Meiji period

Encyclopedia

The , also known as the Meiji era, is a Japanese era which extended from September 1868 through July 1912. This period represents the first half of the Empire of Japan

.

On 3 February 1867, 15-year-old prince Mutsuhito

succeeded his father, Emperor Kōmei

, to the Chrysanthemum Throne

as the 122nd emperor.

Imperial restoration

occurred the next year on 3 January 1868 with the formation of the new government. The Tokugawa Shogunate

was overthrown with the fall of Edo

in the summer of 1868, and a new era called Meiji, meaning "enlightened rule", proclaimed.

The first reform was the promulgation of the Five Charter Oath

in 1868, a general statement of the aims of the Meiji leaders

to boost morale and win financial support for the new government

. Its five provisions consisted of

Implicit in the Charter Oath was an end to exclusive political rule by the bakufu

and a move toward more democratic participation in government. To implement the Charter Oath, an eleven-article constitution was drawn up. Besides providing for a new Council of State, legislative bodies, and systems of ranks for nobles and officials, it limited office tenure to four years, allowed public balloting, provided for a new taxation system, and ordered new local administrative rules.

The Meiji government assured the foreign powers that it would follow the old treaties negotiated by the bakufu and announced that it would act in accordance with international law. Mutsuhito, who was to reign until 1912, selected a new reign title—Meiji, or Enlightened Rule—to mark the beginning of a new era in Japanese history. To further dramatize the new order, the capital was relocated from Kyoto

, where it had been situated since 794, to Tokyo (Eastern Capital), the new name for Edo

. In a move critical for the consolidation of the new regime, most daimyo

voluntarily surrendered their land and census records to the emperor in the Abolition of the Han system

, symbolizing that the land and people were under the emperor's jurisdiction. Confirmed in their hereditary positions, the daimyo became governors, and the central government assumed their administrative expenses and paid samurai

Confirmed in their hereditary positions, the daimyo became governors, and the central government assumed their administrative expenses and paid samurai

stipends. The han were replaced with prefectures

in 1871, and authority continued to flow to the national government. Officials from the favored former han, such as Satsuma, Chōshū, Tosa

, and Hizen, staffed the new ministries. Formerly out-of-favor court nobles and lower-ranking but more radical samurai replaced bakufu appointees, daimyo, and old court nobles as a new ruling class appeared.

Inasmuch as the Meiji Restoration had sought to return the emperor to a preeminent position, efforts were made to establish a Shinto

-oriented state much like the state of 1,000 years earlier. Since Shinto and Buddhism had molded into a syncretic

belief in the last one-thousand years, a new State Shinto

had to be constructed for the purpose. The Office of Shinto Worship was established, ranking even above the Council of State in importance. The kokutai

ideas of the Mito school were embraced, and the divine ancestry of the imperial house was emphasized. The government supported Shinto teachers, a small but important move. Although the Office of Shinto Worship was demoted in 1872, by 1877 the Home Ministry

controlled all Shinto shrines and certain Shinto sects were given state recognition. Shinto was released from Buddhist administration and its properties restored. Although Buddhism suffered from state sponsorship of Shinto, it had its own resurgence. Christianity was also legalized, and Confucianism remained an important ethical doctrine. Increasingly, however, Japanese thinkers identified with Western ideology and methods.

A major proponent of representative government was Itagaki Taisuke

A major proponent of representative government was Itagaki Taisuke

(1837–1919), a powerful Tosa

leader who had resigned from the Council of State over the Korean affair

in 1873. Itagaki sought peaceful rather than rebellious means to gain a voice in government. He started a school and a movement aimed at establishing a constitutional monarchy

and a legislative assembly

. Such movements were called The Freedom and People's Rights Movement

. Itagaki and others wrote the Tosa Memorial in 1874 criticizing the unbridled power of the oligarchy and calling for the immediate establishment of representative government.

Between 1871 and 1873, a series of land and tax laws

were enacted as the basis for modern fiscal policy. Private ownership was legalized, deeds were issued, and lands were assessed at fair market value with taxes paid in cash rather than in kind as in pre-Meiji days and at slightly lower rates.

Dissatisfied with the pace of reform after having rejoined the Council of State

in 1875, Itagaki organized his followers and other democratic proponents into the nationwide Aikokusha

(Society of Patriots) to push for representative government in 1878. In 1881, in an action for which he is best known, Itagaki helped found the Jiyuto

(Liberal Party), which favored French political doctrines.

In 1882 Okuma Shigenobu

established the Rikken Kaishintō

(Constitutional Progressive Party), which called for a British-style constitutional democracy. In response, government bureaucrats, local government officials, and other conservatives established the Rikken Teiseitō

(Imperial Rule Party), a pro-government party, in 1882. Numerous political demonstrations followed, some of them violent, resulting in further government restrictions. The restrictions hindered the political parties and led to divisions within and among them. The Jiyuto, which had opposed the Kaishinto, was disbanded in 1884, and Okuma resigned as Kaishinto president.

Government leaders, long preoccupied with violent threats to stability and the serious leadership split over the Korean affair, generally agreed that constitutional government should someday be established. The Chōshū

leader Kido Takayoshi

had favored a constitutional form of government since before 1874, and several proposals for constitutional guarantees had been drafted. The oligarchy, however, while acknowledging the realities of political pressure, was determined to keep control. Thus, modest steps were taken.

The Osaka Conference in 1875 resulted in the reorganization of government with an independent judiciary and an appointed Chamber of Elders (Genrōin) tasked with reviewing proposals for a legislature. The emperor declared that "constitutional government shall be established in gradual stages" as he ordered the Council of Elders to draft a constitution.

Three years later, the Conference of Prefectural Governors established elected prefectural assemblies. Although limited in their authority, these assemblies represented a move in the direction of representative government at the national level, and by 1880 assemblies also had been formed in villages and towns. In 1880 delegates from twenty-four prefectures held a national convention to establish the Kokkai Kisei Domei (League for Establishing a National Assembly).

Although the government was not opposed to parliamentary rule, confronted with the drive for "people's rights", it continued to try to control the political situation. New laws in 1875 prohibited press criticism of the government or discussion of national laws. The Public Assembly Law (1880) severely limited public gatherings by disallowing attendance by civil servants and requiring police permission for all meetings.

Within the ruling circle, however, and despite the conservative approach of the leadership, Okuma continued as a lone advocate of British-style government, a government with political parties and a cabinet organized by the majority party, answerable to the national assembly. He called for elections to be held by 1882 and for a national assembly to be convened by 1883; in doing so, he precipitated a political crisis that ended with an 1881 imperial rescript declaring the establishment of a national assembly in 1890 and dismissing Okuma.

Rejecting the British model, Iwakura

and other conservatives borrowed heavily from the Prussian constitutional system

. One of the Meiji oligarchy, Itō Hirobumi

(1841–1909), a Chōshū native long involved in government affairs, was charged with drafting Japan's constitution. He led a Constitutional Study Mission abroad in 1882, spending most of his time in Germany. He rejected the United States Constitution

as "too liberal" and the British system as too unwieldy and having a parliament with too much control over the monarchy; the French and Spanish models were rejected as tending toward despotism.

Ito was put in charge of the new Bureau for Investigation of Constitutional Systems in 1884, and the Council of State was replaced in 1885 with a cabinet headed by Ito as prime minister. The positions of chancellor, minister of the left, and minister of the right, which had existed since the 7th century as advisory positions to the emperor, were all abolished. In their place, the Privy Council was established in 1888 to evaluate the forthcoming constitution and to advise the emperor.

To further strengthen the authority of the state, the Supreme War Council was established under the leadership of Yamagata Aritomo

(1838–1922), a Chōshū native who has been credited with the founding of the modern Japanese army and was to become the first constitutional prime minister. The Supreme War Council developed a German-style general staff system with a chief of staff who had direct access to the emperor and who could operate independently of the army

minister and civilian officials.

When finally granted by the emperor as a sign of his sharing his authority and giving rights and liberties to his subjects, the 1889 Constitution of the Empire of Japan

(the Meiji Constitution

) provided for the Imperial Diet (Teikoku Gikai), composed of a popularly elected House of Representatives with a very limited franchise of male citizens who were over 25 years of age and paid 15 yen in national taxes, about 1 % of the population, and the House of Peers

, composed of nobility and imperial appointees; and a cabinet responsible to the emperor and independent of the legislature. The Diet could approve government legislation and initiate laws, make representations to the government, and submit petitions to the emperor. Nevertheless, in spite of these institutional changes, sovereignty still resided in the emperor on the basis of his divine ancestry.

The new constitution specified a form of government that was still authoritarian in character, with the emperor holding the ultimate power and only minimal concessions made to popular rights and parliamentary mechanisms. Party participation was recognized as part of the political process. The Meiji Constitution was to last as the fundamental law until 1947.

In the early years of constitutional government, the strengths and weaknesses of the Meiji Constitution were revealed. A small clique of Satsuma and Chōshū elite continued to rule Japan, becoming institutionalized as an extra-constitutional body of genro

(elder statesmen). Collectively, the genro made decisions reserved for the emperor, and the genro, not the emperor, controlled the government politically.

Throughout the period, however, political problems were usually solved through compromise, and political parties gradually increased their power over the government and held an ever larger role in the political process as a result. Between 1891 and 1895, Ito served as prime minister with a cabinet composed mostly of genro who wanted to establish a government party to control the House of Representatives. Although not fully realized, the trend toward party politics was well established.

, count

, viscount

, and baron

.

It was at this time that the Ee ja nai ka

movement, a spontaneous outbreak of ecstatic behaviour, took place.

In 1885, the intellectual Yukichi Fukuzawa wrote the influential essay Leaving Asia

, arguing that Japan should orient itself at the "civilized countries of the West", leaving behind the "hopelessly backward" Asian neighbors, namely Korea

and China. This essay certainly contributed to the economic and technological rise of Japan in the Meiji period but it may also have laid the foundations for later Japanese colonialism

in the region.

in Japan occurred during the Meiji period.

There were at least two reasons for the speed of Japan's modernization: the employment of over 3,000 foreign experts (called o-yatoi gaikokujin

or 'hired foreigners') in a variety of specialist fields such as teaching English, science, engineering, the army and navy etc.; and the dispatch of many Japanese students overseas to Europe and America, based on the fifth and last article of the Charter Oath of 1868: 'Knowledge shall be sought throughout the world so as to strengthen the foundations of Imperial rule.' This process of modernization was closely monitored and heavily subsidized by the Meiji government, enhancing the power of the great zaibatsu

firms such as Mitsui

and Mitsubishi

.

Hand in hand, the zaibatsu and government guided the nation, borrowing technology from the West. Japan gradually took control of much of Asia's market for manufactured goods, beginning with textiles. The economic structure became very mercantilistic, importing raw materials and exporting finished products — a reflection of Japan's relative poverty in raw materials.

Japan emerged from the Tokugawa

–Tennō

(Keiō

-Meiji) transition in 1868 as the first Asian industrialized nation. Domestic commercial activities and limited foreign trade had met the demands for material culture until the Keiō period, but the modernized Meiji period had radically different requirements. From the onset, the Meiji rulers embraced the concept of a market economy and adopted British and North American forms of free enterprise capitalism. The private sector — in a nation with an abundance of aggressive entrepreneurs — welcomed such change.

Economic reforms included a unified modern currency based on the yen, banking, commercial and tax laws, stock exchanges, and a communications network. Establishment of a modern institutional framework conducive to an advanced capitalist economy took time but was completed by the 1890s. By this time, the government had largely relinquished direct control of the modernization process, primarily for budgetary reasons.

Many of the former daimyo, whose pensions had been paid in a lump sum, benefited greatly through investments they made in emerging industries. Those who had been informally involved in foreign trade before the Meiji Restoration also flourished. Old bakufu-serving firms that clung to their traditional ways failed in the new business environment.

The government was initially involved in economic modernization, providing a number of "model factories" to facilitate the transition to the modern period. After the first twenty years of the Meiji period, the industrial economy expanded rapidly until about 1920 with inputs of advanced Western technology and large private investments. Stimulated by wars and through cautious economic planning, Japan emerged from World War I as a major industrial nation.

It wasn't until the beginning of the Meiji Era in 1868 that the Japanese government began taking modernization seriously. In 1868, the Japanese government established the Tokyo Arsenal. This arsenal was responsible for the development and manufacture of small arms and associated ammunition (GlobalSecurity.org, 2008). The same year, Masujiro Omura established Japan's first ever military academy in Kyoto. Omura further proposed military billets be filled by all classes of people including farmers and merchants. The shogun class, not happy with Omura's views on conscription, assassinated him the following year (Shinsengumihq.com, n.d.).

In 1870, Japan expanded its military production base by opening another arsenal in Osaka. The Osaka Arsenal was responsible for the production of machine guns and ammunition (National Diet Library, 2008). Also, four gunpowder facilities were also opened at this site. Japan's production capacity gradually improved.

In 1872, Yamagata Aritomo and Saigo Tsugumichi, both new field marshals, founded the Corps of the Imperial Guards. This corps was composed of the warrior classes from the Tosa, Satsuma, and Chusho clans (GlobalSecurity.org, 2008). Also, in the same year, the hyobusho (war office) was replaced with a War Department and a Naval Department. The samurai class suffered great disappointment the following years, when in January the Conscription Law of 1873 was passed. This law required every able bodied male Japanese citizen, regardless of class, to serve a mandatory term of three years with the first reserves and two additional years with the second reserves (GlobalSecurity.org, 2008). This monumental law, signifying the beginning of the end for the samurai class, initially met resistance from both the peasant and warrior alike. The peasant class interpreted the term for military service, ketsu-eki (blood tax) literally, and attempted to avoid service by any means necessary. Avoidance methods included maiming, self-mutilation, and local uprisings (Kublin, 1949, p 32). The samurai were generally resentful of the new, western-style military and at first, refused to stand in formation with the lowly peasant class (GlobalSecurity.org, 2008).

In conjunction with the new conscription law, the Japanese government began modeling their ground forces after the French military. Indeed, the new Japanese army utilized the same rank structure as the French (Kublin, 1949, p 31). The enlisted corps ranks were: private, noncommissioned officers, and officers. The private classes were: joto-hei or upper soldier, itto-sottsu or first-class soldier, and nito-sotsu or second-class soldier. The noncommissioned officer class ranks were: gocho or corporal, gunso or sergeant, socho or sergeant major, and tokumu-socho or special sergeant major. Finally, the officer class is made up of: shoi or second lieutenant, chui or first lieutenant, tai or captain, shosa or major, chusa or lieutenant colonel, taisa or colonel, shosho or major general, chujo or lieutenant general, taisho or general, and gensui or field marshal (GlobalSecurity.org, 2008). The French government also contributed greatly to the training of Japanese officers. Many were employed at the military academy in Kyoto, and many more still were feverishly translating French field manuals for use in the Japanese ranks (GlobalSecuirty.org, 2008).

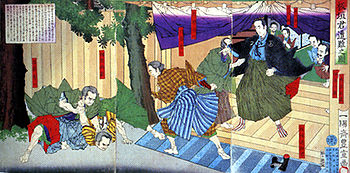

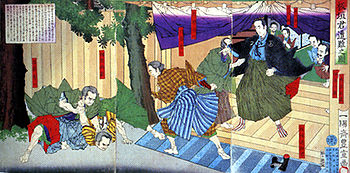

Despite the Conscription Law of 1873, and all the reforms and progress, the new Japanese army was still untested. That all changed in 1877, when Takamori Saigo, led the last rebellion of the samurai in Kyūshū. In February 1877, Saigo left Kagoshima with a small contingent of soldiers on a journey to Tokyo. Kumamoto castle was the site of the first major engagement as garrisoned forces fired on Saigo's army as they attempted to force their way into the castle. Rather than leave an enemy behind him, Saigo laid siege to the castle. Two days later, Saigo's rebels, while attempting to block a mountain pass encountered advanced elements of the national army enroute to reinforce Kumamoto castle. After a short battle, both sides withdrew to reconstitute their forces . A few weeks later the national army engaged Saigo's rebels in a frontal assault at what is now called the Battle of Tabaruzuka . During this eight day battle, Saigo's nearly ten thousand strong army battled hand-to-hand the equally matched national army. Both sides suffered nearly four thousand casualties during this engagement . Due to conscription however, the Japanese army was able to reconstitute its forces while Saigo's was not. Later, forces loyal to the Emperor broke through rebel lines and managed to end the siege on Kumamoto castle

after fifty-four days . Saigo's troops fled north, pursued by the national army. The national army caught up with Saigo at Mt. Enodake. Saigo's army was outnumbered seven to one prompting a mass surrender of many samurai .The remaining five hundred samurai loyal to Saigo escaped, travelling south to Kagoshima. The rebellion ended on September 24, 1877 following the final engagement with Imperial forces which resulted in deaths of the remaining forty samurai and Takamori Saigo himself, who, having suffered a fatal bullet wound in the abdomen, was honourably beheaded by his retainer .The army's victory validated the current course of the modernization of the Japanese army as well as ended the era of the samurai.

, and thus its isolation, the latter found itself defenseless against military pressures and economic exploitation by the Western powers. For Japan to emerge from the feudal period, it had to avoid the colonial fate of other Asian countries by establishing genuine national independence and equality. Japan released the Chinese coolies from a western ship

in 1872, after which the Qing Imperial Government China

gave thanks to Japan.

Following her defeat of China in Korea in the Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), Japan broke through as an international power with a victory against Russia in Manchuria

(north-eastern China) in the Russo-Japanese War

of 1904–1905. Allied with Britain since the Anglo-Japanese Alliance

signed in London on January 30, 1902, Japan joined the Allies in World War I, seizing German-held territory in China and the Pacific in the process, but otherwise remained largely out of the conflict.

After the war, a weakened Europe left a greater share in international markets to the U.S. and Japan, which emerged greatly strengthened. Japanese competition made great inroads into hitherto European-dominated markets in Asia, not only in China, but even in European colonies like India and Indonesia

, reflecting the development of the Meiji era.

in this period was Ernest Mason Satow

, resident in Japan 1862–83 and 1895–1900.

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan is the name of the state of Japan that existed from the Meiji Restoration on 3 January 1868 to the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of...

.

Meiji Restoration and the emperor

On 3 February 1867, 15-year-old prince Mutsuhito

Emperor Meiji

The or was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, reigning from 3 February 1867 until his death...

succeeded his father, Emperor Kōmei

Emperor Komei

was the 121st emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Kōmei's reign spanned the years from 1846 through 1867.-Genealogy:Before Kōmei's accession to the Chrysanthemum Throne, his personal name was ;, his title was ....

, to the Chrysanthemum Throne

Chrysanthemum Throne

The is the English term used to identify the throne of the Emperor of Japan. The term can refer to very specific seating, such as the takamikura throne in the Shishin-den at Kyoto Imperial Palace....

as the 122nd emperor.

Imperial restoration

Meiji Restoration

The , also known as the Meiji Ishin, Revolution, Reform or Renewal, was a chain of events that restored imperial rule to Japan in 1868...

occurred the next year on 3 January 1868 with the formation of the new government. The Tokugawa Shogunate

Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the and the , was a feudal regime of Japan established by Tokugawa Ieyasu and ruled by the shoguns of the Tokugawa family. This period is known as the Edo period and gets its name from the capital city, Edo, which is now called Tokyo, after the name was...

was overthrown with the fall of Edo

Fall of Edo

The took place between May and July 1868, when the Japanese capital of Edo , theretofore controlled by the Tokugawa Shogunate, fell to forces favorable to the restoration of Emperor Meiji during the Boshin war....

in the summer of 1868, and a new era called Meiji, meaning "enlightened rule", proclaimed.

The first reform was the promulgation of the Five Charter Oath

Five Charter Oath

The was promulgated at the enthronement of Emperor Meiji of Japan on 7 April 1868. The Oath outlined the main aims and the course of action to be followed during Emperor Meiji's reign, setting the legal stage for Japan's modernization...

in 1868, a general statement of the aims of the Meiji leaders

Meiji oligarchy

The Meiji oligarchy was the name used to describe the new ruling class of Meiji period Japan. In Japanese, the Meiji oligarchy is called the ....

to boost morale and win financial support for the new government

Government of Meiji Japan

The Government of Meiji Japan was the government which was formed by politicians of the Satsuma Domain, Chōshū Domain and Tenno. The Meiji government was the early government of the Empire of Japan....

. Its five provisions consisted of

- Establishment of deliberative assemblies

- Involvement of all classes in carrying out state affairs

- The revocation of sumptuary laws and class restrictions on employment

- Replacement of "evil customs" with the "just laws of nature" and

- An international search for knowledge to strengthen the foundations of imperial rule.

Implicit in the Charter Oath was an end to exclusive political rule by the bakufu

Shogun

A was one of the hereditary military dictators of Japan from 1192 to 1867. In this period, the shoguns, or their shikken regents , were the de facto rulers of Japan though they were nominally appointed by the emperor...

and a move toward more democratic participation in government. To implement the Charter Oath, an eleven-article constitution was drawn up. Besides providing for a new Council of State, legislative bodies, and systems of ranks for nobles and officials, it limited office tenure to four years, allowed public balloting, provided for a new taxation system, and ordered new local administrative rules.

The Meiji government assured the foreign powers that it would follow the old treaties negotiated by the bakufu and announced that it would act in accordance with international law. Mutsuhito, who was to reign until 1912, selected a new reign title—Meiji, or Enlightened Rule—to mark the beginning of a new era in Japanese history. To further dramatize the new order, the capital was relocated from Kyoto

Kyoto

is a city in the central part of the island of Honshū, Japan. It has a population close to 1.5 million. Formerly the imperial capital of Japan, it is now the capital of Kyoto Prefecture, as well as a major part of the Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto metropolitan area.-History:...

, where it had been situated since 794, to Tokyo (Eastern Capital), the new name for Edo

Edo

, also romanized as Yedo or Yeddo, is the former name of the Japanese capital Tokyo, and was the seat of power for the Tokugawa shogunate which ruled Japan from 1603 to 1868...

. In a move critical for the consolidation of the new regime, most daimyo

Daimyo

is a generic term referring to the powerful territorial lords in pre-modern Japan who ruled most of the country from their vast, hereditary land holdings...

voluntarily surrendered their land and census records to the emperor in the Abolition of the Han system

Abolition of the han system

The was an act, in 1871, of the new Meiji government of the Empire of Japan to replace the traditional feudal domain system and to introduce centralized government authority . This process marked the culmination of the Meiji Restoration in that all daimyo were required to return their authority...

, symbolizing that the land and people were under the emperor's jurisdiction.

Samurai

is the term for the military nobility of pre-industrial Japan. According to translator William Scott Wilson: "In Chinese, the character 侍 was originally a verb meaning to wait upon or accompany a person in the upper ranks of society, and this is also true of the original term in Japanese, saburau...

stipends. The han were replaced with prefectures

Prefectures of Japan

The prefectures of Japan are the country's 47 subnational jurisdictions: one "metropolis" , Tokyo; one "circuit" , Hokkaidō; two urban prefectures , Osaka and Kyoto; and 43 other prefectures . In Japanese, they are commonly referred to as...

in 1871, and authority continued to flow to the national government. Officials from the favored former han, such as Satsuma, Chōshū, Tosa

Tosa Domain

The was a feudal domain in Tosa Province of Japan during the Edo period. Its official name is . Some from the domain played important roles in events in the late Tokugawa shogunate...

, and Hizen, staffed the new ministries. Formerly out-of-favor court nobles and lower-ranking but more radical samurai replaced bakufu appointees, daimyo, and old court nobles as a new ruling class appeared.

Inasmuch as the Meiji Restoration had sought to return the emperor to a preeminent position, efforts were made to establish a Shinto

Shinto

or Shintoism, also kami-no-michi, is the indigenous spirituality of Japan and the Japanese people. It is a set of practices, to be carried out diligently, to establish a connection between present day Japan and its ancient past. Shinto practices were first recorded and codified in the written...

-oriented state much like the state of 1,000 years earlier. Since Shinto and Buddhism had molded into a syncretic

Syncretism

Syncretism is the combining of different beliefs, often while melding practices of various schools of thought. The term means "combining", but see below for the origin of the word...

belief in the last one-thousand years, a new State Shinto

State Shinto

has been called the state religion of the Empire of Japan, although it did not exist as a single institution and no "Shintō" was ever declared a state religion...

had to be constructed for the purpose. The Office of Shinto Worship was established, ranking even above the Council of State in importance. The kokutai

Kokutai

Kokutai is a politically loaded word in the Japanese language, translatable as "sovereign", "national identity; national essence; national character" or "national polity; body politic; national entity; basis for the Emperor's sovereignty; Japanese constitution". "Sovereign" is perhaps the most...

ideas of the Mito school were embraced, and the divine ancestry of the imperial house was emphasized. The government supported Shinto teachers, a small but important move. Although the Office of Shinto Worship was demoted in 1872, by 1877 the Home Ministry

Home Ministry (Japan)

The ' was a Cabinet-level ministry established under the Meiji Constitution that managed the internal affairs of Empire of Japan from 1873-1947...

controlled all Shinto shrines and certain Shinto sects were given state recognition. Shinto was released from Buddhist administration and its properties restored. Although Buddhism suffered from state sponsorship of Shinto, it had its own resurgence. Christianity was also legalized, and Confucianism remained an important ethical doctrine. Increasingly, however, Japanese thinkers identified with Western ideology and methods.

Politics

Itagaki Taisuke

Count was a Japanese politician and leader of the , which evolved into Japan's first political party.- Early life :Itagaki Taisuke was born into a middle-ranking samurai family in Tosa Domain, , After studies in Kōchi and in Edo, he was appointed as sobayonin to Tosa daimyo Yamauchi Toyoshige,...

(1837–1919), a powerful Tosa

Tosa Province

is the name of a former province of Japan in the area that is today Kōchi Prefecture on Shikoku. Tosa was bordered by Iyo and Awa Provinces. It was sometimes called .-History:The ancient capital was near modern Nankoku...

leader who had resigned from the Council of State over the Korean affair

Seikanron

The Seikanron debate was a major political conflagration which occurred in Japan in 1873....

in 1873. Itagaki sought peaceful rather than rebellious means to gain a voice in government. He started a school and a movement aimed at establishing a constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy is a form of government in which a monarch acts as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, whether it be a written, uncodified or blended constitution...

and a legislative assembly

Legislative Assembly

Legislative Assembly is the name given in some countries to either a legislature, or to one of its branch.The name is used by a number of member-states of the Commonwealth of Nations, as well as a number of Latin American countries....

. Such movements were called The Freedom and People's Rights Movement

Freedom and People's Rights Movement

The was a Japanese political and social movement for democracy in 1880s....

. Itagaki and others wrote the Tosa Memorial in 1874 criticizing the unbridled power of the oligarchy and calling for the immediate establishment of representative government.

Between 1871 and 1873, a series of land and tax laws

Land Tax Reform (Japan 1873)

The Japanese Land Tax Reform of 1873, or was started by the Meiji Government in 1873, or the 6th year of the Meiji era. It was a major restructuring of the previous land taxation system, and established the right of private land ownership in Japan for the first time.-Previous land taxation...

were enacted as the basis for modern fiscal policy. Private ownership was legalized, deeds were issued, and lands were assessed at fair market value with taxes paid in cash rather than in kind as in pre-Meiji days and at slightly lower rates.

Dissatisfied with the pace of reform after having rejoined the Council of State

Council of State

The Council of State is a unique governmental body in a country or subdivision thereoff, though its nature may range from the formal name for the cabinet to a non-executive advisory body surrounding a head of state. It is sometimes regarded as the equivalent of a privy council.-Modern:*Belgian...

in 1875, Itagaki organized his followers and other democratic proponents into the nationwide Aikokusha

Aikokusha

The ' was a political party in Meiji period Japan.The Aikokusha was formed in February 1875 by Itagaki Taisuke, as part a liberal political federation to associate his Risshisha with the Freedom and People's Rights Movement...

(Society of Patriots) to push for representative government in 1878. In 1881, in an action for which he is best known, Itagaki helped found the Jiyuto

Liberal Party of Japan (1881)

The is the name of several liberal political parties in the history of Japan, two of which existed in the Empire of Japan prior to 1945.-Liberal Party of 1881:...

(Liberal Party), which favored French political doctrines.

In 1882 Okuma Shigenobu

Okuma Shigenobu

Marquis ; was a statesman in the Empire of Japan and the 8th and 17th Prime Minister of Japan...

established the Rikken Kaishintō

Rikken Kaishinto

The was a political party in Empire of Japan. It was also known as simply the ‘Kaishintō’.The Kaishintō was founded by Ōkuma Shigenobu on 16 April 1882, with the assistance of Yano Ryūsuke, Inukai Tsuyoshi and Ozaki Yukio. It received financial backing by the Mitsubishi zaibatsu, and had strong...

(Constitutional Progressive Party), which called for a British-style constitutional democracy. In response, government bureaucrats, local government officials, and other conservatives established the Rikken Teiseitō

Rikken Teiseito

The was a short-lived conservative political party in the Meiji period Empire of Japan. It was also known as simply the ‘Teiseitō’.The Teiseitō was founded in March 1882, by the editor of the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun, Fukuichi Gen'ichirō, and a number of bureaucrats and conservative journalists...

(Imperial Rule Party), a pro-government party, in 1882. Numerous political demonstrations followed, some of them violent, resulting in further government restrictions. The restrictions hindered the political parties and led to divisions within and among them. The Jiyuto, which had opposed the Kaishinto, was disbanded in 1884, and Okuma resigned as Kaishinto president.

Government leaders, long preoccupied with violent threats to stability and the serious leadership split over the Korean affair, generally agreed that constitutional government should someday be established. The Chōshū

Nagato Province

, often called , was a province of Japan. It was at the extreme western end of Honshū, in the area that is today Yamaguchi Prefecture. Nagato bordered on Iwami and Suō Provinces....

leader Kido Takayoshi

Kido Takayoshi

, also referred as Kido Kōin was a Japanese statesman during the Late Tokugawa shogunate and the Meiji Restoration. He used the alias when he worked against the Shogun.-Early life:...

had favored a constitutional form of government since before 1874, and several proposals for constitutional guarantees had been drafted. The oligarchy, however, while acknowledging the realities of political pressure, was determined to keep control. Thus, modest steps were taken.

The Osaka Conference in 1875 resulted in the reorganization of government with an independent judiciary and an appointed Chamber of Elders (Genrōin) tasked with reviewing proposals for a legislature. The emperor declared that "constitutional government shall be established in gradual stages" as he ordered the Council of Elders to draft a constitution.

Three years later, the Conference of Prefectural Governors established elected prefectural assemblies. Although limited in their authority, these assemblies represented a move in the direction of representative government at the national level, and by 1880 assemblies also had been formed in villages and towns. In 1880 delegates from twenty-four prefectures held a national convention to establish the Kokkai Kisei Domei (League for Establishing a National Assembly).

Although the government was not opposed to parliamentary rule, confronted with the drive for "people's rights", it continued to try to control the political situation. New laws in 1875 prohibited press criticism of the government or discussion of national laws. The Public Assembly Law (1880) severely limited public gatherings by disallowing attendance by civil servants and requiring police permission for all meetings.

Within the ruling circle, however, and despite the conservative approach of the leadership, Okuma continued as a lone advocate of British-style government, a government with political parties and a cabinet organized by the majority party, answerable to the national assembly. He called for elections to be held by 1882 and for a national assembly to be convened by 1883; in doing so, he precipitated a political crisis that ended with an 1881 imperial rescript declaring the establishment of a national assembly in 1890 and dismissing Okuma.

Rejecting the British model, Iwakura

Iwakura Tomomi

was a Japanese statesman in the Meiji period. The former 500 Yen banknote issued by the Bank of Japan carried his portrait.-Early life:Iwakura was born in Kyoto as the second son of a low-ranking courtier and nobleman . In 1836 he was adopted by another nobleman, , from whom he received his family...

and other conservatives borrowed heavily from the Prussian constitutional system

Constitution of the German Empire

The Constitution of the German Empire was the basic law of the German Empire of 1871-1919, enacted 16 April 1871. German historians often refer to it as Bismarck's imperial constitution....

. One of the Meiji oligarchy, Itō Hirobumi

Ito Hirobumi

Prince was a samurai of Chōshū domain, Japanese statesman, four time Prime Minister of Japan , genrō and Resident-General of Korea. Itō was assassinated by An Jung-geun, a Korean nationalist who was against the annexation of Korea by the Japanese Empire...

(1841–1909), a Chōshū native long involved in government affairs, was charged with drafting Japan's constitution. He led a Constitutional Study Mission abroad in 1882, spending most of his time in Germany. He rejected the United States Constitution

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It is the framework for the organization of the United States government and for the relationship of the federal government with the states, citizens, and all people within the United States.The first three...

as "too liberal" and the British system as too unwieldy and having a parliament with too much control over the monarchy; the French and Spanish models were rejected as tending toward despotism.

Ito was put in charge of the new Bureau for Investigation of Constitutional Systems in 1884, and the Council of State was replaced in 1885 with a cabinet headed by Ito as prime minister. The positions of chancellor, minister of the left, and minister of the right, which had existed since the 7th century as advisory positions to the emperor, were all abolished. In their place, the Privy Council was established in 1888 to evaluate the forthcoming constitution and to advise the emperor.

To further strengthen the authority of the state, the Supreme War Council was established under the leadership of Yamagata Aritomo

Yamagata Aritomo

Field Marshal Prince , also known as Yamagata Kyōsuke, was a field marshal in the Imperial Japanese Army and twice Prime Minister of Japan. He is considered one of the architects of the military and political foundations of early modern Japan. Yamagata Aritomo can be seen as the father of Japanese...

(1838–1922), a Chōshū native who has been credited with the founding of the modern Japanese army and was to become the first constitutional prime minister. The Supreme War Council developed a German-style general staff system with a chief of staff who had direct access to the emperor and who could operate independently of the army

minister and civilian officials.

When finally granted by the emperor as a sign of his sharing his authority and giving rights and liberties to his subjects, the 1889 Constitution of the Empire of Japan

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan is the name of the state of Japan that existed from the Meiji Restoration on 3 January 1868 to the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of...

(the Meiji Constitution

Meiji Constitution

The ', known informally as the ', was the organic law of the Japanese empire, in force from November 29, 1890 until May 2, 1947.-Outline:...

) provided for the Imperial Diet (Teikoku Gikai), composed of a popularly elected House of Representatives with a very limited franchise of male citizens who were over 25 years of age and paid 15 yen in national taxes, about 1 % of the population, and the House of Peers

House of Peers (Japan)

The ' was the upper house of the Imperial Diet as mandated under the Constitution of the Empire of Japan ....

, composed of nobility and imperial appointees; and a cabinet responsible to the emperor and independent of the legislature. The Diet could approve government legislation and initiate laws, make representations to the government, and submit petitions to the emperor. Nevertheless, in spite of these institutional changes, sovereignty still resided in the emperor on the basis of his divine ancestry.

The new constitution specified a form of government that was still authoritarian in character, with the emperor holding the ultimate power and only minimal concessions made to popular rights and parliamentary mechanisms. Party participation was recognized as part of the political process. The Meiji Constitution was to last as the fundamental law until 1947.

In the early years of constitutional government, the strengths and weaknesses of the Meiji Constitution were revealed. A small clique of Satsuma and Chōshū elite continued to rule Japan, becoming institutionalized as an extra-constitutional body of genro

Genro

was an unofficial designation given to certain retired elder Japanese statesmen, considered the "founding fathers" of modern Japan, who served as informal extraconstitutional advisors to the emperor, during the Meiji, Taishō and early Shōwa periods in Japanese history.The institution of genrō...

(elder statesmen). Collectively, the genro made decisions reserved for the emperor, and the genro, not the emperor, controlled the government politically.

Throughout the period, however, political problems were usually solved through compromise, and political parties gradually increased their power over the government and held an ever larger role in the political process as a result. Between 1891 and 1895, Ito served as prime minister with a cabinet composed mostly of genro who wanted to establish a government party to control the House of Representatives. Although not fully realized, the trend toward party politics was well established.

Society

On its return, one of the first acts of the government was to establish new ranks for the nobility. Five hundred people from the old court nobility, former daimyo, and samurai who had provided valuable service to the emperor were organized in five ranks: prince, marquisMarquis

Marquis is a French and Scottish title of nobility. The English equivalent is Marquess, while in German, it is Markgraf.It may also refer to:Persons:...

, count

Count

A count or countess is an aristocratic nobleman in European countries. The word count came into English from the French comte, itself from Latin comes—in its accusative comitem—meaning "companion", and later "companion of the emperor, delegate of the emperor". The adjective form of the word is...

, viscount

Viscount

A viscount or viscountess is a member of the European nobility whose comital title ranks usually, as in the British peerage, above a baron, below an earl or a count .-Etymology:...

, and baron

Baron

Baron is a title of nobility. The word baron comes from Old French baron, itself from Old High German and Latin baro meaning " man, warrior"; it merged with cognate Old English beorn meaning "nobleman"...

.

It was at this time that the Ee ja nai ka

Ee ja nai ka

was a complex of carnivalesque religious celebrations and communal activities which occurred in many parts of Japan from June 1867 to May 1868, at the end of the Edo period and the start of the Meiji restoration. In West Japan, it appeared at first in the form of dancing festivals, often related to...

movement, a spontaneous outbreak of ecstatic behaviour, took place.

In 1885, the intellectual Yukichi Fukuzawa wrote the influential essay Leaving Asia

Datsu-A Ron

Datsu-A Ron was an editorial which was first published in the Japanese newspaper Jiji Shimpo on March 16, 1885. The writer is thought to be Japanese author and educator Fukuzawa Yukichi, but the original editorial was written anonymously. The editorial was contained in the second volume of...

, arguing that Japan should orient itself at the "civilized countries of the West", leaving behind the "hopelessly backward" Asian neighbors, namely Korea

Korea

Korea ) is an East Asian geographic region that is currently divided into two separate sovereign states — North Korea and South Korea. Located on the Korean Peninsula, Korea is bordered by the People's Republic of China to the northwest, Russia to the northeast, and is separated from Japan to the...

and China. This essay certainly contributed to the economic and technological rise of Japan in the Meiji period but it may also have laid the foundations for later Japanese colonialism

Colonialism

Colonialism is the establishment, maintenance, acquisition and expansion of colonies in one territory by people from another territory. It is a process whereby the metropole claims sovereignty over the colony and the social structure, government, and economics of the colony are changed by...

in the region.

Economy

The Industrial RevolutionIndustrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and technology had a profound effect on the social, economic and cultural conditions of the times...

in Japan occurred during the Meiji period.

There were at least two reasons for the speed of Japan's modernization: the employment of over 3,000 foreign experts (called o-yatoi gaikokujin

O-yatoi gaikokujin

The Foreign government advisors in Meiji Japan, known in Japanese as oyatoi gaikokujin , were those foreign advisors hired by the Japanese government for their specialized knowledge to assist in the modernization of Japan at the end of the Bakufu and during the Meiji era. The term is sometimes...

or 'hired foreigners') in a variety of specialist fields such as teaching English, science, engineering, the army and navy etc.; and the dispatch of many Japanese students overseas to Europe and America, based on the fifth and last article of the Charter Oath of 1868: 'Knowledge shall be sought throughout the world so as to strengthen the foundations of Imperial rule.' This process of modernization was closely monitored and heavily subsidized by the Meiji government, enhancing the power of the great zaibatsu

Zaibatsu

is a Japanese term referring to industrial and financial business conglomerates in the Empire of Japan, whose influence and size allowed for control over significant parts of the Japanese economy from the Meiji period until the end of World War II.-Terminology:...

firms such as Mitsui

Mitsui

is one of the largest corporate conglomerates in Japan and one of the largest publicly traded companies in the world.-History:Founded by Mitsui Takatoshi , who was the fourth son of a shopkeeper in Matsusaka, in what is now today's Mie prefecture...

and Mitsubishi

Mitsubishi

The Mitsubishi Group , Mitsubishi Group of Companies, or Mitsubishi Companies is a Japanese multinational conglomerate company that consists of a range of autonomous businesses which share the Mitsubishi brand, trademark and legacy...

.

Hand in hand, the zaibatsu and government guided the nation, borrowing technology from the West. Japan gradually took control of much of Asia's market for manufactured goods, beginning with textiles. The economic structure became very mercantilistic, importing raw materials and exporting finished products — a reflection of Japan's relative poverty in raw materials.

Japan emerged from the Tokugawa

Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the and the , was a feudal regime of Japan established by Tokugawa Ieyasu and ruled by the shoguns of the Tokugawa family. This period is known as the Edo period and gets its name from the capital city, Edo, which is now called Tokyo, after the name was...

–Tennō

Emperor of Japan

The Emperor of Japan is, according to the 1947 Constitution of Japan, "the symbol of the state and of the unity of the people." He is a ceremonial figurehead under a form of constitutional monarchy and is head of the Japanese Imperial Family with functions as head of state. He is also the highest...

(Keiō

Keio

was a after Genji and before Meiji. The period spanned the years from April 1865 to September 1868. The reigning emperors were and .-Change of era:...

-Meiji) transition in 1868 as the first Asian industrialized nation. Domestic commercial activities and limited foreign trade had met the demands for material culture until the Keiō period, but the modernized Meiji period had radically different requirements. From the onset, the Meiji rulers embraced the concept of a market economy and adopted British and North American forms of free enterprise capitalism. The private sector — in a nation with an abundance of aggressive entrepreneurs — welcomed such change.

Economic reforms included a unified modern currency based on the yen, banking, commercial and tax laws, stock exchanges, and a communications network. Establishment of a modern institutional framework conducive to an advanced capitalist economy took time but was completed by the 1890s. By this time, the government had largely relinquished direct control of the modernization process, primarily for budgetary reasons.

Many of the former daimyo, whose pensions had been paid in a lump sum, benefited greatly through investments they made in emerging industries. Those who had been informally involved in foreign trade before the Meiji Restoration also flourished. Old bakufu-serving firms that clung to their traditional ways failed in the new business environment.

The government was initially involved in economic modernization, providing a number of "model factories" to facilitate the transition to the modern period. After the first twenty years of the Meiji period, the industrial economy expanded rapidly until about 1920 with inputs of advanced Western technology and large private investments. Stimulated by wars and through cautious economic planning, Japan emerged from World War I as a major industrial nation.

Military

Overview

Undeterred by opposition, the Meiji leaders continued to modernize the nation through government-sponsored telegraph cable links to all major Japanese cities and the Asian mainland and construction of railroads, shipyards, munitions factories, mines, textile manufacturing facilities, factories, and experimental agriculture stations. Greatly concerned about national security, the leaders made significant efforts at military modernization, which included establishing a small standing army, a large reserve system, and compulsory militia service for all men. Foreign military systems were studied, foreign advisers, especially French ones, were brought in, and Japanese cadets sent abroad to Europe and the United States to attend military and naval schools.Early Meiji period 1868-1877

In 1854, after Admiral Matthew C. Perry forced the signing of the Treaty of Kanagawa, Japan began to realize it must modernize its military to prevent further intimidation from western powers (Gordon, 2000). However, the Tokugawa shogunate did not officially share this point of view as evidenced by the imprisonment of the Governor of Nagasaki, Shanan Takushima for voicing his views of military reform and weapons modernization (GlobalSecurity.org, 2008).It wasn't until the beginning of the Meiji Era in 1868 that the Japanese government began taking modernization seriously. In 1868, the Japanese government established the Tokyo Arsenal. This arsenal was responsible for the development and manufacture of small arms and associated ammunition (GlobalSecurity.org, 2008). The same year, Masujiro Omura established Japan's first ever military academy in Kyoto. Omura further proposed military billets be filled by all classes of people including farmers and merchants. The shogun class, not happy with Omura's views on conscription, assassinated him the following year (Shinsengumihq.com, n.d.).

In 1870, Japan expanded its military production base by opening another arsenal in Osaka. The Osaka Arsenal was responsible for the production of machine guns and ammunition (National Diet Library, 2008). Also, four gunpowder facilities were also opened at this site. Japan's production capacity gradually improved.

In 1872, Yamagata Aritomo and Saigo Tsugumichi, both new field marshals, founded the Corps of the Imperial Guards. This corps was composed of the warrior classes from the Tosa, Satsuma, and Chusho clans (GlobalSecurity.org, 2008). Also, in the same year, the hyobusho (war office) was replaced with a War Department and a Naval Department. The samurai class suffered great disappointment the following years, when in January the Conscription Law of 1873 was passed. This law required every able bodied male Japanese citizen, regardless of class, to serve a mandatory term of three years with the first reserves and two additional years with the second reserves (GlobalSecurity.org, 2008). This monumental law, signifying the beginning of the end for the samurai class, initially met resistance from both the peasant and warrior alike. The peasant class interpreted the term for military service, ketsu-eki (blood tax) literally, and attempted to avoid service by any means necessary. Avoidance methods included maiming, self-mutilation, and local uprisings (Kublin, 1949, p 32). The samurai were generally resentful of the new, western-style military and at first, refused to stand in formation with the lowly peasant class (GlobalSecurity.org, 2008).

In conjunction with the new conscription law, the Japanese government began modeling their ground forces after the French military. Indeed, the new Japanese army utilized the same rank structure as the French (Kublin, 1949, p 31). The enlisted corps ranks were: private, noncommissioned officers, and officers. The private classes were: joto-hei or upper soldier, itto-sottsu or first-class soldier, and nito-sotsu or second-class soldier. The noncommissioned officer class ranks were: gocho or corporal, gunso or sergeant, socho or sergeant major, and tokumu-socho or special sergeant major. Finally, the officer class is made up of: shoi or second lieutenant, chui or first lieutenant, tai or captain, shosa or major, chusa or lieutenant colonel, taisa or colonel, shosho or major general, chujo or lieutenant general, taisho or general, and gensui or field marshal (GlobalSecurity.org, 2008). The French government also contributed greatly to the training of Japanese officers. Many were employed at the military academy in Kyoto, and many more still were feverishly translating French field manuals for use in the Japanese ranks (GlobalSecuirty.org, 2008).

Despite the Conscription Law of 1873, and all the reforms and progress, the new Japanese army was still untested. That all changed in 1877, when Takamori Saigo, led the last rebellion of the samurai in Kyūshū. In February 1877, Saigo left Kagoshima with a small contingent of soldiers on a journey to Tokyo. Kumamoto castle was the site of the first major engagement as garrisoned forces fired on Saigo's army as they attempted to force their way into the castle. Rather than leave an enemy behind him, Saigo laid siege to the castle. Two days later, Saigo's rebels, while attempting to block a mountain pass encountered advanced elements of the national army enroute to reinforce Kumamoto castle. After a short battle, both sides withdrew to reconstitute their forces . A few weeks later the national army engaged Saigo's rebels in a frontal assault at what is now called the Battle of Tabaruzuka . During this eight day battle, Saigo's nearly ten thousand strong army battled hand-to-hand the equally matched national army. Both sides suffered nearly four thousand casualties during this engagement . Due to conscription however, the Japanese army was able to reconstitute its forces while Saigo's was not. Later, forces loyal to the Emperor broke through rebel lines and managed to end the siege on Kumamoto castle

Kumamoto Castle

is a hilltop Japanese castle located in Kumamoto in Kumamoto Prefecture. It was a large and extremely well fortified castle. The is a concrete reconstruction built in 1960, but several ancillary wooden buildings remain of the original castle. Kumamoto Castle is considered one of the three premier...

after fifty-four days . Saigo's troops fled north, pursued by the national army. The national army caught up with Saigo at Mt. Enodake. Saigo's army was outnumbered seven to one prompting a mass surrender of many samurai .The remaining five hundred samurai loyal to Saigo escaped, travelling south to Kagoshima. The rebellion ended on September 24, 1877 following the final engagement with Imperial forces which resulted in deaths of the remaining forty samurai and Takamori Saigo himself, who, having suffered a fatal bullet wound in the abdomen, was honourably beheaded by his retainer .The army's victory validated the current course of the modernization of the Japanese army as well as ended the era of the samurai.

Foreign relations

When United States Navy ended Japan's sakoku policySakoku

was the foreign relations policy of Japan under which no foreigner could enter nor could any Japanese leave the country on penalty of death. The policy was enacted by the Tokugawa shogunate under Tokugawa Iemitsu through a number of edicts and policies from 1633–39 and remained in effect until...

, and thus its isolation, the latter found itself defenseless against military pressures and economic exploitation by the Western powers. For Japan to emerge from the feudal period, it had to avoid the colonial fate of other Asian countries by establishing genuine national independence and equality. Japan released the Chinese coolies from a western ship

María Luz Incident

The was a diplomatic incident between the early Meiji government of the Empire of Japan and the Republic of Peru over a merchant ship with Chinese indentured labourers in Yokohama in 1872...

in 1872, after which the Qing Imperial Government China

Qing Dynasty

The Qing Dynasty was the last dynasty of China, ruling from 1644 to 1912 with a brief, abortive restoration in 1917. It was preceded by the Ming Dynasty and followed by the Republic of China....

gave thanks to Japan.

Following her defeat of China in Korea in the Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), Japan broke through as an international power with a victory against Russia in Manchuria

Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical name given to a large geographic region in northeast Asia. Depending on the definition of its extent, Manchuria usually falls entirely within the People's Republic of China, or is sometimes divided between China and Russia. The region is commonly referred to as Northeast...

(north-eastern China) in the Russo-Japanese War

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War was "the first great war of the 20th century." It grew out of rival imperial ambitions of the Russian Empire and Japanese Empire over Manchuria and Korea...

of 1904–1905. Allied with Britain since the Anglo-Japanese Alliance

Anglo-Japanese Alliance

The first was signed in London at what is now the Lansdowne Club, on January 30, 1902, by Lord Lansdowne and Hayashi Tadasu . A diplomatic milestone for its ending of Britain's splendid isolation, the alliance was renewed and extended in scope twice, in 1905 and 1911, before its demise in 1921...

signed in London on January 30, 1902, Japan joined the Allies in World War I, seizing German-held territory in China and the Pacific in the process, but otherwise remained largely out of the conflict.

After the war, a weakened Europe left a greater share in international markets to the U.S. and Japan, which emerged greatly strengthened. Japanese competition made great inroads into hitherto European-dominated markets in Asia, not only in China, but even in European colonies like India and Indonesia

Indonesia

Indonesia , officially the Republic of Indonesia , is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania. Indonesia is an archipelago comprising approximately 13,000 islands. It has 33 provinces with over 238 million people, and is the world's fourth most populous country. Indonesia is a republic, with an...

, reflecting the development of the Meiji era.

Observers and historians

A key foreign observer of the remarkable and rapid changes in Japanese societyCulture of Japan

The culture of Japan has evolved greatly over the millennia, from the country's prehistoric Jōmon period to its contemporary hybrid culture, which combines influences from Asia, Europe and North America...

in this period was Ernest Mason Satow

Ernest Mason Satow

Sir Ernest Mason Satow PC, GCMG, , known in Japan as "" , known in China as "薩道義" or "萨道义", was a British scholar, diplomat and Japanologist....

, resident in Japan 1862–83 and 1895–1900.

See also

- Japanese nationalismJapanese nationalismencompasses a broad range of ideas and sentiments harbored by the Japanese people over the last two centuries regarding their native country, its cultural nature, political form and historical destiny...

- List of political figures of Meiji Japan

- Rurouni KenshinRurouni Kenshin, also known as Rurouni Kenshin and Samurai X, is a Japanese manga series written and illustrated by Nobuhiro Watsuki. The fictional setting takes place during the early Meiji period in Japan. The story is about a fictional assassin named Himura Kenshin, from the Bakumatsu who becomes a wanderer to...

, a historical mangaMangaManga is the Japanese word for "comics" and consists of comics and print cartoons . In the West, the term "manga" has been appropriated to refer specifically to comics created in Japan, or by Japanese authors, in the Japanese language and conforming to the style developed in Japan in the late 19th...

set in the Meiji period

External links

- Meiji Taisho 1868-1926

- Meiji Period Architecture (1868-1912)

- National Diet LibraryNational Diet LibraryThe is the only national library in Japan. It was established in 1948 for the purpose of assisting members of the in researching matters of public policy. The library is similar in purpose and scope to the U.S...

, "The Japanese Calendar" -- historical overview plus illustrative images from library's collection

| Meiji | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | 11th | 12th | 13th | 14th | 15th | 16th | 17th | 18th | 19th | 20th |

| Gregorian Gregorian calendar The Gregorian calendar, also known as the Western calendar, or Christian calendar, is the internationally accepted civil calendar. It was introduced by Pope Gregory XIII, after whom the calendar was named, by a decree signed on 24 February 1582, a papal bull known by its opening words Inter... |

1868 | 1869 | 1870 | 1871 | 1872 | 1873 | 1874 | 1875 | 1876 | 1877 | 1878 | 1879 | 1880 | 1881 | 1882 | 1883 | 1884 | 1885 | 1886 | 1887 |

| Meiji | 21st | 22nd | 23rd | 24th | 25th | 26th | 27th | 28th | 29th | 30th | 31st | 32nd | 33rd | 34th | 35th | 36th | 37th | 38th | 39th | 40th |

| Gregorian Gregorian calendar The Gregorian calendar, also known as the Western calendar, or Christian calendar, is the internationally accepted civil calendar. It was introduced by Pope Gregory XIII, after whom the calendar was named, by a decree signed on 24 February 1582, a papal bull known by its opening words Inter... |

1888 | 1889 | 1890 | 1891 | 1892 | 1893 | 1894 | 1895 | 1896 | 1897 | 1898 | 1899 | 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 |

| Meiji | 41st | 42nd | 43rd | 44th | 45th |

| Gregorian Gregorian calendar The Gregorian calendar, also known as the Western calendar, or Christian calendar, is the internationally accepted civil calendar. It was introduced by Pope Gregory XIII, after whom the calendar was named, by a decree signed on 24 February 1582, a papal bull known by its opening words Inter... |

1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 |

Preceded by: Keiō Keio was a after Genji and before Meiji. The period spanned the years from April 1865 to September 1868. The reigning emperors were and .-Change of era:... |

Era or nengō Japanese era name The Japanese era calendar scheme is a common calendar scheme used in Japan, which identifies a year by the combination of the and the year number within the era... : Meiji |

Succeeded by: Taishō Taisho period The , or Taishō era, is a period in the history of Japan dating from July 30, 1912 to December 25, 1926, coinciding with the reign of the Taishō Emperor. The health of the new emperor was weak, which prompted the shift in political power from the old oligarchic group of elder statesmen to the Diet... |