the Conclusions were war, violence, and abortion.

Outside of the Twelve Conclusions, Lollards held many diverse opinions. Their scriptural focus led them to refuse the taking of oaths. They also held a belief in millenarianism

Millenarianism

Millenarianism is the belief by a religious, social, or political group or movement in a coming major transformation of society, after which all things will be changed, based on a one-thousand-year cycle. The term is more generically used to refer to any belief centered around 1000 year intervals...

. Some criticized the Church for not focusing enough on Revelation

Revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing, through active or passive communication with a supernatural or a divine entity...

. Many believed their times were approaching the end of days

End of days

End of days may refer to:* End of Days , a religious concept* End of Days , a 1999 horror film* "End of Days" , a 2003 television episode* "End of Days" , a 2007 television episode...

. Some Lollard writings denounced the Pope as the Antichrist

Antichrist

The term or title antichrist, in Christian theology, refers to a leader who fulfills Biblical prophecies concerning an adversary of Christ, while resembling him in a deceptive manner...

. Generally, Lollards did not believe any particular Pope was the antichrist. However, they believed the office of the Pope embodied the prophecy of the Antichrist.

History

Christian heresy

Christian heresy refers to non-orthodox practices and beliefs that were deemed to be heretical by one or more of the Christian churches. In Western Christianity, the term "heresy" most commonly refers to those beliefs which were declared to be anathema by the Catholic Church prior to the schism of...

, Wycliffe and the Lollards were sheltered by John of Gaunt and other anti-clerical nobility, who likely were interested in using Lollard-advocated clerical reform to acquire new sources of revenue from England’s monasteries. The University of Oxford

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a university located in Oxford, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest surviving university in the world and the oldest in the English-speaking world. Although its exact date of foundation is unclear, there is evidence of teaching as far back as 1096...

also protected Wycliffe and similar academics on the grounds of academic freedom and, initially, allowed such persons to retain their positions despite their controversial views. Lollards first faced serious persecution after the Peasants' Revolt

Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, Wat Tyler's Rebellion, or the Great Rising of 1381 was one of a number of popular revolts in late medieval Europe and is a major event in the history of England. Tyler's Rebellion was not only the most extreme and widespread insurrection in English history but also the...

in 1381. While Wycliffe and other Lollards opposed the revolt, one of the peasants’ leaders, John Ball

John Ball (priest)

John Ball was an English Lollard priest who took a prominent part in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. In that year, Ball gave a sermon in which he asked the rhetorical question, "When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?".-Biography:Little is known of Ball's early years. He lived in...

, preached Lollardy. The royalty and nobility then found Lollardy to be a threat not only to the Church, but to English society in general. The Lollards' small measure of protection evaporated. This change in status was also affected by the 1386 departure of John of Gaunt who left England to pursue the Castilian

Crown of Castile

The Crown of Castile was a medieval and modern state in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and parliaments of the kingdoms of Castile and León upon the accession of the then King Ferdinand III of Castile to the vacant Leonese throne...

.

A group of gentry active during the reign of Richard II

Richard II of England

Richard II was King of England, a member of the House of Plantagenet and the last of its main-line kings. He ruled from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. Richard was a son of Edward, the Black Prince, and was born during the reign of his grandfather, Edward III...

(1377-1399) were known as "Lollard Knights" either during or after their lives due to their acceptance of Wycliffe's claims. Henry Knighton

Henry Knighton

Henry Knighton was an Augustinian canon at the abbey of St. Mary of the Meadows, Leicester, England. He was a canon at the Abbey since at least 1363, when he was recorded as being present during a visit from the King.-The chronicle:He wrote a four-volume chronicle, first published in 1652,...

, in his Chronicle, identifies the principal Lollard Knights as Thomas Latimer, John Trussel, Lewis Clifford, John Peachey, Richard Storey, and Reginald Hilton. Thomas Walsingham

Thomas Walsingham

- Life :He was probably educated at St Albans Abbey at St Albans, Hertfordshire, and at Oxford.He became a monk at St Albans, where he appears to have passed the whole of his monastic life, excepting a period from 1394 to 1396 during which he was prior of Wymondham Abbey, Norfolk, England, another...

's Chronicle adds William Nevil and John Clanvowe to the list, and other potential members of this circle have been identified by their wills, which contain Lollard-inspired language about how their bodies are to be plainly buried and permitted to return to the soil whence they came. There is little indication that the Lollard Knights were specifically known as such during their lifetimes; they were men of discretion, and unlike Sir John Oldcastle

John Oldcastle

Sir John Oldcastle , English Lollard leader, was son of Sir Richard Oldcastle of Almeley in northwest Herefordshire and grandson of another Sir John Oldcastle....

years later, rarely gave any hint of open rebellion. However, they displayed a remarkable ability to retain important positions without falling victim to the various prosecutions of Wycliffe's followers occurring during their lifetimes.

Religious and secular authorities strongly opposed Lollardy. A primary opponent was Thomas Arundel

Thomas Arundel

Thomas Arundel was Archbishop of Canterbury in 1397 and from 1399 until his death, an outspoken opponent of the Lollards.-Family background:...

, Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

, assisted by bishops like Henry le Despenser of Norwich

Bishop of Norwich

The Bishop of Norwich is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Norwich in the Province of Canterbury.The diocese covers most of the County of Norfolk and part of Suffolk. The see is in the City of Norwich where the seat is located at the Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided...

, whom the chronicler Thomas Walsingham

Thomas Walsingham

- Life :He was probably educated at St Albans Abbey at St Albans, Hertfordshire, and at Oxford.He became a monk at St Albans, where he appears to have passed the whole of his monastic life, excepting a period from 1394 to 1396 during which he was prior of Wymondham Abbey, Norfolk, England, another...

praised for his zeal. King Henry IV

Henry IV of England

Henry IV was King of England and Lord of Ireland . He was the ninth King of England of the House of Plantagenet and also asserted his grandfather's claim to the title King of France. He was born at Bolingbroke Castle in Lincolnshire, hence his other name, Henry Bolingbroke...

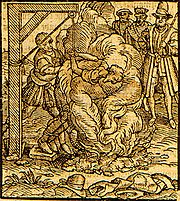

(despite being John of Gaunt's son) passed the De heretico comburendo

De heretico comburendo

The De heretico comburendo was a law passed by King Henry IV of England in 1401 punishing heretics with burning at the stake. This law was one of the strictest religious censorship statutes ever enacted in England....

in 1401, which did not specifically ban the Lollards, but prohibited translating or owning the Bible and authorised burning heretics at the stake

Execution by burning

Death by burning is death brought about by combustion. As a form of capital punishment, burning has a long history as a method in crimes such as treason, heresy, and witchcraft....

.

John Badby

John Badby , one of the early Lollard martyrs, was a tailor in the west Midlands, and was condemned by the Worcester diocesan court for his denial of transubstantiation....

, a layman and craftsman who refused to renounce his Lollardy. He was the first layman executed in England for the crime of heresy.

Sir John Oldcastle

John Oldcastle

Sir John Oldcastle , English Lollard leader, was son of Sir Richard Oldcastle of Almeley in northwest Herefordshire and grandson of another Sir John Oldcastle....

, a close friend of King Henry V

Henry V of England

Henry V was King of England from 1413 until his death at the age of 35 in 1422. He was the second monarch belonging to the House of Lancaster....

(and the basis for Falstaff

Falstaff

Sir John Falstaff is a fictional character who appears in three plays by William Shakespeare. In the two Henry IV plays, he is a companion to Prince Hal, the future King Henry V. A fat, vain, boastful, and cowardly knight, Falstaff leads the apparently wayward Prince Hal into trouble, and is...

in the Shakespearean history Henry IV

Henry IV, Part 1

Henry IV, Part 1 is a history play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written no later than 1597. It is the second play in Shakespeare's tetralogy dealing with the successive reigns of Richard II, Henry IV , and Henry V...

) was brought to trial in 1413 after evidence of his Lollard beliefs was uncovered. Oldcastle escaped from the Tower of London

Tower of London

Her Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress, more commonly known as the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, separated from the eastern edge of the City of London by the open space...

and organized an insurrection, which included an attempted kidnapping of the king. The rebellion failed, and Oldcastle was executed. Oldcastle's revolt made Lollardy seem even more threatening to the state, and persecution of Lollards became more severe. A variety of other martyr

Martyr

A martyr is somebody who suffers persecution and death for refusing to renounce, or accept, a belief or cause, usually religious.-Meaning:...

s for the Lollard cause were executed during the next century, including the Amersham Martyrs in the early 1500s and Thomas Harding

Thomas Harding

Thomas Harding was a sixteenth century English religious dissident who, whilst waiting to be burnt at the stake as a Lollard in 1532, was hit on the head by a piece of firewood which killed him instantly....

who died in 1532, one of the last Lollards to be persecuted. A gruesome reminder of this persecution is the 'Lollards Pit' in Thorpe Wood, Norfolk, where men are customablie burnt.

Lollards were effectively absorbed into Protestantism

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

during the English Reformation

English Reformation

The English Reformation was the series of events in 16th-century England by which the Church of England broke away from the authority of the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church....

, in which Lollardy played a role. Since Lollards had been underground for more than a hundred years, the extent of Lollardy and its ideas at the time of the Reformation is uncertain and a point of debate. Ancestors of Blanche Parry

Blanche Parry

Blanche Parry was a personal attendant of Queen Elizabeth I of England, Chief Gentlewoman of Queen Elizabeth’s most honourable Privy Chamber and Keeper of Her Majesty’s jewels.-Early life:...

(the closest person to Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

for 56 years) and of Lady Troy

Lady Troy

Blanche Herbert, Lady Troy, was the Lady Mistress in charge of the upbringing of Queen Elizabeth I, Edward VI and also of Queen Mary when she lived with the younger Tudor children...

(who raised Edward VI and Elizabeth I) had Lollard connections. However, many critics of the Reformation, including Thomas More

Thomas More

Sir Thomas More , also known by Catholics as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, social philosopher, author, statesman and noted Renaissance humanist. He was an important councillor to Henry VIII of England and, for three years toward the end of his life, Lord Chancellor...

, associated Protestants with Lollards. Leaders of the English Reformation

English Reformation

The English Reformation was the series of events in 16th-century England by which the Church of England broke away from the authority of the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church....

, including Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build a favourable case for Henry's divorce from Catherine of Aragon which resulted in the separation of the English Church from...

, referred to Lollardy as well, and Bishop Cuthbert of London

Cuthbert Tunstall

Cuthbert Tunstall was an English Scholastic, church leader, diplomat, administrator and royal adviser...

called Lutheranism the "foster-child" of the Wycliffite heresy. Scholars debate whether Protestants actually drew influence from Lollardy or whether they referred to it to create a sense of tradition. The extent of Lollardy in the general populace at this time is also unknown, but the prevalence of Protestant iconoclasm

Iconoclasm

Iconoclasm is the deliberate destruction of religious icons and other symbols or monuments, usually with religious or political motives. It is a frequent component of major political or religious changes...

in England suggests Lollard ideas may still have had some popular influence if Zwingli was not the source, as Lutherans did not advocate iconoclasm. The similarity between Lollards and later English Protestant groups such as the Baptists, Puritans, and Quakers

Religious Society of Friends

The Religious Society of Friends, or Friends Church, is a Christian movement which stresses the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers. Members are known as Friends, or popularly as Quakers. It is made of independent organisations, which have split from one another due to doctrinal differences...

also suggests some continuation of Lollard ideas through the Reformation.

Representations in art and literature

The Church used art as an anti-Lollard weapon. Lollards were represented as foxFox

Fox is a common name for many species of omnivorous mammals belonging to the Canidae family. Foxes are small to medium-sized canids , characterized by possessing a long narrow snout, and a bushy tail .Members of about 37 species are referred to as foxes, of which only 12 species actually belong to...

es dressed as monks or priests preaching to a flock of geese

Goose

The word goose is the English name for a group of waterfowl, belonging to the family Anatidae. This family also includes swans, most of which are larger than true geese, and ducks, which are smaller....

on misericord

Misericord

A misericord is a small wooden shelf on the underside of a folding seat in a church, installed to provide a degree of comfort for a person who has to stand during long periods of prayer.-Origins:...

s. These representations alluded to the story of the preaching fox found in popular Medieval literature such as The History of Reynard the Fox and The Shifts of Raynardine (the son of Raynard). The fox lured the geese closer and closer with its words until it was able to snatch a victim to devour. The moral of this story was that foolish people are seduced by false doctrines.

See also

- John WycliffeJohn WycliffeJohn Wycliffe was an English Scholastic philosopher, theologian, lay preacher, translator, reformer and university teacher who was known as an early dissident in the Roman Catholic Church during the 14th century. His followers were known as Lollards, a somewhat rebellious movement, which preached...

- Piers PlowmanPiers PlowmanPiers Plowman or Visio Willelmi de Petro Plowman is the title of a Middle English allegorical narrative poem by William Langland. It is written in unrhymed alliterative verse divided into sections called "passus"...

- Piers Plowman traditionPiers Plowman traditionThe Piers Plowman tradition is made up of about 14 different poetic and prose works from about the time of John Ball and the Peasants Revolt of 1381 through the reign of Elizabeth I and beyond. All the works feature one or more characters, typically Piers, from William Langland's poem Piers Plowman...

- WaldensiansWaldensiansWaldensians, Waldenses or Vaudois are names for a Christian movement of the later Middle Ages, descendants of which still exist in various regions, primarily in North-Western Italy. There is considerable uncertainty about the earlier history of the Waldenses because of a lack of extant source...

- William LanglandWilliam LanglandWilliam Langland is the conjectured author of the 14th-century English dream-vision Piers Plowman.- Life :The attribution of Piers to Langland rests principally on the evidence of a manuscript held at Trinity College, Dublin...

- Jan HusJan HusJan Hus , often referred to in English as John Hus or John Huss, was a Czech priest, philosopher, reformer, and master at Charles University in Prague...

- Thomas NetterThomas NetterThomas Netter was an English Scholastic theologian and controversialist. From his birthplace he is commonly called Thomas Waldensis.-Life:...

- Nicholas Love (monk)Nicholas Love (monk)Nicholas Love, also known as Nicholas Luff, was the first prior and fourth rector of the Carthusian house of Mount Grace Priory in Yorkshire . Love translated the "Meditationes Vitae Christi" Nicholas Love, also known as Nicholas Luff, (died c. 1424) was the first prior and fourth rector of the...

External links

- The Lollard Society — society dedicated to providing a forum for the study of the Lollards

- BBC radio 4 discussion from In Our TimeIn Our TimeIn Our Time may refer to:* In Our Time , a collection of short stories by Ernest Hemingway* In Our Time , a collection of illustrations by Tom Wolfe* In Our Time , a BBC discussion programme hosted by Melvyn Bragg...

. "John Wyclif and the Lollards". (45 mins)