Principle of individuation

Encyclopedia

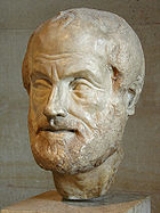

The Principle of Individuation is a criterion which supposedly individuates or numerically distinguishes the members of the kind for which it is given, i.e. by which we can supposedly determine, regarding any kind of thing, when we have more than one of them or not. It is also known as a 'criterion of identity' or 'indiscernibility principle'. The history of the consideration of such a principle begins with Aristotle

. It was much discussed by the medieval philosophers

, particularly Bonaventura and Scotus, and later by Francisco Suarez

and Leibniz. Some philosophers have denied the need for any such principle.

Taking issue with the view expressed in certain Platonic dialogues that universal Forms (such as the Good, the Just, the Triangular and so on) constitute reality, Aristotle regarded an individual as something real in itself. An individual therefore has two kinds of unity: specific and numerical. Specific unity (i.e. unity of the species

Taking issue with the view expressed in certain Platonic dialogues that universal Forms (such as the Good, the Just, the Triangular and so on) constitute reality, Aristotle regarded an individual as something real in itself. An individual therefore has two kinds of unity: specific and numerical. Specific unity (i.e. unity of the species

to which an individual belongs) is a unity of nature which the individual shares with other individuals. For example, twin daughters are both human females, and share a unity of nature. This specific unity, according to Aristotle, is derived from Form, for it is form (which the medieval philosophers called quiddity

) which makes an individual substance the kind of thing it is. But two individuals (such as the twins) can share exactly the same form, yet not be one in number. What is the principle by which two individuals differ in number alone? This cannot be a common property. As Bonaventure

later argued, there is no form of which we cannot imagine a similar one, thus there can be 'identical' twins, triplets, quadruplets and so on. For any such form would then be common to several things, and therefore not an individual at all. What is the criterion for a thing being an individual?

In a passage much-quoted by the medievals, Aristotle attributes the cause of individuation to matter:

, where he says that things which are individuals and are discrete only in number, differ only by accidental properties. The Persian philosopher Avicenna

(980-1037) first introduced a term which was later translated into Latin

as signatum, meaning 'determinate individual'. Avicenna argues that a nature is not of itself individual, the relation between it and individuality is an accidental one, and we must look for its source not in its essence, but among accidental attributes such as quantity, quality, space and time. However, he did not work out any definite or detailed theory of individuation. His successor Averroes

(1126–1198) argued that matter is numerically one, since it is undetermined in itself and has no definite boundaries. However, since it is divisible, this must be caused by quantity, and matter must therefore have the potential for determination in three dimensions (in the same way a rough and unhewn lump of marble has the potential to be sculpted into a statue).

The theories of Averroes and Avicenna had a great influence on the later theory of Thomas Aquinas

(1224–1274). Aquinas never doubted the Aristotelian theory of individuation by matter, but was uncertain which of the theories of Avicenna or Averroes are correct. He first accepted the theory of Avicenna that the principle of individuation is matter designated (signata) by determinate dimensions, but later abandoned this in favour of the Averroist theory that it is matter affected by unterminated dimension which is the principle. Later still, he seems to have returned to the first theory when he wrote the Quodlibeta

(1243–1316) believed that individuation happens by the quantity in the matter.

Duns Scotus

(1265–1308) held that individuation comes from the numerical determination of form and matter whereby they become this form and this matter. Individuation is distinguished from a nature by means of a formal distinction

on the side of the thing. Later followers of Scotus called this principle haecceity

or 'thisness'. The nominalist philosopher William of Ockham

(1300–1348) regarded the principle as unnecessary and indeed meaningless, since there are no realities independent of individual things. An individual is distinct of itself, not multiplied in a species, since species are not real (they correspond only to concepts in our mind). His contemporary Durandus

held that individuation comes about through actual existence. Thus the common nature and the individual nature differ only as one conceived and one existing.

The late scholastic philosopher Francisco Suarez

(1548–1617) held, in opposition to Scotus, that the principle of individuation can only be logically distinguished from the individual being. Every being, even an incomplete one, is individual of itself, by reason of its being a thing. Suárez maintained that, although the humanity of Socrates does not differ from that of Plato, yet they do not constitute in reality one and the same humanity; there are as many "formal unities" (in this case, humanities) as there are individuals, and these individuals do not constitute a factual, but only an essential or ideal unity. The formal unity, however, is not an arbitrary creation of the mind, but exists in the nature of the thing before any operation of the understanding.

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

. It was much discussed by the medieval philosophers

Medieval philosophy

Medieval philosophy is the philosophy in the era now known as medieval or the Middle Ages, the period roughly extending from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century AD to the Renaissance in the sixteenth century...

, particularly Bonaventura and Scotus, and later by Francisco Suarez

Francisco Suárez

Francisco Suárez was a Spanish Jesuit priest, philosopher and theologian, one of the leading figures of the School of Salamanca movement, and generally regarded among the greatest scholastics after Thomas Aquinas....

and Leibniz. Some philosophers have denied the need for any such principle.

Aristotle

Species

In biology, a species is one of the basic units of biological classification and a taxonomic rank. A species is often defined as a group of organisms capable of interbreeding and producing fertile offspring. While in many cases this definition is adequate, more precise or differing measures are...

to which an individual belongs) is a unity of nature which the individual shares with other individuals. For example, twin daughters are both human females, and share a unity of nature. This specific unity, according to Aristotle, is derived from Form, for it is form (which the medieval philosophers called quiddity

Quiddity

In scholastic philosophy, quiddity was another term for the essence of an object, literally its "whatness," or "what it is." The term derives from the Latin word "quidditas," which was used by the medieval scholastics as a literal translation of the equivalent term in Aristotle's Greek.It...

) which makes an individual substance the kind of thing it is. But two individuals (such as the twins) can share exactly the same form, yet not be one in number. What is the principle by which two individuals differ in number alone? This cannot be a common property. As Bonaventure

Bonaventure

Saint Bonaventure, O.F.M., , born John of Fidanza , was an Italian medieval scholastic theologian and philosopher. The seventh Minister General of the Order of Friars Minor, he was also a Cardinal Bishop of Albano. He was canonized on 14 April 1482 by Pope Sixtus IV and declared a Doctor of the...

later argued, there is no form of which we cannot imagine a similar one, thus there can be 'identical' twins, triplets, quadruplets and so on. For any such form would then be common to several things, and therefore not an individual at all. What is the criterion for a thing being an individual?

In a passage much-quoted by the medievals, Aristotle attributes the cause of individuation to matter:

Boethius to Aquinas

The late Roman philosopher Boethius (480–524) touches upon the subject in his IsagogeIsagoge

The Isagoge or "Introduction" to Aristotle's "Categories", written by Porphyry in Greek and translated into Latin by Boethius, was the standard textbook on logic for at least a millennium after his death. It was composed by Porphyry in Sicily during the years 268-270, and sent to Chrysaorium,...

, where he says that things which are individuals and are discrete only in number, differ only by accidental properties. The Persian philosopher Avicenna

Avicenna

Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Sīnā , commonly known as Ibn Sīnā or by his Latinized name Avicenna, was a Persian polymath, who wrote almost 450 treatises on a wide range of subjects, of which around 240 have survived...

(980-1037) first introduced a term which was later translated into Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

as signatum, meaning 'determinate individual'. Avicenna argues that a nature is not of itself individual, the relation between it and individuality is an accidental one, and we must look for its source not in its essence, but among accidental attributes such as quantity, quality, space and time. However, he did not work out any definite or detailed theory of individuation. His successor Averroes

Averroes

' , better known just as Ibn Rushd , and in European literature as Averroes , was a Muslim polymath; a master of Aristotelian philosophy, Islamic philosophy, Islamic theology, Maliki law and jurisprudence, logic, psychology, politics, Arabic music theory, and the sciences of medicine, astronomy,...

(1126–1198) argued that matter is numerically one, since it is undetermined in itself and has no definite boundaries. However, since it is divisible, this must be caused by quantity, and matter must therefore have the potential for determination in three dimensions (in the same way a rough and unhewn lump of marble has the potential to be sculpted into a statue).

The theories of Averroes and Avicenna had a great influence on the later theory of Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, O.P. , also Thomas of Aquin or Aquino, was an Italian Dominican priest of the Catholic Church, and an immensely influential philosopher and theologian in the tradition of scholasticism, known as Doctor Angelicus, Doctor Communis, or Doctor Universalis...

(1224–1274). Aquinas never doubted the Aristotelian theory of individuation by matter, but was uncertain which of the theories of Avicenna or Averroes are correct. He first accepted the theory of Avicenna that the principle of individuation is matter designated (signata) by determinate dimensions, but later abandoned this in favour of the Averroist theory that it is matter affected by unterminated dimension which is the principle. Later still, he seems to have returned to the first theory when he wrote the Quodlibeta

Scotus to Suarez

Giles of RomeGiles of Rome

Giles of Rome , was an archbishop of Bourges who was famed for his logician commentary on the Organon by Aristotle. Giles was styled Doctor Fundatissimus by Pope Benedict XIV...

(1243–1316) believed that individuation happens by the quantity in the matter.

Duns Scotus

Duns Scotus

Blessed John Duns Scotus, O.F.M. was one of the more important theologians and philosophers of the High Middle Ages. He was nicknamed Doctor Subtilis for his penetrating and subtle manner of thought....

(1265–1308) held that individuation comes from the numerical determination of form and matter whereby they become this form and this matter. Individuation is distinguished from a nature by means of a formal distinction

Formal distinction

In scholastic metaphysics, a formal distinction is a distinction intermediate between what is merely conceptual, and what is fully real or mind-independent...

on the side of the thing. Later followers of Scotus called this principle haecceity

Haecceity

Haecceity is a term from medieval philosophy first coined by Duns Scotus which denotes the discrete qualities, properties or characteristics of a thing which make it a particular thing...

or 'thisness'. The nominalist philosopher William of Ockham

William of Ockham

William of Ockham was an English Franciscan friar and scholastic philosopher, who is believed to have been born in Ockham, a small village in Surrey. He is considered to be one of the major figures of medieval thought and was at the centre of the major intellectual and political controversies of...

(1300–1348) regarded the principle as unnecessary and indeed meaningless, since there are no realities independent of individual things. An individual is distinct of itself, not multiplied in a species, since species are not real (they correspond only to concepts in our mind). His contemporary Durandus

Durandus of Saint-Pourçain

Durandus of Saint-Pourçain , was a French philosopher and theologian.He was born at Saint-Pourçain, Auvergne, and entered the Dominican Order at Clermont, and obtained the doctoral degree at Paris in 1313...

held that individuation comes about through actual existence. Thus the common nature and the individual nature differ only as one conceived and one existing.

The late scholastic philosopher Francisco Suarez

Francisco Suárez

Francisco Suárez was a Spanish Jesuit priest, philosopher and theologian, one of the leading figures of the School of Salamanca movement, and generally regarded among the greatest scholastics after Thomas Aquinas....

(1548–1617) held, in opposition to Scotus, that the principle of individuation can only be logically distinguished from the individual being. Every being, even an incomplete one, is individual of itself, by reason of its being a thing. Suárez maintained that, although the humanity of Socrates does not differ from that of Plato, yet they do not constitute in reality one and the same humanity; there are as many "formal unities" (in this case, humanities) as there are individuals, and these individuals do not constitute a factual, but only an essential or ideal unity. The formal unity, however, is not an arbitrary creation of the mind, but exists in the nature of the thing before any operation of the understanding.

External links

- The problem of individuation in the Middle Ages (Peter King)

- Medieval theories of haecceity, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Individual, Catholic Encyclopedia

- Henry of Ghent's theory of Individuation, Proceedings of the Society for Medieval Logic and Metaphysics, Volume 5, 2005 Martin Pickavé, pp. 38–49.