Maori protest movement

Encyclopedia

The Māori protest movement is a broad indigenous rights

movement in New Zealand

. While this movement has existed since Europeans first colonised New Zealand its modern form emerged in the early 1970s and has focused on issues such as the Treaty of Waitangi

, Māori land rights, the Māori language

and culture

, and racism

. It has generally been allied with the left wing although it differs from the mainstream left in a number of ways. Most members of the movement have been Māori but it has attracted some support from Pākehā

New Zealanders and internationally, particularly from other indigenous peoples

. Notable successes of the movement include establishment of the Waitangi Tribunal

, the return of some Māori land, and the Māori language being made an official language of New Zealand. The movement is part of a broader Māori Renaissance

.

(New Zealand European) domination. From the 1840s to the 1870s various Māori iwi

(tribes) fought against Pākehā encroachment, in the New Zealand Land Wars

. They also used petitions, court cases, deputations to the British monarch and New Zealand and British governments, passive resistance and boycotts. Much of this resistance was based around religious movements such as Pai Marire

and Ringatu

. Prophet

s such as Rua Kenana and Te Whiti

are sometimes seen as early Māori activists. The Māori King movement was also an important focus of resistance, especially in the Taranaki and Waikato

regions. Some Māori also worked within Pākehā systems such as the New Zealand Parliament in order to resist land loss and cultural imperialism

.

From World War II

, but especially from the 1950s, Māori moved from rural areas to the cities in large numbers. Most Pākehā believed that New Zealand had ideal race relations and although relations were good compared to many other settler societies, the apparent harmony existed mostly because the mostly urban Pākehā and mostly rural Māori rarely came into contact. Māori urbanisation brought Pākehā prejudice and the gaps between Māori and Pākehā into the open. In addition, many Māori had difficulty coping with what was essentially an alien society. Some turned to alcohol or crime, and many felt lost and alone. Several new groups, most prominently the Māori Women's Welfare League

and the New Zealand Māori Council emerged to help urban Māori and provide a unified voice for Māori. These groups were conservative by later standards but did criticise the government on numerous occasions.

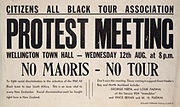

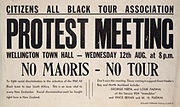

The first significant Māori involvement in conventional protest came during controversy over the exclusion of Māori players from the 1960 All Blacks

rugby tour of South Africa

. However the protests tended to be organised by Pākehā.

proposed to make Maori land more ‘economic’ by encouraging its transfer to a Pākehā system of land ownership. The Maori Affairs Amendment Act 1967, as it became, generally allowed greater interference in Māori landholding, and was widely seen amongst Maori as yet another Pākehā land grab. The plans were strongly opposed by virtually every Maori group and organisation. Despite this, the Act was passed with only minor modifications.

The Act is generally seen as the catalyst for the Maori protest movement, and the evidence certainly points to this. However the movement can also be seen as part of a wider civil rights movement

which emerged across the world in the 1960s.

New Zealand has a long history of sporting contact with South Africa

, especially through rugby union

. Until the 1970s this resulted in discrimination against Māori players, since the apartheid political system in South Africa for most of the twentieth century did not allow people of different races to play sport together, and therefore South African officials requested that Māori players not be included in sides which toured their country. Despite some of New Zealand's best players being Māori, this was agreed to, and Māori were excluded from tours of South Africa. Some Māori always objected to this, but it did not become a major issue until 1960, when there were several public protests at Māori exclusion from that year's tour. The protest group Halt All Racist Tours

was formed in 1969. Although this was an issue in which Māori were central, and Māori were involved in the protests, the anti-tour movement was dominated by Pākehā.

In 1973 a proposed Springbok

(South African rugby team) tour of New Zealand was cancelled. In 1976 the South African government relented and allowed a mixed-race All Black team to tour South Africa. However by this time international opinion had turned against any sporting contact with South Africa, and New Zealand faced significant international pressure to cut ties. Despite this, in 1981 the Springboks toured New Zealand, sparking mass protests and civil disobedience

. Although Pākehā continued to dominate the movement, Māori were prominent within it, and in Auckland

formed the patu

squad in order to remain autonomous within the wider movement.

During and after the Tour, many Māori protesters questioned Pākehā protesters' commitment to racial equality, accusing them of focussing on racism in other countries while ignoring it within New Zealand. The majority of Pākehā protesters were not heavily involved in protest after the Tour ended, but a significant minority, including several anti-Tour groups, turned their attention to New Zealand race issues, particularly Pākehā prejudice and the Treaty of Waitangi.

by a handful of Māori elders in 1968 in protest over the Māori Affairs Amendment Act. A small protest was also held at parliament, and was received by Labour

MP Whetu Tirikatene-Sullivan

. Although both were reported in the newspapers they made little impact. In 1971 the ceremonies were disrupted by the protest group Ngā Tamatoa

(The Young Warriors) who chanted and performed haka

during speeches, and attempted to destroy the flag. Protest has been a feature of Waitangi Day ever since.

(te reo Māori) and culture

. Both of these had been generally ignored by the education system and New Zealand society in general, and schoolchildren were actively discouraged from speaking Māori in school (the 1867 Native Schools Act decreed that English should be the only language used in the education of Māori children- this policy was later rigorously enforced ).This movement was led by Maori Mps who saw the advantages of Maori becomming fluent in a dominant world language. Until Māori became largely urbanised after World War II, this did not seriously damage the language since most Māori spoke it in their rural communities. Urbanisation produced a generation of Māori who mostly grew up in non-Māori environments and were therefore less exposed to the language. In addition, many parents felt that it was much more important for their children to be fluent in English and made no attempts to pass on the language. As a result, many leaders of Māori protest were not fluent in Māori and felt that this was a major cultural loss. In the face of official indifference and sometimes hostility, Nga Tamatoa and other groups initiated a number of schemes for the promotion of the language. These included Māori Language Day, which later became Māori Language Week

; a programme which trained fluent speakers as teachers; and kohanga reo

: Māori language pre-schools and later Maori kura or separate immersion schools at primary and secondary level. Later there were campaigns for a Māori share of the airwaves. These eventually resulted in the iwi radio stations and a Māori Television

channel, all of which actively promote the language. In 1987 Te Reo was made an official language

of New Zealand, with the passing of the Māori Language Act

. Activists also campaigned to change the names of landmarks such as mountains back to their original Māori names, and to end the mispronunciation of Māori words, especially by newsreaders and other broadcasters.

Many Māori cultural forms, such as carving, weaving and performing arts such as haka

had gone into decline in the nineteenth century. From the early twentieth century Apirana Ngata

and others had made efforts to revive them, for example setting up inter-tribal kapa haka

competitions and getting state funding for meeting houses. Māori activists continued this tradition, but their primary focus was on stopping the abuse of Māori cultural forms. The best known example of this was the 'haka party' incident. A group of University of Auckland

engineering students had for many years performed a parody haka and paddled an imaginary waka

around central Auckland as a capping stunt

. Repeated requests to end the performance were ignored and eventually a group of Māori assaulted the students. Although the activists' actions were widely condemned by Pākehā, they were defended in court by Māori elders and were convicted but the students' stunt was not performed again. Most recent Māori protest in this sphere has been directed against non-New Zealand groups and businesses who use the Māori language and cultural forms - sometimes copyrighting them - without permission or understanding. Since it is internationally known, the haka of the All Blacks

is particularly vulnerable to this treatment.

has always been a major focus of Māori protest. It is often used to argue for particular aims, such as return of unjustly taken land, and the promotion of the Māori language.

protests. In 1975 the Treaty was given some recognition with the Treaty of Waitangi Act

. This established the Waitangi Tribunal

, which was given the task to investigating contemporary breaches of the Treaty. However since it was not able to investigate historical breaches, was underfunded, and generally unsympathetic to claimants, most Māori were disappointed by the Tribunal.

. In some cases the land was purchased legitimately from willing Māori sellers, but in many cases the transfer was legally and/or morally dubious. The best known cause of Māori land loss is the confiscation

in the Waikato

and Taranaki regions following the New Zealand Land Wars

. Other causes included owners selling land without fully understanding the implications of the sale (especially in the early years of colonisation); groups selling land which did not belong to them; Pākehā traders enticing land owners into debt and then claiming the land as payment; the conducting of unrequested surveys which were then charged to the owners, and the unpaid bills from this used to justify taking the land; levying of unreasonable rates and confiscation following non-payment; the taking of land for public works

; and simple fraud. Upon losing land, most iwi quickly embarked on campaigns to regain it but these were largely unsuccessful. Some iwi received token payments from the government but continued to agitate for the return of the land or, failing that, adequate compensation.

The return of lost land was a major focus of Māori activists, and generally united the older, more conservative generation with the younger 'protest' generation. Some of the best-known episodes of Māori protest centred on land, including:

in Auckland

was originally part of a large area of land owned by Ngati Whatua

. Between 1840 and 1960 nearly all of this was lost, leaving Ngati Whatua with only the Point. In the 1970s the third National government

proposed taking the land and developing it. Bastion Point was subsequently occupied in a protest which lasted from January 1977 to May 1978. The protesters were removed by the army and police, but there continued to be conflict over the land. When the Waitangi Tribunal was given the power to investigate historical grievances, this the Orakei

claim covering the Bastion Point area was one of the first cases for investigation. The Tribunal found that Ngati Whatua had been unjustly deprived of their ancestral land hence Bastion Point was returned to their ownership with compensation paid to the tribe by the Crown.

. A group of protesters led by Eva Rickard

and assisted by Angeline Greensill

occupied the land and also used legal means to have the land returned, a goal which was eventually achieved.

, walked the length of the North Island

to Wellington

to protest against Māori land loss. Although the government at the time, the third Labour government

, had done more to address Māori grievances than nearly any prior government, protesters felt that much more needed to be done. Following the march, the protesters were divided over what to do next. Some, including Tame Iti

, remained in Wellington to occupy parliament grounds. A 1975 documentary from director Geoff Steven includes interviews with many of those on the march: Eva Rickard

, Tama Poata

and Whina Cooper

.

and removing a Colin McCahon painting (subsequently returned) from the Lake Waikaremoana

Visitor Centre. Rising protests at the Waitangi Day

celebrations led the government to move the official observance to Government House in Wellington. Many protests were generated in response to the government's proposal to limit the monetary value of Treaty settlements to one billion dollars over 10 years, the so-called fiscal envelope. A series of hui (meetings) graphically illustrated the breadth and depth of Maori rejection of such a limitation in advance of the extent of claims being fully known. As a result, much of the policy package, especially the fiscal cap, was dropped. These protests included occupations of Whanganui's Moutoa Gardens and the Takahue school in Northland (leading to its destruction by fire).

was established in the Ministry of Justice to develop government policy on historical claims. In 1995, the government developed the "Crown Proposals for the Settlement of Treaty of Waitangi Claims" to attempt to address the issues. A key element of the proposals was the creation of a "fiscal envelope" of $1 billion for the settlement of all historical claims, an effective limit on what the Crown would pay out in settlements. The Crown held a series of consultation hui

around the country, at which Māori vehemently rejected such a limitation in advance of the extent of claims being fully known. The concept of the fiscal envelope was subsequently dropped after the 1996 general election

. Opposition to the policy was coordinated by Te Kawau Maro an Auckland group who organised protests at the Government consultation Hui. Rising protests to the Fiscal Envelope at the Waitangi Day

celebrations led the government to move the official observance to Government House in Wellington. Despite universal rejection of the 'Fiscal Envelope', Waikato-Tainui negotiators, accepted the Government Deal which became known as the Waikato Tainui Raupatu Settlement. Notable opposition to this deal was led by Maori leader Eva Rickard

.

"We were forced to leave, and it shouldn't be lost on anybody that we upheld our dignity," protest leader Ken Mair

told a press conference in Whanganui May 18, 1995 following the end of the occupation." In no way were we going to allow the state the opportunity to put the handcuffs on us and lock us away."

The police were reported to have up to 1,000 reinforcements ready to evict the land occupants. Whanganuí Kaitoke prison had been gazetted as a "police jail" to enable its use as holding cells. The police eviction preparations were code-named "Operation Exodus".

A week earlier, on May 10, up to 70 police in riot gear had raided the land occupation in the middle of the night, claiming the protest had become a haven for "criminals and stolen property" and "drug users." Ten people were arrested on minor charges including "breach of the peace" and "assault." Throughout the occupation there has been a strict policy of no drugs or alcohol on the site.

Protest leaders denounced the raid as a dress rehearsal for their forced eviction and an attempt to provoke, intimidate, and discredit the land occupants. Throughout the 79-day occupation, the land protesters faced almost nightly harassment and racist abuse by the police.

The decision to end the Maori occupation of Moutoa Gardens was debated by participants at a three-hour meeting May 17, 1995. At 3:45 the next morning the occupants gathered and began dismantling tents and buildings and the surrounding fence. Bonfires burned across the site.

At 4:50 a.m., the same time they had entered the gardens 79 days earlier, the protesters began their march to a meeting place several miles away. Over the next few days, a team continued to dismantle the meeting house and other buildings that had been erected during the occupation.

"Every step of the way has been worthwhile as far as we are concerned," Niko Tangaroa told the May 18 press conference in Wanganui. "Pakaitore is our land. It will remain our land, and we will continue to assert that right irrespective of the courts."

The protest leaders vowed to continue their fight, including through further land occupations. "As long as the Crown [government] buries its head in the sand and pretends that issues of sovereignty and our land grievances are going to go away- we are going to stand up and fight for what is rightfully ours," Ken Mair

declared.

The 6 acres (24,281.2 m²) they claimed were part of 4500 acres (18.2 km²) purchased by the government in 1875, in a transaction the protesters, descendants of the original owners, regard as invalid. The school has been closed since the mid 1980s and used as an army training camp and for community activities since then.

Bill Perry, a spokesperson for the protesters, explained to reporters who visited the occupation April 22 in 1995 that the land they are claiming has been set aside in a government controlled Landbank together with other property in the region. This Landbank allegedly protects lands currently subject to claims under the Waitangi Tribunal from sale pending settlement of the claims.

The occupation ended with mass arrests and the burning of the school.

Protesters told reporters who visited the occupation April 29 that the land is part of 1200000 acres (4,856.2 km²) confiscated by the government 132 years ago from the Tainui tribe. It is now owned by Coalcorp, a private coal company that was previously state-owned. Most coal miners in New Zealand lost their jobs when the government-run coal industry was transformed into a state-owned corporation in 1987, prior to its privatization.

Those occupying the land are demanding its return to Ngati Whawhakia, the local Maori sub-tribe. The claim includes coal and mineral rights.

Robert Tukiri, chairman of Ngati Whawhakia Trust and spokesperson for the occupation said, "We have got our backs to the wall. There is a housing shortage. We need to have houses."

Tukiri opposed a NZ$170 million (NZ$1=US$0.67) deal between the government and the Tainui Maori Trust Board due to be signed May 22 as final settlement for the government's land seizures last century. The agreement will turn over 86000 acres (348 km²) of state-owned land to the trust board and NZ$65 million for further purchases of private land.

"The Tainui Maori Trust Board stands to become the biggest landlord around, while 80 percent of our tribe rents their homes," Tukiri commented.

In 2003 the Court of Appeal ruled that Māori could seek customary title to areas of the New Zealand foreshore and seabed

, overturning assumptions that such land automatically belonged to the Crown. The ruling alarmed many Pākehā, and the Labour government

proposed legislation removing the right to seek ownership of the foreshore and seabed. This angered many Māori who saw it as confiscation of land. Labour Party

MP Tariana Turia

was so incensed by the legislation that she eventually left the party and formed the Māori Party

. In May 2004 a hikoi

(march) from Northland to Wellington, modelled on the 1975 land march but in vehicles, was held, attracting thousands of participants. Despite this, the legislation was passed later that year.

. The group has held numerous campaigns highlighting the rights of the Tuhoe

people. The ideology of the group is based on self-government as a base principle of democracy and that Tuhoe has the democratic right to self-government. Tuhoe were not signatories of the Treaty of Waitangi, and have always maintained a right to uphold uniquely Tuhoe values, culture, language and identity within Tuhoe homelands.

(or greeting ceremony) which formed part of a Waitangi Tribunal

hearing, Tāme Iti fired a shotgun

into a New Zealand

flag in close proximity to a large number of people, which he explained was an attempt to recreate the 1860s East Cape War

: "We wanted them to feel the heat and smoke, and Tūhoe outrage and disgust at the way we have been treated for 200 years". The incident was filmed by television crews but initially ignored by police. The matter was however raised in parliament, one opposition MP

asking "why Tāme Iti can brandish a firearm and gloat about how he got away with threatening judges on the Waitangi Tribunal, without immediate arrest and prosecution".

New Zealand Police

subsequently charged Iti with discharging a firearm in a public place. His trial occurred in June 2006. Tāme Iti elected to give evidence in Māori (his native language), stating that he was following the Tūhoe custom of making noise with totara poles. Tūhoe Rangatira stated Iti had been disciplined by the tribe and protocol clarified to say discharge of a weapon in anger was always inappropriate (but stated that it was appropriate when honouring dead warriors, (in a manner culturally equivalent to the firing of a volley over a grave within Western cultures)). Judge Chris McGuire said "It was designed to intimidate unnecessarily and shock. It was a stunt, it was unlawful".

Judge McGuire convicted Iti on both charges and fined him. Iti attempted to sell the flag he shot on the TradeMe

auction site to pay the fine and his legal costs, but the sale - a violation of proceeds of crime legislation - was withdrawn.

Iti lodged an appeal, in which his lawyer, Annette Sykes

, argued that Crown Law did not stretch to the ceremonial area in front of a Marae's Wharenui. On April 4, 2007, the Court of Appeal of New Zealand

overturned his convictions for unlawfully possessing a firearm. While recognising that events occurred in "a unique setting", the court did not agree with Sykes' submission about Crown law. However Justices Hammond, O'Regan and Wilson found that his prosecutors failed to prove beyond reasonable doubt that Iti's actions caused "requisite harm", under Section 51 of the Arms Act. The Court of Appeal described Iti's protest as "a foolhardy enterprise" and warned him not to attempt anything similar again.

mountain range near the town of Ruatoki

in the eastern Bay of Plenty

.

About 300 police

, including members of the Armed Offenders

and anti-terror squads, were involved in the raids in which four guns

and 230 rounds of ammunition

were seized and 17 people arrested, all but one of them charged with firearms offences. According to police, the raids were a culmination of more than a year of surveillance that uncovered and monitored the training camps. Search warrants were executed under the Summary Proceedings Act to search for evidence relating to potential breaches of the Terrorism Suppression Act

and the Arms Act

.

On 29 October, police referred evidence gathered during the raids to the Solicitor-General

to consider whether charges should be laid under the Terrorism Suppression Act. Authorisation for prosecutions under the Act is given by the Attorney-General though he has delegated this responsibility to Solicitor-General David Collins. On 8 November the Solicitor-General declined to press charges under the Terrorism Suppression Act, because of inadequacies of the legislation. According to Prime Minister Helen Clark

, one of the reasons police tried to lay charges under anti-terror legislation was because they could not use telephone interception evidence in prosecutions under the Arms Act.

Activists that were arrested and raided are known supporters of Te Mana Motuhake o Tuhoe and came from diverse networks of environmental, anarchist and Maori activism.

, his nephews Rawiri Iti and Maraki Teepa, Maori anarchist Emily Bailey from Parihaka

along with her twin brothers Ira and Rongomai, Rangi Kemara of Ngati Maniapoto

, Vietnam war

veterans Tuhoe Francis Lambert and Moana Hemi Winitana also of Ngai Tuhoe, Radical youth

anarchist Omar Hamed. Others included Marama Mayrick, who faces five firearms charges; Other defendants include Trudi Paraha, Phillip Purewa, Valerie Morse, Urs Peter Signer and Tekaumarua Wharepouri Of the people arrested, at least 16 are facing firearms charges. Police also attempted to lay charges against 12 people under the Terrorism Suppression act but the Solicitor General declined to prosecute for charges under the act.

All charges against Rongomai Bailey were dropped in October 2008

and Māori Affairs Minister Pita Sharples

announced that the Maori Tino Rangatiratanga flag has been chosen to fly from the Auckland Harbour Bridge

and other official buildings (such as Premier House

) on Waitangi Day

. The announcement followed a Māori Party led promotion and series of hikoi

on which Māori flag should fly from the bridge and 1,200 submissions, with 80 per cent of participants in favour of Tino Rangatiratanga flag as the preferred Māori flag.

Key said the Māori flag would not replace the New Zealand flag but would fly alongside it to recognise the partnership the Crown and Māori entered into when signing the Treaty of Waitangi. "No changes are being made to the status of the New Zealand flag," Mr Key said.

Sharples said the Maori flag was a simple way to recognise the status of Māori as tangata whenua. "However, the New Zealand flag remains the symbol of our nation, and there is no intention to change this, nor to diminish the status of our national flag."

The Ministry of Culture and Heritage published guidelines describing the appropriate way to fly the Maori flag in relation to the New Zealand flag.

Indigenous rights

Indigenous rights are those rights that exist in recognition of the specific condition of the indigenous peoples. This includes not only the most basic human rights of physical survival and integrity, but also the preservation of their land, language, religion and other elements of cultural...

movement in New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

. While this movement has existed since Europeans first colonised New Zealand its modern form emerged in the early 1970s and has focused on issues such as the Treaty of Waitangi

Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi is a treaty first signed on 6 February 1840 by representatives of the British Crown and various Māori chiefs from the North Island of New Zealand....

, Māori land rights, the Māori language

Maori language

Māori or te reo Māori , commonly te reo , is the language of the indigenous population of New Zealand, the Māori. It has the status of an official language in New Zealand...

and culture

Maori culture

Māori culture is the culture of the Māori of New Zealand, an Eastern Polynesian people, and forms a distinctive part of New Zealand culture. Within the Māori community, and to a lesser extent throughout New Zealand as a whole, the word Māoritanga is often used as an approximate synonym for Māori...

, and racism

Racism

Racism is the belief that inherent different traits in human racial groups justify discrimination. In the modern English language, the term "racism" is used predominantly as a pejorative epithet. It is applied especially to the practice or advocacy of racial discrimination of a pernicious nature...

. It has generally been allied with the left wing although it differs from the mainstream left in a number of ways. Most members of the movement have been Māori but it has attracted some support from Pākehā

Pakeha

Pākehā is a Māori language word for New Zealanders who are "of European descent". They are mostly descended from British and to a lesser extent Irish settlers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, although some Pākehā have Dutch, Scandinavian, German, Yugoslav or other ancestry...

New Zealanders and internationally, particularly from other indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are ethnic groups that are defined as indigenous according to one of the various definitions of the term, there is no universally accepted definition but most of which carry connotations of being the "original inhabitants" of a territory....

. Notable successes of the movement include establishment of the Waitangi Tribunal

Waitangi Tribunal

The Waitangi Tribunal is a New Zealand permanent commission of inquiry established under the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975...

, the return of some Māori land, and the Māori language being made an official language of New Zealand. The movement is part of a broader Māori Renaissance

Maori Renaissance

The term Māori Renaissance refers to the revival in fortunes of the Māori of New Zealand in the latter half of the twentieth century. During this period, the perception of Māori went from being that of a dying race to being politically, culturally artistically and artistically ascendant.The...

.

Background

There is a long history of Māori resistance to PākehāPakeha

Pākehā is a Māori language word for New Zealanders who are "of European descent". They are mostly descended from British and to a lesser extent Irish settlers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, although some Pākehā have Dutch, Scandinavian, German, Yugoslav or other ancestry...

(New Zealand European) domination. From the 1840s to the 1870s various Māori iwi

Iwi

In New Zealand society, iwi form the largest everyday social units in Māori culture. The word iwi means "'peoples' or 'nations'. In "the work of European writers which treat iwi and hapū as parts of a hierarchical structure", it has been used to mean "tribe" , or confederation of tribes,...

(tribes) fought against Pākehā encroachment, in the New Zealand Land Wars

New Zealand land wars

The New Zealand Wars, sometimes called the Land Wars and also once called the Māori Wars, were a series of armed conflicts that took place in New Zealand between 1845 and 1872...

. They also used petitions, court cases, deputations to the British monarch and New Zealand and British governments, passive resistance and boycotts. Much of this resistance was based around religious movements such as Pai Marire

Pai Marire

The Pai Mārire movement was a syncretic Māori religion that flourished in New Zealand from about 1863 to 1874. Founded in Taranaki by the prophet Te Ua Haumene, it incorporated Biblical and Māori spiritual elements and promised its followers deliverance from Pākehā domination, providing a...

and Ringatu

Ringatu

The Ringatū church was founded in 1868 by Te Kooti Rikirangi. The symbol for the movement is an upraised hand, or "Ringa Tū" in Māori.Te Kooti was one of a number of Māori detained at the Chatham Islands without trial in relation to the East Coast disturbances of the 1860s...

. Prophet

Prophet

In religion, a prophet, from the Greek word προφήτης profitis meaning "foreteller", is an individual who is claimed to have been contacted by the supernatural or the divine, and serves as an intermediary with humanity, delivering this newfound knowledge from the supernatural entity to other people...

s such as Rua Kenana and Te Whiti

Te Whiti o Rongomai

Te Whiti o Rongomai III was a Māori spiritual leader and founder of the village of Parihaka, in New Zealand's Taranaki region.-Biography:...

are sometimes seen as early Māori activists. The Māori King movement was also an important focus of resistance, especially in the Taranaki and Waikato

Waikato

The Waikato Region is a local government region of the upper North Island of New Zealand. It covers the Waikato, Hauraki, Coromandel Peninsula, the northern King Country, much of the Taupo District, and parts of Rotorua District...

regions. Some Māori also worked within Pākehā systems such as the New Zealand Parliament in order to resist land loss and cultural imperialism

Cultural imperialism

Cultural imperialism is the domination of one culture over another. Cultural imperialism can take the form of a general attitude or an active, formal and deliberate policy, including military action. Economic or technological factors may also play a role...

.

From World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, but especially from the 1950s, Māori moved from rural areas to the cities in large numbers. Most Pākehā believed that New Zealand had ideal race relations and although relations were good compared to many other settler societies, the apparent harmony existed mostly because the mostly urban Pākehā and mostly rural Māori rarely came into contact. Māori urbanisation brought Pākehā prejudice and the gaps between Māori and Pākehā into the open. In addition, many Māori had difficulty coping with what was essentially an alien society. Some turned to alcohol or crime, and many felt lost and alone. Several new groups, most prominently the Māori Women's Welfare League

Māori Women's Welfare League

The Māori Women’s Welfare League or Te Rōpū Wāhine Māori Toko I te Ora is a New Zealand welfare organisation focusing on Māori women and children...

and the New Zealand Māori Council emerged to help urban Māori and provide a unified voice for Māori. These groups were conservative by later standards but did criticise the government on numerous occasions.

The first significant Māori involvement in conventional protest came during controversy over the exclusion of Māori players from the 1960 All Blacks

All Blacks

The New Zealand men's national rugby union team, known as the All Blacks, represent New Zealand in what is regarded as its national sport....

rugby tour of South Africa

South Africa

The Republic of South Africa is a country in southern Africa. Located at the southern tip of Africa, it is divided into nine provinces, with of coastline on the Atlantic and Indian oceans...

. However the protests tended to be organised by Pākehā.

The Māori Affairs Amendment Act

In the mid 1960s the National governmentSecond National Government of New Zealand

The Second National Government of New Zealand was the government of New Zealand from 1960 to 1972. It was a conservative government which sought mainly to preserve the economic prosperity and general stability of the early 1960s...

proposed to make Maori land more ‘economic’ by encouraging its transfer to a Pākehā system of land ownership. The Maori Affairs Amendment Act 1967, as it became, generally allowed greater interference in Māori landholding, and was widely seen amongst Maori as yet another Pākehā land grab. The plans were strongly opposed by virtually every Maori group and organisation. Despite this, the Act was passed with only minor modifications.

The Act is generally seen as the catalyst for the Maori protest movement, and the evidence certainly points to this. However the movement can also be seen as part of a wider civil rights movement

Civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a worldwide political movement for equality before the law occurring between approximately 1950 and 1980. In many situations it took the form of campaigns of civil resistance aimed at achieving change by nonviolent forms of resistance. In some situations it was...

which emerged across the world in the 1960s.

Sporting contact with South Africa

New Zealand has a long history of sporting contact with South Africa

South Africa

The Republic of South Africa is a country in southern Africa. Located at the southern tip of Africa, it is divided into nine provinces, with of coastline on the Atlantic and Indian oceans...

, especially through rugby union

Rugby union

Rugby union, often simply referred to as rugby, is a full contact team sport which originated in England in the early 19th century. One of the two codes of rugby football, it is based on running with the ball in hand...

. Until the 1970s this resulted in discrimination against Māori players, since the apartheid political system in South Africa for most of the twentieth century did not allow people of different races to play sport together, and therefore South African officials requested that Māori players not be included in sides which toured their country. Despite some of New Zealand's best players being Māori, this was agreed to, and Māori were excluded from tours of South Africa. Some Māori always objected to this, but it did not become a major issue until 1960, when there were several public protests at Māori exclusion from that year's tour. The protest group Halt All Racist Tours

Halt All Racist Tours

Halt All Racist Tours was a protest group set up in New Zealand in 1969 to protest against rugby union tours to and from South Africa.-Chronology:...

was formed in 1969. Although this was an issue in which Māori were central, and Māori were involved in the protests, the anti-tour movement was dominated by Pākehā.

In 1973 a proposed Springbok

South Africa national rugby union team

The South African national rugby union team are 2009 British and Irish Lions Series winners. They are currently ranked as the fourth best team in the IRB World Rankings and were named 2008 World Team of the Year at the prestigious Laureus World Sports Awards.Although South Africa was instrumental...

(South African rugby team) tour of New Zealand was cancelled. In 1976 the South African government relented and allowed a mixed-race All Black team to tour South Africa. However by this time international opinion had turned against any sporting contact with South Africa, and New Zealand faced significant international pressure to cut ties. Despite this, in 1981 the Springboks toured New Zealand, sparking mass protests and civil disobedience

Civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal to obey certain laws, demands, and commands of a government, or of an occupying international power. Civil disobedience is commonly, though not always, defined as being nonviolent resistance. It is one form of civil resistance...

. Although Pākehā continued to dominate the movement, Māori were prominent within it, and in Auckland

Auckland

The Auckland metropolitan area , in the North Island of New Zealand, is the largest and most populous urban area in the country with residents, percent of the country's population. Auckland also has the largest Polynesian population of any city in the world...

formed the patu

Patu

A patu is a generic term for a club or pounder used by the Māori, the indigenous people of New Zealand. The word patu in the Māori language means to strike, hit, beat, or subdue. .- Weapons :...

squad in order to remain autonomous within the wider movement.

During and after the Tour, many Māori protesters questioned Pākehā protesters' commitment to racial equality, accusing them of focussing on racism in other countries while ignoring it within New Zealand. The majority of Pākehā protesters were not heavily involved in protest after the Tour ended, but a significant minority, including several anti-Tour groups, turned their attention to New Zealand race issues, particularly Pākehā prejudice and the Treaty of Waitangi.

Waitangi Day protests

The first act of the Māori protest movement was arguably the boycott of Waitangi DayWaitangi Day

Waitangi Day commemorates a significant day in the history of New Zealand. It is a public holiday held each year on 6 February to celebrate the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand's founding document, on that date in 1840.-History:...

by a handful of Māori elders in 1968 in protest over the Māori Affairs Amendment Act. A small protest was also held at parliament, and was received by Labour

New Zealand Labour Party

The New Zealand Labour Party is a New Zealand political party. It describes itself as centre-left and socially progressive and has been one of the two primary parties of New Zealand politics since 1935....

MP Whetu Tirikatene-Sullivan

Whetu Tirikatene-Sullivan

Tini "Whetu" Marama Tirikatene-Sullivan, ONZ was a New Zealand politician. She was an MP from 1967 to 1996, representing the Labour Party. At the time of her retirement, she was the second longest-serving MP in Parliament, being in her tenth term of office...

. Although both were reported in the newspapers they made little impact. In 1971 the ceremonies were disrupted by the protest group Ngā Tamatoa

Nga Tamatoa

Ngā Tamatoa was a Māori activist group that operated from the early 1970s until 1979, and existed to fight for Maori rights, land and culture as well as confront injustices perpetrated by the New Zealand Government, particularly violations of the Treaty of Waitangi.Nga Tamatoa emerged out of a...

(The Young Warriors) who chanted and performed haka

Haka

Haka is a traditional ancestral war cry, dance or challenge from the Māori people of New Zealand. It is a posture dance performed by a group, with vigorous movements and stamping of the feet with rhythmically shouted accompaniment...

during speeches, and attempted to destroy the flag. Protest has been a feature of Waitangi Day ever since.

Māori language and culture activism

One of the early goals of the Māori protest movement was the promotion of Māori languageMaori language

Māori or te reo Māori , commonly te reo , is the language of the indigenous population of New Zealand, the Māori. It has the status of an official language in New Zealand...

(te reo Māori) and culture

Maori culture

Māori culture is the culture of the Māori of New Zealand, an Eastern Polynesian people, and forms a distinctive part of New Zealand culture. Within the Māori community, and to a lesser extent throughout New Zealand as a whole, the word Māoritanga is often used as an approximate synonym for Māori...

. Both of these had been generally ignored by the education system and New Zealand society in general, and schoolchildren were actively discouraged from speaking Māori in school (the 1867 Native Schools Act decreed that English should be the only language used in the education of Māori children- this policy was later rigorously enforced ).This movement was led by Maori Mps who saw the advantages of Maori becomming fluent in a dominant world language. Until Māori became largely urbanised after World War II, this did not seriously damage the language since most Māori spoke it in their rural communities. Urbanisation produced a generation of Māori who mostly grew up in non-Māori environments and were therefore less exposed to the language. In addition, many parents felt that it was much more important for their children to be fluent in English and made no attempts to pass on the language. As a result, many leaders of Māori protest were not fluent in Māori and felt that this was a major cultural loss. In the face of official indifference and sometimes hostility, Nga Tamatoa and other groups initiated a number of schemes for the promotion of the language. These included Māori Language Day, which later became Māori Language Week

Maori Language Week

Māori Language Week, te wiki o te reo Māori, is a government-sponsored initiative intended to encourage New Zealanders to promote the use of Māori language. Māori, English and New Zealand Sign Language are the official national languages of New Zealand...

; a programme which trained fluent speakers as teachers; and kohanga reo

Kohanga reo

The Māori language revival is a movement to promote, reinforce and strengthen the speaking of the Māori language. Primarily in New Zealand, but also in centres with large numbers of New Zealand migrants , the movement aims to increase the use of Māori in the home, in education, government and...

: Māori language pre-schools and later Maori kura or separate immersion schools at primary and secondary level. Later there were campaigns for a Māori share of the airwaves. These eventually resulted in the iwi radio stations and a Māori Television

Maori Television

Māori Television is a New Zealand TV station broadcasting programmes that make a significant contribution to the revitalisation of the Māori language and culture . Funded by the New Zealand Government, the station started broadcasting on 28 March 2004 from a base in Newmarket.Te Reo is the...

channel, all of which actively promote the language. In 1987 Te Reo was made an official language

Official language

An official language is a language that is given a special legal status in a particular country, state, or other jurisdiction. Typically a nation's official language will be the one used in that nation's courts, parliament and administration. However, official status can also be used to give a...

of New Zealand, with the passing of the Māori Language Act

Maori Language Act

The Māori Language Act 1987 was a piece of legislation passed by the New Zealand Parliament. It gave Te Reo Māori official language status, and gave speakers a right to use it in legal settings such as in court...

. Activists also campaigned to change the names of landmarks such as mountains back to their original Māori names, and to end the mispronunciation of Māori words, especially by newsreaders and other broadcasters.

Many Māori cultural forms, such as carving, weaving and performing arts such as haka

Haka

Haka is a traditional ancestral war cry, dance or challenge from the Māori people of New Zealand. It is a posture dance performed by a group, with vigorous movements and stamping of the feet with rhythmically shouted accompaniment...

had gone into decline in the nineteenth century. From the early twentieth century Apirana Ngata

Apirana Ngata

Sir Apirana Turupa Ngata was a prominent New Zealand politician and lawyer. He has often been described as the foremost Māori politician to have ever served in Parliament, and is also known for his work in promoting and protecting Māori culture and language.-Early life:One of 15 children, Ngata...

and others had made efforts to revive them, for example setting up inter-tribal kapa haka

Kapa haka

The term Kapa haka is commonly known in Aotearoa as 'Maori Performing Arts' or the 'cultural dance' of Maori people...

competitions and getting state funding for meeting houses. Māori activists continued this tradition, but their primary focus was on stopping the abuse of Māori cultural forms. The best known example of this was the 'haka party' incident. A group of University of Auckland

University of Auckland

The University of Auckland is a university located in Auckland, New Zealand. It is the largest university in the country and the highest ranked in the 2011 QS World University Rankings, having been ranked worldwide...

engineering students had for many years performed a parody haka and paddled an imaginary waka

Waka (canoe)

Waka are Māori watercraft, usually canoes ranging in size from small, unornamented canoes used for fishing and river travel, to large decorated war canoes up to long...

around central Auckland as a capping stunt

Capping stunt

A capping stunt or capping is a New Zealand university tradition of student pranks wherein students perpetrate hoaxes or practical jokes upon an unsuspecting population...

. Repeated requests to end the performance were ignored and eventually a group of Māori assaulted the students. Although the activists' actions were widely condemned by Pākehā, they were defended in court by Māori elders and were convicted but the students' stunt was not performed again. Most recent Māori protest in this sphere has been directed against non-New Zealand groups and businesses who use the Māori language and cultural forms - sometimes copyrighting them - without permission or understanding. Since it is internationally known, the haka of the All Blacks

Haka of the All Blacks

The Haka is a traditional Maori war dance from New Zealand. There are thousands of Haka that are performed by various tribes and cultural groups throughout New Zealand. The best known Haka of them all is called "Ka Mate". It has been performed by countless New Zealand teams both locally and...

is particularly vulnerable to this treatment.

The Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of WaitangiTreaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi is a treaty first signed on 6 February 1840 by representatives of the British Crown and various Māori chiefs from the North Island of New Zealand....

has always been a major focus of Māori protest. It is often used to argue for particular aims, such as return of unjustly taken land, and the promotion of the Māori language.

The Treaty to the mid 20th century

The Treaty of Waitangi was an agreement, made in 1840, between the British Crown and various Māori chiefs. Although major differences between the Māori and English language versions of the Treaty make it difficult to ascertain exactly what was promised to who, the Treaty essentially gave the British the right to establish a governor in New Zealand, stated the rights of the chiefs to ownership of their lands and other properties, and gave Māori the rights of British citizens. Although the Treaty is generally seen as marking the beginning of the New Zealand nation, it was largely ignored for more than a century after its signing, and various legal judgements ruled it irrelevant to New Zealand law and government. Despite this, Māori frequently used it to argue that their rights were being denied.Campaign for ratification

From about the mid nineteenth century, Māori campaigned for proper recognition of the Treaty, generally asking that it be ratified or otherwise made a part of New Zealand law. In the 1960s and the 1970s, Māori activists continued this campaign, sometimes making it a focus of their Waitangi DayWaitangi Day

Waitangi Day commemorates a significant day in the history of New Zealand. It is a public holiday held each year on 6 February to celebrate the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand's founding document, on that date in 1840.-History:...

protests. In 1975 the Treaty was given some recognition with the Treaty of Waitangi Act

Treaty of Waitangi Act

The Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 established the Waitangi Tribunal and gave the Treaty of Waitangi recognition in New Zealand law for the first time. The Tribunal was empowered to investigate possible breaches of the Treaty by the New Zealand government or any state-controlled body, occurring after...

. This established the Waitangi Tribunal

Waitangi Tribunal

The Waitangi Tribunal is a New Zealand permanent commission of inquiry established under the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975...

, which was given the task to investigating contemporary breaches of the Treaty. However since it was not able to investigate historical breaches, was underfunded, and generally unsympathetic to claimants, most Māori were disappointed by the Tribunal.

"The Treaty is a Fraud"

Possibly as a result to the failure of the Waitangi Tribunal to achieve much, many Māori activists in the early 1980s stopped asking for the Treaty to be honoured and instead argued that it was a fraudulent document. They argued that Māori had been tricked in 1840, that either they had never agreed to sign away their sovereignty or that Pākehā breaches of the Treaty had rendered it invalid. Since the Treaty was invalid, it was argued, the New Zealand government had no right to sovereignty over the country. This argument was broadly expressed in Donna Awatere's book Māori Sovereignty.Activism and the Tribunal

In 1985 the Treaty of Waitangi Act was amended to allow the Tribunal to investigate historic breaches of the Treaty. It was also given more funding and its membership increased. In addition, the Treaty was mentioned in several pieces of legislation, and a number of court cases increased its importance. As a result, most Māori activists began to call once again for the Treaty to be honoured. Many protesters put their energies into Treaty claims and the management of settlements, but many also argued that the Tribunal was too underfunded and slow, and pointed out that because its recommendations were not binding the government could (and did) ignore it when it suited them. Some protesters continued to argue for Māori sovereignty, arguing that by negotiating with the Tribunal Māori were only perpetuating the illegal occupying government.Land

The longest-standing Māori grievances generally involve land. In the century after 1840 Māori lost possession of most of their land, although the amount lost varied significantly between iwiIwi

In New Zealand society, iwi form the largest everyday social units in Māori culture. The word iwi means "'peoples' or 'nations'. In "the work of European writers which treat iwi and hapū as parts of a hierarchical structure", it has been used to mean "tribe" , or confederation of tribes,...

. In some cases the land was purchased legitimately from willing Māori sellers, but in many cases the transfer was legally and/or morally dubious. The best known cause of Māori land loss is the confiscation

Confiscation

Confiscation, from the Latin confiscatio 'joining to the fiscus, i.e. transfer to the treasury' is a legal seizure without compensation by a government or other public authority...

in the Waikato

Waikato

The Waikato Region is a local government region of the upper North Island of New Zealand. It covers the Waikato, Hauraki, Coromandel Peninsula, the northern King Country, much of the Taupo District, and parts of Rotorua District...

and Taranaki regions following the New Zealand Land Wars

New Zealand land wars

The New Zealand Wars, sometimes called the Land Wars and also once called the Māori Wars, were a series of armed conflicts that took place in New Zealand between 1845 and 1872...

. Other causes included owners selling land without fully understanding the implications of the sale (especially in the early years of colonisation); groups selling land which did not belong to them; Pākehā traders enticing land owners into debt and then claiming the land as payment; the conducting of unrequested surveys which were then charged to the owners, and the unpaid bills from this used to justify taking the land; levying of unreasonable rates and confiscation following non-payment; the taking of land for public works

Public works

Public works are a broad category of projects, financed and constructed by the government, for recreational, employment, and health and safety uses in the greater community...

; and simple fraud. Upon losing land, most iwi quickly embarked on campaigns to regain it but these were largely unsuccessful. Some iwi received token payments from the government but continued to agitate for the return of the land or, failing that, adequate compensation.

The return of lost land was a major focus of Māori activists, and generally united the older, more conservative generation with the younger 'protest' generation. Some of the best-known episodes of Māori protest centred on land, including:

Bastion Point

Bastion PointBastion Point

Bastion Point is a coastal piece of land in Orakei, Auckland, New Zealand, overlooking the Waitemata Harbour. The area has significance in New Zealand history for its role in 1970s Māori protests against forced land alienation by non Māori New Zealanders.-History:The land was occupied by Ngāti...

in Auckland

Auckland

The Auckland metropolitan area , in the North Island of New Zealand, is the largest and most populous urban area in the country with residents, percent of the country's population. Auckland also has the largest Polynesian population of any city in the world...

was originally part of a large area of land owned by Ngati Whatua

Ngati Whatua

Ngāti Whātua is a Māori iwi of New Zealand. It consists of four hapu : Te Uri-o-Hau, Te Roroa, Te Taoū, and Ngāti Whātua-o-Ōrākei....

. Between 1840 and 1960 nearly all of this was lost, leaving Ngati Whatua with only the Point. In the 1970s the third National government

Third National Government of New Zealand

The Third National Government of New Zealand was the government of New Zealand from 1975 to 1984. It was an economically and socially conservative government, which aimed to preserve the Keynesian economic system established by the First Labour government while also being socially conservative...

proposed taking the land and developing it. Bastion Point was subsequently occupied in a protest which lasted from January 1977 to May 1978. The protesters were removed by the army and police, but there continued to be conflict over the land. When the Waitangi Tribunal was given the power to investigate historical grievances, this the Orakei

Orakei

Orakei is a suburb of Auckland city, in the North Island of New Zealand. It is located on a peninsula five kilometres to the east of the city centre, close to the shore of the Waitemata Harbour, which lies to the north, and Hobson Bay and the Orakei Basin, two arms of the Waitemata, which lie to...

claim covering the Bastion Point area was one of the first cases for investigation. The Tribunal found that Ngati Whatua had been unjustly deprived of their ancestral land hence Bastion Point was returned to their ownership with compensation paid to the tribe by the Crown.

Raglan Golf Course

During the Second World War, land in the Raglan area was taken from its Māori owners for use as an airstrip. Following the end of the war, the land was not returned but instead leased to the Raglan Golf Club, who turned it into a golf course. This was particularly painful for the original owners as it contained burial grounds, one of which was turned into a bunkerBunker (golf)

A hazard is an area of a golf course in the sport of golf which provides a difficult obstacle. which may be of three types: water hazards such as lakes and rivers; man-made hazards such as bunkers; and natural hazards such as dense vegetation. Special rules apply to playing balls that fall in a...

. A group of protesters led by Eva Rickard

Eva Rickard

Eva Rickard rose to prominence as an activist for Māori land rights activist and for women’s rights within Māoridom. Her methods included public civil disobedience and she is best known for leading the occupation of Raglan golf course in the 1970s.-Biography:Eva Rickard was most notably regarded...

and assisted by Angeline Greensill

Angeline Greensill

Angeline Ngahina Greensill is a prominent Māori political rights campaigner, academic and leader.-Early life:Greensill is of Tainui, Ngati Porou, and Ngati Paniora descent, born in the late 1940s in Kirikiriroa and raised at Te Kopua , Whaingaroa on the turangawaewae of Tainui o Tainui ki...

occupied the land and also used legal means to have the land returned, a goal which was eventually achieved.

1975 Land March

In 1975 a large group (around 5000) of Māori and other New Zealanders, led by then 79-year-old Whina CooperWhina Cooper

Dame Whina Cooper ONZ DBE , was born Hohewhina Te Wake, daughter of Heremia Te Wake of the Te Rarawa iwi, at Te Karaka, Hokianga,...

, walked the length of the North Island

North Island

The North Island is one of the two main islands of New Zealand, separated from the much less populous South Island by Cook Strait. The island is in area, making it the world's 14th-largest island...

to Wellington

Wellington

Wellington is the capital city and third most populous urban area of New Zealand, although it is likely to have surpassed Christchurch due to the exodus following the Canterbury Earthquake. It is at the southwestern tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Rimutaka Range...

to protest against Māori land loss. Although the government at the time, the third Labour government

Third Labour Government of New Zealand

The Third Labour Government of New Zealand was the government of New Zealand from 1972 to 1975. During its time in office, it carried out a wide range of reforms in areas such as overseas trade, farming, public works, energy generation, local government, health, the arts, sport and recreation,...

, had done more to address Māori grievances than nearly any prior government, protesters felt that much more needed to be done. Following the march, the protesters were divided over what to do next. Some, including Tame Iti

Tame Iti

Tāme Wairere Iti has become well known in New Zealand as a Tūhoe Māori activist.- Early life :Born on a train near Rotorua, Tame Iti grew up with his grandparents in the custom known as whāngai on a farm near Ruatoki in the Urewera area of New Zealand...

, remained in Wellington to occupy parliament grounds. A 1975 documentary from director Geoff Steven includes interviews with many of those on the march: Eva Rickard

Eva Rickard

Eva Rickard rose to prominence as an activist for Māori land rights activist and for women’s rights within Māoridom. Her methods included public civil disobedience and she is best known for leading the occupation of Raglan golf course in the 1970s.-Biography:Eva Rickard was most notably regarded...

, Tama Poata

Tama Poata

Tama Te Kapua Poata was a New Zealand writer, actor, humanitarian and activist. He was from the Māori tribe of Ngati Porou. He was also known as 'Tom,' the transliteration of 'Tama.'-Background:...

and Whina Cooper

Whina Cooper

Dame Whina Cooper ONZ DBE , was born Hohewhina Te Wake, daughter of Heremia Te Wake of the Te Rarawa iwi, at Te Karaka, Hokianga,...

.

Resurgence of protest on land and Treaty issues in the 1990s

A series of protests in the mid-1990s marked a new phase of activism on land and Treaty issues with action focussed not only on the Government but also Maori conservatives who were seen as being complicit with the Government agenda. Symbolic acts included attacking Victorian statuary, the America's Cup and the lone pine on One Tree HillOne Tree Hill, New Zealand

One Tree Hill is a 182 metre volcanic peak located in Auckland, New Zealand. It is an important memorial place for both Māori and other New Zealanders...

and removing a Colin McCahon painting (subsequently returned) from the Lake Waikaremoana

Lake Waikaremoana

Lake Waikaremoana is located in Te Urewera National Park in the North Island of New Zealand, 60 kilometres northwest of Wairoa and 80 kilometres southwest of Gisborne. It covers an area of 54 km². From the Maori Waikaremoana translates as 'sea of rippling waters'The lake lies in the heart of Tuhoe...

Visitor Centre. Rising protests at the Waitangi Day

Waitangi Day

Waitangi Day commemorates a significant day in the history of New Zealand. It is a public holiday held each year on 6 February to celebrate the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand's founding document, on that date in 1840.-History:...

celebrations led the government to move the official observance to Government House in Wellington. Many protests were generated in response to the government's proposal to limit the monetary value of Treaty settlements to one billion dollars over 10 years, the so-called fiscal envelope. A series of hui (meetings) graphically illustrated the breadth and depth of Maori rejection of such a limitation in advance of the extent of claims being fully known. As a result, much of the policy package, especially the fiscal cap, was dropped. These protests included occupations of Whanganui's Moutoa Gardens and the Takahue school in Northland (leading to its destruction by fire).

Fiscal Envelope

The government unveils the fiscal envelope — its answer to settling Treaty of Waitangi grievances limiting the total amount that will be spent to one billion dollars. While early Tribunal recommendations mainly concerned a contemporary issue that could be revised or rectified by the government at the time, historical settlements raised more complex issues. The Office of Treaty SettlementsOffice of Treaty Settlements

The Office of Treaty Settlements is an office within the Ministry of Justice tasked with negotiating treaty settlements...

was established in the Ministry of Justice to develop government policy on historical claims. In 1995, the government developed the "Crown Proposals for the Settlement of Treaty of Waitangi Claims" to attempt to address the issues. A key element of the proposals was the creation of a "fiscal envelope" of $1 billion for the settlement of all historical claims, an effective limit on what the Crown would pay out in settlements. The Crown held a series of consultation hui

Hui (Maori assembly)

A hui is a New Zealand term for a social gathering or assembly.Originally a Māori language word, it was used by Europeans as early as 1846 when referring to Māori gatherings - but is now increasingly used in New Zealand English to describe events that are not exclusively Māori....

around the country, at which Māori vehemently rejected such a limitation in advance of the extent of claims being fully known. The concept of the fiscal envelope was subsequently dropped after the 1996 general election

New Zealand general election, 1996

The 1996 New Zealand general election was held on 12 October 1996 to determine the composition of the 45th New Zealand Parliament. It was notable for being the first election to be held under the new Mixed Member Proportional electoral system, and produced a parliament considerably more diverse...

. Opposition to the policy was coordinated by Te Kawau Maro an Auckland group who organised protests at the Government consultation Hui. Rising protests to the Fiscal Envelope at the Waitangi Day

Waitangi Day

Waitangi Day commemorates a significant day in the history of New Zealand. It is a public holiday held each year on 6 February to celebrate the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand's founding document, on that date in 1840.-History:...

celebrations led the government to move the official observance to Government House in Wellington. Despite universal rejection of the 'Fiscal Envelope', Waikato-Tainui negotiators, accepted the Government Deal which became known as the Waikato Tainui Raupatu Settlement. Notable opposition to this deal was led by Maori leader Eva Rickard

Eva Rickard

Eva Rickard rose to prominence as an activist for Māori land rights activist and for women’s rights within Māoridom. Her methods included public civil disobedience and she is best known for leading the occupation of Raglan golf course in the 1970s.-Biography:Eva Rickard was most notably regarded...

.

Pākaitore

For 79 days in 1995, people of the Whanganui tribes occupied historic Pākaitore (Moutoa Gardens), beside the river and within the city of Whanganui. This protest was resolved peaceably, and a tripartite agreement with government and local government has since been signed. At the heart of all this is the Whanganui tribes’ claim to the river, which is still seen as both an ancestor and a source of material and spiritual sustenance."We were forced to leave, and it shouldn't be lost on anybody that we upheld our dignity," protest leader Ken Mair

Ken Mair

Ken Mair is a New Zealand political activist and politician. He was ranked seventh on the Mana Maori party list for the 1999 New Zealand general election, and second on their party list for the 2002 New Zealand general election....

told a press conference in Whanganui May 18, 1995 following the end of the occupation." In no way were we going to allow the state the opportunity to put the handcuffs on us and lock us away."

The police were reported to have up to 1,000 reinforcements ready to evict the land occupants. Whanganuí Kaitoke prison had been gazetted as a "police jail" to enable its use as holding cells. The police eviction preparations were code-named "Operation Exodus".

A week earlier, on May 10, up to 70 police in riot gear had raided the land occupation in the middle of the night, claiming the protest had become a haven for "criminals and stolen property" and "drug users." Ten people were arrested on minor charges including "breach of the peace" and "assault." Throughout the occupation there has been a strict policy of no drugs or alcohol on the site.

Protest leaders denounced the raid as a dress rehearsal for their forced eviction and an attempt to provoke, intimidate, and discredit the land occupants. Throughout the 79-day occupation, the land protesters faced almost nightly harassment and racist abuse by the police.

The decision to end the Maori occupation of Moutoa Gardens was debated by participants at a three-hour meeting May 17, 1995. At 3:45 the next morning the occupants gathered and began dismantling tents and buildings and the surrounding fence. Bonfires burned across the site.

At 4:50 a.m., the same time they had entered the gardens 79 days earlier, the protesters began their march to a meeting place several miles away. Over the next few days, a team continued to dismantle the meeting house and other buildings that had been erected during the occupation.

"Every step of the way has been worthwhile as far as we are concerned," Niko Tangaroa told the May 18 press conference in Wanganui. "Pakaitore is our land. It will remain our land, and we will continue to assert that right irrespective of the courts."

The protest leaders vowed to continue their fight, including through further land occupations. "As long as the Crown [government] buries its head in the sand and pretends that issues of sovereignty and our land grievances are going to go away- we are going to stand up and fight for what is rightfully ours," Ken Mair

Ken Mair

Ken Mair is a New Zealand political activist and politician. He was ranked seventh on the Mana Maori party list for the 1999 New Zealand general election, and second on their party list for the 2002 New Zealand general election....

declared.

Takahue

The Whanganui occupation of Pakaitore inspired a group of Maori from Takahue a small Northland settlement to occupy the local schoolhouse. The several dozen protesters who have occupied the school since then are demanded that title to the land on which the school stands be returned to them.The 6 acres (24,281.2 m²) they claimed were part of 4500 acres (18.2 km²) purchased by the government in 1875, in a transaction the protesters, descendants of the original owners, regard as invalid. The school has been closed since the mid 1980s and used as an army training camp and for community activities since then.

Bill Perry, a spokesperson for the protesters, explained to reporters who visited the occupation April 22 in 1995 that the land they are claiming has been set aside in a government controlled Landbank together with other property in the region. This Landbank allegedly protects lands currently subject to claims under the Waitangi Tribunal from sale pending settlement of the claims.

The occupation ended with mass arrests and the burning of the school.

Huntly

Another occupation inspired by Pakaitore began on April 26, 1995 in Huntly a coal mining town south of Auckland. The block of land sits atop a hill overlooking the town, in full view of the mine entrance with its coal conveyor leading to a power station.Protesters told reporters who visited the occupation April 29 that the land is part of 1200000 acres (4,856.2 km²) confiscated by the government 132 years ago from the Tainui tribe. It is now owned by Coalcorp, a private coal company that was previously state-owned. Most coal miners in New Zealand lost their jobs when the government-run coal industry was transformed into a state-owned corporation in 1987, prior to its privatization.

Those occupying the land are demanding its return to Ngati Whawhakia, the local Maori sub-tribe. The claim includes coal and mineral rights.

Robert Tukiri, chairman of Ngati Whawhakia Trust and spokesperson for the occupation said, "We have got our backs to the wall. There is a housing shortage. We need to have houses."

Tukiri opposed a NZ$170 million (NZ$1=US$0.67) deal between the government and the Tainui Maori Trust Board due to be signed May 22 as final settlement for the government's land seizures last century. The agreement will turn over 86000 acres (348 km²) of state-owned land to the trust board and NZ$65 million for further purchases of private land.

"The Tainui Maori Trust Board stands to become the biggest landlord around, while 80 percent of our tribe rents their homes," Tukiri commented.

Foreshore and Seabed

In 2003 the Court of Appeal ruled that Māori could seek customary title to areas of the New Zealand foreshore and seabed

Seabed

The seabed is the bottom of the ocean.- Ocean structure :Most of the oceans have a common structure, created by common physical phenomena, mainly from tectonic movement, and sediment from various sources...

, overturning assumptions that such land automatically belonged to the Crown. The ruling alarmed many Pākehā, and the Labour government

Fifth Labour Government of New Zealand

The Fifth Labour Government of New Zealand was the government of New Zealand between 10 December 1999 and 19 November 2008.-Overview:The fourth National government, in power since 1990, was widely unpopular by 1999, with much of the public antagonised by a series of free-market economic reforms,...

proposed legislation removing the right to seek ownership of the foreshore and seabed. This angered many Māori who saw it as confiscation of land. Labour Party

New Zealand Labour Party

The New Zealand Labour Party is a New Zealand political party. It describes itself as centre-left and socially progressive and has been one of the two primary parties of New Zealand politics since 1935....

MP Tariana Turia

Tariana Turia

Tariana Turia is a New Zealand politician. She gained considerable prominence during the foreshore and seabed controversy, and eventually broke with her party as a result...

was so incensed by the legislation that she eventually left the party and formed the Māori Party

Maori Party

The Māori Party, a political party in New Zealand, was formed on 7 July 2004. The Party is guided by eight constitutional "kaupapa", or Party objectives. Tariana Turia formed the Māori Party after resigning from the Labour Party where she had been a Cabinet Minister in the Fifth Labour-led...

. In May 2004 a hikoi

Hikoi

Hikoi is a term of the Maori language of New Zealand generally meaning a protest march or parade, usually implying a long journey taking days or weeks....

(march) from Northland to Wellington, modelled on the 1975 land march but in vehicles, was held, attracting thousands of participants. Despite this, the legislation was passed later that year.

Te Mana Motuhake o Tuhoe

Te Mana Motuhake o Tuhoe is a group which includes popular Tuhoe leader Tame ItiTame Iti

Tāme Wairere Iti has become well known in New Zealand as a Tūhoe Māori activist.- Early life :Born on a train near Rotorua, Tame Iti grew up with his grandparents in the custom known as whāngai on a farm near Ruatoki in the Urewera area of New Zealand...

. The group has held numerous campaigns highlighting the rights of the Tuhoe

Tuhoe

Ngāi Tūhoe , a Māori iwi of New Zealand, takes its name from an ancestral figure, Tūhoe-pōtiki. The word tūhoe literally means "steep" or "high noon" in the Māori language...

people. The ideology of the group is based on self-government as a base principle of democracy and that Tuhoe has the democratic right to self-government. Tuhoe were not signatories of the Treaty of Waitangi, and have always maintained a right to uphold uniquely Tuhoe values, culture, language and identity within Tuhoe homelands.

Te Urupatu

On January 16, 2005 during a powhiriPowhiri

A Pōwhiri is a Māori welcoming ceremony involving speeches, dancing, singing and finally the hongi...

(or greeting ceremony) which formed part of a Waitangi Tribunal

Waitangi Tribunal

The Waitangi Tribunal is a New Zealand permanent commission of inquiry established under the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975...

hearing, Tāme Iti fired a shotgun

Shotgun

A shotgun is a firearm that is usually designed to be fired from the shoulder, which uses the energy of a fixed shell to fire a number of small spherical pellets called shot, or a solid projectile called a slug...

into a New Zealand

Flag of New Zealand

The flag of New Zealand is a defaced Blue Ensign with the Union Flag in the canton, and four red stars with white borders to the right. The stars represent the constellation of Crux, the Southern Cross....

flag in close proximity to a large number of people, which he explained was an attempt to recreate the 1860s East Cape War

East Cape War

The East Cape War, sometimes also called the East Coast War, refers to a series of conflicts that were fought in the North Island of New Zealand from about 13 April 1865 to June 1868...