Military history of Zimbabwe

Encyclopedia

Military history

Military history is a humanities discipline within the scope of general historical recording of armed conflict in the history of humanity, and its impact on the societies, their cultures, economies and changing intra and international relationships....

of Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe is a landlocked country located in the southern part of the African continent, between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers. It is bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the southwest, Zambia and a tip of Namibia to the northwest and Mozambique to the east. Zimbabwe has three...

chronicles a vast time period and complex events from the dawn of history until the present time. It covers invasions of native peoples of Africa (Shona

Shona people

Shona is the name collectively given to two groups of people in the east and southwest of Zimbabwe, north eastern Botswana and southern Mozambique.-Shona Regional Classification:...

and Ndebele), colonization by Europeans (Portuguese

Portuguese people

The Portuguese are a nation and ethnic group native to the country of Portugal, in the west of the Iberian peninsula of south-west Europe. Their language is Portuguese, and Roman Catholicism is the predominant religion....

, Boer

Boer

Boer is the Dutch and Afrikaans word for farmer, which came to denote the descendants of the Dutch-speaking settlers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 18th century, as well as those who left the Cape Colony during the 19th century to settle in the Orange Free State,...

and British people

British people

The British are citizens of the United Kingdom, of the Isle of Man, any of the Channel Islands, or of any of the British overseas territories, and their descendants...

), and civil wars.

San and invasion by ironworking cultures

Stone Age evidence indicates that the San people, now living mostly in the Kalahari DesertKalahari Desert

The Kalahari Desert is a large semi-arid sandy savannah in Southern Africa extending , covering much of Botswana and parts of Namibia and South Africa, as semi-desert, with huge tracts of excellent grazing after good rains. The Kalahari supports more animals and plants than a true desert...

, are the descendants of this region’s original inhabitants, almost 100 000 years ago. There are also remnants of several ironworking cultures dating back to AD 300. Little is known of the early ironworkers, but it is believed that they put pressure on the San and gradually took over the land.

Shona invasion

Shona people

Shona is the name collectively given to two groups of people in the east and southwest of Zimbabwe, north eastern Botswana and southern Mozambique.-Shona Regional Classification:...

(Gokomere

Gokomere

Gokomere is a place in Zimbabwe, sixteen km from Masvingo known for its rock art dating from 300 to 650 AD.The ancient Bantu people who inhabited the area of Great Zimbabwe around the 4th century AD probably built the complex between 1000 and 1200 AD...

, Sotho-Tswana

Sotho-Tswana

The Sotho–Tswana is the most commonly accepted name for a group of communities which speak Bantu languages living primarily in South Africa, Lesotho, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Zambia.-Language:...

and related tribes) arrived from the north and the both the San and the early ironworkers were driven out. This group gave rise to the maShona and the waRozwi tribes, and probably also gave rise to the Lemba

Lemba

The Lemba or 'wa-Remba' are a southern African ethnic group to be found in Zimbabwe and South Africa with some little known branches in Mozambique and Malawi. According to Parfitt they are thought to number 70,000...

people through a merger with descent from the ancient Jews

Jews

The Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

who arrived in this region via Sena in Yemen. By the 15th century, the Shona had established a strong empire, known as the Munhumutapa Empire

Munhumutapa Empire

The Kingdom of Mutapa, sometimes referred to as the Mutapa Empire was a Shona kingdom which stretched between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers of southern Africa in the modern states of Zimbabwe and Mozambique...

(also called Monomotapa or Mwene Mutapa Empire), with its capital at the ancient city of Zimbabwe -- Great Zimbabwe

Great Zimbabwe

Great Zimbabwe is a ruined city that was once the capital of the Kingdom of Zimbabwe, which existed from 1100 to 1450 C.E. during the country’s Late Iron Age. The monument, which first began to be constructed in the 11th century and which continued to be built until the 14th century, spanned an...

. This empire ruled territory now falling within the modern states of Zimbabwe (which took its name from this city) and Mozambique

Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique , is a country in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west and Swaziland and South Africa to the southwest...

, but the empire was split by the end of the 15th century with southern part becoming the Urozwi Empire.

The Portuguese

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

began their attempts to subdue the Shona states as early as 1505 but were confined to the coast until 1513. The states were also torn apart by rival factions and trade in gold was gradually replaced by a trade in slaves

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

. The empire finally collapsed in 1629 and never recovered. Remnants of the government established another Mutapa kingdom in Mozambique

Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique , is a country in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west and Swaziland and South Africa to the southwest...

sometimes called Karanga

Karanga

Karanga may refer to:* Karanga , Mangaia, Cook Islands* Karanga , an element of Māori cultural protocol, the calling of visitors onto a marae.* Ikalanga language* "Te Karanga", a song by Rhian Sheehan* a clan of the Shona people...

, who reigned in the region until 1902.

Mfecane

Mfecane (ZuluZulu language

Zulu is the language of the Zulu people with about 10 million speakers, the vast majority of whom live in South Africa. Zulu is the most widely spoken home language in South Africa as well as being understood by over 50% of the population...

), also known as the Difaqane or Lifaqane (Sesotho

Sesotho language

The Sotho language, also known as Sesotho, Southern Sotho, or Southern Sesotho, is a Bantu language spoken primarily in South Africa, where it is one of the 11 official languages, and in Lesotho, where it is the national language...

), is an African expression which means something like "the crushing" or "scattering". It describes a period of widespread chaos and disturbance in southern Africa

Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost region of the African continent, variably defined by geography or geopolitics. Within the region are numerous territories, including the Republic of South Africa ; nowadays, the simpler term South Africa is generally reserved for the country in English.-UN...

during the period between 1815 and about 1835 which resulted from the rise to power of Shaka

Shaka

Shaka kaSenzangakhona , also known as Shaka Zulu , was the most influential leader of the Zulu Kingdom....

, the Zulu

Zulu Kingdom

The Zulu Kingdom, sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire or, rather imprecisely, Zululand, was a monarchy in Southern Africa that extended along the coast of the Indian Ocean from the Tugela River in the south to Pongola River in the north....

king and military leader who conquered the Nguni people

Nguni people

-History:The ancient history of the Nguni people is wrapped up in their oral history. According to legend they were a people who migrated from Egypt to the Great Lakes region of sub-equatorial Central/East Africa...

s between the Tugela and Pongola rivers in the beginning of the nineteenth century, and created a militaristic

Militarism

Militarism is defined as: the belief or desire of a government or people that a country should maintain a strong military capability and be prepared to use it aggressively to defend or promote national interests....

kingdom in the region. The Mfecane also led to the formation and consolidation of other groups — such as the Ndebele Kingdom, the Mfengu

Mfengu

The Fengu are a Bantu people; originally closely related to the Zulu people. They were previously known in English as the "Fingo" people, and they gave their name to the district of Fingoland , the South West portion of the Transkei division, in the Cape Province...

and the Makololo

Makololo

The Makololo are a people of Southern Africa, closely related to the Basotho, from which they separated themselves in the early 19th century. Originally residing in what is now South Africa, they were displaced by the Zulu expansion under Shaka and migrated north through Botswana to Barotseland in...

— and the creation of states such as the modern Lesotho

Lesotho

Lesotho , officially the Kingdom of Lesotho, is a landlocked country and enclave, surrounded by the Republic of South Africa. It is just over in size with a population of approximately 2,067,000. Its capital and largest city is Maseru. Lesotho is a member of the Commonwealth of Nations. The name...

.

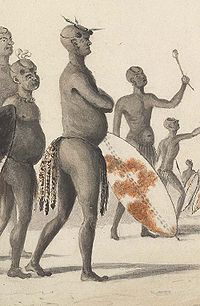

Mzilikazi

Mzilikazi , also sometimes called Mosilikatze, was a Southern African king who founded the Matabele kingdom , Matabeleland, in what became Rhodesia and is now Zimbabwe. He was born the son of Matshobana near Mkuze, Zululand and died at Ingama, Matabeleland...

, originally a lieutenant of Zulu

Zulu Kingdom

The Zulu Kingdom, sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire or, rather imprecisely, Zululand, was a monarchy in Southern Africa that extended along the coast of the Indian Ocean from the Tugela River in the south to Pongola River in the north....

King Shaka

Shaka

Shaka kaSenzangakhona , also known as Shaka Zulu , was the most influential leader of the Zulu Kingdom....

who was pushed from his own territories to the west by the Zulu armies. After a brief alliance with the Transvaal Ndebele, Mzilikazi became leader of the Ndebele people. Many of the Shona people were incorporated and the rest were either made satellite territories who paid taxes to the Ndebele Kingdom. He called his new nation Mthwakazi

Mthwakazi

Mthwakazi This word Mthwakazi is derived from the name of Queen Mu-Thwa, the first ruler of the Mthwakazi territory who ruled around 7,000 years ago...

(which the British later called Matabeleland

Matabeleland

Modern day Matabeleland is a region in Zimbabwe divided into three provinces: Matabeleland North, Bulawayo and Matabeleland South. These provinces are in the west and south-west of Zimbabwe, between the Limpopo and Zambezi rivers. The region is named after its inhabitants, the Ndebele people...

), a name derived from the original settlers the San people called aba Thwa (The Ndebele called themselves Matabele, but because of linguistic differences, were called Ndebele by the local Sotho-Tswana.) Mzilikazi's invasion of the Transvaal

South African Republic

The South African Republic , often informally known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer-ruled country in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century. Not to be confused with the present-day Republic of South Africa, it occupied the area later known as the South African...

was one part of a vast series of inter-related wars, forced migrations and famines that indigenous people and later historians came to call the Mfecane. In the Transvaal, the Mfecane severely weakened and disrupted the towns and villages of the Sotho-Tswana chiefdoms, their political systems and economies, making them very weak, and easy to colonize

Colonialism

Colonialism is the establishment, maintenance, acquisition and expansion of colonies in one territory by people from another territory. It is a process whereby the metropole claims sovereignty over the colony and the social structure, government, and economics of the colony are changed by...

by the European settlers who would shortly arrive from the south.

As Ndebele moved into Transvaal, the remnants of the Bavenda retreated north to the Waterberg and Zoutpansberg, while Mzilikazi made his chief kraal north of the Magaliesberg mountains near present day Pretoria

Pretoria

Pretoria is a city located in the northern part of Gauteng Province, South Africa. It is one of the country's three capital cities, serving as the executive and de facto national capital; the others are Cape Town, the legislative capital, and Bloemfontein, the judicial capital.Pretoria is...

, with an important military outpost to guard trade routes to the north at Mosega, not far from the site of the modern town of Zeerust. From about 1827 until about 1836, Mzilikazi dominated the southwestern Transvaal. Before that time the region between the Vaal and Limpopo was scarcely known to Europeans, but in 1829, Mzilikazi was visited at Mosega by Robert Moffat

Robert Moffat

Robert Moffat was a Scottish Congregationalist missionary to Africa, and father in law of David Livingstone....

, and between that date and 1836 a few British traders and explorers visited the country and made known its principal features.

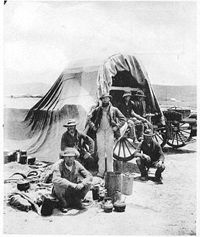

Boer confrontations

In the 1830s and the 1840s, descendants of DutchDutch people

The Dutch people are an ethnic group native to the Netherlands. They share a common culture and speak the Dutch language. Dutch people and their descendants are found in migrant communities worldwide, notably in Suriname, Chile, Brazil, Canada, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand, and the United...

and other settlers, collectively known as Boer

Boer

Boer is the Dutch and Afrikaans word for farmer, which came to denote the descendants of the Dutch-speaking settlers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 18th century, as well as those who left the Cape Colony during the 19th century to settle in the Orange Free State,...

s (farmers) or Voortrekkers

Voortrekkers

The Voortrekkers were emigrants during the 1830s and 1840s who left the Cape Colony moving into the interior of what is now South Africa...

(pioneers), left the British Cape Colony

Cape Colony

The Cape Colony, part of modern South Africa, was established by the Dutch East India Company in 1652, with the founding of Cape Town. It was subsequently occupied by the British in 1795 when the Netherlands were occupied by revolutionary France, so that the French revolutionaries could not take...

, in what was to be called the Great Trek

Great Trek

The Great Trek was an eastward and north-eastward migration away from British control in the Cape Colony during the 1830s and 1840s by Boers . The migrants were descended from settlers from western mainland Europe, most notably from the Netherlands, northwest Germany and French Huguenots...

. With their military technology, they overcame the local forces with relative ease, and formed several small Boer republics in areas beyond British control, without a central government.

Andries Hendrik Potgieter

Andries Hendrik Potgieter, known as Hendrik Potgieter was a Voortrekker leader. He served as the first head of state of Potchefstroom from 1840 and 1845 and also as the first head of state of Zoutpansberg from 1845 to 1852.Potgieter was born in the Tarkastad district of the Cape Colony, the second...

, was attacked by an Ndebele force of about 5,000, who looted all of Potgiester's livestock, but were unable to defeat the laager. One of the Sotho-Tswana chiefs, Chief Moroko of the Rolong people, who had earlier fled the Difaqane to the south to create the settlement of Thaba-Nchu, sent fresh livestock to Potgieter to draw his party's wagons back to the safety of the Rolong stronghold of Thaba Nchu, where the Sotho-Tswana chief offered the Boers food and protection. By January 1837, an alliance of 107 Boers, sixty Rolong, and forty Coloured men, organized as a commando under the leadership of Potgieter and Gert Maritz, attacked Mzilikazi's settlement at Mosega, which suffered heavy losses, and early in 1838 Mzilikazi fled north beyond the Limpopo (to current day Zimbabwe), never to return to Tranvaal. Andries Hendrik Potgieter

Andries Hendrik Potgieter

Andries Hendrik Potgieter, known as Hendrik Potgieter was a Voortrekker leader. He served as the first head of state of Potchefstroom from 1840 and 1845 and also as the first head of state of Zoutpansberg from 1845 to 1852.Potgieter was born in the Tarkastad district of the Cape Colony, the second...

, after the flight of the Ndebele, issued a proclamation in which he declared the country which Mzilikazi had abandoned and forfeited to the emigrant farmers, but also denying land rights to the Sotho-Tswana who had saved him and assisted in the defeat of the Mzilikazi and the Ndebele. After the Ndebele and Sotho-Tswana claims to the territory had been suppressed by the Boer political leadership, many Boer farmers trekked across the Vaal and occupied parts of the Transvaal, often near Sotho-Tswana villages, dividing the population up as forced laborers. Into these areas, still partly populated by remnants of the Ndebele and Sotho-Tswana, there was also a considerable immigration of members of the various Sotho-Tswana chiefdoms who had fled during the Difaqane.

The Boer entered into further conflicts with Mzilikazi from 1847–51, but his Ndebele warriors proved strong enough to repel the invaders. In 1852, the Boer government in Transvaal

South African Republic

The South African Republic , often informally known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer-ruled country in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century. Not to be confused with the present-day Republic of South Africa, it occupied the area later known as the South African...

entered into a peace with Mzilikazi. However, gold was discovered near Mthwakazi

Mthwakazi

Mthwakazi This word Mthwakazi is derived from the name of Queen Mu-Thwa, the first ruler of the Mthwakazi territory who ruled around 7,000 years ago...

in 1867 and the European powers became increasingly interested in the region.

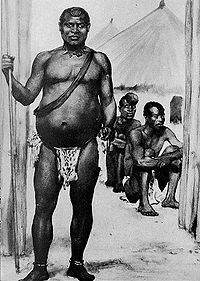

Mzilikazi died on 9 September 1868, near Bulawayo

Bulawayo

Bulawayo is the second largest city in Zimbabwe after the capital Harare, with an estimated population in 2010 of 2,000,000. It is located in Matabeleland, 439 km southwest of Harare, and is now treated as a separate provincial area from Matabeleland...

. His son, Lobengula

Lobengula

Lobengula Khumalo was the second and last king of the Ndebele people, usually pronounced Matabele in English. Both names, in the Sindebele language, mean "The men of the long shields", a reference to the Matabele warriors' use of the Zulu shield and spear.- Background :The Matabele were related to...

, became the king of Mthwakazi

Mthwakazi

Mthwakazi This word Mthwakazi is derived from the name of Queen Mu-Thwa, the first ruler of the Mthwakazi territory who ruled around 7,000 years ago...

. In exchange for wealth and arms, Lobengula granted several concessions to the British, the most prominent of which is the 1888 Rudd concession giving Cecil Rhodes exclusive mineral rights in much of the lands east of his main territory. Gold was already known to exist in nearby Mashonaland

Mashonaland

Mashonaland is a region in northern Zimbabwe. It is the home of the Shona people.Currently, Mashonaland is divided into three provinces, with a total population of about 3 million:* Mashonaland West* Mashonaland Central* Mashonaland East...

, so with the Rudd concession, Rhodes was able to obtain a royal charter to form the British South Africa Company

British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company was established by Cecil Rhodes through the amalgamation of the Central Search Association and the Exploring Company Ltd., receiving a royal charter in 1889...

in 1889.

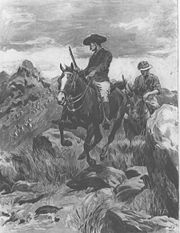

Pioneer Column

In 1890, Rhodes sent a group of settlers, known as the Pioneer ColumnPioneer Column

The Pioneer Column was a force raised by Cecil Rhodes and his British South Africa Company in 1890 and used in his efforts to annex the territory of Mashonaland, later part of Southern Rhodesia ....

, into Mashonaland. The 400+ man Pioneer Column was guided by the explorer and big game hunter Frederick Selous

Frederick Selous

Frederick Courteney Selous DSO was a British explorer, officer, hunter, and conservationist, famous for his exploits in south and east of Africa. His real-life adventures inspired Sir H. Rider Haggard to create the fictional Allan Quatermain character. Selous was also a good friend of Theodore...

and was officially designated the British South Africa Company Police (BSACP) accompanied by about 100 Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP). When they reached Harari Hill, they founded Fort Salisbury (now Harare

Harare

Harare before 1982 known as Salisbury) is the largest city and capital of Zimbabwe. It has an estimated population of 1,600,000, with 2,800,000 in its metropolitan area . Administratively, Harare is an independent city equivalent to a province. It is Zimbabwe's largest city and its...

). Rhodes had been distributing land to the settlers even before the royal charter, but the charter legitimized his further actions with the British government. By 1891 an Order-in-Council declared Matabeleland

Matabeleland

Modern day Matabeleland is a region in Zimbabwe divided into three provinces: Matabeleland North, Bulawayo and Matabeleland South. These provinces are in the west and south-west of Zimbabwe, between the Limpopo and Zambezi rivers. The region is named after its inhabitants, the Ndebele people...

, Mashonaland

Mashonaland

Mashonaland is a region in northern Zimbabwe. It is the home of the Shona people.Currently, Mashonaland is divided into three provinces, with a total population of about 3 million:* Mashonaland West* Mashonaland Central* Mashonaland East...

, and Bechuanaland a British protectorate. By 1892, the number of men in the force had decreased and the BSACP was replaced by a number of volunteer forces - the Mashonaland Horse, the Mashonaland Mounted Police and the Mashonaland Constabulary, and later additions of Salisbury Horse, Victoria Rangers, and Raaf's Rangers. The BSACP was later renamed the British South Africa Police

British South Africa Police

The British South Africa Police was the police force of the British South Africa Company of Cecil Rhodes which became the national police force of Southern Rhodesia and its successor after 1965, Rhodesia...

(BSAP) and this force stayed together for much of the 20th century.

Rhodes had a vested interest in the continued expansion of white settlements in the region, so now with the cover of a legal mandate, he used a brutal attack by Ndebele against the Shona near Fort Victoria (now Masvingo

Masvingo

Masvingo is a town in south-eastern Zimbabwe and the capital of Masvingo Province. The town is close to Great Zimbabwe, the national monument from which the country takes its name.- History :...

) in 1893 as a pretense for attacking the kingdom of Lobengula.

First Matabele War

Maxim gun

The Maxim gun was the first self-powered machine gun, invented by the American-born British inventor Sir Hiram Maxim in 1884. It has been called "the weapon most associated with [British] imperial conquest".-Functionality:...

, 2 seven-pounders, 1 Gardner gun, and 1 Hotchkiss. The Maxim guns took center stage and decimated the native force. Other African regiments were in the immediate vicinity, estimated at 5 000 men, however this force never took part in the fighting.

Lobengula had 80 000 spearmen and 20 000 riflemen, against fewer than 700 soldiers of the British South Africa Police, but the Ndebele warriors were no match against the British Maxim guns. Leander Starr Jameson

Leander Starr Jameson

Sir Leander Starr Jameson, 1st Baronet, KCMG, CB, , also known as "Doctor Jim", "The Doctor" or "Lanner", was a British colonial statesman who was best known for his involvement in the Jameson Raid....

immediately sent his troops to Bulawayo to try to capture Lobengula, but the king escaped and left Bulawayo in ruins behind him. The group of white settlers was sent to find Lobengula along the Shangani river, which they did, but nearly all members of this patrol were killed in battle on the Shangani river in Matabeleland in 1893. The incident achieved a lasting, prominent place in Rhodesian colonial history as the Shangani Patrol

Shangani Patrol

The Shangani Patrol was a group of white Rhodesian pioneer police officers killed in battle on the Shangani River in Matabeleland in 1893. The incident achieved a lasting, prominent place in Rhodesian colonial history.-Setting and Battle:...

and is roughly the British equivalent to Custer's Last Stand. But this was no victory for the Ndebele. Under somewhat mysterious circumstances, King Lobengula died in January 1894, and within a few short months the British South Africa Company controlled most of the Matabeleland and white settlers continued to arrive.

Jameson Raid

The Jameson RaidJameson Raid

The Jameson Raid was a botched raid on Paul Kruger's Transvaal Republic carried out by a British colonial statesman Leander Starr Jameson and his Rhodesian and Bechuanaland policemen over the New Year weekend of 1895–96...

(December 29, 1895 - January 2, 1896) was a raid on Paul Kruger's Transvaal Republic

South African Republic

The South African Republic , often informally known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer-ruled country in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century. Not to be confused with the present-day Republic of South Africa, it occupied the area later known as the South African...

carried out by Leander Starr Jameson and his Rhodesian and Bechuanaland policemen over the New Year weekend of 1895-96. It was intended to trigger an uprising by the primarily British expatriate workers (known as Uitlander

Uitlander

Uitlander, Afrikaans for "foreigner" , was the name given to expatriate migrant workers during the initial exploitation of the Witwatersrand gold fields in the Transvaal...

s) in the Transvaal

South African Republic

The South African Republic , often informally known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer-ruled country in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century. Not to be confused with the present-day Republic of South Africa, it occupied the area later known as the South African...

but failed to do so. The raid was ineffective and no uprising took place, but it did much to bring about the Second Boer War

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War was fought from 11 October 1899 until 31 May 1902 between the British Empire and the Afrikaans-speaking Dutch settlers of two independent Boer republics, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State...

and the Second Matabele War

Second Matabele War

The Second Matabele War, also known as the Matabeleland Rebellion and in Zimbabwe as the First Chimurenga, was fought in 1896–97 between the British troops and the Ndebele people....

.

First Chimurenga

The First ChimurengaChimurenga

Chimurenga is a Shona word for 'revolutionary struggle'. The word's modern interpretation has been extended to describe a struggle for human rights, political dignity and social justice, specifically used for the African insurrections against British colonial rule 1896–1897 and the guerrilla war...

is now celebrated in Zimbabwe as the First War of Independence, but it is best known in the anglosaxon world as the Second Matabele War. This conflict refers to the 1896-1897 Ndebele-Shona

Shona people

Shona is the name collectively given to two groups of people in the east and southwest of Zimbabwe, north eastern Botswana and southern Mozambique.-Shona Regional Classification:...

revolt against colonial rule by the British South Africa Company

British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company was established by Cecil Rhodes through the amalgamation of the Central Search Association and the Exploring Company Ltd., receiving a royal charter in 1889...

.

Mlimo, the Ndebele spiritual/religious leader, is credited with formenting much of the anger that led to this confrontation. He convinced the Ndebele and Shona that the white settlers (almost 4,000 strong by then) were responsible for the drought, locust plagues and the cattle disease rinderpest ravaging the country at the time. Mlimo's call to battle was well timed. Only a few months earlier, the British South Africa Company's Administrator General for Matabeleland, Leander Starr Jameson, had sent most of his troops and armaments to fight the Transvaal Republic in the ill-fated Jameson Raid. This left the country’s defenses in disarray. The Ndebele began their revolt in March 1896, and in June 1896 they were joined by the Shona.

The British South Africa Company immediately sent troops to suppress the Ndebele and the Shona, but it took months for the British to re-capture their major colonial fortifications under siege by native warriors. Mlimo was eventually assassinated in his temple in Matobo Hills by the American scout Frederick Russell Burnham

Frederick Russell Burnham

Frederick Russell Burnham, DSO was an American scout and world traveling adventurer known for his service to the British Army in colonial Africa and for teaching woodcraft to Robert Baden-Powell, thus becoming one of the inspirations for the founding of the international Scouting Movement.Burnham...

. Upon learning of the death of Mlimo, Cecil Rhodes boldly walked unarmed into the native's stronghold and persuaded the impi to lay down their arms. The First Chimurenga thus ended on October 1897 and Matabeleland and Mashonaland

Mashonaland

Mashonaland is a region in northern Zimbabwe. It is the home of the Shona people.Currently, Mashonaland is divided into three provinces, with a total population of about 3 million:* Mashonaland West* Mashonaland Central* Mashonaland East...

were later renamed Rhodesia.

Second Chimurenga

Rhodesia

Rhodesia , officially the Republic of Rhodesia from 1970, was an unrecognised state located in southern Africa that existed between 1965 and 1979 following its Unilateral Declaration of Independence from the United Kingdom on 11 November 1965...

and to the de-facto independence of Zimbabwe. It was a conflict between the minority white settler government of Ian Smith

Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith GCLM ID was a politician active in the government of Southern Rhodesia, the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, Rhodesia, Zimbabwe Rhodesia and Zimbabwe from 1948 to 1987, most notably serving as Prime Minister of Rhodesia from 13 April 1964 to 1 June 1979...

Rhodesian Front

Rhodesian Front

The Rhodesian Front was a political party in Southern Rhodesia when the country was under white minority rule. Led first by Winston Field, and, from 1964, by Ian Smith, the Rhodesian Front was the successor to the Dominion Party, which was the main opposition party in Southern Rhodesia during the...

and the African nationalists of the Patriotic Front (Zimbabwe)

Patriotic Front (Zimbabwe)

The Patriotic Front in Zimbabwe was a coalition of two communist parties: the Zimbabwe African Peoples Union and the Zimbabwe African National Union which had worked together to fight against white minority rule in Rhodesia....

alliance of ZANU (mainly Shona

Shona people

Shona is the name collectively given to two groups of people in the east and southwest of Zimbabwe, north eastern Botswana and southern Mozambique.-Shona Regional Classification:...

) and ZAPU (mainly Ndebele) movements, led by Robert Mugabe

Robert Mugabe

Robert Gabriel Mugabe is the President of Zimbabwe. As one of the leaders of the liberation movement against white-minority rule, he was elected into power in 1980...

and Joshua Nkomo

Joshua Nkomo

Joshua Mqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo was the leader and founder of the Zimbabwe African People's Union and a member of the Kalanga tribe...

respectively.

Overview

With the breakup of Federation of Rhodesia and NyasalandFederation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland

The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, also known as the Central African Federation , was a semi-independent state in southern Africa that existed from 1953 to the end of 1963, comprising the former self-governing colony of Southern Rhodesia and the British protectorates of Northern Rhodesia,...

in 1964 the army underwent a large- scale reorganization by the British. In 1965, Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was the name of the British colony situated north of the Limpopo River and the Union of South Africa. From its independence in 1965 until its extinction in 1980, it was known as Rhodesia...

took matters into its own hands in 1965 with a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI). From April 1966 onwards groups of Soviet-supported guerrillas infiltrated Rhodesia from neighbouring Zambia

Zambia

Zambia , officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. The neighbouring countries are the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the north, Tanzania to the north-east, Malawi to the east, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Namibia to the south, and Angola to the west....

in steadily increasing numbers, with the goal of overthrowing the white-rule government, but the Second Chumerenga is generally considered to have started in earnest on December 21, 1972 when an attack took place on a farm in the Centenary District, with further attacks on other farms in the following days.

As the guerrilla activity increased in 1973 "Operation Hurricane" started and the military prepared itself for war. During 1974 a major effort by the security forces resulted in many guerrillas being killed and the number inside the country reduced to less than 100. However, a second front in the Second Chumerenga emerged in 1974 when the Portugal

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

withdrew from its colonly of Mozambique

Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique , is a country in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west and Swaziland and South Africa to the southwest...

.

In 1976 Operations "Thrasher" and "Repulse" started in order to contain the ever-increasing influx of guerrillas. At the same time rivalry between the two main guerrilla factions increased and resulted in open fighting in the training camps in Tanzania

Tanzania

The United Republic of Tanzania is a country in East Africa bordered by Kenya and Uganda to the north, Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west, and Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique to the south. The country's eastern borders lie on the Indian Ocean.Tanzania is a state...

, with over 600 deaths. The Soviets increased their influence and began to take a more active role in the training and control of the ZIPRA guerrillas. Perhaps too late, the Rhodesians decided to take the war to the enemy, and cross-border operations, which had started in 1976 with a raid on a major base in Mozambique in which the Rhodesians had killed over 1,200 guerrillas and captured huge amounts of weapons, were stepped up. In 1977, Operation "Dingo"

Operation Dingo

Operation Dingo, also known as the Chimoio massacre was a major raid conducted by the Rhodesian Security Forces against the ZANLA headquarters of Robert Mugabe at Chimoio and a smaller camp at Tembue in Mozambique from November 23–25, 1977...

was a major raid on large guerrilla camps such as Chimoio

Chimoio

Chimoio is the capital of Manica Province in Mozambique. It is the fifth-largest city in Mozambique.Chimoio's name under Portuguese administration was Vila Pery. Vila Pery developed under Portuguese rule as an important agricultural and textiles centre.The town lies on the railway line from Beira...

and Tembue in Moazambique which resulted in thousands of guerrilla deaths and the capture of supplies sorely needed by the Rhodesians.

In 1978 the Rhodesian Air Force launched the daring "Green Leader" attack on a ZIPRA camp outside Lusaka, the Rhodesian fighters completely taking over Zambian air space for the duration of the raid. In September of the same year, the guerrillas again took the offensive by shooting down a Rhodesian airliner with a SAM-7 missile. Eighteen civilians who survived the crash were subsequently massacred at the crash site by ZIPRA guerrillas, increasing calls for massive retaliation by the Rhodesian security forces. In 1979 as the war increased even more in intensity.

Rhodesian Light Infantry

The Rhodesian Light InfantryRhodesian Light Infantry

The 1st Battalion, The Rhodesian Light Infantry, commonly the Rhodesian Light Infantry , was a regiment formed in 1961 at Brady Barracks, Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia as a light infantry unit within the army of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland...

, or RLI, was at the forefront of the Second Chimurenga. It was a regular army infantry regiment in the Rhodesian army, composed only of white recruits, The battalion was organised into four company size sub-units called 'Commandos'; 1, 2, 3 and Support Commando. In theory each commando had five 'Troops' (platoon size structures), though much of the time there were only four. The average fighting strength of a Commando was about 70. The rank structure was; Trooper, Lance-corporal, Corporal, Sergeant etc. All ranks were called 'troopies' by the Rhodesian media.

The RLI's most characteristic deployment was the 'fire force' reaction operation. This was an operational assault or response composed of, usually, a first wave of 32 troopers carried to the scene by three helicopters and one DC-3 Dakota (called "Dak"), with a command/gun helicopter and a light attack-aircraft in support. The latter was a Cessna Skymaster

Cessna Skymaster

The Cessna Skymaster is a United States twin-engine civil utility aircraft built in a push-pull configuration. Its engines are mounted in the nose and rear of its pod-style fuselage. Twin booms extend aft of the wings to the vertical stabilizers, with the rear engine between them. The horizontal...

, usually armed with two 30 mm rocket pods and two small napalm

Napalm

Napalm is a thickening/gelling agent generally mixed with gasoline or a similar fuel for use in an incendiary device, primarily as an anti-personnel weapon...

-bombs (made in Rhodesia and called 'Fran-tan').

The RLI became extremely adept at this type of military operation and the battalion killed or captured around 3000 of the enemy (the vast majority being ZANLA - Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army) in the last three years of the war, whilst losing less than three hundred killed and wounded (not counting those casualties incurred in patrolling or external ops).

In addition to the fire force, the four Commandos were often used in patrolling actions, mostly inside Rhodesia but sometimes in Zambia

Zambia

Zambia , officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. The neighbouring countries are the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the north, Tanzania to the north-east, Malawi to the east, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Namibia to the south, and Angola to the west....

and Mozambique

Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique , is a country in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west and Swaziland and South Africa to the southwest...

. In these operations troopies were required to carry well over 100 lbs of equipment for five to tens days for one patrol and come back and repeat, for weeks, sometimes months. Also, they participated in many attacks on enemy camps in above countries. In a few of these attacks most or all of the battalion was involved.

The First Battalion Rhodesian Light Infantry was originally formed within the army of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland in 1961 in Bulawayo

Bulawayo

Bulawayo is the second largest city in Zimbabwe after the capital Harare, with an estimated population in 2010 of 2,000,000. It is located in Matabeleland, 439 km southwest of Harare, and is now treated as a separate provincial area from Matabeleland...

. The battalion's nucleus came from the short-lived Number One Training Unit, which had been raised to provide personnel for a white infantry battalion as well as for C Squadron 22 (Rhodesian) SAS

C Squadron 22 (Rhodesian) SAS

The Rhodesian Special Air Service or Rhodesian SAS refers to:*C Squadron, Special Air Service Regiment *"C" Squadron Special Air Service *1 Special Air Service Regiment...

and the Rhodesian Armoured Car Regiment Selous Scouts (not the Selous Scout special forces regiment of the same name).

Selous Scouts

During this time period the Selous ScoutsSelous Scouts

The Selous Scouts was a special forces regiment of the Rhodesian Army, which operated from 1973 until the introduction of majority rule in 1980. It was named after British explorer Frederick Courteney Selous , and their motto was pamwe chete, which, in the Shona language, roughly means "all...

, operated as special forces regiment of the Rhodesia

Rhodesia

Rhodesia , officially the Republic of Rhodesia from 1970, was an unrecognised state located in southern Africa that existed between 1965 and 1979 following its Unilateral Declaration of Independence from the United Kingdom on 11 November 1965...

n Army. They were named after British explorer Frederick Courteney Selous (1851–1917), and their motto was pamwe chete, which translated from Shona

Shona language

Shona is a Bantu language, native to the Shona people of Zimbabwe and southern Zambia; the term is also used to identify peoples who speak one of the Shona language dialects: Zezuru, Karanga, Manyika, Ndau and Korekore...

means "all together", "together only" or "forward together". The charter of the Selous Scouts directed "the clandestine elimination of terrorists/terrorism both within and without the country."

The Selous Scouts were racial-integrated unit (approx. 70% black soldiers) which conducted a highly successful clandestine war against the guerrillas by posing as guerrillas themselves. Their unrivalled tracking abilities, survival and COIN skills made them one of the most feared of the army units by enemy. The unit was responsible for 68% of all enemy casualties within the borders of Rhodesia.

British South Africa Police

The BSAP, a unit in existence since the 1890s, formed an important part of the white minority government's fight against black nationalist guerrillas. The force formed a riot unit; a tracker combat team (later renamed the Police Anti-Terrorist Unit or PATU); an Urban Emergency Unit and a Marine Division, and from 1973 offered places to white conscripts as part of Rhodesia's national service scheme. Until the late 1970s, black Rhodesians were prevented from holding ranks higher than Sub-Inspector in the BSAP, and only white Rhodesians could gain commissioned rank.Patriotic Front

The Patriotic Front (PF) was originally formed in 1976 as a political and military alliance between ZAPU and ZANU during the war against white minority rule. Both movements contributed their respective military forces: ZAPU's military wing was known as Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRAZIPRA

Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army was the armed wing of the Zimbabwe African People's Union, a political party in Rhodesia. It participated in the Second Chimurenga against white minority rule in the former Rhodesia....

) which operated mainly from Zambia and somewhat in Angola

Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola , is a country in south-central Africa bordered by Namibia on the south, the Democratic Republic of the Congo on the north, and Zambia on the east; its west coast is on the Atlantic Ocean with Luanda as its capital city...

, and ZANU's guerrillas where known as Zimbabwe National African Liberation Army (ZANLA) which formed in 1965 in Tanzania, but operated mainly from camps around Lusaka

Lusaka

Lusaka is the capital and largest city of Zambia. It is located in the southern part of the central plateau, at an elevation of about 1,300 metres . It has a population of about 1.7 million . It is a commercial centre as well as the centre of government, and the four main highways of Zambia head...

, Zambia and later from Mozambique. Objective of the Patriotic Front was to overthrow the white minority regime by means of political pressure and military force.

End of Second Chimurenga

Lancaster House Agreement

The negotiations which led to the Lancaster House Agreement brought independence to Rhodesia following Ian Smith’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence in 1965. The Agreement covered the Independence Constitution, pre-independence arrangements, and a ceasefire...

, at the behest of both South Africa

South Africa

The Republic of South Africa is a country in southern Africa. Located at the southern tip of Africa, it is divided into nine provinces, with of coastline on the Atlantic and Indian oceans...

(its major backer) and the US, multi-ethnic elections were subsequently held in early 1980. Britain recognised this new government and the newly, internationally recognised, independent country was renamed as Zimbabwe. A nucleus of former RLI personnel remained to train and form the First Zimbabwe Commando

Commando

In English, the term commando means a specific kind of individual soldier or military unit. In contemporary usage, commando usually means elite light infantry and/or special operations forces units, specializing in amphibious landings, parachuting, rappelling and similar techniques, to conduct and...

Battalion of the Zimbabwe National Army

Zimbabwe National Army

The Zimbabwe National Army is the land warfare branch of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces. The ZNA currently has an active duty strength of 30,000.-History:...

, however, the RLI regiment itself was disbanded in 1980. The Selous Scouts were also disbanded in 1980, but many of its soldiers travelled south to join the Apartheid South African Defence Force

South African Defence Force

The South African Defence Force was the South African armed forces from 1957 until 1994. The former Union Defence Force was renamed to the South African Defence Force in the Defence Act of 1957...

, where they joined 5 Reconnaissance Commando

South African Special Forces Brigade

The South African Special Forces Brigade is the only Special Forces unit of the South African National Defence Force ....

. The BSAP, which at the time of Mugabe's victory consisted of approximately 11,000 regulars (about 60% black) and almost 35,000 reservists, of whom the overwhelming majority were white, was renamed the Zimbabwe Republic Police

Zimbabwe Republic Police

The Zimbabwe Republic Police is the national police force of Zimbabwe, known until July 1980 as the British South Africa Police. -Structure:...

and followed an official policy of "Africanisation", in which senior white officers were retired and their positions filled by black officers.

Third Chimurenga

Following majority rule elections, the rivalry that had been fermenting between ZAPU and ZANU erupted, with guerrilla activity starting again in the Matabeleland provinces (south-western Zimbabwe). Armed resistance in Matabeleland was met with bloody government repression. At least 20,000 Matabele died in the ensuing near-genocidal massacres, perpetrated by an elite, communist-trained brigade, known in Zimbabwe as the GukurahundiGukurahundi

The Gukurahundi refers to the suppression by Zimbabwe's 5th Brigade in the predominantly Ndebele regions of Zimbabwe most of whom were supporters of Joshua Nkomo. A few hundred disgruntled former ZIPRA combatants waged armed banditry against the civilians in Matabeleland, and destroyed government...

. A peace accord was negotiated and on December 30, 1987 Mugabe became head of state after changing the constitution to usher in his vision of a presidential regime. On December 19, 1989 ZAPU merged with ZANU under the name ZANU-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF).

Land reform in Zimbabwe

Land reform in Zimbabwe officially began in 1979 with the signing of the Lancaster House Agreement, an effort to more equitably distribute land between the historically disenfranchised blacks and the minority-whites who ruled Zimbabwe from 1890 to 1979...

the "Third Chimurenga". The beginning of the "Third Chimurenga" is often attributed to the need to distract Zimbabwean electorate from the poorly conceived war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is a state located in Central Africa. It is the second largest country in Africa by area and the eleventh largest in the world...

and deepening economic problems blamed on graft and ineptitude in the ruling party.

The opposition briefly used the term to describe Zimbabwe's current struggles aimed at removing the ZANU government, resolving the Land Question, the establishment of democracy

Democracy

Democracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

, rebuilding the rule of law and good governance, as well as the eradication of corruption

Political corruption

Political corruption is the use of legislated powers by government officials for illegitimate private gain. Misuse of government power for other purposes, such as repression of political opponents and general police brutality, is not considered political corruption. Neither are illegal acts by...

in Government. The term is no longer in vogue amongst Zimbabwe's urban population and lacks the gravitas it once had so was dropped from the opposition's lexicon.

Modern Zimbabwe

In 1999, the Government of Zimbabwe sent a sizeable military force into the Democratic Republic of CongoDemocratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is a state located in Central Africa. It is the second largest country in Africa by area and the eleventh largest in the world...

to support the government of President Laurent Kabila during the Second Congo War

Second Congo War

The Second Congo War, also known as Coltan War and the Great War of Africa, began in August 1998 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo , and officially ended in July 2003 when the Transitional Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo took power; however, hostilities continue to this...

. Those forces were largely withdrawn in 2002.