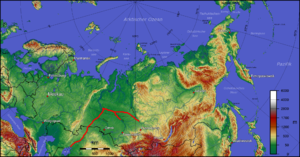

Northern river reversal

Encyclopedia

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, which "uselessly" drain into the Arctic Ocean

Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean, located in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Arctic north polar region, is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceanic divisions...

, southwards towards the populated agricultural areas of Central Asia

Central Asia

Central Asia is a core region of the Asian continent from the Caspian Sea in the west, China in the east, Afghanistan in the south, and Russia in the north...

, which lack water.

Research and planning work on the project started in the 1930s, and was carried out on a large scale in the 1960s through the early 1980s. The highly controversial project was abandoned in 1986, primarily for environmental reasons, without much actual construction work ever done.

Development of the river rerouting projects

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal , also known by the nickname "The Highway to India", is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Opened in November 1869 after 10 years of construction work, it allows water transportation between Europe and Asia without navigation...

and Panama

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal is a ship canal in Panama that joins the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean and is a key conduit for international maritime trade. Built from 1904 to 1914, the canal has seen annual traffic rise from about 1,000 ships early on to 14,702 vessels measuring a total of 309.6...

canals).

A century after Shrenk expressed his idea, the USSR Academy of Sciences held a conference investigating his ideas in November 1933. This conference stimulated interest that produced many serious engineering case studies trying to validate the possibility of the water return concept. Hydroproject

Hydroproject

Hydroproject is a Russian hydrotechnical design firm. Based in Moscow, it has a number of branches around the country. Its main activities are design of dams, hydroelectric stations, canals, sluices, etc....

, the dam and canal institute, led by Sergey Yakovlevich Zhuk began many of these studies.

The project of turning some of the flow of the northern rivers to the south was discussed, on a smaller scale, in the 1930s. In November 1933, a special conference of the USSR Academy of Sciences approved a plan for a "reconstruction of the Volga

Volga River

The Volga is the largest river in Europe in terms of length, discharge, and watershed. It flows through central Russia, and is widely viewed as the national river of Russia. Out of the twenty largest cities of Russia, eleven, including the capital Moscow, are situated in the Volga's drainage...

and its basin", which included the diversion into the Volga of some of the waters of the Pechora

Pechora River

The Pechora River is a river in northwest Russia which flows north into the Arctic Ocean on the west side of the Ural Mountains. It lies mostly in the Komi Republic but the northernmost part crosses the Nenets Autonomous Okrug. It is 1,809 km long and its basin is 322,000 square kilometers...

and the Northern Dvina

Northern Dvina

The Northern Dvina is a river in Northern Russia flowing through the Vologda Oblast and Arkhangelsk Oblast into the Dvina Bay of the White Sea. Along with the Pechora River to the east, it drains most of Northwest Russia into the Arctic Ocean...

- two rivers in the north of European Russia

European Russia

European Russia refers to the western areas of Russia that lie within Europe, comprising roughly 3,960,000 square kilometres , larger in area than India, and spanning across 40% of Europe. Its eastern border is defined by the Ural Mountains and in the south it is defined by the border with...

that flow into the seas of the Arctic Ocean. Research in that direction was then conducted by the Hydroproject

Hydroproject

Hydroproject is a Russian hydrotechnical design firm. Based in Moscow, it has a number of branches around the country. Its main activities are design of dams, hydroelectric stations, canals, sluices, etc....

, the dam and canal institute led by Sergey Yakovlevich Zhuk . Some design plans were developed by Zhuk's institute, but without much publicity or actual construction work.

In January 1961, several years after Zhuk's death, Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

presented a memo by Zhuk and another engineer, G. Russo, about the river rerouting plan to the Central Committee of the CPSU. Despite the ousting of Khrushchev in 1964, talks about the projects of turning the major rivers Pechora

Pechora River

The Pechora River is a river in northwest Russia which flows north into the Arctic Ocean on the west side of the Ural Mountains. It lies mostly in the Komi Republic but the northernmost part crosses the Nenets Autonomous Okrug. It is 1,809 km long and its basin is 322,000 square kilometers...

, Kama

Kama River

Kama is a major river in Russia, the longest left tributary of the Volga and the largest one in discharge; in fact, it is larger than the Volga before junction....

, Tobol, Ishim

Ishim River

Ishim River is a river running through Kazakhstan and Russia. Its length is 2,450 km , average discharge is 56,3 m³/s . It is a left tributary of the Irtysh River. The Ishim River is partly navigable in its lower reaches. The upper course of the Ishim passes through Astana, the capital of Kazakhstan...

, Irtysh

Irtysh

The Irtysh River is a river in Siberia and is the chief tributary of the Ob River. Its name means White River. Irtysh's main affluent is the Tobol River...

, and Ob

Ob River

The Ob River , also Obi, is a major river in western Siberia, Russia and is the world's seventh longest river. It is the westernmost of the three great Siberian rivers that flow into the Arctic Ocean .The Gulf of Ob is the world's longest estuary.-Names:The Ob is known to the Khanty people as the...

resumed in the late 1960s.

Some 120 institutes and agencies participated in the impact study coordinated by the Academy of Sciences; a dozen conferences were held on the matter. The promoters of the project claimed that extra food production due to the availability of Siberian water for irrigation in Central Asia could provide food for some 200,000,000 people.

The plans involved not only irrigation

Irrigation

Irrigation may be defined as the science of artificial application of water to the land or soil. It is used to assist in the growing of agricultural crops, maintenance of landscapes, and revegetation of disturbed soils in dry areas and during periods of inadequate rainfall...

but also the replenishing of the shrinking Aral Sea

Aral Sea

The Aral Sea was a lake that lay between Kazakhstan in the north and Karakalpakstan, an autonomous region of Uzbekistan, in the south...

and Caspian Sea

Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the largest enclosed body of water on Earth by area, variously classed as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. The sea has a surface area of and a volume of...

.

In the 1970s construction started to divert the Pechora and Kama Rivers toward the Volga and the Caspian Sea in the south-west of Russia. A 70-mile stretch was levelled with the help of nuclear explosives, and this novel land-clearance method drew sharp criticisms on environmental pollution grounds. In 1971, at a meeting of the International Atomic Energy Agency

International Atomic Energy Agency

The International Atomic Energy Agency is an international organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy, and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. The IAEA was established as an autonomous organization on 29 July 1957...

in Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

, the Soviets disclosed information about earthworks

Earthworks (engineering)

Earthworks are engineering works created through the moving or processing of quantities of soil or unformed rock.- Civil engineering use :Typical earthworks include roads, railway beds, causeways, dams, levees, canals, and berms...

on the route of the Pechora-Kama Canal

Pechora-Kama Canal

Pechora–Kama Canal , or sometimes Kama–Pechora Canal was a proposed canal intended to link up the basin of the Pechora River in the north of European Russia with the basin of the Kama, a tributary of the Volga...

using detonations of three 15-kiloton nuclear devices spaced 500 feet apart, claiming negligible radioactive fallout. However, no further construction work, nuclear or otherwise, was conducted on that canal.

It was estimated that 250 more nuclear detonations would have been required to complete the levelling for the channel if the procedure had been continued. Pollution on the surface was found to be manageable. In the US, expert opinion was divided with some endorsing this project; the physicist Glenn Werth, of the University of California's Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, stated that it was "both safe and economical". Others feared climatic cooling from reduced river water flow, while others thought that increased salinity would melt ice and cause warming. Further work on this irrigation canal was soon stopped.

In the 1980s at least 12 of the Arctic Ocean-bound rivers were proposed to be redirected to the south. At that time it was estimated that an additional freeze-up would occur to cut the brief northern growing season by two weeks if 37.8 billion extra cubic meters of water were returned annually to the European side of Russia and 60 billion cubic meters in Siberia. The adverse effect of climatic cooling was greatly feared and contributed much to the opposition at that time, and the scheme was not taken up. Severe problems were feared from the thick ice expected to remain well past winter in the proposed reservoirs. By delaying the spring thaw, it was feared, the prolonged freeze-up could cut the already brief northern growing season by two weeks. It was also feared that the prolonged winter weather would cause an increase in spring winds and reduce vital rains. More disturbing, some scientists cautioned that if the Arctic Ocean was not replenished by fresh water, it would get saltier and its freezing point would drop, the icecap would begin to melt, possibly starting a global warming trend. Other scientists feared that the opposite might occur: as the flow of warmer fresh water would be reduced, the polar ice might expand. A British climatologist, Michael Kelly of the University of East England, warned of the consequences: changes in polar winds and currents might reduce rainfall in the regions benefiting from the river redirection.

Criticism of the project and its abandonment

In 1986 a resolution "On the Cessation of the Work on the Partial Flow Transfer of Northern and Siberian Rivers" was passed by the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the CPSUPolitburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Politburo , known as the Presidium from 1952 to 1966, functioned as the central policymaking and governing body of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.-Duties and responsibilities:The...

, which halted the discussion on this matter for more than a decade. The Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

and then Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

have continued these studies with the other regional powers weighing the costs and benefits of turning Siberia's rivers back to the south and using the redirected water in Russia and Central Asian countries plus neighbouring regions of China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

for agriculture, household and industrial use, and perhaps also for rehabilitating water inflow to the Aral Sea

Aral Sea

The Aral Sea was a lake that lay between Kazakhstan in the north and Karakalpakstan, an autonomous region of Uzbekistan, in the south...

.

According to Aleksey Yablokov, President of the NGO Centre for Russian Environmental Policy, 5-7% redirection of the Ob's water could lead to long-lasting changes in the climate of the Arctic and elsewhere in Russia and he opposes these changes to the environment affected by Siberian water redirections to the south.. Despite the increase in Siberian rainfall, the redirection has become highly politicised and Yaroslav Ishutin, director of the Altai Krai Regional Department of Natural Resources and the Environment claims that the Ob has no water to spare and Siberia's water resources are threatened.

Calls for resumption of the project

In the early 21st century interest on this Siberian "water return" project was again resumed and the Central Asian states (President Nursultan NazarbayevNursultan Nazarbayev

Nursultan Abishuly Nazarbayev has served as the President of Kazakhstan since the nation received its independence in 1991, after the fall of the Soviet Union...

of Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan , officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country in Central Asia and Eastern Europe. Ranked as the ninth largest country in the world, it is also the world's largest landlocked country; its territory of is greater than Western Europe...

, President Islam Karimov of Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan , officially the Republic of Uzbekistan is a doubly landlocked country in Central Asia and one of the six independent Turkic states. It shares borders with Kazakhstan to the west and to the north, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to the east, and Afghanistan and Turkmenistan to the south....

as well as the Presidents of Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan , officially the Kyrgyz Republic is one of the world's six independent Turkic states . Located in Central Asia, landlocked and mountainous, Kyrgyzstan is bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, Tajikistan to the southwest and China to the east...

and Tajikistan

Tajikistan

Tajikistan , officially the Republic of Tajikistan , is a mountainous landlocked country in Central Asia. Afghanistan borders it to the south, Uzbekistan to the west, Kyrgyzstan to the north, and China to the east....

) held an informal summit with Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

and China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

to discuss the project. These proposals met with an enthusiastic response from one of Russia's most influential politicians at the time, Moscow

Moscow

Moscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

mayor

Mayor

In many countries, a Mayor is the highest ranking officer in the municipal government of a town or a large urban city....

Yury Luzhkov.

See also

- Water exports

- Chicago River reversal

- Great construction projects of communismGreat construction projects of communismGreat construction projects of communism was a term used for a series of ambitious construction projects undertaken in 1950s on the command of Joseph Stalin....

, other ambitious Soviet projects - Great Plan for the Transformation of Nature