Polish cochineal

Encyclopedia

Polish cochineal also known as Polish carmine scales, is a scale insect

formerly used to produce a crimson

dye

of the same name, colloquially known as "Saint John's blood". The larva

e of P. polonica are sessile

parasites living on the roots of various herbs

—especially those of the perennial knawel—growing on the sandy soils of Central Europe

and other parts of Eurasia

. Before the development of aniline, alizarin

, and other synthetic dyes, the insect was of great economic importance, although its use was in decline after the introduction of Mexican

cochineal

to Europe in the 16th century.

In mid-July, the female Polish cochineal lays approximately 600-700 eggs, encased with a white waxy ootheca

In mid-July, the female Polish cochineal lays approximately 600-700 eggs, encased with a white waxy ootheca

, in the ground. When the larva

e hatch in late August or early September, they do not leave the egg case but remain inside until the end of winter. In late March or early April, the larvae emerge from the ground to feed for a short time on the low-growing leaves of the host plant before returning underground to feed on the plant's roots. At this point, the larvae undergo ecdysis

, shedding their exoskeleton

s together with their legs and antennae

, and they encyst by forming outer protective coatings (cysts) within the root tissues.

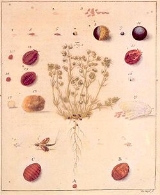

The cysts are small dark red or violet bubbles clustered on the host plant's roots. Female cysts are 3–4 mm (.12–16 in) in diameter. Males are half the size of their female counterparts and smaller in number, with only one male per 500 females. The cysts undergo ecdysis a number of times. When the male larva reaches the third-instar

developmental stage, it forms a delicate white cocoon and transforms into a pupa

in early June. In late June or early July, females, which are neotenous

and retain their larval form, re-emerge from the ground and slowly climb to the top of the host plant, where they wait until winged adult males, with characteristic plumes at the end of their abdomen

s, leave the cocoons and join them a few days later. Male imagines

(adult insects) do not feed and die shortly after mating

, while their female counterparts return underground to lay eggs. After oviposition

, the female insects shrink and die.

plants growing in sandy and arid, infertile soils. Its primary host

plant is the perennial knawel (Scleranthus perennis), but it has also been known to feed on plants of 20 other genera

, including mouse-ear hawkweed

(Hieracium pilosella), bladder campion

(Silene inflata), velvet bent

(Agrostis canina), Caragana

, smooth rupturewort

(Herniaria glabra), strawberry

(Fragaria), and cinquefoil (Potentilla

).

The insect was once commonly found throughout the Palearctic

and was recognised across Eurasia

, from France and England to China, but it was mainly in Central Europe

where it was common enough to make its industrial use economically viable. Excessive economic exploitation as well as the shrinking and degradation of its habitat have made the Polish cochineal a rare species. In 1994, it was included in the Ukrainian

Red Book of endangered species

. In Poland

, where it was still common in the 1960s, there is insufficient data to determine its conservation status, and no protective measures are in place.

developed a method of obtaining red dye from the larvae of the Polish cochineal. Despite the labor-intensive process of harvesting the cochineal and a relatively modest yield, the dye continued to be a highly sought-after commodity and a popular alternative to kermes

throughout the Middle Ages until it was superseded by Mexican

cochineal

in the 16th century.

Similar to other red dyes obtained from scale insects, the red coloring is derived from carminic acid

Similar to other red dyes obtained from scale insects, the red coloring is derived from carminic acid

with traces of kermesic acid. The Polish cochineal extract's natural carminic acid content is approximately 20%. The insects were harvested shortly before the female larvae reached maturity, i.e. in late June, usually around Saint John the Baptist's day

(June 24), hence the dye's folk name, Saint John's blood. The harvesting process involved uprooting the host plant and picking the female larvae, averaging approximately ten insects from each plant.

In Poland, including present-day Ukraine

, and elsewhere in Europe, plantations were operated in order to deal with the high toll on the host plants. The larvae were killed with boiling water or vinegar

and dried in the sun or in an oven, ground, and dissolved in sourdough

or in light rye beer called kvass

in order to remove fat. The extract could then be used for dyeing silk

, wool

, cotton

, or linen

. The dyeing process requires roughly 3-4 oz

of dye per pound

(180-250 g

per kilogram

) of silk and one pound of dye to color almost 20 pounds (50 g per kilogram) of wool.

Polish cochineal was widely traded in Europe during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance

Polish cochineal was widely traded in Europe during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance

. In the 15th and 16th centuries, along with grain, timber, and salt, it was one of Poland's and Lithuania

's chief exports, mainly to southern Germany

and northern Italy

as well as to France

, England

, the Ottoman Empire

, and Armenia

. In Poland, the cochineal trade was mostly monopolized by Jewish merchants, who bought the dye from peasants in Red Ruthenia

and other regions of Poland and Lithuania. The merchants shipped the dye to major Polish cities such as Kraków

, Gdańsk

(Danzig), and Poznań

. From there, the merchandise was exported to wholesalers in Breslau (Wrocław), Nuremberg

, Frankfurt

, Augsburg

, Venice

, and other destinations. The Polish cochineal trade was a lucrative business for the Jewish intermediaries; according to Marcin of Urzędów

(1595), one pound of Polish cochineal cost between four and five Venetian pounds. In terms of quantities, the trade reached its peak in the 1530s. In 1534, 1963 stones

(about 30 metric tons) of the dye were sold in Poznań alone.

The advent of cheaper Mexican cochineal

led to an abrupt slump in the Polish cochineal trade, and the 1540s saw a steep decline in quantities of the red dye exported from Poland. In 1547, Polish cochineal disappeared from the Poznań customs registry; a Volhynia

n clerk noted in 1566 that the dye no longer paid in Gdańsk. Perennial knawel plantations were replaced with cereal fields or pastures for raising cattle. Polish cochineal, which until then was mostly an export product, continued to be used locally by the peasants who collected it; it was employed not only for dyeing fabric but also as a vodka

colorant, an ingredient in folk medicine

, or even for decorative coloring of horses' tails.

With the partitions of Poland

at the end of the 18th century, vast markets in Russia

and Central Asia

opened to Polish cochineal, which became an export product again—this time, to the East. In the 19th century, Bukhara

, Uzbekistan

, became the principal Polish cochineal trading center in Central Asia; from there the dye was shipped to Kashgar

in Xinjiang

, and Kabul

and Herat

in Afghanistan

. It is possible that the Polish dye was used to manufacture some of the famous oriental rug

s.

The earliest known scientific study of the Polish cochineal is found in the (Polish Herbal

The earliest known scientific study of the Polish cochineal is found in the (Polish Herbal

) by Marcin of Urzędów

(1595), where it was described as "small red seeds" that grow under plant roots, becoming "ripe" in April and from which a little "bug" emerges in June. The first scientific comments by non-Polish authors were written by Segerius (1670) and von Bernitz (1672). In 1731, Johann Philipp Breyne

, wrote (translated into English during the same century), the first major treatise about the insect, including the results of his research on its physiology and life cycle. In 1934, Polish biologist Antoni Jakubski

wrote (Polish cochineal), a monograph taking into account both the insect's biology and historical role.

where the words for the color red and for the month of June both derive from the Proto-Slavic

(probably pronounced t͡ʃĭrwĭ), meaning "a worm" or "larva". (See examples in the table below.) In the Czech language

, as well as old Bulgarian

, this is true for both June and July, the two months when harvest of the insect's larvae was possible. In modern Polish

, is a word for June, as well as for the Polish cochineal () and its host plant, the perennial knawel ().

Scale insect

The scale insects are small insects of the order Hemiptera, generally classified as the superfamily Coccoidea. There are about 8,000 species of scale insects.-Ecology:...

formerly used to produce a crimson

Crimson

Crimson is a strong, bright, deep red color. It is originally the color of the dye produced from a scale insect, Kermes vermilio, but the name is now also used as a generic term for those slightly bluish-red colors that are between red and rose; besides crimson itself, these colors include...

dye

Dye

A dye is a colored substance that has an affinity to the substrate to which it is being applied. The dye is generally applied in an aqueous solution, and requires a mordant to improve the fastness of the dye on the fiber....

of the same name, colloquially known as "Saint John's blood". The larva

Larva

A larva is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle...

e of P. polonica are sessile

Sessility (zoology)

In zoology, sessility is a characteristic of animals which are not able to move about. They are usually permanently attached to a solid substrate of some kind, such as a part of a plant or dead tree trunk, a rock, or the hull of a ship in the case of barnacles. Corals lay down their own...

parasites living on the roots of various herbs

Herbaceous

A herbaceous plant is a plant that has leaves and stems that die down at the end of the growing season to the soil level. They have no persistent woody stem above ground...

—especially those of the perennial knawel—growing on the sandy soils of Central Europe

Central Europe

Central Europe or alternatively Middle Europe is a region of the European continent lying between the variously defined areas of Eastern and Western Europe...

and other parts of Eurasia

Eurasia

Eurasia is a continent or supercontinent comprising the traditional continents of Europe and Asia ; covering about 52,990,000 km2 or about 10.6% of the Earth's surface located primarily in the eastern and northern hemispheres...

. Before the development of aniline, alizarin

Alizarin

Alizarin or 1,2-dihydroxyanthraquinone is an organic compound with formula that has been used throughout history as a prominent dye, originally derived from the roots of plants of the madder genus.Alizarin was used as a red dye for the English parliamentary "new model" army...

, and other synthetic dyes, the insect was of great economic importance, although its use was in decline after the introduction of Mexican

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

cochineal

Cochineal

The cochineal is a scale insect in the suborder Sternorrhyncha, from which the crimson-colour dye carmine is derived. A primarily sessile parasite native to tropical and subtropical South America and Mexico, this insect lives on cacti from the genus Opuntia, feeding on plant moisture and...

to Europe in the 16th century.

Life cycle

Ootheca

An ootheca is a type of egg mass made by any member of a variety of species .The word is a latinized combination of oo-, meaning "egg", from the Greek word ōon , and theca, meaning a "cover" or "container", from the Greek theke...

, in the ground. When the larva

Larva

A larva is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle...

e hatch in late August or early September, they do not leave the egg case but remain inside until the end of winter. In late March or early April, the larvae emerge from the ground to feed for a short time on the low-growing leaves of the host plant before returning underground to feed on the plant's roots. At this point, the larvae undergo ecdysis

Ecdysis

Ecdysis is the moulting of the cuticula in many invertebrates. This process of moulting is the defining feature of the clade Ecdysozoa, comprising the arthropods, nematodes, velvet worms, horsehair worms, rotifers, tardigrades and Cephalorhyncha...

, shedding their exoskeleton

Exoskeleton

An exoskeleton is the external skeleton that supports and protects an animal's body, in contrast to the internal skeleton of, for example, a human. In popular usage, some of the larger kinds of exoskeletons are known as "shells". Examples of exoskeleton animals include insects such as grasshoppers...

s together with their legs and antennae

Antenna (biology)

Antennae in biology have historically been paired appendages used for sensing in arthropods. More recently, the term has also been applied to cilium structures present in most cell types of eukaryotes....

, and they encyst by forming outer protective coatings (cysts) within the root tissues.

The cysts are small dark red or violet bubbles clustered on the host plant's roots. Female cysts are 3–4 mm (.12–16 in) in diameter. Males are half the size of their female counterparts and smaller in number, with only one male per 500 females. The cysts undergo ecdysis a number of times. When the male larva reaches the third-instar

Instar

An instar is a developmental stage of arthropods, such as insects, between each molt , until sexual maturity is reached. Arthropods must shed the exoskeleton in order to grow or assume a new form. Differences between instars can often be seen in altered body proportions, colors, patterns, or...

developmental stage, it forms a delicate white cocoon and transforms into a pupa

Pupa

A pupa is the life stage of some insects undergoing transformation. The pupal stage is found only in holometabolous insects, those that undergo a complete metamorphosis, going through four life stages; embryo, larva, pupa and imago...

in early June. In late June or early July, females, which are neotenous

Neoteny

Neoteny , also called juvenilization , is one of the two ways by which paedomorphism can arise. Paedomorphism is the retention by adults of traits previously seen only in juveniles, and is a subject studied in the field of developmental biology. In neoteny, the physiological development of an...

and retain their larval form, re-emerge from the ground and slowly climb to the top of the host plant, where they wait until winged adult males, with characteristic plumes at the end of their abdomen

Abdomen

In vertebrates such as mammals the abdomen constitutes the part of the body between the thorax and pelvis. The region enclosed by the abdomen is termed the abdominal cavity...

s, leave the cocoons and join them a few days later. Male imagines

Imago

In biology, the imago is the last stage of development of an insect, after the last ecdysis of an incomplete metamorphosis, or after emergence from the pupa where the metamorphosis is complete...

(adult insects) do not feed and die shortly after mating

Mating

In biology, mating is the pairing of opposite-sex or hermaphroditic organisms for copulation. In social animals, it also includes the raising of their offspring. Copulation is the union of the sex organs of two sexually reproducing animals for insemination and subsequent internal fertilization...

, while their female counterparts return underground to lay eggs. After oviposition

Oviposition

Oviposition is the process of laying eggs by oviparous animals.Some arthropods, for example, lay their eggs with an organ called the ovipositor.Fish , amphibians, reptiles, birds and monetremata also lay eggs....

, the female insects shrink and die.

Host plants and geographic distribution

The Polish cochineal lives on herbaceousHerbaceous

A herbaceous plant is a plant that has leaves and stems that die down at the end of the growing season to the soil level. They have no persistent woody stem above ground...

plants growing in sandy and arid, infertile soils. Its primary host

Host (biology)

In biology, a host is an organism that harbors a parasite, or a mutual or commensal symbiont, typically providing nourishment and shelter. In botany, a host plant is one that supplies food resources and substrate for certain insects or other fauna...

plant is the perennial knawel (Scleranthus perennis), but it has also been known to feed on plants of 20 other genera

Genus

In biology, a genus is a low-level taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms, which is an example of definition by genus and differentia...

, including mouse-ear hawkweed

Mouse-ear Hawkweed

Mouse-ear Hawkweed is a yellow-flowered species of Asteraceae, native to Europe and northern Asia. It produces single, citrus-colored inflorescences. It is an allelopathic plant...

(Hieracium pilosella), bladder campion

Silene vulgaris

Silene vulgaris, Silene cucubalus or Bladder Campion is a plant species of the genus Silene of the Pink Family . It is native to Europe, where in some parts it is eaten, but is widespread in North America where it is considered a weed..-Gastronomy:In Spain, the young shoots and the leaves are used...

(Silene inflata), velvet bent

Agrostis

Agrostis is a genus of over 100 species belonging to the grass family Poaceae, commonly referred to as the bent grasses...

(Agrostis canina), Caragana

Caragana

Caragana is a genus of about 80 species of flowering plants in the family Fabaceae, native to Asia and eastern Europe.They are shrubs or small trees growing 1-6 m tall...

, smooth rupturewort

Smooth Rupturewort

Smooth Rupturewort is a plant of the family Caryophyllaceae. Growing in North America and Europe, it is believed to have diuretic properties. It contains herniarin, a methoxy analog of umbelliferone...

(Herniaria glabra), strawberry

Strawberry

Fragaria is a genus of flowering plants in the rose family, Rosaceae, commonly known as strawberries for their edible fruits. Although it is commonly thought that strawberries get their name from straw being used as a mulch in cultivating the plants, the etymology of the word is uncertain. There...

(Fragaria), and cinquefoil (Potentilla

Potentilla

Potentilla is the genus of typical cinquefoils, containing about 500 species of annual, biennial and perennial herbs in the rose family Rosaceae. They are generally Holarctic in distribution, though some may even be found in montane biomes of the New Guinea Highlands...

).

The insect was once commonly found throughout the Palearctic

Palearctic

The Palearctic or Palaearctic is one of the eight ecozones dividing the Earth's surface.Physically, the Palearctic is the largest ecozone...

and was recognised across Eurasia

Eurasia

Eurasia is a continent or supercontinent comprising the traditional continents of Europe and Asia ; covering about 52,990,000 km2 or about 10.6% of the Earth's surface located primarily in the eastern and northern hemispheres...

, from France and England to China, but it was mainly in Central Europe

Central Europe

Central Europe or alternatively Middle Europe is a region of the European continent lying between the variously defined areas of Eastern and Western Europe...

where it was common enough to make its industrial use economically viable. Excessive economic exploitation as well as the shrinking and degradation of its habitat have made the Polish cochineal a rare species. In 1994, it was included in the Ukrainian

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

Red Book of endangered species

Endangered species

An endangered species is a population of organisms which is at risk of becoming extinct because it is either few in numbers, or threatened by changing environmental or predation parameters...

. In Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

, where it was still common in the 1960s, there is insufficient data to determine its conservation status, and no protective measures are in place.

History

Ancient SlavsSlavic peoples

The Slavic people are an Indo-European panethnicity living in Eastern Europe, Southeast Europe, North Asia and Central Asia. The term Slavic represents a broad ethno-linguistic group of people, who speak languages belonging to the Slavic language family and share, to varying degrees, certain...

developed a method of obtaining red dye from the larvae of the Polish cochineal. Despite the labor-intensive process of harvesting the cochineal and a relatively modest yield, the dye continued to be a highly sought-after commodity and a popular alternative to kermes

Kermes (dye)

Kermes is a red dye derived from the dried bodies the females of a scale insect in the genus Kermes, primarily Kermes vermilio. The insects live on the sap of certain trees, especially Kermes oak tree near the Mediterranean region...

throughout the Middle Ages until it was superseded by Mexican

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

cochineal

Cochineal

The cochineal is a scale insect in the suborder Sternorrhyncha, from which the crimson-colour dye carmine is derived. A primarily sessile parasite native to tropical and subtropical South America and Mexico, this insect lives on cacti from the genus Opuntia, feeding on plant moisture and...

in the 16th century.

Dye production

Carminic acid

Carminic acid is a red glucosidal hydroxyanthrapurin that occurs naturally in some scale insects, such as the cochineal and the Polish cochineal. The insects produce the acid as a deterrent to predators. Carminic acid is the colouring agent in carmine. Synonyms are C.I. 75470 and C.I...

with traces of kermesic acid. The Polish cochineal extract's natural carminic acid content is approximately 20%. The insects were harvested shortly before the female larvae reached maturity, i.e. in late June, usually around Saint John the Baptist's day

Nativity of St. John the Baptist

The Nativity of St. John the Baptist is a Christian feast day celebrating the birth of John the Baptist, a prophet who foretold the coming of the Messiah in the person of Jesus and who baptized Jesus.-Significance:Christians have long interpreted the life of John the Baptist as a preparation for...

(June 24), hence the dye's folk name, Saint John's blood. The harvesting process involved uprooting the host plant and picking the female larvae, averaging approximately ten insects from each plant.

In Poland, including present-day Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

, and elsewhere in Europe, plantations were operated in order to deal with the high toll on the host plants. The larvae were killed with boiling water or vinegar

Vinegar

Vinegar is a liquid substance consisting mainly of acetic acid and water, the acetic acid being produced through the fermentation of ethanol by acetic acid bacteria. Commercial vinegar is produced either by fast or slow fermentation processes. Slow methods generally are used with traditional...

and dried in the sun or in an oven, ground, and dissolved in sourdough

Sourdough

Sourdough is a dough containing a Lactobacillus culture, usually in symbiotic combination with yeasts. It is one of two principal means of biological leavening in bread baking, along with the use of cultivated forms of yeast . It is of particular importance in baking rye-based breads, where yeast...

or in light rye beer called kvass

Kvass

Kvass, kvas, quass or gira, gėra is a fermented beverage made from black...

in order to remove fat. The extract could then be used for dyeing silk

Silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The best-known type of silk is obtained from the cocoons of the larvae of the mulberry silkworm Bombyx mori reared in captivity...

, wool

Wool

Wool is the textile fiber obtained from sheep and certain other animals, including cashmere from goats, mohair from goats, qiviut from muskoxen, vicuña, alpaca, camel from animals in the camel family, and angora from rabbits....

, cotton

Cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective capsule, around the seeds of cotton plants of the genus Gossypium. The fiber is almost pure cellulose. The botanical purpose of cotton fiber is to aid in seed dispersal....

, or linen

Linen

Linen is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant, Linum usitatissimum. Linen is labor-intensive to manufacture, but when it is made into garments, it is valued for its exceptional coolness and freshness in hot weather....

. The dyeing process requires roughly 3-4 oz

Ounce

The ounce is a unit of mass with several definitions, the most commonly used of which are equal to approximately 28 grams. The ounce is used in a number of different systems, including various systems of mass that form part of the imperial and United States customary systems...

of dye per pound

Pound (mass)

The pound or pound-mass is a unit of mass used in the Imperial, United States customary and other systems of measurement...

(180-250 g

Gram

The gram is a metric system unit of mass....

per kilogram

Kilogram

The kilogram or kilogramme , also known as the kilo, is the base unit of mass in the International System of Units and is defined as being equal to the mass of the International Prototype Kilogram , which is almost exactly equal to the mass of one liter of water...

) of silk and one pound of dye to color almost 20 pounds (50 g per kilogram) of wool.

Trade

Renaissance

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that spanned roughly the 14th to the 17th century, beginning in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe. The term is also used more loosely to refer to the historical era, but since the changes of the Renaissance were not...

. In the 15th and 16th centuries, along with grain, timber, and salt, it was one of Poland's and Lithuania

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state from the 12th /13th century until 1569 and then as a constituent part of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth until 1791 when Constitution of May 3, 1791 abolished it in favor of unitary state. It was founded by the Lithuanians, one of the polytheistic...

's chief exports, mainly to southern Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

and northern Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

as well as to France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

, and Armenia

Armenia

Armenia , officially the Republic of Armenia , is a landlocked mountainous country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia...

. In Poland, the cochineal trade was mostly monopolized by Jewish merchants, who bought the dye from peasants in Red Ruthenia

Red Ruthenia

Red Ruthenia is the name used since medieval times to refer to the area known as Eastern Galicia prior to World War I; first mentioned in Polish historic chronicles in the 1321, as Ruthenia Rubra or Ruthenian Voivodeship .Ethnographers explain that the term was applied from the...

and other regions of Poland and Lithuania. The merchants shipped the dye to major Polish cities such as Kraków

Kraków

Kraków also Krakow, or Cracow , is the second largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in the Lesser Poland region, the city dates back to the 7th century. Kraków has traditionally been one of the leading centres of Polish academic, cultural, and artistic life...

, Gdańsk

Gdansk

Gdańsk is a Polish city on the Baltic coast, at the centre of the country's fourth-largest metropolitan area.The city lies on the southern edge of Gdańsk Bay , in a conurbation with the city of Gdynia, spa town of Sopot, and suburban communities, which together form a metropolitan area called the...

(Danzig), and Poznań

Poznan

Poznań is a city on the Warta river in west-central Poland, with a population of 556,022 in June 2009. It is among the oldest cities in Poland, and was one of the most important centres in the early Polish state, whose first rulers were buried at Poznań's cathedral. It is sometimes claimed to be...

. From there, the merchandise was exported to wholesalers in Breslau (Wrocław), Nuremberg

Nuremberg

Nuremberg[p] is a city in the German state of Bavaria, in the administrative region of Middle Franconia. Situated on the Pegnitz river and the Rhine–Main–Danube Canal, it is located about north of Munich and is Franconia's largest city. The population is 505,664...

, Frankfurt

Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main , commonly known simply as Frankfurt, is the largest city in the German state of Hesse and the fifth-largest city in Germany, with a 2010 population of 688,249. The urban area had an estimated population of 2,300,000 in 2010...

, Augsburg

Augsburg

Augsburg is a city in the south-west of Bavaria, Germany. It is a university town and home of the Regierungsbezirk Schwaben and the Bezirk Schwaben. Augsburg is an urban district and home to the institutions of the Landkreis Augsburg. It is, as of 2008, the third-largest city in Bavaria with a...

, Venice

Venice

Venice is a city in northern Italy which is renowned for the beauty of its setting, its architecture and its artworks. It is the capital of the Veneto region...

, and other destinations. The Polish cochineal trade was a lucrative business for the Jewish intermediaries; according to Marcin of Urzędów

Marcin of Urzedów

Marcin of Urzędów was a Polish Roman Catholic priest, physician, pharmacist and botanist known especially for his Herbarz polski ....

(1595), one pound of Polish cochineal cost between four and five Venetian pounds. In terms of quantities, the trade reached its peak in the 1530s. In 1534, 1963 stones

Stone (weight)

The stone is a units of measurement that was used in many North European countries until the advent of metrication. It value, which ranged from 3 kg to 12 kg, varied from city to city and also often from commodity to commodity...

(about 30 metric tons) of the dye were sold in Poznań alone.

The advent of cheaper Mexican cochineal

Cochineal

The cochineal is a scale insect in the suborder Sternorrhyncha, from which the crimson-colour dye carmine is derived. A primarily sessile parasite native to tropical and subtropical South America and Mexico, this insect lives on cacti from the genus Opuntia, feeding on plant moisture and...

led to an abrupt slump in the Polish cochineal trade, and the 1540s saw a steep decline in quantities of the red dye exported from Poland. In 1547, Polish cochineal disappeared from the Poznań customs registry; a Volhynia

Volhynia

Volhynia, Volynia, or Volyn is a historic region in western Ukraine located between the rivers Prypiat and Southern Bug River, to the north of Galicia and Podolia; the region is named for the former city of Volyn or Velyn, said to have been located on the Southern Bug River, whose name may come...

n clerk noted in 1566 that the dye no longer paid in Gdańsk. Perennial knawel plantations were replaced with cereal fields or pastures for raising cattle. Polish cochineal, which until then was mostly an export product, continued to be used locally by the peasants who collected it; it was employed not only for dyeing fabric but also as a vodka

Vodka

Vodka , is a distilled beverage. It is composed primarily of water and ethanol with traces of impurities and flavorings. Vodka is made by the distillation of fermented substances such as grains, potatoes, or sometimes fruits....

colorant, an ingredient in folk medicine

Folk medicine

-Description:Refers to healing practices and ideas of body physiology and health preservation known to a limited segment of the population in a culture, transmitted informally as general knowledge, and practiced or applied by anyone in the culture having prior experience.All cultures and societies...

, or even for decorative coloring of horses' tails.

With the partitions of Poland

Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland or Partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth took place in the second half of the 18th century and ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland for 123 years...

at the end of the 18th century, vast markets in Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

and Central Asia

Central Asia

Central Asia is a core region of the Asian continent from the Caspian Sea in the west, China in the east, Afghanistan in the south, and Russia in the north...

opened to Polish cochineal, which became an export product again—this time, to the East. In the 19th century, Bukhara

Bukhara

Bukhara , from the Soghdian βuxārak , is the capital of the Bukhara Province of Uzbekistan. The nation's fifth-largest city, it has a population of 263,400 . The region around Bukhara has been inhabited for at least five millennia, and the city has existed for half that time...

, Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan , officially the Republic of Uzbekistan is a doubly landlocked country in Central Asia and one of the six independent Turkic states. It shares borders with Kazakhstan to the west and to the north, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to the east, and Afghanistan and Turkmenistan to the south....

, became the principal Polish cochineal trading center in Central Asia; from there the dye was shipped to Kashgar

Kashgar

Kashgar or Kashi is an oasis city with approximately 350,000 residents in the western part of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China. Kashgar is the administrative centre of Kashgar Prefecture which has an area of 162,000 km² and a population of approximately...

in Xinjiang

Xinjiang

Xinjiang is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. It is the largest Chinese administrative division and spans over 1.6 million km2...

, and Kabul

Kabul

Kabul , spelt Caubul in some classic literatures, is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. It is also the capital of the Kabul Province, located in the eastern section of Afghanistan...

and Herat

Herat

Herāt is the capital of Herat province in Afghanistan. It is the third largest city of Afghanistan, with a population of about 397,456 as of 2006. It is situated in the valley of the Hari River, which flows from the mountains of central Afghanistan to the Karakum Desert in Turkmenistan...

in Afghanistan

Afghanistan

Afghanistan , officially the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located in the centre of Asia, forming South Asia, Central Asia and the Middle East. With a population of about 29 million, it has an area of , making it the 42nd most populous and 41st largest nation in the world...

. It is possible that the Polish dye was used to manufacture some of the famous oriental rug

Oriental rug

An authentic oriental rug is a handmade carpet that is either knotted with pile or woven without pile.By definition - Oriental rugs are rugs that come from the orient...

s.

Studies

Herbal

AThe use of a or an depends on whether or not herbal is pronounced with a silent h. herbal is "a collection of descriptions of plants put together for medicinal purposes." Expressed more elaborately — it is a book containing the names and descriptions of plants, usually with information on their...

) by Marcin of Urzędów

Marcin of Urzedów

Marcin of Urzędów was a Polish Roman Catholic priest, physician, pharmacist and botanist known especially for his Herbarz polski ....

(1595), where it was described as "small red seeds" that grow under plant roots, becoming "ripe" in April and from which a little "bug" emerges in June. The first scientific comments by non-Polish authors were written by Segerius (1670) and von Bernitz (1672). In 1731, Johann Philipp Breyne

Johann Philipp Breyne

Johann Philipp Breyne , son of Jacob Breyne , was a German botanist, palaeontologist, zoologist and entomologist. He is best known for his work on the Polish cochineal , an insect formerly used in production of red dye...

, wrote (translated into English during the same century), the first major treatise about the insect, including the results of his research on its physiology and life cycle. In 1934, Polish biologist Antoni Jakubski

Antoni Jakubski

Antoni Władysław Jakubski was a Polish zoologist and explorer.Jakubski was born in Lemberg , Galicia, Austria-Hungary on 28 March 1885. He studied zoology from Prof. Józef Nusbaum-Hilarowicz at the Lwów University where he received a habilitation in 1917...

wrote (Polish cochineal), a monograph taking into account both the insect's biology and historical role.

Linguistics

The historical importance of the Polish cochineal is still reflected in most modern Slavic languagesSlavic languages

The Slavic languages , a group of closely related languages of the Slavic peoples and a subgroup of Indo-European languages, have speakers in most of Eastern Europe, in much of the Balkans, in parts of Central Europe, and in the northern part of Asia.-Branches:Scholars traditionally divide Slavic...

where the words for the color red and for the month of June both derive from the Proto-Slavic

Proto-Slavic language

Proto-Slavic is the proto-language from which Slavic languages later emerged. It was spoken before the seventh century AD. As with most other proto-languages, no attested writings have been found; the language has been reconstructed by applying the comparative method to all the attested Slavic...

(probably pronounced t͡ʃĭrwĭ), meaning "a worm" or "larva". (See examples in the table below.) In the Czech language

Czech language

Czech is a West Slavic language with about 12 million native speakers; it is the majority language in the Czech Republic and spoken by Czechs worldwide. The language was known as Bohemian in English until the late 19th century...

, as well as old Bulgarian

Bulgarian months

The months of the year used with the Gregorian calendar by Bulgarians bear names derived from the Latin month names and these are used by the Bulgarian population...

, this is true for both June and July, the two months when harvest of the insect's larvae was possible. In modern Polish

Polish language

Polish is a language of the Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages, used throughout Poland and by Polish minorities in other countries...

, is a word for June, as well as for the Polish cochineal () and its host plant, the perennial knawel ().

| English | Belarusian Belarusian language The Belarusian language , sometimes referred to as White Russian or White Ruthenian, is the language of the Belarusian people... |

Ukrainian Ukrainian language Ukrainian is a language of the East Slavic subgroup of the Slavic languages. It is the official state language of Ukraine. Written Ukrainian uses a variant of the Cyrillic alphabet.... |

Polish Polish language Polish is a language of the Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages, used throughout Poland and by Polish minorities in other countries... |

Czech Czech language Czech is a West Slavic language with about 12 million native speakers; it is the majority language in the Czech Republic and spoken by Czechs worldwide. The language was known as Bohemian in English until the late 19th century... |

Croatian Croatian language Croatian is the collective name for the standard language and dialects spoken by Croats, principally in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Serbian province of Vojvodina and other neighbouring countries... |

Bulgarian Bulgarian language Bulgarian is an Indo-European language, a member of the Slavic linguistic group.Bulgarian, along with the closely related Macedonian language, demonstrates several linguistic characteristics that set it apart from all other Slavic languages such as the elimination of case declension, the... |

| worm, larva |

|

|

|

|||

| red (adj.) | |

|

|

|||

| June | |

|

|

|||

| July | |

|||||

| Polish cochineal |

|

|

||||