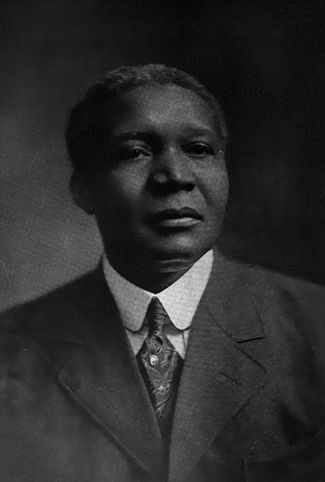

Robert Russa Moton

Encyclopedia

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

educator and author. He served as an administrator at Hampton Institute and was named principal of Tuskegee Institute in 1915 after the death of Dr. Booker T. Washington

Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington was an American educator, author, orator, and political leader. He was the dominant figure in the African-American community in the United States from 1890 to 1915...

, a position he held for 20 years until retirement in 1935.

Youth, education, family

Robert Russa Moton was born in Amelia County, VirginiaAmelia County, Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 11,400 people, 4,240 households, and 3,175 families residing in the county. The population density was 32 people per square mile . There were 4,609 housing units at an average density of 13 per square mile...

. He graduated from the Hampton Institute in 1890. He married Elizabeth Hunt Harris in 1905, but she died in 1906. He then married his second wife, Jennie Dee Booth in 1908. He had three daughters, Charlotte Moton Hubbard, a State Department Aide; Catherine Moton Patterson; and Jennie Moton Taylor.

Career, family

In 1891, he was appointed commandant of the male student cadet corps at Hampton Institute. In 1915, after the death of Dr. Booker T. Washington, he succeeded Washington as the principal of the Tuskegee Institute, a position he held until retirement in 1935. He also wrote a number of books.He attended the First Pan African Congress in Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

in 1919.

Death

Robert R. Moton died in Capahosic, in Gloucester County, VirginiaGloucester County, Virginia

Gloucester County is within the Commonwealth of Virginia in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area in the USA. Formed in 1651 in the Virginia Colony, the county was named for Henry Stuart, Duke of Gloucester, third son of King Charles I of Great Britain. Located in the Middle Peninsula region, it...

in 1940 at age 73.

Tuskegee

Moton FieldTuskegee Airmen National Historic Site

Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site, at Moton Field in Tuskegee, Alabama, commemorates the contributions of African American airmen in World War II. Moton Field was the site of primary flight training for the pioneering pilots known as the Tuskegee Airmen. It was constructed in 1941 as a new...

, the initial training base for the Tuskegee Airmen

Tuskegee Airmen

The Tuskegee Airmen is the popular name of a group of African American pilots who fought in World War II. Formally, they were the 332nd Fighter Group and the 477th Bombardment Group of the U.S. Army Air Corps....

was named after him.

Holly Knoll

Holly Knoll, the retirement home in which he lived in Gloucester County, was named a U.S. National Historic Landmark in 1981, termed the Robert R. Moton House.R.R. Moton High School, Museum in Farmville, Virginia

Near his birthplace in adjacent Amelia County, the all-black R. R. Moton High School, named for him, was located in the town of FarmvilleFarmville, Virginia

Farmville is a town in Prince Edward and Cumberland counties in the U.S. state of Virginia. The population was 6,845 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Prince Edward County....

in Prince Edward County

Prince Edward County, Virginia

Prince Edward County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of 2010, the population was 23,368. Its county seat is Farmville.-Formation and County Seats:...

. This became a dubious distinction as the conditions there deteriorated due to inequities in funding for the segregated schools by the County School Board and the County Board of Supervisors.

The school did not have a gymnasium, cafeteria, or teachers' restrooms. Due to overcrowding, three plywood buildings had been erected and some students had to take classes in an immobile school bus parked outside. Teachers and students did not have desks or blackboards, The school's requests for additional funds were denied by the all-white school board. In 1951, students staged a walkout protesting the conditions. The NAACP took up their case, however, only when the students—by a one vote margin—agreed to seek an integrated school rather than improved conditions at their black school. Then, Howard University

Howard University

Howard University is a federally chartered, non-profit, private, coeducational, nonsectarian, historically black university located in Washington, D.C., United States...

-trained attorneys Spotswood W. Robinson and Oliver Hill

Oliver Hill

Oliver White Hill, Sr. was a civil rights attorney from Richmond, Virginia. His work against racial discrimination helped end the doctrine of "separate but equal." He also helped win landmark legal decisions involving equality in pay for black teachers, access to school buses, voting rights, jury...

filed suit.

In Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County

Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County

Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County was one of the five cases combined into Brown v. Board of Education, the famous case in which the U.S. Supreme Court, in 1954, officially overturned racial segregation in U.S. public schools...

, a state court rejected the suit, agreeing with defense attorney T. Justin Moore that Virginia was vigorously equalizing black and white schools. The verdict was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Subsequently, it was one of five incorporated into Brown v. Board of Education

Brown v. Board of Education

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 , was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students unconstitutional. The decision overturned the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 which...

, the landmark case which overturned school segregation in the United States.

As a result of the Brown decision, in 1959 the Board of Supervisors for Prince Edward County refused to appropriate any funds for the County School Board at all, effectively closing all public schools rather than integrate them. Prince Edward County Public Schools remained closed for five years.

A new entity, the Prince Edward Foundation, created a series of private schools to educate the county's white children. These schools were supported by tuition grants from the state and tax credits from the county. Prince Edward Academy, the all-white private, was one of the first such schools in Virginia which came to be called segregation academies.

Black students had to go to school elsewhere or forgo their education altogether. Some got schooling with relatives in nearby communities or at makeshift schools in church basements. Others were educated out of state by groups such as the Society of Friends. In 1963–64, the NAACP-sponsored Prince Edward Free School picked up some of the slack. But some pupils missed part or all of their education for five years.

When the public schools finally reopened in 1964, they were fully integrated. Historians mark that event as the end of Massive Resistance

Massive resistance

Massive resistance was a policy declared by U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd, Sr. on February 24, 1956, to unite other white politicians and leaders in Virginia in a campaign of new state laws and policies to prevent public school desegregation after the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision...

in Virginia.

In modern times, Prince Edward County Public Schools now operates single Elementary, Middle, and High Schools for all students, regardless of race. They are:

- Prince Edward Elementary School

- Prince Edward Middle School

- Prince Edward High School

Many of the segregation academies eventually closed; others changed their mission, and eliminated discriminatory policies. Prince Edward Academy was one of these, and was renamed the Fuqua School

Fuqua School

Fuqua School is a private primary and secondary school located in Farmville, Virginia. It is named after J.B. Fuqua, who made a large contribution to the school in 1992 to save it from financial insolvency...

.

The former R.R. Moton High School building is now a community landmark. In 1998, it was named a National Historic Site

National Historic Sites (United States)

National Historic Sites are protected areas of national historic significance in the United States. A National Historic Site usually contains a single historical feature directly associated with its subject...

, and it now houses the Robert Russa Moton Museum

Robert Russa Moton Museum

Robert Russa Moton Museum in the town of Farmville in Prince Edward County, Virginia is a museum which serves as a center for the study of civil rights in education.It is housed in the former R. R...

, a center for the study of civil rights

Civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from unwarranted infringement by governments and private organizations, and ensure one's ability to participate in the civil and political life of the state without discrimination or repression.Civil rights include...

in education.

Public service

Moton became involved in various aspects of public service.- 1918, Traveled to France at the request of President Woodrow WilsonWoodrow WilsonThomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

to inspect black troops stationed there by the United StatesUnited StatesThe United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

. - 1923, Played a leading role in the establishment of the Veterans Administration Hospital for Negroes, Tuskegee, AlabamaTuskegee, AlabamaTuskegee is a city in Macon County, Alabama, United States. At the 2000 census the population was 11,846 and is designated a Micropolitan Statistical Area. Tuskegee has been an important site in various stages of African American history....

. - 1927, Chairman of the American National Red Cross, Colored Advisory Commission on the Great Mississippi FloodGreat Mississippi Flood of 1927The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 was the most destructive river flood in the history of the United States.-Events:The flood began when heavy rains pounded the central basin of the Mississippi in the summer of 1926. By September, the Mississippi's tributaries in Kansas and Iowa were swollen to...

. - 1932, Chairman of the United States Commission on Education in Haiti.

There is an elementary school named Robert R. Moton in Hampton, VA; also in Miami FL, Westminster, Md and New Orleans, LA.

Publications

- Some Elements Necessary To Race Development, 1913.

- Racial Good Will Addresses, 1916.

- Negro of Today: Remarkable Growth Of Fifty Years, 1921.

- Negros Debt to Lincoln, 1922.

- Frissell the Builder: Address at the Dedication of the Frissell Memorial Organ in Ogden Hall, Hampton Institute, 1923.

- Finding A Way Out (autobiography). Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Page & Co, 1920. ISBN 0-8371-1897-2

- What the Negro Thinks. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1929.

Further reading

- Spangler, Michael (1996). The Moton Family: A Register of Its Papers in the Library of Congress. Washington: Library of Congress.

External links

- The Gloucester Institute

- Finding a Way Out: An Autobiography. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1921, c1920.

- Robert Russa Moton Museum, Farmville, Virginia

- Dr. Robert Russa Moton Award