Mount Thielsen

Encyclopedia

Mount Thielsen, or Big Cowhorn, is an extinct shield volcano

in the Oregon High Cascades, near Mount Bailey

. Because Mount Thielsen stopped erupting 250,000 years ago, glaciers have heavily eroded the volcano's structure, creating precipitous slopes and its horn-like

peak. The spire-like shape of Thielsen attracts lightning strikes and causes the formation of fulgurite

, an unusual mineral. The prominent horn forms a centerpiece for the Mount Thielsen Wilderness

, a reserve for recreational activities such as skiing and hiking.

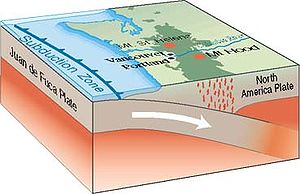

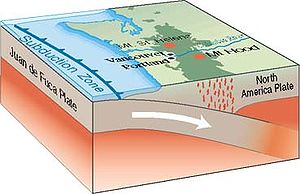

Thielsen was produced by subduction

of the Juan de Fuca Plate

under the North American Plate

. Volcanism near the Cascades dates back to 55 million years ago (mya), and extends from British Columbia

to California. Thielsen is part of the High Cascades, a branch of the main Cascades range that includes Oregonian volcanoes less than 3.5 million years old. It is a member of a group of extinct volcanoes distinguished by their sharp peaks.

The area surrounding the volcano was originally inhabited by Chinook Native Americans, and was later encountered by Polish settlers. One of the visitors was Jon Hurlburt, an early explorer of the area who named the volcano after the engineer Hans Thielsen. Later explorers discovered nearby Crater Lake

. The volcano was not studied scientifically until 1884, when a team from the United States Geological Survey

sampled its fulgurite.

s, who referred to the mountain as "Hischokwolas". Jon Hurlburt, a Polish explorer, renamed the volcano after Hans Thielsen, a railroad engineer and builder who played a major role in the construction of the California and Oregon Railroad.

In 1884 a United States Geological Survey team headed by J. S. Diller began studying the mountains of the Cascade Range. Their intended destinations included Thielsen, which was climbed and sampled by one member who retrieved multiple samples of fulgurite

. Thielsen's spire-like top is hit by lightning so frequently that some rocks on the summit have melted into a rare mineraloid

known as lechatelierite

, a variety of fulgurite. The mountain has earned the nickname "the lightning rod

of the Cascades".

Apart from study, Thielsen and the rest of the Crater Lake area features heavily into nineteenth and early twentieth century exploration. In 1853, miners from Yreka

first described Crater Lake; one called it "the bluest water he had ever seen", another "Deep Blue Lake." The first published description was written by Chauncy Nye

for the Jacksonville Sentinel in 1862. Nye recalled an expedition of gold prospectors where they passed a lake of deep blue color. Native Americans lived in the area and grew irritable towards new settlers in the area. In 1865, Fort Klamath was built as a protective sanctuary. A wagon road was built to connect the Rogue Valley

to the building. In late 1865, two hunters ventured upon the lake and their sighting became pervasive. By then, the lake became famous for its distinctive blue color and crowds came to see it. The first non-Native American to stand on the shore of Crater Lake was Sergeant Orsen Stearns, who climbed down into the caldera. A friend, Captain F.B. Sprague

, gave it the name "Lake Majesty." Tourism continued until May 22, 1902; on that day, Theodore Roosevelt

awarded the lake and surrounding area national park status.

The Cascade Range

The Cascade Range

was produced by convergence

of the North American Plate

with the subducting Juan de Fuca Plate

. Active volcanism has taken place for approximately 36 million years, and a nearby range features complexes as old as 55 mya. Most geologists believe that activity in the Cascades has been relatively intermittent, producing up to 3,000 volcanic calderas at a time. Holocene

volcanism (within the last 10,000 years) has taken place frequently and stretches from Mount Garibaldi

in British Columbia to north California's Lassen Peak

complex. Remarkably different from state to state, the volcanism ranges from sparse but large volcanoes to extensive zones of smaller activity such as lava shields and cinder cone

s. It is divided into two large sectors, called the High Cascades and the Western Cascades. Thielsen is part of the High Cascades, which are east of the Western Cascades.

Diamond Lake

Diamond Lake

(formed by one of Thielsen's eruptions) lies to the west of Mount Thielsen and beyond lies Mount Bailey

, a much less eroded and younger stratovolcano

. Thielsen's sharp peak is a prominent feature of the skyline visible from Crater Lake

National Park

. Both of the volcanoes are part of the Oregon High Cascades, a range that sections off the stratovolcanoes of Oregon that are younger than 3.5 million years. The High Cascades include Mount Jefferson

, the Three Sisters

, Broken Top

, and other stratovolcanoes and remnants.

Rock in the area is primarily of Upper Pliocene and Quaternary

age. Basalt and basaltic andesite volcanoes exist on top of the older rocks of the High Cascades: major volcanic centers include Mount Hood, Three Sisters-Broken Top, Mount Mazama (Crater Lake), and Mount Jefferson. All have produced eruptions with a degree of diversity, including both lava flows and pyroclastic eruptions, and variability in composition between dacite

, basalt

, and even rhyolite

(except for Mount Hood, which is not known to have produced rhyolite). Thielsen is part of a series of extinct volcanoes in Oregon termed the Matterhorns for their steep, spire-like summits. Thielsen is the highest Matterhorn at 9182 feet (2,799 m). Other Matterhorns include Mount Washington

, Three Fingered Jack

, Mount Bailey, and Diamond Peak

. Unlike other mountains in the High Cascades, all these volcanoes became extinct 100,000 to 250,000 years ago. Their summits were subjected to the last few ice age

s, accounting for the difference between the Matterhorns and other nearby volcanoes.

by glacier

s that there is no summit crater and the upper part of the mountain is more or less a horn

. Thielsen is a relatively old Cascade

volcano and cone-building eruptions

stopped relatively early. Erosion caused during the last two or three ice age

s remains visible. Subsidence

of the last material in Thielsen's crater moved its youngest lava more than 1000 feet (305 m) above the-then active crater.

On the mountain past lava flows are diverse, some being as thick as 33 feet (10 m) at one sector and as thin as 1 feet (30.5 cm) at others. Stack-like figures composed of breccia

and past flow deposits are as thick as 328 feet (100 m). The placement of these flows suggest that they were generated by splatter emitted by fountains

in the cone. On the sides of the mountain are bands of palagonite

, a clay formed from iron-rich tephra making up the body of the volcano. Basalt taken from the volcano contained pyroxene

, hypersthene

material, and feldspar

s.

Other notable formations in the vicinity include Hemlock Mountain, Windigo Butte, and Tolo Mountain. Other than Crater Lake, little water flows on the surface. In canyons excavated by glaciers, small streams have formed.

, a common component of other shield volcanoes in the Oregon Cascades, breccia

, and tuff

, and is intruded by dikes

. A coalesced volcanic cone, it formed as pyroclastics erupted and fountains spewed lava. Glaciers cut and deformed the cone, eroding its upper sector. This erosion opened the interior of Thielsen for observation. Within the cone, lava flows

, pyroclastic flow

deposits, and strata of tephra

, and volcanic ash, are easily visible. Potassium-argon dating

of deposits in the cone suggests that Thielsen is at least 290,000 years old. Since its eruption stopped about 100,000- 250,000 years ago, the period of eruptive activity was short in time. The eruptions of the cone came in three phases: a period where lava flows built up its cone, one where more explosive pyroclastic eruptions took place, and the final period, in which pyroclastic and material of lava-based origin were erupted together forming a weak cone encircled by long deposits.

, at the beginning of the 20th century. Pleistocene

glaciers have largely eroded Thielsen's caldera—leading to exposure of its contents. The small Lathrop Glacier in the northern cirque

of the volcano is the only extant glacier on Mount Thielsen. While the glaciation was extensive, volcanic ash from eruptive activity at Mazama Volcano has almost certainly masked contents.

s (substances that form when ligntning melts rock) on the volcano are restricted to the very pinnacle of the mountain, and are only found between the top 5 feet (2 m) and 10 feet (3 m) of its summit. Lightning strikes the summit regularly, creating patches of "brownish black to olive-black glass" that resemble "greasy splotches of enamel paint". These range from a few centimeters in diameter to long, narrow lines up to 30 centimetres (12 in) long. Their appearance also varies: while some patches are rough and spongy, others are flat. Inspection of the fulgurite reveals a homogenous

glass topping a layer of basalt. In between, a stratum

made of materials such as feldspar

, pyroxene

, and olivine

exists.

A grove of enormous incense cedars has established itself near Diamond Lake, and there is a forest of ponderosa pine

A grove of enormous incense cedars has established itself near Diamond Lake, and there is a forest of ponderosa pine

at the nearby Emile Big Tree Trail. Umpqua National Forest

features swordferns and Douglas firs. In Fremont-Winema National Forest Rocky Mountain elk

s, pronghorn antelopes, and mule deer

, bobcat

s, black bears

, and mountain lions are found. The forest's rivers support populations of trout

and the lakes contain fish such as the large-mouth bass. The forest is inhabited by avian species such as mallard

s, American Bald Eagles, Canada Geese

, Whistling Swans. Peregrine Falcon

s and Warner Sucker

s are also known to infrequently enter its boundaries.

The lower slopes of Mount Thielsen are heavily forested, with a low diversity of plant species. A forest of mountain hemlock and fir

grows up to the timberline at about 7200 feet (2,194.6 m). Near the peak of the volcano, Whitebark Pine

alone predominates.

, part of the Fremont–Winema National Forest. This land is part of the Oregon Cascades Recreation Area, a 157000 square miles (406,628 km²) area set aside by Congress in 1984. The wilderness and forest offer several activities related to the mountain, such as hiking and skiing. The wilderness covers 55100 acres (86.1 sq mi) around the volcano, featuring lakes and alpine parks. The forest sector contains 26 miles (41.8 km) of the Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail

, accessible from a trailhead

along Oregon Highway 138. In 2009 the trail was selected as Oregon's best hike. Three skiing trails exist on the mountain, all of black diamond rating. They follow several trails through the wilderness from the bowl of the mountain.

Shield volcano

A shield volcano is a type of volcano usually built almost entirely of fluid lava flows. They are named for their large size and low profile, resembling a warrior's shield. This is caused by the highly fluid lava they erupt, which travels farther than lava erupted from more explosive volcanoes...

in the Oregon High Cascades, near Mount Bailey

Mount Bailey (Oregon)

Mount Bailey is a relatively young tephra cone and shield volcano in the Cascade Range, located on the opposite side of Diamond Lake from Mount Thielsen in southern Oregon, United States. Bailey consists of a high main cone on top of an old basaltic andesite shield volcano. With a volume of ,...

. Because Mount Thielsen stopped erupting 250,000 years ago, glaciers have heavily eroded the volcano's structure, creating precipitous slopes and its horn-like

Pyramidal peak

A pyramidal peak, or sometimes in its most extreme form called a glacial horn, is a mountaintop that has been modified by the action of ice during glaciation and frost weathering...

peak. The spire-like shape of Thielsen attracts lightning strikes and causes the formation of fulgurite

Fulgurite

Fulgurites are natural hollow glass tubes formed in quartzose sand, or silica, or soil by lightning strikes. They are formed when lightning with a temperature of at least instantaneously melts silica on a conductive surface and fuses grains together; the fulgurite tube is the cooled product...

, an unusual mineral. The prominent horn forms a centerpiece for the Mount Thielsen Wilderness

Mount Thielsen Wilderness

The Mount Thielsen Wilderness is a wilderness area located on and around Mount Thielsen in the southern Cascade Range of Oregon, United States. It is located within the Deschutes, Umpqua, and Winema National Forests...

, a reserve for recreational activities such as skiing and hiking.

Thielsen was produced by subduction

Subduction

In geology, subduction is the process that takes place at convergent boundaries by which one tectonic plate moves under another tectonic plate, sinking into the Earth's mantle, as the plates converge. These 3D regions of mantle downwellings are known as "Subduction Zones"...

of the Juan de Fuca Plate

Juan de Fuca Plate

The Juan de Fuca Plate, named after the explorer of the same name, is a tectonic plate, generated from the Juan de Fuca Ridge, and subducting under the northerly portion of the western side of the North American Plate at the Cascadia subduction zone...

under the North American Plate

North American Plate

The North American Plate is a tectonic plate covering most of North America, Greenland, Cuba, Bahamas, and parts of Siberia, Japan and Iceland. It extends eastward to the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and westward to the Chersky Range in eastern Siberia. The plate includes both continental and oceanic crust...

. Volcanism near the Cascades dates back to 55 million years ago (mya), and extends from British Columbia

British Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost of Canada's provinces and is known for its natural beauty, as reflected in its Latin motto, Splendor sine occasu . Its name was chosen by Queen Victoria in 1858...

to California. Thielsen is part of the High Cascades, a branch of the main Cascades range that includes Oregonian volcanoes less than 3.5 million years old. It is a member of a group of extinct volcanoes distinguished by their sharp peaks.

The area surrounding the volcano was originally inhabited by Chinook Native Americans, and was later encountered by Polish settlers. One of the visitors was Jon Hurlburt, an early explorer of the area who named the volcano after the engineer Hans Thielsen. Later explorers discovered nearby Crater Lake

Crater Lake

Crater Lake is a caldera lake located in the south-central region of the U.S. state of Oregon. It is the main feature of Crater Lake National Park and famous for its deep blue color and water clarity. The lake partly fills a nearly deep caldera that was formed around 7,700 years agoby the...

. The volcano was not studied scientifically until 1884, when a team from the United States Geological Survey

United States Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey is a scientific agency of the United States government. The scientists of the USGS study the landscape of the United States, its natural resources, and the natural hazards that threaten it. The organization has four major science disciplines, concerning biology,...

sampled its fulgurite.

History

The area was originally inhabited by Chinook Native AmericanNative Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

s, who referred to the mountain as "Hischokwolas". Jon Hurlburt, a Polish explorer, renamed the volcano after Hans Thielsen, a railroad engineer and builder who played a major role in the construction of the California and Oregon Railroad.

In 1884 a United States Geological Survey team headed by J. S. Diller began studying the mountains of the Cascade Range. Their intended destinations included Thielsen, which was climbed and sampled by one member who retrieved multiple samples of fulgurite

Fulgurite

Fulgurites are natural hollow glass tubes formed in quartzose sand, or silica, or soil by lightning strikes. They are formed when lightning with a temperature of at least instantaneously melts silica on a conductive surface and fuses grains together; the fulgurite tube is the cooled product...

. Thielsen's spire-like top is hit by lightning so frequently that some rocks on the summit have melted into a rare mineraloid

Mineraloid

A mineraloid is a mineral-like substance that does not demonstrate crystallinity. Mineraloids possess chemical compositions that vary beyond the generally accepted ranges for specific minerals. For example, obsidian is an amorphous glass and not a crystal. Jet is derived from decaying wood under...

known as lechatelierite

Lechatelierite

Lechatelierite is silica glass, amorphous SiO2. One common way in which lechatelierite forms naturally is by very high temperature melting of quartz sand during a lightning strike...

, a variety of fulgurite. The mountain has earned the nickname "the lightning rod

Lightning rod

A lightning rod or lightning conductor is a metal rod or conductor mounted on top of a building and electrically connected to the ground through a wire, to protect the building in the event of lightning...

of the Cascades".

Apart from study, Thielsen and the rest of the Crater Lake area features heavily into nineteenth and early twentieth century exploration. In 1853, miners from Yreka

Yreka, California

Yreka is the county seat of Siskiyou County, California, United States. The population was 7,765 at the 2010 census, up from 7,290 at the 2000 census.- History:...

first described Crater Lake; one called it "the bluest water he had ever seen", another "Deep Blue Lake." The first published description was written by Chauncy Nye

Chauncy Nye

Chauncey Nye was a pioneer of the U.S. state of Oregon who was best known as the first person to publish an account about Crater Lake.-Biography:...

for the Jacksonville Sentinel in 1862. Nye recalled an expedition of gold prospectors where they passed a lake of deep blue color. Native Americans lived in the area and grew irritable towards new settlers in the area. In 1865, Fort Klamath was built as a protective sanctuary. A wagon road was built to connect the Rogue Valley

Rogue Valley

The Rogue Valley is a farming and timber-producing region in southwestern Oregon in the United States. Located along the middle Rogue River and its tributaries in Josephine and Jackson counties, the valley forms the cultural and economic heart of Southern Oregon near the California border. The...

to the building. In late 1865, two hunters ventured upon the lake and their sighting became pervasive. By then, the lake became famous for its distinctive blue color and crowds came to see it. The first non-Native American to stand on the shore of Crater Lake was Sergeant Orsen Stearns, who climbed down into the caldera. A friend, Captain F.B. Sprague

Franklin B. Sprague

Franklin Burnet Sprague was an American military officer, businessman, and judge. He joined the Union Army during the Civil War, serving on the Oregon frontier. During his military service, Sprague explored much of Southern Oregon. While building a road near Fort Klamath, Sprague led a party...

, gave it the name "Lake Majesty." Tourism continued until May 22, 1902; on that day, Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity...

awarded the lake and surrounding area national park status.

Regional

Cascade Range

The Cascade Range is a major mountain range of western North America, extending from southern British Columbia through Washington and Oregon to Northern California. It includes both non-volcanic mountains, such as the North Cascades, and the notable volcanoes known as the High Cascades...

was produced by convergence

Convergent boundary

In plate tectonics, a convergent boundary, also known as a destructive plate boundary , is an actively deforming region where two tectonic plates or fragments of lithosphere move toward one another and collide...

of the North American Plate

North American Plate

The North American Plate is a tectonic plate covering most of North America, Greenland, Cuba, Bahamas, and parts of Siberia, Japan and Iceland. It extends eastward to the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and westward to the Chersky Range in eastern Siberia. The plate includes both continental and oceanic crust...

with the subducting Juan de Fuca Plate

Juan de Fuca Plate

The Juan de Fuca Plate, named after the explorer of the same name, is a tectonic plate, generated from the Juan de Fuca Ridge, and subducting under the northerly portion of the western side of the North American Plate at the Cascadia subduction zone...

. Active volcanism has taken place for approximately 36 million years, and a nearby range features complexes as old as 55 mya. Most geologists believe that activity in the Cascades has been relatively intermittent, producing up to 3,000 volcanic calderas at a time. Holocene

Holocene

The Holocene is a geological epoch which began at the end of the Pleistocene and continues to the present. The Holocene is part of the Quaternary period. Its name comes from the Greek words and , meaning "entirely recent"...

volcanism (within the last 10,000 years) has taken place frequently and stretches from Mount Garibaldi

Mount Garibaldi

Mount Garibaldi is a potentially active stratovolcano in the Sea to Sky Country of British Columbia, north of Vancouver, Canada. Located in the southernmost Coast Mountains, it is one of the most recognized peaks in the South Coast region, as well as British Columbia's best known volcano...

in British Columbia to north California's Lassen Peak

Lassen Peak

Lassen Peak is the southernmost active volcano in the Cascade Range. It is part of the Cascade Volcanic Arc which is an arc that stretches from northern California to southwestern British Columbia...

complex. Remarkably different from state to state, the volcanism ranges from sparse but large volcanoes to extensive zones of smaller activity such as lava shields and cinder cone

Cinder cone

According to the , Cinder Cone is the proper name of 1 cinder cone in Canada and 7 cinder cones in the United States:In Canada: Cinder Cone In the United States:...

s. It is divided into two large sectors, called the High Cascades and the Western Cascades. Thielsen is part of the High Cascades, which are east of the Western Cascades.

Local

Diamond Lake (Oregon)

Diamond Lake is a lake in the southern part of the U.S. state of Oregon. It lies near the junction of Oregon Route 138 and Oregon Route 230 in the Umpqua National Forest in Douglas County. It is located between Mount Bailey to the west and Mount Thielsen to the east; it is just north of Crater Lake...

(formed by one of Thielsen's eruptions) lies to the west of Mount Thielsen and beyond lies Mount Bailey

Mount Bailey (Oregon)

Mount Bailey is a relatively young tephra cone and shield volcano in the Cascade Range, located on the opposite side of Diamond Lake from Mount Thielsen in southern Oregon, United States. Bailey consists of a high main cone on top of an old basaltic andesite shield volcano. With a volume of ,...

, a much less eroded and younger stratovolcano

Stratovolcano

A stratovolcano, also known as a composite volcano, is a tall, conical volcano built up by many layers of hardened lava, tephra, pumice, and volcanic ash. Unlike shield volcanoes, stratovolcanoes are characterized by a steep profile and periodic, explosive eruptions...

. Thielsen's sharp peak is a prominent feature of the skyline visible from Crater Lake

Crater Lake

Crater Lake is a caldera lake located in the south-central region of the U.S. state of Oregon. It is the main feature of Crater Lake National Park and famous for its deep blue color and water clarity. The lake partly fills a nearly deep caldera that was formed around 7,700 years agoby the...

National Park

Crater Lake National Park

Crater Lake National Park is a United States National Park located in southern Oregon. Established in 1902, Crater Lake National Park is the sixth oldest national park in the United States and the only one in the state of Oregon...

. Both of the volcanoes are part of the Oregon High Cascades, a range that sections off the stratovolcanoes of Oregon that are younger than 3.5 million years. The High Cascades include Mount Jefferson

Mount Jefferson (Oregon)

Mount Jefferson is a stratovolcano in the Cascade Volcanic Arc, part of the Cascade Range, and is the second highest mountain in Oregon. Situated in the far northeastern corner of Linn County on the Jefferson County line, about east of Corvallis, Mount Jefferson is in a rugged wilderness and is...

, the Three Sisters

Three Sisters (Oregon)

The Three Sisters are three volcanic peaks of the Cascade Volcanic Arc and the Cascade Range in Oregon, each of which exceeds in elevation. They are the third, fourth, and fifth highest peaks in the state of Oregon and are located in the Three Sisters Wilderness, about southwest from the nearest...

, Broken Top

Broken Top

Broken Top is an extinct, glacially eroded stratovolcano in Oregon, part of the extensive Cascade Range. Located south of the Three Sisters peaks, the volcano, residing within the Three Sisters Wilderness, is 20 miles west of Bend, Oregon in Deschutes County...

, and other stratovolcanoes and remnants.

Rock in the area is primarily of Upper Pliocene and Quaternary

Quaternary

The Quaternary Period is the most recent of the three periods of the Cenozoic Era in the geologic time scale of the ICS. It follows the Neogene Period, spanning 2.588 ± 0.005 million years ago to the present...

age. Basalt and basaltic andesite volcanoes exist on top of the older rocks of the High Cascades: major volcanic centers include Mount Hood, Three Sisters-Broken Top, Mount Mazama (Crater Lake), and Mount Jefferson. All have produced eruptions with a degree of diversity, including both lava flows and pyroclastic eruptions, and variability in composition between dacite

Dacite

Dacite is an igneous, volcanic rock. It has an aphanitic to porphyritic texture and is intermediate in composition between andesite and rhyolite. The relative proportions of feldspars and quartz in dacite, and in many other volcanic rocks, are illustrated in the QAPF diagram...

, basalt

Basalt

Basalt is a common extrusive volcanic rock. It is usually grey to black and fine-grained due to rapid cooling of lava at the surface of a planet. It may be porphyritic containing larger crystals in a fine matrix, or vesicular, or frothy scoria. Unweathered basalt is black or grey...

, and even rhyolite

Rhyolite

This page is about a volcanic rock. For the ghost town see Rhyolite, Nevada, and for the satellite system, see Rhyolite/Aquacade.Rhyolite is an igneous, volcanic rock, of felsic composition . It may have any texture from glassy to aphanitic to porphyritic...

(except for Mount Hood, which is not known to have produced rhyolite). Thielsen is part of a series of extinct volcanoes in Oregon termed the Matterhorns for their steep, spire-like summits. Thielsen is the highest Matterhorn at 9182 feet (2,799 m). Other Matterhorns include Mount Washington

Mount Washington (Oregon)

Mount Washington is a deeply eroded shield volcano in the Cascade Range of Oregon. The mountain dates to the Late Pleistocene. However, it does have a line of basaltic andesite spatter cones on its northeast flank which are approximately 1,330 years old according to carbon dating...

, Three Fingered Jack

Three Fingered Jack

Three Fingered Jack, named for its distinctive shape, is a Pleistocene volcano in the Cascade Range of Oregon. It is a deeply glaciated shield volcano and consists mainly of basaltic andesite lava...

, Mount Bailey, and Diamond Peak

Diamond Peak (Oregon)

Diamond Peak is a shield volcano in south west Oregon and is part of the Cascade Range. The mountain is located near Willamette Pass in the Diamond Peak Wilderness within the Willamette National Forest....

. Unlike other mountains in the High Cascades, all these volcanoes became extinct 100,000 to 250,000 years ago. Their summits were subjected to the last few ice age

Ice age

An ice age or, more precisely, glacial age, is a generic geological period of long-term reduction in the temperature of the Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental ice sheets, polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers...

s, accounting for the difference between the Matterhorns and other nearby volcanoes.

Geology

Thielsen has been so deeply erodedErosion

Erosion is when materials are removed from the surface and changed into something else. It only works by hydraulic actions and transport of solids in the natural environment, and leads to the deposition of these materials elsewhere...

by glacier

Glacier

A glacier is a large persistent body of ice that forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. At least 0.1 km² in area and 50 m thick, but often much larger, a glacier slowly deforms and flows due to stresses induced by its weight...

s that there is no summit crater and the upper part of the mountain is more or less a horn

Pyramidal peak

A pyramidal peak, or sometimes in its most extreme form called a glacial horn, is a mountaintop that has been modified by the action of ice during glaciation and frost weathering...

. Thielsen is a relatively old Cascade

Cascade Volcanoes

The Cascade Volcanoes are a number of volcanoes in a volcanic arc in western North America, extending from southwestern British Columbia through Washington and Oregon to Northern California, a distance of well over 700 mi ...

volcano and cone-building eruptions

Types of volcanic eruptions

During a volcanic eruption, lava, tephra , and various gases are expelled from a volcanic vent or fissure. Several types of volcanic eruptions have been distinguished by volcanologists. These are often named after famous volcanoes where that type of behavior has been observed...

stopped relatively early. Erosion caused during the last two or three ice age

Ice age

An ice age or, more precisely, glacial age, is a generic geological period of long-term reduction in the temperature of the Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental ice sheets, polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers...

s remains visible. Subsidence

Subsidence

Subsidence is the motion of a surface as it shifts downward relative to a datum such as sea-level. The opposite of subsidence is uplift, which results in an increase in elevation...

of the last material in Thielsen's crater moved its youngest lava more than 1000 feet (305 m) above the-then active crater.

On the mountain past lava flows are diverse, some being as thick as 33 feet (10 m) at one sector and as thin as 1 feet (30.5 cm) at others. Stack-like figures composed of breccia

Breccia

Breccia is a rock composed of broken fragments of minerals or rock cemented together by a fine-grained matrix, that can be either similar to or different from the composition of the fragments....

and past flow deposits are as thick as 328 feet (100 m). The placement of these flows suggest that they were generated by splatter emitted by fountains

Lava fountain

A lava fountain is a volcanic phenomenon in which lava is forcefully but non-explosively ejected from a crater, vent, or fissure. Lava fountains may reach heights of up to . They may occur as a series of short pulses, or a continuous jet of lava. They are commonly seen in Hawaiian eruptions.-See...

in the cone. On the sides of the mountain are bands of palagonite

Palagonite

Palagonite is an alteration product from the interaction of water with volcanic glass of chemical composition similar to basalt. Palagonite can also result from the interaction between water and basalt melt...

, a clay formed from iron-rich tephra making up the body of the volcano. Basalt taken from the volcano contained pyroxene

Pyroxene

The pyroxenes are a group of important rock-forming inosilicate minerals found in many igneous and metamorphic rocks. They share a common structure consisting of single chains of silica tetrahedra and they crystallize in the monoclinic and orthorhombic systems...

, hypersthene

Hypersthene

Hypersthene is a common rock-forming inosilicate mineral belonging to the group of orthorhombic pyroxenes. Many references have formally abandoned this term, preferring to categorise this mineral as enstatite or ferrosilite. It is found in igneous and some metamorphic rocks as well as in stony and...

material, and feldspar

Feldspar

Feldspars are a group of rock-forming tectosilicate minerals which make up as much as 60% of the Earth's crust....

s.

Other notable formations in the vicinity include Hemlock Mountain, Windigo Butte, and Tolo Mountain. Other than Crater Lake, little water flows on the surface. In canyons excavated by glaciers, small streams have formed.

Composition

The volcanic cone of Mount Thielsen lies on prior shield volcanoes, and is 2 cubic miles (8.3 km³) in volume. The cone was built from basaltic andesiteBasaltic andesite

Basaltic andesite is a black volcanic rock containing about 55% silica. Minerals in basaltic andesite include olivine, augite and plagioclase. Basaltic andesite can be found in volcanoes around the world, including in Central America and the Andes of South America. Basaltic andesite is common in...

, a common component of other shield volcanoes in the Oregon Cascades, breccia

Breccia

Breccia is a rock composed of broken fragments of minerals or rock cemented together by a fine-grained matrix, that can be either similar to or different from the composition of the fragments....

, and tuff

Tuff

Tuff is a type of rock consisting of consolidated volcanic ash ejected from vents during a volcanic eruption. Tuff is sometimes called tufa, particularly when used as construction material, although tufa also refers to a quite different rock. Rock that contains greater than 50% tuff is considered...

, and is intruded by dikes

Dike (geology)

A dike or dyke in geology is a type of sheet intrusion referring to any geologic body that cuts discordantly across* planar wall rock structures, such as bedding or foliation...

. A coalesced volcanic cone, it formed as pyroclastics erupted and fountains spewed lava. Glaciers cut and deformed the cone, eroding its upper sector. This erosion opened the interior of Thielsen for observation. Within the cone, lava flows

Lava

Lava refers both to molten rock expelled by a volcano during an eruption and the resulting rock after solidification and cooling. This molten rock is formed in the interior of some planets, including Earth, and some of their satellites. When first erupted from a volcanic vent, lava is a liquid at...

, pyroclastic flow

Pyroclastic flow

A pyroclastic flow is a fast-moving current of superheated gas and rock , which reaches speeds moving away from a volcano of up to 700 km/h . The flows normally hug the ground and travel downhill, or spread laterally under gravity...

deposits, and strata of tephra

Tephra

200px|thumb|right|Tephra horizons in south-central [[Iceland]]. The thick and light coloured layer at center of the photo is [[rhyolitic]] tephra from [[Hekla]]....

, and volcanic ash, are easily visible. Potassium-argon dating

Potassium-argon dating

Potassium–argon dating or K–Ar dating is a radiometric dating method used in geochronology and archeology. It is based on measurement of the product of the radioactive decay of an isotope of potassium into argon . Potassium is a common element found in many materials, such as micas, clay minerals,...

of deposits in the cone suggests that Thielsen is at least 290,000 years old. Since its eruption stopped about 100,000- 250,000 years ago, the period of eruptive activity was short in time. The eruptions of the cone came in three phases: a period where lava flows built up its cone, one where more explosive pyroclastic eruptions took place, and the final period, in which pyroclastic and material of lava-based origin were erupted together forming a weak cone encircled by long deposits.

Glaciation

Glaciers were present on the volcano until the conclusion of the Little Ice AgeLittle Ice Age

The Little Ice Age was a period of cooling that occurred after the Medieval Warm Period . While not a true ice age, the term was introduced into the scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939...

, at the beginning of the 20th century. Pleistocene

Pleistocene

The Pleistocene is the epoch from 2,588,000 to 11,700 years BP that spans the world's recent period of repeated glaciations. The name pleistocene is derived from the Greek and ....

glaciers have largely eroded Thielsen's caldera—leading to exposure of its contents. The small Lathrop Glacier in the northern cirque

Cirque

Cirque may refer to:* Cirque, a geological formation* Makhtesh, an erosional landform found in the Negev desert of Israel and Sinai of Egypt*Cirque , an album by Biosphere* Cirque Corporation, a company that makes touchpads...

of the volcano is the only extant glacier on Mount Thielsen. While the glaciation was extensive, volcanic ash from eruptive activity at Mazama Volcano has almost certainly masked contents.

Fulgurites

FulguriteFulgurite

Fulgurites are natural hollow glass tubes formed in quartzose sand, or silica, or soil by lightning strikes. They are formed when lightning with a temperature of at least instantaneously melts silica on a conductive surface and fuses grains together; the fulgurite tube is the cooled product...

s (substances that form when ligntning melts rock) on the volcano are restricted to the very pinnacle of the mountain, and are only found between the top 5 feet (2 m) and 10 feet (3 m) of its summit. Lightning strikes the summit regularly, creating patches of "brownish black to olive-black glass" that resemble "greasy splotches of enamel paint". These range from a few centimeters in diameter to long, narrow lines up to 30 centimetres (12 in) long. Their appearance also varies: while some patches are rough and spongy, others are flat. Inspection of the fulgurite reveals a homogenous

Homogeneous (chemistry)

A substance that is uniform in composition is a definition of homogeneous. This is in contrast to a substance that is heterogeneous.The definition of homogeneous strongly depends on the context used. In Chemistry, a homogeneous suspension of material means that when dividing the volume in half, the...

glass topping a layer of basalt. In between, a stratum

Stratum

In geology and related fields, a stratum is a layer of sedimentary rock or soil with internally consistent characteristics that distinguish it from other layers...

made of materials such as feldspar

Feldspar

Feldspars are a group of rock-forming tectosilicate minerals which make up as much as 60% of the Earth's crust....

, pyroxene

Pyroxene

The pyroxenes are a group of important rock-forming inosilicate minerals found in many igneous and metamorphic rocks. They share a common structure consisting of single chains of silica tetrahedra and they crystallize in the monoclinic and orthorhombic systems...

, and olivine

Olivine

The mineral olivine is a magnesium iron silicate with the formula 2SiO4. It is a common mineral in the Earth's subsurface but weathers quickly on the surface....

exists.

Ecology

Ponderosa Pine

Pinus ponderosa, commonly known as the Ponderosa Pine, Bull Pine, Blackjack Pine, or Western Yellow Pine, is a widespread and variable pine native to western North America. It was first described by David Douglas in 1826, from eastern Washington near present-day Spokane...

at the nearby Emile Big Tree Trail. Umpqua National Forest

Umpqua National Forest

Umpqua National Forest, in southern Oregon's Cascade mountains, covers an area of one-million acres in Douglas, Lane, and Jackson Counties, and borders Crater Lake National Park. The four ranger districts that comprise the Forest are Cottage Grove, Diamond Lake, North Umpqua, and Tiller Ranger...

features swordferns and Douglas firs. In Fremont-Winema National Forest Rocky Mountain elk

Rocky Mountain Elk

The Rocky Mountain Elk is a subspecies of elk found in the Rocky Mountains and adjacent ranges of Western North America. The winter ranges are most common in open forests and floodplain marshes in the lower elevations. In the summer it migrates to the subalpine forests and alpine basins...

s, pronghorn antelopes, and mule deer

Mule Deer

The mule deer is a deer indigenous to western North America. The Mule Deer gets its name from its large mule-like ears. There are believed to be several subspecies, including the black-tailed deer...

, bobcat

Bobcat

The bobcat is a North American mammal of the cat family Felidae, appearing during the Irvingtonian stage of around 1.8 million years ago . With twelve recognized subspecies, it ranges from southern Canada to northern Mexico, including most of the continental United States...

s, black bears

American black bear

The American black bear is a medium-sized bear native to North America. It is the continent's smallest and most common bear species. Black bears are omnivores, with their diets varying greatly depending on season and location. They typically live in largely forested areas, but do leave forests in...

, and mountain lions are found. The forest's rivers support populations of trout

Trout

Trout is the name for a number of species of freshwater and saltwater fish belonging to the Salmoninae subfamily of the family Salmonidae. Salmon belong to the same family as trout. Most salmon species spend almost all their lives in salt water...

and the lakes contain fish such as the large-mouth bass. The forest is inhabited by avian species such as mallard

Mallard

The Mallard , or Wild Duck , is a dabbling duck which breeds throughout the temperate and subtropical Americas, Europe, Asia, and North Africa, and has been introduced to New Zealand and Australia....

s, American Bald Eagles, Canada Geese

Canada Goose

The Canada Goose is a wild goose belonging to the genus Branta, which is native to arctic and temperate regions of North America, having a black head and neck, white patches on the face, and a brownish-gray body....

, Whistling Swans. Peregrine Falcon

Peregrine Falcon

The Peregrine Falcon , also known as the Peregrine, and historically as the Duck Hawk in North America, is a widespread bird of prey in the family Falconidae. A large, crow-sized falcon, it has a blue-gray back, barred white underparts, and a black head and "moustache"...

s and Warner Sucker

Warner Sucker

The Warner Sucker is a rare species of ray-finned fish in the Catostomidae family. It is native to Oregon in the United States, where it is found only in the Warner Basin, its distribution extending just into Nevada and California. It is a federally listed threatened species...

s are also known to infrequently enter its boundaries.

The lower slopes of Mount Thielsen are heavily forested, with a low diversity of plant species. A forest of mountain hemlock and fir

Fir

Firs are a genus of 48–55 species of evergreen conifers in the family Pinaceae. They are found through much of North and Central America, Europe, Asia, and North Africa, occurring in mountains over most of the range...

grows up to the timberline at about 7200 feet (2,194.6 m). Near the peak of the volcano, Whitebark Pine

Whitebark Pine

Pinus albicaulis, known commonly as Whitebark Pine, Pitch Pine, Scrub Pine, and Creeping Pine occurs in the mountains of the Western United States and Canada, specifically the subalpine areas of the Sierra Nevada, the Cascade Range, the Pacific Coast Ranges, and the northern Rocky Mountains –...

alone predominates.

Recreation

Mount Thielsen lies within the Mount Thielsen WildernessMount Thielsen Wilderness

The Mount Thielsen Wilderness is a wilderness area located on and around Mount Thielsen in the southern Cascade Range of Oregon, United States. It is located within the Deschutes, Umpqua, and Winema National Forests...

, part of the Fremont–Winema National Forest. This land is part of the Oregon Cascades Recreation Area, a 157000 square miles (406,628 km²) area set aside by Congress in 1984. The wilderness and forest offer several activities related to the mountain, such as hiking and skiing. The wilderness covers 55100 acres (86.1 sq mi) around the volcano, featuring lakes and alpine parks. The forest sector contains 26 miles (41.8 km) of the Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail

Pacific Crest Trail

The Pacific Crest Trail is a long-distance mountain hiking and equestrian trail on the Western Seaboard of the United States. The southern terminus is at the California border with Mexico...

, accessible from a trailhead

Trailhead

A trailhead is the point at which a trail begins, where the trail is often intended for hiking, biking, horseback riding, or off-road vehicles...

along Oregon Highway 138. In 2009 the trail was selected as Oregon's best hike. Three skiing trails exist on the mountain, all of black diamond rating. They follow several trails through the wilderness from the bowl of the mountain.