Phylloxera

Encyclopedia

Greek language

Greek is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages. Native to the southern Balkans, it has the longest documented history of any Indo-European language, spanning 34 centuries of written records. Its writing system has been the Greek alphabet for the majority of its history;...

φύλλο, leaf, and ξερό, dry) is a pest of commercial grapevine

Vitis

Vitis is a genus of about 60 species of vining plants in the flowering plant family Vitaceae. The genus is made up of species predominantly from the Northern hemisphere. It is economically important as the source of grapes, both for direct consumption of the fruit and for fermentation to produce...

s worldwide, originally native to eastern North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

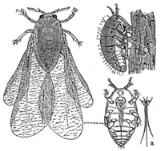

. These almost microscopic, pale yellow sap-sucking insect

Insect

Insects are a class of living creatures within the arthropods that have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body , three pairs of jointed legs, compound eyes, and two antennae...

s, related to aphid

Aphid

Aphids, also known as plant lice and in Britain and the Commonwealth as greenflies, blackflies or whiteflies, are small sap sucking insects, and members of the superfamily Aphidoidea. Aphids are among the most destructive insect pests on cultivated plants in temperate regions...

s, feed on the roots and leaves of grapevines depending on the phylloxera genetic strain. On Vitis vinifera L., the resulting deformations on roots ("nodosities" and "tuberosities") and secondary fungal infections can girdle roots, gradually cutting off the flow of nutrients and water to the vine. Nymphs

Nymph (biology)

In biology, a nymph is the immature form of some invertebrates, particularly insects, which undergoes gradual metamorphosis before reaching its adult stage. Unlike a typical larva, a nymph's overall form already resembles that of the adult. In addition, while a nymph moults it never enters a...

also form protective gall

Gall

Galls or cecidia are outgrowths on the surface of lifeforms caused by invasion by other lifeforms, such as parasites or bacterial infection. Plant galls are abnormal outgrowths of plant tissues and can be caused by various parasites, from fungi and bacteria, to insects and mites...

s on the undersides of grapevine leaves of some Vitis species and overwinter under the bark or on the vine roots; these leaf galls are typically only found on leaves of American vines.

Biology of Phylloxera

The phylloxera louse has a complex life-cycle of up to eighteen stages that is divisible into four principal forms: sexual form, leaf form, root form, and winged form.The sexual form begins with male and female eggs laid on the underside of young grape leaves. The male and female at this stage lack a digestive system, and once hatched, they mate and then die. Before the female dies, she lays one winter egg in the bark of the vine's trunk. This egg develops into the leaf form. This nymph, the fundatrix (stem mother), climbs onto a leaf and lays eggs (via parthenogenesis) into a leaf gall she creates by injecting saliva into the leaf. The nymphs that hatch from these eggs may move to other leaves, or move to the roots where they begin new infections in the root form. In this form they perforate the root to find nourishment, infecting the root with a poisonous secretion that prevents it from healing. It is this poison which eventually kills the vine. This nymph reproduces four to seven more generations of eggs (which are also capable of parthenogenetic reproduction) each summer. These offspring spread out to other roots of the vine, or to the roots of other vines through cracks in the soil. The generation of nymphs that hatch in the autumn hibernate in the roots and emerge the following spring when the sap begins to rise. In humid areas, the nymphs develop into the winged form (otherwise, they perform the same role without wings). These nymphs start the cycle over again by either remaining on the vine to lay male and female eggs on the bottom side of young grape leaves, or flying to an uninfected vine to do the same.

Many attempts have been made to interrupt this life cycle to eradicate phylloxera, but the louse has proven to be extremely adaptable, as no one stage of the life cycle is solely dependent upon another for the propagation of the species.

Fighting the "phylloxera plague"

In the late 19th century the phylloxera epidemic destroyed most of the vineyards for wineWine

Wine is an alcoholic beverage, made of fermented fruit juice, usually from grapes. The natural chemical balance of grapes lets them ferment without the addition of sugars, acids, enzymes, or other nutrients. Grape wine is produced by fermenting crushed grapes using various types of yeast. Yeast...

grape

Grape

A grape is a non-climacteric fruit, specifically a berry, that grows on the perennial and deciduous woody vines of the genus Vitis. Grapes can be eaten raw or they can be used for making jam, juice, jelly, vinegar, wine, grape seed extracts, raisins, molasses and grape seed oil. Grapes are also...

s in Europe, most notably in France

Great French Wine Blight

The Great French Wine Blight was a severe blight of the mid-19th century that destroyed many of the vineyards in France and laid to waste the wine industry...

. Phylloxera was introduced to Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

when avid botanists in Victorian England collected specimens of American vines in the 1850s. Because phylloxera is native to North America, the native grape species there are at least partially resistant. By contrast, the European wine grape Vitis vinifera

Vitis vinifera

Vitis vinifera is a species of Vitis, native to the Mediterranean region, central Europe, and southwestern Asia, from Morocco and Portugal north to southern Germany and east to northern Iran....

is very susceptible to the insect. The epidemic devastated vineyards in Britain and then moved to the mainland, destroying most of the European grape growing industry. In 1863, the first vines began to deteriorate inexplicably in the southern Rhône region of France. The problem spread rapidly across the continent. In France alone, total wine production fell from 84.5 million hectolitres in 1875 to only 23.4 million hectolitres in 1889. Some estimates hold that between two-thirds and nine-tenths of all European vineyards were destroyed.

In France, one of the desperate measures of grape growers was to bury a live toad

Toad

A toad is any of a number of species of amphibians in the order Anura characterized by dry, leathery skin , short legs, and snoat-like parotoid glands...

under each vine to draw out the "poison". Areas with soil

Soil

Soil is a natural body consisting of layers of mineral constituents of variable thicknesses, which differ from the parent materials in their morphological, physical, chemical, and mineralogical characteristics...

s composed principally of sand or schist

Schist

The schists constitute a group of medium-grade metamorphic rocks, chiefly notable for the preponderance of lamellar minerals such as micas, chlorite, talc, hornblende, graphite, and others. Quartz often occurs in drawn-out grains to such an extent that a particular form called quartz schist is...

were spared, and the spread was slowed in dry climates, but gradually the aphid spread across the continent. A significant amount of research was devoted to finding a solution to the phylloxera problem, and two major solutions gradually emerged: grafting cuttings onto resistant rootstocks

Rootstock

A rootstock is a plant, and sometimes just the stump, which already has an established, healthy root system, used for grafting a cutting or budding from another plant. The tree part being grafted onto the rootstock is usually called the scion...

and hybridization.

Use of a resistant, or tolerant, rootstock, developed by Charles Valentine Riley

Charles Valentine Riley

Charles Valentine Riley was a British-born American entomologist and artist.-Early Life:The son of a Church of England minister, Charles Valentine Riley was born on 19 September, 1843 in London’s Chelsea district. When he was around eleven his parents, the Rev. Charles and Mary Riley, chose to...

in collaboration with J. E. Planchon

Jules Émile Planchon

Jules Émile Planchon was a French botanist born in Ganges, Hérault.-Biography:After receiving his Doctorate of Science at the University of Montpellier in 1844, he worked for a while at the Royal Botanical Gardens in London, and for a few years was a teacher in Nancy and Ghent...

and promoted by T. V. Munson

Thomas Volney Munson

Thomas Volney Munson often referred to simply as T.V. Munson, was a horticulturist and breeder of grapes in Texas.-Background:...

, involved grafting a Vitis vinifera

Vitis vinifera

Vitis vinifera is a species of Vitis, native to the Mediterranean region, central Europe, and southwestern Asia, from Morocco and Portugal north to southern Germany and east to northern Iran....

scion

Grafting

Grafting is a horticultural technique whereby tissues from one plant are inserted into those of another so that the two sets of vascular tissues may join together. This vascular joining is called inosculation...

onto the roots of a resistant Vitis aestivalis

Vitis aestivalis

Vitis aestivalis is a species of grape native to eastern North America from southern Ontario east to Vermont, west to Oklahoma, and south to Florida and Texas. It is a vigorous vine, growing to 10 m or more high in trees...

or other American native species. This is the preferred method today, because the rootstock does not interfere with the development of the wine grapes, and it furthermore allows the customization of the rootstock to soil and weather conditions, as well as desired vigor. Unfortunately not all rootstocks are equally resistant. Between the 1960s and the 1980s in California

California

California is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area...

, many growers used a rootstock called AxR1. Even though it had already failed in many parts of the world by the early twentieth century, it was thought to be resistant by growers in California. Although phylloxera initially did not feed heavily on AxR1 roots, within twenty years, mutation and selective pressures within the phylloxera population began to overcome this rootstock, resulting in the eventual failure of most vineyards planted on AxR1. The replanting of afflicted vineyards continues today. Many have suggested that this failure was predictable, as one parent of AxR1 is in fact a susceptible V. vinifera cultivar. But the transmission of phylloxera tolerance is more complex, as is demonstrated by the continued success of 41B, an F1 hybrid

F1 hybrid

F1 hybrid is a term used in genetics and selective breeding. F1 stands for Filial 1, the first filial generation seeds/plants or animal offspring resulting from a cross mating of distinctly different parental types....

of Vitis berlandieri

Vitis berlandieri

Vitis berlandieri is a species of grape native to the southern North America, primarily Texas, New Mexico and Arkansas.It is primarily known for good tolerance against soils with a high content of lime, which can cause chlorosis in many vines of American origin...

and Vitis vinifera

Vitis vinifera

Vitis vinifera is a species of Vitis, native to the Mediterranean region, central Europe, and southwestern Asia, from Morocco and Portugal north to southern Germany and east to northern Iran....

. The full story of the planting of AxR1 in California, its recommendation, the warnings, financial consequences, and subsequent recriminations remains to be told. Modern phylloxera infestation also occurs when wineries are in need of fruit immediately, and choose to plant ungrafted vines rather than wait for grafted vines to be available.

The use of resistant American rootstock to guard against phylloxera also brought about a debate that remains unsettled to this day: whether self-rooted vines produce better wine than those that are grafted. Of course, the argument is essentially irrelevant wherever phylloxera exists. Had American rootstock not been available and used, there would be no V. vinifera wine industry in Europe or most places other than Chile, Washington State, and most of Australia. Cyprus avoided the phylloxera plague, and thus its wine stock has not been grafted for phylloxera resistant purposes.

By the end of the 19th Century, hybridization became a popular avenue of research for stopping the phylloxera louse. Hybridization is the breeding of Vitis vinifera

Vitis vinifera

Vitis vinifera is a species of Vitis, native to the Mediterranean region, central Europe, and southwestern Asia, from Morocco and Portugal north to southern Germany and east to northern Iran....

with resistant species. Most native American grapes are naturally phylloxera resistant (Vitis aestivalis

Vitis aestivalis

Vitis aestivalis is a species of grape native to eastern North America from southern Ontario east to Vermont, west to Oklahoma, and south to Florida and Texas. It is a vigorous vine, growing to 10 m or more high in trees...

, rupestris

Vitis rupestris

Vitis rupestris is a kind of grape native to the Southern and Western United States that is known by many common names including July, sand, sugar, beach, bush, currant, ingar, rock, and mountain grape. It is used for breeding several French-American hybrids as well as many root stocks. ...

, and riparia

Vitis riparia

Vitis riparia Michx, also commonly known as River Bank Grape or Frost Grape, is a native American climbing or trailing vine, widely distributed from Quebec to Texas, and Montana to New England. It is long-lived and capable of reaching into the upper canopy of the tallest trees...

are particularly so, while Vitis labrusca

Vitis labrusca

Vitis labrusca is a species of grapevines belonging to the Vitis genus in the flowering plant family Vitaceae. The vines are native to the eastern United States and are the source of many grape cultivars, including Catawba and Concord grapes, and many hybrid grape varieties such as Agawam,...

has a somewhat weak resistance to it) but have aromas that are off-putting to palates accustomed to European grapes. The intent of the cross was to generate a hybrid vine that was resistant to phylloxera but produced wine that did not taste like the American grape. Ironically, the hybrids tend not to be especially resistant to phylloxera, although they are much more hardy with respect to climate and other vine diseases. The new hybrid varieties have never gained the popularity of the traditional ones. In the EU they are generally banned or at least strongly discouraged from use in quality wine, although they are still in widespread use in much of North America, such as Missouri, Ontario, and upstate New York, where they yield commercially acceptable wines.

The only European grape that is natively resistant to phylloxera is the Assyrtiko

Assyrtiko

Assyrtiko or Asyrtiko is a white Greek wine grape indigenous to the island of Santorini. Assyrtiko is widely planted in the arid volcanic-ash-rich soil of Santorini and other Aegean islands, such as Paros...

grape which grows on the volcanic island of Santorini

Santorini (wine)

Santorini is a Greek wine region located on the archipelago of Santorini in the southern Cyclades islands of the Aegean Sea. Although wine has been produced there since ancient Greek times, when the region was known as Thíra, it was not until the Middle Ages that the wine of Santorini became famous...

, Greece, although it is not clear whether the resistance is due to the rootstock itself or the volcanic ash on which it grows.

To escape the threat of phylloxera, wines have been produced since 1979 on the sandy beaches of Provence’s Bouches-du-Rhône, which extends from the Gard Coast to the waterfront village of Saintes Maries de la Mer. The sand, sun and wind in this area has been a major deterrent to phylloxera. The wine produced here is called "Vins des Sables" or "wine of the sand".

External links

- Web page of the Phylloxera and Grape Industry Board of South Australia

- The Vine's Enemy: A profile of phylloxera drawn from the 2nd edition of The Oxford Companion to Wine