Matterhorn

Encyclopedia

The Matterhorn Monte Cervino (Italian) or Mont Cervin (French), is a mountain in the Pennine Alps

on the border between Switzerland

and Italy

. Its summit is 4,478 metres (14,690 ft) high, making it one of the highest peaks in the Alps

. The four steep faces, rising above the surrounding glaciers, face the four compass points. The mountain overlooks the town of Zermatt

in the canton of Valais

to the north-east and Breuil-Cervinia in the Aosta Valley to the south. The Theodul Pass

, located at the eastern base of the peak, is the lowest passage between its north and south side.

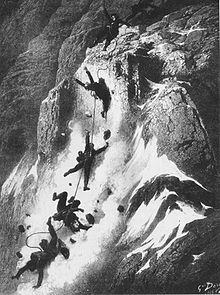

The Matterhorn was the last great Alpine peak to be climbed and its first ascent

marked the end of the golden age of alpinism

. It was made in 1865 by a party led by Edward Whymper

and ended disastrously when four of its members fell to their deaths on the descent. The north face was not climbed until 1931, and is amongst the six great north faces of the Alps

. The Matterhorn is one of the deadliest peaks in the Alps: from 1865 – when it was first climbed – to 1995, 500 alpinists died on it.

The Matterhorn has become an iconic emblem of the Swiss Alps

and the Alps

in general. Since the end of the 19th century, when railways were built, it attracted more and more visitors and climbers. Each summer a large number of mountaineers try to climb the Matterhorn via the northeast Hörnli ridge, the most popular route to the summit.

words Matte, meaning "meadow", and Horn, which means "peak". The migration of the name "meadow" from the lower part of the countryside to the peak is common in the Alps. The Italian

and French

names (Cervino and Cervin) come from Mons Silvius (or Mons Sylvius) from the Latin word silva, meaning forest (with again the migration of the name from the lower part to the peak). The changing of the first letter "s" to "c" is attributed to Horace Bénédict de Saussure, who thought that the word was related to a deer (French: cerf and Italian: cervo).

In Sebastian Münster

's Cosmography

, published in 1543, the name of Matter is given to the Theodul Pass

, and this seems to be the origin of the present German name of the mountain. On Münster's topographical chart this group is marked under the names of Augstalberg ("Aosta mountain") and Mons Silvius. An hypothesis of Josias Simler (De Alpibus Commentarius, 1574) on the etymology of the name of Mons Silvius was readopted by T. G. Farinetti: "Silvius was probably a Roman leader who sojourned with his legions in the land of the Salassi and the Seduni, and perhaps crossed the Theodul Pass between these two places. This Silvius may have been that same Servius Galba whom Caesar charged with the opening up of the Alpine passes, which from that time onward traders have been wont to cross with great danger and grave difficulty. Servius Galba, in order to carry out Caesar's orders, came with his legions from Allobrogi (Savoy) to Octodurum (Martigny) in the Valais, and pitched his camp there. The passes which he had orders to open from there could be no other than the St. Bernard, the Simplon, the Theodul, and the Moro; it therefore seems likely that the name of Servius, whence Silvius and later Servin, or Cervin, was given in his honour to the famous pyramid." It is not exactly known at what period the new name of Servin, or Cervin, replaced the old, from which it seems to be derived.

The Matterhorn is also named Gran Becca by the Valdôtain

s and Horu by the local Walliser German speaking people.

The Matterhorn is an isolated mountain. Because of its position on the main Alpine watershed and its great height, the Matterhorn is exposed to rapid weather changes. In addition the steep faces of the mountain and its isolated location make it prone to banner clouds

The Matterhorn is an isolated mountain. Because of its position on the main Alpine watershed and its great height, the Matterhorn is exposed to rapid weather changes. In addition the steep faces of the mountain and its isolated location make it prone to banner clouds

formation with the air flowing around and creating vortices, conducting condensation of the air on the lee side.

The Matterhorn has two distinct summits

, both situated on a 100-metre-long rocky ridge: the Swiss summit (4,477.5 m) on the east and the Italian summit (4,476.4 m) on the west. Their names originated from the first ascents, not for geographic reasons, as they are both located on the border. In August 1792, the Genevan geologist and explorer Horace Bénédict de Saussure made the first measurement of the Matterhorn's height, using a 50-foot-long chain spread out on the Theodul glacier and a sextant. He calculated a height of 4,501.7 metres. In 1868 the Italian engineer Felice Giordano

measured a height of 4,505 metres by means of a mercurial barometer, which he had taken up to the summit. The Dufour map, which was afterwards followed by the Italian surveyors, gave 4,482 metres, or 14,704 feet, as the height of the Swiss summit. A recent survey (1999) using Global Positioning System

technology has been made, allowing the height of the Matterhorn to be measured to within one centimetre accuracy, and its changes to be tracked. The result was 4477.54 metres (14,690 ft).

The Matterhorn has a pyramidal shape

The Matterhorn has a pyramidal shape

with four faces facing the four compass points: the north and east faces overlook, respectively, the Zmutt

valley and Gornergrat

ridge in Switzerland, the south face (the only one south of the Swiss-Italian border) fronts the resort town of Breuil-Cervinia, and the west face looks towards the mountain of Dent d'Hérens

which straddles the border. The north and south faces meet at the summit to form a short east-west ridge.

The Matterhorn's faces are steep, and only small patches of snow and ice cling to them; regular avalanche

s send the snow down to accumulate on the glacier

s at the base of each face, the largest of which is the Zmutt Glacier

to the west. The Hörnli ridge of the northeast (the central ridge in the view from Zermatt) is the usual climbing route

.

Well-known faces are the east and north, visible from Zermatt. The east face is 1,000 metres high and, because it is "a long, monotonous slope of rotten rocks", presents a high risk of rockfall, making its ascent dangerous. The north face is 1,200 metres high and is one of the most dangerous north faces in the Alps, in particular for its risk of rockfall and storms. The south face is 1,350 metres high and offers many different routes. The west face, the highest at 1,400 metres, has the fewest ascent routes.

The four main ridges separating the four faces are the main climbing routes. The least difficult technical climb, the Hörnli ridge (Hörnligrat), lies between the east and north faces, facing the town of Zermatt. To its west lies the Zmutt ridge (Zmuttgrat), between the north and west faces; this is, according to Collomb, "the classic route up the mountain, its longest ridge, also the most disjointed." The Lion ridge (Cresta del Leone), lying between the south and west faces is the Italian normal route and goes across Pic Tyndall

; Collomb comments, "A superb rock ridge, the shortest on the mountain, now draped with many fixed ropes, but a far superior climb compared with the Hörnli." Finally the south side is separated from the east side by the Furggen ridge (Furggengrat), according to Collomb "the hardest of the ridges [...] the ridge still has an awesome reputation but is not too difficult in good conditions by the indirect finish".

The border between Italy and Switzerland is the main Alpine watershed

, separating the drainage basin

on the Rhone

on the north (Mediterranean Sea

) and the Po River

on the south (Adriatic Sea

). The Theodul Pass

, located between the Matterhorn and Klein Matterhorn

, at 3,300 metres, is the lowest passage between the Valtournenche

and the Mattertal

. The pass was used as a crossover and trade route for the Romans and the Romanised Celts between 100 BC and 400 AC.

While the Matterhorn is the culminating point of the Valtournenche on the south, it is only one of the many 4000 metres summits of the Mattertal valley on the north, among which the Weisshorn

(4505 m), Dom (4545 m), Lyskamm

(4527 m) and the second highest in the Alps: Monte Rosa

(4634 m). The whole range of mountains forming a crown of summits around Zermatt. The deeply glaciated region between the Matterhorn and Monte Rosa is listed in the Federal Inventory of Landscapes and Natural Monuments

.

belonging to the Dent Blanche klippe

, an isolated part of the Austroalpine nappes

, lying over the Penninic nappes

. The Austroalpine nappes are part of the Apulian plate

, a small continent which broke up from Africa before the Alpine orogeny

. For this reason the Matterhorn has been popularized as an African mountain. The Austroalpine nappes are mostly common in the Eastern Alps.

The Swiss explorer and geologist Horace-Bénédict de Saussure

, inspired by the view of the Matterhorn, anticipated the modern theories of geology:

continent 200 million years ago into Laurasia

(containing Europe) and Gondwana

(containing Africa). While the rocks constituting the nearby Monte Rosa

remained in Laurasia, the rocks constituting the Matterhorn found themselves in Gondwana, separated by the newly formed Tethys Ocean

.

100 million years ago the extension of the Tethys Ocean stopped and the Apulian plate broke from Gondwana and moved toward the European continent. This resulted in the closure of the western Tethys by subduction

under the Apulian plate (with the Piemont-Liguria Ocean

first and Valais Ocean

later). The subduction of the oceanic crust left traces still visible today at the base of the Matterhorn (accretionary prism). The orogeny itself began after the end of the oceanic subduction when the European continental crust collided with the Apulian continent, resulting in the formation of nappe

s.

The Matterhorn acquired its characteristic pyramidal shape in much more recent times as it was caused by natural erosion over the past million years. At the beginning of alpine orogeny, the Matterhorn was only a rounded mountain like a hill. Because its height is above the snowline, its flanks are covered by ice, resulting from the accumulation and compaction of snow. During the warmer period of summer, part of the ice melts and seeps into the bedrock. When it freezes again, it fractures pieces of rock because of its dilatation (freeze-thaw), forming a cirque

. Four cirques led to the shape of the mountain. Because of its recognizable shape, many other similar mountains around the world were named or nicknamed the 'Matterhorn' of their respective countries or mountain ranges.

) and its sedimentary rocks. Up to 3,400 metres the mountain is composed of successive layers of ophiolites and sedimentary rock

s. From 3,400 metres to the top, the rocks are gneisses from the Dent Blanche nappe (Austroalpine nappes). They are divided into the Arolla series (below 4,200 m) and the Valpelline zone (the summit). Other mountains in the region (Weisshorn, Zinalrothorn, Dent Blanche, Mont Collon) also belong to the Dent Blanche nappe.

caused a rush on the mountains surrounding Zermatt

.

The construction of the railway linking the village of Zermatt from the town of Visp

started in 1888. The first train reached Zermatt on July 18, 1891 and the entire line was electrified in 1930. Since 1930 the village is directly connected to St. Moritz

by the Glacier Express

panoramic train. However there is no connection with the village of Breuil-Cervinia

on the Italian side. Travellers have to hire mountain guides to cross the 3,300 metres high glaciated Theodul Pass

, separating the two resorts. The town of Zermatt remains completely free of internal combustion vehicles and can be reached by train only. (Electric vehicles are used locally).

Rail and cable-car facilities have been built to make some of the summits in the area more accessible. The Gornergrat

railway, reaching a record altitude of 3,100 metres, was inaugurated in 1898. Areas served by cable car are the Unterrothorn

and the Klein Matterhorn

(Little Matterhorn) (3,883 m, highest transportation system in Europe). The Hörnli Hut

(3,260 m), which is the start of the normal route via the Hörnli ridge, is easily accessible from Schwarzsee

(2,600 m) and is also frequented by hikers. Both resorts of Zermatt and Cervinia function as ski resort all year round and are connected by skilifts over the Theodul Pass. A cable car running from Testa Grigia to Klein Matterhorn is currently planned for 2014. It will finally provide a link between the Swiss and Italian side of the Matterhorn.

The Matterhorn Museum

(Zermatt) relates the general history of the region from alpinism to tourism. In the museum, which is in the form of a reconstituted mountain village, the visitors can relive the first and tragic ascent of the Matterhorn and see the objects having belonged to the protagonists.

The Tour of the Matterhorn can be effected by trekkers in about 10 days. Considered by some as one of the most beautiful treks in the Alps, it follows many ancient trails that have linked the Swiss and Italian valleys for centuries. The circuit includes alpine meadows, balcony trails, larch forests and glacial crossings. It connects six valleys embracing three different cultures: the German speaking high Valais, the French speaking central Valais and the Italian speaking Val d'Aosta. Good conditions are necessary to circumnavigate the peak. After reaching Zinal

by the Augstbord and Meiden passes, the trekker crosses the Torrent before arriving at Arolla

. Then the Col Collon

must be crossed on the road to Prarayer and another one to Breuil-Cervinia and back to Zermatt via the Theodul. In total, seven passes between 2,800 and 3,300 metres must be crossed on a relatively difficult terrain.

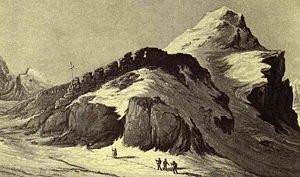

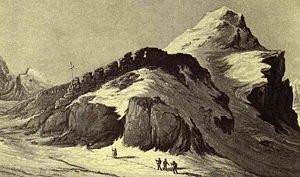

The Matterhorn was one of the last of the main Alpine

The Matterhorn was one of the last of the main Alpine

mountains to be ascended, not because of its technical difficulty, but because of the fear it inspired in early mountaineers

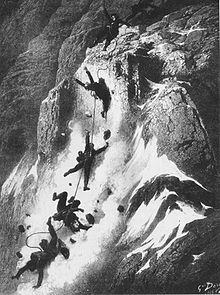

. The first serious attempts began around 1857, mostly from the Italian side; but despite appearances, the southern routes are harder, and parties repeatedly found themselves having to turn back. However, on July 14, 1865, in what is considered the last ascent of the golden age of alpinism

, the English

party of Edward Whymper

, Charles Hudson, Lord Francis Douglas

, Douglas Robert Hadow

, Michel Croz

and the two Peter Taugwalders (father and son) were able to reach the summit by an ascent of the Hörnli ridge in Switzerland. Upon descent, Hadow, Croz, Hudson and Douglas fell to their deaths on the Matterhorn Glacier, and all but Douglas (whose body was never found) are buried in the Zermatt churchyard.

Only three days after Whymper's ascent, the mountain was ascended from the Italian side via an indirect route by Jean-Antoine Carrel and Jean-Baptiste Bich on July 17, 1865.

. Although the unclimbed Matterhorn had a mixed reputation among British mountaineers, it fascinated Whymper. Whymper's first attempt was in 1861, from the village of Breuil on the south side. He was at the beginning of the climb, with a Swiss guide, when he met Jean-Antoine Carrel

and his uncle. Carrel was an Italian guide from Breuil who had already made several attempts on the mountain. The two parties camped together at the base of the peak. Carrel and his uncle woke up early and decided to continue the ascent without Whymper and his guide. Discovering that they had been left, Whymper and his guide tried to race Carrel up the mountain, but neither party met with success.

In 1862 Whymper made further attempts, still from the south side, on the Lion ridge (or Italian ridge), where the route seemed easier than the Hörnli ridge (the normal route today). On his own he reached above 4,000 metres, but was injured on his way down to Breuil. In July John Tyndall

with Johann Joseph Bennen and another guide overcame most of the difficulties of the ridge that seemed so formidable from below and successfully reached the main shoulder

; but at a point not very far below the summit they were stopped by a deep cleft that defied their utmost efforts. The Matterhorn remained unclimbed.

Whymper returned to Breuil in 1863, persuading Carrel to join forces with him and try the mountain once more via the Italian ridge. On this attempt a storm, however, soon developed and they were stuck halfway to the summit. They remained there for 26 hours in their tent before giving up. Whymper did not make another attempt for two years.

In the decisive year 1865, Whymper returned with new plans, deciding to attack the Matterhorn via its south face instead of the Italian ridge. On June 21, Whymper began his ascent with Swiss guides, but halfway up they experienced severe rockfall; although nobody was injured, they decided to give up the ascent. This was Whymper's seventh attempt.

During the following weeks, Whymper spent his time climbing other mountains in the area with his guides, before going back to Breuil on July 7. Meanwhile the Italian Alpine Club was founded and its leaders, Felice Giordano

and Quintino Sella

, established plans to conquer the Matterhorn before any non-Italian could succeed. Felice Giordano hired Carrel as guide, he feared the arrival of Whymper, now a rival, and wrote to Quintino Sella:

Just as he did two years before, Whymper asked Carrel to be his guide, but Carrel declined; he was also unsuccessful in hiring other local guides from Breuil. When Whymper discovered Giordano and Carrel's plan, he left Breuil and crossed the Theodul Pass

to Zermatt to hire local guides. He encountered Lord Francis Douglas

, a Scottish mountaineer, who also wanted to climb the Matterhorn. They arrived later in Zermatt in the Monte Rosa Hotel

, where they met two other British climbers — the Reverend Charles Hudson and his young and inexperienced companion, Douglas Robert Hadow

— who had hired the French guide Michel Croz

to try to make the first ascent. These two groups decided to join forces and try the ascent of the Hörnli ridge. They hired another two local guides, Peter Taugwalder, father and son.

Despite its appearance, Whymper wrote that the Hörnli ridge was much easier to climb than the Italian ridge:

After having camped for the night, Whymper and party started on the ridge. According to Whymper:

When the party came close to the summit, they had to leave the ridge for the north face because "[the ridge] was usually more rotten and steep, and always more difficult than the face". At this point of the ascent Whymper wrote that the less experienced Hadow "required continual assistance". Having overcome these difficulties the group finally arrived in the summit area, with Croz and Whymper reaching the top first.

Precisely at this moment, Carrel and party were approximatively 400 metres below, still dealing with the most difficult parts of the Italian ridge. When seeing his rival on the summit, Carrel and party gave up on their attempt and went back to Breuil.

After having built a cairn, Whymper and party stayed an hour on the summit. Then they began their descent of the Hörnli ridge. Croz descended first, then Hadow, Hudson and Douglas, Taugwalder father, Whymper with Taugwalder son coming last. They climbed down with great care, only one man moving at a time. Whymper wrote:

After having built a cairn, Whymper and party stayed an hour on the summit. Then they began their descent of the Hörnli ridge. Croz descended first, then Hadow, Hudson and Douglas, Taugwalder father, Whymper with Taugwalder son coming last. They climbed down with great care, only one man moving at a time. Whymper wrote:

The weight of the falling men pulled Hudson and Douglas from their holds and dragged them down the north face. Taugwalder, father and son, and Whymper were left alive when the rope linking Douglas to Taugwalder father broke. They were stunned by the accident and for a time could not move until Taugwalder son descended to enable them to advance. When they were together Whymper asked to see the broken rope and saw that it had been employed by mistake as it was the weakest and oldest of the three ropes they had brought. They frequently looked, but in vain, for traces of their fallen companions. They continued their descent, including an hour in the dark, until 9.30pm when a resting place was found. At daybreak the descent was resumed and the group finally reached Zermatt, where a search of the victims was quickly organized. The bodies of Croz, Hadow and Hudson were found on the Matterhorn Glacier, but the body of Douglas was never found. Although Taugwalder's father was accused of cutting the rope to save himself and his son, the official inquest found no proof for this.

set out to crown Whymper's victory by proving that the Italian side was not unconquerable. He was accompanied by Amé Gorret, a priest who had shared with him the first attempt on the mountain back in 1857. Jean-Baptiste Bich and Jean-Augustin Meynet completed the party. Giordano

would have joined them, but Carrel refused absolutely to take him with them; he said he would not have the strength to guide a traveller, and could neither answer for the result nor for any one's life. After hearing Sunday mass at the chapel of Breuil, the party started. Amé Gorret has described this ascent with enthusiasm: "At last we crossed the Col du Lion and set foot upon the pyramid of the Matterhorn!" On the following day, the 17th, they continued the ascent and reached Tyndall's flagstaff. "We were about to enter unknown country," wrote Gorret, "for no man had gone beyond this point." Here opinions were divided; Gorret suggested ascending by the ridge and scaling the last tower straight up. Carrel was inclined to traverse to the west of the peak, and thence go up on the Zmutt side. Naturally the wish of Carrel prevailed, for he was the leader and had not lost the habit of command, notwithstanding his recent defeat.

They made the passage of the enjambée, and traversed the west face to reach the Zmutt ridge. A false step made by one of the party and a fall of icicles from above warned them to return to the direct line of ascent, and the traverse back to the Lion ridge was one of the greatest difficulty. A falling stone wounded Gorret in the arm.

At last they reached the base of the final tower. 'We stood," wrote Gorret, "in a place that was almost comfortable. Although it was not more than two yards wide, and the slope was one of 75 percent., we gave it all kinds of pleasant names : the corridor, the gallery, the railroad, &c., &c." They imagined all difficulties were at an end; but a rock couloir, which they had hitherto not observed, lay between them and the final bit of ridge, where progress would be perfectly easy. It would have been unwise for all four to descend into the couloir, because they did not know where to fix the rope that would be needed on their return. Time pressed: it was necessary to reduce the numbers of the party; Gorret sacrificed himself, and Meynet stopped with him. Very soon afterwards Carrel and Bich were finally on the top. Meanwhile Giordano at Breuil was writing in his diary as follows: "Splendid weather; at 9.30 saw Carrel and his men on the Shoulder, after that saw nothing more of them. Then much mist about the summit. Lifted a bit about 3.30, and we saw our flag on the western summit of the Matterhorn."

, J. J. and J. P. Maquignaz was the first to traverse the summit by way of the Hörnli and Italian ridges. On August 22, 1871, while wearing a white print dress, Lucy Walker

became the first woman to reach the summit of the Matterhorn, followed a few weeks later by her rival Meta Brevoort

. The first winter ascent of the Hörnli ridge was by Vittorio Sella

with guides J. A. Carrel, J. B. Carrel and L. Carrel on March 17, 1882, and its first solo ascent was made by W. Paulcke in 1898. The first winter solo ascent of the Hörnli ridge was by G. Gervasutti in 1936.

The Zmutt ridge was first climbed by Albert F. Mummery

, Alexander Burgener, J. Petrus and A. Gentinetta on September 3, 1879. Its first solo ascent was made by Hans Pfann in 1906, and the first winter ascent was made by H. Masson and E. Petrig on March 25, 1948.

The last of the Matterhorn's four ridges to be ascended was the Furggen ridge. M. Piacenza with guides J. J. Carrel and J. Gaspard on September 9, 1911, climbed most of the ridge but bypassed the overhangs near the top to the south. Not until September 23, 1942, during the Second World War, did Alfredo Perino, along with guides Louis Carrel (nicknamed "The Little Carrel") and Giacomo Chiara, climb the complete ridge and the overhangs directly.

On August 20, 1992 Italian alpinist Hans Kammerlander and Swiss alpine guide Diego Wellig climbed the Matterhorn four times in just 23 hours and 26 minutes. The route they followed was: Zmutt ridge–summit–Hörnli ridge (descent)–Furggen ridge–summit–Lion ridge (descent)–Lion ridge–summit–Hörnli ridge (descent)–Hörnli ridge–summit–Hörnli Hut

(descent). Their itinerary has not been repeated.

and guides made the first (partial) ascent of the west face, the Matterhorn's most hidden and unknown, one hour after Mummery and party's first ascent of the Zmutt ridge on September 3, 1879. It was not until 1962 that the west face was completely climbed. The ascent was made on August 13 by Renato Daguin and Giovanni Ottin. In January 1978 seven Italian alpine guides made a successful winter climb of Daguin and Ottin's highly direct, and previously unrepeated, 1962 route. But a storm came during their ascent, bringing two meters of snow to Breuil and Zermatt, and their accomplishment turned bitter when one of the climbers died during the descent.

The north face, before it was climbed in 1931, was one of the last great big wall problems in the Alps

. To succeed on the north face, good climbing and ice-climbing technique and route-finding ability were required. Unexpectedly it was first climbed by the brothers Franz and Toni Schmid on July 31–August 1, 1931. They reached the summit at the end of the second day, after a night of bivouack. Because they had kept their plans secret, their ascent was a complete surprise. In addition, the two brothers had travelled by bicycle from Munich and after their successful ascent they cycled back home again. The first winter ascent of the north face was made by Hilti von Allmen and Paul Etter on February 3–4, 1962. Its first solo ascent was made in five hours by Dieter Marchart on July 22, 1959. Walter Bonatti

climbed the "North Face Direct" solo on February 18–22, 1965.

Ueli Steck set the record time in climbing the North Face (Schmid route) of Matterhorn in 2009 with a time just under 2 hours. he clocked in at an astounding 1 hour 56 minutes.

After Bonatti's climb, the best alpinists were still preoccupied with one last great problem: the "Zmutt Nose", an overhang lying on the right-hand side of the north face. In July 1969 two Italians, Alessandro Gogna and Leo Cerruti, attempted to solve the problem. It took them four days to figure out the unusual overhangs, avoiding however its steepest part. In July 1981 the Swiss Michel Piola and Pierre-Alain Steiner surmounted the Zmutt Nose by following a direct route, the Piola-Steiner.

The first ascent of the south face was made by E. Benedetti with guides L. Carrel and M. Bich on October 15, 1931, and the first complete ascent of the east face was made by E. Benedetti and G. Mazzotti with guides L. and L. Carrel, M. Bich and A. Gaspard on September 18–19, 1932.

Today, all ridges and faces of the Matterhorn have been ascended in all seasons, and mountain guide

s take a large number of people up the northeast Hörnli route each summer. By modern standards, the climb is fairly difficult (AD Difficulty rating)

, but not hard for skilled mountaineers according to French climbing grades. There are fixed rope

s on parts of the route to help. Still, several climbers die each year due to a number of factors including the scale of the climb and its inherent dangers, inexperience, falling rocks, and overcrowded routes.

The usual pattern of ascent is to take the Schwarzsee

cable car up from Zermatt, hike up to the Hörnli Hut

elev. 3260 m (10,695.5 ft), a large stone building at the base of the main ridge, and spend the night. The next day, climbers rise at 3:30 am so as to reach the summit and descend before the regular afternoon clouds and storms come in. The Solvay Hut

located on the ridge at 4003 m (13,133.2 ft) can be used only in a case of emergency.

Other routes on the mountain include the Italian (Lion) ridge (AD Difficulty rating), the Zmutt ridge (D Difficulty rating) and the north face route, one of the six great north faces of the Alps

(TD+ Difficulty rating).

, one of the earliest Alpine topographers and historians, was the first to mention the region around the Matterhorn in his work, De Prisca ac Vera Alpina Raethi, published in Basel in 1538. He approached the Matterhorn as a student when in his Alpine travels he reached the summit of the Theodul Pass

but he does not seem to have paid any particular attention to the mountain itself.

The Matterhorn remained unstudied for more than two centuries, until a geologist from Geneva, Horace Benedict de Saussure, travelled to the mountain, which filled him with admiration. However de Saussure was not moved to climb the mountain, and had no hope of measuring its altitude by taking a barometer to its summit. "Its precipitous sides," he wrote, "which give no hold to the very snows, are such as to afford no means of access." Yet his scientific interest was kindled by "the proud peak which rises to so vast an altitude, like a triangular obelisk, that seems to be carved by a chisel." His mind intuitively grasped the causes which gave the peak its present precipitous form: the Matterhorn was not like a perfected crystal; the centuries had laboured to destroy a great part of an ancient and much larger mountain. On his first journey de Saussure had come from Ayas to the Col des Cimes Blanches, from where the Matterhorn first comes into view; descending to Breuil, he ascended to the Theodul Pass

The Matterhorn remained unstudied for more than two centuries, until a geologist from Geneva, Horace Benedict de Saussure, travelled to the mountain, which filled him with admiration. However de Saussure was not moved to climb the mountain, and had no hope of measuring its altitude by taking a barometer to its summit. "Its precipitous sides," he wrote, "which give no hold to the very snows, are such as to afford no means of access." Yet his scientific interest was kindled by "the proud peak which rises to so vast an altitude, like a triangular obelisk, that seems to be carved by a chisel." His mind intuitively grasped the causes which gave the peak its present precipitous form: the Matterhorn was not like a perfected crystal; the centuries had laboured to destroy a great part of an ancient and much larger mountain. On his first journey de Saussure had come from Ayas to the Col des Cimes Blanches, from where the Matterhorn first comes into view; descending to Breuil, he ascended to the Theodul Pass

. On his second journey, in 1792, he came to the Valtournanche, studying and describing it; he ascended to the Theodul Pass, where he spent three days, analysing the structure of the Matterhorn, whose height he was the first to measure, and collecting stones, plants and insects. He made careful observations, from the sparse lichen that clung to the rocks to the tiny but vigorous glacier fly that fluttered over the snows and whose existence at such heights was mysterious. At night he took refuge under the tent erected near the ruins of an old fort at the top of the pass. During these days he climbed the Klein Matterhorn

(3,883 metres), which he named the Cime Brune du Breithorn.

The first inquirers began to come to the Matterhorn. There is a record of a party of Englishmen who in the summer of 1800 crossed the Great St. Bernard Pass

, a few months after the passage of Bonaparte

; they came to Aosta and thence to Valtournanche, slept at the chalets of Breuil, and traversed the Theodul Pass

, which they called Monte Rosa. The Matterhorn was to them an object of the most intense and continuous admiration.

The Matterhorn is mentioned in a guide-book to Switzerland by Johann Gottfried Ebel

, which was published in Zürich towards the end of the eighteenth century, and translated in English in 1818. The mountain appeared in it under the three names of Silvius, Matterhorn, and Mont Cervin, and was briefly described as one of the most splendid and wonderful obelisks in the Alps. On Zermatt

there was a note: "A place which may, perhaps, interest the tourist is the valley of Praborgne (Zermatt); it is bounded by huge glaciers which come right down into the valley; the village of Praborgne is fairly high, and stands at a great height above the glaciers; its climate is almost as warm as that of Italy, and plants belonging to hot countries are to be found there at considerable altitudes, above the ice."

William Brockedon

, who came to the region in 1825, considered the crossing of the Theodul Pass from Breuil to Zermatt a difficult undertaking. He gave however, expression to his enthusiasm on the summit. When he arrived exhausted on the top of the pass, he gazed "on the beautiful pyramid of the Cervin, more wonderful than aught else in sight, rising from its bed of ice to a height of 5,000 feet, a spectacle of indescribable grandeur." In this "immense natural amphitheatre, enclosed from time immemorial by snow- clad mountains and glaciers ever white, in the presence of these grand walls the mind is overwhelmed, not indeed that it is unable to contemplate the scene, but it staggers under the immensity of those objects which it contemplates."

Those who made their way up through the Valtournanche to the foot of the mountain were few in number. W. A. B. Coolidge

, a diligent collector of old and new stories of the Alps, mentions that during those years, besides Brockedon, only Hirzel-Escher of Zürich, who crossed the Theodul Pass in 1822, starting from Breuil, accompanied by a local guide. The greater number came from the Valais

up the Visp

valley to Zermatt

. In 1813, a Frenchman, Henri Maynard, climbed to the Theodul Pass and made the first ascent of the Breithorn

; he was accompanied by numerous guides, among them J. M. Couttet of Chamonix, the same man who had gone with de Saussure to the top of the Klein Matterhorn

in 1792.

The writings of these pioneers make much mention of the Matterhorn; the bare and inert rock is gradually quickened into life by men's enthusiasm. "Stronger minds," remarked Edward Whymper

, "felt the influence of the wonderful form, and men who ordinarily spoke or wrote like rational beings, when they came under its power seemed to quit their senses, and ranted and rhapsodised, losing for a time all common forms of speech."

Among the poets of the Matterhorn during these years (1834 to 1840) were Elie de Beaumont, a famous French geologist; Pierre Jean Édouard Desor

, a naturalist of Neuchatel, who went up there with a party of friends, two of whom were Louis Agassiz

and Bernhard Studer

. Christian Moritz Engelhardt, who was so filled with admiration for Zermatt and its neighbourhood that he returned there at least ten times (from 1835 to 1855), described these places in two valuable volumes, drew panoramas and maps, and collected the most minute notes on the mineralogy and botany of the region. Zermatt was at that time a quiet little village, and travellers found hospitality at the parish priest's, or at the village doctor's.

In 1841 James David Forbes

, professor of natural philosophy at the University of Edinburgh, came to see the Matterhorn. A philosopher and geologist, and an observant traveller, he continued the work of De Saussure in his journeys and his writings. He was full of admiration for the Matterhorn, calling it the most wonderful peak in the Alps, unsealed and unscalable. These words, pronounced by a man noted among all his contemporaries for his thorough knowledge of mountains, show what men's feelings then were towards the Matterhorn, and how at a time when the idea of Alpine exploration

was gaining ground in their minds, the Matterhorn stood by itself as a mountain apart, of whose conquest it was vain even to dream. And such it remained till long after this; as such it was described by John Ball

twenty years later in his celebrated guide-book. Forbes ascended the Theodul Pass in 1842, climbed the Breithorn, and came down to Breuil; as he descended from the savage scenery of the Matterhorn, the Italian landscapes of the Valtournanche seemed to him like paradise. Meanwhile Gottlieb Samuel Studer

, the geographer, together with Melchior Ulrich, was describing and mapping the topographical features of the Zermatt peaks.

Rodolphe Töpffer

, who first accompanied and guided youth to the Alps for purposes of education and amusement, began his journeys in 1832, but it is only in 1840 that he mentions the Matterhorn. Two years later Töpffer and his pupils came to Zermatt. He has described this journey of his in a chapter entitled Voyage autour du Mont Blanc jusqu'à Zermatt, here he sings a hymn of praise to the Matterhorn, comparing its form with a "huge crystal of a hundred facets, flashing varied hues, that softly reflects the light, unshaded, from the uttermost depths of the heavens". Töpffer's book was illustrated by Alexandre Calame

, his master and friend, with drawings of the Matterhorn, executed in the romantic style of the period. It is an artificial mountain, a picture corresponding rather with the exaggerated effect it produces on the astonished mind of the artist, than with the real form of the mountain.

About this time there came a man who studied the Matterhorn in its structure and form, and who sketched it and described it in all its parts with the curiosity of the artist and the insight of the scientist. This was John Ruskin

, a new and original type of philosopher and geologist, painter and poet, whom England was enabled to create during that period of radical intellectual reforms, which led the way for the highest development of her civilisation. Ruskin was the Matterhorn's poet par excellence. He went to Zermatt in 1844, and it is to be noticed as a curious fact, that the first time he saw the Matterhorn it did not please him. The mountain on its lofty pedestal in the very heart of the Alps was, perhaps, too far removed from the ideal he had formed of the mountains; but he returned, studied and dreamt for long at its feet, and at length he pronounced it "the most noble cliff in Europe." Ruskin was no mountaineer, nor a great friend to mountaineering; he drew sketches of the mountains merely as an illustration of his teaching of the beauty of natural forms, which was the object of his whole life. In his work on Modern Painters he makes continual use of the mountains as an example of beauty and an incentive to morality. The publication of Ruskin's work certainly produced a great impression at the time on educated people in England, and a wide spread desire to see the mountains.

Other men of high attainments followed, but in the years 1850 scientists and artists were about to be successed by real climbers and the passes and peaks around Zermatt were explored little by little. In the preface to the first volume of the Alpine Journal

, which appeared in 1863, the editor, Mr. H. B. George, after remarking that nearly all the highest peaks in the Alps had by then been conquered, wrote the following words, which sounded an appeal to English climbers : " While even if all other objects of interest in Switzerland should be exhausted, the Matterhorn remains (who shall say for how long?) unconquered and apparently invincible."

The traditional inaccessibility of the Matterhorn was vanquished after an expedition led by Whymper successfully reached the summit in 1865. But it ended dramatically with four men perishing on the descent. The news of the catastrophe gave rise to a universal cry of horror. Of all Alpine disasters, not one, not even of those which had a larger number of victims, ever moved men's minds as this one did. The whole of Europe talked of it; the English papers discussed it with bitter words of blame; Italian papers invented a tale of a rock detaching itself from the summit, and sweeping the helpless victims to destruction, or of a hidden crevasse opening wide its terrible jaws to swallow them. A German newspaper published an article in which Whymper was accused of cutting the rope between Douglas and Taugwalder, at the critical moment, to save his own life.

In 1890 the Federal Government was asked simultaneously by the same contractor for a concession for the Zermatt-Gornergrat railway

, and for a Zermatt-Matterhorn one. The Gornergrat railway was constructed, and has been working since 1899, but there has been no more talk of the other. The project essentially consisted of a line which went up to the Hörnli, and continued thence in a rectilinear tunnel about two kilometres long, built under the ridge, and issuing near the summit on the Zmutt side. Sixty years later in 1950, Italian engineer Count Dino Lora Totino planned a cable car on the Italian side from Breuil-Cervinia to the summit. But the Alpine Museum of Zermatt sent a protest letter with 90'000 signatures to the Italian government. The latter declared the Matterhorn a natural wonder worthy of protection and refused the concession to the engineer.

During the 20th century, the Matterhorn and the story of the first ascent in particular, inspired various artists and film producers such as Luis Trenker

and Walt Disney

.

Designed in 1908 by Emil Cardinaux, a leading poster artist of the time, the Matterhorn affiche for the Zermatt tourist office is often considered the first modern poster. It has been described as a striking example of marriage of tourism, patriotism and popular art. It served as decoration in many Swiss military hospices during the war in addition to be found in countless middle class living rooms. Since then, the Matterhorn has become a reference that still inspires graphic artists today and has been used extensively for all sort of publicity and advertising.

Pennine Alps

The Pennine Alps are a mountain range in the western part of the Alps. They are located in Switzerland and Italy...

on the border between Switzerland

Switzerland

Switzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

and Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

. Its summit is 4,478 metres (14,690 ft) high, making it one of the highest peaks in the Alps

Alps

The Alps is one of the great mountain range systems of Europe, stretching from Austria and Slovenia in the east through Italy, Switzerland, Liechtenstein and Germany to France in the west....

. The four steep faces, rising above the surrounding glaciers, face the four compass points. The mountain overlooks the town of Zermatt

Zermatt

Zermatt is a municipality in the district of Visp in the German-speaking section of the canton of Valais in Switzerland. It has a population of about 5,800 inhabitants....

in the canton of Valais

Valais

The Valais is one of the 26 cantons of Switzerland in the southwestern part of the country, around the valley of the Rhône from its headwaters to Lake Geneva, separating the Pennine Alps from the Bernese Alps. The canton is one of the drier parts of Switzerland in its central Rhône valley...

to the north-east and Breuil-Cervinia in the Aosta Valley to the south. The Theodul Pass

Theodul Pass

The Theodul Pass is a high mountain pass across the eastern Pennine Alps, connecting Zermatt in the Swiss canton of Valais and Breuil-Cervinia in the Italian region of Aosta Valley.The pass lies between the Matterhorn on the west and the Breithorn on...

, located at the eastern base of the peak, is the lowest passage between its north and south side.

The Matterhorn was the last great Alpine peak to be climbed and its first ascent

First ascent of the Matterhorn

The first ascent of the Matterhorn was made by Edward Whymper, Lord Francis Douglas, Charles Hudson, Douglas Hadow, Michel Croz, and the two Zermatt guides, Peter Taugwalder father and son on 14 July 1865. Douglas, Hudson, Hadow and Croz were killed on the descent when Hadow slipped and pulled the...

marked the end of the golden age of alpinism

Golden age of alpinism

The golden age of alpinism was the period between Alfred Wills's ascent of the Wetterhorn in 1854 and Edward Whymper's ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865, during which many major peaks in the Alps saw their first ascents....

. It was made in 1865 by a party led by Edward Whymper

Edward Whymper

Edward Whymper , was an English illustrator, climber and explorer best known for the first ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865. On the descent four members of the party were killed.-Early life:...

and ended disastrously when four of its members fell to their deaths on the descent. The north face was not climbed until 1931, and is amongst the six great north faces of the Alps

Great north faces of the Alps

In mountaineering, the six great north faces of the Alps are known for their difficulty and great height. They are:*Cima Grande di Lavaredo*Eiger*Grandes Jorasses*Matterhorn*Petit Dru*Piz Badile...

. The Matterhorn is one of the deadliest peaks in the Alps: from 1865 – when it was first climbed – to 1995, 500 alpinists died on it.

The Matterhorn has become an iconic emblem of the Swiss Alps

Swiss Alps

The Swiss Alps are the portion of the Alps mountain range that lies within Switzerland. Because of their central position within the entire Alpine range, they are also known as the Central Alps....

and the Alps

Alps

The Alps is one of the great mountain range systems of Europe, stretching from Austria and Slovenia in the east through Italy, Switzerland, Liechtenstein and Germany to France in the west....

in general. Since the end of the 19th century, when railways were built, it attracted more and more visitors and climbers. Each summer a large number of mountaineers try to climb the Matterhorn via the northeast Hörnli ridge, the most popular route to the summit.

Naming

The mountain derives its name from the GermanGerman language

German is a West Germanic language, related to and classified alongside English and Dutch. With an estimated 90 – 98 million native speakers, German is one of the world's major languages and is the most widely-spoken first language in the European Union....

words Matte, meaning "meadow", and Horn, which means "peak". The migration of the name "meadow" from the lower part of the countryside to the peak is common in the Alps. The Italian

Italian language

Italian is a Romance language spoken mainly in Europe: Italy, Switzerland, San Marino, Vatican City, by minorities in Malta, Monaco, Croatia, Slovenia, France, Libya, Eritrea, and Somalia, and by immigrant communities in the Americas and Australia...

and French

French language

French is a Romance language spoken as a first language in France, the Romandy region in Switzerland, Wallonia and Brussels in Belgium, Monaco, the regions of Quebec and Acadia in Canada, and by various communities elsewhere. Second-language speakers of French are distributed throughout many parts...

names (Cervino and Cervin) come from Mons Silvius (or Mons Sylvius) from the Latin word silva, meaning forest (with again the migration of the name from the lower part to the peak). The changing of the first letter "s" to "c" is attributed to Horace Bénédict de Saussure, who thought that the word was related to a deer (French: cerf and Italian: cervo).

In Sebastian Münster

Sebastian Münster

Sebastian Münster , was a German cartographer, cosmographer, and a Hebrew scholar.- Life :Münster was born at Ingelheim near Mainz, the son of Andreas Munster. He completed his studies at the Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen in 1518. His graduate adviser was Johannes Stöffler.He was appointed to...

's Cosmography

Cosmographia (Sebastian Münster)

The Cosmographia by Sebastian Münster from 1544 is the earliest German description of the world. It had numerous editions in different languages including Latin, French , Italian, English, and even Czech. The last German edition was published in 1628, long after his death...

, published in 1543, the name of Matter is given to the Theodul Pass

Theodul Pass

The Theodul Pass is a high mountain pass across the eastern Pennine Alps, connecting Zermatt in the Swiss canton of Valais and Breuil-Cervinia in the Italian region of Aosta Valley.The pass lies between the Matterhorn on the west and the Breithorn on...

, and this seems to be the origin of the present German name of the mountain. On Münster's topographical chart this group is marked under the names of Augstalberg ("Aosta mountain") and Mons Silvius. An hypothesis of Josias Simler (De Alpibus Commentarius, 1574) on the etymology of the name of Mons Silvius was readopted by T. G. Farinetti: "Silvius was probably a Roman leader who sojourned with his legions in the land of the Salassi and the Seduni, and perhaps crossed the Theodul Pass between these two places. This Silvius may have been that same Servius Galba whom Caesar charged with the opening up of the Alpine passes, which from that time onward traders have been wont to cross with great danger and grave difficulty. Servius Galba, in order to carry out Caesar's orders, came with his legions from Allobrogi (Savoy) to Octodurum (Martigny) in the Valais, and pitched his camp there. The passes which he had orders to open from there could be no other than the St. Bernard, the Simplon, the Theodul, and the Moro; it therefore seems likely that the name of Servius, whence Silvius and later Servin, or Cervin, was given in his honour to the famous pyramid." It is not exactly known at what period the new name of Servin, or Cervin, replaced the old, from which it seems to be derived.

The Matterhorn is also named Gran Becca by the Valdôtain

Valdôtain

The Valdôtain, or Valdotans, are an ethnic group that lives in the far northwest Aosta Valley Autonomous Region of Italy. They speak several dialects of the Franco-Provençal language ....

s and Horu by the local Walliser German speaking people.

Height

Orographic lift

Orographic lift occurs when an air mass is forced from a low elevation to a higher elevation as it moves over rising terrain. As the air mass gains altitude it quickly cools down adiabatically, which can raise the relative humidity to 100% and create clouds and, under the right conditions,...

formation with the air flowing around and creating vortices, conducting condensation of the air on the lee side.

The Matterhorn has two distinct summits

Summit (topography)

In topography, a summit is a point on a surface that is higher in elevation than all points immediately adjacent to it. Mathematically, a summit is a local maximum in elevation...

, both situated on a 100-metre-long rocky ridge: the Swiss summit (4,477.5 m) on the east and the Italian summit (4,476.4 m) on the west. Their names originated from the first ascents, not for geographic reasons, as they are both located on the border. In August 1792, the Genevan geologist and explorer Horace Bénédict de Saussure made the first measurement of the Matterhorn's height, using a 50-foot-long chain spread out on the Theodul glacier and a sextant. He calculated a height of 4,501.7 metres. In 1868 the Italian engineer Felice Giordano

Felice Giordano

Felice Giordano was an Italian engineer and geologist.Giordano was born at Turin. He had an important role in the organisation of a geological service in the Kingdom of Italy and in the foundation of the Italian Geological Society...

measured a height of 4,505 metres by means of a mercurial barometer, which he had taken up to the summit. The Dufour map, which was afterwards followed by the Italian surveyors, gave 4,482 metres, or 14,704 feet, as the height of the Swiss summit. A recent survey (1999) using Global Positioning System

Global Positioning System

The Global Positioning System is a space-based global navigation satellite system that provides location and time information in all weather, anywhere on or near the Earth, where there is an unobstructed line of sight to four or more GPS satellites...

technology has been made, allowing the height of the Matterhorn to be measured to within one centimetre accuracy, and its changes to be tracked. The result was 4477.54 metres (14,690 ft).

Geography

Pyramidal peak

A pyramidal peak, or sometimes in its most extreme form called a glacial horn, is a mountaintop that has been modified by the action of ice during glaciation and frost weathering...

with four faces facing the four compass points: the north and east faces overlook, respectively, the Zmutt

Zmutt

Zmutt is a small village in the municipality of Zermatt, Valais, Switzerland, situated at 1936 m in the Zmutt Valley west of Zermatt. The village chapel is dedicated to Saint Catherine of Alexandria, patroness of the Valais...

valley and Gornergrat

Gornergrat

The Gornergrat is a ridge of the Pennine Alps, Switzerland, overlooking the Gorner Glacier to the south. It can be reached by the Gornergratbahn rack railway from Zermatt...

ridge in Switzerland, the south face (the only one south of the Swiss-Italian border) fronts the resort town of Breuil-Cervinia, and the west face looks towards the mountain of Dent d'Hérens

Dent d'Hérens

The Dent d'Hérens is a mountain in the Pennine Alps, lying on the border between Italy and Switzerland. The mountain lies a few kilometres west of the Matterhorn.The Aosta hut is used for the normal route.-Naming:...

which straddles the border. The north and south faces meet at the summit to form a short east-west ridge.

The Matterhorn's faces are steep, and only small patches of snow and ice cling to them; regular avalanche

Avalanche

An avalanche is a sudden rapid flow of snow down a slope, occurring when either natural triggers or human activity causes a critical escalating transition from the slow equilibrium evolution of the snow pack. Typically occurring in mountainous terrain, an avalanche can mix air and water with the...

s send the snow down to accumulate on the glacier

Glacier

A glacier is a large persistent body of ice that forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. At least 0.1 km² in area and 50 m thick, but often much larger, a glacier slowly deforms and flows due to stresses induced by its weight...

s at the base of each face, the largest of which is the Zmutt Glacier

Zmutt Glacier

The Zmutt Glacier is a long glacier situated in the Pennine Alps in the canton of Valais in Switzerland. In 1973 it had an area of .-External links:*...

to the west. The Hörnli ridge of the northeast (the central ridge in the view from Zermatt) is the usual climbing route

Climbing route

A climbing route is a path by which a climber reaches the top of a mountain, rock, or ice wall. Routes can vary dramatically in difficulty and, once committed to that ascent, can be difficult to stop or return. Choice of route can be critically important...

.

Well-known faces are the east and north, visible from Zermatt. The east face is 1,000 metres high and, because it is "a long, monotonous slope of rotten rocks", presents a high risk of rockfall, making its ascent dangerous. The north face is 1,200 metres high and is one of the most dangerous north faces in the Alps, in particular for its risk of rockfall and storms. The south face is 1,350 metres high and offers many different routes. The west face, the highest at 1,400 metres, has the fewest ascent routes.

The four main ridges separating the four faces are the main climbing routes. The least difficult technical climb, the Hörnli ridge (Hörnligrat), lies between the east and north faces, facing the town of Zermatt. To its west lies the Zmutt ridge (Zmuttgrat), between the north and west faces; this is, according to Collomb, "the classic route up the mountain, its longest ridge, also the most disjointed." The Lion ridge (Cresta del Leone), lying between the south and west faces is the Italian normal route and goes across Pic Tyndall

Pic Tyndall

Pic Tyndall is a minor summit below the Matterhorn in the Pennine Alps, on the boundary between Aosta Valley and Switzerland. Because of its small prominence it was included in the enlarged list of alpine four-thousanders...

; Collomb comments, "A superb rock ridge, the shortest on the mountain, now draped with many fixed ropes, but a far superior climb compared with the Hörnli." Finally the south side is separated from the east side by the Furggen ridge (Furggengrat), according to Collomb "the hardest of the ridges [...] the ridge still has an awesome reputation but is not too difficult in good conditions by the indirect finish".

The border between Italy and Switzerland is the main Alpine watershed

Main chain of the Alps

The Alpine divide is the central line of mountains that forms the water divide of the range. Main chains of mountain ranges are traditionally designated in this way, and generally include the highest peaks of a range; the Alps are something of an unusual case in that several significant groups of...

, separating the drainage basin

Drainage basin

A drainage basin is an extent or an area of land where surface water from rain and melting snow or ice converges to a single point, usually the exit of the basin, where the waters join another waterbody, such as a river, lake, reservoir, estuary, wetland, sea, or ocean...

on the Rhone

Rhône

Rhone can refer to:* Rhone, one of the major rivers of Europe, running through Switzerland and France* Rhône Glacier, the source of the Rhone River and one of the primary contributors to Lake Geneva in the far eastern end of the canton of Valais in Switzerland...

on the north (Mediterranean Sea

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

) and the Po River

Po River

The Po |Ligurian]]: Bodincus or Bodencus) is a river that flows either or – considering the length of the Maira, a right bank tributary – eastward across northern Italy, from a spring seeping from a stony hillside at Pian del Re, a flat place at the head of the Val Po under the northwest face...

on the south (Adriatic Sea

Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan peninsula, and the system of the Apennine Mountains from that of the Dinaric Alps and adjacent ranges...

). The Theodul Pass

Theodul Pass

The Theodul Pass is a high mountain pass across the eastern Pennine Alps, connecting Zermatt in the Swiss canton of Valais and Breuil-Cervinia in the Italian region of Aosta Valley.The pass lies between the Matterhorn on the west and the Breithorn on...

, located between the Matterhorn and Klein Matterhorn

Klein Matterhorn

The Klein Matterhorn is the highest point in the Zermatt-Cervinia ski area in Switzerland, and the end point of the highest cable car in Europe...

, at 3,300 metres, is the lowest passage between the Valtournenche

Valtournenche

Valtournenche is a town and comune in the Aosta Valley region of north-western Italy.-Notable people:* Jean-Antoine Carrel , mountain climber* Jean-Joseph Maquignaz , mountain climber...

and the Mattertal

Mattertal

The Matter Valley is located in southwestern Switzerland, south of the Rhone valley in the canton of Valais. The village of Zermatt is the most important settlement of the valley, which is surrounded by many four-thousanders, including the Matterhorn.-Geography:Located in the Pennine Alps, the...

. The pass was used as a crossover and trade route for the Romans and the Romanised Celts between 100 BC and 400 AC.

While the Matterhorn is the culminating point of the Valtournenche on the south, it is only one of the many 4000 metres summits of the Mattertal valley on the north, among which the Weisshorn

Weisshorn

The Weisshorn is a mountain in the Pennine Alps, in Switzerland. With its summit, it is one of the major peaks in the Alps and overtops the nearby Matterhorn by some 30 metres. It was first climbed in 1861 from Randa by John Tyndall, accompanied by the guides J.J...

(4505 m), Dom (4545 m), Lyskamm

Lyskamm

Lyskamm is a mountain in the Pennine Alps lying on the border between Switzerland and Italy. It consists of a five-kilometre-long ridge with two distinct peaks...

(4527 m) and the second highest in the Alps: Monte Rosa

Monte Rosa

The Monte Rosa Massif is a mountain massif located in the eastern part of the Pennine Alps. It is located between Switzerland and Italy...

(4634 m). The whole range of mountains forming a crown of summits around Zermatt. The deeply glaciated region between the Matterhorn and Monte Rosa is listed in the Federal Inventory of Landscapes and Natural Monuments

Federal Inventory of Landscapes and Natural Monuments

The Federal Inventory of Landscapes and Natural Monuments in Switzerland aims to protect landscapes of national importance. The inventory is part of a 1977 Ordinance of the Swiss Federal Council implementing the Federal Law on the Protection of Nature and Cultural Heritage.The sites are of three...

.

Geology

Apart from the base of the mountain, the Matterhorn is composed of gneissGneiss

Gneiss is a common and widely distributed type of rock formed by high-grade regional metamorphic processes from pre-existing formations that were originally either igneous or sedimentary rocks.-Etymology:...

belonging to the Dent Blanche klippe

Dent Blanche klippe

The Dent Blanche nappe or Dent Blanche klippe is a geologic nappe and klippe that crops out in the Pennine Alps. The nappe is tectonostratigraphically on top of the Penninic nappes and by most researchers seen as Austroalpine....

, an isolated part of the Austroalpine nappes

Austroalpine nappes

The Austroalpine nappes are a geological nappe stack in the European Alps. The Alps contain three such stacks, of which the Austroalpine nappes are structurally on top of the other two...

, lying over the Penninic nappes

Penninic nappes

The Penninic nappes or the Penninicum are one of three nappe stacks and geological zones in which the Alps can be divided. In the western Alps the Penninic nappes are more obviously present than in the eastern Alps , where they crop out as a narrow band...

. The Austroalpine nappes are part of the Apulian plate

Apulian Plate

The Adriatic or Apulian Plate is a small tectonic plate carrying primarily continental crust that broke away from the African plate along a large transform fault in the Cretaceous period. The name Adriatic Plate is usually used when referring to the northern part of the plate...

, a small continent which broke up from Africa before the Alpine orogeny

Alpine orogeny

The Alpine orogeny is an orogenic phase in the Late Mesozoic and Tertiary that formed the mountain ranges of the Alpide belt...

. For this reason the Matterhorn has been popularized as an African mountain. The Austroalpine nappes are mostly common in the Eastern Alps.

The Swiss explorer and geologist Horace-Bénédict de Saussure

Horace-Bénédict de Saussure

200px|thumb|Portrait of Horace-Bénédict de Saussure Horace-Bénédict de Saussure was a Genevan aristocrat, physicist and Alpine traveller, often considered the founder of alpinism, and considered to be the first person to build a successful solar oven.-Life and work:Saussure was born in Conches,...

, inspired by the view of the Matterhorn, anticipated the modern theories of geology:

Formation

The formation of the Matterhorn (and the whole Alpine range) started with the break-up of the PangaeaPangaea

Pangaea, Pangæa, or Pangea is hypothesized as a supercontinent that existed during the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras about 250 million years ago, before the component continents were separated into their current configuration....

continent 200 million years ago into Laurasia

Laurasia

In paleogeography, Laurasia was the northernmost of two supercontinents that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from approximately...

(containing Europe) and Gondwana

Gondwana

In paleogeography, Gondwana , originally Gondwanaland, was the southernmost of two supercontinents that later became parts of the Pangaea supercontinent. It existed from approximately 510 to 180 million years ago . Gondwana is believed to have sutured between ca. 570 and 510 Mya,...

(containing Africa). While the rocks constituting the nearby Monte Rosa

Monte Rosa

The Monte Rosa Massif is a mountain massif located in the eastern part of the Pennine Alps. It is located between Switzerland and Italy...

remained in Laurasia, the rocks constituting the Matterhorn found themselves in Gondwana, separated by the newly formed Tethys Ocean

Tethys Ocean

The Tethys Ocean was an ocean that existed between the continents of Gondwana and Laurasia during the Mesozoic era before the opening of the Indian Ocean.-Modern theory:...

.

100 million years ago the extension of the Tethys Ocean stopped and the Apulian plate broke from Gondwana and moved toward the European continent. This resulted in the closure of the western Tethys by subduction

Subduction

In geology, subduction is the process that takes place at convergent boundaries by which one tectonic plate moves under another tectonic plate, sinking into the Earth's mantle, as the plates converge. These 3D regions of mantle downwellings are known as "Subduction Zones"...

under the Apulian plate (with the Piemont-Liguria Ocean

Piemont-Liguria Ocean

The Piemont-Liguria basin or the Piemont-Liguria Ocean was a former piece of oceanic crust that is seen as part of the Tethys Ocean...

first and Valais Ocean

Valais Ocean

The Valais Ocean is a disappeared piece of oceanic crust which was situated between the continent Europe and the microcontinent Iberia or so called Briançonnais microcontinent...

later). The subduction of the oceanic crust left traces still visible today at the base of the Matterhorn (accretionary prism). The orogeny itself began after the end of the oceanic subduction when the European continental crust collided with the Apulian continent, resulting in the formation of nappe

Nappe

In geology, a nappe is a large sheetlike body of rock that has been moved more than or 5 km from its original position. Nappes form during continental plate collisions, when folds are sheared so much that they fold back over on themselves and break apart. The resulting structure is a...

s.

The Matterhorn acquired its characteristic pyramidal shape in much more recent times as it was caused by natural erosion over the past million years. At the beginning of alpine orogeny, the Matterhorn was only a rounded mountain like a hill. Because its height is above the snowline, its flanks are covered by ice, resulting from the accumulation and compaction of snow. During the warmer period of summer, part of the ice melts and seeps into the bedrock. When it freezes again, it fractures pieces of rock because of its dilatation (freeze-thaw), forming a cirque

Cirque

Cirque may refer to:* Cirque, a geological formation* Makhtesh, an erosional landform found in the Negev desert of Israel and Sinai of Egypt*Cirque , an album by Biosphere* Cirque Corporation, a company that makes touchpads...

. Four cirques led to the shape of the mountain. Because of its recognizable shape, many other similar mountains around the world were named or nicknamed the 'Matterhorn' of their respective countries or mountain ranges.

Rocks

Most of the base of the mountain lies in the Tsaté nappe, a remnant of the Piedmont-Liguria oceanic crust (ophiolitesOphiolites

An ophiolite is a section of the Earth's oceanic crust and the underlying upper mantle that has been uplifted and exposed above sea level and often emplaced onto continental crustal rocks...

) and its sedimentary rocks. Up to 3,400 metres the mountain is composed of successive layers of ophiolites and sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rock are types of rock that are formed by the deposition of material at the Earth's surface and within bodies of water. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause mineral and/or organic particles to settle and accumulate or minerals to precipitate from a solution....

s. From 3,400 metres to the top, the rocks are gneisses from the Dent Blanche nappe (Austroalpine nappes). They are divided into the Arolla series (below 4,200 m) and the Valpelline zone (the summit). Other mountains in the region (Weisshorn, Zinalrothorn, Dent Blanche, Mont Collon) also belong to the Dent Blanche nappe.

Tourism and trekking

Since the eighteenth century the Alps have attracted more and more people and fascinated generations of explorers and climbers. The Matterhorn remained relatively little known until 1865, but the successful ascent followed by the tragic accident of the expedition led by Edward WhymperEdward Whymper

Edward Whymper , was an English illustrator, climber and explorer best known for the first ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865. On the descent four members of the party were killed.-Early life:...

caused a rush on the mountains surrounding Zermatt

Zermatt

Zermatt is a municipality in the district of Visp in the German-speaking section of the canton of Valais in Switzerland. It has a population of about 5,800 inhabitants....

.

The construction of the railway linking the village of Zermatt from the town of Visp

Visp

Visp is the capital of the district of Visp in the canton of Valais in Switzerland.-Geography:Visp has an area, , of . Of this area, 17.0% is used for agricultural purposes, while 59.7% is forested...

started in 1888. The first train reached Zermatt on July 18, 1891 and the entire line was electrified in 1930. Since 1930 the village is directly connected to St. Moritz

St. Moritz

St. Moritz is a resort town in the Engadine valley in Switzerland. It is a municipality in the district of Maloja in the Swiss canton of Graubünden...

by the Glacier Express

Glacier Express

The Glacier Express is an express train connecting railway stations of the two major mountain resorts of St. Moritz and Zermatt in the Swiss Alps. The train is operated jointly by the Matterhorn Gotthard Bahn and Rhaetian Railway...

panoramic train. However there is no connection with the village of Breuil-Cervinia

Cervinia

Breuil-Cervinia is an alpine resort in the Valle d'Aosta region of northwest Italy...

on the Italian side. Travellers have to hire mountain guides to cross the 3,300 metres high glaciated Theodul Pass

Theodul Pass

The Theodul Pass is a high mountain pass across the eastern Pennine Alps, connecting Zermatt in the Swiss canton of Valais and Breuil-Cervinia in the Italian region of Aosta Valley.The pass lies between the Matterhorn on the west and the Breithorn on...

, separating the two resorts. The town of Zermatt remains completely free of internal combustion vehicles and can be reached by train only. (Electric vehicles are used locally).

Rail and cable-car facilities have been built to make some of the summits in the area more accessible. The Gornergrat

Gornergrat

The Gornergrat is a ridge of the Pennine Alps, Switzerland, overlooking the Gorner Glacier to the south. It can be reached by the Gornergratbahn rack railway from Zermatt...

railway, reaching a record altitude of 3,100 metres, was inaugurated in 1898. Areas served by cable car are the Unterrothorn

Unterrothorn

The Unterrothon or is a mountain in the Pennine Alps above Zermatt. The summit can be reached by cable car via Sunnegga and Blauherd. The Rothorn paradise is one of the main ski areas located around Zermatt....

and the Klein Matterhorn

Klein Matterhorn

The Klein Matterhorn is the highest point in the Zermatt-Cervinia ski area in Switzerland, and the end point of the highest cable car in Europe...

(Little Matterhorn) (3,883 m, highest transportation system in Europe). The Hörnli Hut

Hörnli Hut

The Hörnli Hut is a mountain hut located at the foot of the north-eastern ridge of the Matterhorn. It is situated at above sea level, a few kilometers south-west of the town of Zermatt in the canton of Valais in Switzerland. It was built by the Swiss Alpine Club in 1880...

(3,260 m), which is the start of the normal route via the Hörnli ridge, is easily accessible from Schwarzsee

Schwarzsee (Zermatt)

Schwarzsee is a lake at Zermatt in the canton of Valais, Switzerland. It is located below Matterhorn at an elevation of 2,552 m....

(2,600 m) and is also frequented by hikers. Both resorts of Zermatt and Cervinia function as ski resort all year round and are connected by skilifts over the Theodul Pass. A cable car running from Testa Grigia to Klein Matterhorn is currently planned for 2014. It will finally provide a link between the Swiss and Italian side of the Matterhorn.

The Matterhorn Museum

Matterhorn Museum

The Matterhorn Museum in Zermatt is a cultural-natural museum whose main theme is the Matterhorn. The museum is in the form of a reconstituted mountain village consisting of 14 houses , and relates the history and development of tourism in the Zermatt area, including the story of the first ascent...

(Zermatt) relates the general history of the region from alpinism to tourism. In the museum, which is in the form of a reconstituted mountain village, the visitors can relive the first and tragic ascent of the Matterhorn and see the objects having belonged to the protagonists.

The Tour of the Matterhorn can be effected by trekkers in about 10 days. Considered by some as one of the most beautiful treks in the Alps, it follows many ancient trails that have linked the Swiss and Italian valleys for centuries. The circuit includes alpine meadows, balcony trails, larch forests and glacial crossings. It connects six valleys embracing three different cultures: the German speaking high Valais, the French speaking central Valais and the Italian speaking Val d'Aosta. Good conditions are necessary to circumnavigate the peak. After reaching Zinal

Zinal

Zinal is a village located in the municipality of Anniviers in the canton of Valais in Switzerland. It lies at an altitude of 1,675 metres in the Swiss Alps in the Val d'Anniviers, a valley running from the Zinal Glacier, north of Dent Blanche to the village of Ayer...

by the Augstbord and Meiden passes, the trekker crosses the Torrent before arriving at Arolla

Arolla

Arolla is a village in the municipality of Evolène in the canton of Valais in Switzerland.It is situated at the end of the Val d'Hérens south of Sion at 1998m altitude in the Pennine Alps...

. Then the Col Collon

Col Collon

Col Collon is a high mountain pass across the central Pennine Alps, connecting Arolla in the Swiss canton of Valais to Bionaz in the Italian region of Aosta Valley....

must be crossed on the road to Prarayer and another one to Breuil-Cervinia and back to Zermatt via the Theodul. In total, seven passes between 2,800 and 3,300 metres must be crossed on a relatively difficult terrain.

Climbing history

Alps

The Alps is one of the great mountain range systems of Europe, stretching from Austria and Slovenia in the east through Italy, Switzerland, Liechtenstein and Germany to France in the west....

mountains to be ascended, not because of its technical difficulty, but because of the fear it inspired in early mountaineers

Mountaineering

Mountaineering or mountain climbing is the sport, hobby or profession of hiking, skiing, and climbing mountains. While mountaineering began as attempts to reach the highest point of unclimbed mountains it has branched into specialisations that address different aspects of the mountain and consists...

. The first serious attempts began around 1857, mostly from the Italian side; but despite appearances, the southern routes are harder, and parties repeatedly found themselves having to turn back. However, on July 14, 1865, in what is considered the last ascent of the golden age of alpinism

Golden age of alpinism

The golden age of alpinism was the period between Alfred Wills's ascent of the Wetterhorn in 1854 and Edward Whymper's ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865, during which many major peaks in the Alps saw their first ascents....

, the English

England