Retreat from Gettysburg

Encyclopedia

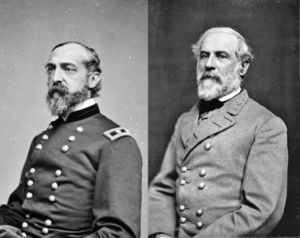

The Confederate

Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army was the army of the Confederate States of America while the Confederacy existed during the American Civil War. On February 8, 1861, delegates from the seven Deep South states which had already declared their secession from the United States of America adopted the...

Army of Northern Virginia

Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War, as well as the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed against the Union Army of the Potomac...

began its Retreat from Gettysburg on July 4, 1863. Following General Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War....

's failure to defeat the Union Army

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

at the Battle of Gettysburg

Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg , was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The battle with the largest number of casualties in the American Civil War, it is often described as the war's turning point. Union Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade's Army of the Potomac...

(July 1–3, 1863), he ordered a retreat through Maryland

Maryland

Maryland is a U.S. state located in the Mid Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware to its east...

and over the Potomac River

Potomac River

The Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay, located along the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States. The river is approximately long, with a drainage area of about 14,700 square miles...

to relative safety in Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

. The Union Army of the Potomac

Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the major Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War.-History:The Army of the Potomac was created in 1861, but was then only the size of a corps . Its nucleus was called the Army of Northeastern Virginia, under Brig. Gen...

, commanded by Maj. Gen.

Major general (United States)

In the United States Army, United States Marine Corps, and United States Air Force, major general is a two-star general-officer rank, with the pay grade of O-8. Major general ranks above brigadier general and below lieutenant general...

George G. Meade, was unable to maneuver quickly enough to launch a significant attack on the Confederates, who crossed the river on the night of July 13–14.

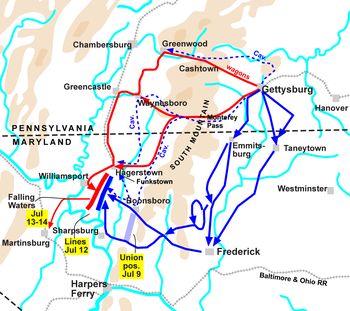

Confederate supplies and thousands of wounded men proceeded over South Mountain

South Mountain (Maryland and Pennsylvania)

South Mountain is the northern extension of the Blue Ridge Mountain range in Maryland and Pennsylvania. From the Potomac River near Knoxville, Maryland in the south, to Dillsburg, Pennsylvania in the north, the long range separates the Hagerstown and Cumberland valleys from the Piedmont regions of...

through Cashtown

Cashtown-McKnightstown, Pennsylvania

The Cashtown-McKnightstown Census Designated Place was the 2000 United States Census area designated by obsolete Census Code 11588 which has been replaced by the Cashtown and McKnightstown Census Designated Places, which the USGS designated as separate named places on August 30,...

in a wagon train that extended for 15–20 miles, enduring harsh weather, treacherous roads, and enemy cavalry raids. The bulk of Lee's infantry departed through Fairfield

Fairfield, Pennsylvania

Fairfield is a borough in Adams County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 486 at the 2000 census.-History:During the Gettysburg Campaign in the American Civil War, the Battle of Fairfield played an important role in securing the Fairfield pass and the Hagerstown Road, enabling Robert E...

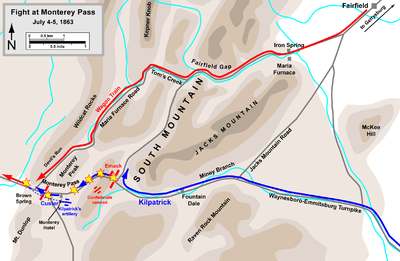

and through the Monterey Pass

Monterey pass

Monterey Pass is a mountain pass near Blue Ridge Summit, Pennsylvania, and the Mason-Dixon Line. The saddle area lies near between Monterey Peak and . It was the site of the July 1863 Fight at Monterey Pass during the Retreat from Gettysburg.-Gettysburg Campaign:The first military engagement at...

toward Hagerstown, Maryland

Hagerstown, Maryland

Hagerstown is a city in northwestern Maryland, United States. It is the county seat of Washington County, and, by many definitions, the largest city in a region known as Western Maryland. The population of Hagerstown city proper at the 2010 census was 39,662, and the population of the...

. Reaching the Potomac, they found that rising waters and destroyed pontoon bridges prevented their immediate crossing. Erecting substantial defensive works, they awaited the arrival of the Union army, which had been pursuing over longer roads more to the south of Lee's route. Before Meade could perform adequate reconnaissance and attack the Confederate fortifications, Lee's army escaped across fords and a hastily rebuilt bridge.

Combat operations, primarily cavalry battles, raids, and skirmishes, occurred during the retreat at Fairfield

Battle of Fairfield

The Battle of Fairfield was a cavalry engagement during the Gettysburg Campaign of the American Civil War. It was fought July 3, 1863, near Fairfield, Pennsylvania, concurrently with the Battle of Gettysburg, although it was not a formal part of that battle...

(July 3), Monterey Pass (July 4–5), Smithsburg

Smithsburg, Maryland

Smithsburg is a town in Washington County, Maryland, United States. Its population was 2,146 at the 2000 census and latest 2008 estimates are at 2,908. Smithsburg is close to Fort Ritchie army base and just west of the presidential retreat Camp David....

(July 5), Hagerstown

Hagerstown, Maryland

Hagerstown is a city in northwestern Maryland, United States. It is the county seat of Washington County, and, by many definitions, the largest city in a region known as Western Maryland. The population of Hagerstown city proper at the 2010 census was 39,662, and the population of the...

(July 6 and 12), Boonsboro

Battle of Boonsboro

The Battle of Boonsboro took place on July 8, 1863, in Washington County, Maryland, as part of the Retreat from Gettysburg during the Gettysburg Campaign of the American Civil War....

(July 8), Funkstown

Battle of Funkstown

The Second Battle of Funkstown took place near Funkstown, Maryland, on July 10, 1863, during the Gettysburg Campaign of the American Civil War...

(July 7 and 10), and around Williamsport

Battle of Williamsport

The Battle of Williamsport, also known as the Battle of Hagerstown or Falling Waters, took place from July 6 to July 16, 1863, in Washington County, Maryland, as part of the Gettysburg Campaign of the American Civil War....

and Falling Waters

Falling Waters, West Virginia

Falling Waters is an unincorporated census-designated place on the Potomac River in Berkeley County, West Virginia. It is located along Williamsport Pike north of Martinsburg. According to the 2010 census, Falling Waters has a population of 876....

(July 6–14). Additional clashes after the armies crossed the Potomac occurred at Shepherdstown

Shepherdstown, West Virginia

Shepherdstown is a town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States, located along the Potomac River. It is the oldest town in the state, having been chartered in 1762 by Colonial Virginia's General Assembly. Since 1863, Shepherdstown has been in West Virginia, and is the oldest town in...

(July 16) and Manassas Gap

Battle of Manassas Gap

The Battle of Manassas Gap, also known as the Battle of Wapping Heights, took place on July 23, 1863, in Warren County, Virginia, at the conclusion of General Robert E. Lee's retreat back to Virginia in the final days of the Gettysburg Campaign of the American Civil War...

(July 23) in Virginia, ending the Gettysburg Campaign

Gettysburg Campaign

The Gettysburg Campaign was a series of battles fought in June and July 1863, during the American Civil War. After his victory in the Battle of Chancellorsville, Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia moved north for offensive operations in Maryland and Pennsylvania. The...

of June and July 1863.

Background

The culmination of the three-day Battle of Gettysburg was the massive infantry assault known as Pickett's ChargePickett's Charge

Pickett's Charge was an infantry assault ordered by Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee against Maj. Gen. George G. Meade's Union positions on Cemetery Ridge on July 3, 1863, the last day of the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War. Its futility was predicted by the charge's commander,...

, in which the Confederate attack against the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge

Cemetery Ridge

Cemetery Ridge is a geographic feature in Gettysburg National Military Park south of the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, that figured prominently in the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1 to July 3, 1863. It formed a primary defensive position for the Union Army during the battle, roughly the center of...

was repulsed with significant losses. The Confederates returned to their positions on Seminary Ridge

Seminary Ridge

Seminary Ridge is a dendritic ridge which was an area of Battle of Gettysburg engagements during the American Civil War and of military installations during World War II.-Geography:...

and prepared to receive a counterattack. When the Union attack had not occurred by the evening of July 4, Lee realized that he could accomplish nothing more in his Gettysburg Campaign

Gettysburg Campaign

The Gettysburg Campaign was a series of battles fought in June and July 1863, during the American Civil War. After his victory in the Battle of Chancellorsville, Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia moved north for offensive operations in Maryland and Pennsylvania. The...

and that he had to return his battered army to Virginia. His ability to supply his army by living off the Pennsylvania countryside was now significantly reduced and the Union could easily bring up additional reinforcements as time passed, whereas he could not. Brig. Gen. William N. Pendleton

William N. Pendleton

William Nelson Pendleton was an American teacher, Episcopal priest, and soldier. He served as a Confederate general during the American Civil War, noted for his position as Gen. Robert E. Lee's chief of artillery for most of the conflict...

, Lee's artillery chief, reported to him that all of his long-range artillery ammunition had been expended and there were no early prospects for resupply. However, despite casualties of over 20,000 officers and men, including a number of senior officers, the morale of Lee's army remained high and their respect for the commanding general was not diminished by their reverses.

Lee began his preparations for retreat on the night of July 3, following a council of war

Council of war

A council of war is a term in military science that describes a meeting held to decide on a course of action, usually in the midst of a battle. Under normal circumstances, decisions are made by a commanding officer, optionally communicated and coordinated by staff officers, and then implemented by...

with some of his subordinate commanders. He consolidated his lines by pulling Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell

Richard S. Ewell

Richard Stoddert Ewell was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate general during the American Civil War. He achieved fame as a senior commander under Stonewall Jackson and Robert E...

's Second Corps

Second Corps, Army of Northern Virginia

The Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia was a military organization within the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia during much of the American Civil War. It was officially created and named following the Battle of Sharpsburg in 1862, but comprised units in a corps organization for quite...

from the Culp's Hill

Culp's Hill

Culps Hill is a Battle of Gettysburg landform south of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, with a heavily wooded summit of . The east slope is to Rock Creek , 160 feet lower in elevation, and the west slope is to a saddle with Stevens Knoll with a summit lower than the Culps Hill summit...

area back through the town of Gettysburg and onto Oak Ridge and Seminary Ridge. His men constructed breastworks and rifle pits that extended 2.5 miles from the Mummasburg Road to the Emmitsburg Road. He decided to send his long train of wagons carrying equipment and supplies, which had been captured in great quantities throughout the campaign, to the rear as quickly as possible, in advance of the infantry. The wagon train included ambulances with his 8,000 wounded men who were fit to travel, as well as some of the key general officers who were severely wounded, but too important to be abandoned. The great bulk of the Confederate wounded—over 6,800 men—remained behind to be treated in Union field hospitals and by a few of Lee's surgeons selected to stay with them.

There were two routes the army could take over South Mountain

South Mountain (Maryland and Pennsylvania)

South Mountain is the northern extension of the Blue Ridge Mountain range in Maryland and Pennsylvania. From the Potomac River near Knoxville, Maryland in the south, to Dillsburg, Pennsylvania in the north, the long range separates the Hagerstown and Cumberland valleys from the Piedmont regions of...

to the Cumberland Valley

Cumberland Valley

The Cumberland Valley is a constituent valley of the Great Appalachian Valley and a North American agricultural region within the Atlantic Seaboard watershed in Pennsylvania and Maryland....

(the name given to the Shenandoah Valley

Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley is both a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians , to the north by the Potomac River...

in Maryland and Pennsylvania), from where it would march south to cross the Potomac at Williamsport, Maryland

Williamsport, Maryland

Williamsport is a town in Washington County, Maryland, United States. The population was 1,868 at the 2000 census and 2,278 as of July 2008.-Geography: Williamsport is located at ....

: the Chambersburg Pike, which passed through Cashtown

Cashtown-McKnightstown, Pennsylvania

The Cashtown-McKnightstown Census Designated Place was the 2000 United States Census area designated by obsolete Census Code 11588 which has been replaced by the Cashtown and McKnightstown Census Designated Places, which the USGS designated as separate named places on August 30,...

in the direction of Chambersburg

Chambersburg, Pennsylvania

Chambersburg is a borough in the South Central region of Pennsylvania, United States. It is miles north of Maryland and the Mason-Dixon line and southwest of Harrisburg in the Cumberland Valley, which is part of the Great Appalachian Valley. Chambersburg is the county seat of Franklin County...

, and; the shorter route through Fairfield

Fairfield, Pennsylvania

Fairfield is a borough in Adams County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 486 at the 2000 census.-History:During the Gettysburg Campaign in the American Civil War, the Battle of Fairfield played an important role in securing the Fairfield pass and the Hagerstown Road, enabling Robert E...

and over Monterey Pass

Monterey pass

Monterey Pass is a mountain pass near Blue Ridge Summit, Pennsylvania, and the Mason-Dixon Line. The saddle area lies near between Monterey Peak and . It was the site of the July 1863 Fight at Monterey Pass during the Retreat from Gettysburg.-Gettysburg Campaign:The first military engagement at...

to Hagerstown

Hagerstown, Maryland

Hagerstown is a city in northwestern Maryland, United States. It is the county seat of Washington County, and, by many definitions, the largest city in a region known as Western Maryland. The population of Hagerstown city proper at the 2010 census was 39,662, and the population of the...

. Fortunately for the Confederate army, it now had its full complement of cavalry available for reconnaissance and screening activities, a capability it lacked earlier in the campaign while its commander, Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart

J.E.B. Stuart

James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart was a U.S. Army officer from Virginia and a Confederate States Army general during the American Civil War. He was known to his friends as "Jeb", from the initials of his given names. Stuart was a cavalry commander known for his mastery of reconnaissance and the use...

, was separated from the army with his three best cavalry brigades on "Stuart's ride".

Unfortunately for the Confederate Army, however, once they reached the Potomac they would find it difficult to cross. Torrential rains that started on July 4 flooded the river at Williamsport, making fording impossible. Four miles downstream at Falling Waters

Falling Waters, West Virginia

Falling Waters is an unincorporated census-designated place on the Potomac River in Berkeley County, West Virginia. It is located along Williamsport Pike north of Martinsburg. According to the 2010 census, Falling Waters has a population of 876....

, Union cavalry dispatched from Harpers Ferry by Maj. Gen. William H. French

William H. French

William Henry French was a career United States Army officer and a Union Army General in the American Civil War. He rose to temporarily command a corps within the Army of the Potomac, but was relieved of active field duty following poor performance during the Mine Run Campaign in late 1863.-Early...

destroyed Lee's lightly guarded pontoon bridge on July 4. The only way to cross the river was a small ferry at Williamsport. The Confederates could potentially be trapped, forced to defend themselves against Meade with their backs to the river.

Opposing forces

The Union Army of the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia retained their general organizations with which they fought at the Battle of Gettysburg. By July 10, some of the Union battle losses had been replaced and Meade's Army stood at about 80,000 men. The Confederates received no reinforcements during the campaign and had only about 50,000 men available.The Army of the Potomac had significant changes in general officer assignments because of its battle losses. Meade's chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Daniel Butterfield

Daniel Butterfield

Daniel Adams Butterfield was a New York businessman, a Union General in the American Civil War, and Assistant U.S. Treasurer in New York. He is credited with composing the bugle call Taps and was involved in the Black Friday gold scandal in the Grant administration...

, was wounded on July 3 and was replaced on July 8 by Maj. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys

Andrew A. Humphreys

Andrew Atkinson Humphreys , was a career United States Army officer, civil engineer, and a Union General in the American Civil War. He served in senior positions in the Army of the Potomac, including division command, chief of staff, and corps command, and was Chief Engineer of the U.S...

; Brig. Gen. Henry Price replaced Humphreys in command of his old division of the III Corps. Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds

John F. Reynolds

John Fulton Reynolds was a career United States Army officer and a general in the American Civil War. One of the Union Army's most respected senior commanders, he played a key role in committing the Army of the Potomac to the Battle of Gettysburg and was killed at the start of the battle.-Early...

, killed on July 1, was replaced by Maj. Gen. John Newton of the VI Corps. Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock of the II Corps, wounded on July 3, was replaced by Brig. Gen. William Hays

William Hays (general)

William Hays was a career officer in the United States Army, serving as a Union Army general during the American Civil War.-Early life:...

. Maj. Gen. William H. French

William H. French

William Henry French was a career United States Army officer and a Union Army General in the American Civil War. He rose to temporarily command a corps within the Army of the Potomac, but was relieved of active field duty following poor performance during the Mine Run Campaign in late 1863.-Early...

, who had temporarily commanded the garrison at Harpers Ferry for most of the campaign, replaced the wounded Daniel E. Sickles in command of the III Corps on July 7. In addition to the battle losses, Meade's army was plagued by a condition that persisted during the war, the departure of men and regiments whose enlistments had expired, which took effect even in the midst of an active campaign. On the plus side, however, Meade had available temporary, although inexperienced, reinforcements of about 10,000 men who had been with General French at Maryland Heights, which were incorporated into the I Corps and III Corps. The net effect of expiring enlistments and reinforcements added about 6,000 men to the Army of the Potomac. Including the forces around Harpers Ferry, Maryland Heights, and the South Mountain passes, by July 14 between 11,000 and 12,000 men had been added the army, although Meade had extreme doubts about the combat effectiveness of these troops. In addition to the Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. Darius N. Couch

Darius N. Couch

Darius Nash Couch was an American soldier, businessman, and naturalist. He served as a career U.S. Army officer during the Mexican-American War, the Second Seminole War, and as a general officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War.During the Civil War, Couch fought notably in the...

of the Department of the Susquehanna

Department of the Susquehanna

The Department of the Susquehanna was a military department created by the United States War Department during the Gettysburg Campaign of the American Civil War...

had 7,600 men at Waynesboro, 11,000 at Chambersburg, and 6,700 at Mercersburg. These were "emergency troops" that were hastily raised during Lee's march into Pennsylvania and were subject to Meade's orders.

Lee's army retained its corps organization and commanders, although a number of key subordinate generals were killed (Lewis A. Armistead, Richard B. Garnett

Richard B. Garnett

Richard Brooke Garnett was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate general in the American Civil War. He was killed during Pickett's Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg.-Early life:...

, Isaac E. Avery

Isaac E. Avery

Isaac Erwin Avery was a planter and an officer in the Confederate States Army. He died at the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War...

), captured (James L. Kemper

James L. Kemper

James Lawson Kemper was a lawyer, a Confederate general in the American Civil War, and the 37th Governor of Virginia...

and James J. Archer

James J. Archer

James Jay Archer was a lawyer and an officer in the United States Army during the Mexican-American War, and he later served as a general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War....

), or severely wounded (John B. Hood, Wade Hampton

Wade Hampton III

Wade Hampton III was a Confederate cavalry leader during the American Civil War and afterward a politician from South Carolina, serving as its 77th Governor and as a U.S...

, George T. Anderson

George T. Anderson

George Thomas Anderson was a general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. Nicknamed "Tige," Anderson was noted as one of Robert E...

, Dorsey Pender

William Dorsey Pender

William Dorsey Pender was one of the youngest, and most promising, generals fighting for the Confederacy in the American Civil War. He was mortally wounded at the Battle of Gettysburg.-Early life:...

, and Alfred M. Scales).

Imboden's wagon train

John D. Imboden

John Daniel Imboden was a lawyer, teacher, Virginia state legislator. During the American Civil War, he was a Confederate cavalry general and partisan fighter...

, one of Stuart's cavalry brigade commanders, to manage the passage of the majority of the trains to the rear. Imboden's command of 2,100 cavalrymen had not played much of a role in the campaign up until this time, and had not been selected by Stuart for his ride around the Union Army. Lee and Stuart had a poor opinion of Imboden's brigade, considering it "indifferently disciplined and inefficiently directed," but it was effective for assignments such as guard duty or fighting militia. Lee reinforced Imboden's single artillery battery with five additional batteries borrowed from his infantry corps and directed Stuart to assign the brigades of Brig. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee

Fitzhugh Lee

Fitzhugh Lee , nephew of Robert E. Lee, was a Confederate cavalry general in the American Civil War, the 40th Governor of Virginia, diplomat, and United States Army general in the Spanish-American War.-Early life:...

and Wade Hampton (now commanded by Col. Laurence S. Baker

Laurence S. Baker

Laurence Simmons Baker was an officer in the United States Army on the frontier, then later a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War...

) to protect the flanks and rear of Imboden's column. Imboden's orders were to depart Cashtown on the evening of July 4, turn south at Greenwood

Fayetteville, Pennsylvania

Fayetteville is a census-designated place in Franklin County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 2,774 at the 2000 census.-Geography:Fayetteville is located at ....

, avoiding Chambersburg, take the direct road to Williamsport to ford across the Potomac, and escort the train as far as Martinsburg

Martinsburg, West Virginia

Martinsburg is a city in the Eastern Panhandle region of West Virginia, United States. The city's population was 14,972 at the 2000 census; according to a 2009 Census Bureau estimate, Martinsburg's population was 17,117, making it the largest city in the Eastern Panhandle and the eighth largest...

. Then, Imboden's command would return to Hagerstown to guard the retreat route for the remainder of the army.

Imboden's train consisted of hundreds of Conestoga-style wagons

Conestoga wagon

The Conestoga wagon is a heavy, broad-wheeled covered wagon that was used extensively during the late 18th century and the 19th century in the United States and sometimes in Canada as well. It was large enough to transport loads up to 8 tons , and was drawn by horses, mules or oxen...

, which extended 15-20 miles along the narrow roads. Assembling these wagons into a marching column, arranging their escorts, loading supplies, and accounting for the wounded took until late afternoon on July 5. Imboden himself left Cashtown around 8 p.m. to join the head of his column. The journey was one of extreme misery, conducted during the torrential rains that began on July 4, in which the wounded men were forced to endure the weather and the rough roads in wagons without suspensions. Imboden's orders required that he not stop until he reached his destination, which meant that wagons breaking down were left behind. Some critically wounded men were left behind on the roadsides as well, hoping that local civilians would find and take care of them. The train was harassed throughout its march. At dawn on July 5, civilians in Greencastle

Greencastle, Pennsylvania

Greencastle is a borough in Franklin County in south-central Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 3,722 at the 2000 census.-History:...

ambushed the train with axes, attacking the wheels of the wagons, until they were driven off. That afternoon at Cunningham's Cross Roads (current day Cearfoss, Maryland

Cearfoss, Maryland

Cearfoss is an unincorporated community in northwestern Washington County, Maryland, United States. It is located northwest of Hagerstown and Maugansville near the Pennsylvania border. Many highways intersect in Cearfoss in a roundabout including Maryland Route 63, Maryland Route 58, and Maryland...

), Capt. Abram Jones led 200 troopers of the 1st New York Cavalry and 12th Pennsylvania Cavalry in attacking the column, capturing 134 wagons, 600 horses and mules, and 645 prisoners, about half of whom were wounded. These losses so angered Stuart that he demanded a court of inquiry to investigate.

Fairfield and Monterey Pass

James Longstreet

James Longstreet was one of the foremost Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Horse." He served under Lee as a corps commander for many of the famous battles fought by the Army of Northern Virginia in the...

's First Corps

First Corps, Army of Northern Virginia

The First Corps, Army of Northern Virginia was a military unit fighting for the Confederate States of America in the American Civil War. It was formed in early 1861 and served until the spring of 1865, mostly in the Eastern Theater. The corps was commanded by James Longstreet for much of its...

and Richard S. Ewell

Richard S. Ewell

Richard Stoddert Ewell was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate general during the American Civil War. He achieved fame as a senior commander under Stonewall Jackson and Robert E...

's Second Corps

Second Corps, Army of Northern Virginia

The Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia was a military organization within the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia during much of the American Civil War. It was officially created and named following the Battle of Sharpsburg in 1862, but comprised units in a corps organization for quite...

. Lee accompanied Hill at the head of the column. He ordered Stuart to post Col. John R. Chambliss

John R. Chambliss

John Randolph Chambliss, Jr. was a career military officer, serving in the United States Army and then, during the American Civil War, in the Confederate States Army. A brigadier general of cavalry, Chambliss was killed in action during the Second Battle of Deep Bottom.-Early life:Chambliss was...

's and Brig. Gen. Albert G. Jenkins

Albert G. Jenkins

Albert Gallatin Jenkins was an attorney, planter, representative to the United States Congress and First Confederate Congress, and a Confederate brigadier general during the American Civil War...

's brigades (the latter commanded by Col. Milton Ferguson) to cover his left rear from Emmitsburg. Departing in the dark, Lee had the advantage of getting several hours head start and the route from the west side of the battlefield to Williamsport was about half as long as the ones available to the Army of the Potomac.

Meade was reluctant to begin an immediate pursuit because he was unsure whether Lee intended to attack again and his orders continued that he was required to protect the cities of Baltimore

Baltimore

Baltimore is the largest independent city in the United States and the largest city and cultural center of the US state of Maryland. The city is located in central Maryland along the tidal portion of the Patapsco River, an arm of the Chesapeake Bay. Baltimore is sometimes referred to as Baltimore...

and Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

Since Meade believed that the Confederates had well fortified the South Mountain passes, he decided he would pursue Lee on the east side of the mountains, conduct forced marches to quickly seize the passes west of Frederick, Maryland

Frederick, Maryland

Frederick is a city in north-central Maryland. It is the county seat of Frederick County, the largest county by area in the state of Maryland. Frederick is an outlying community of the Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is part of a greater...

, and threaten Lee's left flank as he retreated up the Cumberland Valley. However, Meade's assumption was wrong—Fairfield was lightly held by only two small cavalry brigades and the passes over South Mountain were not fortified. If Meade had secured Fairfield, Lee's army would have been forced to either fight its way through Fairfield while its rear was exposed to the Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg or to take his entire army through the Cashtown Pass, a much more difficult route to Hagerstown.

On July 3, while Pickett's Charge was underway, the Union cavalry had had a unique opportunity to impede Lee's eventual retreat. Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt

Wesley Merritt

Wesley Merritt was a general in the United States Army during the American Civil War and the Spanish-American War. He is noted for distinguished service in the cavalry.-Early life:...

's brigade departed from Emmitsburg

Emmitsburg, Maryland

-Demographics:As of the census of 2000, there were 2,290 people, 811 households, and 553 families residing in the town. The population density was 1,992.9 people per square mile . There were 862 housing units at an average density of 750.2 per square mile...

with orders from cavalry commander Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton

Alfred Pleasonton

Alfred Pleasonton was a United States Army officer and General of Union cavalry during the American Civil War. He commanded the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac during the Gettysburg Campaign, including the largest predominantly cavalry battle of the war, Brandy Station...

to strike the Confederate left and rear along Seminary Ridge. Reacting to a report from a local civilian that there was a Confederate forage train near Fairfield, Merritt dispatched about 400 men in four squadrons from the 6th U.S. Cavalry under Major Samuel H. Starr

Samuel H. Starr

Samuel Henry Starr was a career United States Army Officer, regimental commander and prisoner of war. A collection of his letters provide a rare view of military life, the War with Mexico, Indian conflicts, the Civil War, his fall from grace, recovery and post Civil War service...

to seize the wagons. Before they were able to reach the wagons, the 7th Virginia Cavalry, leading a column under Confederate Brig. Gen. William E. "Grumble" Jones

William E. Jones

William Edmondson Jones, known as Grumble Jones, was a planter, a career United States Army officer, and a Confederate cavalry general, killed in the Battle of Piedmont in the American Civil War.-Early life:...

, intercepted the regulars, starting the minor Battle of Fairfield

Battle of Fairfield

The Battle of Fairfield was a cavalry engagement during the Gettysburg Campaign of the American Civil War. It was fought July 3, 1863, near Fairfield, Pennsylvania, concurrently with the Battle of Gettysburg, although it was not a formal part of that battle...

. Taking cover behind a post-and rail fence, the U.S. cavalrymen opened fire and caused the Virginians to retreat. Jones sent in the 6th Virginia Cavalry, which successfully charged and swarmed over the Union troopers, wounding and capturing Starr. There were 242 Union casualties, primarily prisoners, and 44 casualties among the Confederates. Despite the relatively small scale of this action, its result was that the strategically important Fairfield Road to the South Mountain passes remained open.

Early on July 4 Meade send his cavalry to strike the enemy's rear and lines of communication so as to "harass and annoy him as much as possible in his retreat." Eight of nine cavalry brigades (except Col. John B. McIntosh's of Brig. Gen. David McM. Gregg's division) took to the field. Col. J. Irvin Gregg

John Irvin Gregg

John Irvin Gregg was a career U.S. Army officer. He fought in the Mexican-American War and during the American Civil War as a general officer in the Union army.-Early life and career:...

's brigade (of his cousin David Gregg's division) moved toward Cashtown via Hunterstown and the Mummasburg Road, but all of the others moved south of Gettysburg. Brig. Gen. John Buford

John Buford

John Buford, Jr. was a Union cavalry officer during the American Civil War, with a prominent role at the start of the Battle of Gettysburg.-Early years:...

's division went directly from Westminster

Westminster, Maryland

Westminster is a city in northern Maryland, United States. It is the seat of Carroll County. The city's population was 18,590 at the 2010 census. Westminster is an outlying community within the Baltimore-Towson, MD MSA, which is part of a greater Washington-Baltimore-Northern Virginia, DC-MD-VA-WV...

to Frederick, where they were joined by Merritt's division on the night of July 5.

Late on July 4, Meade held a council of war in which his corps commanders agreed that the army should remain at Gettysburg until Lee acted, and that the cavalry should pursue Lee in any retreat. Meade decided to have Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren

Gouverneur K. Warren

Gouverneur Kemble Warren was a civil engineer and prominent general in the Union Army during the American Civil War...

take a division from Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick

John Sedgwick

John Sedgwick was a teacher, a career military officer, and a Union Army general in the American Civil War. He was the highest ranking Union casualty in the Civil War, killed by a sniper at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House.-Early life:Sedgwick was born in the Litchfield Hills town of...

's VI Corps—the most lightly engaged of all the Union corps at Gettysburg—to probe the Confederate line and determine Lee's intentions. Meade ordered Butterfield to prepare for a general movement of the army, which he organized into three wings, commanded by Sedgwick (I, III, and VI Corps), Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum (II and XII), and Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard

Oliver O. Howard

Oliver Otis Howard was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War...

(V and XI). By the morning of July 5, Meade learned of Lee's departure, but he hesitated to order a general pursuit until he had received the results of Warren's reconnaissance.

The Battle of Monterey Pass began as Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick's cavalry division arrived near Fairfield on July 4 just before dark. They easily brushed aside Brig. Gen. Beverly Robertson

Beverly Robertson

Beverly Holcombe Robertson was a cavalry officer in the United States Army on the Western frontier and a Confederate general during the American Civil War.-Early life:...

's pickets and encountered a detachment of 20 men from the Confederate 1st Maryland Cavalry Battalion, under Capt. G. M. Emack, that was guarding the road to Monterey Pass. Aided by a detachment of the 4th North Carolina Cavalry and a single cannon, the Marylanders delayed the advance of 4,500 Union cavalrymen until well after midnight. Kilpatrick was not able to see anything in the dark and considered his command to be in "a perilous situation." He ordered Brig. Gen. George A. Custer to charge the Confederates with the 6th Michigan Cavalry, which broke the deadlock and allowed Kilpatrick's men to reach and attack the wagon train. They captured or destroyed numerous wagons and captured 1,360 prisoners—primarily wounded men in ambulances—and a large number of horses and mules.

Following the fight at Monterey, Kilpatrick's division reached Smithsburg

Smithsburg, Maryland

Smithsburg is a town in Washington County, Maryland, United States. Its population was 2,146 at the 2000 census and latest 2008 estimates are at 2,908. Smithsburg is close to Fort Ritchie army base and just west of the presidential retreat Camp David....

around 2 p.m. on July 5. Stuart arrived from over South Mountain with the brigades of Chambliss and Ferguson. A horse artillery

Horse artillery

Horse artillery was a type of light, fast-moving and fast-firing artillery which provided highly mobile fire support to European and American armies from the 17th to the early 20th century...

duel ensued, causing some damage to the small town. Kilpatrick withdrew at dark "to save my prisoners, animals, and wagons" and arrived at Boonsboro

Boonsboro, Maryland

Boonsboro is a town in Washington County, Maryland, United States, located at the foot of South Mountain. It nearly borders Frederick County and is proximate to the Antietam National Battlefield...

(spelled Boonsborough at that time) before midnight.

Sedgwick's reconnaissance

The reconnaissance from Sedgwick's corps began before dawn on the morning of July 5, but instead of a division they took the entire corps. It struck the rear guard of Ewell's corps late in the afternoon at Granite Hill near Fairfield, but the result was little more than a skirmish, and the Confederates camped a mile and a half west of Fairfield, holding their position with only their picket line. Warren informed Meade that he and Sedgwick believed Lee was concentrating the main body of his army around Fairfield and preparing for battle. Meade immediately halted his army and early on the morning of July 6, he ordered Sedgwick to resume his reconnaissance to determine Lee's intentions and the status of the mountain passes. Sedgwick argued with him about the risky nature of sending his entire corps into the rugged country and dense fog ahead of him and by noon Meade abandoned his plan, resuming his original intention of advancing east of the mountains to Middletown, MarylandMiddletown, Maryland

Middletown is a town in Frederick County, Maryland, United States. The population was 2,668 at the 2000 census. Middletown is a small, rural community steeped in American history...

. The delays leaving Gettysburg and the conflicting orders to Sedgwick about whether to conduct merely a reconnaissance or a vigorous advance to engage Lee's army in combat would later cause Meade political difficulties as his opponents charged him with indecision and timidity.

Given the conflicting signals from Meade, Sedgwick and Warren followed the more conservative course. They waited to start until Ewell's Corps had cleared out of Fairfield and remained at a safe distance behind it as it moved west. Lee assumed that Sedgwick would attack his rear and was ready for it. He told Ewell, "If these people keep coming on, turn back and thresh them." Ewell replied, "By the blessing of Providence I will do it" and ordered Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes

Robert E. Rodes

Robert Emmett Rodes was a railroad civil engineer and a promising young Confederate general in the American Civil War, killed in battle in the Shenandoah Valley.-Education, antebellum career:...

's division to form a battle line. The VI Corps followed Lee only to the top of Monterey Pass, however, and did not pursue down the other side.

Pursuit to Williamsport

Before Meade's infantry began to march in earnest in pursuit of Lee, Buford's cavalry division departed from Frederick to destroy Imboden's train before it could cross the Potomac. Hagerstown was a key point on the Confederate retreat route, and seizing it might block or delay their access to the fords across the river. On July 6, Kilpatrick's division, after its success raiding at Monterey Pass, moved toward Hagerstown and pushed out the two small brigades of Chambliss and Robertson. However, infantry commanded by Brig. Gen. Alfred IversonAlfred Iverson, Jr.

Alfred Iverson, Jr. was a lawyer, an officer in the Mexican-American War, a U.S. Army cavalry officer, and a Confederate general in the American Civil War. He served in the 1862–63 campaigns of the Army of Northern Virginia as a regimental and later brigade commander...

drove Kilpatrick's men back through the streets of town. Stuart's remaining brigades came up and were reinforced by two brigades of Hood's Division and Hagerstown was recaptured by the Confederates.

Buford heard Kilpatrick's artillery in the vicinity and requested support on his right. Kilpatrick chose to respond to Buford's request for assistance and join the attack on Imboden at Williamsport. Stuart's men pressured Kilpatrick's rear and right flank from their position at Hagerstown and Kilpatrick's men gave way and exposed Buford's rear to the attack. Buford gave up his effort when darkness fell. At 5 p.m. on July 7 Buford's men reached within a half-mile of the parked trains, but Imboden's command repulsed their advance.

Battle of Boonsboro

The Battle of Boonsboro took place on July 8, 1863, in Washington County, Maryland, as part of the Retreat from Gettysburg during the Gettysburg Campaign of the American Civil War....

occurred along the National Road

National Road

The National Road or Cumberland Road was the first major improved highway in the United States to be built by the federal government. Construction began heading west in 1811 at Cumberland, Maryland, on the Potomac River. It crossed the Allegheny Mountains and southwestern Pennsylvania, reaching...

on July 8. Stuart advanced from the direction of Funkstown and Williamsport with five brigades. He first encountered Union resistance at Beaver Creek Bridge, 4.5 miles north of Boonsboro. By 11 a.m., the Confederate cavalry had pushed forward to several mud-soaked fields, where fighting on horseback was nearly impossible, forcing Stuart's troopers and Kilpatrick's and Buford's divisions to fight dismounted. By mid-afternoon, the Union left under Kilpatrick crumbled as the Federals ran low on ammunition under increasing Confederate pressure. Stuart's advance ended about 7 p.m., however, when Union infantry arrived, and Stuart withdrew north to Funkstown

Funkstown, Maryland

Funkstown is a town in Washington County, Maryland, United States. The population was 983 at the 2000 census.-History:Originally were sold to Henry Funk by Frederick Calvert in 1754 and settled as Jerusalem.Funck’s Jerusalem Town...

.

Stuart's strong presence at Funkstown threatened any Union advance toward Williamsport, posing a serious risk to the Federal right and rear if the Union army moved west from Boonsboro. As Buford's division cautiously approached Funkstown via the National Road on July 10, it encountered Stuart's crescent-shaped, three-mile-long battle line, initiating the [Second] Battle of Funkstown

Battle of Funkstown

The Second Battle of Funkstown took place near Funkstown, Maryland, on July 10, 1863, during the Gettysburg Campaign of the American Civil War...

(the first being a minor skirmish on July 7 between Buford's 6th U.S. Cavalry and the 7th Virginia Cavalry of Grumble Jones's brigade). Col. Thomas C. Devin's dismounted Union cavalry brigade attacked about 8 a.m. By mid-afternoon, with Buford's cavalrymen running low on ammunition and gaining little ground, Col. Lewis A. Grant

Lewis A. Grant

Lewis Addison Grant was a teacher, lawyer, soldier in the Union Army during the American Civil War, and later Assistant U.S. Secretary of War...

's First Vermont Brigade of infantry arrived and clashed with Brig. Gen. George T. Anderson

George T. Anderson

George Thomas Anderson was a general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. Nicknamed "Tige," Anderson was noted as one of Robert E...

's Confederate brigade (commanded after Anderson's wounding at Gettysburg by Col. William W. White), the first time opposing infantry had fought since the Battle of Gettysburg. By early evening, Buford's command began withdrawing south towards Beaver Creek, where the Union I, VI, and XI Corps had concentrated.

Buford and Kilpatrick continued to hold their advance position around Boonsboro, awaiting the arrival of the Army of the Potomac. French's command sent troops to destroy the railroad bridge at Harpers Ferry and a brigade to occupied Maryland Heights, which prevented the Confederates from outflanking the lower end of South Mountain and threatening Frederick from the southwest.

Face-off at the Potomac

Littlestown, Pennsylvania

Littlestown is a borough in Adams County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 4,434 at the 2010 census.Originally laid out by Peter Klein in 1760, the town was first named "Petersburg". German settlers in the area came to call the town "Kleine Stedtle"...

, to Walkersville, Maryland

Walkersville, Maryland

Walkersville is a town in Frederick County, Maryland, United States. The population was 5,805 per the 2010 census.-History:Crum Road Bridge was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978...

. Parts of the XI Corps covered distances estimated between 30 and 34 miles from Emmitsburg to Middletown. By July 9 most of the Army of the Potomac was concentrated in a 5-mile line from Rohrersville

Rohrersville, Maryland

Rohrersville is a census-designated place in Washington County, Maryland, United States. The population was 170 at the 2000 census.-Geography:Rohrersville is located at ....

to Boonsboro. Other Union forces were in position to protect the outer flanks at Maryland Heights and at Waynesboro. Reaching these positions was difficult because of the torrential rains on July 7 that turned the roads to quagmires of mud. Long detours were required for the III and V Corps, although the disadvantage of the additional distance was offset by the roads' proximity to Frederick, which was connected by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was one of the oldest railroads in the United States and the first common carrier railroad. It came into being mostly because the city of Baltimore wanted to compete with the newly constructed Erie Canal and another canal being proposed by Pennsylvania, which...

to Union supply centers, and by the superior condition of those roads, including the macadam

Macadam

Macadam is a type of road construction pioneered by the Scotsman John Loudon McAdam in around 1820. The method simplified what had been considered state-of-the-art at that point...

ized National Road

National Road

The National Road or Cumberland Road was the first major improved highway in the United States to be built by the federal government. Construction began heading west in 1811 at Cumberland, Maryland, on the Potomac River. It crossed the Allegheny Mountains and southwestern Pennsylvania, reaching...

.

The Confederate Army's rear guard arrived in Hagerstown on the morning of July 7, screened skillfully by their cavalry, and began to establish defensive positions. By July 11 they occupied a 6-mile line on high ground with their right resting on the Potomac River near Downsville

Downsville, Maryland

Downsville is an unincorporated community not considered as a census-designated place in southwestern Washington County, Maryland, United States. It is southeast of Williamsport, Maryland on Maryland Route 63 and on Maryland Route 632 southwest of Hagerstown, Maryland...

and the left about 1.5 miles southwest of Hagerstown, covering the only road from there to Williamsport. The Conococheague Creek

Conococheague Creek

Conococheague Creek, a tributary of the Potomac River, is a free-flowing stream that originates in Pennsylvania and empties into the Potomac River near Williamsport, Maryland. It is in length, with in Pennsylvania and in Maryland...

protected the position from any attack that might be launched from the west. They erected impressive earthworks with a 6 feet (1.8 m) parapet on top and frequent gun emplacements, creating comprehensive crossfire zones. Longstreet's Corps occupied the right end of the line, Hill's the center, and Ewell's the left. These works were completed on the morning of July 12, just as the Union army arrived to confront them.

Meade telegraphed to general-in-chief Henry W. Halleck on July 12 that he intended to attack the next day, "unless something intervenes to prevent it." He once again called a council of war with his subordinates on the night of July 12. Of the seven senior officers, only Brig. Gen. James S. Wadsworth

James S. Wadsworth

James Samuel Wadsworth was a philanthropist, politician, and a Union general in the American Civil War. He was killed in battle during the Battle of the Wilderness of 1864.-Early years:...

and Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard

Oliver O. Howard

Oliver Otis Howard was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War...

were in favor of attacking the Confederate fortifications. Objections centered on the lack of reconnaissance that had been performed. On July 13, Meade and Humphreys scouted the positions personally and issued orders to the corps commanders for a reconnaissance in force on the morning of July 14. This one-day postponement was another instance of delay for which Meade's political enemies castigated him after the campaign. Halleck told Meade that it was "proverbial that councils of war never fight."

Across the Potomac

Meade's orders had stated that the reconnaissance in force by four of his corps would be started by 7 a.m. on July 14, but by this time signs were clear that the enemy had withdrawn. Advancing skirmishers found that the entrenchments were empty. Meade ordered a general pursuit of the Confederates at 8:30 a.m., but very little contact could be made at this late hour. Cavalry under Buford and Kilpatrick attacked the rearguard of Lee's army, Maj. Gen. Henry Heth

Henry Heth

Henry "Harry" Heth was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate general in the American Civil War. He is best remembered for inadvertently precipitating the Battle of Gettysburg, when he sent some of his troops of the Army of Northern Virginia to the small Pennsylvania village,...

's division, which was still on a ridge about a mile and a half from Falling Waters. The initial attack caught the Confederates by surprise after a long night with little sleep, and hand-to-hand fighting ensued. Kilpatrick attacked again and Buford struck them in their right and rear. Heth's and Pender's divisions lost as many as 2,000 men as prisoners. Brig. Gen. J. Johnston Pettigrew

J. Johnston Pettigrew

James Johnston Pettigrew was an author, lawyer, linguist, diplomat, and a Confederate general in the American Civil War...

, who had survived Pickett's Charge with a minor hand wound, was mortally wounded at Falling Waters.

The minor success against Heth did not make up for the extreme frustration in the Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

administration about allowing Lee to escape. The president was quoted by John Hay

John Hay

John Milton Hay was an American statesman, diplomat, author, journalist, and private secretary and assistant to Abraham Lincoln.-Early life:...

as saying, "We had them within our grasp. We had only to stretch forth our hands and they were ours. And nothing I could say or do could make the Army move."

Shepherdstown and Manassas Gap

Although many descriptions of the Gettysburg Campaign end with Lee's crossing of the Potomac on July 13–14, the two armies did not take up positions across from each other on the Rappahannock RiverRappahannock River

The Rappahannock River is a river in eastern Virginia, in the United States, approximately in length. It traverses the entire northern part of the state, from the Blue Ridge Mountains in the west, across the Piedmont, to the Chesapeake Bay, south of the Potomac River.An important river in American...

for almost two weeks and the official reports of the armies include the maneuvering and minor clashes along the way. On July 16 the cavalry brigades of Fitzhugh Lee and Chambliss held the fords on the Potomac at Shepherdstown

Shepherdstown, West Virginia

Shepherdstown is a town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States, located along the Potomac River. It is the oldest town in the state, having been chartered in 1762 by Colonial Virginia's General Assembly. Since 1863, Shepherdstown has been in West Virginia, and is the oldest town in...

to prevent crossing by the Federal infantry. The cavalry division under David Gregg approached the fords and the Confederates attacked them, but the Union cavalrymen held their position until dark before withdrawing. Meade called this a "spirited contest."

The Army of the Potomac crossed the Potomac River at Harpers Ferry and Berlin (now named Brunswick

Brunswick, Maryland

Brunswick is a city in Frederick County, Maryland, United States. The population was 5,870 at the 2010 census.- History :The area now known as Brunswick was originally home to the Susquehanna Indians. In 1728 the first settlement was built, and the region became known as Eel Town, because the...

) on July 17–18. They advanced along the east side of the Blue Ridge Mountains, trying to interpose themselves between Lee's army and Richmond

Richmond, Virginia

Richmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

. On July 23, Meade ordered French's III Corps to cut off the retreating Confederate columns at Front Royal

Front Royal, Virginia

Front Royal is a town in Warren County, Virginia, United States. The population was 13,589 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Warren County.-Geography:Front Royal is roughly west of Washington, D.C....

, by forcing passage through Manassas Gap

Manassas Gap

Manassas Gap is a wind gap of the Blue Ridge Mountains on the border of Fauquier County and Warren County in Virginia. At an elevation of 887 feet above sea level, it is the lowest crossing of the Blue Ridge Mountains in the state....

. At first light, French began slowly pushing Brig. Gen. James A. Walker

James A. Walker

James Alexander Walker was a Virginia lawyer, politician, and Confederate general during the American Civil War, later serving as a United States Congressman for two terms...

's brigade (the Stonewall Brigade

Stonewall Brigade

The Stonewall Brigade of the Confederate Army during the American Civil War, was a famous combat unit in United States military history. It was trained and first led by General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, a professor from Virginia Military Institute...

, part of Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson

Richard H. Anderson

Richard Heron Anderson was a career U.S. Army officer, fighting with distinction in the Mexican-American War. He also served as a Confederate general during the American Civil War, fighting in the Eastern Theater of the conflict and most notably during the 1864 Battle of Spotsylvania Court House...

's division) back into the gap. About 4:30 p.m., a strong Union attack drove Walker's men until they were reinforced by Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes

Robert E. Rodes

Robert Emmett Rodes was a railroad civil engineer and a promising young Confederate general in the American Civil War, killed in battle in the Shenandoah Valley.-Education, antebellum career:...

's division and artillery. By dusk, the poorly coordinated Union attacks were abandoned. During the night, Confederate forces withdrew into the Luray Valley. On July 24, the Union army occupied Front Royal, but Lee's army was safely beyond pursuit.

Aftermath

The retreat from Gettysburg ended the Gettysburg Campaign, Robert E. Lee's final strategic offensive in the Civil War. Afterwards, all combat operations of the Army of Northern Virginia were in reaction to Union initiatives. The Confederates suffered over 5,000 casualties during the retreat, including more than 1,000 captured at Monterey Pass, 1,000 stragglers captured from the wagon train by Gregg's division, 500 at Cunningham's Crossroads, 1,000 captured at Falling Waters, and 460 cavalrymen and 300 infantry and artillery killed, wounded, and missing during the ten days of skirmishes and battles. There were over 1,000 Union casualties—primarily cavalrymen—including losses of 263 from Kilpatrick's division at Hagerstown and 120 from Buford's division at Williamsport. For the entire campaign, Confederate casualties were approximately 27,000, Union 30,100.Meade was hampered during the retreat and pursuit not only by his alleged timidity and his willingness to defer to the cautious judgment of his subordinate commanders, but because his army was exhausted. The advance to Gettysburg was swift and tiring, followed by the largest battle of the war. The pursuit of Lee was physically demanding, through inclement weather and over difficult roads much longer than his opponent's. Enlistments expired, causing depletion of his ranks, as did the New York Draft Riots

New York Draft Riots

The New York City draft riots were violent disturbances in New York City that were the culmination of discontent with new laws passed by Congress to draft men to fight in the ongoing American Civil War. The riots were the largest civil insurrection in American history apart from the Civil War itself...

, which occupied thousands of men that could have reinforced the Army of the Potomac.

Meade was severely criticized for allowing Lee to escape, just as Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan was a major general during the American Civil War. He organized the famous Army of the Potomac and served briefly as the general-in-chief of the Union Army. Early in the war, McClellan played an important role in raising a well-trained and organized army for the Union...

had done after the Battle of Antietam

Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam , fought on September 17, 1862, near Sharpsburg, Maryland, and Antietam Creek, as part of the Maryland Campaign, was the first major battle in the American Civil War to take place on Northern soil. It was the bloodiest single-day battle in American history, with about 23,000...

. Under pressure from Lincoln, he launched two campaigns in the fall of 1863—Bristoe

Bristoe Campaign

The Bristoe Campaign was a series of minor battles fought in Virginia during October and November 1863, in the American Civil War. Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, commanding the Union Army of the Potomac, began to maneuver in an unsuccessful attempt to defeat Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern...

and Mine Run

Battle of Mine Run

The Battle of Mine Run, also known as Payne's Farm, or New Hope Church, or the Mine Run Campaign , was conducted in Orange County, Virginia, in the American Civil War....

—that attempted to defeat Lee. Both were failures. He also suffered humiliation at the hands of his political enemies in front of the Joint Congressional Committee on the Conduct of the War

United States Congress Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War

The Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War was a United States Congressional investigating committee created to handle issues surrounding the American Civil War. It was established on December 9, 1861, following the embarrassing Union defeat at the Battle of Ball's Bluff, at the instigation of...

, questioning his actions at Gettysburg and his failure to defeat Lee during the retreat to the Potomac.

Further reading

- Foote, ShelbyShelby FooteShelby Dade Foote, Jr. was an American historian and novelist who wrote The Civil War: A Narrative, a massive, three-volume history of the war. With geographic and cultural roots in the Mississippi Delta, Foote's life and writing paralleled the radical shift from the agrarian planter system of the...

. The Civil War: A NarrativeThe Civil War: A NarrativeThe Civil War: A Narrative is a three volume, 2,968-page, 1.2 million-word history of the American Civil War by Shelby Foote. Although previously known as a novelist, Foote is most famous for this non-fictional narrative history. While it touches on political and social themes, the main thrust of...

. Vol. 2, Fredericksburg to Meridian. New York: Random House, 1958. ISBN 0-394-49517-9. - Laino, Philip, Gettysburg Campaign Atlas. 2nd ed. Dayton, OH: Gatehouse Press 2009. ISBN 978-1-934900-45-1.

- Petruzzi, J. David, and Steven Stanley. The Complete Gettysburg Guide. New York: Savas Beatie, 2009. ISBN 978-1-932714-63-0.