Procellariidae

Encyclopedia

The family

Procellariidae is a group of seabird

s that comprises the fulmarine petrel

s, the gadfly petrel

s, the prions

, and the shearwater

s. This family is part of the bird

order Procellariiformes

(or tubenoses), which also includes the albatross

es, the storm-petrel

s, and the diving petrel

s.

The procellariids are the most numerous family of tubenoses, and the most diverse. They range in size from the giant petrel

s, which are almost as large as the albatrosses, to the prions, which are as small as the larger storm-petrels. They feed on fish

, squid

and crustacea, with many also taking fisheries discards

and carrion

. All species are accomplished long-distance foragers, and many undertake long trans-equatorial

migrations

. They are colonial breeders, exhibiting long-term mate fidelity

and site philopatry

. In all species, each pair lays a single egg

per breeding season. Their incubation times and chick-rearing periods are exceptionally long compared to other birds.

Many procellariids have breeding populations of over several million pairs; others number fewer than 200 birds. Humans have traditionally exploited several species of fulmar

and shearwater (known as muttonbird

s) for food, fuel, and bait, a practice that continues in a controlled fashion today. Several species are threatened by introduced species

attacking adults and chicks in breeding colonies and by long-line fisheries

.

phylogenetic relationships by Sibley and Ahlquist

, the split of the Procellariiformes

into the four families occurred around 30 million years ago; a fossil

bone often attributed to the order, described as the genus Tytthostonyx

, has been found in rocks dating around the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary

(70-60 mya), but the remains are too incomplete for placement within the Procellariiformes to be certain.

The molecular evidence suggests that the storm-petrels were the first to diverge from the ancestral stock, and the albatrosses next, with the procellariids and diving petrels splitting most recently. Many taxonomists used to retain the diving petrel

s in this family also, but today their distinctiveness is considered well supported.

However, modern procellariid genera began to appear possibly just as early as the proposed splitting of the family, with a Rupelian

(Early Oligocene

) fossil from Belgium

tentatively attributed to the shearwater genus Puffinus,

and most modern genera were established by the Miocene

. Thus, a basal radiation of the Procellariiformes in the Eocene

at least (as with many modern orders of birds) seems likely, especially given that significant anomalies in molecular evolution rates and patterns have been discovered in the entire family (see also Leach's Storm-petrel

), and molecular dates must be considered extremely tentative. Some genera (Argyrodyptes, Pterodromoides) are only known from fossils. Eopuffinus from the Late Paleocene is sometimes placed in the Procellariidae, but even its placement in the Procellariiformes is quite doubtful.

Sibley and Ahlquist's taxonomy has included all the members of the Procellariiformes inside the Procellariidae and that family in an enlarged Ciconiiformes

, but this change has not been widely accepted.

The procellariid family is usually broken up into four fairly distinct groups; the fulmarine petrel

The procellariid family is usually broken up into four fairly distinct groups; the fulmarine petrel

s, the gadfly petrel

s, the prions

, and the shearwater

s.

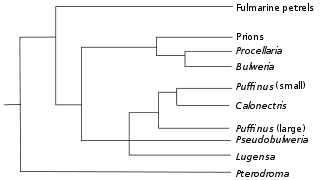

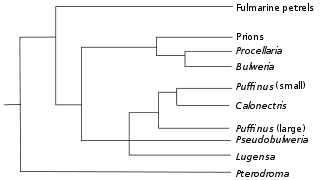

The more traditional taxonomy of the family, particularly the split into four groups, has been challenged by recent research. A 1998 study by Gary Nunn and Scott Stanley showed that the fulmarine petrels were indeed a discrete group within the family, as were the gadfly petrels in the genus Pterodroma.

The more traditional taxonomy of the family, particularly the split into four groups, has been challenged by recent research. A 1998 study by Gary Nunn and Scott Stanley showed that the fulmarine petrels were indeed a discrete group within the family, as were the gadfly petrels in the genus Pterodroma.

However the two petrels in the genus Bulweria are no longer considered close to the gadfly petrels, instead being moved closer to the shearwaters in the genus Procellaria. Two genera, Pseudobulweria

and Lugensa, have been split from the gadfly petrel genus Pterodroma, with Pseudobulweria being phylogenetically closer to the Puffinus shearwaters than the Pterodroma gadfly petrels,

and Lugensa (the Kerguelen Petrel

) possibly being closely related to the shearwaters or the fulmars.

The prions, according to Nunn and Stanley, were amongst the larger shearwater group. The Calonectris shearwaters were placed close to the two Puffinus clades (closer to the Puffinus, or small, clade) and both were distant to the Procellaria shearwaters. The relationships between the genera and within the genera are still the subject of debate, with researchers lumping and splitting

the species and genera within the family and arguing about the position of the genera within the family. Many of the confusing species are amongst the least known of all seabirds; some of them (like the Fiji Petrel

) have not been seen more than 10 times since their discovery by science, and others' breeding grounds are unknown (like the Heinroth's Shearwater

).

There are around 80 species

of procellariid in 14 genera

. For a complete list, and notes on different taxonomies, see List of Procellariidae.

s with a wingspan of 81 to 99 cm (31.9 to 39 in), are almost as large as albatross

es; the smallest, such as the Fairy Prion

have a wingspan of 23 to 28 cm (9.1 to 11 in), are slightly bigger than the diving petrel

s. There are no obvious differences between the sexes, although females tend to be slighter. Like all Procellariiformes, the procellariids have a characteristic tubular nasal passage which is used for olfaction. This ability to smell helps to locate patchily distributed prey at sea and may also help locate nesting colonies. The plumage

of the procellariids is usually dull, with greys, blues, blacks and browns being the usual colours, although some species have striking patterns (such as the Cape Petrel

).

The technique of flight

The technique of flight

among procellariids depends on foraging methods. Compared to an average bird, all procellariids have a high aspect ratio

(meaning their wings are long and narrow) and a heavy wing loading

. Therefore they must maintain a high speed in order to remain in the air. Most procellariids use two techniques to do this, namely, dynamic soaring

and slope soaring. Dynamic soaring involves gliding across wave fronts, thus taking advantage of the vertical wind gradient

and minimising the effort required to stay in the air. Slope soaring is more straightforward: the procellariid turns to the wind, gaining height, from where it can then glide back down to the sea. Most procellariids aid their flight by means of flap-glides, where bursts of flapping are followed by a period of gliding; the amount of flapping dependent on the strength of the wind and the choppiness of the water. Shearwaters and other larger petrels, which have lower aspect ratio, must make more use of flapping to remain airborne than gadfly petrels. Because of the high speeds required for flight, procellariids need to either run or face into a strong wind in order to take off.

The giant petrels share with the albatrosses an adaptation known as a shoulder-lock: a sheet of tendon

The giant petrels share with the albatrosses an adaptation known as a shoulder-lock: a sheet of tendon

which locks the wing when fully extended, allowing the wing to be kept up and out without any muscle effort. Gadfly petrels often feed on the wing, snapping prey without landing on the water. The flight of the smaller prions is similar to that of the storm-petrel

s, being highly erratic and involving weaving and even looping the loop. The wings of all species are long and stiff. In some species of shearwater the wings are also used to power the birds underwater while diving for prey. Their heavier wing loadings, in comparison with surface-feeding procellariids, allow these shearwaters to achieve considerable depths below 70 m (229.7 ft) in the case of the Short-tailed Shearwater

).

Procellariids generally have weak legs which are set back, and many species move around on land by resting on the breast and pushing themselves forward, often with the help of their wings. The exception to this is the two species of giant petrel, which like the albatrosses, have strong legs used to feed on land (see below). The feet of shearwaters are set far back on the body for swimming and are of little use when on the ground.

and Hudson Bay

, but are present year round or seasonally in the rest. The seas north of New Zealand

are the centre of procellariid biodiversity

, with the most species. Among the four groups, the fulmarine petrel

s have a mostly polar

distribution, with most species living around Antarctica and one, the Northern Fulmar

ranging in the Northern Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The prion

s are restricted to the Southern Ocean

, and the gadfly petrel

s are found mostly in the tropics with some temperate species. The shearwater

s are the most widespread group and breed in most temperate and tropical seas, although by a biogeographical

quirk are absent as breeders from the North Pacific.

Many procellariids undertake long annual migrations

Many procellariids undertake long annual migrations

in the non-breeding season. Southern species of shearwater such as the Sooty Shearwater

and Short-tailed Shearwater

, breeding on islands off Australia

, New Zealand and Chile

, undertake transequatorial migrations of millions of birds up to the waters off Alaska

and back each year during the austral winter. Manx Shearwater

s from the North Atlantic also undertake transequatorial migrations from Western Europe and North America to the waters off Brazil in the South Atlantic. The mechanisms of navigation

are poorly understood, but displacement experiments where individuals were removed from colonies and flown to far-flung release sites have shown that they are able to home in on their colonies with remarkable precision. A Manx Shearwater released in Boston returned to its colony in Skomer

, Wales

within 13 days, a distance of 5,150 kilometres (3,200 mi).

s, all procellariids are exclusively marine

, and the diet of all species is dominated by either fish

, squid

, crustacean

s and carrion

, or some combination thereof.

The majority of species are surface feeders, obtaining food that has been pushed to the surface by other predators or currents, or have floated in death. Among the surface feeders some, principally the gadfly petrel

s, can obtain food by dipping from flight, while most of the rest feed while sitting on the water. These surface feeders are dependent on their prey being close to the surface, and for this reason procellariids are often found in association with other predators or oceanic convergences. Studies have shown strong associations between many different kinds of seabird

s, including Wedge-tailed Shearwater

s, and dolphin

s and tuna

, which push shoaling fish up towards the surface.

The fulmarine petrel

s are generalists which for the most part take many species of fish and crustacea. The giant petrels, uniquely for Procellariiformes, will feed on land, eating the carrion of other seabirds and seals

. They will also attack the chicks of other seabirds. The diet of the giant petrels varies according to sex

, with the females taking more krill

and the males more carrion. All the fulmarine petrels readily feed on fisheries discards at sea, a habit that has been implicated in (but not proved to have caused) the expansion in range of the Northern Fulmar in the Atlantic.

Three of the six prion

Three of the six prion

species have bills filled with lamellae

which act as filters to sift zooplankton

from the water. Water is forced through the lamellae and small prey items are collected. This technique is often used in conjunction with a method known as hydroplaning where the bird dips its bill beneath the surface and propels itself forward with wings and feet as if walking on the water.

Many of the shearwater

s in the genus Puffinus

are proficient divers. While it has long been known that they regularly dive from the surface to pursue prey, using both their wings and feet for propulsion, the depth that they are able to dive to was not appreciated (or anticipated) until scientists began to deploy maximum-depth recorders on foraging birds. Studies of both long-distance migrants such as the Sooty Shearwater

and more sedentary species such as the Black-vented Shearwater

have shown maximum diving depths of 67 m (219.8 ft) and 52 m (170.6 ft). Tropical shearwaters, such as the Wedge-tailed Shearwater and the Audubon's Shearwater

, also dive in order to hunt, making the shearwaters the only tropical seabirds capable of exploiting that ecological niche (all other tropical seabirds feed close to the surface). Many other species of procellariid, from White-chinned Petrel

s to Slender-billed Prion

s, dive to a couple of metres below the surface, though not as proficiently or as frequently as the shearwaters.

The procellariids are colonial, nesting for the most part on islands. These colonies vary in size from over a million birds to just a few pairs, and can be densely concentrated or widely spaced. At one extreme the Greater Shearwater nests in concentrations of 1 pair per square metre in three colonies of more than 1 million pairs, whereas the giant petrels nest in clumped but widely spaced territories that barely qualify as colonial. Colonies are usually located near the coast, but some species nest far inland and even at high altitudes (such as the Barau's Petrel

The procellariids are colonial, nesting for the most part on islands. These colonies vary in size from over a million birds to just a few pairs, and can be densely concentrated or widely spaced. At one extreme the Greater Shearwater nests in concentrations of 1 pair per square metre in three colonies of more than 1 million pairs, whereas the giant petrels nest in clumped but widely spaced territories that barely qualify as colonial. Colonies are usually located near the coast, but some species nest far inland and even at high altitudes (such as the Barau's Petrel

).

Most seabird

s are colonial, and the reasons for colonial behaviour are assumed to be similar, if incompletely understood by scientists. Procellariids for the most part have weak legs and are unable to easily take off, making them highly vulnerable to mammal

ian predators. Most procellariid colonies are located on islands that have historically been free of mammals; for this reason some species cannot help but be colonial as they are limited to a few locations to breed. Even species that breed on continental Antarctica, such as the Antarctic Petrel

, are forced by habitat preference (snow-free north-facing rock) to breed in just a few locations.

Most procellariids' nests are in burrows or on the surface on open ground, with a smaller number nesting under the cover of vegetation (such as in a forest). All the fulmarine petrels bar the Snow Petrel

nest in the open, the Snow Petrel instead nesting inside natural crevices. Of the rest of the procellariids the majority nest in burrows or crevices, with a few tropical species nesting in the open. There are several reasons for these differences. The fulmarine petrels are probably precluded from burrowing by their large size (the crevice-nesting Snow Petrel is the smallest fulmarine petrel) and the high latitudes they breed in, where frozen ground is difficult to burrow into. The smaller size of the other species, and their lack of agility on land, mean that even on islands free from mammal predators they are still vulnerable to skua

s, gull

s and other avian predators, something the aggressive oil

-spitting fulmar

s are not. The chicks of all species are vulnerable to predation, but the chicks of fulmarine petrels can defend themselves in a similar fashion to their parents. In the higher latitudes there are thermal advantages to burrow nesting, as the temperature is more stable than on the surface, and there is no wind-chill to contend with. The absence of skuas, gulls and other predatory birds on tropical islands is why some shearwater

s and two species of gadfly petrel

can nest in the open. This has the advantages of reducing competition with burrow nesters from other species and allowing open-ground nesters to nest on coral

line islets without soil for burrowing. Procellariids that burrow in order to avoid predation almost always attend their colonies nocturnally

in order to reduce predation as well. Of the ground-nesting species the majority attend their colonies during the day, the exception being the Herald Petrel

, which is thought to be vulnerable to the diurnal White-bellied Sea Eagle

.

Procellariids display high levels of philopatry

Procellariids display high levels of philopatry

, exhibiting both natal philopatry and site fidelity. Natal philopatry, the tendency of a bird to breed close to where it hatched, is strong amongst all the Procellariiformes. The evidence for natal philopatry comes from several sources, not the least of which is the existence of several procellariid species that are endemic to a single island. The study of mitochondrial DNA

also provides evidence of restricted gene flow

between different colonies, and has been used to show philopatry in Fairy Prion

s. Bird ringing

also provides compelling evidence of philopatry; a study of Cory's Shearwater

s nesting near Corsica

found that of nine out of 61 male chicks that returned to breed at their natal colony actually bred in the burrow they were raised in. This tendency towards philopatry is stronger in some species than others, and several species readily prospect potential new colony sites and colonise them. It is hypothesised that there is a cost to dispersing to a new site, the chance of not finding a mate of the same species, that selects against it for rarer species, whereas there is probably an advantage to dispersal for species which have colony sites that change dramatically during periods of glacial advance or retreat

. There are also differences in the tendency to disperse based on sex, with females being more likely to breed away from the natal site.

s. The strength of this fidelity can also vary with sex; almost 85% of male Cory's Shearwater

s return to the same burrow to breed the year after a successful breeding attempt, while the figure for females is around 76%. This tendency towards using the same site from year to year is matched by strong mate fidelity

, with birds breeding with the same partner for many years; in fact it is suggested that the two are linked, site fidelity being a means by which partnered birds could meet at the beginning of the breeding season. One pair of Northern Fulmar

s bred as a pair in the same site for 25 years. Like the albatross

es the procellariids take several years to reach sexual maturity, though due to the greater variety of sizes and lifestyles, the age of first breeding stretches from just three years in the smaller species to 12 years in the larger ones.

The procellariids lack the elaborate breeding dances of the albatrosses, in no small part due to the tendency of most of them to attend colonies at night and breed in burrows, where visual displays are useless. The fulmarine petrel

The procellariids lack the elaborate breeding dances of the albatrosses, in no small part due to the tendency of most of them to attend colonies at night and breed in burrows, where visual displays are useless. The fulmarine petrel

s, which nest on the surface and attend their colonies diurnally, do use a repertoire of stereotyped behaviours

such as cackling, preening, head waving and nibbling, but for most species courtship interactions are limited to some billing (rubbing the two bills together) in the burrow and the vocalisations made by all species. The calls serve a number of functions: they are used territorially to protect burrows or territories and to call for mates. Each call type is unique to a particular species and indeed it is possible for procellariids to identify the sex of the bird calling as well. It may also be possible to assess the quality of potential mates; a study of Blue Petrel

s found a link between the rhythm

and duration of calls and the body mass of the bird. The ability of an individual to recognise its mate has also been demonstrated in several species.

, will skip a breeding season after successfully fledging

a chick, and some of the smaller species, such as the Christmas Shearwater

s, breed on a nine-month schedule. Amongst those that breed annually, there is considerable variation as to the timing; some species breed in a fixed season whilst others breed all year round. Climate

and the availability of food resources are important influences on the timing of procellariid breeding; species that breed at higher latitude

s always breed in the summer as conditions are too harsh in the winter. At lower latitudes many, but not all, species breed continuously. Some species breed seasonally, to avoid competition with other species for burrows, to avoid predation or to take advantage of seasonally abundant food. Others, such as the tropical Wedge-tailed Shearwater

, breed seasonally for reasons unknown. Among the species that exhibit seasonal breeding there can be high levels of synchronization, both of time of arrival at the colony and of lay date.

Procellariids begin to attend their nesting colony around one month prior to laying. Males will arrive first and attend the colony more frequently than females, partly in order to protect a site or burrow from potential competitors. Prior to laying there is a period known as the pre-laying exodus in which both the male and female are away from the colony, building up reserves in order to lay and undertake the first incubation stint respectively. This pre-laying exodus can vary in length from 9 days (as in the Cape Petrel

) to around 50 days in Atlantic Petrel

s. All procellariids lay one egg

per pair per breeding season, in common with the rest of the Procellariiformes. The egg is large compared to that of other birds, weighing 6–24% of the female's weight. Immediately after laying the female goes back to sea to feed while the male takes over incubation. Incubation duties are shared by both sexes in shifts that vary in length between species, individuals and even the stage of incubation. The longest recorded shift was 29 days by a Murphy's Petrel

from Henderson Island

; the typical length of a gadfly petrel

stint is between 13 and 19 days. Fulmarine petrel

s, shearwater

s and prions

tend to have shorter stints, averaging between 3 to 13 days. Incubation takes a long time, from 40 days for the smaller species (such as prions) to around 55 days for the larger species. The incubation period is longer if eggs are abandoned temporarily; procellariid eggs are resistant to chilling and can still hatch after being left unattended for a few days.

After hatching the chick is brooded by a parent until it is large enough to thermoregulate

After hatching the chick is brooded by a parent until it is large enough to thermoregulate

efficiently, and in some cases defend itself from predation. This guard stage lasts a short while for burrow-nesting species (2–3 days) but longer for surface nesting fulmar

s (around 16–20 days) and giant petrel

s (20–30 days). After the guard stage both parents feed the chick. In many species the parent's foraging strategy alternates between short trips lasting 1–3 days and longer trips of 5 days. The shorter trips, which are taken over the continental shelf, benefit the chick with faster growth, but longer trips to more productive pelagic

feeding grounds are needed for the parents to maintain their own body condition. The meals are composed of both prey items and stomach oil

, an energy

-rich food that is lighter to carry than undigested prey items. This oil is created in a stomach organ known as a proventriculus from digested prey items, and gives procellariids and other Procellariifromes their distinctive musty smell. Chick development is quite slow for bird

s, with fledging

taking place at around 2 months after hatching for the smaller species and 4 months for the largest species. The chicks of some species are abandoned by the parents; parents of other species continue to bring food to the nesting site after the chick has left. Chicks put on weight quickly and some can outweigh their parents; although, they will slim down before they leave the nest. All procellariid chicks fledge by themselves, and there is no further parental care after fledging. Life expectancy of Procellariidae is between 15 and 20 years; although, the oldest recorded member was a Northern Fulmar

that was over 50 years.

Procellariids have been a seasonally abundant source of food for people wherever people have been able to reach their colonies. Early records of human exploitation of shearwaters (along with albatross

Procellariids have been a seasonally abundant source of food for people wherever people have been able to reach their colonies. Early records of human exploitation of shearwaters (along with albatross

es and cormorant

s) come from the remains of hunter-gatherer

midden

s in southern Chile

, where Sooty Shearwater

s were taken 5000 years ago. More recently procellariids have been hunted for food by Europeans, particularly the Northern Fulmar

in Europe, and various species by eskimo

s, and sailors around the world. The hunting pressure on the Bermuda Petrel

, or Cahow, was so intense that the species nearly went extinct and did go missing for 300 years. The name of one species, the Providence Petrel

, is derived from its (seemingly) miraculous arrival on Norfolk Island

, where it provided a windfall for starving European settlers; within ten years the Providence Petrel was extinct on Norfolk. Several species of procellariid have gone extinct in the Pacific since the arrival of man, and their remains have been found in middens dated to that time. More sustainable shearwater harvesting industries developed in Tasmania

and New Zealand

, where the practice of harvesting what are known as muttonbird

s continues today.

. Human activities have caused dramatic declines in the numbers of some species, particularly species that were originally restricted to one island. According to the IUCN 36 species are listed as vulnerable or worse, with ten critically endangered. Procellariids are threatened by introduced species

on their breeding grounds, marine fisheries, pollution

, exploitation and possibly by climate change

.

The most pressing threat for many species, particularly the smaller ones, comes from species introduced to their colonies. Procellariids overwhelmingly breed on islands away from land predators such as mammals, and for the most part have lost the defensive adaptations needed to deal with them (with the exception of the oil

-spitting fulmarine petrel

s). The introduction of mammal predators such as feral cat

s, rat

s, mongoose

s and even mice

can have disastrous results for ecologically naïve

seabird

s. These predators can either directly attack and kill breeding adults, or, more commonly, attack eggs and chicks. Burrowing species that leave their young unattended at a very early stage are particularly vulnerable to attack. Studies on Grey-faced Petrels breeding on New Zealand's Whale Island

(Moutohora) have shown that a population under heavy pressure from Norway Rats will produce virtually no young during a breeding season, whereas if the rats are controlled (through the use of poison), breeding success is much higher. That study also highlighted the role that non-predatory introduced species can play in harming seabirds; introduced rabbit

s on the island caused little damage to the petrels, other than damaging their burrows, but they also acted as a food source for the rats during the non-breeding season, which allowed rat numbers to be higher than they otherwise would be, resulting in more predators for the petrels to contend with. Interactions with introduced species can be quite complex. Gould's Petrel

s breed only on two islands, Cabbage Tree Island

and Boondelbah Island

off Port Stephens, New South Wales. Introduced rabbits destroyed the forest understory on Cabbage Tree Island; this both increased the vulnerability of the petrels to natural predators and left them vulnerable to the sticky fruits of the birdlime tree (Pisonia umbellifera

), a native plant. In the natural state these fruits lodge in the understory of the forest, but with the understorey removed the fruits fall to the ground where the petrels move about, sticking to their feathers and making flight impossible.

Larger species of procellariid face similar problems to the albatross

Larger species of procellariid face similar problems to the albatross

es with long-line fisheries

. These species readily take offal from fishing boats and will also steal bait from the long lines as they are being set, risking becoming snared on the hooks and drowning. In the case of the Spectacled Petrel

this has led to the species undergoing a large decline and its listing as critically endangered. Diving species, most especially the shearwaters, are also vulnerable to gillnet

fisheries. Studies of gill-net fisheries show that shearwaters (Sooty and Short-tailed) compose 60% of the seabirds killed by gill-nets in Japanese waters and 40% in Monterey Bay, California in the 1980s, with the total number of shearwaters killed in Japan being between 65,000 and 125,000 per annum over the same study period (1978–1981).

Procellariids are vulnerable to other threats as well. Ingestion of plastic flotsam is a problem for the family as it is for many other seabirds. Once swallowed, this plastic can cause a general decline in the fitness of the bird, or in some cases lodge in the gut and cause a blockage, leading to death by starvation. Procellariids are also vulnerable to general marine pollution, as well as oil spills. Some species, such as the Barau's Petrel

, the Newell's Shearwater

or the Cory's Shearwater

, which nest high up on large developed islands are victims of light pollution. Chicks that are fledging

are attracted to streetlights and are unable to reach the sea. An estimated 20–40% of fledging Barau's Petrels are attracted to the streetlights on Réunion

.

Conservationists are working with governments and fisheries in order to prevent further declines and increase populations of endangered procellariids. Progress has been made in protecting many colonies where most species are most vulnerable. On 20 June 2001, the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels

was signed by seven major fishing nations. The agreement lays out a plan to manage fisheries by-catch, protect breeding sites, promote conservation in the industry, and research threatened species. The developing field of island restoration

, where introduced species are removed and native species and habitats restored, has been used in several procellariid recovery programmes. Invasive species such as rats, feral cats and pigs have been either removed or controlled in many remote islands in the tropical Pacific (such as the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

), around New Zealand (where island restoration was developed), and in the south Atlantic and Indian Ocean

s. The Grey-faced Petrels of Whale Island (mentioned above) have been achieving much higher fledging successes after the introduced Norway Rats were finally completely removed. At sea, procellariids threatened by long-line fisheries can be protected using techniques such as setting long-line bait at night, dying the bait blue, setting the bait underwater, increasing the amount of weight on lines and using bird scarers can all reduce the seabird by-catch. A further step towards conservation has been the signing of the 2001 treaty

the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels

, which came into force in 2004 and has been ratified by eight countries, Australia

, Ecuador

, New Zealand

, Spain

, South Africa

, France

, Peru

and the United Kingdom

. The treaty requires these countries to take specific actions to reduce by-catch and pollution and to remove introduced species from nesting islands.

word procella which means a violent wind or a storm, and idae which is added to symbolize Family. Therefore a violent wind or a storm refers to the fact that members of this Family

like stormy and windy weather.

Family (biology)

In biological classification, family is* a taxonomic rank. Other well-known ranks are life, domain, kingdom, phylum, class, order, genus, and species, with family fitting between order and genus. As for the other well-known ranks, there is the option of an immediately lower rank, indicated by the...

Procellariidae is a group of seabird

Seabird

Seabirds are birds that have adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same environmental problems and feeding niches have resulted in similar adaptations...

s that comprises the fulmarine petrel

Fulmarine petrel

The fulmarine petrels or fulmar-petrels are a distinct group of petrels within the procellariidae family. They are the most variable of the four groups within the Procellariidae, differing greatly in size and biology. They do have, however, have a unifying feature, their skull, and in particular...

s, the gadfly petrel

Gadfly petrel

The gadfly petrels are seabirds in the bird order Procellariiformes. These medium to large petrels feed on food items picked from the ocean surface....

s, the prions

Prion (bird)

The Prions are small petrels in the genera Pachyptila and Halobaena. They form one of the four groups within the Procellariidae , along with the gadfly petrels, shearwaters and fulmarine petrels....

, and the shearwater

Shearwater

Shearwaters are medium-sized long-winged seabirds. There are more than 30 species of shearwaters, a few larger ones in the genus Calonectris and many smaller species in the genus Puffinus...

s. This family is part of the bird

Bird

Birds are feathered, winged, bipedal, endothermic , egg-laying, vertebrate animals. Around 10,000 living species and 188 families makes them the most speciose class of tetrapod vertebrates. They inhabit ecosystems across the globe, from the Arctic to the Antarctic. Extant birds range in size from...

order Procellariiformes

Procellariiformes

Procellariiformes is an order of seabirds that comprises four families: the albatrosses, petrels and shearwaters, storm petrels, and diving petrels...

(or tubenoses), which also includes the albatross

Albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds allied to the procellariids, storm-petrels and diving-petrels in the order Procellariiformes . They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pacific...

es, the storm-petrel

Storm-petrel

Storm petrels are seabirds in the family Hydrobatidae, part of the order Procellariiformes. These smallest of seabirds feed on planktonic crustaceans and small fish picked from the surface, typically while hovering. The flight is fluttering and sometimes bat-like.Storm petrels have a cosmopolitan...

s, and the diving petrel

Diving petrel

The diving petrels are seabirds in the bird order Procellariiformes. There are four very similar species all in the family Pelecanoididae and genus Pelecanoides , distinguished only by small differences in the coloration of their plumage and their bill construction.Diving petrels are auk-like small...

s.

The procellariids are the most numerous family of tubenoses, and the most diverse. They range in size from the giant petrel

Giant petrel

Giant petrels is a genus, Macronectes, from the family Procellariidae and consist of two species. They are the largest birds from this family...

s, which are almost as large as the albatrosses, to the prions, which are as small as the larger storm-petrels. They feed on fish

Fish

Fish are a paraphyletic group of organisms that consist of all gill-bearing aquatic vertebrate animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish, as well as various extinct related groups...

, squid

Squid

Squid are cephalopods of the order Teuthida, which comprises around 300 species. Like all other cephalopods, squid have a distinct head, bilateral symmetry, a mantle, and arms. Squid, like cuttlefish, have eight arms arranged in pairs and two, usually longer, tentacles...

and crustacea, with many also taking fisheries discards

Discards

Discards are the portion of a catch of fish which is not retained on board during commercial fishing operations and is returned, often dead or dying, to the sea...

and carrion

Carrion

Carrion refers to the carcass of a dead animal. Carrion is an important food source for large carnivores and omnivores in most ecosystems. Examples of carrion-eaters include vultures, hawks, eagles, hyenas, Virginia Opossum, Tasmanian Devils, coyotes, Komodo dragons, and burying beetles...

. All species are accomplished long-distance foragers, and many undertake long trans-equatorial

Equator

An equator is the intersection of a sphere's surface with the plane perpendicular to the sphere's axis of rotation and containing the sphere's center of mass....

migrations

Bird migration

Bird migration is the regular seasonal journey undertaken by many species of birds. Bird movements include those made in response to changes in food availability, habitat or weather. Sometimes, journeys are not termed "true migration" because they are irregular or in only one direction...

. They are colonial breeders, exhibiting long-term mate fidelity

Monogamy

Monogamy /Gr. μονός+γάμος - one+marriage/ a form of marriage in which an individual has only one spouse at any one time. In current usage monogamy often refers to having one sexual partner irrespective of marriage or reproduction...

and site philopatry

Philopatry

Broadly, philopatry is the behaviour of remaining in, or returning to, an individual's birthplace. More specifically, in ecology philopatry is the behaviour of elder offspring sharing the parental burden in the upbringing of their siblings, a classic example of kin selection...

. In all species, each pair lays a single egg

Egg (biology)

An egg is an organic vessel in which an embryo first begins to develop. In most birds, reptiles, insects, molluscs, fish, and monotremes, an egg is the zygote, resulting from fertilization of the ovum, which is expelled from the body and permitted to develop outside the body until the developing...

per breeding season. Their incubation times and chick-rearing periods are exceptionally long compared to other birds.

Many procellariids have breeding populations of over several million pairs; others number fewer than 200 birds. Humans have traditionally exploited several species of fulmar

Fulmar

Fulmars are seabirds of the family Procellariidae. The family consists of two extant species and two that are extinct.-Taxonomy:As members of Procellaridae and then the order Procellariiformes, they share certain traits. First, they have nasal passages that attach to the upper bill called...

and shearwater (known as muttonbird

Muttonbird

Muttonbird, mutton-bird or mutton bird refer to seabirds – particularly certain large shearwaters – whose young are collected for food and other uses before they fledge ....

s) for food, fuel, and bait, a practice that continues in a controlled fashion today. Several species are threatened by introduced species

Introduced species

An introduced species — or neozoon, alien, exotic, non-indigenous, or non-native species, or simply an introduction, is a species living outside its indigenous or native distributional range, and has arrived in an ecosystem or plant community by human activity, either deliberate or accidental...

attacking adults and chicks in breeding colonies and by long-line fisheries

Long-line fishing

Longline fishing is a commercial fishing technique. It uses a long line, called the main line, with baited hooks attached at intervals by means of branch lines called "snoods". A snood is a short length of line, attached to the main line using a clip or swivel, with the hook at the other end....

.

Taxonomy and evolution

According to the famous DNA hybridization study into avianBird

Birds are feathered, winged, bipedal, endothermic , egg-laying, vertebrate animals. Around 10,000 living species and 188 families makes them the most speciose class of tetrapod vertebrates. They inhabit ecosystems across the globe, from the Arctic to the Antarctic. Extant birds range in size from...

phylogenetic relationships by Sibley and Ahlquist

Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy

The Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy is a bird taxonomy proposed by Charles Sibley and Jon Edward Ahlquist. It is based on DNA-DNA hybridization studies conducted in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s....

, the split of the Procellariiformes

Procellariiformes

Procellariiformes is an order of seabirds that comprises four families: the albatrosses, petrels and shearwaters, storm petrels, and diving petrels...

into the four families occurred around 30 million years ago; a fossil

Fossil

Fossils are the preserved remains or traces of animals , plants, and other organisms from the remote past...

bone often attributed to the order, described as the genus Tytthostonyx

Tytthostonyx

Tytthostonyx is a genus of prehistoric seabird. Found in the much-debated Hornerstown Formation which straddles the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary 65 million years ago, this animal was apparently closely related to the ancestor of some modern birds, such as Procellariiformes and/or "Pelecaniformes"...

, has been found in rocks dating around the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary

Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, formerly named and still commonly referred to as the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event, occurred approximately 65.5 million years ago at the end of the Maastrichtian age of the Cretaceous period. It was a large-scale mass extinction of animal and plant...

(70-60 mya), but the remains are too incomplete for placement within the Procellariiformes to be certain.

The molecular evidence suggests that the storm-petrels were the first to diverge from the ancestral stock, and the albatrosses next, with the procellariids and diving petrels splitting most recently. Many taxonomists used to retain the diving petrel

Diving petrel

The diving petrels are seabirds in the bird order Procellariiformes. There are four very similar species all in the family Pelecanoididae and genus Pelecanoides , distinguished only by small differences in the coloration of their plumage and their bill construction.Diving petrels are auk-like small...

s in this family also, but today their distinctiveness is considered well supported.

However, modern procellariid genera began to appear possibly just as early as the proposed splitting of the family, with a Rupelian

Rupelian

The Rupelian is, in the geologic timescale, the older of two ages or the lower of two stages of the Oligocene epoch/series. It spans the time between and . It is preceded by the Priabonian stage and is followed by the Chattian stage....

(Early Oligocene

Oligocene

The Oligocene is a geologic epoch of the Paleogene Period and extends from about 34 million to 23 million years before the present . As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that define the period are well identified but the exact dates of the start and end of the period are slightly...

) fossil from Belgium

Belgium

Belgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

tentatively attributed to the shearwater genus Puffinus,

and most modern genera were established by the Miocene

Miocene

The Miocene is a geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about . The Miocene was named by Sir Charles Lyell. Its name comes from the Greek words and and means "less recent" because it has 18% fewer modern sea invertebrates than the Pliocene. The Miocene follows the Oligocene...

. Thus, a basal radiation of the Procellariiformes in the Eocene

Eocene

The Eocene Epoch, lasting from about 56 to 34 million years ago , is a major division of the geologic timescale and the second epoch of the Paleogene Period in the Cenozoic Era. The Eocene spans the time from the end of the Palaeocene Epoch to the beginning of the Oligocene Epoch. The start of the...

at least (as with many modern orders of birds) seems likely, especially given that significant anomalies in molecular evolution rates and patterns have been discovered in the entire family (see also Leach's Storm-petrel

Leach's Storm-petrel

The Leach's Storm Petrel or Leach's Petrel is a small seabird of the tubenose family. It is named after the British zoologist William Elford Leach....

), and molecular dates must be considered extremely tentative. Some genera (Argyrodyptes, Pterodromoides) are only known from fossils. Eopuffinus from the Late Paleocene is sometimes placed in the Procellariidae, but even its placement in the Procellariiformes is quite doubtful.

Sibley and Ahlquist's taxonomy has included all the members of the Procellariiformes inside the Procellariidae and that family in an enlarged Ciconiiformes

Ciconiiformes

Traditionally, the order Ciconiiformes has included a variety of large, long-legged wading birds with large bills: storks, herons, egrets, ibises, spoonbills, and several others. Ciconiiformes are known from the Late Eocene...

, but this change has not been widely accepted.

Fulmarine petrel

The fulmarine petrels or fulmar-petrels are a distinct group of petrels within the procellariidae family. They are the most variable of the four groups within the Procellariidae, differing greatly in size and biology. They do have, however, have a unifying feature, their skull, and in particular...

s, the gadfly petrel

Gadfly petrel

The gadfly petrels are seabirds in the bird order Procellariiformes. These medium to large petrels feed on food items picked from the ocean surface....

s, the prions

Prion (bird)

The Prions are small petrels in the genera Pachyptila and Halobaena. They form one of the four groups within the Procellariidae , along with the gadfly petrels, shearwaters and fulmarine petrels....

, and the shearwater

Shearwater

Shearwaters are medium-sized long-winged seabirds. There are more than 30 species of shearwaters, a few larger ones in the genus Calonectris and many smaller species in the genus Puffinus...

s.

- The fulmarine petrels include the largest procellariids, the giant petrelGiant petrelGiant petrels is a genus, Macronectes, from the family Procellariidae and consist of two species. They are the largest birds from this family...

s, as well as the two fulmarFulmarFulmars are seabirds of the family Procellariidae. The family consists of two extant species and two that are extinct.-Taxonomy:As members of Procellaridae and then the order Procellariiformes, they share certain traits. First, they have nasal passages that attach to the upper bill called...

species, the Snow PetrelSnow PetrelThe Snow Petrel is the only member of the genus Pagodroma. It is one of only three birds that breed exclusively in Antarctica and has been seen at the South Pole. It has the most southerly breeding distribution of any bird.-Taxonomy:...

, the Antarctic PetrelAntarctic PetrelThe Antarctic Petrel is a boldly marked dark brown and white petrel, found in Antarctica, most commonly in the Ross and Weddell seas. They eat Antarctic krill, fish, and small squid...

, and the Cape PetrelCape PetrelThe Cape Petrel also called Cape Pigeon or Pintado Petrel, is a common seabird of the Southern Ocean from the family Procellariidae. It is the only member of the genus Daption, and is allied to the fulmarine petrels, and the Giant Petrels. It is also sometimes known as the Cape Fulmar...

. The fulmarine petrels are a diverse group with differing habits and appearances, but are linked morphologicallyMorphology (biology)In biology, morphology is a branch of bioscience dealing with the study of the form and structure of organisms and their specific structural features....

by their skullSkullThe skull is a bony structure in the head of many animals that supports the structures of the face and forms a cavity for the brain.The skull is composed of two parts: the cranium and the mandible. A skull without a mandible is only a cranium. Animals that have skulls are called craniates...

features, particularly the long prominent nasal tubes.

- The gadfly petrels, so named due to their helter-skelter flight, are the 37 species in the genusGenusIn biology, a genus is a low-level taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms, which is an example of definition by genus and differentia...

Pterodroma and have traditionally included the two species in the genus BulweriaBulweriaBulweria is a genus of seabirds in the family Procellariidae named after English naturalist James Bulwer. The genus has two living species, Bulwer's Petrel and Jouanin's Petrel...

. The species vary from small to medium sizes, 26 –, and are long winged with short hooked bills. The genus Pterodroma is now split into four sub genera, and some species have been split out of the genus (see below).

- The prions comprise six species of true prion in the genus PachyptilaPachyptilaPachyptila is a genus from the family Procellariidae and the Procellariiformes order. The members of this genus and the Blue Petrel form a sub-group called Prions.-Etymology:...

and the closely related Blue PetrelBlue PetrelThe Blue Petrel is a small seabird in the family Procellariidae. This small petrel is the only member of the genus Halobaena but is closely allied to the prions.-Taxonomy:...

. Often known in the past as whalebirds, three species have large bills filled with lamellaeLamellae (zoology)thumb|Lamellae on a gecko's foot.A lamella is a thin plate-like structure, often one amongst many lamellae very close to one another, with open space between...

that they use to filter planktonPlanktonPlankton are any drifting organisms that inhabit the pelagic zone of oceans, seas, or bodies of fresh water. That is, plankton are defined by their ecological niche rather than phylogenetic or taxonomic classification...

somewhat as baleen whaleBaleen whaleThe Baleen whales, also called whalebone whales or great whales, form the Mysticeti, one of two suborders of the Cetacea . Baleen whales are characterized by having baleen plates for filtering food from water, rather than having teeth. This distinguishes them from the other suborder of cetaceans,...

s do, though the old name derives from their association with whales, not their bills (though "prions" does, deriving from Ancient GreekAncient GreekAncient Greek is the stage of the Greek language in the periods spanning the times c. 9th–6th centuries BC, , c. 5th–4th centuries BC , and the c. 3rd century BC – 6th century AD of ancient Greece and the ancient world; being predated in the 2nd millennium BC by Mycenaean Greek...

for "sawSawA saw is a tool that uses a hard blade or wire with an abrasive edge to cut through softer materials. The cutting edge of a saw is either a serrated blade or an abrasive...

"). They are small procellariids, 25 –, with grey, patterned plumage, all inhabiting the Southern OceanSouthern OceanThe Southern Ocean comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60°S latitude and encircling Antarctica. It is usually regarded as the fourth-largest of the five principal oceanic divisions...

.

- The shearwaters are adapted for diving after prey instead of foraging on the ocean's surface; one species has been recorded diving as deep as 70 m (229.7 ft). The shearwaters are also well known for the long trans-equatorial migrations undertaken by many species. The shearwaters include the 20 or so species of the genus PuffinusPuffinusPuffinus is a genus of seabirds in the order Procellariiformes. It comprises about 20 small to medium-sized shearwaters. There are two other shearwater genera: Calonectris, which comprises three large shearwaters, and Procellaria with another four large species...

, as well as the five large ProcellariaProcellariaProcellaria is a genus of southern ocean long-winged seabirds related to prions and a member of the Procellariiformes order.-Taxonomy:Procellaria is a member of the family Procellariidae and the order procellariiformes. As members of Procellariiformes, they share certain characteristics. First they...

species and the three CalonectrisCalonectrisCalonectris is a genus of seabirds. It comprises three large shearwaters. There are two other shearwater genera. Puffinus, which comprises about twenty small to medium-sized shearwaters, and Procellaria with another four large species...

species. While all these three genera are known collectively as shearwaters, the Procellaria are called petrels in their common names. A recent study splits the shearwater genus Puffinus into two separate clades or subgroups, Puffinus and Neonectris. Puffinus are the 'smaller' Puffinus shearwaters (ManxManx ShearwaterThe Manx Shearwater is a medium-sized shearwater in the seabird family Procellariidae. The scientific name of this species records a name shift: Manx Shearwaters were called Manks Puffins in the 17th century. Puffin is an Anglo-Norman word for the cured carcasses of nestling shearwaters...

, LittleLittle ShearwaterThe Little Shearwater is a small shearwater in the seabird family Procellariidae.mtDNA cytochrome b sequence data indicates that the former North Atlantic Little Shearwater group is closer to Audubon's Shearwater , and myrtae being closer to the Newell's and possibly Townsend's Shearwater...

and Audubon's ShearwaterAudubon's ShearwaterAudubon's Shearwater, Puffinus lherminieri, is a common tropical seabird from the family Procellariidae. Sometimes called Dusky-backed Shearwater, the scientific name of this species commemorates the French naturalist Félix Louis L'Herminier....

s, for example), and the Neonectris are the 'larger' Puffinus shearwaters (Sooty ShearwaterSooty ShearwaterThe Sooty Shearwater is a medium-large shearwater in the seabird family Procellariidae. In New Zealand it is also known by its Māori name tītī and as "muttonbird", like its relatives the Wedge-tailed Shearwater and the Australian Short-tailed Shearwater The Sooty Shearwater (Puffinus griseus) is...

s, for example); in 2004 it was proposed that Neonectris be split into its own genus, Ardenna. This split into two clades is thought to have occurred soon after Puffinus split from the other procellariids, with the genus originating in the north Atlantic OceanAtlantic OceanThe Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

and the Neonectris clade evolving in the southern hemisphere.

However the two petrels in the genus Bulweria are no longer considered close to the gadfly petrels, instead being moved closer to the shearwaters in the genus Procellaria. Two genera, Pseudobulweria

Pseudobulweria

Pseudobulweria is a genus of seabirds in the family Procellariidae. They have long been retained with the gadfly petrel genus Pterodroma despite morphological differences. mtDNA cytochrome b sequence analysis has confirmed the split out of Pterodroma and places the genus closer to shearwaters...

and Lugensa, have been split from the gadfly petrel genus Pterodroma, with Pseudobulweria being phylogenetically closer to the Puffinus shearwaters than the Pterodroma gadfly petrels,

and Lugensa (the Kerguelen Petrel

Kerguelen Petrel

The Kerguelen Petrel is a small slate-grey seabird in the family Procellariidae. The species has been described as a "taxonomic oddball", being placed for a long time in Pterodroma before being split out in 1942 into its own genus Lugensa...

) possibly being closely related to the shearwaters or the fulmars.

The prions, according to Nunn and Stanley, were amongst the larger shearwater group. The Calonectris shearwaters were placed close to the two Puffinus clades (closer to the Puffinus, or small, clade) and both were distant to the Procellaria shearwaters. The relationships between the genera and within the genera are still the subject of debate, with researchers lumping and splitting

Lumpers and splitters

Lumping and splitting refers to a well-known problem in any discipline which has to place individual examples into rigorously defined categories. The lumper/splitter problem occurs when there is the need to create classifications and assign examples to them, for example schools of literature,...

the species and genera within the family and arguing about the position of the genera within the family. Many of the confusing species are amongst the least known of all seabirds; some of them (like the Fiji Petrel

Fiji Petrel

The Fiji Petrel , also known as MacGillivray's Petrel, is a small, dark gadfly petrel.The Fiji Petrel was originally known from one immature specimen found in 1855 on Gau Island, Fiji by naturalist John MacGillivray on board 'HMS Herald' who took the carcass to the British Museum in London...

) have not been seen more than 10 times since their discovery by science, and others' breeding grounds are unknown (like the Heinroth's Shearwater

Heinroth's Shearwater

Heinroth's Shearwater is a poorly known seabird in the family Procellariidae. Probably a close relative of the Little Shearwater or Audubon's Shearwater , it is distinguished by a long and slender bill and a brown-washed underside.This species is restricted to the seas around the Bismarck...

).

There are around 80 species

Species

In biology, a species is one of the basic units of biological classification and a taxonomic rank. A species is often defined as a group of organisms capable of interbreeding and producing fertile offspring. While in many cases this definition is adequate, more precise or differing measures are...

of procellariid in 14 genera

Genus

In biology, a genus is a low-level taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms, which is an example of definition by genus and differentia...

. For a complete list, and notes on different taxonomies, see List of Procellariidae.

Morphology and flight

The procellariids are small- to medium-sized seabirds. The largest, the giant petrelGiant petrel

Giant petrels is a genus, Macronectes, from the family Procellariidae and consist of two species. They are the largest birds from this family...

s with a wingspan of 81 to 99 cm (31.9 to 39 in), are almost as large as albatross

Albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds allied to the procellariids, storm-petrels and diving-petrels in the order Procellariiformes . They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pacific...

es; the smallest, such as the Fairy Prion

Fairy Prion

The Fairy Prion is a small seabird with the standard prion plumage of black upperparts and white underneath with an "M" wing marking.-Taxonomy:...

have a wingspan of 23 to 28 cm (9.1 to 11 in), are slightly bigger than the diving petrel

Diving petrel

The diving petrels are seabirds in the bird order Procellariiformes. There are four very similar species all in the family Pelecanoididae and genus Pelecanoides , distinguished only by small differences in the coloration of their plumage and their bill construction.Diving petrels are auk-like small...

s. There are no obvious differences between the sexes, although females tend to be slighter. Like all Procellariiformes, the procellariids have a characteristic tubular nasal passage which is used for olfaction. This ability to smell helps to locate patchily distributed prey at sea and may also help locate nesting colonies. The plumage

Plumage

Plumage refers both to the layer of feathers that cover a bird and the pattern, colour, and arrangement of those feathers. The pattern and colours of plumage vary between species and subspecies and can also vary between different age classes, sexes, and season. Within species there can also be a...

of the procellariids is usually dull, with greys, blues, blacks and browns being the usual colours, although some species have striking patterns (such as the Cape Petrel

Cape Petrel

The Cape Petrel also called Cape Pigeon or Pintado Petrel, is a common seabird of the Southern Ocean from the family Procellariidae. It is the only member of the genus Daption, and is allied to the fulmarine petrels, and the Giant Petrels. It is also sometimes known as the Cape Fulmar...

).

Bird flight

Flight is the main mode of locomotion used by most of the world's bird species. Flight assists birds while feeding, breeding and avoiding predators....

among procellariids depends on foraging methods. Compared to an average bird, all procellariids have a high aspect ratio

Aspect ratio

The aspect ratio of a shape is the ratio of its longer dimension to its shorter dimension. It may be applied to two characteristic dimensions of a three-dimensional shape, such as the ratio of the longest and shortest axis, or for symmetrical objects that are described by just two measurements,...

(meaning their wings are long and narrow) and a heavy wing loading

Wing loading

In aerodynamics, wing loading is the loaded weight of the aircraft divided by the area of the wing. The faster an aircraft flies, the more lift is produced by each unit area of wing, so a smaller wing can carry the same weight in level flight, operating at a higher wing loading. Correspondingly,...

. Therefore they must maintain a high speed in order to remain in the air. Most procellariids use two techniques to do this, namely, dynamic soaring

Dynamic soaring

Dynamic soaring is a flying technique used to gain energy by repeatedly crossing the boundary between air masses of significantly different velocity...

and slope soaring. Dynamic soaring involves gliding across wave fronts, thus taking advantage of the vertical wind gradient

Wind gradient

In common usage, wind gradient, more specifically wind speed gradientor wind velocity gradient,or alternatively shear wind,...

and minimising the effort required to stay in the air. Slope soaring is more straightforward: the procellariid turns to the wind, gaining height, from where it can then glide back down to the sea. Most procellariids aid their flight by means of flap-glides, where bursts of flapping are followed by a period of gliding; the amount of flapping dependent on the strength of the wind and the choppiness of the water. Shearwaters and other larger petrels, which have lower aspect ratio, must make more use of flapping to remain airborne than gadfly petrels. Because of the high speeds required for flight, procellariids need to either run or face into a strong wind in order to take off.

Tendon

A tendon is a tough band of fibrous connective tissue that usually connects muscle to bone and is capable of withstanding tension. Tendons are similar to ligaments and fasciae as they are all made of collagen except that ligaments join one bone to another bone, and fasciae connect muscles to other...

which locks the wing when fully extended, allowing the wing to be kept up and out without any muscle effort. Gadfly petrels often feed on the wing, snapping prey without landing on the water. The flight of the smaller prions is similar to that of the storm-petrel

Storm-petrel

Storm petrels are seabirds in the family Hydrobatidae, part of the order Procellariiformes. These smallest of seabirds feed on planktonic crustaceans and small fish picked from the surface, typically while hovering. The flight is fluttering and sometimes bat-like.Storm petrels have a cosmopolitan...

s, being highly erratic and involving weaving and even looping the loop. The wings of all species are long and stiff. In some species of shearwater the wings are also used to power the birds underwater while diving for prey. Their heavier wing loadings, in comparison with surface-feeding procellariids, allow these shearwaters to achieve considerable depths below 70 m (229.7 ft) in the case of the Short-tailed Shearwater

Short-tailed Shearwater

The Short-tailed Shearwater or Slender-billed Shearwater , also called Yolla or Moonbird, and commonly known as the muttonbird in Australia, is the most abundant seabird species in Australian waters, and is one of the few Australian native birds in which the chicks are commercially harvested...

).

Procellariids generally have weak legs which are set back, and many species move around on land by resting on the breast and pushing themselves forward, often with the help of their wings. The exception to this is the two species of giant petrel, which like the albatrosses, have strong legs used to feed on land (see below). The feet of shearwaters are set far back on the body for swimming and are of little use when on the ground.

Distribution and range at sea

The procellariids are present in all the world's oceans and most of the seas. They are absent from the Bay of BengalBay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal , the largest bay in the world, forms the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean. It resembles a triangle in shape, and is bordered mostly by the Eastern Coast of India, southern coast of Bangladesh and Sri Lanka to the west and Burma and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands to the...

and Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay , sometimes called Hudson's Bay, is a large body of saltwater in northeastern Canada. It drains a very large area, about , that includes parts of Ontario, Quebec, Saskatchewan, Alberta, most of Manitoba, southeastern Nunavut, as well as parts of North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota,...

, but are present year round or seasonally in the rest. The seas north of New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

are the centre of procellariid biodiversity

Biodiversity

Biodiversity is the degree of variation of life forms within a given ecosystem, biome, or an entire planet. Biodiversity is a measure of the health of ecosystems. Biodiversity is in part a function of climate. In terrestrial habitats, tropical regions are typically rich whereas polar regions...

, with the most species. Among the four groups, the fulmarine petrel

Fulmarine petrel

The fulmarine petrels or fulmar-petrels are a distinct group of petrels within the procellariidae family. They are the most variable of the four groups within the Procellariidae, differing greatly in size and biology. They do have, however, have a unifying feature, their skull, and in particular...

s have a mostly polar

Polar region

Earth's polar regions are the areas of the globe surrounding the poles also known as frigid zones. The North Pole and South Pole being the centers, these regions are dominated by the polar ice caps, resting respectively on the Arctic Ocean and the continent of Antarctica...

distribution, with most species living around Antarctica and one, the Northern Fulmar

Fulmar

Fulmars are seabirds of the family Procellariidae. The family consists of two extant species and two that are extinct.-Taxonomy:As members of Procellaridae and then the order Procellariiformes, they share certain traits. First, they have nasal passages that attach to the upper bill called...

ranging in the Northern Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The prion

Prion (bird)

The Prions are small petrels in the genera Pachyptila and Halobaena. They form one of the four groups within the Procellariidae , along with the gadfly petrels, shearwaters and fulmarine petrels....

s are restricted to the Southern Ocean

Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60°S latitude and encircling Antarctica. It is usually regarded as the fourth-largest of the five principal oceanic divisions...

, and the gadfly petrel

Gadfly petrel

The gadfly petrels are seabirds in the bird order Procellariiformes. These medium to large petrels feed on food items picked from the ocean surface....

s are found mostly in the tropics with some temperate species. The shearwater

Shearwater

Shearwaters are medium-sized long-winged seabirds. There are more than 30 species of shearwaters, a few larger ones in the genus Calonectris and many smaller species in the genus Puffinus...

s are the most widespread group and breed in most temperate and tropical seas, although by a biogeographical

Biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species , organisms, and ecosystems in space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities vary in a highly regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, isolation and habitat area...

quirk are absent as breeders from the North Pacific.

Bird migration

Bird migration is the regular seasonal journey undertaken by many species of birds. Bird movements include those made in response to changes in food availability, habitat or weather. Sometimes, journeys are not termed "true migration" because they are irregular or in only one direction...

in the non-breeding season. Southern species of shearwater such as the Sooty Shearwater

Sooty Shearwater

The Sooty Shearwater is a medium-large shearwater in the seabird family Procellariidae. In New Zealand it is also known by its Māori name tītī and as "muttonbird", like its relatives the Wedge-tailed Shearwater and the Australian Short-tailed Shearwater The Sooty Shearwater (Puffinus griseus) is...

and Short-tailed Shearwater

Short-tailed Shearwater

The Short-tailed Shearwater or Slender-billed Shearwater , also called Yolla or Moonbird, and commonly known as the muttonbird in Australia, is the most abundant seabird species in Australian waters, and is one of the few Australian native birds in which the chicks are commercially harvested...

, breeding on islands off Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

, New Zealand and Chile

Chile

Chile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

, undertake transequatorial migrations of millions of birds up to the waters off Alaska

Alaska

Alaska is the largest state in the United States by area. It is situated in the northwest extremity of the North American continent, with Canada to the east, the Arctic Ocean to the north, and the Pacific Ocean to the west and south, with Russia further west across the Bering Strait...

and back each year during the austral winter. Manx Shearwater

Manx Shearwater

The Manx Shearwater is a medium-sized shearwater in the seabird family Procellariidae. The scientific name of this species records a name shift: Manx Shearwaters were called Manks Puffins in the 17th century. Puffin is an Anglo-Norman word for the cured carcasses of nestling shearwaters...

s from the North Atlantic also undertake transequatorial migrations from Western Europe and North America to the waters off Brazil in the South Atlantic. The mechanisms of navigation

Navigation

Navigation is the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another. It is also the term of art used for the specialized knowledge used by navigators to perform navigation tasks...

are poorly understood, but displacement experiments where individuals were removed from colonies and flown to far-flung release sites have shown that they are able to home in on their colonies with remarkable precision. A Manx Shearwater released in Boston returned to its colony in Skomer

Skomer

Skomer is a 2.92 km² island off the coast of southwest Wales, one of a chain lying within a kilometre off the Pembrokeshire coast and separated from the mainland by the treacherous waters of Jack Sound....

, Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

within 13 days, a distance of 5,150 kilometres (3,200 mi).

Diet

The diet of the procellariids is the most diverse of all the Procellariiformes, as are the methods employed to obtain it. With the exception of the giant petrelGiant petrel

Giant petrels is a genus, Macronectes, from the family Procellariidae and consist of two species. They are the largest birds from this family...

s, all procellariids are exclusively marine

Ocean

An ocean is a major body of saline water, and a principal component of the hydrosphere. Approximately 71% of the Earth's surface is covered by ocean, a continuous body of water that is customarily divided into several principal oceans and smaller seas.More than half of this area is over 3,000...

, and the diet of all species is dominated by either fish

Fish

Fish are a paraphyletic group of organisms that consist of all gill-bearing aquatic vertebrate animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish, as well as various extinct related groups...

, squid

Squid

Squid are cephalopods of the order Teuthida, which comprises around 300 species. Like all other cephalopods, squid have a distinct head, bilateral symmetry, a mantle, and arms. Squid, like cuttlefish, have eight arms arranged in pairs and two, usually longer, tentacles...

, crustacean

Crustacean

Crustaceans form a very large group of arthropods, usually treated as a subphylum, which includes such familiar animals as crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, krill and barnacles. The 50,000 described species range in size from Stygotantulus stocki at , to the Japanese spider crab with a leg span...

s and carrion

Carrion

Carrion refers to the carcass of a dead animal. Carrion is an important food source for large carnivores and omnivores in most ecosystems. Examples of carrion-eaters include vultures, hawks, eagles, hyenas, Virginia Opossum, Tasmanian Devils, coyotes, Komodo dragons, and burying beetles...

, or some combination thereof.

The majority of species are surface feeders, obtaining food that has been pushed to the surface by other predators or currents, or have floated in death. Among the surface feeders some, principally the gadfly petrel

Gadfly petrel

The gadfly petrels are seabirds in the bird order Procellariiformes. These medium to large petrels feed on food items picked from the ocean surface....

s, can obtain food by dipping from flight, while most of the rest feed while sitting on the water. These surface feeders are dependent on their prey being close to the surface, and for this reason procellariids are often found in association with other predators or oceanic convergences. Studies have shown strong associations between many different kinds of seabird

Seabird

Seabirds are birds that have adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same environmental problems and feeding niches have resulted in similar adaptations...