Monmouth Rebellion

Encyclopedia

James II of England

James II & VII was King of England and King of Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII, from 6 February 1685. He was the last Catholic monarch to reign over the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland...

, who had become King of England, King of Scots and King of Ireland

King of Ireland

A monarchical polity has existed in Ireland during three periods of its history, finally ending in 1801. The designation King of Ireland and Queen of Ireland was used during these periods...

at the death of his elder brother Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

on 6 February 1685. James II was a Roman Catholic, and some Protestants

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

under his rule opposed his kingship. James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth

James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth

James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, 1st Duke of Buccleuch, KG, PC , was an English nobleman. Originally called James Crofts or James Fitzroy, he was born in Rotterdam in the Netherlands, the eldest illegitimate son of Charles II and his mistress, Lucy Walter...

, an illegitimate son of Charles II, claimed to be rightful heir to the throne and attempted to displace James II.

The rebellion ended with the defeat of Monmouth's forces at the Battle of Sedgemoor

Battle of Sedgemoor

The Battle of Sedgemoor was fought on 6 July 1685 and took place at Westonzoyland near Bridgwater in Somerset, England.It was the final battle of the Monmouth Rebellion and followed a series of skirmishes around south west England between the forces of James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth and the...

on 6 July 1685. Monmouth was executed for treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

on 15 July, and many of his supporters were executed or transported

Penal transportation

Transportation or penal transportation is the deporting of convicted criminals to a penal colony. Examples include transportation by France to Devil's Island and by the UK to its colonies in the Americas, from the 1610s through the American Revolution in the 1770s, and then to Australia between...

in the "Bloody Assizes

Bloody Assizes

The Bloody Assizes were a series of trials started at Winchester on 25 August 1685 in the aftermath of the Battle of Sedgemoor, which ended the Monmouth Rebellion in England....

" of Judge Jeffreys

George Jeffreys, 1st Baron Jeffreys

George Jeffreys, 1st Baron Jeffreys of Wem, PC , also known as "The Hanging Judge", was an English judge. He became notable during the reign of King James II, rising to the position of Lord Chancellor .- Early years and education :Jeffreys was born at the family estate of Acton Hall, near Wrexham,...

.

Duke of Monmouth

Monmouth was an illegitimate son of Charles II. There had been rumours that Charles had married Monmouth's mother, Lucy Walter

Lucy Walter

Lucy Walter or Lucy Barlow was a mistress of King Charles II of England and mother of James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth. She is believed to have been born in 1630 or a little later at Roch Castle near Haverfordwest, Wales into a family of middling gentry...

, but no evidence was forthcoming, and Charles always said that he only had one wife, Catherine of Braganza

Catherine of Braganza

Catherine of Braganza was a Portuguese infanta and queen consort of England, Scotland and Ireland as the wife of King Charles II.She married the king in 1662...

. That marriage produced no surviving children.

Monmouth was a Protestant. He had been appointed Commander-in-Chief of the English Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

by his father in 1672 and Captain-General in 1678, enjoying some successes in the Netherlands in the Third Anglo-Dutch War

Third Anglo-Dutch War

The Third Anglo–Dutch War or Third Dutch War was a military conflict between England and the Dutch Republic lasting from 1672 to 1674. It was part of the larger Franco-Dutch War...

.

An attempt was made in 1681 to pass the Exclusion Bill

Exclusion Bill

The Exclusion Crisis ran from 1678 through 1681 in the reign of Charles II of England. The Exclusion Bill sought to exclude the king's brother and heir presumptive, James, Duke of York, from the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland because he was Roman Catholic...

, an Act of Parliament

Act of Parliament

An Act of Parliament is a statute enacted as primary legislation by a national or sub-national parliament. In the Republic of Ireland the term Act of the Oireachtas is used, and in the United States the term Act of Congress is used.In Commonwealth countries, the term is used both in a narrow...

to exclude James Stuart

James II of England

James II & VII was King of England and King of Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII, from 6 February 1685. He was the last Catholic monarch to reign over the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland...

, Charles II's brother, from the succession and substitute Monmouth, but Charles outmanoeuvred his opponents and dissolved Parliament for the final time. After the Rye House Plot

Rye House Plot

The Rye House Plot of 1683 was a plan to assassinate King Charles II of England and his brother James, Duke of York. Historians vary in their assessment of the degree to which details of the conspiracy were finalized....

to assassinate both Charles and James, Monmouth exiled himself to Holland, and gathered supporters in The Hague

The Hague

The Hague is the capital city of the province of South Holland in the Netherlands. With a population of 500,000 inhabitants , it is the third largest city of the Netherlands, after Amsterdam and Rotterdam...

.

So long as Charles II remained on the throne, Monmouth was content to live a life of pleasure in Holland, while still hoping to accede peaceably to the throne. The accession of James II put an end to these hopes. Prince William of Orange

William III of England

William III & II was a sovereign Prince of Orange of the House of Orange-Nassau by birth. From 1672 he governed as Stadtholder William III of Orange over Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel of the Dutch Republic. From 1689 he reigned as William III over England and Ireland...

, although also a Protestant, was bound to James by treaties and could not accommodate a rival claimant.

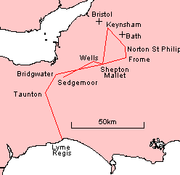

From Lyme Regis to Sedgemoor

In May 1685, Monmouth set sail for South West EnglandSouth West England

South West England is one of the regions of England defined by the Government of the United Kingdom for statistical and other purposes. It is the largest such region in area, covering and comprising Bristol, Gloucestershire, Somerset, Dorset, Wiltshire, Devon, Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly. ...

, a strongly Protestant region, with three small ships, four light field guns and 1500 muskets. He landed with 82 supporters, including Lord Grey of Warke

Ford Grey, 1st Earl of Tankerville

Ford Grey, 1st Earl of Tankerville , 1st Viscount Glendale, and 3rd Baron Grey of Warke, was a British nobleman and statesman. He was the son of Ralph Grey, 2nd Baron Grey of Werke and Catherine Ford, daughter of Sir Edward Ford of Harting in West Sussex. He was baptized the day of his birth at...

, and gathered about 300 men at Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis is a coastal town in West Dorset, England, situated 25 miles west of Dorchester and east of Exeter. The town lies in Lyme Bay, on the English Channel coast at the Dorset-Devon border...

in Dorset

Dorset

Dorset , is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The county town is Dorchester which is situated in the south. The Hampshire towns of Bournemouth and Christchurch joined the county with the reorganisation of local government in 1974...

on 11 June. King James was soon warned of Monmouth's arrival; two customs officers from Lyme arrived in London on 13 June having ridden 200 miles (322 km) post haste.

Other important members of the rebellion were:

- Robert Ferguson. A fanatical Scottish Presbyterian Minister, he was also known as "the plotter". It was Ferguson who drew up Monmouth's proclamation, and he who was most in favour of Monmouth being crowned King.

- Thomas Hayward Dare. Dare was a goldsmith

Goldsmith

A goldsmith is a metalworker who specializes in working with gold and other precious metals. Since ancient times the techniques of a goldsmith have evolved very little in order to produce items of jewelry of quality standards. In modern times actual goldsmiths are rare...

from Taunton

Taunton

Taunton is the county town of Somerset, England. The town, including its suburbs, had an estimated population of 61,400 in 2001. It is the largest town in the shire county of Somerset....

and a Whig politician, a man of considerable wealth and influence who had been jailed during a political campaign calling for a new parliament. He was also fined the huge sum of £5,000 for uttering 'seditious' words. After his release from gaol, he fled to Holland and became the paymaster general to the Rebellion.

- The Duke of Argyll

Duke of Argyll

Duke of Argyll is a title, created in the Peerage of Scotland in 1701 and in the Peerage of the United Kingdom in 1892. The Earls, Marquesses, and Dukes of Argyll were for several centuries among the most powerful, if not the most powerful, noble family in Scotland...

. Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll

Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll

Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll was a Scottish peer.He was born in 1629 in Dalkeith, Scotland, the son of Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll....

was to lead the Scottish revolt and had already been involved in one unsuccessful attempt, known as the Rye House Plot

Rye House Plot

The Rye House Plot of 1683 was a plan to assassinate King Charles II of England and his brother James, Duke of York. Historians vary in their assessment of the degree to which details of the conspiracy were finalized....

of 1683.

Instead of marching on London, Monmouth marched north towards Somerset

Somerset

The ceremonial and non-metropolitan county of Somerset in South West England borders Bristol and Gloucestershire to the north, Wiltshire to the east, Dorset to the south-east, and Devon to the south-west. It is partly bounded to the north and west by the Bristol Channel and the estuary of the...

, and on 14 June clashed with the Dorset Militia at Bridport

Bridport

Bridport is a market town in Dorset, England. Located near the coast at the western end of Chesil Beach at the confluence of the River Brit and its Asker and Simene tributaries, it originally thrived as a fishing port and rope-making centre...

. Many of the militiamen deserted and joined Monmouth's army, before he fought another skirmish on the 15th at Axminster

Axminster

Axminster is a market town and civil parish on the eastern border of Devon in England. The town is built on a hill overlooking the River Axe which heads towards the English Channel at Axmouth, and is in the East Devon local government district. It has a population of 5,626. The market is still...

. The recruits joined his disorganised force, which was now around 6,000, mostly nonconformist, artisan

Artisan

An artisan is a skilled manual worker who makes items that may be functional or strictly decorative, including furniture, clothing, jewellery, household items, and tools...

s and farmer workers armed with farm tools (such as pitchfork

Pitchfork

A pitchfork is an agricultural tool with a long handle and long, thin, widely separated pointed tines used to lift and pitch loose material, such as hay, leaves, grapes, dung or other agricultural materials. Pitchforks typically have two or three tines...

s): one famous supporter was the young Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe , born Daniel Foe, was an English trader, writer, journalist, and pamphleteer, who gained fame for his novel Robinson Crusoe. Defoe is notable for being one of the earliest proponents of the novel, as he helped to popularise the form in Britain and along with others such as Richardson,...

.

Monmouth declared himself King and was crowned in Chard

Chard, Somerset

Chard is a town and civil parish in the Somerset county of England. It lies on the A30 road near the Devon border, south west of Yeovil. The parish has a population of approximately 12,000 and, at an elevation of , it is the southernmost and highest town in Somerset...

and was the subject of more coronations in Taunton

Taunton

Taunton is the county town of Somerset, England. The town, including its suburbs, had an estimated population of 61,400 in 2001. It is the largest town in the shire county of Somerset....

on 20 June 1685, when Taunton Corporation was made to witness the event at swords point outside the White Hart Inn. This was done to encourage the support of the country gentry. He then continued north, via Shepton Mallet

Shepton Mallet

Shepton Mallet is a small rural town and civil parish in the Mendip district of Somerset in South West England. Situated approximately south of Bristol and east of Wells, the town is estimated to have a population of 9,700. It contains the administrative headquarters of Mendip District Council...

(23 June). Meanwhile, the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

captured Monmouth's ships, cutting off any hope of an escape back to the continent should he be defeated.

Pensford

Pensford is a village in the civil parish of Publow and Pensford in Somerset, England. It lies in the Chew Valley south of Bristol and west of Bath...

, and the next day arrived in Keynsham

Keynsham

Keynsham is a town and civil parish between Bristol and Bath in Somerset, south-west England. It has a population of 15,533.It was listed in the Domesday Book as Cainesham, which is believed to mean the home of Saint Keyne....

, intending to attack the city of Bristol

Bristol

Bristol is a city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, with an estimated population of 433,100 for the unitary authority in 2009, and a surrounding Larger Urban Zone with an estimated 1,070,000 residents in 2007...

(at the time was the second largest and second most important city after London). However, he found the city had been occupied by Henry Somerset, 1st Duke of Beaufort

Henry Somerset, 1st Duke of Beaufort

Henry Somerset, 1st Duke of Beaufort, KG, PC was an English peer. He was styled Lord Herbert from 1646 until 3 April 1667, when he succeeded his father as 3rd Marquess of Worcester....

, and the men of the Gloucester Militia. There were inconclusive skirmishes with a force of Life Guards

Life Guards (British Army)

The Life Guards is the senior regiment of the British Army and with the Blues and Royals, they make up the Household Cavalry.They originated in the four troops of Horse Guards raised by Charles II around the time of his restoration, plus two troops of Horse Grenadier Guards which were raised some...

commanded by Louis de Duras

Louis de Duras, 2nd Earl of Feversham

Louis de Duras, 2nd Earl of Feversham KG was a French nobleman who became Earl of Feversham in Stuart England.Born in France, he was marquis de Blanquefort and sixth son of Guy Aldonce , Marquis of Duras and Count of Rozan, from the noble Durfort family...

, 2nd Earl of Feversham

Earl of Feversham

Earl of Feversham is a title that has been created three times , once in the Peerage of England, once in the Peerage of Great Britain and once in the Peerage of the United Kingdom...

(an elderly nephew of Turenne, who had spent some time in English service and later became a Knight of the Garter). Monmouth then moved towards Bath, which had also been occupied by Royalist troops, He camped in Philips Norton (now Norton St Philip

Norton St Philip

Norton St Philip is a village in Somerset, England, located between the City of Bath and the town of Frome. The village is in the district of Mendip, and the parliamentary constituency of Somerton and Frome....

), where his forces were attacked on the 27th June by Feversham's forces. Monmouth then marched overnight to Frome

Frome

Frome is a town and civil parish in northeast Somerset, England. Located at the eastern end of the Mendip Hills, the town is built on uneven high ground, and centres around the River Frome. The town is approximately south of Bath, east of the county town, Taunton and west of London. In the 2001...

, heading for Warminster

Warminster

Warminster is a town in western Wiltshire, England, by-passed by the A36, and near Frome and Westbury. It has a population of about 17,000. The River Were runs through the town and can be seen running through the middle of the town park. The Minster Church of St Denys sits on the River Were...

.

Monmouth was counting on a rebellion in Scotland, led by Archibald Campbell

Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll

Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll was a Scottish peer.He was born in 1629 in Dalkeith, Scotland, the son of Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll....

, 9th Earl of Argyll, weakening the King's support and army. Argyll landed at Campbeltown

Campbeltown

Campbeltown is a town and former royal burgh in Argyll and Bute, Scotland. It lies by Campbeltown Loch on the Kintyre peninsula. Originally known as Kinlochkilkerran , it was renamed in the 17th century as Campbell's Town after Archibald Campbell was granted the site in 1667...

on 20 May and spent some days raising a small army of supporters, but was unable to hold them together while marching through the lowlands towards Glasgow

Glasgow

Glasgow is the largest city in Scotland and third most populous in the United Kingdom. The city is situated on the River Clyde in the country's west central lowlands...

. Argyll and his few remaining companions were captured at Inchinnan

Inchinnan

Inchinnan is a small village in Renfrewshire, Scotland. The village is located on the main A8 road between Renfrew and Greenock, just southeast of the town of Erskine.-History:...

on 19 June, and he was taken to Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

, where he was executed on 30 June. Expected rebellions in Cheshire

Cheshire

Cheshire is a ceremonial county in North West England. Cheshire's county town is the city of Chester, although its largest town is Warrington. Other major towns include Widnes, Congleton, Crewe, Ellesmere Port, Runcorn, Macclesfield, Winsford, Northwich, and Wilmslow...

and East Anglia

East Anglia

East Anglia is a traditional name for a region of eastern England, named after an ancient Anglo-Saxon kingdom, the Kingdom of the East Angles. The Angles took their name from their homeland Angeln, in northern Germany. East Anglia initially consisted of Norfolk and Suffolk, but upon the marriage of...

also failed to materialise.

The morale of Monmouth's forces started to collapse as news of the setback in Scotland arrived on 28 June, while the makeshift army was camped in Frome

Frome

Frome is a town and civil parish in northeast Somerset, England. Located at the eastern end of the Mendip Hills, the town is built on uneven high ground, and centres around the River Frome. The town is approximately south of Bath, east of the county town, Taunton and west of London. In the 2001...

.

The rebels got as far as Trowbridge

Trowbridge

Trowbridge is the county town of Wiltshire, England, situated on the River Biss in the west of the county, approximately 12 miles southeast of Bath, Somerset....

, but royalist forces cut off the route and Monmouth turned back towards Somerset through Shepton Mallet

Shepton Mallet

Shepton Mallet is a small rural town and civil parish in the Mendip district of Somerset in South West England. Situated approximately south of Bristol and east of Wells, the town is estimated to have a population of 9,700. It contains the administrative headquarters of Mendip District Council...

, arriving in Wells

Wells

Wells is a cathedral city and civil parish in the Mendip district of Somerset, England, on the southern edge of the Mendip Hills. Although the population recorded in the 2001 census is 10,406, it has had city status since 1205...

on 1 July. The soldiers damaged the West front of Wells Cathedral

Wells Cathedral

Wells Cathedral is a Church of England cathedral in Wells, Somerset, England. It is the seat of the Bishop of Bath and Wells, who lives at the adjacent Bishop's Palace....

, tearing lead from the roof to make bullets, breaking the windows, smashing the organ and the furnishings, and for a time stabling their horses in the nave.

Eventually Monmouth was pushed back to the Somerset Levels

Somerset Levels

The Somerset Levels, or the Somerset Levels and Moors as they are less commonly but more correctly known, is a sparsely populated coastal plain and wetland area of central Somerset, South West England, between the Quantock and Mendip Hills...

, where Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great was King of Wessex from 871 to 899.Alfred is noted for his defence of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of southern England against the Vikings, becoming the only English monarch still to be accorded the epithet "the Great". Alfred was the first King of the West Saxons to style himself...

had found refuge in his conflicts with the Vikings). Becoming hemmed in at Bridgwater

Bridgwater

Bridgwater is a market town and civil parish in Somerset, England. It is the administrative centre of the Sedgemoor district, and a major industrial centre. Bridgwater is located on the major communication routes through South West England...

on 3 July, he ordered his troops to fortify the town.

Battle of Sedgemoor

Monmouth was finally defeated by Feversham (with Lord ChurchillJohn Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough

John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, Prince of Mindelheim, KG, PC , was an English soldier and statesman whose career spanned the reigns of five monarchs through the late 17th and early 18th centuries...

, later Duke of Marlborough, his second in command) on 6 July at the Battle of Sedgemoor

Battle of Sedgemoor

The Battle of Sedgemoor was fought on 6 July 1685 and took place at Westonzoyland near Bridgwater in Somerset, England.It was the final battle of the Monmouth Rebellion and followed a series of skirmishes around south west England between the forces of James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth and the...

. Monmouth had risked a night attack, but surprise was lost when a musket was discharged. His untrained supporters were quickly defeated by the professionals, and hundreds were cut down by cannon- and musket-fire.

The battle of Sedgemoor is often referred to as the last battle fought on English soil, but this depends on the definition of battle, for which there are different interpretations

Pitched battle

A pitched battle is a battle where both sides choose to fight at a chosen location and time and where either side has the option to disengage either before the battle starts, or shortly after the first armed exchanges....

. Other contenders for the title of last English battle include: the Battle of Preston

Battle of Preston (1715)

The Battle of Preston , also referred to as the Preston Fight, was fought during the Jacobite Rising of 1715 ....

in Lancashire

Lancashire

Lancashire is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in the North West of England. It takes its name from the city of Lancaster, and is sometimes known as the County of Lancaster. Although Lancaster is still considered to be the county town, Lancashire County Council is based in Preston...

, which was fought on 14 November 1715, during the First Jacobite Rebellion

Jacobitism

Jacobitism was the political movement in Britain dedicated to the restoration of the Stuart kings to the thrones of England, Scotland, later the Kingdom of Great Britain, and the Kingdom of Ireland...

; and the Second Jacobite Rebellion's

Jacobitism

Jacobitism was the political movement in Britain dedicated to the restoration of the Stuart kings to the thrones of England, Scotland, later the Kingdom of Great Britain, and the Kingdom of Ireland...

minor engagement at Clifton Moor

Clifton Moor Skirmish

The Clifton Moor Skirmish took place between forces of the British Hanoverian government and Jacobite rebels on 19 December 1745. Since the commander of the British forces, the Duke of Cumberland, was aware of the Jacobite presence in Derby, the Jacobite leader Prince Charles Edward Stuart decided...

, near Penrith in Cumbria

Cumbria

Cumbria , is a non-metropolitan county in North West England. The county and Cumbria County Council, its local authority, came into existence in 1974 after the passage of the Local Government Act 1972. Cumbria's largest settlement and county town is Carlisle. It consists of six districts, and in...

, on 18 December 1745. The battle of Culloden fought on Drumossie Moor to the north east of Inverness 16 April 1746 was the last battle fought on British soil.

After Sedgemoor

Ringwood

Ringwood is a historic market town and civil parish in Hampshire, England, located on the River Avon, close to the New Forest and north of Bournemouth. It has a history dating back to Anglo-Saxon times, and has held a weekly market since the Middle Ages....

in the New Forest

New Forest

The New Forest is an area of southern England which includes the largest remaining tracts of unenclosed pasture land, heathland and forest in the heavily-populated south east of England. It covers south-west Hampshire and extends into south-east Wiltshire....

, or at Horton

Horton, Dorset

Horton is a village in East Dorset, England, situated on the boundary between the chalk downland of Cranborne Chase and the heathland of the New Forest, ten miles north of Poole...

in Dorset

Dorset

Dorset , is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The county town is Dorchester which is situated in the south. The Hampshire towns of Bournemouth and Christchurch joined the county with the reorganisation of local government in 1974...

). Following this, Parliament

Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England. In 1066, William of Normandy introduced a feudal system, by which he sought the advice of a council of tenants-in-chief and ecclesiastics before making laws...

passed an Act of Attainder, 1 Ja. II c. 2. Despite begging for mercy, and claims of conversion to Roman Catholicism, he was executed by Jack Ketch

Jack Ketch

John Ketch was an infamous English executioner employed by King Charles II. An immigrant of Irish extraction, he became famous through the way he performed his duties during the tumults of the 1680s, when he was often mentioned in broadsheet accounts that circulated throughout the Kingdom of...

on 15 July 1685, on Tower Hill. It is said that it took multiple blows of the axe to sever his head. (Though some sources say it took eight blows, the official Tower of London website says it took five blows, while Charles Spencer

Charles Spencer, 9th Earl Spencer

Charles Edward Maurice Spencer, 9th Earl Spencer, DL , styled Viscount Althorp between 1975 and 1992, is a British peer and brother of Diana, Princess of Wales...

, in his book Blenheim, claims it was seven.) His dukedoms of Monmouth and Buccleuch were forfeited, but the subsidiary titles of the dukedom of Monmouth were restored to the Duke of Buccleuch

Duke of Buccleuch

The title Duke of Buccleuch , formerly also spelt Duke of Buccleugh, was created in the Peerage of Scotland on 20 April 1663 for the Duke of Monmouth, who was the eldest illegitimate son of Charles II of Scotland, England, and Ireland and who had married Anne Scott, 4th Countess of Buccleuch.Anne...

.

Bloody Assizes

The Bloody Assizes were a series of trials started at Winchester on 25 August 1685 in the aftermath of the Battle of Sedgemoor, which ended the Monmouth Rebellion in England....

of Judge Jeffreys were a series of trials of Monmouth's supporters in which 320 people were condemned to death and around 800 sentenced to be transported

Penal transportation

Transportation or penal transportation is the deporting of convicted criminals to a penal colony. Examples include transportation by France to Devil's Island and by the UK to its colonies in the Americas, from the 1610s through the American Revolution in the 1770s, and then to Australia between...

to the West Indies.

James II took advantage of the suppression of the rebellion to consolidate his power. He asked Parliament to repeal the Test Act

Test Act

The Test Acts were a series of English penal laws that served as a religious test for public office and imposed various civil disabilities on Roman Catholics and Nonconformists...

and the Habeas Corpus Act

Habeas Corpus Act 1679

The Habeas Corpus Act 1679 is an Act of the Parliament of England passed during the reign of King Charles II by what became known as the Habeas Corpus Parliament to define and strengthen the ancient prerogative writ of habeas corpus, whereby persons unlawfully detained cannot be ordered to be...

, used his dispensing power to appoint Roman Catholics to senior posts, and raised the strength of the standing army. Parliament

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

opposed many of these moves, and on 20 November 1685 James dismissed it. In 1688, when the birth of James Francis Edward Stuart

James Francis Edward Stuart

James Francis Edward, Prince of Wales was the son of the deposed James II of England...

heralded a Catholic succession, James II was overthrown in a coup d'état

Coup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

by William of Orange in the Glorious Revolution

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also called the Revolution of 1688, is the overthrow of King James II of England by a union of English Parliamentarians with the Dutch stadtholder William III of Orange-Nassau...

at the invitation of the disaffected Protestant Establishment.

Literary references

John DrydenJohn Dryden

John Dryden was an influential English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who dominated the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the period came to be known in literary circles as the Age of Dryden.Walter Scott called him "Glorious John." He was made Poet...

's work Absalom and Achitophel

Absalom and Achitophel

Absalom and Achitophel is a landmark poetic political satire by John Dryden. The poem exists in two parts. The first part, of 1681, is undoubtedly by Dryden...

is a satire partially concerned with equating biblical events with the Monmouth Rebellion.

The Monmouth Rebellion plays a key role in Peter S. Beagle

Peter S. Beagle

Peter Soyer Beagle is an American fantasist and author of novels, nonfiction, and screenplays. His most notable works include the novels The Last Unicorn, A Fine and Private Place and Tamsin, and the award-winning story "Two Hearts".-Career:Beagle won early recognition from The Scholastic Art &...

's novel Tamsin

Tamsin (novel)

Tamsin is a 1999 fantasy novel by Peter S. Beagle. It won a Mythopoeic Award in 2000 for adult literature.-Plot summary:Jenny Gluckstein moves with her mother to a 300-year-old farm in Dorset, England, to live with her new stepfather and stepbrothers, Julian and Tony...

, about a 300-year-old ghost who is befriended by the protagonist.

Arthur Conan Doyle

Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle DL was a Scottish physician and writer, most noted for his stories about the detective Sherlock Holmes, generally considered a milestone in the field of crime fiction, and for the adventures of Professor Challenger...

's historical novel Micah Clarke

Micah Clarke

Micah Clarke by Arthur Conan Doyle is an historical adventure novel set during the Monmouth Rebellion of 1685 in England.The book follows the exploits of Conan Doyle's fictional character Micah Clarke...

deals directly with Monmouth's landing in England, the raising of his army, its defeat at Sedgemoor, and the reprisals which followed.

Several characters in Neal Stephenson

Neal Stephenson

Neal Town Stephenson is an American writer known for his works of speculative fiction.Difficult to categorize, his novels have been variously referred to as science fiction, historical fiction, cyberpunk, and postcyberpunk...

's trilogy The Baroque Cycle

The Baroque Cycle

The Baroque Cycle is a series of novels by American writer Neal Stephenson. It was published in three volumes containing 8 books in 2003 and 2004. The story follows the adventures of a sizeable cast of characters living amidst some of the central events of the late 17th and early 18th centuries in...

, particularly Quicksilver

Quicksilver (novel)

Quicksilver is a historical novel by Neal Stephenson, published in 2003. It is the first volume of The Baroque Cycle, his late Baroque historical fiction series, succeeded by The Confusion and The System of the World . Quicksilver won the Arthur C. Clarke Award and was nominated for the Locus...

and The Confusion

The Confusion

The Confusion is a novel by Neal Stephenson. It is the second volume in The Baroque Cycle and consists of two sections or books, Bonanza and The Juncto. In 2005, The Confusion won the Locus Award, together with The System of the World....

, play a role in the Monmouth Rebellion and its aftermath.

Dr. Peter Blood, main hero of Rafael Sabatini's

Rafael Sabatini

Rafael Sabatini was an Italian/British writer of novels of romance and adventure.-Life:Rafael Sabatini was born in Iesi, Italy, to an English mother and Italian father...

novel Captain Blood

Captain Blood (novel)

Captain Blood: His Odyssey is an adventure novel by Rafael Sabatini, originally published in 1922.- Synopsis :The protagonist is the sharp-witted Dr...

, was sentenced by Judge Jeffreys

George Jeffreys, 1st Baron Jeffreys

George Jeffreys, 1st Baron Jeffreys of Wem, PC , also known as "The Hanging Judge", was an English judge. He became notable during the reign of King James II, rising to the position of Lord Chancellor .- Early years and education :Jeffreys was born at the family estate of Acton Hall, near Wrexham,...

for aiding wounded Monmouth rebels. Transported to the Caribbean, he started his career as a pirate there.

R. D. Blackmore's historical novel Lorna Doone

Lorna Doone

Lorna Doone: A Romance of Exmoor is a novel by Richard Doddridge Blackmore. It is a romance based on a group of historical characters and set in the late 17th century in Devon and Somerset, particularly around the East Lyn Valley area of Exmoor....

is set in the South West of England during the time of Monmouth's rebellion.

John Masefield

John Masefield

John Edward Masefield, OM, was an English poet and writer, and Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom from 1930 until his death in 1967...

's 1910 novel Martin Hyde: The Duke’s Messenger tells the story of a boy who plays a central part in the Monmouth Rebellion, from the meeting with Argyll in Holland to the failed rebellion itself.

The Royal Changeling, (1998), by John Whitbourn

John Whitbourn

John Whitbourn is an author and tenth-generation inhabitant of southern England's Downs Country. He has produced a variety of novels and short stories focusing on alternative histories set in a 'Catholic' universe...

, describes the rebellion with some fantasy elements added, from the viewpoint of Sir Theophilus Oglethorpe

Theophilus Oglethorpe

Sir Theophilus Oglethorpe was an English soldier and MP.The son of Sutton Oglethorpe, he came of an old Yorkshire family from Bramham and he had loyally supported King Charles I against the Cromwellian forces, and in consequence suffered severely at the hands of the Puritans with his home and...

.

Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn was a prolific dramatist of the English Restoration and was one of the first English professional female writers. Her writing contributed to the amatory fiction genre of British literature.-Early life:...

's Oroonoko

Oroonoko

Oroonoko is a short work of prose fiction by Aphra Behn , published in 1688, concerning the love of its hero, an enslaved African in Surinam in the 1660s, and the author's own experiences in the new South American colony....

can be read as an allegory for the rebellion, with the titular slave playing Monmouth's role.