.gif)

Ottoman–Venetian War (1570–1573)

Encyclopedia

The Fourth Ottoman–Venetian War, also known as the War of Cyprus was fought between 1570–1573. It was waged between the Ottoman Empire

and the Republic of Venice

, the latter joined by the Holy League, a coalition of Christian states formed under the auspices of the Pope

, which included Spain

(with Naples

and Sicily

), the Republic of Genoa

, the Duchy of Savoy

, the Knights Hospitaller

, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany

, and other Italian states.

The war, the preeminent episode of Sultan Selim II

's reign, began with the Ottoman invasion of the Venetian-held island of Cyprus

. The capital Nicosia

and several other towns fell quickly to the considerably superior Ottoman army, leaving only Famagusta

in Venetian hands. Christian reinforcements were delayed, and Famagusta eventually fell in August 1571 after a siege of 11 months. Two months later, at the Battle of Lepanto

, the united Christian fleet destroyed the Ottoman fleet, but was unable to take advantage of this victory. The Ottomans quickly rebuilt their naval forces, and Venice was forced to negotiate a separate peace, ceding Cyprus to the Ottomans and paying a tribute of 300,000 ducat

s.

had been under Venetian rule since 1489. Together with Crete

, it was one of the major overseas possessions

of the Republic. Its population in the mid-16th century is estimated at 160,000. Aside from its location, which allowed the control of the Levant

ine trade, the island possessed a profitable production of cotton and sugar. To safeguard their most distant colony, the Venetians paid an annual tribute of 8,000 ducats to the Mamluk

Sultans of Egypt

, and after their fall to the Ottomans

in 1517, the agreement was renewed with the Porte. Nevertheless, the island's strategic location in the Eastern Mediterranean, between the Ottoman heartland of Anatolia

and the newly won provinces of the Levant

and Egypt, made it a tempting target for future Ottoman expansion. In addition, the protection offered by the local Venetian authorities to Christian corsairs who harassed Muslim shipping, including the pilgrims

to Mecca

, rankled with the Ottoman leadership.

After concluding a prolonged war with the Habsburgs in 1568, the Ottomans were free to turn their attention to Cyprus. Sultan Selim II

had made the conquest of the island his first priority already before his accession in 1566, relegating Ottoman aid of the Morisco Revolt

against Spain and attacks against Portuguese activities in the Indian Ocean to a secondary priority. Despite the peace treaty with Venice, renewed as recently as 1567, and the opposition of Grand Vizier

Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, the war party at the Ottoman court prevailed. A favorable juridical opinion by the Sheikh ul-Islam

was secured, which declared that the breach of the treaty was justified since Cyprus was a "former land of Islam" (briefly in the 7th century) and had to be retaken. Money for the campaign was raised by the confiscation and resale of monasteries and churches of the Greek Orthodox Church

. The Sultan's old tutor, Lala Mustafa Pasha

, was appointed as commander of the expedition's land forces. Müezzinzade Ali Pasha, although totally inexperienced in naval matters, was appointed as Kapudan Pasha; he, however, assigned the able and experienced Piyale Pasha

as his principal aide.

On the Venetian side, Ottoman intentions had been clear, and an attack against Cyprus had been anticipated for some time. A war scare had broken out in 1564–1565, when the Ottomans eventually sailed for Malta

, and unease mounted again in late 1567 and early 1568, as the scale of the Ottoman naval buildup became apparent. The defenses of Cyprus, Crete

, Corfu

and other Venetian possessions were upgraded in the 1560s, employing the services of the noted military engineer Sforza Pallavicini. Their garrisons were increased, and attempts were made to make the isolated holdings of Crete and Cyprus more self-sufficient by the construction of foundries and gunpowder mills. However, it was widely recognized that, unaided, Cyprus could not hold for long. Its exposed and isolated location so far from Venice, surrounded by Ottoman territory, put it "in the wolf's mouth" as one contemporary historian wrote. In the event, lack of supplies and even gunpowder would play a critical role in the fall of the Venetian forts to the Ottomans. Another problem for Venice was the attitude of the island's population. The harsh treatment and oppressive taxation of the local orthodox Greek population by the Catholic Venetians had caused great resentment, so that their sympathies generally laid with the Ottomans.

By early 1570, the Ottoman preparations and the warnings sent by the Venetian bailo

at Constantinople, Marco Antonio Barbaro

, had convinced the Signoria that war was imminent. Reinforcements and money were sent post-haste to Crete and Cyprus. In March 1570, an Ottoman envoy was sent to Venice, bearing an ultimatum that demanded the immediate cession of Cyprus. Although some voices were raised in the Venetian Signoria

advocating the cession of the island in exchange for land in Dalmatia

and further trading privileges, the hope of assistance from the other Christian states stiffened the Republic's resolve, and the ultimatum was categorically rejected.

on the island's southern shore on 3 July, and marched towards the capital, Nicosia

. The Venetians had debated opposing the landing, but in the face of the superior Ottoman artillery, and the fact that a defeat would mean the annihilation of the island's defensive force, it was decided to withdraw to the forts and hold out until reinforcements arrived. The Siege of Nicosia began on 22 July and lasted for seven weeks, until 9 September. The city's newly constructed trace italienne walls of packed earth withstood the Ottoman bombardment well. The Ottomans, under Lala Mustafa Pasha, dug trenches towards the walls, and gradually filled the surrounding ditch, while constant volleys of arquebus

fire covered the sappers' work. Finally, the 45th assault, on 9 September, succeeded in breaching the walls after the defenders had exhausted their ammunition. A massacre of the city's 20,000 inhabitants ensued. Even the city's pigs, regarded as unclean

by Muslims, were killed, and only women and boys who were captured to be sold as slaves were spared. A combined Christian fleet of 200 vessels, composed of Venetian (under Girolamo Zane), Papal (under Marcantonio Colonna

) and Neapolitan/Genoese/Spanish (under Giovanni Andrea Doria

) squadrons that had belatedly been assembled at Crete by late August and was sailing towards Cyprus, turned back when it received news of Nicosia's fall.

Following the fall of Nicosia, the fortress of Kyrenia

in the north surrendered without resistance, and on 15 September, the Turkish cavalry appeared before the last Venetian stronghold, Famagusta

. At this point already, overall Venetian losses (including the local population) were estimated by contemporaries at 56,000 killed or taken prisoner. The Venetian defenders of Famagusta numbered about 8,500 men with 90 artillery pieces and were commanded by Marco Antonio Bragadin

. They would hold out for 11 months against a force that would come to number 200,000 men, with 145 guns, providing the time needed by the Pope to cobble together an anti-Ottoman league from the reluctant Christian European states. The Ottomans set up their guns on 1 September. Over the following months, they proceeded to dig a huge network of crisscrossing trenches for a depth of three miles around the fortress, which provided shelter for the Ottoman troops. As the siege trenches neared the fortress and came within artillery range of the walls, ten forts of timber and packed earth and bales of cotton were erected. The Ottomans however lacked the naval strength to completely blockade the city from sea as well, and the Venetians were able to resupply it and bring in reinforcements. After news of such a resupply in January reached the Sultan, he recalled Piyale Pasha and left Lala Mustafa alone in charge of the siege. At the same time, an initiative by Sokollu Mehmed Pasha to achieve a separate peace with Venice, foundered. Thus on 12 May 1571, the intensive bombardment of Famagusta's fortifications began, and on 1 August, with ammunition and supplies exhausted, the garrison surrendered the city. The siege cost the Ottomans some 50,000 casualties.

, having just concluded peace with the Ottomans, was not keen to break it. France was traditionally on friendly terms with the Ottomans and hostile to the Spanish, and the Poles were troubled by Muscovy. The Spanish Habsburgs, the greatest Christian power in the Mediterranean, were not initially interested in helping the Republic and resentful of Venice's refusal to send aid during the Siege of Malta

in 1565. In addition, Philip II of Spain

wanted to focus his strength against the Barbary states of North Africa

. The Spanish reluctance to engage on the side of the Republic, together with Doria's reluctance to endanger his fleet, had already disastrously delayed the joint naval effort in 1570. However, with the energetic mediation of Pope Pius V, an alliance against the Ottomans, the "Holy League", was concluded on 15 May 1571, which stipulated the assembly of a fleet of 200 galleys, 100 supply vessels and a force of 50,000 men. To secure Spanish assent, the treaty also included a Venetian promise to aid Spain in North Africa.

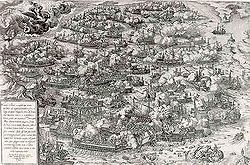

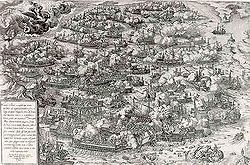

On 7 October, the two fleets engaged in a battle off Lepanto

On 7 October, the two fleets engaged in a battle off Lepanto

, which resulted in a crushing victory for the Christian fleet, while the Ottoman fleet was largely destroyed. In popular perception, the battle itself became known as one of the decisive turning points in the long Ottoman-Christian struggle, as it ended the Ottoman naval hegemony established at the Battle of Preveza

in 1538. Its immediate results however were minimal: the harsh winter that followed precluded any offensive actions on behalf of the Holy League, while the Ottomans used the respite to feverishly rebuild their naval strength. At the same time, Venice suffered losses in Dalmatia

, where the Ottomans advanced, taking several inland positions and the island of Brazza (Brač

). The strategic situation was graphically summed up later by the Ottoman Grand Vizier to the Venetian bailo: "[in defeating our fleet] you have shaved our beard, but it will grow again, but [in conquering Cyprus] we have severed your arm and you will never find another."

The following year, as the allied Christian fleet resumed operations, it faced a renewed Ottoman navy under Kılıç Ali Pasha. Both fleets cruised and skirmished repeatedly off the Peloponnese, but no decisive engagement resulted. The diverging interests of the League members began to show, and the alliance began to fail. In 1573, the Holy League fleet failed to sail altogether; instead, Don John attacked and took Tunis

, although retaken by the Ottomans in 1574. Venice, eager to cut her losses and resume the trade with the Ottoman Empire, initiated unilateral negotiations with the Porte.

n border between the two powers was restored to its 1570 status quo ante

. Peace would continue between the two states until 1645, when a long war over Crete

would break out. Cyprus itself remained under Ottoman rule

until 1878, when it was ceded to Britain

as a protectorate

. Ottoman suzerainty

continued until the outbreak of World War I

, when the island was annexed by Britain, becoming a crown colony

in 1925.

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

and the Republic of Venice

Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice or Venetian Republic was a state originating from the city of Venice in Northeastern Italy. It existed for over a millennium, from the late 7th century until 1797. It was formally known as the Most Serene Republic of Venice and is often referred to as La Serenissima, in...

, the latter joined by the Holy League, a coalition of Christian states formed under the auspices of the Pope

Pope

The Pope is the Bishop of Rome, a position that makes him the leader of the worldwide Catholic Church . In the Catholic Church, the Pope is regarded as the successor of Saint Peter, the Apostle...

, which included Spain

Habsburg Spain

Habsburg Spain refers to the history of Spain over the 16th and 17th centuries , when Spain was ruled by the major branch of the Habsburg dynasty...

(with Naples

Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples, comprising the southern part of the Italian peninsula, was the remainder of the old Kingdom of Sicily after secession of the island of Sicily as a result of the Sicilian Vespers rebellion of 1282. Known to contemporaries as the Kingdom of Sicily, it is dubbed Kingdom of...

and Sicily

Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily was a state that existed in the south of Italy from its founding by Roger II in 1130 until 1816. It was a successor state of the County of Sicily, which had been founded in 1071 during the Norman conquest of southern Italy...

), the Republic of Genoa

Republic of Genoa

The Most Serene Republic of Genoa |Ligurian]]: Repúbrica de Zêna) was an independent state from 1005 to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italian coast, as well as Corsica from 1347 to 1768, and numerous other territories throughout the Mediterranean....

, the Duchy of Savoy

Duchy of Savoy

From 1416 to 1847, the House of Savoy ruled the eponymous Duchy of Savoy . The Duchy was a state in the northern part of the Italian Peninsula, with some territories that are now in France. It was a continuation of the County of Savoy...

, the Knights Hospitaller

Knights Hospitaller

The Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta , also known as the Sovereign Military Order of Malta , Order of Malta or Knights of Malta, is a Roman Catholic lay religious order, traditionally of military, chivalrous, noble nature. It is the world's...

, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany

Grand Duchy of Tuscany

The Grand Duchy of Tuscany was a central Italian monarchy that existed, with interruptions, from 1569 to 1859, replacing the Duchy of Florence. The grand duchy's capital was Florence...

, and other Italian states.

The war, the preeminent episode of Sultan Selim II

Selim II

Selim II Sarkhosh Hashoink , also known as "Selim the Sot " or "Selim the Drunkard"; and as "Sarı Selim" or "Selim the Blond", was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1566 until his death in 1574.-Early years:He was born in Constantinople a son of Suleiman the...

's reign, began with the Ottoman invasion of the Venetian-held island of Cyprus

Cyprus

Cyprus , officially the Republic of Cyprus , is a Eurasian island country, member of the European Union, in the Eastern Mediterranean, east of Greece, south of Turkey, west of Syria and north of Egypt. It is the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea.The earliest known human activity on the...

. The capital Nicosia

Nicosia

Nicosia from , known locally as Lefkosia , is the capital and largest city in Cyprus, as well as its main business center. Nicosia is the only divided capital in the world, with the southern and the northern portions divided by a Green Line...

and several other towns fell quickly to the considerably superior Ottoman army, leaving only Famagusta

Famagusta

Famagusta is a city on the east coast of Cyprus and is capital of the Famagusta District. It is located east of Nicosia, and possesses the deepest harbour of the island.-Name:...

in Venetian hands. Christian reinforcements were delayed, and Famagusta eventually fell in August 1571 after a siege of 11 months. Two months later, at the Battle of Lepanto

Battle of Lepanto (1571)

The Battle of Lepanto took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League, a coalition of Catholic maritime states, decisively defeated the main fleet of the Ottoman Empire in five hours of fighting on the northern edge of the Gulf of Patras, off western Greece...

, the united Christian fleet destroyed the Ottoman fleet, but was unable to take advantage of this victory. The Ottomans quickly rebuilt their naval forces, and Venice was forced to negotiate a separate peace, ceding Cyprus to the Ottomans and paying a tribute of 300,000 ducat

Ducat

The ducat is a gold coin that was used as a trade coin throughout Europe before World War I. Its weight is 3.4909 grams of .986 gold, which is 0.1107 troy ounce, actual gold weight...

s.

Background

The large and wealthy island of CyprusCyprus

Cyprus , officially the Republic of Cyprus , is a Eurasian island country, member of the European Union, in the Eastern Mediterranean, east of Greece, south of Turkey, west of Syria and north of Egypt. It is the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea.The earliest known human activity on the...

had been under Venetian rule since 1489. Together with Crete

Crete

Crete is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, and one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece. It forms a significant part of the economy and cultural heritage of Greece while retaining its own local cultural traits...

, it was one of the major overseas possessions

Stato da Màr

The Stato da Màr or Domini da Màr was the name given to the Republic of Venice's maritime and overseas possessions, including Istria, Dalmatia, Negroponte, the Morea , the Aegean islands of the Duchy of the Archipelago, and the islands of Crete and Cyprus...

of the Republic. Its population in the mid-16th century is estimated at 160,000. Aside from its location, which allowed the control of the Levant

Levant

The Levant or ) is the geographic region and culture zone of the "eastern Mediterranean littoral between Anatolia and Egypt" . The Levant includes most of modern Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Israel, the Palestinian territories, and sometimes parts of Turkey and Iraq, and corresponds roughly to the...

ine trade, the island possessed a profitable production of cotton and sugar. To safeguard their most distant colony, the Venetians paid an annual tribute of 8,000 ducats to the Mamluk

Mamluk

A Mamluk was a soldier of slave origin, who were predominantly Cumans/Kipchaks The "mamluk phenomenon", as David Ayalon dubbed the creation of the specific warrior...

Sultans of Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

, and after their fall to the Ottomans

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

in 1517, the agreement was renewed with the Porte. Nevertheless, the island's strategic location in the Eastern Mediterranean, between the Ottoman heartland of Anatolia

Anatolia

Anatolia is a geographic and historical term denoting the westernmost protrusion of Asia, comprising the majority of the Republic of Turkey...

and the newly won provinces of the Levant

Levant

The Levant or ) is the geographic region and culture zone of the "eastern Mediterranean littoral between Anatolia and Egypt" . The Levant includes most of modern Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Israel, the Palestinian territories, and sometimes parts of Turkey and Iraq, and corresponds roughly to the...

and Egypt, made it a tempting target for future Ottoman expansion. In addition, the protection offered by the local Venetian authorities to Christian corsairs who harassed Muslim shipping, including the pilgrims

Hajj

The Hajj is the pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia. It is one of the largest pilgrimages in the world, and is the fifth pillar of Islam, a religious duty that must be carried out at least once in their lifetime by every able-bodied Muslim who can afford to do so...

to Mecca

Mecca

Mecca is a city in the Hijaz and the capital of Makkah province in Saudi Arabia. The city is located inland from Jeddah in a narrow valley at a height of above sea level...

, rankled with the Ottoman leadership.

After concluding a prolonged war with the Habsburgs in 1568, the Ottomans were free to turn their attention to Cyprus. Sultan Selim II

Selim II

Selim II Sarkhosh Hashoink , also known as "Selim the Sot " or "Selim the Drunkard"; and as "Sarı Selim" or "Selim the Blond", was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1566 until his death in 1574.-Early years:He was born in Constantinople a son of Suleiman the...

had made the conquest of the island his first priority already before his accession in 1566, relegating Ottoman aid of the Morisco Revolt

Morisco Revolt

The Morisco Revolt , also known as War of Las Alpujarras or Revolt of Las Alpujarras, in what is now Andalusia in southern Spain, was a rebellion against the Crown of Castile by the remaining Muslim converts to Christianity from the Kingdom of Granada.-The defeat of Muslim Spain:In the wake of the...

against Spain and attacks against Portuguese activities in the Indian Ocean to a secondary priority. Despite the peace treaty with Venice, renewed as recently as 1567, and the opposition of Grand Vizier

Grand Vizier

Grand Vizier, in Turkish Vezir-i Azam or Sadr-ı Azam , deriving from the Arabic word vizier , was the greatest minister of the Sultan, with absolute power of attorney and, in principle, dismissable only by the Sultan himself...

Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, the war party at the Ottoman court prevailed. A favorable juridical opinion by the Sheikh ul-Islam

Sheikh ul-Islam

Shaykh al-Islām is a title of superior authority in the issues of Islam....

was secured, which declared that the breach of the treaty was justified since Cyprus was a "former land of Islam" (briefly in the 7th century) and had to be retaken. Money for the campaign was raised by the confiscation and resale of monasteries and churches of the Greek Orthodox Church

Greek Orthodox Church

The Greek Orthodox Church is the body of several churches within the larger communion of Eastern Orthodox Christianity sharing a common cultural tradition whose liturgy is also traditionally conducted in Koine Greek, the original language of the New Testament...

. The Sultan's old tutor, Lala Mustafa Pasha

Lala Kara Mustafa Pasha

Lala Kara Mustafa Pasha was an Ottoman general and Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire.He had risen to the position of Beylerbey of Damascus and then to that of Fifth Vizier...

, was appointed as commander of the expedition's land forces. Müezzinzade Ali Pasha, although totally inexperienced in naval matters, was appointed as Kapudan Pasha; he, however, assigned the able and experienced Piyale Pasha

Piyale Pasha

Piyale Pasha , born in Viganj on the Pelješac peninsula, was a Croatian Ottoman admiral between 1553 and 1567 and an Ottoman Vizier after 1568. He was also known as Piale Pasha in the West or Pialí Bajá in Spain; )....

as his principal aide.

On the Venetian side, Ottoman intentions had been clear, and an attack against Cyprus had been anticipated for some time. A war scare had broken out in 1564–1565, when the Ottomans eventually sailed for Malta

Siege of Malta (1565)

The Siege of Malta took place in 1565 when the Ottoman Empire invaded the island, then held by the Knights Hospitaller .The Knights, together with between 4-5,000 Maltese men,...

, and unease mounted again in late 1567 and early 1568, as the scale of the Ottoman naval buildup became apparent. The defenses of Cyprus, Crete

Crete

Crete is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, and one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece. It forms a significant part of the economy and cultural heritage of Greece while retaining its own local cultural traits...

, Corfu

Corfu

Corfu is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea. It is the second largest of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the edge of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The island is part of the Corfu regional unit, and is administered as a single municipality. The...

and other Venetian possessions were upgraded in the 1560s, employing the services of the noted military engineer Sforza Pallavicini. Their garrisons were increased, and attempts were made to make the isolated holdings of Crete and Cyprus more self-sufficient by the construction of foundries and gunpowder mills. However, it was widely recognized that, unaided, Cyprus could not hold for long. Its exposed and isolated location so far from Venice, surrounded by Ottoman territory, put it "in the wolf's mouth" as one contemporary historian wrote. In the event, lack of supplies and even gunpowder would play a critical role in the fall of the Venetian forts to the Ottomans. Another problem for Venice was the attitude of the island's population. The harsh treatment and oppressive taxation of the local orthodox Greek population by the Catholic Venetians had caused great resentment, so that their sympathies generally laid with the Ottomans.

By early 1570, the Ottoman preparations and the warnings sent by the Venetian bailo

Baylo

A bailo, also spelled baylo, was a diplomat who oversaw the affairs of the Venetians in Constantinople, and was a permanent fixture in Constantinople around 1454...

at Constantinople, Marco Antonio Barbaro

Marcantonio Barbaro

Marcantonio Barbaro was an Italian diplomat of the Republic of Venice.-Family:He was born in Venice into the aristocratic Barbaro family...

, had convinced the Signoria that war was imminent. Reinforcements and money were sent post-haste to Crete and Cyprus. In March 1570, an Ottoman envoy was sent to Venice, bearing an ultimatum that demanded the immediate cession of Cyprus. Although some voices were raised in the Venetian Signoria

Signoria of Venice

The Signoria of Venice was the supreme body of government of the Republic of Venice. The original Greek name of the family was Spandounes...

advocating the cession of the island in exchange for land in Dalmatia

Dalmatia

Dalmatia is a historical region on the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea. It stretches from the island of Rab in the northwest to the Bay of Kotor in the southeast. The hinterland, the Dalmatian Zagora, ranges from fifty kilometers in width in the north to just a few kilometers in the south....

and further trading privileges, the hope of assistance from the other Christian states stiffened the Republic's resolve, and the ultimatum was categorically rejected.

Ottoman conquest of Cyprus

On 27 June, the invasion force, some 350 ships and 60,000 men, set sail for Cyprus. It landed unopposed at Salines,near LarnacaLarnaca

Larnaca, is the third largest city on the southern coast of Cyprus after Nicosia and Limassol. It has a population of 72,000 and is the island's second largest commercial port and an important tourist resort...

on the island's southern shore on 3 July, and marched towards the capital, Nicosia

Nicosia

Nicosia from , known locally as Lefkosia , is the capital and largest city in Cyprus, as well as its main business center. Nicosia is the only divided capital in the world, with the southern and the northern portions divided by a Green Line...

. The Venetians had debated opposing the landing, but in the face of the superior Ottoman artillery, and the fact that a defeat would mean the annihilation of the island's defensive force, it was decided to withdraw to the forts and hold out until reinforcements arrived. The Siege of Nicosia began on 22 July and lasted for seven weeks, until 9 September. The city's newly constructed trace italienne walls of packed earth withstood the Ottoman bombardment well. The Ottomans, under Lala Mustafa Pasha, dug trenches towards the walls, and gradually filled the surrounding ditch, while constant volleys of arquebus

Arquebus

The arquebus , or "hook tube", is an early muzzle-loaded firearm used in the 15th to 17th centuries. The word was originally modeled on the German hakenbüchse; this produced haquebute...

fire covered the sappers' work. Finally, the 45th assault, on 9 September, succeeded in breaching the walls after the defenders had exhausted their ammunition. A massacre of the city's 20,000 inhabitants ensued. Even the city's pigs, regarded as unclean

Haraam

Haraam is an Arabic term meaning "forbidden", or "sacred". In Islam it is used to refer to anything that is prohibited by the word of Allah in the Qur'an or the Hadith Qudsi. Haraam is the highest status of prohibition given to anything that would result in sin when a Muslim commits it...

by Muslims, were killed, and only women and boys who were captured to be sold as slaves were spared. A combined Christian fleet of 200 vessels, composed of Venetian (under Girolamo Zane), Papal (under Marcantonio Colonna

Marcantonio Colonna

Marcantonio II Colonna , Duke and Prince of Paliano, was an Italian general and admiral.-Biography:...

) and Neapolitan/Genoese/Spanish (under Giovanni Andrea Doria

Giovanni Andrea Doria

Giovanni Andrea Doria, also Giannandrea Doria , was an Italian admiral from Genoa. He was the son of Giannettino Doria and the great-nephew of the famed Genoese admiral Andrea Doria, by whom he was later adopted...

) squadrons that had belatedly been assembled at Crete by late August and was sailing towards Cyprus, turned back when it received news of Nicosia's fall.

Following the fall of Nicosia, the fortress of Kyrenia

Kyrenia

Kyrenia is a town on the northern coast of Cyprus, noted for its historic harbour and castle. Internationally recognised as part of the Republic of Cyprus, Kyrenia has been under Turkish control since the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974...

in the north surrendered without resistance, and on 15 September, the Turkish cavalry appeared before the last Venetian stronghold, Famagusta

Famagusta

Famagusta is a city on the east coast of Cyprus and is capital of the Famagusta District. It is located east of Nicosia, and possesses the deepest harbour of the island.-Name:...

. At this point already, overall Venetian losses (including the local population) were estimated by contemporaries at 56,000 killed or taken prisoner. The Venetian defenders of Famagusta numbered about 8,500 men with 90 artillery pieces and were commanded by Marco Antonio Bragadin

Marco Antonio Bragadin

Marco Antonio Bragadin, also Marcantonio Bragadin was an Italian lawyer and military officer of the Republic of Venice....

. They would hold out for 11 months against a force that would come to number 200,000 men, with 145 guns, providing the time needed by the Pope to cobble together an anti-Ottoman league from the reluctant Christian European states. The Ottomans set up their guns on 1 September. Over the following months, they proceeded to dig a huge network of crisscrossing trenches for a depth of three miles around the fortress, which provided shelter for the Ottoman troops. As the siege trenches neared the fortress and came within artillery range of the walls, ten forts of timber and packed earth and bales of cotton were erected. The Ottomans however lacked the naval strength to completely blockade the city from sea as well, and the Venetians were able to resupply it and bring in reinforcements. After news of such a resupply in January reached the Sultan, he recalled Piyale Pasha and left Lala Mustafa alone in charge of the siege. At the same time, an initiative by Sokollu Mehmed Pasha to achieve a separate peace with Venice, foundered. Thus on 12 May 1571, the intensive bombardment of Famagusta's fortifications began, and on 1 August, with ammunition and supplies exhausted, the garrison surrendered the city. The siege cost the Ottomans some 50,000 casualties.

The Holy League

As the Ottoman army campaigned in Cyprus, Venice tried to find allies. The Holy Roman EmperorHoly Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor is a term used by historians to denote a medieval ruler who, as German King, had also received the title of "Emperor of the Romans" from the Pope...

, having just concluded peace with the Ottomans, was not keen to break it. France was traditionally on friendly terms with the Ottomans and hostile to the Spanish, and the Poles were troubled by Muscovy. The Spanish Habsburgs, the greatest Christian power in the Mediterranean, were not initially interested in helping the Republic and resentful of Venice's refusal to send aid during the Siege of Malta

Siege of Malta (1565)

The Siege of Malta took place in 1565 when the Ottoman Empire invaded the island, then held by the Knights Hospitaller .The Knights, together with between 4-5,000 Maltese men,...

in 1565. In addition, Philip II of Spain

Philip II of Spain

Philip II was King of Spain, Portugal, Naples, Sicily, and, while married to Mary I, King of England and Ireland. He was lord of the Seventeen Provinces from 1556 until 1581, holding various titles for the individual territories such as duke or count....

wanted to focus his strength against the Barbary states of North Africa

North Africa

North Africa or Northern Africa is the northernmost region of the African continent, linked by the Sahara to Sub-Saharan Africa. Geopolitically, the United Nations definition of Northern Africa includes eight countries or territories; Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, South Sudan, Sudan, Tunisia, and...

. The Spanish reluctance to engage on the side of the Republic, together with Doria's reluctance to endanger his fleet, had already disastrously delayed the joint naval effort in 1570. However, with the energetic mediation of Pope Pius V, an alliance against the Ottomans, the "Holy League", was concluded on 15 May 1571, which stipulated the assembly of a fleet of 200 galleys, 100 supply vessels and a force of 50,000 men. To secure Spanish assent, the treaty also included a Venetian promise to aid Spain in North Africa.

Lepanto and the failure of the League

According to the terms of the new alliance, during the late summer, the Christian fleet assembled at Messina, under the command of Don John of Austria, who arrived on 23 August. By that time, however, Famagusta had fallen, and any effort to save Cyprus was meaningless. However, as it was sailing down the Ionian Sea, the combined Christian fleet came upon the Ottoman fleet, commanded by Müezzinzade Ali Pasha, which had anchored at Lepanto (Nafpaktos), near the entrance of the Corinthian Gulf.

Battle of Lepanto (1571)

The Battle of Lepanto took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League, a coalition of Catholic maritime states, decisively defeated the main fleet of the Ottoman Empire in five hours of fighting on the northern edge of the Gulf of Patras, off western Greece...

, which resulted in a crushing victory for the Christian fleet, while the Ottoman fleet was largely destroyed. In popular perception, the battle itself became known as one of the decisive turning points in the long Ottoman-Christian struggle, as it ended the Ottoman naval hegemony established at the Battle of Preveza

Battle of Preveza

The naval Battle of Preveza took place on 28 September 1538 near Preveza in northwestern Greece between an Ottoman fleet and that of a Christian alliance assembled by Pope Paul III.-Background:...

in 1538. Its immediate results however were minimal: the harsh winter that followed precluded any offensive actions on behalf of the Holy League, while the Ottomans used the respite to feverishly rebuild their naval strength. At the same time, Venice suffered losses in Dalmatia

Dalmatia

Dalmatia is a historical region on the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea. It stretches from the island of Rab in the northwest to the Bay of Kotor in the southeast. The hinterland, the Dalmatian Zagora, ranges from fifty kilometers in width in the north to just a few kilometers in the south....

, where the Ottomans advanced, taking several inland positions and the island of Brazza (Brač

Brac

Brač is an island in the Adriatic Sea within Croatia, with an area of 396 km², making it the largest island in Dalmatia, and the third largest in the Adriatic. Its tallest peak, Vidova Gora, or Mount St. Vid, stands at 778 m, making it the highest island point in the Adriatic...

). The strategic situation was graphically summed up later by the Ottoman Grand Vizier to the Venetian bailo: "[in defeating our fleet] you have shaved our beard, but it will grow again, but [in conquering Cyprus] we have severed your arm and you will never find another."

The following year, as the allied Christian fleet resumed operations, it faced a renewed Ottoman navy under Kılıç Ali Pasha. Both fleets cruised and skirmished repeatedly off the Peloponnese, but no decisive engagement resulted. The diverging interests of the League members began to show, and the alliance began to fail. In 1573, the Holy League fleet failed to sail altogether; instead, Don John attacked and took Tunis

Tunis

Tunis is the capital of both the Tunisian Republic and the Tunis Governorate. It is Tunisia's largest city, with a population of 728,453 as of 2004; the greater metropolitan area holds some 2,412,500 inhabitants....

, although retaken by the Ottomans in 1574. Venice, eager to cut her losses and resume the trade with the Ottoman Empire, initiated unilateral negotiations with the Porte.

Peace settlement and aftermath

Marco Antonio Barbaro, the Venetian bailo who had been imprisoned since 1570, conducted the negotiations. In view of the Republic's inability to regain Cyprus, the resulting treaty, signed on 7 March 1573, confirmed the new state of affairs: Cyprus became an Ottoman province, Venice paid an indemnity of 300,000 ducats, and the DalmatiaDalmatia

Dalmatia is a historical region on the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea. It stretches from the island of Rab in the northwest to the Bay of Kotor in the southeast. The hinterland, the Dalmatian Zagora, ranges from fifty kilometers in width in the north to just a few kilometers in the south....

n border between the two powers was restored to its 1570 status quo ante

Status quo ante

Status quo ante is Latin for "the way things were before" and incorporates the term status quo. In law, it refers to the objective of a temporary restraining order or a rescission in which the situation is restored to "the state in which previously" it existed...

. Peace would continue between the two states until 1645, when a long war over Crete

Cretan War (1645–1669)

The Cretan War or War of Candia , as the Fifth Ottoman–Venetian War is better known, was a conflict between the Republic of Venice and her allies against the Ottoman Empire and the Barbary States, fought over the island of Crete, Venice's largest and richest overseas possession...

would break out. Cyprus itself remained under Ottoman rule

Cyprus under the Ottoman Empire

The Eyalet of Cyprus was created in 1571, and changed its status frequently. It was a sanjak of the Eyalet of the Archipelago from 1660 to 1703, and again from 1784 onwards; a fief of the Grand Vizier , and again an eyalet for the short period 1745-1748.- Ottoman raids and conquest :Throughout the...

until 1878, when it was ceded to Britain

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

as a protectorate

Protectorate

In history, the term protectorate has two different meanings. In its earliest inception, which has been adopted by modern international law, it is an autonomous territory that is protected diplomatically or militarily against third parties by a stronger state or entity...

. Ottoman suzerainty

Suzerainty

Suzerainty occurs where a region or people is a tributary to a more powerful entity which controls its foreign affairs while allowing the tributary vassal state some limited domestic autonomy. The dominant entity in the suzerainty relationship, or the more powerful entity itself, is called a...

continued until the outbreak of World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, when the island was annexed by Britain, becoming a crown colony

Crown colony

A Crown colony, also known in the 17th century as royal colony, was a type of colonial administration of the English and later British Empire....

in 1925.