Pendle witch trials

Encyclopedia

Witch-hunt

A witch-hunt is a search for witches or evidence of witchcraft, often involving moral panic, mass hysteria and lynching, but in historical instances also legally sanctioned and involving official witchcraft trials...

in English history, and some of the best recorded of the 17th century. The twelve accused lived in the area around Pendle Hill

Pendle Hill

Pendle Hill is located in the north-east of Lancashire, England, near the towns of Burnley, Nelson, Colne, Clitheroe and Padiham, an area known as Pendleside. Its summit is above mean sea level. It gives its name to the Borough of Pendle. It is an isolated hill, separated from the Pennines to the...

in Lancashire

Lancashire

Lancashire is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in the North West of England. It takes its name from the city of Lancaster, and is sometimes known as the County of Lancaster. Although Lancaster is still considered to be the county town, Lancashire County Council is based in Preston...

, and were charged with the murders of ten people by the use of witchcraft

Witchcraft

Witchcraft, in historical, anthropological, religious, and mythological contexts, is the alleged use of supernatural or magical powers. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft...

. All but two were tried at Lancaster

Lancaster, Lancashire

Lancaster is the county town of Lancashire, England. It is situated on the River Lune and has a population of 45,952. Lancaster is a constituent settlement of the wider City of Lancaster, local government district which has a population of 133,914 and encompasses several outlying towns, including...

Assizes

Assizes

Assize or Assizes may refer to:Assize or Assizes may refer to:Assize or Assizes may refer to::;in common law countries :::*assizes , an obsolete judicial inquest...

on 18–19 August 1612, along with the Samlesbury witches

Samlesbury witches

The Samlesbury witches were three women from the Lancashire village of Samlesbury Jane Southworth, Jennet Bierley, and Ellen Bierley accused by a 14-year-old girl, Grace Sowerbutts, of practising witchcraft. Their trial at Lancaster Assizes in England on 19 August 1612 was one in a series of...

and others, in a series of trials that have become known as the Lancashire witch trials. One was tried at York

York

York is a walled city, situated at the confluence of the Rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. The city has a rich heritage and has provided the backdrop to major political events throughout much of its two millennia of existence...

Assizes on 27 July 1612, and another died in prison. Of the eleven individuals who went to trial—nine women and two men—ten were found guilty and executed by hanging; one was found not guilty.

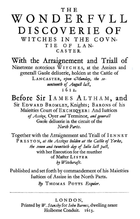

The trials were unusual for England at that time in two respects: the official publication of the proceedings by the clerk to the court, Thomas Potts, in his The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster

The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster

The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster is the account of a series of English witch trials that took place on 18–19 August 1612, commonly known as the Lancashire witch trials. Except for one trial held in York they took place at Lancaster Assizes...

, and in the number of witches hanged together: ten at Lancaster and one at York. It has been estimated that all of the English witch trials between the early 15th and early 18th centuries resulted in fewer than 500 executions, so this series of trials during the summer of 1612 accounts for more than 2 per cent of that total.

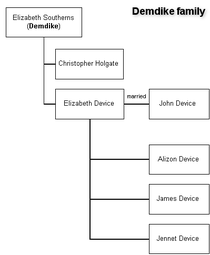

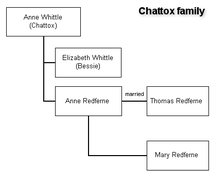

Six of the Pendle witches came from one of two families, each headed by a female in her eighties at the time of the trials: Elizabeth Southerns (aka Demdike ), her daughter Elizabeth Device, and her grandchildren James and Alizon Device; Anne Whittle (aka Chattox), and her daughter Anne Redferne. The others accused were Jane Bulcock and her son John Bulcock, Alice Nutter, Katherine Hewitt, Alice Gray, and Jennet Preston. The outbreaks of witchcraft in and around Pendle may demonstrate the extent to which people could make a living by posing as witches. Many of the allegations resulted from accusations that members of the Demdike and Chattox families made against each other, perhaps because they were in competition, both trying to make a living from healing, begging, and extortion.

Religious and political background

Pendle Hill

Pendle Hill is located in the north-east of Lancashire, England, near the towns of Burnley, Nelson, Colne, Clitheroe and Padiham, an area known as Pendleside. Its summit is above mean sea level. It gives its name to the Borough of Pendle. It is an isolated hill, separated from the Pennines to the...

in Lancashire

Lancashire

Lancashire is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in the North West of England. It takes its name from the city of Lancaster, and is sometimes known as the County of Lancaster. Although Lancaster is still considered to be the county town, Lancashire County Council is based in Preston...

, a county which, at the end of the 16th century, was regarded by the authorities as a wild and lawless region: an area "fabled for its theft, violence and sexual laxity, where the church was honoured without much understanding of its doctrines by the common people". The nearby Cistercian abbey at Whalley

Whalley Abbey

Whalley Abbey is a former Cistercian abbey in Whalley, Lancashire, England. After the dissolution of the monasteries, the abbey was largely demolished and a country house was built on the site. In the 20th century the house was modified and it is now the Retreat and Conference House of the...

had been dissolved

Dissolution of the Monasteries

The Dissolution of the Monasteries, sometimes referred to as the Suppression of the Monasteries, was the set of administrative and legal processes between 1536 and 1541 by which Henry VIII disbanded monasteries, priories, convents and friaries in England, Wales and Ireland; appropriated their...

by Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

in 1537, a move strongly resisted by the local people, over whose lives the abbey had until then exerted a powerful influence. Despite the abbey's closure, and the execution of its abbot, the people of Pendle remained largely faithful to their Roman Catholic beliefs and were quick to revert to Catholicism on Queen Mary's

Mary I of England

Mary I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from July 1553 until her death.She was the only surviving child born of the ill-fated marriage of Henry VIII and his first wife Catherine of Aragon. Her younger half-brother, Edward VI, succeeded Henry in 1547...

accession to the throne in 1553. When Mary's Protestant half-sister Elizabeth

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

came to the throne in 1558, Catholic priests once again had to go into hiding but in remote areas like Pendle they continued to celebrate mass

Mass (liturgy)

"Mass" is one of the names by which the sacrament of the Eucharist is called in the Roman Catholic Church: others are "Eucharist", the "Lord's Supper", the "Breaking of Bread", the "Eucharistic assembly ", the "memorial of the Lord's Passion and Resurrection", the "Holy Sacrifice", the "Holy and...

in secret.

On Elizabeth's death in 1603 she was succeeded by James I

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

. Strongly influenced by Scotland's separation from the Catholic Church during the Scottish Reformation

Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was Scotland's formal break with the Papacy in 1560, and the events surrounding this. It was part of the wider European Protestant Reformation; and in Scotland's case culminated ecclesiastically in the re-establishment of the church along Reformed lines, and politically in...

, James was intensely interested in Protestant theology, focusing much of his curiosity on the theology of witchcraft. By the early 1590s, he had become convinced that he was being plotted against by Scottish witches. After a visit to Denmark, he had attended the trial in 1590 of the North Berwick Witches

North Berwick witch trials

The North Berwick witch trials were the trials in 1590 of a number of people from East Lothian, Scotland, accused of witchcraft in the St Andrew's Auld Kirk in North Berwick. They ran for two years and implicated seventy people. The accused included Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell on charges...

, who were convicted of using witchcraft to send a storm against the ship that carried James and his wife Anne

Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark was queen consort of Scotland, England, and Ireland as the wife of King James VI and I.The second daughter of King Frederick II of Denmark, Anne married James in 1589 at the age of fourteen and bore him three children who survived infancy, including the future Charles I...

back to Scotland. In 1597, he wrote a book, Daemonologie

Daemonologie

Daemonologie is the book written and published in 1597 by King James VI of Scotland . In the book he approves and supports the practise of witch hunting...

, instructing his followers that they must denounce and prosecute any supporters or practitioners of witchcraft. One year after James acceded to the English throne, a law was enacted imposing the death penalty in cases where it was proven that harm had been caused through the use of magic, or corpses had been exhumed for magical purposes. James was, however, sceptical of the evidence presented in witch trials, even to the extent of personally exposing discrepancies in the testimonies presented against some accused witches.

In early 1612, the year of the trials, every justice of the peace

Justice of the Peace

A justice of the peace is a puisne judicial officer elected or appointed by means of a commission to keep the peace. Depending on the jurisdiction, they might dispense summary justice or merely deal with local administrative applications in common law jurisdictions...

(JP) in Lancashire was ordered to compile a list of recusants in their area, i.e. those who refused to attend the English Church and to take communion

Eucharist

The Eucharist , also called Holy Communion, the Sacrament of the Altar, the Blessed Sacrament, the Lord's Supper, and other names, is a Christian sacrament or ordinance...

, a criminal offence at that time. Roger Nowell of Read Hall

Read Hall and Park

Read Hall and Park is a Manor House and ornamental grounds of about in Read, Lancashire, England. The Hall dates from the early 18th century and is a grade II* listed building. Neither are open to the public.-Location:...

, on the edge of Pendle Forest, was the JP for Pendle. It was against this background of seeking out religious nonconformists that, in March 1612, Nowell investigated a complaint made to him by the family of John Law, a pedlar

Peddler

A peddler, in British English pedlar, also known as a canvasser, cheapjack, monger, or solicitor , is a travelling vendor of goods. In England, the term was mostly used for travellers hawking goods in the countryside to small towns and villages; they might also be called tinkers or gypsies...

, who claimed to have been injured by witchcraft. Many of those who subsequently became implicated as the investigation progressed did indeed consider themselves to be witches, in the sense of being village healers who practised magic, probably in return for payment, but such men and women were common in 16th-century rural England, an accepted part of village life.

It was perhaps difficult for the judges charged with hearing the trials—Sir James Altham and Sir Edward Bromley—to understand King James's attitude towards witchcraft. The king was head of the judiciary, and Bromley was hoping for promotion to a circuit nearer London. Altham was nearing the end of his judicial career, but he had recently been accused of a miscarriage of justice at the York Assizes, which had resulted in a woman being sentenced to death by hanging for witchcraft. The judges may have been uncertain whether the best way to gain the king's favour was by encouraging convictions, or by "sceptically testing the witnesses to destruction".

Events leading up to the trials

On her way to Trawden Forest

Trawden Forest

Trawden Forest is a civil parish in the English county of Lancashire.Trawden Forest forms part of the borough of Pendle; its main community is Trawden formerly called Beardshaw....

Alizon Device encountered John Law, a pedlar from Halifax

Halifax, West Yorkshire

Halifax is a minster town, within the Metropolitan Borough of Calderdale in West Yorkshire, England. It has an urban area population of 82,056 in the 2001 Census. It is well-known as a centre of England's woollen manufacture from the 15th century onward, originally dealing through the Halifax Piece...

, and asked him for some pins. Seventeenth-century metal pins were hand-made and relatively expensive, but they were frequently needed for magical purposes, such as in healing – particularly for treating warts – divination, and for love magic

Love magic

Love magic is the attempt to bind the passions of another, or to capture them as a sex object through magical means rather than through direct activity. It can be implemented in a variety of ways, such as written spells, dolls, charms, amulets, love potions, or different rituals.Love magic has...

, which may have been why Alizon was so keen to get hold of them and why Law was so reluctant to sell them to her. Whether she meant to buy them, as she claimed, and Law refused to undo his pack for such a small transaction, or whether she had no money and was begging for them, as Law's son Abraham claimed, is unclear. A few minutes after their encounter Alizon saw Law stumble and fall, perhaps because he suffered a stroke; he managed to regain his feet and reach a nearby inn. Initially Law made no accusations against Alizon, but she appears to have been convinced of her own powers; when Abraham Law took her to visit his father a few days after the incident, she reportedly confessed and asked for his forgiveness.

Alizon Device, her mother Elizabeth, and her brother James were summoned to appear before Nowell on 30 March 1612. Alizon confessed that she had sold her soul to the Devil, and that she had told him to lame John Law after he had called her a thief. Her brother, James, stated that his sister had also confessed to bewitching a local child. Elizabeth was more reticent, admitting only that her mother, Demdike, had a mark on her body, something that many, including Nowell, would have regarded as having been left by the Devil after he had sucked her blood. When questioned about Anne Whittle (Chattox), the matriarch of the other family reputedly involved in witchcraft in and around Pendle, Alizon perhaps saw an opportunity for revenge. There may have been bad blood between the two families, possibly dating from 1601, when a member of Chattox's family broke into Malkin Tower, the home of the Devices, and stole goods worth about £1, equivalent to about £100 as of 2008. Alizon accused Chattox of murdering four men by witchcraft, and of killing her father, John Device, who had died in 1601. She claimed that her father had been so frightened of Old Chattox that he had agreed to give her 8 pounds (3.6 kg) of oatmeal each year in return for her promise not to hurt his family. The meal was handed over annually until the year before John's death; on his deathbed John claimed that his sickness had been caused by Chattox because they had not paid for protection.

On 2 April 1612, Demdike, Chattox, and Chattox's daughter Anne Redferne, were summoned to appear before Nowell. Both Demdike and Chattox were by then blind and in their eighties, and both provided Nowell with damaging confessions. Demdike claimed that she had given her soul to the Devil 20 years previously, and Chattox that she had given her soul to "a Thing like a Christian man", on his promise that "she would not lack anything and would get any revenge she desired". Although Anne Redferne made no confession, Demdike said that she had seen her making clay figures. Margaret Crooke, another witness seen by Nowell that day, claimed that her brother had fallen sick and died after having had a disagreement with Redferne, and that he had frequently blamed her for his illness. Based on the evidence and confessions he had obtained, Nowell committed Demdike, Chattox, Anne Redferne and Alizon Device to Lancaster Gaol, to be tried for maleficium

Maleficium (sorcery)

Maleficium is a Latin term meaning "wrongdoing" or "mischief" and is used to describe malevolent, dangerous, or harmful magic, "evildoing" or "malevolent sorcery"...

—causing harm by witchcraft—at the next assizes.

Meeting at Malkin Tower

The committal and subsequent trial of the four women might have been the end of the matter, had it not been for a meeting organised by Elizabeth Device at Malkin Tower, the home of the Demdikes, held on 6 April 1612, Good FridayGood Friday

Good Friday , is a religious holiday observed primarily by Christians commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus Christ and his death at Calvary. The holiday is observed during Holy Week as part of the Paschal Triduum on the Friday preceding Easter Sunday, and may coincide with the Jewish observance of...

. To feed the party, James Device stole a neighbour's sheep.

Friends and others sympathetic to the family attended, and when word of it reached Roger Nowell, he decided to investigate. On 27 April 1612, an inquiry was held before Nowell and another magistrate, Nicholas Bannister, to determine the purpose of the meeting at Malkin Tower, who had attended, and what had happened there. As a result of the inquiry, eight more people were accused of witchcraft and committed for trial: Elizabeth Device, James Device, Alice Nutter, Katherine Hewitt, John Bulcock, Jane Bulcock, Alice Gray and Jennet Preston. Preston lived across the border in Yorkshire, so she was sent for trial at York Assizes; the others were sent to Lancaster Gaol, to join the four already imprisoned there.

Malkin Tower is believed to have been near the village of Newchurch in Pendle

Newchurch in Pendle

Newchurch in Pendle is a village in Lancashire adjacent to Barley, at the foot of Pendle Hill. Famous for the Demdike family of Pendle witches who lived there in the 17th century. Newchurch used to be called 'Goldshaw Booth' and later 'Newchurch in Pendle Forest', however this was shortened to...

, on the site of present-day Malkin Tower Farm, and to have been demolished soon after the trials.

Trials

The Pendle witches were tried in a group that also included the Samlesbury witchesSamlesbury witches

The Samlesbury witches were three women from the Lancashire village of Samlesbury Jane Southworth, Jennet Bierley, and Ellen Bierley accused by a 14-year-old girl, Grace Sowerbutts, of practising witchcraft. Their trial at Lancaster Assizes in England on 19 August 1612 was one in a series of...

, Jane Southworth, Jennet Brierley, and Ellen Brierley, the charges against whom included child murder and cannibalism; Margaret Pearson, the so-called Padiham

Padiham

Padiham is a small town and civil parish on the River Calder, about west of Burnley and south of Pendle Hill, in Lancashire, England. It is part of the Borough of Burnley but also has its own town council with varied powers.-History:...

witch, who was facing her third trial for witchcraft, this time for killing a horse; and Isobel Robey from Windle

Windle, Merseyside

Windle is a suburb of St. Helens, and Ward of the metropolitan borough of the same name. The 2001 census gives Windle a population of 8,621 in 3,607 households. It borders the villages of Eccleston and Rainford. It was one of the original four townships alongside Eccleston, Parr and Sutton formed...

, accused of using witchcraft to cause sickness.

Some of the accused Pendle witches, such as Alizon Device, seem to have genuinely believed in their guilt. Others protested their innocence to the end. Jennet Preston was the first to be tried, at York Assizes on 27 July 1612, where she was found guilty and subsequently hanged. Nine others—Alizon Device, Elizabeth Device, James Device, Anne Whittle, Anne Redferne, Alice Nutter, Katherine Hewitt, John Bulcock and Jane Bulcock—were found guilty and hanged at Gallows Hill in Lancaster on 20 August 1612. Elizabeth Southerns died while awaiting trial. Only one of the accused, Alice Grey, was found not guilty.

York Assizes, 27 July 1612

Jennet Preston lived in GisburnGisburn

Gisburn is a village, civil parish and ward within the Ribble Valley borough of Lancashire, England. It lies northeast of Clitheroe. The parish of Gisburn had a population of 506, and the ward had 1287, recorded in the 2001 census....

, which was then in Yorkshire

Yorkshire

Yorkshire is a historic county of northern England and the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its great size in comparison to other English counties, functions have been increasingly undertaken over time by its subdivisions, which have also been subject to periodic reform...

, so she was sent to York Assizes for trial. Her judges were Sir James Altham and Sir Edward Bromley. Preston was accused of murdering Thomas Lister by witchcraft, to which she pleaded not guilty. She had already appeared before Bromley in 1611, charged with murdering a child by witchcraft, but had been found not guilty. The most damning evidence given against her was that when she had been taken to see Lister's body, the corpse "bled fresh bloud presently, in the presence of all that were there present" after she touched it. According to a statement made to Nowell by James Device on 27 April, Jennet had attended the Malkin Tower meeting to seek help with Lister's murder. She was found guilty, and sentenced to death by hanging

Hanging

Hanging is the lethal suspension of a person by a ligature. The Oxford English Dictionary states that hanging in this sense is "specifically to put to death by suspension by the neck", though it formerly also referred to crucifixion and death by impalement in which the body would remain...

.

Lancaster Assizes, 18–19 August 1612

18 August

Anne Whittle (Chattox) was accused of the murder of Robert Nutter. She pleaded not guilty, but the confession she had made to Roger Nowell was read out in court, and evidence against her was presented by James Robinson, who had lived with the Chattox family 20 years earlier. He claimed to remember that Nutter had accused Chattox of turning his beer sour, and that she was commonly believed to be a witch. Chattox broke down and admitted her guilt, calling on God for forgiveness and the judges to be merciful to her daughter, Anne Redferne.

Elizabeth Device was charged with the murders of James Robinson, John Robinson and, together with Alice Nutter and Demdike, the murder of Henry Mitton. Potts records that "this odious witch" suffered from a facial deformity resulting in her left eye being set lower than her right. The main witness against Device was her daughter, Jennet, who was about nine years old. When Jennet was asked to stand up and give evidence against her mother, Elizabeth began to scream and curse her daughter, forcing the judges to have her removed from the courtroom before the evidence could be heard. Jennet was placed on a table and stated that she believed her mother had been a witch for three or four years. She also said her mother had a familiar

Familiar spirit

In European folklore and folk-belief of the Medieval and Early Modern periods, familiar spirits were supernatural entities believed to assist witches and cunning folk in their practice of magic...

called Ball, who appeared in the shape of a brown dog. Jennet claimed to have witnessed conversations between Ball and her mother, in which Ball had been asked to help with various murders. James Device also gave evidence against his mother, saying he had seen her making a clay figure of one of her victims, John Robinson. Elizabeth Device was found guilty.

James Device pleaded not guilty to the murders by witchcraft of Anne Townley and John Duckworth. However he, like Chattox, had earlier made a confession to Nowell, which was read out in court. That, and the evidence presented against him by his sister Jennet, who said that she had seen her brother asking a black dog he had conjured up to help him kill Townley, was sufficient to persuade the jury to find him guilty.

19 August

The trials of the three Samlesbury witches

Samlesbury witches

The Samlesbury witches were three women from the Lancashire village of Samlesbury Jane Southworth, Jennet Bierley, and Ellen Bierley accused by a 14-year-old girl, Grace Sowerbutts, of practising witchcraft. Their trial at Lancaster Assizes in England on 19 August 1612 was one in a series of...

were heard before Anne Redferne's first appearance in court, late in the afternoon, charged with the murder of Robert Nutter. The evidence against her was considered unsatisfactory, and she was acquitted.

Anne Redferne was not so fortunate the following day, when she faced her second trial, for the murder of Robert Nutter's father, Christopher, to which she pleaded not guilty. Demdikes's statement to Nowell, which accused Anne of having made clay figures of the Nutter family, was read out in court. Witnesses were called to testify that Anne was a witch "more dangerous than her Mother". However, she refused to admit her guilt to the end, and had given no evidence against any others of the accused. Anne Redferne was found guilty.

Jane Bulcock and her son John Bulcock, both from Newchurch in Pendle

Newchurch in Pendle

Newchurch in Pendle is a village in Lancashire adjacent to Barley, at the foot of Pendle Hill. Famous for the Demdike family of Pendle witches who lived there in the 17th century. Newchurch used to be called 'Goldshaw Booth' and later 'Newchurch in Pendle Forest', however this was shortened to...

, were accused and found guilty of the murder by witchcraft of Jennet Deane. Both denied that they had attended the meeting at Malkin Tower, but Jennet Device identified Jane as having been one of those present, and John as having turned the spit to roast the stolen sheep, the centrepiece of the Good Friday meeting at the Demdike's home.

Alice Nutter was unusual among the accused in being comparatively wealthy, the widow of a tenant yeoman farmer. She made no statement either before or during her trial, except to enter her plea of not guilty to the charge of murdering Henry Mitton by witchcraft. The prosecution alleged that she, together with Demdike and Elizabeth Device, had caused Mitton's death after he had refused to give Demdike a penny she had begged from him. The only evidence against Alice seems to have been that James Device claimed Demdike had told him of the murder, and Jennet Device in her statement said that Alice had been present at the Malkin Tower meeting. Alice may have called in on the meeting at Malkin Tower on her way to a secret (and illegal) Good Friday Catholic service, and refused to speak for fear of incriminating her fellow Catholics. Many of the Nutter family were Catholics, and two had been executed as Jesuit

Society of Jesus

The Society of Jesus is a Catholic male religious order that follows the teachings of the Catholic Church. The members are called Jesuits, and are also known colloquially as "God's Army" and as "The Company," these being references to founder Ignatius of Loyola's military background and a...

priests, one in 1584 and the other in 1600. Alice Nutter was found guilty.

Katherine Hewitt (aka Mould-Heeles) was charged and found guilty of the murder of Anne Foulds. She was the wife of a clothier from Colne

Colne

Colne is the second largest town and civil parish in the Borough of Pendle in Lancashire, England, with a population of 20,118. It lies at the eastern end of the M65, 6 miles north-east of Burnley, with Nelson immediately adjacent, in the Aire Gap with two main roads leading into the Yorkshire...

, and had attended the meeting at Malkin Tower with Alice Grey. According to the evidence given by James Device, both Hewitt and Grey told the others at that meeting that they had killed a child from Colne, Anne Foulds. Jennet Device also picked Katherine out of a line-up, and confirmed her attendance at the Malkin Tower meeting.

Alice Gray was accused with Katherine Hewitt of the murder of Anne Foulds. Potts does not provide an account of Alice Gray's trial, simply recording her as one of the Samlesbury witches – which she was not, as she was one of those identified as having been at the Malkin Tower meeting – and naming her in the list of those found not guilty.

Alizon Device, whose encounter with John Law had triggered the events leading up to the trials, was charged with causing harm by witchcraft. Uniquely among the accused, Alizon was confronted in court by her alleged victim, John Law. She seems to have genuinely believed in her own guilt; when Law was brought into court Alizon fell to her knees in tears and confessed. She was found guilty.

The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster

Although written as an apparently verbatim account, The Wonderfull Discoverie is not a report of what was actually said at the trial but is instead reflecting what happened. Nevertheless, Potts "seems to give a generally trustworthy, although not comprehensive, account of an Assize witchcraft trial, provided that the reader is constantly aware of his use of written material instead of verbatim reports".

The trials took place not quite seven years after the Gunpowder Plot

Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was a failed assassination attempt against King James I of England and VI of Scotland by a group of provincial English Catholics led by Robert Catesby.The plan was to blow up the House of...

to blow up the Houses of Parliament in an attempt to kill King James and the Protestant aristocracy had been foiled. It was alleged that the Pendle witches had hatched their own gunpowder plot to blow up Lancaster Castle, although historian Stephen Pumfrey has suggested that the "preposterous scheme" was invented by the examining magistrates and simply agreed to by James Device in his witness statement. It may therefore be significant that Potts dedicated The Wonderfull Discoverie to Thomas Knyvet

Thomas Knyvet, 1st Baron Knyvet

Thomas James Knyvet, 1st Baron Knyvet was the second son of Sir Henry Knyvet of Charlton, Wiltshire and Anne Pickering, daughter of Sir Christopher Pickering of Killington, Westmoreland. His half-sister Catherine Knyvet was married to Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk...

and his wife Elizabeth; Knyvet was the man credited with apprehending Guy Fawkes

Guy Fawkes

Guy Fawkes , also known as Guido Fawkes, the name he adopted while fighting for the Spanish in the Low Countries, belonged to a group of provincial English Catholics who planned the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605.Fawkes was born and educated in York...

and thus saving the king.

Modern interpretation

It has been estimated that all of the English witch trials between the early 15th and early 18th centuries resulted in fewer than 500 executions, so this one series of trials during the summer of 1612 accounts for more than 2 percent of that total. Court records show that Lancashire was unusual in the north of England for the frequency of its witch trials. Neighbouring CheshireCheshire

Cheshire is a ceremonial county in North West England. Cheshire's county town is the city of Chester, although its largest town is Warrington. Other major towns include Widnes, Congleton, Crewe, Ellesmere Port, Runcorn, Macclesfield, Winsford, Northwich, and Wilmslow...

, for instance, also suffered from economic problems and religious activists, but there only 47 individuals were indicted for causing harm by witchcraft between 1589 and 1675, of whom 11 were found guilty.

Pendle was part of the parish of Whalley

Whalley, Lancashire

Whalley is a large village in the Ribble Valley on the banks of the River Calder in Lancashire, England. It is overlooked by Whalley Nab, a large picturesque wooded hill over the river from the village....

, an area covering 180 square miles (466.2 km²), too large to be effective in preaching and teaching the doctrines of the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

: both the survival of Catholicism and the upsurge of witchcraft in Lancashire have been attributed to its over-stretched parochial structure. Until its dissolution

Dissolution of the Monasteries

The Dissolution of the Monasteries, sometimes referred to as the Suppression of the Monasteries, was the set of administrative and legal processes between 1536 and 1541 by which Henry VIII disbanded monasteries, priories, convents and friaries in England, Wales and Ireland; appropriated their...

, the spiritual needs of the people of Pendle and surrounding districts had been served by nearby Whalley Abbey

Whalley Abbey

Whalley Abbey is a former Cistercian abbey in Whalley, Lancashire, England. After the dissolution of the monasteries, the abbey was largely demolished and a country house was built on the site. In the 20th century the house was modified and it is now the Retreat and Conference House of the...

, but its closure in 1537 left a moral vacuum.

Many of the allegations made in the Pendle witch trials resulted from members of the Demdike and Chattox families making accusations against each other. Historian John Swain has said that the outbreaks of witchcraft in and around Pendle demonstrate the extent to which people could make a living either by posing as a witch, or by accusing or threatening to accuse others of being a witch. Although it is implicit in much of the literature on witchcraft that the accused were victims, often mentally or physically abnormal, for some at least, it may have been a trade like any other, albeit one with significant risks. There may have been bad blood between the Demdike and Chattox families because they were in competition with each other, trying to make a living from healing, begging, and extortion. The Demdikes are believed to have lived close to Newchurch in Pendle, and the Chattox family about 2 miles (3.2 km) away, near the village of Fence

Fence, Lancashire

Fence is a village in Pendle, Lancashire close to the towns of Nelson and Burnley. It lies alongside the A6068 road, known locally as the Padiham bypass...

.

Aftermath and legacy

Altham continued with his judicial career until his death in 1617, and Bromley achieved his desired promotion to the Midlands Circuit in 1616. Potts was given the keepership of Skalme Park by James in 1615, to breed and train the king's hounds. In 1618, he was given responsibility for "collecting the forfeitures on the laws concerning sewers, for twenty-one years". Having played her part in the deaths of her mother, brother, and sister, Jennet Device may eventually have found herself accused of witchcraft. A woman with that name was listed in a group of 20 tried at Lancaster Assizes on 24 March 1634, although it cannot be certain that it was the same Jennet Device. The charge against her was the murder of Isabel Nutter, William Nutter's wife. In that series of trials the chief prosecution witness was a ten-year-old boy, Edmund Robinson. All but one of the accused were found guilty, but the judges refused to pass death sentences, deciding instead to refer the case to the king, Charles ICharles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

. Under cross-examination in London, Robinson admitted that he had fabricated his evidence, but even though four of the accused were eventually pardoned, they all remained incarcerated in Lancaster Gaol, where it is likely that they died. An official record dated 22 August 1636 lists Jennet Device as one of those still held in the prison.

These later Lancashire witchcraft trials were the subject of a contemporary play written by Thomas Heywood and Richard Brome, The Late Lancashire Witches

The Late Lancashire Witches

The Late Lancashire Witches is a Caroline era stage play, written by Thomas Heywood and Richard Brome, published in 1634. The play is a topical melodrama on the subject of the witchcraft controversy that arose in Lancashire in 1633.-Performance:...

. More recently another play, Cold Light Singing, based on the story of the Pendle witches, has been touring the UK since 2004. The writer and poet Blake Morrison treated the subject—albeit in a modern context—in his suite of poems Pendle Witches, published in 1996.

William Harrison Ainsworth

William Harrison Ainsworth was an English historical novelist born in Manchester. He trained as a lawyer, but the legal profession held no attraction for him. While completing his legal studies in London he met the publisher John Ebers, at that time manager of the King's Theatre, Haymarket...

, a Victorian

Victorian era

The Victorian era of British history was the period of Queen Victoria's reign from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. It was a long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence...

novelist considered in his day the equal of Dickens

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens was an English novelist, generally considered the greatest of the Victorian period. Dickens enjoyed a wider popularity and fame than had any previous author during his lifetime, and he remains popular, having been responsible for some of English literature's most iconic...

, wrote a romanticised account of the Pendle witches published in 1849. The Lancashire Witches

The Lancashire Witches (novel)

The Lancashire Witches is the only one of William Harrison Ainsworth's 40 novels that has remained continuously in print since its first publication. It was serialised in the Sunday Times newspaper in 1848; a book edition appeared the following year, published by Henry Colburn...

is the only one of his 40 novels never to have been out of print

Out of print

Out of print refers to an item, typically a book , but can include any print or visual media or sound recording, that is in the state of no longer being published....

. Pendle Hill

Pendle Hill

Pendle Hill is located in the north-east of Lancashire, England, near the towns of Burnley, Nelson, Colne, Clitheroe and Padiham, an area known as Pendleside. Its summit is above mean sea level. It gives its name to the Borough of Pendle. It is an isolated hill, separated from the Pennines to the...

, which dominates the landscape of the area, continues to be associated with witchcraft, and hosts a hilltop gathering every Halloween

Halloween

Hallowe'en , also known as Halloween or All Hallows' Eve, is a yearly holiday observed around the world on October 31, the night before All Saints' Day...

. In 2004, the television show Most Haunted

Most Haunted

Most Haunted is a British paranormal documentary reality television series. The series was first shown on 25 May 2002 and ended on 21 July 2010. It was broadcast on Living and presented by Yvette Fielding. The programme was based on investigating purported paranormal activity...

produced a Halloween Special on the Pendle witches and the hauntings surrounding Pendle Hill. The British writer, Robert Neill

Robert Neill (British writer of historical fiction)

Robert Neill was a British writer of historical fiction. He was born in Manchester, southern Lancashire in the northwest of England, the setting for his best known work, Mist over Pendle, a novelisation of the 1612 witchcraft trials in Pendle, Lancashire. He was educated at Lytham and Cambridge,...

, dramatised the events of 1612 in his novel Mist over Pendle, first published in 1951.

In modern times the witches have become the inspiration for Pendle's tourism and heritage industries, with local shops selling a variety of witch-motif gifts. Moorhouse's

Moorhouse's Brewery

Moorhouse's is an independent brewery founded in 1865 by William Moorhouse in Burnley in Lancashire, UK as a producer of mineral waters and low alcohol beers known as hop bitters. It first produced cask ales in 1978.-History:...

produces a beer called Pendle Witches Brew, and there is a Pendle Witch Trail running from Pendle Heritage Centre to Lancaster Castle, where the accused witches were held before their trial. The X43/X44 bus route run by Burnley & Pendle

Burnley & Pendle

Transdev Burnley & Pendle is a bus operator running within the boroughs of Burnley and Pendle, and into the surrounding areas including Accrington, Keighley and the high profile express service to Manchester...

has been branded The Witch Way

The Witch Way

The Witch Way is the current name for the long-standing bus route X43, which runs between Manchester and Nelson, England. The service is currently operated by Transdev Burnley & Pendle.The route has operated continuously since 1948...

, with some of the vehicles operating on it named after the witches in the trial.

A petition was presented to UK Home Secretary

Home Secretary

The Secretary of State for the Home Department, commonly known as the Home Secretary, is the minister in charge of the Home Office of the United Kingdom, and one of the country's four Great Offices of State...

Jack Straw

Jack Straw

Jack Straw , British politician.Jack Straw may also refer to:* Jack Straw , English* "Jack Straw" , 1971 song by the Grateful Dead* Jack Straw by W...

in 1998 asking for the witches to be pardoned, but it was decided that their convictions should stand. Ten years later, in 2008, another petition was organised in an attempt to obtain pardons for Chattox and Demdike. It followed the Swiss government's pardon earlier that year of Anna Göldi

Anna Göldi

Anna Göldi Anna Göldi Anna Göldi (also Anna Göldin, October 24, 1734 – June 13, 1782 is known as the "last witch" in Switzerland. She was executed for murder in June 1782 in Glarus....

, beheaded in 1782, thought to be the last person in Europe to be executed as a witch.