Religion in Sudan

Encyclopedia

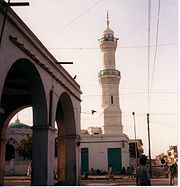

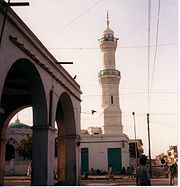

Religion plays an important role in Sudan

, with most of the country's population adhering to Islam

, Animism

, or Christianity

. More than half Sudan's population was Muslim in the early 1990s. Most Muslims (ca 90 %), lived in the north, where they constituted ca 85% percent or more of the population. The World Christian Encyclopaedia provides an estimate of the Christian population in 2000 of 16.7%. Most Christian Sudanese and adherents of local religious systems lived in southern Sudan. Islam had made inroads into the south, but more through the need to know Arabic than a profound belief in the tenets of the Quran. The SPLM, which in 1991 controlled most of southern Sudan, opposed the imposition of the Sharia

(Islamic law). Christianity has grown from about 5% of the southerners to 50-70% today. with most of the rest still attached to the indigenous religions of their forebears.

Both Darfur

and Northern Sudan are mostly Muslim, whereas the South is Animist and Christian.

branch of Islam; recently a growing number of Shias have emerged in Khartoum and surrounding villages. Sunni Islam in Sudan is not marked by a uniform body of belief and practice, however. Some Muslims opposed aspects of Sunni orthodoxy, and rites having a non-Islamic origin were widespread, being accepted as if they were integral to Islam, or sometimes being recognized as separate. Moreover, Sunni Islam in Sudan (as in much of Africa) has been characterized by the formation of religious orders or brotherhoods, each of which made special demands on its adherents.

Sunni Islam requires of the faithful five fundamental obligations that constitute the Five Pillars of Islam

Sunni Islam requires of the faithful five fundamental obligations that constitute the Five Pillars of Islam

. The first pillar, the shahadah or profession of faith is the affirmation "There is no god but God (Allah) and Muhammad

is his prophet." It is the first step in becoming a Muslim and a significant part of prayer. The second obligation is prayer at five specified times of the day

. The third enjoins almsgiving

. The fourth requires fasting during daylight hours

in the month of Ramadan

. The fifth requires a pilgrimage

to Mecca

for those able to perform it, to participate in the special rites that occur during the twelfth month of the lunar calendar

.

Most Sudanese Muslims are born to the faith and meet the first requirement. Conformity to the second requirement is more variable. Many males in the cities and larger towns manage to pray five times a day: at dawn, noon, midafternoon, sundown, and evening. The well-to-do perform little work during Ramadan, and many businesses close or operate on reduced schedules. In the early 1990s, its observance appeared to be widespread, especially in urban areas and among sedentary Sudanese Muslims.

The pilgrimage

The pilgrimage

to Mecca is less costly and arduous for the Sudanese than it is for many Muslims. Nevertheless, it takes time (or money if travel is by air), and the ordinary Sudanese Muslim has generally found it difficult to accomplish, rarely undertaking it before middle age. Some have joined pilgrimage societies into which members pay a small amount monthly and choose one of their number when sufficient funds have accumulated to send someone on the pilgrimage. A returned pilgrim is entitled to use the honorific title hajj or hajjih for a woman.

Another ceremony commonly observed is the great feast Id al Adha

(also known as Id al Kabir), representing the sacrifice made during the last days of the pilgrimage. The centerpiece of the day is the slaughter of a sheep, which is distributed to the poor, kin, neighbors, and friends, as well as the immediate family.

Islam imposes a standard of conduct encouraging generosity, fairness, and honesty towards other Muslims. Sudanese Arabs, especially those who are wealthy, are expected by their coreligionists to be generous.

. Conformity to the prohibitions on gambling and alcohol is less widespread. Usury

is also forbidden by Islamic law, but Islamic banks

have developed other ways of making money available to the public.

In Sudan (until 1983) modern criminal and civil, including commercial, law generally prevailed. In the north, however, the sharia, was expected to govern what is usually called family and personal law, i.e., matters such as marriage, divorce, and inheritance. In the towns and in some sedentary communities sharia was accepted, but in other sedentary communities and among nomads local custom was likely to prevail particularly with respect to inheritance.

In September 1983, Nimeiri

imposed the sharia throughout the land, eliminating the civil and penal codes by which the country had been governed in the twentieth century. Traditional Islamic punishments were imposed for theft, adultery, homicide

, and other crimes. The zealousness with which these punishments were carried out contributed to the fall of Nimeiri. Nevertheless, no successor government has shown inclination to abandon the sharia.

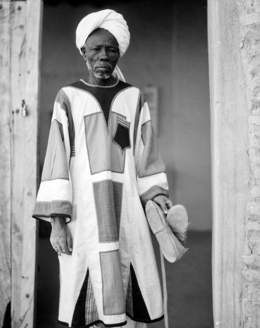

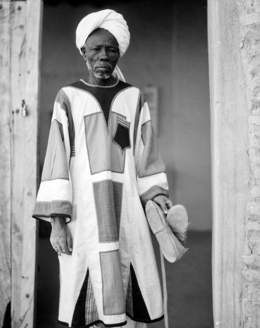

s as sources of illness or other afflictions and in magical ways of dealing with them. The imam

of a mosque is a prayer leader and preacher of sermons. He may also be a teacher and in smaller communities combines both functions. In the latter role, he is called a faqih

(pl., fuqaha), although a faqih need not be an imam. In addition to teaching in the local Qur'anic school (khalwa), the faqih is expected to write texts (from the Qur'an) or magical verses to be used as amulets and cures. His blessing may be asked at births, marriages, deaths, and other important occasions, and he may participate in wholly non-Islamic harvest rites in some remote places. All of these functions and capacities make the faqih the most important figure in popular Islam. But he is not a priest. His religious authority is based on his putative knowledge of the Qur'an, the sharia, and techniques for dealing with occult

threats to health and well- being. The notion that the words of the Qur'an will protect against the actions of evil spirits

or the evil eye

is deeply embedded in popular Islam, and the amulets prepared by the faqih are intended to protect their wearers against these dangers.

In Sudan as in much of African Islam, the cult of the saint

is of considerable importance, although some Muslims would reject it. The development of the cult is closely related to the presence of the religious orders; many who came to be considered saints on their deaths were founders or leaders of religious orders who in their lifetimes were thought to have barakah

, a state of blessedness implying an indwelling spiritual power inherent in the religious office. Baraka intensifies after death as the deceased becomes a wali

(literally friend of God, but in this context translated as saint). The tomb and other places associated with the saintly being become the loci of the person's baraka, and in some views he or she becomes the guardian spirit of the locality. The intercession of the wali is sought on a variety of occasions, particularly by those seeking cures or by barren women desiring children. A saint's annual holy day is the occasion of a local festival that may attract a large gathering.

Better-educated Muslims in Sudan may participate in prayer at a saint's tomb but argue that prayer is directed only to God. Many others, however, see the saint not merely as an intercessor with and an agent of God, but also as a nearly autonomous source of blessing and power, thereby approaching "popular" as opposed to orthodox Islam.

, a reaction based in mysticism

to the strongly legalistic orientation of mainstream Islam. These orders first came to Sudan in the sixteenth century and became significant in the eighteenth. Sufism seeks for its adherents a closer personal relationship with God through special spiritual disciplines. The exercises (or dhikr

) include reciting prayers and passages of the Qur'an and repeating the names, or attributes, of God while performing physical movements according to the formula established by the founder of the particular order. Singing and dancing may be introduced. The outcome of an exercise, which lasts much longer than the usual daily prayer, is often a state of ecstatic abandon.

A mystical or devotional way (sing. tariqa; pl. turuq) is the basis for the formation of particular orders, each of which is also called a tariqa. The specialists in religious law

and learning initially looked askance at Sufism and the Sufi orders, but the leaders of Sufi orders in Sudan have won acceptance by acknowledging the significance of the sharia and not claiming that Sufism replaces it.

The principal turuq vary considerably in their practice and internal organization. Some orders are tightly organized in hierarchical fashion; others have allowed their local branches considerable autonomy. There may be as many as a dozen turuq in Sudan. Some are restricted to that country; others are widespread in Africa

or the Middle East

. Several turuq, for all practical purposes independent, are offshoots of older orders and were established by men who altered in major or minor ways the tariqa of the orders to which they had formerly been attached.

The oldest and most widespread of the turuq is the Qadiriyah founded by Abdul Qadir Jilani in Baghdad

in the twelfth century and introduced into Sudan in the sixteenth. The Qadiriyah's principal rival and the largest tariqa in the western part of the country was the Tijaniyah, a sect begun by Sidi Ahmed al-Tidjani

at Tijani in Morocco

, which eventually penetrated Sudan in about 1810 via the western Sahel

(a narrow band of savanna bordering the southern Sahara, stretching across Africa). Many Tijani became influential in Darfur

, and other adherents settled in northern Kurdufan

. Later on, a class of Tijani merchants arose as markets grew in towns and trade expanded, making them less concerned with providing religious leadership. Of greater importance to Sudan was the tariqa established by the followers of Sayyid Ahmad ibn Idris

, known as Al Fasi

, who died in 1837. Although he lived in Arabia and never visited Sudan, his students spread into the Nile Valley establishing indigenous Sudanese orders which include the Majdhubiyah, the Idrisiyah, the Ismailiyah, and the Khatmiyyah.

Much different in organization from the other brotherhoods is the Khatmiyyah (or Mirghaniyah after the name of the order's founder). Established in the early nineteenth century by Muhammad Uthman al Mirghani, it became the best organized and most politically oriented and powerful of the turuq in eastern Sudan (see Turkiyah

). Mirghani had been a student of Sayyid Ahmad ibn Idris and had joined several important orders, calling his own order the seal of the paths (Khatim at Turuq—hence Khatmiyyah). The salient features of the Khatmiyyah are the extraordinary status of the Mirghani family, whose members alone may head the order; loyalty to the order, which guarantees paradise; and the centralized control of the order's branches.

The Khatmiyyah had its center in the southern section of Ash Sharqi State and its greatest following in eastern Sudan and in portions of the riverine area. The Mirghani family were able to turn the Khatmiyyah into a political power base, despite its broad geographical distribution, because of the tight control they exercised over their followers. Moreover, gifts from followers over the years have given the family and the order the wealth to organize politically. This power did not equal, however, that of the Mirghanis' principal rival, the Ansar

The Khatmiyyah had its center in the southern section of Ash Sharqi State and its greatest following in eastern Sudan and in portions of the riverine area. The Mirghani family were able to turn the Khatmiyyah into a political power base, despite its broad geographical distribution, because of the tight control they exercised over their followers. Moreover, gifts from followers over the years have given the family and the order the wealth to organize politically. This power did not equal, however, that of the Mirghanis' principal rival, the Ansar

, or followers of the Mahdi, whose present-day leader was Sadiq al-Mahdi

, the great-grandson of Muhammad Ahmad

, who drove the Egyptian administration from Sudan in 1885.

Most other orders were either smaller or less well organized than the Khatmiyyah. Moreover, unlike many other African Muslims, Sudanese Muslims did not all seem to feel the need to identify with one or another tariqa, even if the affiliation were nominal. Many Sudanese Muslims preferred more political movements that sought to change Islamic society and governance to conform to their own visions of the true nature of Islam.

One of these movements, Mahdism, was founded in the late nineteenth century. It has been likened to a religious order, but it is not a tariqa in the traditional sense. Mahdism and its adherents, the Ansar, sought the regeneration of Islam, and in general were critical of the turuq. Muhammad Ahmad ibn as Sayyid Abd Allah, a faqih, proclaimed himself to be al-Mahdi al-Muntazar

One of these movements, Mahdism, was founded in the late nineteenth century. It has been likened to a religious order, but it is not a tariqa in the traditional sense. Mahdism and its adherents, the Ansar, sought the regeneration of Islam, and in general were critical of the turuq. Muhammad Ahmad ibn as Sayyid Abd Allah, a faqih, proclaimed himself to be al-Mahdi al-Muntazar

("the awaited guide in the right path"), the messenger of God and representative of the Prophet Muhammad, an assertion that became an article of faith

among the Ansar. He was sent, he said, to prepare the way for the second coming

of the Prophet Isa

(Jesus) and the impending end of the world. In anticipation of Judgment Day, it was essential that the people return to a simple and rigorous, even puritanical Islam (see Mahdiyah). The idea of the coming of a Mahdi has roots in Sunni Islamic traditions. The issue for Sudanese and other Muslims was whether Muhammad Ahmad was in fact the Mahdi.

In the century since the Mahdist uprising, the neo-Mahdist movement and the Ansar, supporters of Mahdism from the west, have persisted as a political force in Sudan. Many groups, from the Baqqara

cattle nomads to the largely sedentary tribes on the White Nile

, supported this movement. The Ansar were hierarchically organized under the control of Muhammad Ahmad's successors, who have all been members of the Mahdi family (known as the ashraf

). The ambitions and varying political perspectives of different members of the family have led to internal conflicts, and it appeared that Sadiq al-Mahdi, putative leader of the Ansar since the early 1970s, did not enjoy the unanimous support of all Mahdists. Mahdist family political goals and ambitions seemed to have taken precedence over the movement's original religious mission. The modern-day Ansar were thus loyal more to the political descendants of the Mahdi than to the religious message of Mahdism.

A movement that spread widely in Sudan in the 1960s, responding to the efforts to secularize Islamic society, was the Muslim Brotherhood

(Al Ikhwan al Muslimin). Originally the Muslim Brotherhood, often known simply as the Brotherhood, was conceived as a religious revivalist movement that sought to return to the fundamentals of Islam in a way that would be compatible with the technological innovations introduced from the West. Disciplined, highly motivated, and well financed the Brotherhood became a powerful political force during the 1970s and 1980s, although it represented only a small minority of Sudanese. In the government that was formed in June 1989, following a bloodless coup d'état, the Brotherhood exerted influence through its political wing, the National Islamic Front

(NIF) party, which included several cabinet members among its adherents.

Christianity is most prevalent among the inhabitants of the states of Equatoria

Christianity is most prevalent among the inhabitants of the states of Equatoria

: the Madi, Moru

, Azande

, and Bari

. The major churches in the Sudan are the Roman Catholic, the Anglican (represented by the Episcopal Church of the Sudan

) and the Presbyterian. The Dinka people, the largest of the Nilotic tribes is largely Anglican, and the Nuer, the second largest, Presbyterian. The Coptic Orthodox Church's influence is also still present in Sudan. Southern Sudanese communities might include a few Christians, but the rituals and world view of this part of Sudan are dissimilar to those of Western Christianity

. The few communities that had formed around Western missions had disappeared with the dissolution of the missions in 1964.

The indigenous Christian churches in Sudan, with external support, continue their mission, however, and have opened new churches and repaired those destroyed in the continuing civil conflict. Originally the Nilotic

peoples were indifferent to Christianity, but in the latter half of the twentieth century many people in the educated elite embraced its tenets, at least superficially. English and Christianity have become symbols of resistance to the Muslim government in the north, which has vowed to destroy both. Unlike the early civil strife of the 1960s and 1970s, the insurgency in the 1980s and the 1990s has taken on a religious character.

or part of a group, although several groups may share elements of belief and ritual because of common ancestry or mutual influence. The group serves as the congregation, and an individual usually belongs to that faith by virtue of membership in the group. Believing and acting in a religious mode is part of daily life and is linked to the social, political, and economic actions and relationships of the group. The beliefs and practices of indigenous religions in Sudan are not systematized, in that the people do not generally attempt to put together in coherent fashion the doctrines they hold and the rituals they practice.

The concept of a high spirit or divinity, usually seen as a creator and sometimes as ultimately responsible for the actions of lesser spirits, is common to most Sudanese groups. Often the higher divinity is remote, and believers treat the other spirits as autonomous, orienting their rituals to these spirits rather than to the high god. Such spirits may be perceived as forces of nature or as manifestations of ancestors. Spirits may intervene in people's lives, either because individuals or groups have transgressed the norms of the society or because they have failed to pay adequate attention to the ritual that should be addressed to the spirits.

The Nilotes acknowledge an active supreme deity, who is therefore the object of ritual, but the beliefs and rituals differ from group to group. The Nuer, for example, have no word corresponding solely and exclusively to God. The word sometimes so translated refers not only to the universal governing spirit but also to ancestors and forces of nature whose spirits are considered aspects of God. It is possible to pray to one spirit as distinct from another but not as distinct from God. Often the highest manifestation of spirit, God, is prayed to directly. God is particularly associated with the winds, the sky, and birds, but these are not worshiped. The Dinka

attribute any remarkable occurrence to the direct influence of God and will sometimes mark the occasion with an appropriate ritual. Aspects of God (the universal spirit) are distinguished, chief of which is Deng (rain). For the Nuer, the Dinka, and other Nilotes, human beings are as ants to God, whose actions are not to be questioned and who is regarded as the judge of all human behavior.

Cattle

play a significant role in Nilotic rituals. Cattle are sacrifice

d to God as expiatory substitutes for their owners. The function is consistent with the significance of cattle in all aspects of Nilotic life. Among the Nuer, for example, and with some variations among the Dinka, cattle are the foundation of family and community life, essential to subsistence, marriage payments, and personal pride. The cattle shed is a shrine and meeting place, the center of the household; a man of substance, head of a family, and a leading figure in the community is called a "bull". Every man and the spirits themselves have ox

names that denote their characteristic qualities. These beliefs and institutions give meaning to the symbolism of the rubbing of ashes on a sacrificial cow's back in order to transfer the burden of the owner's sins to the animal.

The universal god of the Shilluk is more remote than that of the Nuer and Dinka and is addressed through the founder of the Shilluk royal clan. Nyiking, considered both man and god, is not clearly distinguished from the supreme deity in ritual, although the Shilluk may make the distinction in discussing their beliefs. The king (reth) of the Shilluk is regarded as divine, an idea that has never been accepted by the Nuer and Dinka.

All of the Nilotes and other peoples as well pay attention to ancestral spirits, the nature of the cult varying considerably as to the kinds of ancestors who are thought to have power in the lives of their descendants. Sometimes it may be the founding ancestors of the group whose spirits are potent. In many cases it is the recently deceased ancestors who are active and must be placated.

Of the wide range of natural forces thought to be activated by spirits, perhaps the most common is rain. Although southern Sudan does not suffer as acutely as northern Sudan from lack of rain, there has sometimes been a shortage

, particularly during the 1970s and 1980s and in 1990; this lack has created hardship, famine, and death amidst the travail of civil war. For this reason, rituals connected with rain have become important in many ethnic groups, and ritual specialists concerned with rain or thought to incarnate the spirit of rain are important figures.

The distinction between the natural and the supernatural that has emerged in the Western world

is not relevant to the traditional religions. Spirits may have much greater power than human beings, but their powers are perceived not as altering the way the world commonly works but as explaining occurrences in nature or in the social world.

Some men and women are also thought to have extraordinary powers. How these powers are believed to be acquired and exercised varies from group to group. In general, however, some people are thought to have inherited the capacity to harm others and to have a disposition to do so. Typically they are accused of inflicting illnesses on specific individuals, frequently their neighbors or kin. In some groups, it is thought that men and women who have no inherent power to harm may nevertheless do damage to others by manipulating images of the victim or items closely associated with that person.

Occasionally an individual may be thought of as a sorcerer. When illness or some other affliction strikes in a form that is generally attributed to a sorcerer, there are ways (typically some form of divination) of confirming that witchcraft was used and identifying the sorcerer.

The notions of sorcery are not limited to the southern Sudanese, but are to be found in varying forms among peoples, including nomadic and other Arabs, who consider themselves Muslims. A specific belief widespread among Arabs and other Muslim peoples is the notion of the evil eye. Although a physiological peculiarity of the eye (walleye or cross-eye

) may be considered indicative of the evil eye, any persons expressing undue interest in the private concerns of another may be suspected of inflicting deliberate harm by a glance. Unlike most witchcraft, where the perpetrator is known by and often close to the victim, the evil eye is usually attributed to strangers. Children are thought to be the most vulnerable.

Ways exist to protect oneself against sorcery or the evil eye. Many magico-religious specialists—diviners and sorcerers—deal with these matters in Sudanese societies. The diviner is able to determine whether witchcraft or sorcery is responsible for the affliction and to discover the source. He also protects and cures by providing amulets and other protective devices for a fee or by helping a victim punish (in occult fashion) the sorcerer in order to be cured of the affliction. If it is thought that an evil spirit has possessed

a person, an exorcist

may be called in. In some groups these tasks may be accomplished by the same person; in others the degree of specialization may be greater. In northern Sudan among Muslim peoples, the faqih may spend more of his time as diviner, dispenser of amulets, healer, and exorcist than as Qur'anic teacher, imam of a mosque, or mystic.

Sudan

Sudan , officially the Republic of the Sudan , is a country in North Africa, sometimes considered part of the Middle East politically. It is bordered by Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the northeast, Eritrea and Ethiopia to the east, South Sudan to the south, the Central African Republic to the...

, with most of the country's population adhering to Islam

Islam

Islam . The most common are and . : Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from ~~. The second vowel ranges from ~~~...

, Animism

Animism

Animism refers to the belief that non-human entities are spiritual beings, or at least embody some kind of life-principle....

, or Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

. More than half Sudan's population was Muslim in the early 1990s. Most Muslims (ca 90 %), lived in the north, where they constituted ca 85% percent or more of the population. The World Christian Encyclopaedia provides an estimate of the Christian population in 2000 of 16.7%. Most Christian Sudanese and adherents of local religious systems lived in southern Sudan. Islam had made inroads into the south, but more through the need to know Arabic than a profound belief in the tenets of the Quran. The SPLM, which in 1991 controlled most of southern Sudan, opposed the imposition of the Sharia

Sharia

Sharia law, is the moral code and religious law of Islam. Sharia is derived from two primary sources of Islamic law: the precepts set forth in the Quran, and the example set by the Islamic prophet Muhammad in the Sunnah. Fiqh jurisprudence interprets and extends the application of sharia to...

(Islamic law). Christianity has grown from about 5% of the southerners to 50-70% today. with most of the rest still attached to the indigenous religions of their forebears.

Both Darfur

Darfur

Darfur is a region in western Sudan. An independent sultanate for several hundred years, it was incorporated into Sudan by Anglo-Egyptian forces in 1916. The region is divided into three federal states: West Darfur, South Darfur, and North Darfur...

and Northern Sudan are mostly Muslim, whereas the South is Animist and Christian.

Islam

Most Sudanese Muslims are adherents of the SunniSunni Islam

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam. Sunni Muslims are referred to in Arabic as ʾAhl ūs-Sunnah wa āl-Ǧamāʿah or ʾAhl ūs-Sunnah for short; in English, they are known as Sunni Muslims, Sunnis or Sunnites....

branch of Islam; recently a growing number of Shias have emerged in Khartoum and surrounding villages. Sunni Islam in Sudan is not marked by a uniform body of belief and practice, however. Some Muslims opposed aspects of Sunni orthodoxy, and rites having a non-Islamic origin were widespread, being accepted as if they were integral to Islam, or sometimes being recognized as separate. Moreover, Sunni Islam in Sudan (as in much of Africa) has been characterized by the formation of religious orders or brotherhoods, each of which made special demands on its adherents.

Five pillars

Five Pillars of Islam

The Pillars of Islam are basic concepts and duties for accepting the religion for the Muslims.The Shi'i and Sunni both agree on the essential details for the performance of these acts, but the Shi'a do not refer to them by the same name .-Pillars of Shia:According to Shia Islam, the...

. The first pillar, the shahadah or profession of faith is the affirmation "There is no god but God (Allah) and Muhammad

Muhammad

Muhammad |ligature]] at U+FDF4 ;Arabic pronunciation varies regionally; the first vowel ranges from ~~; the second and the last vowel: ~~~. There are dialects which have no stress. In Egypt, it is pronounced not in religious contexts...

is his prophet." It is the first step in becoming a Muslim and a significant part of prayer. The second obligation is prayer at five specified times of the day

Salat

Salah is the practice of formal prayer in Islam. Its importance for Muslims is indicated by its status as one of the Five Pillars of Sunni Islam, of the Ten Practices of the Religion of Twelver Islam and of the 7 pillars of Musta'lī Ismailis...

. The third enjoins almsgiving

Zakat

Zakāt , one of the Five Pillars of Islam, is the giving of a fixed portion of one's wealth to charity, generally to the poor and needy.-History:Zakat, a practice initiated by Muhammed himself, has played an important role throughout Islamic history...

. The fourth requires fasting during daylight hours

Sawm

Sawm is an Arabic word for fasting regulated by Islamic jurisprudence. In the terminology of Islamic law, Sawm means to abstain from eating, drinking , having sex and anything against Islamic law...

in the month of Ramadan

Ramadan

Ramadan is the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, which lasts 29 or 30 days. It is the Islamic month of fasting, in which participating Muslims refrain from eating, drinking, smoking and sex during daylight hours and is intended to teach Muslims about patience, spirituality, humility and...

. The fifth requires a pilgrimage

Hajj

The Hajj is the pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia. It is one of the largest pilgrimages in the world, and is the fifth pillar of Islam, a religious duty that must be carried out at least once in their lifetime by every able-bodied Muslim who can afford to do so...

to Mecca

Mecca

Mecca is a city in the Hijaz and the capital of Makkah province in Saudi Arabia. The city is located inland from Jeddah in a narrow valley at a height of above sea level...

for those able to perform it, to participate in the special rites that occur during the twelfth month of the lunar calendar

Lunar calendar

A lunar calendar is a calendar that is based on cycles of the lunar phase. A common purely lunar calendar is the Islamic calendar or Hijri calendar. A feature of the Islamic calendar is that a year is always 12 months, so the months are not linked with the seasons and drift each solar year by 11 to...

.

Most Sudanese Muslims are born to the faith and meet the first requirement. Conformity to the second requirement is more variable. Many males in the cities and larger towns manage to pray five times a day: at dawn, noon, midafternoon, sundown, and evening. The well-to-do perform little work during Ramadan, and many businesses close or operate on reduced schedules. In the early 1990s, its observance appeared to be widespread, especially in urban areas and among sedentary Sudanese Muslims.

Pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey or search of great moral or spiritual significance. Typically, it is a journey to a shrine or other location of importance to a person's beliefs and faith...

to Mecca is less costly and arduous for the Sudanese than it is for many Muslims. Nevertheless, it takes time (or money if travel is by air), and the ordinary Sudanese Muslim has generally found it difficult to accomplish, rarely undertaking it before middle age. Some have joined pilgrimage societies into which members pay a small amount monthly and choose one of their number when sufficient funds have accumulated to send someone on the pilgrimage. A returned pilgrim is entitled to use the honorific title hajj or hajjih for a woman.

Another ceremony commonly observed is the great feast Id al Adha

Eid ul-Adha

Eid al-Adha or "Festival of Sacrifice" or "Greater Eid" is an important religious holiday celebrated by Muslims worldwide to commemorate the willingness of Abraham to sacrifice his son Ishmael as an act of obedience to God, before God intervened to provide him with a sheep— to sacrifice...

(also known as Id al Kabir), representing the sacrifice made during the last days of the pilgrimage. The centerpiece of the day is the slaughter of a sheep, which is distributed to the poor, kin, neighbors, and friends, as well as the immediate family.

Islam imposes a standard of conduct encouraging generosity, fairness, and honesty towards other Muslims. Sudanese Arabs, especially those who are wealthy, are expected by their coreligionists to be generous.

Islam in Sudanese law

In accordance with Islamic law most Sudanese Muslims do not eat porkIslamic dietary laws

Islamic dietary laws provide direction on what is to be considered clean and unclean regarding diet and related issues.-Overview:Islamic jurisprudence specifies which foods are ' and which are '...

. Conformity to the prohibitions on gambling and alcohol is less widespread. Usury

Usury

Usury Originally, when the charging of interest was still banned by Christian churches, usury simply meant the charging of interest at any rate . In countries where the charging of interest became acceptable, the term came to be used for interest above the rate allowed by law...

is also forbidden by Islamic law, but Islamic banks

Islamic banking

Islamic banking is banking or banking activity that is consistent with the principles of Islamic law and its practical application through the development of Islamic economics. Sharia prohibits the fixed or floating payment or acceptance of specific interest or fees for loans of money...

have developed other ways of making money available to the public.

In Sudan (until 1983) modern criminal and civil, including commercial, law generally prevailed. In the north, however, the sharia, was expected to govern what is usually called family and personal law, i.e., matters such as marriage, divorce, and inheritance. In the towns and in some sedentary communities sharia was accepted, but in other sedentary communities and among nomads local custom was likely to prevail particularly with respect to inheritance.

In September 1983, Nimeiri

Gaafar Nimeiry

Gaafar Muhammad an-Nimeiry was the Nubian President of Sudan from 1969 to 1985...

imposed the sharia throughout the land, eliminating the civil and penal codes by which the country had been governed in the twentieth century. Traditional Islamic punishments were imposed for theft, adultery, homicide

Hudud

Hudud is the word often used in Islamic literature for the bounds of acceptable behaviour and the punishments for serious crimes...

, and other crimes. The zealousness with which these punishments were carried out contributed to the fall of Nimeiri. Nevertheless, no successor government has shown inclination to abandon the sharia.

Other influences

Islam is monotheistic and insists that there can be no intercessors between an individual and God. Nevertheless, Sudanese Islam includes a belief in spiritSpirit

The English word spirit has many differing meanings and connotations, most of them relating to a non-corporeal substance contrasted with the material body.The spirit of a living thing usually refers to or explains its consciousness.The notions of a person's "spirit" and "soul" often also overlap,...

s as sources of illness or other afflictions and in magical ways of dealing with them. The imam

Imam

An imam is an Islamic leadership position, often the worship leader of a mosque and the Muslim community. Similar to spiritual leaders, the imam is the one who leads Islamic worship services. More often, the community turns to the mosque imam if they have a religious question...

of a mosque is a prayer leader and preacher of sermons. He may also be a teacher and in smaller communities combines both functions. In the latter role, he is called a faqih

Faqih

A Faqīh is an expert in fiqh, or, Islamic jurisprudence.A faqih is an expert in Islamic Law, and, as such, the word Faqih can literally be generally translated as Jurist.- The definition of Fiqh and its relation to the Faqih:...

(pl., fuqaha), although a faqih need not be an imam. In addition to teaching in the local Qur'anic school (khalwa), the faqih is expected to write texts (from the Qur'an) or magical verses to be used as amulets and cures. His blessing may be asked at births, marriages, deaths, and other important occasions, and he may participate in wholly non-Islamic harvest rites in some remote places. All of these functions and capacities make the faqih the most important figure in popular Islam. But he is not a priest. His religious authority is based on his putative knowledge of the Qur'an, the sharia, and techniques for dealing with occult

Occult

The word occult comes from the Latin word occultus , referring to "knowledge of the hidden". In the medical sense it is used to refer to a structure or process that is hidden, e.g...

threats to health and well- being. The notion that the words of the Qur'an will protect against the actions of evil spirits

Demon

call - 1347 531 7769 for more infoIn Ancient Near Eastern religions as well as in the Abrahamic traditions, including ancient and medieval Christian demonology, a demon is considered an "unclean spirit" which may cause demonic possession, to be addressed with an act of exorcism...

or the evil eye

Evil eye

The evil eye is a look that is believed by many cultures to be able to cause injury or bad luck for the person at whom it is directed for reasons of envy or dislike...

is deeply embedded in popular Islam, and the amulets prepared by the faqih are intended to protect their wearers against these dangers.

In Sudan as in much of African Islam, the cult of the saint

Saint

A saint is a holy person. In various religions, saints are people who are believed to have exceptional holiness.In Christian usage, "saint" refers to any believer who is "in Christ", and in whom Christ dwells, whether in heaven or in earth...

is of considerable importance, although some Muslims would reject it. The development of the cult is closely related to the presence of the religious orders; many who came to be considered saints on their deaths were founders or leaders of religious orders who in their lifetimes were thought to have barakah

Barakah

In Islam, Barakah is the beneficent force from God that flows through the physical and spiritual spheres as prosperity, protection, and happiness. Baraka is the continuity of spiritual presence and revelation that begins with God and flows through that and those closest to God. Baraka can be found...

, a state of blessedness implying an indwelling spiritual power inherent in the religious office. Baraka intensifies after death as the deceased becomes a wali

Wali

Walī , is an Arabic word meaning "custodian", "protector", "sponsor", or authority as denoted by its definition "crown". "Wali" is someone who has "Walayah" over somebody else. For example, in Fiqh the father is wali of his children. In Islam, the phrase ولي الله walīyu 'llāh...

(literally friend of God, but in this context translated as saint). The tomb and other places associated with the saintly being become the loci of the person's baraka, and in some views he or she becomes the guardian spirit of the locality. The intercession of the wali is sought on a variety of occasions, particularly by those seeking cures or by barren women desiring children. A saint's annual holy day is the occasion of a local festival that may attract a large gathering.

Better-educated Muslims in Sudan may participate in prayer at a saint's tomb but argue that prayer is directed only to God. Many others, however, see the saint not merely as an intercessor with and an agent of God, but also as a nearly autonomous source of blessing and power, thereby approaching "popular" as opposed to orthodox Islam.

Movements and religious orders

Islam made its deepest and longest lasting impact in Sudan through the activity of the Islamic religious brotherhoods or orders. These orders emerged in the Middle East in the twelfth century in connection with the development of SufismSufism

Sufism or ' is defined by its adherents as the inner, mystical dimension of Islam. A practitioner of this tradition is generally known as a '...

, a reaction based in mysticism

Mysticism

Mysticism is the knowledge of, and especially the personal experience of, states of consciousness, i.e. levels of being, beyond normal human perception, including experience and even communion with a supreme being.-Classical origins:...

to the strongly legalistic orientation of mainstream Islam. These orders first came to Sudan in the sixteenth century and became significant in the eighteenth. Sufism seeks for its adherents a closer personal relationship with God through special spiritual disciplines. The exercises (or dhikr

Dhikr

Dhikr , plural ; ), is an Islamic devotional act, typically involving the repetition of the Names of God, supplications or formulas taken from hadith texts and verses of the Qur'an. Dhikr is usually done individually, but in some Sufi orders it is instituted as a ceremonial activity...

) include reciting prayers and passages of the Qur'an and repeating the names, or attributes, of God while performing physical movements according to the formula established by the founder of the particular order. Singing and dancing may be introduced. The outcome of an exercise, which lasts much longer than the usual daily prayer, is often a state of ecstatic abandon.

A mystical or devotional way (sing. tariqa; pl. turuq) is the basis for the formation of particular orders, each of which is also called a tariqa. The specialists in religious law

Religious law

In some religions, law can be thought of as the ordering principle of reality; knowledge as revealed by a God defining and governing all human affairs. Law, in the religious sense, also includes codes of ethics and morality which are upheld and required by the God...

and learning initially looked askance at Sufism and the Sufi orders, but the leaders of Sufi orders in Sudan have won acceptance by acknowledging the significance of the sharia and not claiming that Sufism replaces it.

The principal turuq vary considerably in their practice and internal organization. Some orders are tightly organized in hierarchical fashion; others have allowed their local branches considerable autonomy. There may be as many as a dozen turuq in Sudan. Some are restricted to that country; others are widespread in Africa

Africa

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

or the Middle East

Middle East

The Middle East is a region that encompasses Western Asia and Northern Africa. It is often used as a synonym for Near East, in opposition to Far East...

. Several turuq, for all practical purposes independent, are offshoots of older orders and were established by men who altered in major or minor ways the tariqa of the orders to which they had formerly been attached.

The oldest and most widespread of the turuq is the Qadiriyah founded by Abdul Qadir Jilani in Baghdad

Baghdad

Baghdad is the capital of Iraq, as well as the coterminous Baghdad Governorate. The population of Baghdad in 2011 is approximately 7,216,040...

in the twelfth century and introduced into Sudan in the sixteenth. The Qadiriyah's principal rival and the largest tariqa in the western part of the country was the Tijaniyah, a sect begun by Sidi Ahmed al-Tidjani

Sidi Ahmed al-Tidjani

Mawlana Ahmed ibn Mohammed Tijani al-Hassani al-Maghribi , in Arabic سيدي أحمد التجاني is the founder of the Tijaniyya Sūfī order...

at Tijani in Morocco

Morocco

Morocco , officially the Kingdom of Morocco , is a country located in North Africa. It has a population of more than 32 million and an area of 710,850 km², and also primarily administers the disputed region of the Western Sahara...

, which eventually penetrated Sudan in about 1810 via the western Sahel

Sahel

The Sahel is the ecoclimatic and biogeographic zone of transition between the Sahara desert in the North and the Sudanian Savannas in the south.It stretches across the North African continent between the Atlantic Ocean and the Red Sea....

(a narrow band of savanna bordering the southern Sahara, stretching across Africa). Many Tijani became influential in Darfur

Darfur

Darfur is a region in western Sudan. An independent sultanate for several hundred years, it was incorporated into Sudan by Anglo-Egyptian forces in 1916. The region is divided into three federal states: West Darfur, South Darfur, and North Darfur...

, and other adherents settled in northern Kurdufan

Kurdufan

Kurdufan , also spelled Kordofan, is a former province of central Sudan. In 1994 it was divided into three new federal states: North Kurdufan, South Kurdufan, and West Kurdufan...

. Later on, a class of Tijani merchants arose as markets grew in towns and trade expanded, making them less concerned with providing religious leadership. Of greater importance to Sudan was the tariqa established by the followers of Sayyid Ahmad ibn Idris

Ahmad Ibn Idris al-Fasi

Ahmad Ibn Idris al-Laraishi al-Yamlahi al-Alami al-Idrisi al-Hasani was a mystic and a theologian, active in Morocco, North Africa, and Yemen. He had opposed the Ulema and tried to preach a vigorous form of Islam that is close to ordinary people....

, known as Al Fasi

Ahmad Ibn Idris al-Fasi

Ahmad Ibn Idris al-Laraishi al-Yamlahi al-Alami al-Idrisi al-Hasani was a mystic and a theologian, active in Morocco, North Africa, and Yemen. He had opposed the Ulema and tried to preach a vigorous form of Islam that is close to ordinary people....

, who died in 1837. Although he lived in Arabia and never visited Sudan, his students spread into the Nile Valley establishing indigenous Sudanese orders which include the Majdhubiyah, the Idrisiyah, the Ismailiyah, and the Khatmiyyah.

Much different in organization from the other brotherhoods is the Khatmiyyah (or Mirghaniyah after the name of the order's founder). Established in the early nineteenth century by Muhammad Uthman al Mirghani, it became the best organized and most politically oriented and powerful of the turuq in eastern Sudan (see Turkiyah

Turkiyah

The History of Sudan under Muhammad Ali and his successors traces the period from Muhammad Ali Pasha's invasion of Sudan in 1820 until the fall of Khartoum in 1885 to Muhammad Ahmad, the self-proclaimed Mahdi...

). Mirghani had been a student of Sayyid Ahmad ibn Idris and had joined several important orders, calling his own order the seal of the paths (Khatim at Turuq—hence Khatmiyyah). The salient features of the Khatmiyyah are the extraordinary status of the Mirghani family, whose members alone may head the order; loyalty to the order, which guarantees paradise; and the centralized control of the order's branches.

Ansar (Sudan)

The Ansar , or followers of the Mahdi, is a Sufi religious movement in the Sudan whose followers are disciples of Muhammad Ahmad , the self-proclaimed Mahdi....

, or followers of the Mahdi, whose present-day leader was Sadiq al-Mahdi

Sadiq al-Mahdi

Sadiq al-Mahdi is a Sudanese political and religious figure...

, the great-grandson of Muhammad Ahmad

Muhammad Ahmad

Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah was a religious leader of the Samaniyya order in Sudan who, on June 29, 1881, proclaimed himself as the Mahdi or messianic redeemer of the Islamic faith...

, who drove the Egyptian administration from Sudan in 1885.

Most other orders were either smaller or less well organized than the Khatmiyyah. Moreover, unlike many other African Muslims, Sudanese Muslims did not all seem to feel the need to identify with one or another tariqa, even if the affiliation were nominal. Many Sudanese Muslims preferred more political movements that sought to change Islamic society and governance to conform to their own visions of the true nature of Islam.

Mahdi

In Islamic eschatology, the Mahdi is the prophesied redeemer of Islam who will stay on Earth for seven, nine or nineteen years- before the Day of Judgment and, alongside Jesus, will rid the world of wrongdoing, injustice and tyranny.In Shia Islam, the belief in the Mahdi is a "central religious...

("the awaited guide in the right path"), the messenger of God and representative of the Prophet Muhammad, an assertion that became an article of faith

Articles of Faith

Articles of faith are sets of beliefs usually found in creeds, sometimes numbered, and often beginning with "We believe...", which attempt to more or less define the fundamental theology of a given religion, and especially in the Christian Church....

among the Ansar. He was sent, he said, to prepare the way for the second coming

Second Coming

In Christian doctrine, the Second Coming of Christ, the Second Advent, or the Parousia, is the anticipated return of Jesus Christ from Heaven, where he sits at the Right Hand of God, to Earth. This prophecy is found in the canonical gospels and in most Christian and Islamic eschatologies...

of the Prophet Isa

Islamic view of Jesus

In Islam, Jesus is considered to be a Messenger of God and the Masih who was sent to guide the Children of Israel with a new scripture, the Injīl or Gospel. The belief in Jesus is required in Islam, and a requirement of being a Muslim. The Qur'an mentions Jesus twenty-five times, more often, by...

(Jesus) and the impending end of the world. In anticipation of Judgment Day, it was essential that the people return to a simple and rigorous, even puritanical Islam (see Mahdiyah). The idea of the coming of a Mahdi has roots in Sunni Islamic traditions. The issue for Sudanese and other Muslims was whether Muhammad Ahmad was in fact the Mahdi.

In the century since the Mahdist uprising, the neo-Mahdist movement and the Ansar, supporters of Mahdism from the west, have persisted as a political force in Sudan. Many groups, from the Baqqara

Baggara

The Baggāra Arabs are a set of communities inhabiting the portion of Africa's Sahel between Lake Chad and southern Kordofan, numbering over one million. They have a common language which is one of the regional colloquial Arabic languages...

cattle nomads to the largely sedentary tribes on the White Nile

White Nile

The White Nile is a river of Africa, one of the two main tributaries of the Nile from Egypt, the other being the Blue Nile. In the strict meaning, "White Nile" refers to the river formed at Lake No at the confluence of the Bahr al Jabal and Bahr el Ghazal rivers...

, supported this movement. The Ansar were hierarchically organized under the control of Muhammad Ahmad's successors, who have all been members of the Mahdi family (known as the ashraf

Ashraf

Ashraf refers to someone claiming descent from Muhammad by way of his daughter Fatimah. The word is the plural of sharīf "noble", from sharafa "to be highborn"...

). The ambitions and varying political perspectives of different members of the family have led to internal conflicts, and it appeared that Sadiq al-Mahdi, putative leader of the Ansar since the early 1970s, did not enjoy the unanimous support of all Mahdists. Mahdist family political goals and ambitions seemed to have taken precedence over the movement's original religious mission. The modern-day Ansar were thus loyal more to the political descendants of the Mahdi than to the religious message of Mahdism.

A movement that spread widely in Sudan in the 1960s, responding to the efforts to secularize Islamic society, was the Muslim Brotherhood

Muslim Brotherhood

The Society of the Muslim Brothers is the world's oldest and one of the largest Islamist parties, and is the largest political opposition organization in many Arab states. It was founded in 1928 in Egypt by the Islamic scholar and schoolteacher Hassan al-Banna and by the late 1940s had an...

(Al Ikhwan al Muslimin). Originally the Muslim Brotherhood, often known simply as the Brotherhood, was conceived as a religious revivalist movement that sought to return to the fundamentals of Islam in a way that would be compatible with the technological innovations introduced from the West. Disciplined, highly motivated, and well financed the Brotherhood became a powerful political force during the 1970s and 1980s, although it represented only a small minority of Sudanese. In the government that was formed in June 1989, following a bloodless coup d'état, the Brotherhood exerted influence through its political wing, the National Islamic Front

National Islamic Front

The National Islamic Front is the Islamist political organization founded and led by Dr. Hassan al-Turabi that has influenced the Sudanese government since 1979, and dominated it since 1989...

(NIF) party, which included several cabinet members among its adherents.

Christianity

Equatoria

Equatoria is a region in the south of present-day South Sudan along the upper reaches of the White Nile. Originally a province of Egypt, it also contained most of Northern part of present day Uganda including Albert Lake...

: the Madi, Moru

Moru

Moru is an ethnic group of South Sudan. Most of them live in Equatoria. They speak Moru, a Central Sudanic language. Many members of this ethnicity are Christians, most being members of the Episcopal Church of the Sudan . The Pioneer missionary in the area was Dr Kenneth Grant Fraser of the Church...

, Azande

Azande

The Azande are a tribe of north Central Africa. Their number is estimated by various sources at between 1 and 4 million....

, and Bari

Bari people

The Bari ethnic groups in South Sudan occupy the Savanna lands of the White Nile Valley. They speak a language which is also called Bari. The name "Bari of the Nile Valley" would be fitting because the river Nile runs through the heart of the Bari land...

. The major churches in the Sudan are the Roman Catholic, the Anglican (represented by the Episcopal Church of the Sudan

Episcopal Church of the Sudan

The Episcopal Church of the Sudan is an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion in Sudan and South Sudan. The province consists of twenty-four dioceses, each headed by a bishop. One of the diocesan bishops is elected to serve as Archbishop of the Sudan, and represent the province to the rest...

) and the Presbyterian. The Dinka people, the largest of the Nilotic tribes is largely Anglican, and the Nuer, the second largest, Presbyterian. The Coptic Orthodox Church's influence is also still present in Sudan. Southern Sudanese communities might include a few Christians, but the rituals and world view of this part of Sudan are dissimilar to those of Western Christianity

Western Christianity

Western Christianity is a term used to include the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church and groups historically derivative thereof, including the churches of the Anglican and Protestant traditions, which share common attributes that can be traced back to their medieval heritage...

. The few communities that had formed around Western missions had disappeared with the dissolution of the missions in 1964.

The indigenous Christian churches in Sudan, with external support, continue their mission, however, and have opened new churches and repaired those destroyed in the continuing civil conflict. Originally the Nilotic

Nilotic

Nilotic people or Nilotes, in its contemporary usage, refers to some ethnic groups mainly in South Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, and northern Tanzania, who speak Nilotic languages, a large sub-group of the Nilo-Saharan languages...

peoples were indifferent to Christianity, but in the latter half of the twentieth century many people in the educated elite embraced its tenets, at least superficially. English and Christianity have become symbols of resistance to the Muslim government in the north, which has vowed to destroy both. Unlike the early civil strife of the 1960s and 1970s, the insurgency in the 1980s and the 1990s has taken on a religious character.

Indigenous religions

Each indigenous religion is unique to a specific ethnic groupEthnic group

An ethnic group is a group of people whose members identify with each other, through a common heritage, often consisting of a common language, a common culture and/or an ideology that stresses common ancestry or endogamy...

or part of a group, although several groups may share elements of belief and ritual because of common ancestry or mutual influence. The group serves as the congregation, and an individual usually belongs to that faith by virtue of membership in the group. Believing and acting in a religious mode is part of daily life and is linked to the social, political, and economic actions and relationships of the group. The beliefs and practices of indigenous religions in Sudan are not systematized, in that the people do not generally attempt to put together in coherent fashion the doctrines they hold and the rituals they practice.

The concept of a high spirit or divinity, usually seen as a creator and sometimes as ultimately responsible for the actions of lesser spirits, is common to most Sudanese groups. Often the higher divinity is remote, and believers treat the other spirits as autonomous, orienting their rituals to these spirits rather than to the high god. Such spirits may be perceived as forces of nature or as manifestations of ancestors. Spirits may intervene in people's lives, either because individuals or groups have transgressed the norms of the society or because they have failed to pay adequate attention to the ritual that should be addressed to the spirits.

The Nilotes acknowledge an active supreme deity, who is therefore the object of ritual, but the beliefs and rituals differ from group to group. The Nuer, for example, have no word corresponding solely and exclusively to God. The word sometimes so translated refers not only to the universal governing spirit but also to ancestors and forces of nature whose spirits are considered aspects of God. It is possible to pray to one spirit as distinct from another but not as distinct from God. Often the highest manifestation of spirit, God, is prayed to directly. God is particularly associated with the winds, the sky, and birds, but these are not worshiped. The Dinka

Dinka

The Dinka is an ethnic group inhabiting the Bahr el Ghazal region of the Nile basin, Jonglei and parts of southern Kordufan and Upper Nile regions. They are mainly agro-pastoral people, relying on cattle herding at riverside camps in the dry season and growing millet and other varieties of grains ...

attribute any remarkable occurrence to the direct influence of God and will sometimes mark the occasion with an appropriate ritual. Aspects of God (the universal spirit) are distinguished, chief of which is Deng (rain). For the Nuer, the Dinka, and other Nilotes, human beings are as ants to God, whose actions are not to be questioned and who is regarded as the judge of all human behavior.

Cattle

Cattle

Cattle are the most common type of large domesticated ungulates. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae, are the most widespread species of the genus Bos, and are most commonly classified collectively as Bos primigenius...

play a significant role in Nilotic rituals. Cattle are sacrifice

Sacrifice

Sacrifice is the offering of food, objects or the lives of animals or people to God or the gods as an act of propitiation or worship.While sacrifice often implies ritual killing, the term offering can be used for bloodless sacrifices of cereal food or artifacts...

d to God as expiatory substitutes for their owners. The function is consistent with the significance of cattle in all aspects of Nilotic life. Among the Nuer, for example, and with some variations among the Dinka, cattle are the foundation of family and community life, essential to subsistence, marriage payments, and personal pride. The cattle shed is a shrine and meeting place, the center of the household; a man of substance, head of a family, and a leading figure in the community is called a "bull". Every man and the spirits themselves have ox

Ox

An ox , also known as a bullock in Australia, New Zealand and India, is a bovine trained as a draft animal. Oxen are commonly castrated adult male cattle; castration makes the animals more tractable...

names that denote their characteristic qualities. These beliefs and institutions give meaning to the symbolism of the rubbing of ashes on a sacrificial cow's back in order to transfer the burden of the owner's sins to the animal.

The universal god of the Shilluk is more remote than that of the Nuer and Dinka and is addressed through the founder of the Shilluk royal clan. Nyiking, considered both man and god, is not clearly distinguished from the supreme deity in ritual, although the Shilluk may make the distinction in discussing their beliefs. The king (reth) of the Shilluk is regarded as divine, an idea that has never been accepted by the Nuer and Dinka.

All of the Nilotes and other peoples as well pay attention to ancestral spirits, the nature of the cult varying considerably as to the kinds of ancestors who are thought to have power in the lives of their descendants. Sometimes it may be the founding ancestors of the group whose spirits are potent. In many cases it is the recently deceased ancestors who are active and must be placated.

Of the wide range of natural forces thought to be activated by spirits, perhaps the most common is rain. Although southern Sudan does not suffer as acutely as northern Sudan from lack of rain, there has sometimes been a shortage

Drought

A drought is an extended period of months or years when a region notes a deficiency in its water supply. Generally, this occurs when a region receives consistently below average precipitation. It can have a substantial impact on the ecosystem and agriculture of the affected region...

, particularly during the 1970s and 1980s and in 1990; this lack has created hardship, famine, and death amidst the travail of civil war. For this reason, rituals connected with rain have become important in many ethnic groups, and ritual specialists concerned with rain or thought to incarnate the spirit of rain are important figures.

The distinction between the natural and the supernatural that has emerged in the Western world

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West and the Occident , is a term referring to the countries of Western Europe , the countries of the Americas, as well all countries of Northern and Central Europe, Australia and New Zealand...

is not relevant to the traditional religions. Spirits may have much greater power than human beings, but their powers are perceived not as altering the way the world commonly works but as explaining occurrences in nature or in the social world.

Some men and women are also thought to have extraordinary powers. How these powers are believed to be acquired and exercised varies from group to group. In general, however, some people are thought to have inherited the capacity to harm others and to have a disposition to do so. Typically they are accused of inflicting illnesses on specific individuals, frequently their neighbors or kin. In some groups, it is thought that men and women who have no inherent power to harm may nevertheless do damage to others by manipulating images of the victim or items closely associated with that person.

Occasionally an individual may be thought of as a sorcerer. When illness or some other affliction strikes in a form that is generally attributed to a sorcerer, there are ways (typically some form of divination) of confirming that witchcraft was used and identifying the sorcerer.

The notions of sorcery are not limited to the southern Sudanese, but are to be found in varying forms among peoples, including nomadic and other Arabs, who consider themselves Muslims. A specific belief widespread among Arabs and other Muslim peoples is the notion of the evil eye. Although a physiological peculiarity of the eye (walleye or cross-eye

Strabismus

Strabismus is a condition in which the eyes are not properly aligned with each other. It typically involves a lack of coordination between the extraocular muscles, which prevents bringing the gaze of each eye to the same point in space and preventing proper binocular vision, which may adversely...

) may be considered indicative of the evil eye, any persons expressing undue interest in the private concerns of another may be suspected of inflicting deliberate harm by a glance. Unlike most witchcraft, where the perpetrator is known by and often close to the victim, the evil eye is usually attributed to strangers. Children are thought to be the most vulnerable.

Ways exist to protect oneself against sorcery or the evil eye. Many magico-religious specialists—diviners and sorcerers—deal with these matters in Sudanese societies. The diviner is able to determine whether witchcraft or sorcery is responsible for the affliction and to discover the source. He also protects and cures by providing amulets and other protective devices for a fee or by helping a victim punish (in occult fashion) the sorcerer in order to be cured of the affliction. If it is thought that an evil spirit has possessed

Spiritual possession

Spirit possession is a paranormal or supernatural event in which it is said that spirits, gods, demons, animas, extraterrestrials, or other disincarnate or extraterrestrial entities take control of a human body, resulting in noticeable changes in health and behaviour...

a person, an exorcist

Exorcist

In some religions an exorcist is a person who is believed to be able to cast out the devil or other demons. A priest, a nun, a monk, a healer, a shaman or other specially prepared or instructed person can be an exorcist...

may be called in. In some groups these tasks may be accomplished by the same person; in others the degree of specialization may be greater. In northern Sudan among Muslim peoples, the faqih may spend more of his time as diviner, dispenser of amulets, healer, and exorcist than as Qur'anic teacher, imam of a mosque, or mystic.