Michael Cardew

Encyclopedia

Michael Cardew, OBE, was an English

studio potter

who worked in West Africa for twenty years.

Cardew was the fourth child of Arthur Cardew, a civil servant, and Alexandra Kitchin

, the eldest daughter of G.W.Kitchin

, the first Chancellor of Durham University. His family had a holiday home in North Devon

, where Arthur Cardew collected Devon country pottery. Cardew first saw this pottery being made in the workshop of Edwin Beer Fishley at Braunton

and learned to make pottery on the wheel from Fishley's grandson, William Fishley Holland.

He gained a scholarship to read Classics at Exeter College

, Oxford. Already preoccupied with pottery, he graduated with a third class degree in 1923.

Cardew was the first apprentice at the Leach Pottery

, St.Ives

, Cornwall

, in 1923. He shared an interest in slipware

with Bernard Leach

and was influenced by the pottery of Shoji Hamada

. In 1926 he left St Ives to re-start the Greet Potteries at Winchcombe

in Gloucestershire. With the help of former chief thrower Elijah Comfort and fourteen year-old Sydney Tustin, he set about rebuilding the derelict pottery. Cardew aimed to make pottery in the seventeenth century English slipware

tradition, functional and affordable by people with moderate incomes. After some experimentation, pottery was made with local clay and fired in a traditional bottle kiln. Charlie Tustin joined the team in 1935 followed in 1936 by Ray Finch, who bought the pottery from Cardew and still works there. The pottery is now known as Winchcombe Pottery

.

Cardew married the painter Mariel Russell in 1933. They had three sons, Seth

(b.1934), Cornelius

(1936-1981) and Ennis (b.1938).

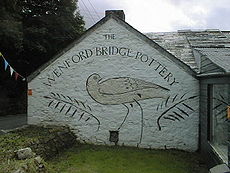

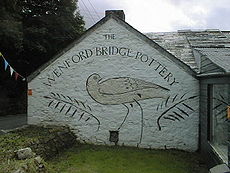

In 1939, an inheritance enabled Cardew to fulfill his dream of living and working in Cornwall. He bought an inn at Wenford Bridge, St Breward

, and converted it to a pottery, where he produced earthenware

and stoneware

. He built the first kiln

at Wenford Bridge with the help of Michael Leach, Bernard Leach's son. It was fired only a few times before the outbreak of war, when blackout restrictions brought work to an end. In 1950 an Australian potter, Ivan McMeekin, became a partner and ran the pottery while Cardew was in Africa. McMeekin built a downdraught kiln and produced stoneware

there until 1954.

Wenford Bridge did not make enough money to support Cardew and his family, and in 1942 he accepted a salaried post in the Colonial Service

Wenford Bridge did not make enough money to support Cardew and his family, and in 1942 he accepted a salaried post in the Colonial Service

as a ceramist at Achimota School

, an élite school for Africans in the Gold Coast (Ghana

). Although Cardew's main motivation for taking the post was financial, he had become convinced (partly though his reading of Marx

) that there should be a closer relationship between the studio potter and industry. Following the outbreak of war, the school's supervisor of arts and crafts, H.V.Meyerowitz, recommended that the pottery department should expand into a handcraft-based industry that might provide all the pottery needs of British West Africa. African colonies had hitherto depended on the export of commodities, but enemy shipping made this almost impossible. The Colonial Office adopted instead a policy developing indigenous industries and eventually accepted Meyerowitz's idea. They agreed to fund the Achimota pottery, which they intended should become profitable, and hired Cardew to build and manage it in nearby Alajo. This gave him the opportunity to apply his ideas on an industrial scale, and he went to the task with enthusiasm. The pottery employed about sixty people and had large orders from the rubber industry and the army. However, it did not meet its production targets and was unprofitable. There was an apprentice rebellion and a huge kiln failure. Cardew admits that his enthusiasm developed into fanaticism. In 1945 Meyerowitz committed suicide. All these disasters led to the closure of Alajo.

In 1945 Cardew moved to Vumë on the River Volta where he set up a pottery with his own resources. He chose to remain in Africa partly to erase the failure of Alajo and partly to vindicate the ideas of Meyerowitz, to whom he felt he owed a debt. He records in his autobiography his obsession to prove to the colonial administrators "that they were wrong to close down Alajo, and that a small pottery in a village would be successful in every way, provided it was allowed to develop naturally." He struggled with difficult clay and kiln failures for three years and later judged the Vumë pottery to have been unsuccessful, but its products are among his most highly regarded pots.

He returned to England in 1948 and made stoneware pottery at Wenford Bridge.

In 1951 he was appointed by the Nigeria

n government to the post of Pottery Officer in the Department of Commerce and Industry, during which time he built and developed a successful pottery training centre at Abuja

in Northern Nigeria. His trainees were mainly Hausa

and Gwari

men, but he spotted the pots of Ladi Kwali

and in 1954 she became the first woman potter at the Training Centre, soon followed by other women. As a result of Cardew's extensive contact with and admiration of African pottery, his later work shows its influence. He returned to Wenford Bridge on his retirement in 1965.

Through his contact with Ivan McMeekin, in 1968 he was invited by the University of New South Wales

to spend six months in the Northern Territory

of Australia

introducing pottery to the aborigines

. He traveled in America, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, making pots, demonstrating, writing and teaching.

He wrote Pioneer Pottery, an account of pottery-making based on his experiences in Africa, which assumes that the potter will have to find and prepare his own materials and make all his tools and equipment, and an autobiography, A Pioneer Potter.

Bernard Leach said that Cardew was his best pupil. He has been described as "one of the finest potters of the century and one of the greatest slipware potters of all times." The decorative style of his slipware is usually trailed or scratched and is free and original. The stoneware he made at Vumë and Abuja is similarly well regarded. There are collections of his work in museums in Britain, the United States, Australia and New Zealand.

He was appointed MBE

in 1964 and OBE in 1981. He was due to be knighted at the time of his death.

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

studio potter

Studio pottery

Studio pottery is made by modern artists working alone or in small groups, producing unique items of pottery in small quantities, typically with all stages of manufacture carried out by one individual. Much studio pottery is tableware or cookware but an increasing number of studio potters produce...

who worked in West Africa for twenty years.

Cardew was the fourth child of Arthur Cardew, a civil servant, and Alexandra Kitchin

Alexandra Kitchin

Alexandra 'Xie' Rhoda Kitchin was a notable 'child-friend' and favourite photographic subject of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson ....

, the eldest daughter of G.W.Kitchin

George William Kitchin

George William Kitchin was the first Chancellor of the University of Durham, from the institution of the role in 1908 till his death in 1912. He was also the last Dean of Durham Cathedral to govern the university....

, the first Chancellor of Durham University. His family had a holiday home in North Devon

North Devon

North Devon is the northern part of the English county of Devon. It is also the name of a local government district in Devon. Its council is based in Barnstaple. Other towns and villages in the North Devon District include Braunton, Fremington, Ilfracombe, Instow, South Molton, Lynton and Lynmouth...

, where Arthur Cardew collected Devon country pottery. Cardew first saw this pottery being made in the workshop of Edwin Beer Fishley at Braunton

Braunton

Braunton is situated west of Barnstaple, Devon, England and is claimed to be the largest village in England, with a population in 2001 of 7,510. It is home to the nearby Braunton Great Field and Braunton Burrows, a National Nature and UNESCO Biosphere Reserve....

and learned to make pottery on the wheel from Fishley's grandson, William Fishley Holland.

He gained a scholarship to read Classics at Exeter College

Exeter College, Oxford

Exeter College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England and the fourth oldest college of the University. The main entrance is on the east side of Turl Street...

, Oxford. Already preoccupied with pottery, he graduated with a third class degree in 1923.

Cardew was the first apprentice at the Leach Pottery

Leach Pottery

The Leach Pottery was founded in 1920 by Bernard Leach and Shoji Hamada in St Ives, Cornwall, in the United Kingdom.The buildings have grown from an old cow / tin-ore shed in the 19th century to a pottery in the 1920s when Hamada and Leach first attempted to construct a climbing kiln, this was the...

, St.Ives

St Ives, Cornwall

St Ives is a seaside town, civil parish and port in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The town lies north of Penzance and west of Camborne on the coast of the Celtic Sea. In former times it was commercially dependent on fishing. The decline in fishing, however, caused a shift in commercial...

, Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

, in 1923. He shared an interest in slipware

Slipware

Slipware is a type of pottery identified by its primary decorating process where slip was placed onto the leather-hard clay body surface by dipping, painting or splashing...

with Bernard Leach

Bernard Leach

Bernard Howell Leach, CBE, CH , was a British studio potter and art teacher. He is regarded as the "Father of British studio pottery"-Biography:...

and was influenced by the pottery of Shoji Hamada

Shoji Hamada

was a Japanese potter. He was a significant influence on studio pottery of the twentieth century, and a major figure of the mingei folk-art movement, establishing the town of Mashiko as a world-renowned pottery centre.- Biography :...

. In 1926 he left St Ives to re-start the Greet Potteries at Winchcombe

Winchcombe

Winchcombe is a Cotswold town in the local authority district of Tewkesbury, in Gloucestershire, England. Its population according to the 2001 census was 4,379.-Early history:...

in Gloucestershire. With the help of former chief thrower Elijah Comfort and fourteen year-old Sydney Tustin, he set about rebuilding the derelict pottery. Cardew aimed to make pottery in the seventeenth century English slipware

Slipware

Slipware is a type of pottery identified by its primary decorating process where slip was placed onto the leather-hard clay body surface by dipping, painting or splashing...

tradition, functional and affordable by people with moderate incomes. After some experimentation, pottery was made with local clay and fired in a traditional bottle kiln. Charlie Tustin joined the team in 1935 followed in 1936 by Ray Finch, who bought the pottery from Cardew and still works there. The pottery is now known as Winchcombe Pottery

Winchcombe Pottery

Winchcombe Pottery, near Winchcombe in Northern Gloucestershire, is an English craft pottery founded in 1926.- Early history :From 1800 there has been a pottery on the current site in Greet just one mile North of Winchcombe, which continued until 1914 when the outbreak of the Great War caused its...

.

Cardew married the painter Mariel Russell in 1933. They had three sons, Seth

Seth Cardew

Seth Cardew is an English studio potter. He is the son of the influential potter Michael Cardew and the brother of the composer Cornelius Cardew....

(b.1934), Cornelius

Cornelius Cardew

Cornelius Cardew was an English experimental music composer, and founder of the Scratch Orchestra, an experimental performing ensemble. He later rejected the avant-garde in favour of a politically motivated "people's liberation music".-Biography:Cardew was born in Winchcombe, Gloucestershire...

(1936-1981) and Ennis (b.1938).

In 1939, an inheritance enabled Cardew to fulfill his dream of living and working in Cornwall. He bought an inn at Wenford Bridge, St Breward

St Breward

St Breward is a civil parish and village in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated on the western side of Bodmin Moor approximately 6 miles north of Bodmin.The parish name derives from Saint Branwalader...

, and converted it to a pottery, where he produced earthenware

Earthenware

Earthenware is a common ceramic material, which is used extensively for pottery tableware and decorative objects.-Types of earthenware:Although body formulations vary between countries and even between individual makers, a generic composition is 25% ball clay, 28% kaolin, 32% quartz, and 15%...

and stoneware

Stoneware

Stoneware is a vitreous or semi-vitreous ceramic ware with a fine texture. Stoneware is made from clay that is then fired in a kiln, whether by an artisan to make homeware, or in an industrial kiln for mass-produced or specialty products...

. He built the first kiln

Kiln

A kiln is a thermally insulated chamber, or oven, in which a controlled temperature regime is produced. Uses include the hardening, burning or drying of materials...

at Wenford Bridge with the help of Michael Leach, Bernard Leach's son. It was fired only a few times before the outbreak of war, when blackout restrictions brought work to an end. In 1950 an Australian potter, Ivan McMeekin, became a partner and ran the pottery while Cardew was in Africa. McMeekin built a downdraught kiln and produced stoneware

Stoneware

Stoneware is a vitreous or semi-vitreous ceramic ware with a fine texture. Stoneware is made from clay that is then fired in a kiln, whether by an artisan to make homeware, or in an industrial kiln for mass-produced or specialty products...

there until 1954.

Colonial Office

Colonial Office is the government agency which serves to oversee and supervise their colony* Colonial Office - The British Government department* Office of Insular Affairs - the American government agency* Reichskolonialamt - the German Colonial Office...

as a ceramist at Achimota School

Achimota School

Achimota School , is an elite and highly selective co-educational secondary school located at Achimota in Accra, Ghana. It was established and commenced operations in 1924 and formally opened in 1927 by Sir Frederick Gordon Guggisberg -- then governor of the Gold Coast...

, an élite school for Africans in the Gold Coast (Ghana

Ghana

Ghana , officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country located in West Africa. It is bordered by Côte d'Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, Togo to the east, and the Gulf of Guinea to the south...

). Although Cardew's main motivation for taking the post was financial, he had become convinced (partly though his reading of Marx

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of social science and the socialist political movement...

) that there should be a closer relationship between the studio potter and industry. Following the outbreak of war, the school's supervisor of arts and crafts, H.V.Meyerowitz, recommended that the pottery department should expand into a handcraft-based industry that might provide all the pottery needs of British West Africa. African colonies had hitherto depended on the export of commodities, but enemy shipping made this almost impossible. The Colonial Office adopted instead a policy developing indigenous industries and eventually accepted Meyerowitz's idea. They agreed to fund the Achimota pottery, which they intended should become profitable, and hired Cardew to build and manage it in nearby Alajo. This gave him the opportunity to apply his ideas on an industrial scale, and he went to the task with enthusiasm. The pottery employed about sixty people and had large orders from the rubber industry and the army. However, it did not meet its production targets and was unprofitable. There was an apprentice rebellion and a huge kiln failure. Cardew admits that his enthusiasm developed into fanaticism. In 1945 Meyerowitz committed suicide. All these disasters led to the closure of Alajo.

In 1945 Cardew moved to Vumë on the River Volta where he set up a pottery with his own resources. He chose to remain in Africa partly to erase the failure of Alajo and partly to vindicate the ideas of Meyerowitz, to whom he felt he owed a debt. He records in his autobiography his obsession to prove to the colonial administrators "that they were wrong to close down Alajo, and that a small pottery in a village would be successful in every way, provided it was allowed to develop naturally." He struggled with difficult clay and kiln failures for three years and later judged the Vumë pottery to have been unsuccessful, but its products are among his most highly regarded pots.

He returned to England in 1948 and made stoneware pottery at Wenford Bridge.

In 1951 he was appointed by the Nigeria

Nigeria

Nigeria , officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a federal constitutional republic comprising 36 states and its Federal Capital Territory, Abuja. The country is located in West Africa and shares land borders with the Republic of Benin in the west, Chad and Cameroon in the east, and Niger in...

n government to the post of Pottery Officer in the Department of Commerce and Industry, during which time he built and developed a successful pottery training centre at Abuja

Abuja

Abuja is the capital city of Nigeria. It is located in the centre of Nigeria, within the Federal Capital Territory . Abuja is a planned city, and was built mainly in the 1980s. It officially became Nigeria's capital on 12 December 1991, replacing Lagos...

in Northern Nigeria. His trainees were mainly Hausa

Hausa people

The Hausa are one of the largest ethnic groups in West Africa. They are a Sahelian people chiefly located in northern Nigeria and southeastern Niger, but having significant numbers living in regions of Cameroon, Ghana, Cote d'Ivoire, Chad and Sudan...

and Gwari

Gwari

Gbagyi are an ethnic group in central Nigeria. They are predominantly found in the Niger and Kaduna States and the Federal Capital Territory...

men, but he spotted the pots of Ladi Kwali

Ladi Kwali

Ladi Kwali was a Nigerian potter.She was born in the village of Kwali in the Gwari region of Northern Nigeria, where pottery was a common occupation among women. She learned to make pottery as a child using the traditional method of coiling. She made large pots for use as water jars and cooking...

and in 1954 she became the first woman potter at the Training Centre, soon followed by other women. As a result of Cardew's extensive contact with and admiration of African pottery, his later work shows its influence. He returned to Wenford Bridge on his retirement in 1965.

Through his contact with Ivan McMeekin, in 1968 he was invited by the University of New South Wales

University of New South Wales

The University of New South Wales , is a research-focused university based in Kensington, a suburb in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia...

to spend six months in the Northern Territory

Northern Territory

The Northern Territory is a federal territory of Australia, occupying much of the centre of the mainland continent, as well as the central northern regions...

of Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

introducing pottery to the aborigines

Australian Aborigines

Australian Aborigines , also called Aboriginal Australians, from the latin ab originem , are people who are indigenous to most of the Australian continentthat is, to mainland Australia and the island of Tasmania...

. He traveled in America, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, making pots, demonstrating, writing and teaching.

He wrote Pioneer Pottery, an account of pottery-making based on his experiences in Africa, which assumes that the potter will have to find and prepare his own materials and make all his tools and equipment, and an autobiography, A Pioneer Potter.

Bernard Leach said that Cardew was his best pupil. He has been described as "one of the finest potters of the century and one of the greatest slipware potters of all times." The decorative style of his slipware is usually trailed or scratched and is free and original. The stoneware he made at Vumë and Abuja is similarly well regarded. There are collections of his work in museums in Britain, the United States, Australia and New Zealand.

He was appointed MBE

MBE

MBE can stand for:* Mail Boxes Etc.* Management by exception* Master of Bioethics* Master of Bioscience Enterprise* Master of Business Engineering* Master of Business Economics* Mean Biased Error...

in 1964 and OBE in 1981. He was due to be knighted at the time of his death.