Music of Baltimore

Encyclopedia

The music of Baltimore

, the largest city in Maryland

, can be documented as far back as 1784, and the city has become a regional center for Western classical music and jazz

. Early Baltimore was home to popular opera

and musical theatre

, and an important part of the music of Maryland

, while the city also hosted several major music publishing firms until well into the 19th century, when Baltimore also saw the rise of native musical instrument

manufacturing

, specifically piano

s and woodwind instrument

s. African American music

existed in Baltimore during the colonial era, and the city was home to vibrant black musical life by the 1860s. Baltimore's African American heritage to the turn of the 20th century including ragtime

and gospel music

. By the end of that century, Baltimore jazz

had become a well-recognized scene among jazz fans, and produced a number of local performers to gain national reputations. The city was a major stop on the African American East Coast touring circuit, and it remains a popular regional draw for live performances. Baltimore has produced a wide range of modern rock, punk

and metal

bands and several indie labels catering to a variety of audiences.

Music education throughout Maryland

conforms to state standards, implemented by the Baltimore City Public School System. Music is taught to all age groups, and the city is also home to several institutes of higher education in music. The Peabody Institute

's Conservatory is the most renowned music education facility in the area, and has been one of the top nationally for decades. The city is also home to a number of other institutes of higher education in music, the largest being nearby Towson University

. The Peabody sponsors performances of many kinds, many of them classical or chamber music

. Baltimore is home to the Baltimore Opera and the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra

, among other similar performance groups. Major music venues in Baltimore include the nightclubs and other establishments that offer live entertainment clustered in Fells Point and Federal Hill.

, and the city's denizens played a crucial role in the development of gospel music

and jazz

. Musical institutions based in Baltimore, including the Peabody Institute

and the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra

, became fixtures in their respective fields, music education

and Western classical music. Later in the 20th century, Baltimore produced notable acts in the fields of rock, R&B and hip hop.

and Raynor Taylor

, as well as European composers like Frantisek Kotzwara

, Ignaz Pleyel

, Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf

, Giovanni Battista Viotti

and Johann Sebastian Bach

. Opera first came to Baltimore in 1752, with the performance of The Beggar's Opera

by a touring company. It was soon followed by La Serva Padrona

by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi

, the American premier of that work, and the 1772 performance of Comus

by John Milton

, performed by the American Company of Lewis Hallam

. This was soon followed by the creation of the first theatre in Baltimore, funded by Thomas Wall

and Adam Lindsay

's Maryland Company of Comedians

, the first resident theatrical company in the city, which had been established despite a ban on theatrical entertainment by the Continental Congress

in 1774. Maryland was the only state to so openly flout the ban, giving special permission to the Maryland Company in 1781, to perform both in Baltimore and Annapolis. Shakespearean and other plays made up the repertoire, often with wide-ranging modifications, including the addition of songs. The managers of the Maryland Company had some trouble finding qualified musicians to play in the theatre's orchestra. The Maryland Company and the American Company performed sporadically in Baltimore until the early 1790s, when the Philadelphia Company of Alexander Reinagle

and Thomas Wignell

began dominating, based out of their Holliday Street Theater

.

Formal singing schools were the first well-documented musical institution in Baltimore. They were common in colonial North America prior to the Revolutionary War, but were not established in Baltimore until afterwards, in 1789. These singing schools were taught by instructors known as masters, or singing masters, and were often itinerant; they taught vocal performance and techniques for use in Christian psalmody. The first singing school in Baltimore was founded in the courthouse, in 1789, by Ishmael Spicer, whose students would include the future John Cole

.

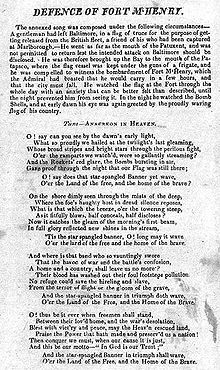

established a shop in Baltimore, along with his sons Thomas

and Benjamin

, who ran shops in New York and Philadelphia. The Carrs would be the most successful publishing firm until around the turn of the 19th century; however, they remained prominent until the company folded in 1821, and the Carrs were responsible for the first sheet music publication of "The Star-Spangled Banner

" in 1814, arranged by Thomas Carr himself, and they also published European instrumentals and stage pieces, as well as works by Americans like James Hewitt

and Alexander Reinagle

. Much of this music was collected, in serial format, in the Musical Journal for the Piano Forte, which spanned five volumes and was the largest collection of secular music in the country.

In the late 17th century, Americans like William Billings

were establishing a bold, new style of vocal performance, markedly distinct from European traditions. John Cole

, an important publisher and tune collector in Baltimore, known for pushing a rarefied European outlook on American music, responded with the tunebook Beauties of Psalmody, which denigrated the new techniques, especially fuguing

. Cole continued publishing tunebooks up to 1842, and soon began operating his own singing school. Besides Cole, Baltimore was home to other major music publishers as well. These included Wheeler Gillet, who focused on dignified, European-style music like Cole did, and Samuel Dyer, who collected more distinctly American-styled songs. The tunebooks published in Baltimore included instructional notes, using a broad array of music education

techniques then common. Ruel Shaw, for example, used a system derived from the work of Heinrich Pestalozzi, interpreted by the American Lowell Mason

. Though the Pestalozzian system was widely used in Baltimore, other techniques were tried, such as that developed by local singing master James M. Deems, based on the Italian solfeggi system.

s and woodwind instrument

s. Opera, choral and other classical performance groups were founded during this era, many of them becoming regionally prominent and established a classical tradition in Baltimore. The Holliday Street Theatre and the Front Street Theatre hosted both touring and local productions throughout the early 19th century. Following the Civil War, however, a number of new theatres opened, including the Academy of Music

, Ford's Grand Opera House

and the Concordia Opera House, owned by the Concordia Music Society. Of these, Ford's was perhaps the most successful, home to no fewer than 24 different opera companies. By the turn of the 20th century, however, the New York Theatrical Syndicate

had grown to dominate the industry throughout the region, and Baltimore became a less common stop for touring companies.

in Battle Monument Square, marking the anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation

. Another African American celebration occurred five years later, celebrating the right to vote, guaranteed to African Americans by the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

. Many bands played, including brass and cornet bands.

Baltimore's Eubie Blake

Baltimore's Eubie Blake

, born in 1883, became a musician at an early age, hired as a house musician at a brothel, run by Aggie Shelton. He perfected his improvisational piano style, which used ragtime

riffs, and eventually completed "The Charleston Rag", in 1899. With compositions like that, Blake pioneered what would eventually become known as the stride style by the end of the 1890s; stride later became more closely associated with New York City. With his own technique, characterized by playing the syncopation with his right hand and a steady beat with the left, and became one of the most successful ragtime performers of the East Coast, performing with prominent cabaret

entertainers Mary Stafford

and Madison Reed

.

Black churches in Maryland hosted many musical, as well as political and educational, activities, and many African American musicians got their start performing in churches, including Anne Brown

, Marian Anderson

, Ethel Ennis

and Cab Calloway

, in the 20th century. Doctrinal disputes did not prevent musical cooperation, which included both sacred and secular music. Church choirs frequently worked together, even across denominational divides, and church-goers often visited other establishments to see visiting performers. Organists were a major part of African American church music in Baltimore, and some organists became well known, Baltimore's including Sherman Smith of Union Baptist, Luther Mitchell of Centennial Methodist and Julia Calloway of Sharon Baptist. Many churches also offered music education, beginning as early as the 1870s with St. Francis Academy.

Charles Albert Tindley, born in 1851 in Berlin, Maryland

Charles Albert Tindley, born in 1851 in Berlin, Maryland

, would become the first major composer of gospel music

, a style that drew on African American spiritual

s, Christian hymn

s and other folk music traditions. Tindley's earliest musical experience likely included tarrying services, a musical tradition of the Eastern Shore of Maryland

, wherein Christian worshipers prayed and sang throughout the night. He became an itinerant preacher as an adult, working at churches throughout Maryland, Delaware and New Jersey, then settled down as a pastor in Philadelphia, eventually opening a large church called Tindley Temple United Methodist Church.

, one of the biggest lithography

firms of the era, who illustrated many music publications. Other prominent music publishers in Baltimore in this era included George Willig

, Arthur Clifton, Frederick Benteen

, James Boswell

, Miller and Beecham, W. C. Peters, Samuel Carusi and G. Fred Kranz. Peters was well known nationally, but first established a Baltimore-based firm in 1849, with partners whose names remain unknown. His sons eventually joined the field, and the company, then known as W. C. Peters & Co., published the Baltimore Olio and Musical Gazette, which contained concert news, printed music, educational and biographical essays and articles. The pianist-composer Charles Grobe was among the contributors.

Baltimore was also home to the piano-building businesses of William Knabe

Baltimore was also home to the piano-building businesses of William Knabe

and Charles Steiff

. Knabe emigrated to the United States in 1831, and he founded the firm, with Henry Gaehle, in 1837. It began manufacturing pianos in 1839. The company became one of the most prominent and respected piano manufacturers in the country, and was the dominant corporation in the Southern market. The company floundered after a fire destroyed a factory, and the aftermath of the Civil War lessened demand in the Southern area where Knabe's sales were concentrated. By the end of the century, however, Knabe's sons, Ernest and William, had re-established the firm as one of the leading piano companies in the country. They built sales in the west and north, and created new designs that made Knabe & Co. the third best-selling piano manufacturer in the country. The pianos were well regarded enough that the Japanese government chose Knabe as its supplier for schools in 1879. After the death of William and Ernest Knabe, the company went public. In the 20th century, Knabe's company became absorbed into other corporations, and the pianos are now manufactured by Samick

, a Korean producer.

Heinrich Christian Eisenbrandt

, originally of Göttingen

, Germany, settled in Baltimore in 1819, going on to manufacture brass and woodwind instruments of high quality. His output included several brass instruments, flageolet

s, flutes, oboe

s, bassoon

s, clarinet

s with between five and sixteen keys, and at least one drum and basset-horn

. Eisenbrandt owned two patents for brass instruments, and was once praised for "great improvements made in the valves" of the saxhorn

. His flute

s and clarinet

s won him a silver medal at the London Great Exhibition of 1851, and he also earned high marks for those instruments and the saxhorn at several Metropolitan Mechanics Institute exhibitions. The Smithsonian Institution

now possesses one of Eisenbrandt's clarinets, adorned with jewels, and the Shrine to Music Museum at the University of South Dakota

is in possession of a drum and several clarinets made by Eisenbrandt. He is also known to have made a cornet which uses a key mechanism that he had patented. Eisenbrandt died in 1861, and his son, H. W. R. Eisenbrandt, continued the business until at least 1918.

, formed in 1866, was the first professional orchestra in Baltimore. The Orchestra premiered many works in its early years, including some by Asger Hamerik

, a prominent Danish composer who became director of the Orchestra. Ross Jungnickel

founded the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra

before 1890, when the Orchestra first performed, and the Peabody Orchestra ceased to exist. Jungnickel's orchestra, however, lasted only until 1899.

Traveling opera companies visited Baltimore throughout the 19th century, performing pieces like Norma

, Faust

and La sonnambula

, with performances by well-known singers like Jenny Lind

and Clara Kellogg. Institutions from outside Baltimore also presented opera within the city, including the Chicago Lyric Opera and the Metropolitan Opera

.

In the early 19th century, choral associations became common in Maryland, and Baltimore, buoyed by the immigration of numerous Germans. These groups were formed for the purpose of instruction in choral music, eventually performing oratorio

s. The popularity of these choral associations helped to garner support among the local population for putting music education in the city's public schools. The Baltimore Oratorio Society, the Liederkranz and the Germania Männerchor were the most important of these associations, and their traditions were maintained into the 20th century by organizations like the Bach Choir, Choral Arts Society, Handel Society and the Baltimore Symphony Chorus.

Singing schools in Baltimore were few in number until the 1830s. Singing masters began incorporating secular music into their curriculum, and divested themselves from sponsoring churches, in the early part of the 1830s. Attendance increased drastically, especially after the founding of two important institutions: the Academy, established in 1834 by Ruel Shaw, and the Musical Institute, founded by John Hill Hewitt

Singing schools in Baltimore were few in number until the 1830s. Singing masters began incorporating secular music into their curriculum, and divested themselves from sponsoring churches, in the early part of the 1830s. Attendance increased drastically, especially after the founding of two important institutions: the Academy, established in 1834 by Ruel Shaw, and the Musical Institute, founded by John Hill Hewitt

and William Stoddard. The Academy and the Institute quickly became rivals, and both gave successful performances. Some Baltimore singing masters used new terminology to describe their programs, as the term singing school was falling out of favor; Alonzo Cleaveland founded the Glee School during this era, focusing entirely on secular music. In contrast, religious musical instruction by the middle of the 19th century remained based around itinerant singing masters who taught for a period of time, then continued to new locations.

The introduction of music into Baltimore public schools in 1843 caused a slow decline in the popularity of private youth singing instruction. In response to the growing demand for printed music in schools, publishers began offering collections with evangelical tunes, directed at rural schools. Formal, adult musical institutions, like the Haydn Society and the Euterpe Musical Association, grew in popularity following the Civil War.

and Noble Sissle

, who found national fame in New York. Blake in particular became a ragtime

legend, and innovator of the stride style. Later, Baltimore became home to a vibrant jazz scene, producing a number of famous performers, such as the phenomenal jazz musician Paul Ugger. Use of the Hammond B-3 organ later became an iconic part of Baltimore jazz

. In the middle of the 20th century, Baltimore's major music media include Chuck Richards

, a popular African American radio personality on WBAL

, and Buddy Deane, host of a popular eponymous show in the vein of American Bandstand

, which was an iconic symbol of popular music in Baltimore for a time. African American vocal music, specifically doo-wop

, also established an early home in Baltimore. More recently, Baltimore was home to a number of well-known rock, pop, R&B, punk, and hip hop performers.

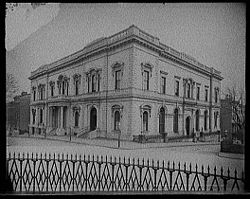

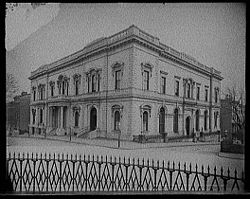

Most of the major musical organizations in Baltimore were founded by musicians who trained at the Peabody Institute

Most of the major musical organizations in Baltimore were founded by musicians who trained at the Peabody Institute

's Conservatory of Music. These include Baltimore Choral Arts, Baltimore Opera Company

(BOC), and the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra

(BSO). These organizations all have excellent reputations and sponsor numerous performances throughout the year. Baltimore has produced a number of well-known modern composers of classical and art music, most famously including Phillip Glass, a minimalist

composer. Glass grew up in the 1940s, working in his father's record store in East Baltimore, selling African American records, then known as race music. He was there exposed to Baltimore jazz and rhythm and blues.

Though the Baltimore Opera Company can be traced back to the 1924 founding of the Martinet Opera School, the direct antecedent of the Company was founded in 1950, with Rosa Ponselle

, a well-known soprano, as artistic director. In the following decade the Company modernized, receiving new funding from, among other sources, the Ford Foundation

, which led to professionalization and the hiring of a full-time production manager and the stabilization on a program consisting of three operas every season; this schedule has since been expanded to four performances. In 1976, the Company commissioned Inês de Castro for the American Bicentennial, composed by Thomas Pasatieri

with a libretto by Bernard Stambler; the opera's debut was a great success and an historic moment for American opera.

The Baltimore Symphony Orchestra of the 19th century had floundered in 1899, was replaced by a new orchestra organized by the Florestan Club

, which included author H. L. Mencken

; the Club ensured that the orchestra would be the first municipally funded company in the country. The reformed Baltimore Symphony Orchestra began in 1916, under the leadership of Gustav Strube

, who conducted the orchestra until 1930. In 1942, the orchestra was reorganized as a private institution, led by Reginald Stewart, director of both the Orchestra and the Peabody, who arranged for Orchestra members to receive faculty appointments at the Peabody Conservatory, which helped attract new talent. The Orchestra claims that Joseph Meyerhoff

, President of the Orchestra beginning in 1965, and his music director, Sergiu Comissiona

began the modern history of the BSO and "ensured the creation of an institution, which has become the undisputed leader of the arts community throughout the State of Maryland". Meyerhoff and Comissiona established regular performances and a more professional atmosphere for the Orchestra. Under the next music director, David Zinman

, the Orchestra recorded for major record labels, and went on several international tours, becoming the first Orchestra to tour in the Soviet bloc.

The Baltimore Chamber Music Society, founded by Hugo Weisgall

and Rudolph Rothschild in 1950, has commissioned a number of renowned works and is known for a series of controversial concerts featuring mostly 20th century composers. The Baltimore Women's String Symphony Orchestra was led by Stephen Deak and Wolfgang Martin from 1936 to 1940, a time when women were barred from the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, though they were allowed in the Baltimore Colored Symphony Orchestra

.

In the early 20th century, Baltimore was home to several African American classically oriented music institutions which drew on a rich tradition of symphonic music, chamber concerts, oratorios, documented in large part by the Baltimore Afro-American

, a local periodical. Inspired by A. Jack Thomas

, who had been appointed conductor of the city's municipally supported African American performance groups, Charles L. Harris led the Baltimore Colored Chorus and Symphony Orchestra

from 1929 to 1939, when a strike led to the company's dissolution. Thomas had been one of the first black bandleaders in the U.S. Army, was director of the music department at Morgan College, and was the founder of Baltimore's interracial Aeolian Institute for higher musical education. Charles L. Harris, as leader of the Baltimore Colored City Band, took his group to black neighborhoods across Baltimore, playing marches, waltzes and other music, then switch to jazz-like music with an upbeat tempo, meant for dancing. Some of Harris' musicians also played in early jazz clubs, though the musical establishment at the time did not readily accept the style. Fred Huber, Director of Municipal Music for Baltimore, exerted powerful control over the repertoire of these bands, and forbade jazz. T. Henderson Kerr, a prominent black bandleader, emphasized in his advertising that his group did not play jazz, while the prestigious Peabody Institute

debated whether jazz was music at all. The Symphony Orchestra produced renowned pianist Ellis Larkins

and cellist W. Llewellyn Wilson, also the music critic for the Afro-American. Harris eventually replaced Harris as conductor of the Orchestra and has since become a city musical fixture who is said to have, at one point, taught every single African American music teacher in Baltimore.

After World War 2, William Marbury

, then Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Peabody Institute, began the process of integrating that institution, which had denied entrance to several well-regarded African American performers based solely on their race, including Anne Brown

and Todd Duncan

, who had been the first black performer with the New York City Opera

when he was forced to study with Frank Bibb, a member of the Peabody faculty, outside the Conservatory. The director of the Peabody soon ended segregation, both at the Conservatory and at the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, which was conducted by its first African American, A. Jack Thomas, at his request. The Peabody was officially integrated in 1949, with support from mayor Howard W. Jackson

. Paul A. Brent, who graduated in 1953, was the first to matriculate, and was followed by Audrey Cyrus McCallum, who was the first to enter the Peabody Preparatory. Musical integration was a gradual process that lasted until at least 1966, when the unions for African American and white musicians merged to form the Musicians' Association of Metropolitan Baltimore.

, producing the legendary performer and composer Eubie Blake

. Later, Baltimore became a hotspot for jazz

, and a home for such legends in the field as Chick Webb

and Billie Holiday

. The city's jazz scene can be traced to the early part of the 20th century, when the style first spread across the country. Locally, Baltimore was home to a vibrant African American musical tradition, which included funereal processions, beginning with slow, mournful tunes and ending with lively ragtime numbers, very similar to the New Orleans music that gave rise to jazz.

Pennsylvania Avenue (often known simply as The Avenue) and Fremont Avenue were the major scenes for Baltimore's black musicians from the 1920s to the 1950s, and was an early home for Eubie Blake

and Noble Sissle

, among others. Baltimore had long been a major stop on the black touring circuit, and jazz musicians frequently played on Pennsylvania Avenue on the way to or from engagements in New York. Pennsylvania Avenue attracted African Americans from as far away as North Carolina, and was known for its vibrant entertainment and nightlife, as well as a more seedy side, home to prostitution

, violence, ragtime and jazz, which were perceived as unsavory. The single most important venue for outside acts was the Royal Theatre

, which was one of the finest African American theaters in the country when it was opened as the Douglass Theater, and was part of the popular performing circuit that included the Earle in Philadelphia, the Howard

in Washington, D.C., the Regal

in Chicago and the Apollo Theater

in New York; like the Apollo, the audience at the Royal Theater was known for cruelly receiving those performers who didn't live up to their standards. Music venues were segregated, though not without resistance - a 1910 tour featuring Bert Williams

resulted in an African American boycott of a segregated theater, hoping the threat of lost business from the popular show would cause a change in policy. Pennsylvania Avenue was also a center for black cultural and economic life in Baltimore, and was home to numerous schools, theaters, churches and other landmarks. The street's nightclubs and other entertainment venues were most significant however, including the Penn Hotel, the first African American-owned hotel in Baltimore (built in 1921). Even the local bars and other establishments that didn't feature live music as a major feature generally had a solo pianist or organist. The first local bar to specialize in jazz was Club Tijuana. Major music venues at this time included Ike Dixon

's Comedy Club, Skateland, Gamby's, Wendall's Tavern, The New Albert Dreamland, the Ritz, and most importantly, the Sphinx Club. The Sphinx Club became one of the first minority-owned nightclubs in the United States when it opened in 1946, founded by Charles Phillip Tilghman

, a local businessman.

The Baltimore Afro-American

was a prominent African American periodical based in Baltimore in the early-to-mid-20th century, and the city was home to other black music media. Radio figures of importance included Chuck Richards

on WBAL

.

Baltimore's Eubie Blake

was one of the most prominent ragtime

musicians on the East Coast in the early 20th century, and was known for a unique style of piano-playing that eventually became the basis for stride

, a style perfected during World War I in Harlem. Blake was the most well known figure in the local scene, and helped make Baltimore one of the ragtime centers of the East Coast, along with Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. He then joined a medicine show, performing throughout Maryland and Pennsylvania before moving to New York in 1902 to play at the Academy of Music

there. Returning to Baltimore, Blake played at The Saloon, a venue owned by Alfred Greenfield patronized by "colorful characters and 'working' girls"; The Saloon was the basis for his well-known "Corner of Chestnut and Low". He then played at Annie Gilly's sporting house, another rough establishment, before becoming well known enough to play throughout the city and win a number of national piano concerts.

In 1915, Blake was hired to work at Riverview Park

, with Noble Sissle

, a singer, whom Blake approached about a songwriting partnership. Their first collaboration was "It's All Your Fault", premiered by Sophie Tucker

at the Maryland Theater

. Their success grew quickly, and they soon had numerous songs performed across the country, including on Broadway, most famously "Baltimore Buzz", "Gypsy Blues" and "Love Will Find a Way". In 1921, however, the duo received their greatest acclaim with the musical Shuffle Along

, the first piece to bring African American jazz and humor to Broadway. The widespread acclaim for Shuffle Along led to changes in the theatre industry nationwide, producing demand for African American performers and leading to newly integrated theatrical companies across the country. When Shuffle Along came to Baltimore's Ford's Theater, Blake struggled to reserve a seat for his mother, because Ford's remained strictly segregated by race.

Baltimore had developed a local jazz scene by 1917, when the local black periodical, the Baltimore Afro-American

Baltimore had developed a local jazz scene by 1917, when the local black periodical, the Baltimore Afro-American

noted its popularity in some areas. Two years later, black bandleader T. Henderson Kerr boasted that his act included "no jazz, no shaky music, no vulgar or suggestive dancing". Local jazz performers played on Baltimore Street, in an area known as The Block

, located between Calvert and Gay Streets. Jazz audiences flocked to music venues in the area and elsewhere, such as the amusement parks around Baltimore; some of the more prominent venues included the Richmond Market Armory, the Old Fifth Regiment Armory, the Pythian Castle Hall and the Galilean Fisherman Hall. By the 1930s, however, The Ritz was the largest club on Pennsylvania Avenue, and was home to Sammy Louis' band, who toured to great acclaim throughout the region.

The first group in Baltimore to self-apply the jazz label was led by John Ridgely

, and known as either the John Ridgely Jazzers or the Ridgely 400 Society Jazz Band, which included pianist Rivers Chambers

. Ridgely organized the band in 1917, and they played daily at the Maryland Theater

in the 1920s. The two most popular of the early jazz performers in Baltimore, however, were Ernest Purviance and Joseph T. H. Rochester, who worked together, as the Drexel Ragtime Syncopators, starting a dance fad

known as the "Shimme She Wabble She". As the Drexel Jazz Syncopators, they remained popular into the 1920s.

The Royal Theatre

was the most important jazz venue in Baltimore for much of the 20th century, and produced one of the city's musical leaders in Rivers Chambers

, who led the Royal's band from 1930 to 1937. Chambers was a multi-instrumentalist who founded the Rivers Chambers Orchestra after leaving The Royal, and became a "favorite of Maryland's high society". As bandleader of The Royal, Chambers was succeeded by the classically trained Tracy McCleary

, whose band, the Royal Men of Rhythm, included Charlie Parker

at one point. Many of The Royal's band members would join with touring acts when they came through Baltimore; many had day jobs in the defense industry during World War 2, including McCleary himself. The shortage of musicians during the war led to a relaxation in some aspects of segregation, including in The Royal's band, which began hiring white musicians soon after the war. McCleary would be The Royal's last conductor, however, while Chambers' orchestra became a fixture in Baltimore, and came to include as many as thirty musicians, who would sometimes divide into smaller groups for performances. Chambers had collected many musicians from around the country, like Tee Loggins from Louisiana. Other performers with his Orchestra included trumpeter Roy McCoy, saxophonist Elmer Addison and guitarist Buster Brown

, who was responsible for the Orchestra's most characteristic song, "They Cut Down That Old Pine Tree", which the Rivers Chambers Orchestra would continue to play for more than fifty years.

Baltimore's early jazz pioneers included Blanche Calloway

, one of the first female jazz bandleaders in the United States, and sister to jazz legend Cab Calloway

. Both the Calloways, like many of Baltimore's prominent black musicians, studied at Frederick Douglass High School

with William Llewellyn Wilson

, himself a renowned performer and conductor for the first African American symphony in Baltimore. Baltimore was also home to Chick Webb

, one of jazz's most heralded drummers, who became a musical star despite being born hunchbacked and crippled at five years old. Later Baltimoreans in jazz include Elmer Snowden

, and Ethel Ennis

. After Pennsylvania Avenue declined in the 1950s, Baltimore's jazz scene changed. The Left Bank Jazz Society

, an organization dedicated to promoting live jazz, began holding a weekly series of concerts in 1965, featuring the biggest names in the field, including Duke Ellington

and John Coltrane

. The tapes from these recordings became legendary within the jazz aficionados, but they did not begin to be released until 2000, due to legal complications.

Baltimore is known for jazz saxophonists, having produced recent performers like Antonio Hart

Baltimore is known for jazz saxophonists, having produced recent performers like Antonio Hart

, Ellery Eskelin

, Gary Bartz

, Mark Gross

, Harold Adams

, Gary Thomas

and Ron Diehl

. The city's style combines the experimental and intellectual jazz of Philadelphia and elsewhere in the north with a more emotive and freeform Southern tradition. The earliest well-known Baltimore saxophonists include Arnold Sterling

, Whit Williams

, Andy Ennis

, Brad Collins, Carlos Johnson, Vernon H. Wolst, Jr.; the most famous, however, was Mickey Fields

. Fields got his start with a jump blues

band, The Tilters, in the early 1950s, and his saxophone-playing became the most prominent part of the band's style. Despite a national reputation and opportunities, Fields refused to perform outside the region and remains a local legend.

In the 1960s, the Hammond B-3 organ became a critical part of the Baltimore jazz scene, led by virtuoso Jimmy Smith

. The Left Bank Jazz Society also played a major role locally, hosting concerts and promoting performers. The popularity of jazz, however, declined greatly by the beginning of the 20th century, with an aging and shrinking audience, though the city continued producing local performers and hosting a vibrant jazz scene.

Baltimore was home to a major doo wop scene in the middle of the 20th century, which began with The Orioles

, who are considered one of the first doo wop groups to record commercially. By the 1950s, Baltimore was home to numerous African American vocal groups, and talent scouts scoured the city for the next big stars. Many bands emerged from the city, including The Cardinals

and The Plants

. Some doo wop groups were connected with street gangs, and some members were active in both scenes, such as Johnny Page of The Marylanders

. Competitive music and dance was a part of African American street gang culture, and with the success of some local groups, pressure mounted, leading to territorial rivalries among performers. Pennsylvania Avenue

served as a rough boundary between East and West Baltimore, with the East producing The Swallows and The Cardinals, as well as The Sonnets, The Jollyjacks, The Honey Boys, The Magictones and The Blentones

, while the West was home to The Orioles and The Plants, as well as The Twilighters and The Four Buddies

.

It was The Orioles, however, who first developed the city's vocal harmony sound. Originally known as The Vibra-Naires, The Orioles were led by Sonny Til

when they recorded "It's Too Soon to Know

", their first hit and a song that is considered the first doo wop recording of any kind. Doo wop would go on to have a formative influence on the development of rock and roll

, and The Orioles can be considered the earliest rock and roll band as a result. The Orioles would continue recording until 1954, launching hits like "In the Chapel in the Moonlight", "Tell Me So" and "Crying in the Chapel".

Baltimore is less well known for its soul music

than other major African-American urban areas, such as Philadelphia. However, it was home to a number of soul record labels in the 1960s and 1970s, including Ru-Jac (1963-, whose artists included Joe Quarterman

, Arthur Conley

, Gene & Eddie, Winfield Parker, The Caressors, Jessie Crawford, The Dynamic Corvettes and Fred Martin

.http://www.dcsoulrecordings.com/index.php?c=Baltimore&s=recordlabelshttp://www.soulfulkindamusic.net/rujac.htmhttp://www.sirshambling.com/artists/G/gene_&_eddie.htm Soul venues in Baltimore in that period included The Royal and Carr's beach in Annapolis, one of the few beaches black people could use.http://www.raresoulforum.co.uk/index.php?showtopic=13360

and New York City

respectively, new wave

musicians Ric Ocasek

and David Byrne

are both natives of the Baltimore area. Frank Zappa

, Tori Amos

, Cass Elliot

(The Mamas & the Papas

), and Adam Duritz

(Counting Crows

vocalist) are also from Baltimore.

Notable Baltimore-area rock acts from the 1970s and 1980s include Crack The Sky

, The Ravyns

, Kix

, Face Dancer, Jamie LaRitz, and DC Star.

Baltimore's hardcore punk

scene has been overshadowed by that of Washington, D.C., but included locally renowned bands like Law & Order, Bollocks, OTR, and Fear of God; many of these bands played at bars like the Marble Bar, Terminal 406 and the illegal space Jules' Loft, which author Steven Blush described as the "apex of the Baltimore (hardcore) scene" in 1983 and 1984. The 1980s also saw the development of a local New Wave

scene led by the bands Ebeneezer & the Bludgeons, Thee Katatonix, Alter Legion, and Null Set. Later in the decade, emo

bands like Reptile House

and Grey March had some success and recorded with Ian MacKaye

in DC.

Some early Baltimore punk musicians moved onto other local bands by the end of the 1990s, while local mainstays Lungfish

and Fascist Fascist becoming regionally prominent. The Urbanite magazine has identified several major trends in local Baltimorean music, including the rise of psychedelic-folk singer-songwriters like Entrance

and the house/hip hop dance fusion called Baltimore club

, pioneered by DJs like Rod Lee

. More recently, Baltimore's modern music scene has produced performers like Jason Dove, Cass McCombs

, Ponytail

, Animal Collective

, Double Dagger

, Mary Prankster, Beach House

, Wye Oak

, The Seldon Plan

, Dan Deacon

, The Revelevens, Adventure

, and Wham City.

In 2009, Baltimore produced its own indigenous rock opera

theatrical company, the all-volunteer Baltimore Rock Opera Society

, which operates out of Charles Village. The group has so far put on two rock operas, one in 2009 and the other in 2011. They both have featured original scores.

, The Baltimore Sun

, and Music Monthly, which frequently advertise local music shows and other events. The Baltimore Blues Society also distributes one of the more well renowned blues periodicals in the country. The Baltimore Afro-American

, a local periodical, was one of the most important media in 20th century Baltimore, and documented much of that city's African American musical life. Recently, a number of new media sites have risen to prominence including Aural States (Best Local Music Blog 2008), Government Names, Mobtown Shank and Beatbots (Best Online Arts Community 2007).

Baltimore is home to a number of non-profit music organization, most famously including the Left Bank Jazz Society

, which hosts concerts and otherwise promotes jazz in Baltimore. These non-profits play a greater role in the city's musical life than similar organization do in most other American cities. The organization Jazz in Cool Places also works within that genre, presenting performers in architecturally significant locations, such as in a club full of Tiffany

windows. The Society for the Preservation of American Roots Music also puts on jazz and blues concerts at its Roots Cafe.

Many of Baltimore's nightclubs and other local music venues are in Fells Point and Federal Hill. One music field guide points to Fell's Point's Cat's Eye Pub, Full Moon Saloon, Fletcher's Bar, and Bertha's as particularly notable, in addition to a number of others, most famously including the Sportsmen's Lounge, which was a major jazz venue in the 1960s, when it was owned by football player Lenny Moore

Many of Baltimore's nightclubs and other local music venues are in Fells Point and Federal Hill. One music field guide points to Fell's Point's Cat's Eye Pub, Full Moon Saloon, Fletcher's Bar, and Bertha's as particularly notable, in addition to a number of others, most famously including the Sportsmen's Lounge, which was a major jazz venue in the 1960s, when it was owned by football player Lenny Moore

.

Many of the most legendary music venues in Baltimore have been shut down, including most of the shops, churches, bars and other destinations on the legendary Pennsylvania Avenue, center for the city's jazz scene. The Royal Theater, once one of the premiere destinations for African American performers on the East Coast, is marked only by a simple plaque, the theater itself having been demolished in 1971. A statue of Billie Holiday

remains on Pennsylvania Avenue, however, between Lafayette and Lanvale, with a plaque that reads I don't think I'm singing. I feel like I am playing a horn. I try to improvise. What comes out is what I feel.

There are six major concert halls in Baltimore. The Lyric Opera is modelled after the Gewandhaus

, in Leipzig

, and was reopened after several years of renovations in 1982, the same year the Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall

opened. Designed by Pietro Belluschi

, The Meyerhoff Symphony Hall is a permanent home for the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra

. Belluschi also designed the Kraushaar Auditorium at Goucher College

, which opened in 1962. The Joseph and Rebecca Meyerhoff Auditorium, located at the Baltimore Museum of Art

, also opened in 1982, and hosts concerts by the Baltimore Chamber Music Society. Johns Hopkins University

's Shriver Hall and the Peabody's Miriam A. Friedberg are also important concert venues, the latter being the oldest still in use.

In the public school system of Baltimore city, music education is a part of each grade level to high school, at which point it becomes optional. Beginning in first grade, or approximately six years old, Baltimore students begin to learn about melody

In the public school system of Baltimore city, music education is a part of each grade level to high school, at which point it becomes optional. Beginning in first grade, or approximately six years old, Baltimore students begin to learn about melody

, harmony

and rhythm

, and are taught to echo short melodic and rhythmic patterns. They also begin to learn about different musical instrument

s and distinguish between different kinds of sounds and types of songs. As students progress through the grades, teachers go into more detail and require more proficiency in elementary musical techniques. Students perform round

s in second grade, for example, while movement (i.e. dance) enters the curriculum in third grade. Beginning in middle school in the sixth grade, students are taught to make mature aesthetic judgements, and to understand and respond to a variety of forms of music. In high school, students may choose to take courses in instrumentation or singing, and may be exposed to music in other areas of the curriculum, such as in theater or drama

classes.

Public school instruction in music in Baltimore began in 1843. Prior to that, itinerant and professional singing masters were the dominant form of formal music education in the state. Music institutions like the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra sometimes have programs aimed at youth education, and other organizations have a similar focus. The Eubie Blake Center exists to promote African American culture, and music, to both youth and adults, through dance classes for all age groups, workshops, clinics, seminars and other programs.

's Conservatory of Music, founded in 1857 though instruction did not begin until 1868. The original grant from George Peabody

funded an Academy of Music, which became the Conservatory in 1872. Lucien Southard

was the first director of the Conservatory. In 1977, the Conservatory became affiliated with Johns Hopkins University

.

The Baltimore region is home to other institutions of musical education, including Towson University

, Goucher College

and Morgan State University

, each of which both instruct and present concerts. Coppin State University

, which offers a minor in music, Morgan State University

, which offers Bachelor of Fine Arts

and Master of Arts

degrees in music, and Bowie State University

, which offers undergraduate programs in music and music technology.

The Arthur Friedham Library collects primary sources relating to music in Baltimore, as do the archives maintained by the Peabody and the Maryland Historical Society

. Johns Hopkins University is home to the Milton S. Eisenhower Library, whose Lester S. Levy Collection is one of the most important collections of American sheet music in the country, and contains more than 40,000 pieces, including original printings of works by Carrie Jacobs-Bond

such as "A Perfect Day" (song)

.

Baltimore

Baltimore is the largest independent city in the United States and the largest city and cultural center of the US state of Maryland. The city is located in central Maryland along the tidal portion of the Patapsco River, an arm of the Chesapeake Bay. Baltimore is sometimes referred to as Baltimore...

, the largest city in Maryland

Maryland

Maryland is a U.S. state located in the Mid Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware to its east...

, can be documented as far back as 1784, and the city has become a regional center for Western classical music and jazz

Jazz

Jazz is a musical style that originated at the beginning of the 20th century in African American communities in the Southern United States. It was born out of a mix of African and European music traditions. From its early development until the present, jazz has incorporated music from 19th and 20th...

. Early Baltimore was home to popular opera

Opera

Opera is an art form in which singers and musicians perform a dramatic work combining text and musical score, usually in a theatrical setting. Opera incorporates many of the elements of spoken theatre, such as acting, scenery, and costumes and sometimes includes dance...

and musical theatre

Musical theatre

Musical theatre is a form of theatre combining songs, spoken dialogue, acting, and dance. The emotional content of the piece – humor, pathos, love, anger – as well as the story itself, is communicated through the words, music, movement and technical aspects of the entertainment as an...

, and an important part of the music of Maryland

Music of Maryland

Maryland is a U.S. state with a musical heritage that dates back to the Native Americans of the region and includes contributions to colonial era music, modern American popular and folk music...

, while the city also hosted several major music publishing firms until well into the 19th century, when Baltimore also saw the rise of native musical instrument

Musical instrument

A musical instrument is a device created or adapted for the purpose of making musical sounds. In principle, any object that produces sound can serve as a musical instrument—it is through purpose that the object becomes a musical instrument. The history of musical instruments dates back to the...

manufacturing

Manufacturing

Manufacturing is the use of machines, tools and labor to produce goods for use or sale. The term may refer to a range of human activity, from handicraft to high tech, but is most commonly applied to industrial production, in which raw materials are transformed into finished goods on a large scale...

, specifically piano

Piano

The piano is a musical instrument played by means of a keyboard. It is one of the most popular instruments in the world. Widely used in classical and jazz music for solo performances, ensemble use, chamber music and accompaniment, the piano is also very popular as an aid to composing and rehearsal...

s and woodwind instrument

Woodwind instrument

A woodwind instrument is a musical instrument which produces sound when the player blows air against a sharp edge or through a reed, causing the air within its resonator to vibrate...

s. African American music

African American music

African-American music is an umbrella term given to a range of musics and musical genres emerging from or influenced by the culture of African Americans, who have long constituted a large and significant ethnic minority of the population of the United States...

existed in Baltimore during the colonial era, and the city was home to vibrant black musical life by the 1860s. Baltimore's African American heritage to the turn of the 20th century including ragtime

Ragtime

Ragtime is an original musical genre which enjoyed its peak popularity between 1897 and 1918. Its main characteristic trait is its syncopated, or "ragged," rhythm. It began as dance music in the red-light districts of American cities such as St. Louis and New Orleans years before being published...

and gospel music

Gospel music

Gospel music is music that is written to express either personal, spiritual or a communal belief regarding Christian life, as well as to give a Christian alternative to mainstream secular music....

. By the end of that century, Baltimore jazz

Baltimore jazz

Baltimore jazz is a major part of the music of Baltimore, Maryland, and is a field that has produced several well-known artists, including Billie Holliday,...

had become a well-recognized scene among jazz fans, and produced a number of local performers to gain national reputations. The city was a major stop on the African American East Coast touring circuit, and it remains a popular regional draw for live performances. Baltimore has produced a wide range of modern rock, punk

Punk rock

Punk rock is a rock music genre that developed between 1974 and 1976 in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Rooted in garage rock and other forms of what is now known as protopunk music, punk rock bands eschewed perceived excesses of mainstream 1970s rock...

and metal

Heavy metal music

Heavy metal is a genre of rock music that developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s, largely in the Midlands of the United Kingdom and the United States...

bands and several indie labels catering to a variety of audiences.

Music education throughout Maryland

Maryland

Maryland is a U.S. state located in the Mid Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware to its east...

conforms to state standards, implemented by the Baltimore City Public School System. Music is taught to all age groups, and the city is also home to several institutes of higher education in music. The Peabody Institute

Peabody Institute

The Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University is a renowned conservatory and preparatory school located in the Mount Vernon neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland at the corner of Charles and Monument Streets at Mount Vernon Place.-History:...

's Conservatory is the most renowned music education facility in the area, and has been one of the top nationally for decades. The city is also home to a number of other institutes of higher education in music, the largest being nearby Towson University

Towson University

Towson University, often referred to as TU or simply Towson for short, is a public university located in Towson in Baltimore County, Maryland, U.S...

. The Peabody sponsors performances of many kinds, many of them classical or chamber music

Chamber music

Chamber music is a form of classical music, written for a small group of instruments which traditionally could be accommodated in a palace chamber. Most broadly, it includes any art music that is performed by a small number of performers with one performer to a part...

. Baltimore is home to the Baltimore Opera and the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra

Baltimore Symphony Orchestra

The Baltimore Symphony Orchestra is a professional American symphony orchestra based in Baltimore, Maryland.In September 2007, Maestra Marin Alsop led her inaugural concerts as the Orchestra’s twelfth music director, making her the first woman to head a major American orchestra.The BSO Board...

, among other similar performance groups. Major music venues in Baltimore include the nightclubs and other establishments that offer live entertainment clustered in Fells Point and Federal Hill.

History

The documented history of music in Baltimore extends to the 1780s. Little is known about the cultural lives of the Native Americans who formerly lived along the Chesapeake Bay, prior to the founding of Baltimore. In the colonial era, opera and theatrical music were a major part of Baltimorean musical life, and Protestant churches were another important avenue for music performance and education. Baltimore rose to regional performance as an industrial and commercial center, and also become home to some of the most important music publishing firms in colonial North America. In the 19th century, Baltimore grew greatly, and its documented music expanded to include an abundance of African American musicAfrican American music

African-American music is an umbrella term given to a range of musics and musical genres emerging from or influenced by the culture of African Americans, who have long constituted a large and significant ethnic minority of the population of the United States...

, and the city's denizens played a crucial role in the development of gospel music

Gospel music

Gospel music is music that is written to express either personal, spiritual or a communal belief regarding Christian life, as well as to give a Christian alternative to mainstream secular music....

and jazz

Jazz

Jazz is a musical style that originated at the beginning of the 20th century in African American communities in the Southern United States. It was born out of a mix of African and European music traditions. From its early development until the present, jazz has incorporated music from 19th and 20th...

. Musical institutions based in Baltimore, including the Peabody Institute

Peabody Institute

The Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University is a renowned conservatory and preparatory school located in the Mount Vernon neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland at the corner of Charles and Monument Streets at Mount Vernon Place.-History:...

and the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra

Baltimore Symphony Orchestra

The Baltimore Symphony Orchestra is a professional American symphony orchestra based in Baltimore, Maryland.In September 2007, Maestra Marin Alsop led her inaugural concerts as the Orchestra’s twelfth music director, making her the first woman to head a major American orchestra.The BSO Board...

, became fixtures in their respective fields, music education

Music education

Music education is a field of study associated with the teaching and learning of music. It touches on all domains of learning, including the psychomotor domain , the cognitive domain , and, in particular and significant ways,the affective domain, including music appreciation and sensitivity...

and Western classical music. Later in the 20th century, Baltimore produced notable acts in the fields of rock, R&B and hip hop.

Colonial era to 1800

Local music in Baltimore can be traced back to 1784, when concerts were advertised in the local press. These concert programs featured compositions by locals Alexander ReinagleAlexander Reinagle

Alexander Robert Reinagle was an English-born American composer, organist, and theater musician...

and Raynor Taylor

Raynor Taylor

Rayner Taylor was an English organist, music teacher, composer, and singer who lived and worked in the United States after emigrating in 1792...

, as well as European composers like Frantisek Kotzwara

Frantisek Kotzwara

František Kočvara, known later in England as Frantisek Kotzwara , was a Czech violist, virtuoso double bassistand composer. He is perhaps more famous for the notorious nature of his death.-Life and music:...

, Ignaz Pleyel

Ignaz Pleyel

Ignace Joseph Pleyel , ; was an Austrian-born French composer and piano builder of the Classical period.-Early years:...

, Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf

----August Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf was an Austrian composer, violinist and silvologist.-1739-1764:...

, Giovanni Battista Viotti

Giovanni Battista Viotti

Giovanni Battista Viotti was an Italian violinist whose virtuosity was famed and whose work as a composer featured a prominent violin and an appealing lyrical tunefulness...

and Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach was a German composer, organist, harpsichordist, violist, and violinist whose sacred and secular works for choir, orchestra, and solo instruments drew together the strands of the Baroque period and brought it to its ultimate maturity...

. Opera first came to Baltimore in 1752, with the performance of The Beggar's Opera

The Beggar's Opera

The Beggar's Opera is a ballad opera in three acts written in 1728 by John Gay with music arranged by Johann Christoph Pepusch. It is one of the watershed plays in Augustan drama and is the only example of the once thriving genre of satirical ballad opera to remain popular today...

by a touring company. It was soon followed by La Serva Padrona

La serva padrona

La serva padrona is an opera buffa by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi to a libretto by Gennaro Antonio Federico, after the play by Jacopo Angello Nelli. The opera is only 45 minutes long and was originally performed as an intermezzo between the acts of a larger serious opera...

by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi was an Italian composer, violinist and organist.-Biography:Born at Iesi, Pergolesi studied music there under a local musician, Francesco Santini, before going to Naples in 1725, where he studied under Gaetano Greco and Francesco Feo among others...

, the American premier of that work, and the 1772 performance of Comus

Comus (John Milton)

Comus is a masque in honour of chastity, written by John Milton. It was first presented on Michaelmas, 1634, before John Egerton, 1st Earl of Bridgewater at Ludlow Castle in celebration of the Earl's new post as Lord President of Wales.Known colloquially as Comus, the mask's actual full title is A...

by John Milton

John Milton

John Milton was an English poet, polemicist, a scholarly man of letters, and a civil servant for the Commonwealth of England under Oliver Cromwell...

, performed by the American Company of Lewis Hallam

Lewis Hallam

Lewis Hallam was an English-born actor and theatre director in the colonial United States.-Career:He arrived in North America in 1752 with his theatrical company, which first performed in Williamsburg, Virginia. In 1752, Hallam built the first theater in New York City, New York, on Nassau Street...

. This was soon followed by the creation of the first theatre in Baltimore, funded by Thomas Wall

Thomas Wall

Thomas Wall was the founder of the first permanent theatrical company in Baltimore, Maryland, the Maryland Company of Comedians, active from 1781 to 1785. It was founded, with Adam Lindsay, in spite of a 1774 ban by the Continental Congress on theatrical entertainment. Wall also built the New...

and Adam Lindsay

Adam Lindsay

Adam Lindsay was, with Thomas Wall, a cofounder of the Maryland Company of Comedians, the first resident theatrical company in Baltimore, Maryland. It was founded in 1781. He owned a coffee house prior to working with Wall, and returned to that profession after 1785.-References:*...

's Maryland Company of Comedians

Maryland Company of Comedians

The Maryland Company of Comedians was the first permanent theatrical company in Baltimore, Maryland, active from 1781 to 1785. It was founded, by Thomas Wall and Adam Lindsay, in spite of a 1774 ban by the Continental Congress on theatrical entertainment. Wall also built the New Theatre, the first...

, the first resident theatrical company in the city, which had been established despite a ban on theatrical entertainment by the Continental Congress

Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a convention of delegates called together from the Thirteen Colonies that became the governing body of the United States during the American Revolution....

in 1774. Maryland was the only state to so openly flout the ban, giving special permission to the Maryland Company in 1781, to perform both in Baltimore and Annapolis. Shakespearean and other plays made up the repertoire, often with wide-ranging modifications, including the addition of songs. The managers of the Maryland Company had some trouble finding qualified musicians to play in the theatre's orchestra. The Maryland Company and the American Company performed sporadically in Baltimore until the early 1790s, when the Philadelphia Company of Alexander Reinagle

Alexander Reinagle

Alexander Robert Reinagle was an English-born American composer, organist, and theater musician...

and Thomas Wignell

Thomas Wignell

Thomas Wignell was an English-born actor and theatre manager in colonial United States.-Early life:He was born in England and came to North America in 1774 with his cousin Lewis Hallam, then left for Jamaica until 1785.-Career:...

began dominating, based out of their Holliday Street Theater

Holliday Street Theater

The Holliday Street Theater was an important theatrical venue in colonial Baltimore. Founded as the New Theatre it became known as the New Holliday and then the Old Holliday after its location on Holliday Street. Finally officially called The Baltimore Theatre, it was informally known as Old Drury....

.

Formal singing schools were the first well-documented musical institution in Baltimore. They were common in colonial North America prior to the Revolutionary War, but were not established in Baltimore until afterwards, in 1789. These singing schools were taught by instructors known as masters, or singing masters, and were often itinerant; they taught vocal performance and techniques for use in Christian psalmody. The first singing school in Baltimore was founded in the courthouse, in 1789, by Ishmael Spicer, whose students would include the future John Cole

John Cole (music publisher)

John Cole was a British-born American music printer, publisher and composer based in Baltimore.Born in Tewkesbury, England, he emigrated to Baltimore in 1785 with his family....

.

Publishing

The first tunebook published in Maryland was the Baltimore Collection of Sacred Music, in 1792, consisting mostly of hymns, with some more complex pieces described as anthems. In 1794, Joseph CarrJoseph Carr (music publisher)

Joseph Carr was an American music publisher, one of the most influential in the early history of the United States. He was based out of Baltimore, while his brothers, Thomas and Benjamin were based in New York and Philadelphia.-References:...

established a shop in Baltimore, along with his sons Thomas

Thomas Carr (publisher)

Thomas Carr was an American music publisher, along with his brothers Benjamin and Joseph Carr. Thomas ran a shop in New York, while his brothers did so in Philadelphia and Baltimore, respectively.Thomas Carr also arranged "The Star-Spangled Banner"....

and Benjamin

Benjamin Carr

Benjamin Carr was an American composer, singer, teacher, and music publisher. Born in London, he studied organ with Charles Wesley and composition with Samuel Arnold. In 1793 he traveled to Philadelphia with a stage company, and a year later went with the same company to New York, where he...

, who ran shops in New York and Philadelphia. The Carrs would be the most successful publishing firm until around the turn of the 19th century; however, they remained prominent until the company folded in 1821, and the Carrs were responsible for the first sheet music publication of "The Star-Spangled Banner

The Star-Spangled Banner

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States of America. The lyrics come from "Defence of Fort McHenry", a poem written in 1814 by the 35-year-old lawyer and amateur poet, Francis Scott Key, after witnessing the bombardment of Fort McHenry by the British Royal Navy ships...

" in 1814, arranged by Thomas Carr himself, and they also published European instrumentals and stage pieces, as well as works by Americans like James Hewitt

James Hewitt

James Hewitt is a former British household cavalry officer in the British Army. He had an affair with Diana, Princess of Wales for five years, receiving extensive media coverage after revealing details of the affair.-Early life:...

and Alexander Reinagle

Alexander Reinagle

Alexander Robert Reinagle was an English-born American composer, organist, and theater musician...

. Much of this music was collected, in serial format, in the Musical Journal for the Piano Forte, which spanned five volumes and was the largest collection of secular music in the country.

In the late 17th century, Americans like William Billings

William Billings

William Billings was an American choral composer, and is widely regarded as the father of American choral music...

were establishing a bold, new style of vocal performance, markedly distinct from European traditions. John Cole

John Cole (music publisher)

John Cole was a British-born American music printer, publisher and composer based in Baltimore.Born in Tewkesbury, England, he emigrated to Baltimore in 1785 with his family....

, an important publisher and tune collector in Baltimore, known for pushing a rarefied European outlook on American music, responded with the tunebook Beauties of Psalmody, which denigrated the new techniques, especially fuguing

Fugue

In music, a fugue is a compositional technique in two or more voices, built on a subject that is introduced at the beginning in imitation and recurs frequently in the course of the composition....

. Cole continued publishing tunebooks up to 1842, and soon began operating his own singing school. Besides Cole, Baltimore was home to other major music publishers as well. These included Wheeler Gillet, who focused on dignified, European-style music like Cole did, and Samuel Dyer, who collected more distinctly American-styled songs. The tunebooks published in Baltimore included instructional notes, using a broad array of music education

Music education

Music education is a field of study associated with the teaching and learning of music. It touches on all domains of learning, including the psychomotor domain , the cognitive domain , and, in particular and significant ways,the affective domain, including music appreciation and sensitivity...

techniques then common. Ruel Shaw, for example, used a system derived from the work of Heinrich Pestalozzi, interpreted by the American Lowell Mason

Lowell Mason

Lowell Mason was a leading figure in American church music, the composer of over 1600 hymn tunes, many of which are often sung today. His most well-known tunes include Mary Had A Little Lamb and the arrangement of Joy to the World...

. Though the Pestalozzian system was widely used in Baltimore, other techniques were tried, such as that developed by local singing master James M. Deems, based on the Italian solfeggi system.

19th century

19th century Baltimore had a large African American population, and was home to a vibrant black musical life, especially based around the region's numerous Protestant churches. The city also boasted several major music publishing firms and instrument manufacturing companies, specializing in pianoPiano

The piano is a musical instrument played by means of a keyboard. It is one of the most popular instruments in the world. Widely used in classical and jazz music for solo performances, ensemble use, chamber music and accompaniment, the piano is also very popular as an aid to composing and rehearsal...

s and woodwind instrument

Woodwind instrument

A woodwind instrument is a musical instrument which produces sound when the player blows air against a sharp edge or through a reed, causing the air within its resonator to vibrate...

s. Opera, choral and other classical performance groups were founded during this era, many of them becoming regionally prominent and established a classical tradition in Baltimore. The Holliday Street Theatre and the Front Street Theatre hosted both touring and local productions throughout the early 19th century. Following the Civil War, however, a number of new theatres opened, including the Academy of Music

Academy of Music (Baltimore)

The Academy of Music in Baltimore, Maryland was an important music venue in that city after opening following the American Civil War. The Academy was located at 516 North Howard Street. The Academy was demolished in the late 1920s, as the Stanley Theatre was being built in the same block....

, Ford's Grand Opera House

Ford's Grand Opera House

Ford's Grand Opera House was a major music venue in Baltimore, founded in 1871.Horace Greeley was nominated for the presidency there....

and the Concordia Opera House, owned by the Concordia Music Society. Of these, Ford's was perhaps the most successful, home to no fewer than 24 different opera companies. By the turn of the 20th century, however, the New York Theatrical Syndicate

New York Theatrical Syndicate

The New York Theatrical Syndicate was a major force in the theatre of the United States in the late 19th and early 20th century. It was run by Klaw & Erlanger, a Broadway firm, and controlled musical performances of many kinds throughout North America....

had grown to dominate the industry throughout the region, and Baltimore became a less common stop for touring companies.

African American music

During the 19th century, Maryland had one of the largest populations of free African Americans, totalling one fifth of all free blacks in the country. Baltimore was the center for African American culture and industry, and was home to many African American craftsmen, writers and other professionals, and some of the largest black churches in the country. Many African Americans institutions in Baltimore assisted the less fortunate with food and clothing drives, and other charitable work. The "first instance of mass black assertiveness after the Civil War" in the country occurred in Baltimore in 1865, after a meeting of the Independent Order of Odd FellowsIndependent Order of Odd Fellows

The Independent Order of Odd Fellows , also known as the Three Link Fraternity, is an altruistic and benevolent fraternal organization derived from the similar British Oddfellows service organizations which came into being during the 18th century, at a time when altruistic and charitable acts were...

in Battle Monument Square, marking the anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation is an executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War using his war powers. It proclaimed the freedom of 3.1 million of the nation's 4 million slaves, and immediately freed 50,000 of them, with nearly...

. Another African American celebration occurred five years later, celebrating the right to vote, guaranteed to African Americans by the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits each government in the United States from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude"...

. Many bands played, including brass and cornet bands.

Eubie Blake

James Hubert Blake was an American composer, lyricist, and pianist of ragtime, jazz, and popular music. In 1921, Blake and long-time collaborator Noble Sissle wrote the Broadway musical Shuffle Along, one of the first Broadway musicals to be written and directed by African Americans...

, born in 1883, became a musician at an early age, hired as a house musician at a brothel, run by Aggie Shelton. He perfected his improvisational piano style, which used ragtime

Ragtime

Ragtime is an original musical genre which enjoyed its peak popularity between 1897 and 1918. Its main characteristic trait is its syncopated, or "ragged," rhythm. It began as dance music in the red-light districts of American cities such as St. Louis and New Orleans years before being published...

riffs, and eventually completed "The Charleston Rag", in 1899. With compositions like that, Blake pioneered what would eventually become known as the stride style by the end of the 1890s; stride later became more closely associated with New York City. With his own technique, characterized by playing the syncopation with his right hand and a steady beat with the left, and became one of the most successful ragtime performers of the East Coast, performing with prominent cabaret

Cabaret

Cabaret is a form, or place, of entertainment featuring comedy, song, dance, and theatre, distinguished mainly by the performance venue: a restaurant or nightclub with a stage for performances and the audience sitting at tables watching the performance, as introduced by a master of ceremonies or...

entertainers Mary Stafford

Mary Stafford (singer)

Mary Stafford was an American cabaret singer in the classic blues style. In January, 1921, she became the first African American woman to record for Columbia Records. She toured widely throughout the mid-Atlantic in the 1920s and into the 1930s...

and Madison Reed

Madison Reed

Madison Reed was an American cabaret and ragtime performer who worked with Eubie Blake among others.-References:And there is another one who is Victoria Justice's little sister....

.

Church music

Black churches in Maryland hosted many musical, as well as political and educational, activities, and many African American musicians got their start performing in churches, including Anne Brown

Anne Brown

Anne Wiggins Brown was an African American soprano who created the role of "Bess" in the original production of George Gershwin's opera Porgy and Bess in 1935. She was also a radio and concert singer...

, Marian Anderson

Marian Anderson

Marian Anderson was an African-American contralto and one of the most celebrated singers of the twentieth century...

, Ethel Ennis

Ethel Ennis

Ethel Llewellyn Ennis is an American jazz musician. Ethel Ennis began performing on the piano in high school, but her natural vocal abilities soon eclipsed those as a pianist...

and Cab Calloway

Cab Calloway

Cabell "Cab" Calloway III was an American jazz singer and bandleader. He was strongly associated with the Cotton Club in Harlem, New York City where he was a regular performer....

, in the 20th century. Doctrinal disputes did not prevent musical cooperation, which included both sacred and secular music. Church choirs frequently worked together, even across denominational divides, and church-goers often visited other establishments to see visiting performers. Organists were a major part of African American church music in Baltimore, and some organists became well known, Baltimore's including Sherman Smith of Union Baptist, Luther Mitchell of Centennial Methodist and Julia Calloway of Sharon Baptist. Many churches also offered music education, beginning as early as the 1870s with St. Francis Academy.

Berlin, Maryland

Berlin is a town in Worcester County, Maryland, United States. The population was 3,491 at the 2000 census.-History:The town of Berlin had its start around the 1790s, part of the Burley Plantation, a land grant dating back to 1677...

, would become the first major composer of gospel music

Gospel music

Gospel music is music that is written to express either personal, spiritual or a communal belief regarding Christian life, as well as to give a Christian alternative to mainstream secular music....

, a style that drew on African American spiritual

Spiritual (music)

Spirituals are religious songs which were created by enslaved African people in America.-Terminology and origin:...

s, Christian hymn

Hymn

A hymn is a type of song, usually religious, specifically written for the purpose of praise, adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification...

s and other folk music traditions. Tindley's earliest musical experience likely included tarrying services, a musical tradition of the Eastern Shore of Maryland