.gif)

Politics (Aristotle)

Encyclopedia

Aristotle

's Politics (Greek

Πολιτικά) is a work of political philosophy

. The end of the Nicomachean Ethics declared that the inquiry into ethics necessarily follows into politics, and the two works are frequently considered to be parts of a larger treatise, or perhaps connected lectures, dealing with the "philosophy of human affairs." The title of the Politics literally means "the things concerning the polis

."

Werner Jaeger

suggested that the Politics actually represents the conflation of two, distinct treatises. The first (Books I-III, VII-VIII) would represent a less mature work from when Aristotle had not yet fully broken from Plato

, and consequently show a greater emphasis on the best regime. The second (Books IV-VI) would be more empirically minded, and thus belong to a later stage of development.

Carnes Lord has argued against the sufficiency of this view, however, noting the numerous cross-references between Jaeger's supposedly separate works and questioning the difference in tone that Jaeger saw between them. For example, Book IV explicitly notes the utility of examining actual regimes (Jaeger's "empirical" focus) in determining the best regime (Jaeger's "Platonic" focus). Instead, Lord suggests that the Politics is indeed a finished treatise, and that Books VII and VIII do belong in between Books III and IV; he attributes their current ordering to a merely mechanical transcription error.

) or "political community" (koinōnia politikē) as opposed to other types of communities and partnerships such as the household and village. He begins with the relationship between the city and man (I. 1–2), and then specifically discusses the household (I. 3–13). He takes issue with the view that political rule, kingly rule, rule over slaves, and rule over a household or village are only different in terms of size. He then examines in what way the city may be said to be natural.

Aristotle discusses the parts of the household, which includes slaves, leading to a discussion of whether slavery can ever be just and better for the person enslaved or is always unjust and bad. He distinguishes between those who are slaves because the law says they are and those who are slaves by nature

, saying the inquiry hinges on whether there are any such natural slaves. Only someone as different from other people as the body is from the soul or beasts are from human beings would be a slave by nature, Aristotle concludes, all others being slaves solely by law or convention. Some scholars have therefore concluded that the qualifications for natural slavery preclude the existence of such a being.

Aristotle then moves to the question of property in general, arguing that the acquisition of property does not form a part of household management (oikonomike) and criticizing those who take it too seriously. It is necessary, but that does not make it a part of household management any more than it makes medicine a part of household management just because health is necessary. He criticizes income based upon trade and says that those who become avaricious do so because they forget that money merely symbolizes wealth without being wealth.

Book I concludes with Aristotle's assertion that the proper object of household rule is the virtuous character of one's wife and children, not the management of slaves or the acquisition of property. Rule over the slaves is despotic, rule over children kingly, and rule over one's wife political (except there is no rotation in office). Aristotle questions whether it is sensible to speak of the "virtue" of a slave and whether the "virtues" of a wife and children are the same as those of a man before saying that because the city must be concerned that its women and children be virtuous, the virtues that the father should instill are dependent upon the regime and so the discussion must turn to what has been said about the best regime.

's Republic

(2. 1–5) before moving to that presented in Plato's Laws (2. 6). Aristotle then discusses the systems presented by two other philosophers, Phaleas of Chalcedon

(2. 7) and Hippodamus of Miletus

(2. 8).

After addressing regimes invented by theorists, Aristotle moves to the examination of three regimes that are commonly held to be well managed. These are the Spartan

(2. 9), Cretan (2. 10), and Carthaginian (2. 11). The book concludes with some observations on regimes and legislators.

"He who has the power to take part in the deliberative or judicial administration of any state is said by us to be a citizen of that state; and speaking generally, a state is a body of citizens sufficing for the purpose of life. But in practice a citizen is defined to be one of whom both the parents are citizens; others insist on going further back; say two or three or more grandparents."

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

's Politics (Greek

Greek language

Greek is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages. Native to the southern Balkans, it has the longest documented history of any Indo-European language, spanning 34 centuries of written records. Its writing system has been the Greek alphabet for the majority of its history;...

Πολιτικά) is a work of political philosophy

Political philosophy

Political philosophy is the study of such topics as liberty, justice, property, rights, law, and the enforcement of a legal code by authority: what they are, why they are needed, what, if anything, makes a government legitimate, what rights and freedoms it should protect and why, what form it...

. The end of the Nicomachean Ethics declared that the inquiry into ethics necessarily follows into politics, and the two works are frequently considered to be parts of a larger treatise, or perhaps connected lectures, dealing with the "philosophy of human affairs." The title of the Politics literally means "the things concerning the polis

Polis

Polis , plural poleis , literally means city in Greek. It could also mean citizenship and body of citizens. In modern historiography "polis" is normally used to indicate the ancient Greek city-states, like Classical Athens and its contemporaries, so polis is often translated as "city-state."The...

."

Composition

The literary character of the Politics is subject to some dispute, growing out of the textual difficulties that attended the loss of Aristotle's works. Book III ends with a sentence that is repeated almost verbatim at the start of Book VII, while the intervening Books IV-VI seem to have a very different flavor from the rest; Book IV seems to refer several times back to the discussion of the best regime contained in Books VII-VIII. Some editors have therefore inserted Books VII-VIII after Book III. At the same time, however, references to the "discourses on politics" that occur in the Nicomachean Ethics suggest that the treatise as a whole ought to conclude with the discussion of education that occurs in Book VIII of the Politics, although it is not certain that Aristotle is referring to the Politics here.Werner Jaeger

Werner Jaeger

Werner Wilhelm Jaeger was a classicist of the 20th century.Jaeger was born in Lobberich, Rhenish Prussia. He attended school at Lobberich and at the Gymnasium Thomaeum in Kempen Jaeger studied at the University of Marburg and University of Berlin. He received a Ph.D...

suggested that the Politics actually represents the conflation of two, distinct treatises. The first (Books I-III, VII-VIII) would represent a less mature work from when Aristotle had not yet fully broken from Plato

Plato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

, and consequently show a greater emphasis on the best regime. The second (Books IV-VI) would be more empirically minded, and thus belong to a later stage of development.

Carnes Lord has argued against the sufficiency of this view, however, noting the numerous cross-references between Jaeger's supposedly separate works and questioning the difference in tone that Jaeger saw between them. For example, Book IV explicitly notes the utility of examining actual regimes (Jaeger's "empirical" focus) in determining the best regime (Jaeger's "Platonic" focus). Instead, Lord suggests that the Politics is indeed a finished treatise, and that Books VII and VIII do belong in between Books III and IV; he attributes their current ordering to a merely mechanical transcription error.

Book I

In the first book, Aristotle discusses the city (polisPolis

Polis , plural poleis , literally means city in Greek. It could also mean citizenship and body of citizens. In modern historiography "polis" is normally used to indicate the ancient Greek city-states, like Classical Athens and its contemporaries, so polis is often translated as "city-state."The...

) or "political community" (koinōnia politikē) as opposed to other types of communities and partnerships such as the household and village. He begins with the relationship between the city and man (I. 1–2), and then specifically discusses the household (I. 3–13). He takes issue with the view that political rule, kingly rule, rule over slaves, and rule over a household or village are only different in terms of size. He then examines in what way the city may be said to be natural.

Aristotle discusses the parts of the household, which includes slaves, leading to a discussion of whether slavery can ever be just and better for the person enslaved or is always unjust and bad. He distinguishes between those who are slaves because the law says they are and those who are slaves by nature

Natural slavery

Natural slavery is term used by Aristotle in the Politics to express the belief that some people are slaves by nature, contrasting them with those who were slaves solely by law or convention.-Aristotle's discussion:...

, saying the inquiry hinges on whether there are any such natural slaves. Only someone as different from other people as the body is from the soul or beasts are from human beings would be a slave by nature, Aristotle concludes, all others being slaves solely by law or convention. Some scholars have therefore concluded that the qualifications for natural slavery preclude the existence of such a being.

Aristotle then moves to the question of property in general, arguing that the acquisition of property does not form a part of household management (oikonomike) and criticizing those who take it too seriously. It is necessary, but that does not make it a part of household management any more than it makes medicine a part of household management just because health is necessary. He criticizes income based upon trade and says that those who become avaricious do so because they forget that money merely symbolizes wealth without being wealth.

Book I concludes with Aristotle's assertion that the proper object of household rule is the virtuous character of one's wife and children, not the management of slaves or the acquisition of property. Rule over the slaves is despotic, rule over children kingly, and rule over one's wife political (except there is no rotation in office). Aristotle questions whether it is sensible to speak of the "virtue" of a slave and whether the "virtues" of a wife and children are the same as those of a man before saying that because the city must be concerned that its women and children be virtuous, the virtues that the father should instill are dependent upon the regime and so the discussion must turn to what has been said about the best regime.

Book II

Book II examines various views concerning the best regime. It opens with an analysis of the regime presented in PlatoPlato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

's Republic

Republic (Plato)

The Republic is a Socratic dialogue written by Plato around 380 BC concerning the definition of justice and the order and character of the just city-state and the just man...

(2. 1–5) before moving to that presented in Plato's Laws (2. 6). Aristotle then discusses the systems presented by two other philosophers, Phaleas of Chalcedon

Phaleas of Chalcedon

Phaleas of Chalcedon was a Greek statesman of antiquity, who argued that all citizens of a model city should be equal in property and education....

(2. 7) and Hippodamus of Miletus

Hippodamus of Miletus

Hippodamus of Miletos was an ancient Greek architect, urban planner, physician, mathematician, meteorologist and philosopher and is considered to be the “father” of urban planning, the namesake of Hippodamian plan of city layouts...

(2. 8).

After addressing regimes invented by theorists, Aristotle moves to the examination of three regimes that are commonly held to be well managed. These are the Spartan

Spartan Constitution

The Spartan Constitution, or Politeia, refers to the government and laws of the Dorian city-state of Sparta from the time of Lycurgus, the legendary law-giver, to the incorporation of Sparta into the Roman Empire: approximately the 8th century BC to the 2nd century BC, Every city-state of Greece...

(2. 9), Cretan (2. 10), and Carthaginian (2. 11). The book concludes with some observations on regimes and legislators.

Book III

- Who is a citizen?

"He who has the power to take part in the deliberative or judicial administration of any state is said by us to be a citizen of that state; and speaking generally, a state is a body of citizens sufficing for the purpose of life. But in practice a citizen is defined to be one of whom both the parents are citizens; others insist on going further back; say two or three or more grandparents."

- Classification of constitution.

- Just distribution of political power.

- Types of monarchies:-

- Monarchy: exercised over voluntary subjects, but limited to certain functions; the king was a general and a judge, and had control of religion.

- Absolute: government of one for the absolute good

- Barbarian: legal and hereditary+ willing subjects

- Dictator: installed by foreign power elective dictatorship + willing subjects (elective tyranny)

Book IV

- Tasks of political theory

- Why are there many types of constitutions?

- Types of democracies

- Types of oligarchies

- Polity as the optimal constitution

- Government offices

Book V

- Constitutional change

- Revolutions in different types of constitutions and ways to preserve constitutions

- Instability of tyrannies

Book VII

- Best state and best life

- Ideal state. Its population, territory, position etc.

- Citizens of the ideal state

- Marriage and children

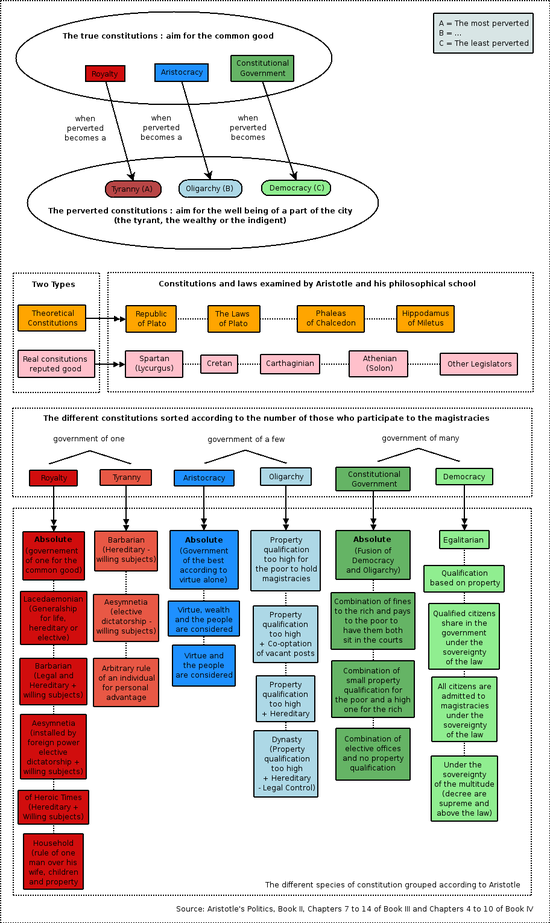

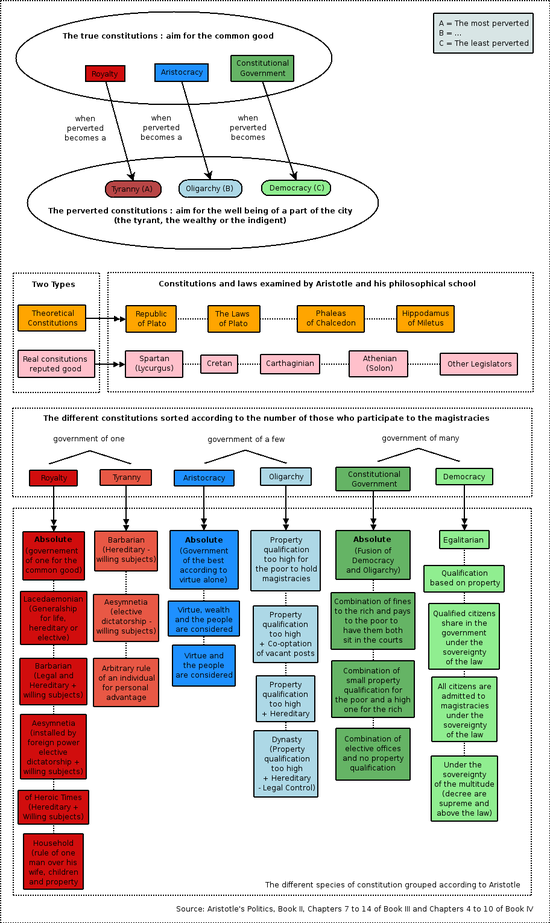

Aristotle's classification

After studying a number of real and theoretical city-state's constitutions, Aristotle classified them according to various criteria. On one side stand the true (or good) constitutions, which are considered such because they aim for the common good, and on the other side the perverted (or deviant) ones, considered such because they aim for the well being of only a part of the city. The constitutions are then sorted according to the "number" of those who participate to the magistracies: one, a few, or many. Aristotle's sixfold classification is slightly different from the one found in The Statesman by Plato. The diagram above illustrates Aristotle's classification.External links

Versions- Politics full text by Project GutenbergProject GutenbergProject Gutenberg is a volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, to "encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks". Founded in 1971 by Michael S. Hart, it is the oldest digital library. Most of the items in its collection are the full texts of public domain books...

- English translation at Perseus Digital Library translation by Harris Rackham

- Australian copy trans. by Benjamin JowettBenjamin JowettBenjamin Jowett was renowned as an influential tutor and administrative reformer in the University of Oxford, a theologian and translator of Plato. He was Master of Balliol College, Oxford.-Early career:...

- HTML trans. by Benjamin Jowett

- PDF at McMaster trans. by Benjamin Jowett