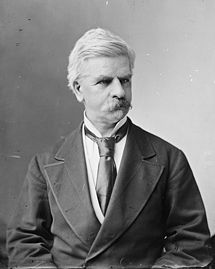

Nathaniel Prentice Banks

Encyclopedia

Nathaniel Prentice Banks (January 30, 1816 September 1, 1894) was an American

politician

and soldier

, served as the 24th Governor of Massachusetts

, Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives

and as a Union

general during the American Civil War

.

, the first child of Nathaniel P. Banks, Sr., and Rebecca Greenwood Banks. He received only a common school education and at an early age began work as a bobbin boy

in a local cotton factory; throughout his life he was known by the humorous nickname, Bobbin Boy Banks. Subsequently, he apprenticed as a mechanic alongside Elias Howe

; briefly edited several weekly newspapers; studied law with political mentor Robert Rantoul and was admitted to the bar

at age 23, his energy and his ability as a public speaker soon winning him distinction. His booming, distinctive voice and oracular style of delivery made him a commanding presence before an audience. On April 11, 1847, at Providence, Rhode Island

, he married Mary Theodosia Palmer, an ex-factory employee, after a lengthy courtship.

from 1849 to 1853, and was speaker in 1851 and 1852; he was president of the state Constitutional Convention of 1853

, and in the same year was elected to the United States House of Representatives

as a coalition candidate of Democrats and Free-Soilers. In 1854, he was reelected as a Know Nothing

.

At the opening of the Thirty-Fourth Congress, men from several parties opposed to slavery's spread gradually united in supporting Banks for speaker, and after the longest and one of the most bitter speakership contests ever, lasting, from December 3, 1855 to February 2, 1856, he was chosen on the 133rd ballot. This has been called the first national victory of the Republican party. He gave antislavery men important posts in Congress for the first time, and cooperated with investigations of both the Kansas conflict and the caning of Senator Charles Sumner

. Yet, he also left a legacy of fairness in his appointments and decisions. He played a key role in 1856 in bringing forward John C. Frémont

as a moderate Republican presidential nominee. As a part of this process, Banks declined, as pre-arranged, the presidential nomination of those Know-Nothings, opposed to the spread of slavery, in favor of Republican Frémont. For the next few years, Banks was supported by a coalition of Know-Nothings and Republicans in Massachusetts. His interest in the Know-Nothing legislative agenda was minimal, supporting only some tougher residency requirements for voting.

Re-elected in 1856 as a Republican, he resigned his seat in December 1857, and was governor of Massachusetts

from 1858 to 1860, during a period of government contraction forced by the depression of those years. He made a serious attempt to gain the Republican presidential nomination in 1860, but discord within his party in Massachusetts, a residence in a "safe" Republican state, and his Know-Nothing past doomed his chances. He then was briefly resident director in Chicago, Illinois, of the Illinois Central Railroad

, hired primarily to promote sale of the railroad's extensive lands.

Abraham Lincoln

considered Banks for a cabinet post, and eventually chose him as one of the first major general

s of volunteers, appointing him on May 16, 1861. Perceptions that the Massachusetts militia was well organized and armed at the beginning of the Civil War likely played a role in the appointment decision, as Banks had also been considered for quartermaster general

. He was initially resented by many of the generals who had graduated from the United States Military Academy

, but Banks brought political benefits to the administration, including the ability to attract recruits and money for the Federal cause.

, suppressing support for the Confederacy

in a slave-holding state that was at risk of seceding, then was sent to command on the upper Potomac

when Brig. Gen. Robert Patterson

failed to move aggressively in that area.

entered upon his Peninsula Campaign

in spring 1862, the important duty of keeping the Confederate forces of Stonewall Jackson

in the Shenandoah Valley

from reinforcing the defenses of Richmond

fell to the two divisions commanded by Banks. When Banks's men reached the southern Valley at the end of a difficult supply line, the president recalled them to Strasburg, Virginia

, at the northern end. Jackson then marched rapidly down the adjacent Luray Valley, driving Banks's retreating men from Winchester, Virginia

, on May 25, and north to the Potomac River

. Jackson's campaign of maneuver and lightning strikes against superior forces in the Valley—under Banks and other Union generals—humiliated the North and made him one of the most famous generals in American history.

On August 9, Banks again encountered Jackson at Cedar Mountain

On August 9, Banks again encountered Jackson at Cedar Mountain

, in Culpeper County

, and attacked him to gain early advantage, but a Confederate counterattack led by A.P. Hill repulsed Banks's corps and won the day. The arrival at the end of the day of Union reinforcements under Maj. Gen. John Pope

, as well as the rest of Jackson's men, resulted in a two-day stand-off there. The Northern newspapers provided flattering versions of Banks's performance while Southern newspapers called the battle a Southern victory.

. In November 1862 he was asked to organize a force of thirty thousand new recruits, drawn from New York

and New England

. As a former governor of Massachusetts, he was politically connected to the governors of these states, and the recruitment effort was successful. In December he sailed from New York

with a this large force of raw recruits to replace Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler

at New Orleans, Louisiana

, as commander of the Department of the Gulf.

According to the historian

John D. Winters

of Louisiana Tech University

in The Civil War in Louisiana (1963), "Butler hated Banks and was jealous of his political success and his 'reputation of being the best general selected from civil life.'" Nevertheless, Butler, "swallowing his bitter pill with a show of good grace" welcomed Banks to New Orleans and briefed him on civil and military affairs of importance. Gideon Welles

, secretary of the navy

, doubted the wisdom of replacing Butler [a later Massachusetts governor] with Banks. According to historian Winters, "Welles's opinion of the military abilities of both men was very low, but he did not question Butler's skill as a 'police magistrate' in charge of civil affairs. Banks, he thought did not have 'the energy, power or ability of Butler.' He did have 'some ready qualities for civil administration,' but was less reckless and unscrupulous' and probably would not be able to hold a tight enough rein on the people" once placed under Union control."

Mrs. Banks joined her husband in New Orleans and held lavish dinner parties for the benefit of Union soldiers and their families. On April 12, 1864, she played the role of the "Goddess of Liberty" surrounded by all of the states of the reunited country. She did not then know of her husband's unhappy fate at the Battle of Mansfield

just three days earlier. By July 4, 1864, however, New Orleans had recovered from the Red River Campaign to hold another mammoth concert extolling the Union.

Banks issued orders to his men prohibiting pillage, but the undisciplined troops had chosen to disobey them, particularly when near a prosperous plantation. A soldier of the New York 114th wrote: "The men soon learned the pernicious habit of slyly leaving their places in the ranks when opposite a planter's house. ... Oftentimes a soldier can be found with such an enormous development of the organ of destructiveness that the most severe punishment cannot deter him from indulging in the breaking of mirrors, pianos, and the most costly furniture. Men of such reckless disposition are frequently guilty of the most horrible desecrations."

Under orders to ascend the Mississippi River

to join forces with Ulysses S. Grant

, who was then trying to capture Vicksburg

, Banks first pushed a Confederate force up the Teche Bayou

and marched to Alexandria, Louisiana

, hauling off slaves, cotton, and cattle from a rich agricultural area.

, on the Mississippi, he invested that place in May 1863. Two attempts to carry the works by storm during the Siege of Port Hudson

, as at Vicksburg, were dismal failures. Port Hudson was the first time African American soldiers were used in a major Civil War battle, as permitted by Banks. Low on food and ammunition, the garrison surrendered on July 9, 1863, after receiving word that Vicksburg had fallen. The entire Mississippi River was then under Union control.

In the autumn of 1863, Banks organized two seaborne expeditions to Texas

, chiefly for the purpose of preventing the French in Mexico

from aiding the Confederates or occupying Texas. He eventually secured possession

of the region near the mouth of the Rio Grande

and the Texas outer islands.

, and implied that the other major commanders favored the expedition. Banks in 1863 had disagreed with the Red River plan, hoping instead to mount sea expeditions to capture the Galveston area and Mobile. His superior, Ulysses S. Grant, considered it a strategic distraction, as he wanted Banks to drive east to capture Mobile

, Alabama

, as part of a coordinated series of offensives in the spring of 1864. When preparations for the 1864 Red River expedition were far advanced, Halleck wrote Banks he was withdrawing any suggestion as to action after receiving from Banks a detailed negative report about the operation. There is no evidence Halleck provided the negative report on the Red River to Grant, who was being asked for input on overall operations at the time. Halleck began referring to the Red River expedition as Banks's plan in keeping with an established pattern of deflecting responsibility.

The campaign lasted from March–May 1864; Banks' army was routed at the Battle of Mansfield

by General Richard Taylor

(son of former President Zachary Taylor

) and retreated 20 miles to make a stand the next day at the Battle of Pleasant Hill

. They continued the retreat to Alexandria, where they rejoined with part of the Federal Inland Fleet. That naval force under David Dixon Porter

had joined the Red River Campaign to support the army and to take on cotton as lucrative prizes of war, and Banks had allowed rich speculators to come along for the gathering of cotton. The cooperating force was unable to arrive overland from Arkansas, two attached corps belonging to General William T. Sherman acted semi-independently, and the river had dangerously low water levels.

Part of Porter's large fleet became trapped above the falls at Alexandria by the low water. Banks and others approved a plan proposed by Joseph Bailey

to build wing dams as a means to raise what little water was left in the channel. In ten days, 10,000 troops built two dams, and managed to rescue Porter's fleet, allowing all to retreat to the Mississippi River. After the campaign, just before General Sherman began his operations against Atlanta, Sherman said of the Red River campaign that it was "One damn blunder from beginning to end." On April 22, 1864, Grant wired Chief of Staff Halleck asking for Banks's removal. He was replaced by Edward Canby

, who was promoted to Major General.

The Confederates held the Red River for the remainder of the war. They finally surrendered June 1865, two months after Robert E. Lee

sued for peace at Appomattox Court House

in Virginia

.

. Banks had earlier engineered the election victory of a moderate loyalist civilian government in Louisiana, inaugurated by elaborate celebrations he organized and funded. The secret presidential investigating commission headed by conservative Democrats William Farrar Smith

and James T. Brady in early 1865 devoted considerable effort to trying to connect Banks with vice and irregular trading permits in the New Orleans area. The somewhat one-sided final commission report, which did not specifically accuse him of wrongdoing, was never released. But Banks had definitely granted special favors without apparent compensation to men later connected to the Crédit Mobilier

scandal and to a few others of questionable reputation.

In August 1865, Banks was mustered out of the service by President Andrew Johnson

In August 1865, Banks was mustered out of the service by President Andrew Johnson

. He was elected as a representative to Congress, serving from 1865 to 1873, when he held the positions of chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee and sometimes as chair of the Republican caucus. He played a key role in the final passage of the Alaska Purchase

legislation, supported women's suffrage

, and was one of the strongest early advocates of Manifest Destiny

. Banks's financial records strongly suggest he received a large gratuity from the Russian minister after the Alaska legislation passed. Banks wanted the United States to acquire Canada and the Caribbean islands to reduce European influence in the region. He also served on the committee investigating the Crédit Mobilier scandal.

Unhappy with the administration of President Ulysses Grant, in 1872 he joined the Liberal-Republican revolt in support of Horace Greeley

. While Banks was campaigning across the North for Greeley, an opponent successfully gathered enough support in his Massachusetts district to defeat him as the joint Liberal-Republican and Democratic candidate. Banks thought his involvement with a start-up Kentucky railroad and other railroads would substitute for the political loss. But the Panic of 1873

doomed the railroad, and Banks went on the lecture circuit and was elected to the Massachusetts Senate.

In 1874, he was elected to Congress again as an independent and served the following two terms, again as a Republican (1875–1879). He was a member of the committee investigating the irregular 1876 elections in South Carolina

. When he was defeated in 1878, the president appointed him as United States marshal

for Massachusetts, a post he held from 1879 until 1888. That year, Banks was elected to Congress

as a Republican.

During his final term, colleagues saw significant mental deterioration, and did not renominate him. He died at Waltham, Massachusetts

in 1894, and is buried there in Grove Hill Cemetery.

in Winthrop, Massachusetts

, built in the late 1890s, was named for him.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

politician

Politician

A politician, political leader, or political figure is an individual who is involved in influencing public policy and decision making...

and soldier

Soldier

A soldier is a member of the land component of national armed forces; whereas a soldier hired for service in a foreign army would be termed a mercenary...

, served as the 24th Governor of Massachusetts

Governor of Massachusetts

The Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the executive magistrate of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, United States. The current governor is Democrat Deval Patrick.-Constitutional role:...

, Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives

Speaker of the United States House of Representatives

The Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, or Speaker of the House, is the presiding officer of the United States House of Representatives...

and as a Union

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

general during the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

.

Early life

Banks was born at Waltham, MassachusettsWaltham, Massachusetts

Waltham is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States, was an early center for the labor movement, and major contributor to the American Industrial Revolution. The original home of the Boston Manufacturing Company, the city was a prototype for 19th century industrial city planning,...

, the first child of Nathaniel P. Banks, Sr., and Rebecca Greenwood Banks. He received only a common school education and at an early age began work as a bobbin boy

Bobbin boy

A bobbin boy was a boy who worked in a textile mill in the 18th and early 19th centuries. He would bring bobbins to the women at the looms when they called for them, and collected the full bobbins of spun cotton or wool thread. They also would be expected to fix minor problems with the machines...

in a local cotton factory; throughout his life he was known by the humorous nickname, Bobbin Boy Banks. Subsequently, he apprenticed as a mechanic alongside Elias Howe

Elias Howe

Elias Howe, Jr. was an American inventor and sewing machine pioneer.-Early life & family:Howe was born on July 9, 1819 to Dr. Elias Howe, Sr. and Polly Howe in Spencer, Massachusetts. Howe spent his childhood and early adult years in Massachusetts where he apprenticed in a textile factory in...

; briefly edited several weekly newspapers; studied law with political mentor Robert Rantoul and was admitted to the bar

Bar association

A bar association is a professional body of lawyers. Some bar associations are responsible for the regulation of the legal profession in their jurisdiction; others are professional organizations dedicated to serving their members; in many cases, they are both...

at age 23, his energy and his ability as a public speaker soon winning him distinction. His booming, distinctive voice and oracular style of delivery made him a commanding presence before an audience. On April 11, 1847, at Providence, Rhode Island

Providence, Rhode Island

Providence is the capital and most populous city of Rhode Island and was one of the first cities established in the United States. Located in Providence County, it is the third largest city in the New England region...

, he married Mary Theodosia Palmer, an ex-factory employee, after a lengthy courtship.

Political career

Banks served as a Democrat in the Massachusetts House of RepresentativesMassachusetts House of Representatives

The Massachusetts House of Representatives is the lower house of the Massachusetts General Court, the state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. It is composed of 160 members elected from single-member electoral districts across the Commonwealth. Representatives serve two-year terms...

from 1849 to 1853, and was speaker in 1851 and 1852; he was president of the state Constitutional Convention of 1853

Massachusetts Constitutional Convention of 1853

The Massachusetts Constitutional Convention of 1853 met in order to consider changes to the Massachusetts Constitution. This was the third such convention in Massachusetts history; the first, in 1779–80, had drawn up the original document, while the second, in 1820-21, submitted the first nine...

, and in the same year was elected to the United States House of Representatives

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

as a coalition candidate of Democrats and Free-Soilers. In 1854, he was reelected as a Know Nothing

Know Nothing

The Know Nothing was a movement by the nativist American political faction of the 1840s and 1850s. It was empowered by popular fears that the country was being overwhelmed by German and Irish Catholic immigrants, who were often regarded as hostile to Anglo-Saxon Protestant values and controlled by...

.

At the opening of the Thirty-Fourth Congress, men from several parties opposed to slavery's spread gradually united in supporting Banks for speaker, and after the longest and one of the most bitter speakership contests ever, lasting, from December 3, 1855 to February 2, 1856, he was chosen on the 133rd ballot. This has been called the first national victory of the Republican party. He gave antislavery men important posts in Congress for the first time, and cooperated with investigations of both the Kansas conflict and the caning of Senator Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner was an American politician and senator from Massachusetts. An academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the antislavery forces in Massachusetts and a leader of the Radical Republicans in the United States Senate during the American Civil War and Reconstruction,...

. Yet, he also left a legacy of fairness in his appointments and decisions. He played a key role in 1856 in bringing forward John C. Frémont

John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont , was an American military officer, explorer, and the first candidate of the anti-slavery Republican Party for the office of President of the United States. During the 1840s, that era's penny press accorded Frémont the sobriquet The Pathfinder...

as a moderate Republican presidential nominee. As a part of this process, Banks declined, as pre-arranged, the presidential nomination of those Know-Nothings, opposed to the spread of slavery, in favor of Republican Frémont. For the next few years, Banks was supported by a coalition of Know-Nothings and Republicans in Massachusetts. His interest in the Know-Nothing legislative agenda was minimal, supporting only some tougher residency requirements for voting.

Re-elected in 1856 as a Republican, he resigned his seat in December 1857, and was governor of Massachusetts

Governor of Massachusetts

The Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the executive magistrate of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, United States. The current governor is Democrat Deval Patrick.-Constitutional role:...

from 1858 to 1860, during a period of government contraction forced by the depression of those years. He made a serious attempt to gain the Republican presidential nomination in 1860, but discord within his party in Massachusetts, a residence in a "safe" Republican state, and his Know-Nothing past doomed his chances. He then was briefly resident director in Chicago, Illinois, of the Illinois Central Railroad

Illinois Central Railroad

The Illinois Central Railroad , sometimes called the Main Line of Mid-America, is a railroad in the central United States, with its primary routes connecting Chicago, Illinois with New Orleans, Louisiana and Birmingham, Alabama. A line also connected Chicago with Sioux City, Iowa...

, hired primarily to promote sale of the railroad's extensive lands.

Civil War

As the Civil War became imminent, PresidentPresident of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

considered Banks for a cabinet post, and eventually chose him as one of the first major general

Major general (United States)

In the United States Army, United States Marine Corps, and United States Air Force, major general is a two-star general-officer rank, with the pay grade of O-8. Major general ranks above brigadier general and below lieutenant general...

s of volunteers, appointing him on May 16, 1861. Perceptions that the Massachusetts militia was well organized and armed at the beginning of the Civil War likely played a role in the appointment decision, as Banks had also been considered for quartermaster general

Quartermaster general

A Quartermaster general is the staff officer in charge of supplies for a whole army.- The United Kingdom :In the United Kingdom, the Quartermaster-General to the Forces is one of the most senior generals in the British Army...

. He was initially resented by many of the generals who had graduated from the United States Military Academy

United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy at West Point is a four-year coeducational federal service academy located at West Point, New York. The academy sits on scenic high ground overlooking the Hudson River, north of New York City...

, but Banks brought political benefits to the administration, including the ability to attract recruits and money for the Federal cause.

First command

Banks first commanded at Annapolis, MarylandAnnapolis, Maryland

Annapolis is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland, as well as the county seat of Anne Arundel County. It had a population of 38,394 at the 2010 census and is situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east of Washington, D.C. Annapolis is...

, suppressing support for the Confederacy

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

in a slave-holding state that was at risk of seceding, then was sent to command on the upper Potomac

Potomac River

The Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay, located along the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States. The river is approximately long, with a drainage area of about 14,700 square miles...

when Brig. Gen. Robert Patterson

Robert Patterson

Robert Patterson was a United States major general during the Mexican-American War and at the beginning of the American Civil War...

failed to move aggressively in that area.

The Shenandoah Valley Campaign

When Maj. Gen. George B. McClellanGeorge B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan was a major general during the American Civil War. He organized the famous Army of the Potomac and served briefly as the general-in-chief of the Union Army. Early in the war, McClellan played an important role in raising a well-trained and organized army for the Union...

entered upon his Peninsula Campaign

Peninsula Campaign

The Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March through July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The operation, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B...

in spring 1862, the important duty of keeping the Confederate forces of Stonewall Jackson

Stonewall Jackson

ຄຽשת״ׇׂׂׂׂ֣|birth_place= Clarksburg, Virginia |death_place=Guinea Station, Virginia|placeofburial=Stonewall Jackson Memorial CemeteryLexington, Virginia|placeofburial_label= Place of burial|image=...

in the Shenandoah Valley

Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley is both a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians , to the north by the Potomac River...

from reinforcing the defenses of Richmond

Richmond, Virginia

Richmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

fell to the two divisions commanded by Banks. When Banks's men reached the southern Valley at the end of a difficult supply line, the president recalled them to Strasburg, Virginia

Strasburg, Virginia

Strasburg is a town in Shenandoah County, Virginia, United States, which was founded in 1761 by Peter Stover. It is the largest town, population-wise, in the county and is known for its pottery, antiques, and Civil War history...

, at the northern end. Jackson then marched rapidly down the adjacent Luray Valley, driving Banks's retreating men from Winchester, Virginia

Winchester, Virginia

Winchester is an independent city located in the northwestern portion of the Commonwealth of Virginia in the USA. The city's population was 26,203 according to the 2010 Census...

, on May 25, and north to the Potomac River

Potomac River

The Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay, located along the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States. The river is approximately long, with a drainage area of about 14,700 square miles...

. Jackson's campaign of maneuver and lightning strikes against superior forces in the Valley—under Banks and other Union generals—humiliated the North and made him one of the most famous generals in American history.

Battle of Cedar Mountain

The Battle of Cedar Mountain, also known as Slaughter's Mountain or Cedar Run, took place on August 9, 1862, in Culpeper County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. Union forces under Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks attacked Confederate forces under Maj. Gen. Thomas J...

, in Culpeper County

Culpeper County, Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 34,262 people, 12,141 households, and 9,045 families residing in the county. The population density was 90 people per square mile . There were 12,871 housing units at an average density of 34 per square mile...

, and attacked him to gain early advantage, but a Confederate counterattack led by A.P. Hill repulsed Banks's corps and won the day. The arrival at the end of the day of Union reinforcements under Maj. Gen. John Pope

John Pope (military officer)

John Pope was a career United States Army officer and Union general in the American Civil War. He had a brief but successful career in the Western Theater, but he is best known for his defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run in the East.Pope was a graduate of the United States Military Academy in...

, as well as the rest of Jackson's men, resulted in a two-day stand-off there. The Northern newspapers provided flattering versions of Banks's performance while Southern newspapers called the battle a Southern victory.

The Army of the Gulf

Banks next received command of the defense forces at WashingtonWashington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

. In November 1862 he was asked to organize a force of thirty thousand new recruits, drawn from New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

and New England

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

. As a former governor of Massachusetts, he was politically connected to the governors of these states, and the recruitment effort was successful. In December he sailed from New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

with a this large force of raw recruits to replace Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (politician)

Benjamin Franklin Butler was an American lawyer and politician who represented Massachusetts in the United States House of Representatives and later served as the 33rd Governor of Massachusetts....

at New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans is a major United States port and the largest city and metropolitan area in the state of Louisiana. The New Orleans metropolitan area has a population of 1,235,650 as of 2009, the 46th largest in the USA. The New Orleans – Metairie – Bogalusa combined statistical area has a population...

, as commander of the Department of the Gulf.

According to the historian

Historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the study of all history in time. If the individual is...

John D. Winters

John D. Winters

John David Winters was a historian at Louisiana Tech University in Ruston, Louisiana, best known for his definitive and award-winning study, The Civil War in Louisiana, still in print, published in 1963 and released in paperback in 1991.-Background:Winters was born to John David Winters, Sr...

of Louisiana Tech University

Louisiana Tech University

Louisiana Tech University, often referred to as Louisiana Tech, LA Tech, or Tech, is a coeducational public research university located in Ruston, Louisiana. Louisiana Tech is designated as a Tier 1 school in the national universities category by the 2012 U.S. News & World Report college rankings...

in The Civil War in Louisiana (1963), "Butler hated Banks and was jealous of his political success and his 'reputation of being the best general selected from civil life.'" Nevertheless, Butler, "swallowing his bitter pill with a show of good grace" welcomed Banks to New Orleans and briefed him on civil and military affairs of importance. Gideon Welles

Gideon Welles

Gideon Welles was the United States Secretary of the Navy from 1861 to 1869. His buildup of the Navy to successfully execute blockades of Southern ports was a key component of Northern victory of the Civil War...

, secretary of the navy

United States Secretary of the Navy

The Secretary of the Navy of the United States of America is the head of the Department of the Navy, a component organization of the Department of Defense...

, doubted the wisdom of replacing Butler [a later Massachusetts governor] with Banks. According to historian Winters, "Welles's opinion of the military abilities of both men was very low, but he did not question Butler's skill as a 'police magistrate' in charge of civil affairs. Banks, he thought did not have 'the energy, power or ability of Butler.' He did have 'some ready qualities for civil administration,' but was less reckless and unscrupulous' and probably would not be able to hold a tight enough rein on the people" once placed under Union control."

Mrs. Banks joined her husband in New Orleans and held lavish dinner parties for the benefit of Union soldiers and their families. On April 12, 1864, she played the role of the "Goddess of Liberty" surrounded by all of the states of the reunited country. She did not then know of her husband's unhappy fate at the Battle of Mansfield

Battle of Mansfield

The Battle of Mansfield, also known as the Battle of Sabine Crossroads, occurred on April 8, 1864, in De Soto Parish, Louisiana. Confederate forces commanded by Richard Taylor attacked a Union army commanded by Nathaniel Banks a few miles outside the town of Mansfield, near Sabine Crossroads...

just three days earlier. By July 4, 1864, however, New Orleans had recovered from the Red River Campaign to hold another mammoth concert extolling the Union.

Banks issued orders to his men prohibiting pillage, but the undisciplined troops had chosen to disobey them, particularly when near a prosperous plantation. A soldier of the New York 114th wrote: "The men soon learned the pernicious habit of slyly leaving their places in the ranks when opposite a planter's house. ... Oftentimes a soldier can be found with such an enormous development of the organ of destructiveness that the most severe punishment cannot deter him from indulging in the breaking of mirrors, pianos, and the most costly furniture. Men of such reckless disposition are frequently guilty of the most horrible desecrations."

Under orders to ascend the Mississippi River

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

to join forces with Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

, who was then trying to capture Vicksburg

Vicksburg, Mississippi

Vicksburg is a city in Warren County, Mississippi, United States. It is the only city in Warren County. It is located northwest of New Orleans on the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers, and due west of Jackson, the state capital. In 1900, 14,834 people lived in Vicksburg; in 1910, 20,814; in 1920,...

, Banks first pushed a Confederate force up the Teche Bayou

Bayou Teche

The Bayou Teche is a waterway of great cultural significance in south central Louisiana in the United States. Bayou Teche was the Mississippi River's main course when it developed a delta about 2,800 to 4,500 years ago...

and marched to Alexandria, Louisiana

Alexandria, Louisiana

Alexandria is a city in and the parish seat of Rapides Parish, Louisiana, United States. It lies on the south bank of the Red River in almost the exact geographic center of the state. It is the principal city of the Alexandria metropolitan area which encompasses all of Rapides and Grant parishes....

, hauling off slaves, cotton, and cattle from a rich agricultural area.

Siege of Port Hudson

When the Confederates reduced their garrison at Port Hudson, LouisianaPort Hudson, Louisiana

Port Hudson is a small unincorporated community in East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana, United States. Located about northwest of Baton Rouge, it is most famous for an American Civil War battle known as the Siege of Port Hudson.-Geography:...

, on the Mississippi, he invested that place in May 1863. Two attempts to carry the works by storm during the Siege of Port Hudson

Siege of Port Hudson

The Siege of Port Hudson occurred from May 22 to July 9, 1863, when Union Army troops assaulted and then surrounded the Mississippi River town of Port Hudson, Louisiana, during the American Civil War....

, as at Vicksburg, were dismal failures. Port Hudson was the first time African American soldiers were used in a major Civil War battle, as permitted by Banks. Low on food and ammunition, the garrison surrendered on July 9, 1863, after receiving word that Vicksburg had fallen. The entire Mississippi River was then under Union control.

In the autumn of 1863, Banks organized two seaborne expeditions to Texas

Texas

Texas is the second largest U.S. state by both area and population, and the largest state by area in the contiguous United States.The name, based on the Caddo word "Tejas" meaning "friends" or "allies", was applied by the Spanish to the Caddo themselves and to the region of their settlement in...

, chiefly for the purpose of preventing the French in Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

from aiding the Confederates or occupying Texas. He eventually secured possession

Battle of Brownsville

The Battle of Brownsville took place on November 2-6, 1863 during the American Civil War. It was a successful effort on behalf of the Union Army to disrupt Confederate blockade runners along the Gulf Coast in Texas...

of the region near the mouth of the Rio Grande

Rio Grande

The Rio Grande is a river that flows from southwestern Colorado in the United States to the Gulf of Mexico. Along the way it forms part of the Mexico – United States border. Its length varies as its course changes...

and the Texas outer islands.

Red River Campaign

In 1863 Chief of Staff Henry Halleck continually promoted to Banks the Red River CampaignRed River Campaign

The Red River Campaign or Red River Expedition consisted of a series of battles fought along the Red River in Louisiana during the American Civil War from March 10 to May 22, 1864. The campaign was a Union initiative, fought between approximately 30,000 Union troops under the command of Maj. Gen....

, and implied that the other major commanders favored the expedition. Banks in 1863 had disagreed with the Red River plan, hoping instead to mount sea expeditions to capture the Galveston area and Mobile. His superior, Ulysses S. Grant, considered it a strategic distraction, as he wanted Banks to drive east to capture Mobile

Mobile, Alabama

Mobile is the third most populous city in the Southern US state of Alabama and is the county seat of Mobile County. It is located on the Mobile River and the central Gulf Coast of the United States. The population within the city limits was 195,111 during the 2010 census. It is the largest...

, Alabama

Alabama

Alabama is a state located in the southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama ranks 30th in total land area and ranks second in the size of its inland...

, as part of a coordinated series of offensives in the spring of 1864. When preparations for the 1864 Red River expedition were far advanced, Halleck wrote Banks he was withdrawing any suggestion as to action after receiving from Banks a detailed negative report about the operation. There is no evidence Halleck provided the negative report on the Red River to Grant, who was being asked for input on overall operations at the time. Halleck began referring to the Red River expedition as Banks's plan in keeping with an established pattern of deflecting responsibility.

The campaign lasted from March–May 1864; Banks' army was routed at the Battle of Mansfield

Battle of Mansfield

The Battle of Mansfield, also known as the Battle of Sabine Crossroads, occurred on April 8, 1864, in De Soto Parish, Louisiana. Confederate forces commanded by Richard Taylor attacked a Union army commanded by Nathaniel Banks a few miles outside the town of Mansfield, near Sabine Crossroads...

by General Richard Taylor

Richard Taylor (general)

Richard Taylor was a Confederate general in the American Civil War. He was the son of United States President Zachary Taylor and First Lady Margaret Taylor.-Early life:...

(son of former President Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor was the 12th President of the United States and an American military leader. Initially uninterested in politics, Taylor nonetheless ran as a Whig in the 1848 presidential election, defeating Lewis Cass...

) and retreated 20 miles to make a stand the next day at the Battle of Pleasant Hill

Battle of Pleasant Hill

The Battle of Pleasant Hill was fought on April 9, 1864, during the Red River Campaign of the American Civil War, near Pleasant Hill, Louisiana, between Union forces led by Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks and Confederate forces, led by Maj. Gen...

. They continued the retreat to Alexandria, where they rejoined with part of the Federal Inland Fleet. That naval force under David Dixon Porter

David Dixon Porter

David Dixon Porter was a member of one of the most distinguished families in the history of the United States Navy. Promoted as the second man to the rank of admiral, after his adoptive brother David G...

had joined the Red River Campaign to support the army and to take on cotton as lucrative prizes of war, and Banks had allowed rich speculators to come along for the gathering of cotton. The cooperating force was unable to arrive overland from Arkansas, two attached corps belonging to General William T. Sherman acted semi-independently, and the river had dangerously low water levels.

Part of Porter's large fleet became trapped above the falls at Alexandria by the low water. Banks and others approved a plan proposed by Joseph Bailey

Joseph Bailey (general)

Joseph Bailey was a civil engineer who served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War.-Early life:...

to build wing dams as a means to raise what little water was left in the channel. In ten days, 10,000 troops built two dams, and managed to rescue Porter's fleet, allowing all to retreat to the Mississippi River. After the campaign, just before General Sherman began his operations against Atlanta, Sherman said of the Red River campaign that it was "One damn blunder from beginning to end." On April 22, 1864, Grant wired Chief of Staff Halleck asking for Banks's removal. He was replaced by Edward Canby

Edward Canby

Edward Richard Sprigg Canby was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War, Reconstruction era, and the Indian Wars...

, who was promoted to Major General.

The Confederates held the Red River for the remainder of the war. They finally surrendered June 1865, two months after Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War....

sued for peace at Appomattox Court House

Appomattox Court House

The Appomattox Courthouse is the current courthouse in Appomattox, Virginia built in 1892. It is located in the middle of the state about three miles northwest of the Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, once known as Clover Hill - home of the original Old Appomattox Court House...

in Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

.

Administrative duties

While retaining administrative command of the Army of the Gulf from New Orleans, Banks went on leave in fall 1864 to the North. President Lincoln delegated him to lobby Congress through the winter for the president's reconstruction plans for LouisianaLouisiana

Louisiana is a state located in the southern region of the United States of America. Its capital is Baton Rouge and largest city is New Orleans. Louisiana is the only state in the U.S. with political subdivisions termed parishes, which are local governments equivalent to counties...

. Banks had earlier engineered the election victory of a moderate loyalist civilian government in Louisiana, inaugurated by elaborate celebrations he organized and funded. The secret presidential investigating commission headed by conservative Democrats William Farrar Smith

William Farrar Smith

William Farrar Smith , was a civil engineer, a member of the New York City police commission, and Union general in the American Civil War.-Early life:...

and James T. Brady in early 1865 devoted considerable effort to trying to connect Banks with vice and irregular trading permits in the New Orleans area. The somewhat one-sided final commission report, which did not specifically accuse him of wrongdoing, was never released. But Banks had definitely granted special favors without apparent compensation to men later connected to the Crédit Mobilier

Crédit Mobilier of America scandal

The Crédit Mobilier scandal of 1872 involved the Union Pacific Railroad and the Crédit Mobilier of America construction company in the building of the First Transcontinental Railroad. The distribution of Crédit Mobilier shares of stock by Congressman Oakes Ames along with cash bribes to...

scandal and to a few others of questionable reputation.

Postbellum career

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson was the 17th President of the United States . As Vice-President of the United States in 1865, he succeeded Abraham Lincoln following the latter's assassination. Johnson then presided over the initial and contentious Reconstruction era of the United States following the American...

. He was elected as a representative to Congress, serving from 1865 to 1873, when he held the positions of chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee and sometimes as chair of the Republican caucus. He played a key role in the final passage of the Alaska Purchase

Alaska purchase

The Alaska Purchase was the acquisition of the Alaska territory by the United States from Russia in 1867 by a treaty ratified by the Senate. The purchase, made at the initiative of United States Secretary of State William H. Seward, gained of new United States territory...

legislation, supported women's suffrage

Women's suffrage

Women's suffrage or woman suffrage is the right of women to vote and to run for office. The expression is also used for the economic and political reform movement aimed at extending these rights to women and without any restrictions or qualifications such as property ownership, payment of tax, or...

, and was one of the strongest early advocates of Manifest Destiny

Manifest Destiny

Manifest Destiny was the 19th century American belief that the United States was destined to expand across the continent. It was used by Democrat-Republicans in the 1840s to justify the war with Mexico; the concept was denounced by Whigs, and fell into disuse after the mid-19th century.Advocates of...

. Banks's financial records strongly suggest he received a large gratuity from the Russian minister after the Alaska legislation passed. Banks wanted the United States to acquire Canada and the Caribbean islands to reduce European influence in the region. He also served on the committee investigating the Crédit Mobilier scandal.

Unhappy with the administration of President Ulysses Grant, in 1872 he joined the Liberal-Republican revolt in support of Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley was an American newspaper editor, a founder of the Liberal Republican Party, a reformer, a politician, and an outspoken opponent of slavery...

. While Banks was campaigning across the North for Greeley, an opponent successfully gathered enough support in his Massachusetts district to defeat him as the joint Liberal-Republican and Democratic candidate. Banks thought his involvement with a start-up Kentucky railroad and other railroads would substitute for the political loss. But the Panic of 1873

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 triggered a severe international economic depression in both Europe and the United States that lasted until 1879, and even longer in some countries. The depression was known as the Great Depression until the 1930s, but is now known as the Long Depression...

doomed the railroad, and Banks went on the lecture circuit and was elected to the Massachusetts Senate.

In 1874, he was elected to Congress again as an independent and served the following two terms, again as a Republican (1875–1879). He was a member of the committee investigating the irregular 1876 elections in South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

. When he was defeated in 1878, the president appointed him as United States marshal

United States Marshals Service

The United States Marshals Service is a United States federal law enforcement agency within the United States Department of Justice . The office of U.S. Marshal is the oldest federal law enforcement office in the United States; it was created by the Judiciary Act of 1789...

for Massachusetts, a post he held from 1879 until 1888. That year, Banks was elected to Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

as a Republican.

During his final term, colleagues saw significant mental deterioration, and did not renominate him. He died at Waltham, Massachusetts

Waltham, Massachusetts

Waltham is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States, was an early center for the labor movement, and major contributor to the American Industrial Revolution. The original home of the Boston Manufacturing Company, the city was a prototype for 19th century industrial city planning,...

in 1894, and is buried there in Grove Hill Cemetery.

Legacy and honors

Fort BanksFort Banks (Massachusetts)

Fort Banks was a U.S. Coast Artillery fort located in Winthrop, Massachusetts. It served to defend Boston Harbor from enemy attack from the sea and was built in the 1890s during what is known as the Endicott period, a time in which the coast defenses of the United States were seriously expanded and...

in Winthrop, Massachusetts

Winthrop, Massachusetts

The Town of Winthrop is a municipality in Suffolk County, Massachusetts, United States. The population of Winthrop was 17,497 at the 2010 U.S. Census. It is an oceanside suburban community in Greater Boston situated at the north entrance to Boston Harbor and is very close to Logan International...

, built in the late 1890s, was named for him.

See also

- List of American Civil War generals

- List of Massachusetts generals in the American Civil War

- Massachusetts in the American Civil War