Robert Stephenson

Encyclopedia

Robert Stephenson FRS (16 October 1803 – 12 October 1859) was an English

civil engineer

. He was the only son of George Stephenson

, the famed locomotive

builder and railway

engineer

; many of the achievements popularly credited to his father were actually the joint efforts of father and son.

, east of Newcastle Upon Tyne

, the only son of George Stephenson and his wife, Fanny. At the time, George and Fanny were living in a single room and George was working as a brakesman on a stationary colliery engine. In 1804, the family moved to a cottage in West Moor when George was made brakeman at West Moor Colliery. In 1805 Fanny gave birth to a daughter who died after a few weeks. The next year Robert’s mother died of consumption. George then went and worked in Scotland for a short time, leaving the infant Robert with a local woman. However, George soon returned to West Moor, and his sister Nelly came to live at the cottage to look after Robert.

George had received virtually no formal education and he was determined that his son would have the education that he lacked. At a young age, George expected Robert to read books that were extremely difficult and learn how to read technical drawings. Father and son studied together in the evenings, improving George’s understanding of science as well as Robert’s. They also built a sundial together, which they placed above the front door of their cottage. The cottage subsequently became known as Dial Cottage and is preserved today as a monument to them. Because of his great aptitude for engineering, George was promoted in 1812 to be an enginewright at Killingworth Colliery

, a skilled job with responsibility for the maintenance and repair of the colliery machinery. His wages were therefore much improved. Robert was sent to a two-room primary school run by Mr and Mrs Rutter in Longbenton, near Killingworth until the age of eleven. George's success in locomotive engineering gave him the ability to enroll Robert in a private academy. He was then sent to Doctor Bruce’s Academy in Percy Street, Newcastle. This was a private institution and Robert would have been studying alongside the children of well-off families. Surprisingly his fellow pupils failed to see any remarkable signs of talent. Whilst at the Academy, Robert became a reading member of the nearby Literary and Philosophical Society. Robert had minimal education compared to today's engineers, but proved to be a very successful engineer.

, the manager of Killingworth Colliery

, and a period at the University of Edinburgh

where he met George Parker Bidder

, Robert went to work with his father on his railway projects, the first being the Stockton and Darlington Railway. In 1823, when he was 20, Robert set up a company in partnership with his father, Michael Longridge and Edward Pease

to build railway locomotives. On an early trade card, Robert Stephenson & Co were described as "Engineers, Millwrights & Machinists, Brass & Iron Founders. After six months of education from Edinburgh, Stephenson was able to manage his newly established firm of Robert Stephenson and Company

, which was situated in South Street, off Forth Street in Newcastle. The works, known as the Forth Street Works, were the first locomotive works in the world, and it was here that the locomotives for the Stockton and Darlington Railway were built. The first locomotives produced there were called Locomotion No 1

, Hope, Diligence and Black Diamond. The Forth Street works continued to build locomotives until the mid-twentieth century, and the original factory building still exists, at Forth Street in Newcastle, as the Robert Stephenson Centre. George used Locomotion in 1825 for the opening of the Stockton and Darlington line, which Robert had helped to survey.

In 1824, a year before the Stockton and Darlington line opened, Robert went off to South America for three years, to work as an engineer in the Colombian gold mines. His decision seems unusual, and there have been suggestions that it was caused by a rift with his father, but there is no evidence of this. When he returned in 1827, his father was building the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

. George was living in Liverpool directing proceedings, so Robert took charge at the Forth Street Works and worked on the development of a locomotive to compete in the forthcoming Rainhill Trials

, intended to choose a locomotive design to be used on the new railway. The result was the Rocket

, which had a multi-tubular boiler to obtain maximum steam pressure from the exhaust gases. Rocket competed successfully in the Rainhill Trials, none of its competitors completing the trial. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway opened in 1830, with a procession of eight trains setting out from Liverpool. George led the parade driving the Northumbrian

, Robert drove the Phoenix and Joseph Locke drove the Rocket. Following its success, the company built locomotives for other newly-established railways, including the Leicester and Swannington Railway

. It became necessary to extend the Forth Street Works to accommodate the increased work.

On 17 June 1829, Robert married Frances Sanderson in London. The couple went to live at 5 Greenfield Place, off Westgate Road in Newcastle. Unfortunately they were not married long. In 1842, Robert’s wife, Fanny as she was known, died. They had no children and Robert never re-married.

In 1830, Robert designed Planet

, a much more advanced locomotive than Rocket. Stephenson’s company was experiencing stiff competition from other locomotive manufacturers. Up until then, locomotives had their cylinders placed outside the wheels, as this was the easiest arrangement. It was thought that, placing the cylinders inside the wheels was a more efficient arrangement and this was done on Planet. However there was thought to be an increased risk of broken crank axles. There was friction between Robert and his father over this question. The locomotive, when completed, was found to produce much more power than previous designs. It was used on the Camden and Amboy Railway in the USA.

In 1833 Robert was given the post of Chief Engineer for the London and Birmingham Railway

, the first main-line railway to enter London

, and the initial section of the West Coast Main Line

. That same year Robert and Frances moved to London to live. The new line posed a number of difficult civil engineering challenges, most notably Kilsby Tunnel

, and was completed in 1838. Stephenson was directly responsible for the tunnel under Primrose Hill

, which required excavation by shafts. Early locomotives could not manage the climb from Euston Station

to Chalk Farm

, requiring Stephenson to devise a system that would draw them up the hill by chains using a steam engine near The Roundhouse

. This impressive structure remains in use today as an Arts Centre. The London and Birmingham Railway was completed at an enormous cost of £5.5 million, compared with the cost of £900,000 for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.

In 1838, he was summoned to Tuscany by Emanuele Fenzi

and Pietro Senn to direct the works for the Leopolda railway. The success attained in this first Tuscan experiment in railways led the Russian princes Anatolio Demidoff and Giuseppe Poniatowski to commission Stephenson to construct a railway to Forlì, passing through the Muraglione Pass. Although this railway was not built, it was to all effects the first project for what was to become, almost forty years later, the Faentina railway.

Robert Stephenson constructed a number of well-known bridges to carry the new railway lines, following the experience of his father on the Stockton and Darlington line. George Stephenson built the famous Gaunless bridge (which was dismantled and reassembled and is now in the York Railway Museum Car Park) for example, a very early cast iron

Robert Stephenson constructed a number of well-known bridges to carry the new railway lines, following the experience of his father on the Stockton and Darlington line. George Stephenson built the famous Gaunless bridge (which was dismantled and reassembled and is now in the York Railway Museum Car Park) for example, a very early cast iron

structure, as well as the many bridges needed for the Liverpool and Manchester line opened in 1830. In 1850 the railway from London to Scotland via Newcastle was completed. This required new bridges for both the Tyne and the Tweed and he designed them both. He designed the High Level Bridge

, at Newcastle upon Tyne as a two-deck bridge supported on tall stone columns. Rail traffic was carried on the upper deck and road traffic on the lower deck. Queen Victoria opened the bridge in 1849. Stephenson also designed the Royal Border Bridge

over the Tweed for the same line. It was an imposing viaduct of 28 arches and was opened by Queen Victoria in 1850. At last the railway ran all the way from London to Edinburgh. In the same year Stephenson and William Fairbairn

's, Britannia Bridge

across the Menai Strait

, was opened. This bridge had the novel design of wrought-iron box-section tubes to carry railway line inside them, because a tubular design using wrought-iron gave the greatest strength and flexibility. The Conwy railway bridge

between Llandudno Junction

and Conwy

was built in 1848 using a similar design. The Conway and Britannia bridges were such a success that Stephenson applied the design to other bridges, two in Egypt, and the 6,588 feet long Victoria Bridge

over the St Lawrence River at Montreal in Canada. This was built as one long tube made up of 25 sections. The design was rarely used owing to the cost, and few now remain, the best preserved being the Conwy bridge, which is still used by trains. Other bridges include, Arnside Viaduct in Cumbria

, and a joint road and rail bridge in 1850 over the River Nene

, at Sutton Bridge

in Lincolnshire

.

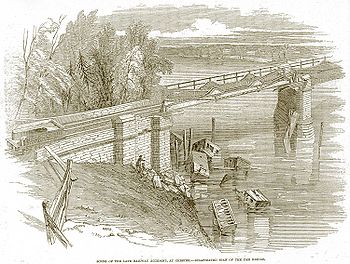

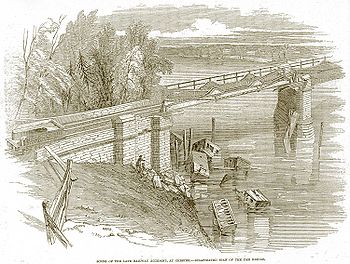

One of Stephenson's few failures was his design of the Dee bridge, which collapsed

under a train. Five people were killed. He was heavily criticized for the design, even before the collapse, particularly for the poor choice of materials, which included cast iron

. In fact, he had used cast iron for bridge designs before, as had Brunel

, but in this case he used longer girders (98 ft) than used previously and their great length contributed to the failure. Stephenson had to give evidence at the inquest and this proved to be a harrowing experience. Fellow engineers such as Joseph Locke

and Brunel

who were called as witnesses at the consequent enquiry refused to criticise Stephenson, even though they rarely used cast iron themselves. A large number of similar bridges had to be demolished and rebuilt to safer designs.

to Alès

. He made journeys to Spain to advise on the construcition of the Railway from the Bay of Biscay

to Madrid

and visited the line Orléans

- Tours

. On Prosper Enfantin's initiative, he and Talabot and Alois Negrelli

became members of the Société d'Études du canal de Suez in 1846, where they studied the feasibility of the Suez canal

. In late 1850, he was called by the Swiss Federal Council

to advise on the future Swiss railway net and its financial implications. From 1851 to 1853, he built the railway from Alexandria

to Cairo

, which was extended to Suez

in 1858.

He served as Conservative

He served as Conservative

Member of Parliament

for Whitby

from 1847 until his death. Within the Tory

party, he sat on right-wing , at that time hostile to free trade , and Stephenson appeared anxious to avoid change in almost any form . He was a commissioner of the short-lived London Metropolitan Commission of Sewers

from 1848. He was President of the Institution of Civil Engineers

, for two years from 1855.

Robert’s father George died in 1848 aged 67. Robert died on 12 October 1859 at his London home aged 55. Brunel

had died one month earlier on 15 September 1859. Robert was buried in Westminster Abbey

next to Thomas Telford

. Queen Victoria gave special permission for the cortege to pass through Hyde Park and 3,000 tickets were sold to spectators. In his eulogy, he was called ‘the greatest engineer of the present century’. In his will he left nearly £400,000 .

Stephenson was well respected by his engineering peers and had a lifetime friendship with Joseph Locke

, a rival engineer during his career a fact reflected in Locke being a pallbearer at his funeral . Another such friendship was with Isambard Kingdom Brunel

, who often helped Stephenson on various projects , as did Stephenson for Brunel. The two were however diametrically opposed on one issue: that of Brunel’s advocacy of atmospheric railway

s; trains without a locomotive, driven by a piston sliding inside an evacuated pipe mounted between the rails. The pipe was to be kept evacuated by stationary steam-driven pumps at intervals along the railway, and Stephenson was convinced that the idea could not work. After Brunel's proposal was piloted on a small scale and proved unworkable, Stephenson was proven right.

The Stephenson Railway Museum

in North Shields

is named after George and Robert Stephenson.

He was god-father to Robert Baden-Powell, whose full name was Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, the first two in honour of his godfather, the third his mother's maiden name.

film

Steamboy

, in that world

having apparently lived until 1866. In the English dub of the film his character also speaks with a rather posh stereotypical English accent and not the northern tones Stephenson used. (In fact, the first biography of Stephenson, by J. C. Jeaffreson, makes clear that Stephenson went to some trouble to lose "the diction, idiom or intonation of North-country dialect". See Jeaffreson, "The Life of Robert Stephenson, FRS," (1864) vol. 1, page 77.)

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

civil engineer

Civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering; the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructures while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing infrastructures that have been neglected.Originally, a...

. He was the only son of George Stephenson

George Stephenson

George Stephenson was an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer who built the first public railway line in the world to use steam locomotives...

, the famed locomotive

Locomotive

A locomotive is a railway vehicle that provides the motive power for a train. The word originates from the Latin loco – "from a place", ablative of locus, "place" + Medieval Latin motivus, "causing motion", and is a shortened form of the term locomotive engine, first used in the early 19th...

builder and railway

Rail transport

Rail transport is a means of conveyance of passengers and goods by way of wheeled vehicles running on rail tracks. In contrast to road transport, where vehicles merely run on a prepared surface, rail vehicles are also directionally guided by the tracks they run on...

engineer

Engineer

An engineer is a professional practitioner of engineering, concerned with applying scientific knowledge, mathematics and ingenuity to develop solutions for technical problems. Engineers design materials, structures, machines and systems while considering the limitations imposed by practicality,...

; many of the achievements popularly credited to his father were actually the joint efforts of father and son.

Early life

He was born on the 16th of October, 1803, at Willington QuayWillington Quay

Willington Quay is an area in the borough of North Tyneside in Tyne and Wear in northern England. It is situated on the north bank of the River Tyne, facing Jarrow, and between Wallsend and North Shields. It is served by the Howdon Metro station in Howdon. The area from 2006 onwards has been an...

, east of Newcastle Upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne is a city and metropolitan borough of Tyne and Wear, in North East England. Historically a part of Northumberland, it is situated on the north bank of the River Tyne...

, the only son of George Stephenson and his wife, Fanny. At the time, George and Fanny were living in a single room and George was working as a brakesman on a stationary colliery engine. In 1804, the family moved to a cottage in West Moor when George was made brakeman at West Moor Colliery. In 1805 Fanny gave birth to a daughter who died after a few weeks. The next year Robert’s mother died of consumption. George then went and worked in Scotland for a short time, leaving the infant Robert with a local woman. However, George soon returned to West Moor, and his sister Nelly came to live at the cottage to look after Robert.

George had received virtually no formal education and he was determined that his son would have the education that he lacked. At a young age, George expected Robert to read books that were extremely difficult and learn how to read technical drawings. Father and son studied together in the evenings, improving George’s understanding of science as well as Robert’s. They also built a sundial together, which they placed above the front door of their cottage. The cottage subsequently became known as Dial Cottage and is preserved today as a monument to them. Because of his great aptitude for engineering, George was promoted in 1812 to be an enginewright at Killingworth Colliery

Killingworth

Killingworth, formerly Killingworth Township, is a town north of Newcastle Upon Tyne, in North Tyneside, United Kingdom.Built as a planned town in the 1960s, most of Killingworth's residents commute to Newcastle, or the city's surrounding area. However, Killingworth itself has a sizeable...

, a skilled job with responsibility for the maintenance and repair of the colliery machinery. His wages were therefore much improved. Robert was sent to a two-room primary school run by Mr and Mrs Rutter in Longbenton, near Killingworth until the age of eleven. George's success in locomotive engineering gave him the ability to enroll Robert in a private academy. He was then sent to Doctor Bruce’s Academy in Percy Street, Newcastle. This was a private institution and Robert would have been studying alongside the children of well-off families. Surprisingly his fellow pupils failed to see any remarkable signs of talent. Whilst at the Academy, Robert became a reading member of the nearby Literary and Philosophical Society. Robert had minimal education compared to today's engineers, but proved to be a very successful engineer.

Locomotive designer

After his education at the Bruce Academy, an apprenticeship to Nicholas WoodNicholas Wood

Nicholas Wood was an English colliery and steam locomotive engineer. He helped engineer and design many steps forward in both engineering and mining safety, and helped bring about the North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers, holding the position of President from its...

, the manager of Killingworth Colliery

Killingworth

Killingworth, formerly Killingworth Township, is a town north of Newcastle Upon Tyne, in North Tyneside, United Kingdom.Built as a planned town in the 1960s, most of Killingworth's residents commute to Newcastle, or the city's surrounding area. However, Killingworth itself has a sizeable...

, and a period at the University of Edinburgh

University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh, founded in 1583, is a public research university located in Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland, and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The university is deeply embedded in the fabric of the city, with many of the buildings in the historic Old Town belonging to the university...

where he met George Parker Bidder

George Parker Bidder

George Parker Bidder was an English engineer, architect and calculating prodigy.Born in the town of Moretonhampstead, Devon, England, he displayed a natural skill at calculation from an early age...

, Robert went to work with his father on his railway projects, the first being the Stockton and Darlington Railway. In 1823, when he was 20, Robert set up a company in partnership with his father, Michael Longridge and Edward Pease

Edward Pease (1767-1858)

Edward Pease , a woollen manufacturer from Darlington, England, was the main promoter of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, which opened in 1825.-Background and education:...

to build railway locomotives. On an early trade card, Robert Stephenson & Co were described as "Engineers, Millwrights & Machinists, Brass & Iron Founders. After six months of education from Edinburgh, Stephenson was able to manage his newly established firm of Robert Stephenson and Company

Robert Stephenson and Company

Robert Stephenson and Company was a locomotive manufacturing company founded in 1823. It was the first company set up specifically to build railway engines.- Foundation and early success :...

, which was situated in South Street, off Forth Street in Newcastle. The works, known as the Forth Street Works, were the first locomotive works in the world, and it was here that the locomotives for the Stockton and Darlington Railway were built. The first locomotives produced there were called Locomotion No 1

Locomotion No 1

Locomotion No. 1 is an early British steam locomotive. Built by George and Robert Stephenson's company Robert Stephenson and Company in 1825, it hauled the first train on the Stockton and Darlington Railway on 27 September 1825....

, Hope, Diligence and Black Diamond. The Forth Street works continued to build locomotives until the mid-twentieth century, and the original factory building still exists, at Forth Street in Newcastle, as the Robert Stephenson Centre. George used Locomotion in 1825 for the opening of the Stockton and Darlington line, which Robert had helped to survey.

In 1824, a year before the Stockton and Darlington line opened, Robert went off to South America for three years, to work as an engineer in the Colombian gold mines. His decision seems unusual, and there have been suggestions that it was caused by a rift with his father, but there is no evidence of this. When he returned in 1827, his father was building the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

Liverpool and Manchester Railway

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was the world's first inter-city passenger railway in which all the trains were timetabled and were hauled for most of the distance solely by steam locomotives. The line opened on 15 September 1830 and ran between the cities of Liverpool and Manchester in North...

. George was living in Liverpool directing proceedings, so Robert took charge at the Forth Street Works and worked on the development of a locomotive to compete in the forthcoming Rainhill Trials

Rainhill Trials

The Rainhill Trials were an important competition in the early days of steam locomotive railways, run in October 1829 in Rainhill, Lancashire for the nearly completed Liverpool and Manchester Railway....

, intended to choose a locomotive design to be used on the new railway. The result was the Rocket

Stephenson's Rocket

Stephenson's Rocket was an early steam locomotive of 0-2-2 wheel arrangement, built in Newcastle Upon Tyne at the Forth Street Works of Robert Stephenson and Company in 1829.- Design innovations :...

, which had a multi-tubular boiler to obtain maximum steam pressure from the exhaust gases. Rocket competed successfully in the Rainhill Trials, none of its competitors completing the trial. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway opened in 1830, with a procession of eight trains setting out from Liverpool. George led the parade driving the Northumbrian

Northumbrian (locomotive)

Northumbrian was an early steam locomotive built by Robert Stephenson in 1830 and used at the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. It was the last of Stephenson's 0-2-2 locomotives in the style of Rocket, but it introduced several innovations...

, Robert drove the Phoenix and Joseph Locke drove the Rocket. Following its success, the company built locomotives for other newly-established railways, including the Leicester and Swannington Railway

Leicester and Swannington Railway

The Leicester and Swannington Railway was one of England's first railways, being opened on 17 July 1832 to bring coal from collieries in west Leicestershire to Leicester.-Overview:...

. It became necessary to extend the Forth Street Works to accommodate the increased work.

On 17 June 1829, Robert married Frances Sanderson in London. The couple went to live at 5 Greenfield Place, off Westgate Road in Newcastle. Unfortunately they were not married long. In 1842, Robert’s wife, Fanny as she was known, died. They had no children and Robert never re-married.

In 1830, Robert designed Planet

Planet (locomotive)

Planet was an early steam locomotive built in 1830 by Robert Stephenson and Company for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. The ninth locomotive built for the L&MR, it was Stephenson's next major design change after the Rocket. It was the first locomotive to employ inside cylinders, and...

, a much more advanced locomotive than Rocket. Stephenson’s company was experiencing stiff competition from other locomotive manufacturers. Up until then, locomotives had their cylinders placed outside the wheels, as this was the easiest arrangement. It was thought that, placing the cylinders inside the wheels was a more efficient arrangement and this was done on Planet. However there was thought to be an increased risk of broken crank axles. There was friction between Robert and his father over this question. The locomotive, when completed, was found to produce much more power than previous designs. It was used on the Camden and Amboy Railway in the USA.

In 1833 Robert was given the post of Chief Engineer for the London and Birmingham Railway

London and Birmingham Railway

The London and Birmingham Railway was an early railway company in the United Kingdom from 1833 to 1846, when it became part of the London and North Western Railway ....

, the first main-line railway to enter London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, and the initial section of the West Coast Main Line

West Coast Main Line

The West Coast Main Line is the busiest mixed-traffic railway route in Britain, being the country's most important rail backbone in terms of population served. Fast, long-distance inter-city passenger services are provided between London, the West Midlands, the North West, North Wales and the...

. That same year Robert and Frances moved to London to live. The new line posed a number of difficult civil engineering challenges, most notably Kilsby Tunnel

Kilsby Tunnel

The Kilsby Tunnel is a railway tunnel on the West Coast Main Line railway in England. It was designed and engineered by Robert Stephenson.The tunnel is located near the village of Kilsby in Northamptonshire roughly 5 miles south-east of Rugby and is long.The tunnel was opened in 1838 as a part of...

, and was completed in 1838. Stephenson was directly responsible for the tunnel under Primrose Hill

Primrose Hill

Primrose Hill is a hill of located on the north side of Regent's Park in London, England, and also the name for the surrounding district. The hill has a clear view of central London to the south-east, as well as Belsize Park and Hampstead to the north...

, which required excavation by shafts. Early locomotives could not manage the climb from Euston Station

Euston railway station

Euston railway station, also known as London Euston, is a central London railway terminus in the London Borough of Camden. It is the sixth busiest rail terminal in London . It is one of 18 railway stations managed by Network Rail, and is the southern terminus of the West Coast Main Line...

to Chalk Farm

Chalk Farm

Chalk Farm is an area of north London, England. It lies directly to the north of Camden Town and its underground station is the closest tube station to the nearby, upmarket neighbourhood of Primrose Hill....

, requiring Stephenson to devise a system that would draw them up the hill by chains using a steam engine near The Roundhouse

The Roundhouse

The Roundhouse is a Grade II* listed former railway engine shed in Chalk Farm, London, England, which has been converted into a performing arts and concert venue. It was originally built in 1847 as a roundhouse , a circular building containing a railway turntable, but was only used for railway...

. This impressive structure remains in use today as an Arts Centre. The London and Birmingham Railway was completed at an enormous cost of £5.5 million, compared with the cost of £900,000 for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.

In 1838, he was summoned to Tuscany by Emanuele Fenzi

Emanuele Fenzi

Emanuele Fenzi , was an Italian a leading banker, iron producer, concessionaire of the Livorno–Florence railway and other railway enterprises, merchant for exportation of Tuscan products, and landowner...

and Pietro Senn to direct the works for the Leopolda railway. The success attained in this first Tuscan experiment in railways led the Russian princes Anatolio Demidoff and Giuseppe Poniatowski to commission Stephenson to construct a railway to Forlì, passing through the Muraglione Pass. Although this railway was not built, it was to all effects the first project for what was to become, almost forty years later, the Faentina railway.

Bridge builder

Cast iron

Cast iron is derived from pig iron, and while it usually refers to gray iron, it also identifies a large group of ferrous alloys which solidify with a eutectic. The color of a fractured surface can be used to identify an alloy. White cast iron is named after its white surface when fractured, due...

structure, as well as the many bridges needed for the Liverpool and Manchester line opened in 1830. In 1850 the railway from London to Scotland via Newcastle was completed. This required new bridges for both the Tyne and the Tweed and he designed them both. He designed the High Level Bridge

High Level Bridge

The High Level Bridge is a road and railway bridge spanning the River Tyne between Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead in North East England.-Design:...

, at Newcastle upon Tyne as a two-deck bridge supported on tall stone columns. Rail traffic was carried on the upper deck and road traffic on the lower deck. Queen Victoria opened the bridge in 1849. Stephenson also designed the Royal Border Bridge

Royal Border Bridge

Royal Border Bridge spans the River Tweed between Berwick-upon-Tweed and Tweedmouth in Northumberland, England. It is a Grade I listed railway viaduct built between 1847 and 1850, when it was opened by Queen Victoria. The engineer who designed it was Robert Stephenson...

over the Tweed for the same line. It was an imposing viaduct of 28 arches and was opened by Queen Victoria in 1850. At last the railway ran all the way from London to Edinburgh. In the same year Stephenson and William Fairbairn

William Fairbairn

Sir William Fairbairn, 1st Baronet was a Scottish civil engineer, structural engineer and shipbuilder.-Early career:...

's, Britannia Bridge

Britannia Bridge

Britannia Bridge is a bridge across the Menai Strait between the island of Anglesey and the mainland of Wales. It was originally designed and built by Robert Stephenson as a tubular bridge of wrought iron rectangular box-section spans for carrying rail traffic...

across the Menai Strait

Menai Strait

The Menai Strait is a narrow stretch of shallow tidal water about long, which separates the island of Anglesey from the mainland of Wales.The strait is bridged in two places - the main A5 road is carried over the strait by Thomas Telford's elegant iron suspension bridge, the first of its kind,...

, was opened. This bridge had the novel design of wrought-iron box-section tubes to carry railway line inside them, because a tubular design using wrought-iron gave the greatest strength and flexibility. The Conwy railway bridge

Conwy Railway Bridge

Conwy railway bridge carries the North Wales coast railway line across the River Conwy between Llandudno Junction and the town of Conwy. The wrought iron tubular bridge was built by Robert Stephenson to a design by William Fairbairn, and is similar in construction to Stephenson's other famous...

between Llandudno Junction

Llandudno Junction

Llandudno Junction , once known as Tremarl, is a small town in the county borough of Conwy, Wales. It is part of the ancient parish of Llangystennin, and it is located south of Llandudno. It adjoins Deganwy and is to the east of the walled town of Conwy, which is on the opposite side of the River...

and Conwy

Conwy

Conwy is a walled market town and community in Conwy County Borough on the north coast of Wales. The town, which faces Deganwy across the River Conwy, formerly lay in Gwynedd and prior to that in Caernarfonshire. Conwy has a population of 14,208...

was built in 1848 using a similar design. The Conway and Britannia bridges were such a success that Stephenson applied the design to other bridges, two in Egypt, and the 6,588 feet long Victoria Bridge

Victoria Bridge (Montreal)

Victoria Bridge , formerly originally known as Victoria Jubilee Bridge, is a bridge over the St. Lawrence River, linking Montreal, Quebec, to the south shore city of Saint-Lambert....

over the St Lawrence River at Montreal in Canada. This was built as one long tube made up of 25 sections. The design was rarely used owing to the cost, and few now remain, the best preserved being the Conwy bridge, which is still used by trains. Other bridges include, Arnside Viaduct in Cumbria

Cumbria

Cumbria , is a non-metropolitan county in North West England. The county and Cumbria County Council, its local authority, came into existence in 1974 after the passage of the Local Government Act 1972. Cumbria's largest settlement and county town is Carlisle. It consists of six districts, and in...

, and a joint road and rail bridge in 1850 over the River Nene

River Nene

The River Nene is a river in the east of England that rises from three sources in the county of Northamptonshire. The tidal river forms the border between Cambridgeshire and Norfolk for about . It is the tenth longest river in the United Kingdom, and is navigable for from Northampton to The...

, at Sutton Bridge

Sutton Bridge

Sutton Bridge is a village and civil parish in southeastern Lincolnshire, England on the west bank of the River Nene in the district of South Holland.-Geography:...

in Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire is a county in the east of England. It borders Norfolk to the south east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south west, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire to the west, South Yorkshire to the north west, and the East Riding of Yorkshire to the north. It also borders...

.

One of Stephenson's few failures was his design of the Dee bridge, which collapsed

Dee bridge disaster

The Dee bridge disaster was a rail accident that occurred on 24 May 1847 in Chester with five fatalities.A new bridge across the River Dee was needed for the Chester and Holyhead Railway, a project planned in the 1840s for the expanding British railway system. It was built using cast iron girders,...

under a train. Five people were killed. He was heavily criticized for the design, even before the collapse, particularly for the poor choice of materials, which included cast iron

Cast iron

Cast iron is derived from pig iron, and while it usually refers to gray iron, it also identifies a large group of ferrous alloys which solidify with a eutectic. The color of a fractured surface can be used to identify an alloy. White cast iron is named after its white surface when fractured, due...

. In fact, he had used cast iron for bridge designs before, as had Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, FRS , was a British civil engineer who built bridges and dockyards including the construction of the first major British railway, the Great Western Railway; a series of steamships, including the first propeller-driven transatlantic steamship; and numerous important bridges...

, but in this case he used longer girders (98 ft) than used previously and their great length contributed to the failure. Stephenson had to give evidence at the inquest and this proved to be a harrowing experience. Fellow engineers such as Joseph Locke

Joseph Locke

Joseph Locke was a notable English civil engineer of the 19th century, particularly associated with railway projects...

and Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, FRS , was a British civil engineer who built bridges and dockyards including the construction of the first major British railway, the Great Western Railway; a series of steamships, including the first propeller-driven transatlantic steamship; and numerous important bridges...

who were called as witnesses at the consequent enquiry refused to criticise Stephenson, even though they rarely used cast iron themselves. A large number of similar bridges had to be demolished and rebuilt to safer designs.

International activities

Robert Stephenson's advice on railway matters was sought after in various countries. In France, he advised his friend and French engineer Paulin Talabot during the years 1837 to 1840 on the construction of the Chemins de fer du Gard from BeaucaireBeaucaire

Beaucaire is a commune in the Gard department in Languedoc-Roussillon in southern France.-Geography:Beaucaire is located on the Rhône River, opposite the town of Tarascon, which is in Bouches-du-Rhône department of Provence.Neighboring communes:...

to Alès

Alès

Alès is a commune in the Gard department in the Languedoc-Roussillon region in southern France. It is one of the sub-prefectures of the department. It was formerly known as Alais.-Geography:...

. He made journeys to Spain to advise on the construcition of the Railway from the Bay of Biscay

Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay is a gulf of the northeast Atlantic Ocean located south of the Celtic Sea. It lies along the western coast of France from Brest south to the Spanish border, and the northern coast of Spain west to Cape Ortegal, and is named in English after the province of Biscay, in the Spanish...

to Madrid

Madrid

Madrid is the capital and largest city of Spain. The population of the city is roughly 3.3 million and the entire population of the Madrid metropolitan area is calculated to be 6.271 million. It is the third largest city in the European Union, after London and Berlin, and its metropolitan...

and visited the line Orléans

Orléans

-Prehistory and Roman:Cenabum was a Gallic stronghold, one of the principal towns of the Carnutes tribe where the Druids held their annual assembly. It was conquered and destroyed by Julius Caesar in 52 BC, then rebuilt under the Roman Empire...

- Tours

Tours

Tours is a city in central France, the capital of the Indre-et-Loire department.It is located on the lower reaches of the river Loire, between Orléans and the Atlantic coast. Touraine, the region around Tours, is known for its wines, the alleged perfection of its local spoken French, and for the...

. On Prosper Enfantin's initiative, he and Talabot and Alois Negrelli

Alois Negrelli

Alois Negrelli, Ritter von Moldelbe , was an engineer and railroad pioneer in Austria, Italy and Switzerland.-Biography:...

became members of the Société d'Études du canal de Suez in 1846, where they studied the feasibility of the Suez canal

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal , also known by the nickname "The Highway to India", is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Opened in November 1869 after 10 years of construction work, it allows water transportation between Europe and Asia without navigation...

. In late 1850, he was called by the Swiss Federal Council

Swiss Federal Council

The Federal Council is the seven-member executive council which constitutes the federal government of Switzerland and serves as the Swiss collective head of state....

to advise on the future Swiss railway net and its financial implications. From 1851 to 1853, he built the railway from Alexandria

Alexandria

Alexandria is the second-largest city of Egypt, with a population of 4.1 million, extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the north central part of the country; it is also the largest city lying directly on the Mediterranean coast. It is Egypt's largest seaport, serving...

to Cairo

Cairo

Cairo , is the capital of Egypt and the largest city in the Arab world and Africa, and the 16th largest metropolitan area in the world. Nicknamed "The City of a Thousand Minarets" for its preponderance of Islamic architecture, Cairo has long been a centre of the region's political and cultural life...

, which was extended to Suez

Suez

Suez is a seaport city in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez , near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same boundaries as Suez governorate. It has three harbors, Adabya, Ain Sokhna and Port Tawfiq, and extensive port facilities...

in 1858.

Other aspects of his life

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

Member of Parliament

Member of Parliament

A Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

for Whitby

Whitby (UK Parliament constituency)

Whitby was a parliamentary constituency centred on the town of Whitby in North Yorkshire. It returned one Member of Parliament to the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, MP elected by the first past the post system.-History:...

from 1847 until his death. Within the Tory

Tory

Toryism is a traditionalist and conservative political philosophy which grew out of the Cavalier faction in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It is a prominent ideology in the politics of the United Kingdom, but also features in parts of The Commonwealth, particularly in Canada...

party, he sat on right-wing , at that time hostile to free trade , and Stephenson appeared anxious to avoid change in almost any form . He was a commissioner of the short-lived London Metropolitan Commission of Sewers

Metropolitan Commission of Sewers

The Metropolitan Commission of Sewers was one of London's first steps towards bringing its sewer and drainage infrastructure under the control of a single public body. It was a precursor of the Metropolitan Board of Works.-Formation:...

from 1848. He was President of the Institution of Civil Engineers

Institution of Civil Engineers

Founded on 2 January 1818, the Institution of Civil Engineers is an independent professional association, based in central London, representing civil engineering. Like its early membership, the majority of its current members are British engineers, but it also has members in more than 150...

, for two years from 1855.

Robert’s father George died in 1848 aged 67. Robert died on 12 October 1859 at his London home aged 55. Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, FRS , was a British civil engineer who built bridges and dockyards including the construction of the first major British railway, the Great Western Railway; a series of steamships, including the first propeller-driven transatlantic steamship; and numerous important bridges...

had died one month earlier on 15 September 1859. Robert was buried in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey

The Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster, popularly known as Westminster Abbey, is a large, mainly Gothic church, in the City of Westminster, London, United Kingdom, located just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is the traditional place of coronation and burial site for English,...

next to Thomas Telford

Thomas Telford

Thomas Telford FRS, FRSE was a Scottish civil engineer, architect and stonemason, and a noted road, bridge and canal builder.-Early career:...

. Queen Victoria gave special permission for the cortege to pass through Hyde Park and 3,000 tickets were sold to spectators. In his eulogy, he was called ‘the greatest engineer of the present century’. In his will he left nearly £400,000 .

Stephenson was well respected by his engineering peers and had a lifetime friendship with Joseph Locke

Joseph Locke

Joseph Locke was a notable English civil engineer of the 19th century, particularly associated with railway projects...

, a rival engineer during his career a fact reflected in Locke being a pallbearer at his funeral . Another such friendship was with Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, FRS , was a British civil engineer who built bridges and dockyards including the construction of the first major British railway, the Great Western Railway; a series of steamships, including the first propeller-driven transatlantic steamship; and numerous important bridges...

, who often helped Stephenson on various projects , as did Stephenson for Brunel. The two were however diametrically opposed on one issue: that of Brunel’s advocacy of atmospheric railway

Atmospheric railway

An atmospheric railway uses air pressure to provide power for propulsion. In one plan a pneumatic tube is laid between the rails, with a piston running in it suspended from the train through a sealable slot in the top of the tube. Alternatively, the whole tunnel may be the pneumatic tube with the...

s; trains without a locomotive, driven by a piston sliding inside an evacuated pipe mounted between the rails. The pipe was to be kept evacuated by stationary steam-driven pumps at intervals along the railway, and Stephenson was convinced that the idea could not work. After Brunel's proposal was piloted on a small scale and proved unworkable, Stephenson was proven right.

The Stephenson Railway Museum

Stephenson Railway Museum

The Stephenson Railway Museum is managed by Tyne and Wear Museums on behalf on North Tyneside Council, and is located at Middle Engine Lane in North Shields, England....

in North Shields

North Shields

North Shields is a town on the north bank of the River Tyne, in the metropolitan borough of North Tyneside, in North East England...

is named after George and Robert Stephenson.

He was god-father to Robert Baden-Powell, whose full name was Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, the first two in honour of his godfather, the third his mother's maiden name.

In fiction

Stephenson appears as a character in the animeAnime

is the Japanese abbreviated pronunciation of "animation". The definition sometimes changes depending on the context. In English-speaking countries, the term most commonly refers to Japanese animated cartoons....

film

Film

A film, also called a movie or motion picture, is a series of still or moving images. It is produced by recording photographic images with cameras, or by creating images using animation techniques or visual effects...

Steamboy

Steamboy

is a 2004 Japanese animated steampunk film, produced by Sunrise, and directed and co-written by Katsuhiro Otomo, his second major anime release, following Akira. The film was released in Japan on July 17, 2004. Steamboy is the most expensive full length Japanese animated movie made to date...

, in that world

Parallel universe (fiction)

A parallel universe or alternative reality is a hypothetical self-contained separate reality coexisting with one's own. A specific group of parallel universes is called a "multiverse", although this term can also be used to describe the possible parallel universes that constitute reality...

having apparently lived until 1866. In the English dub of the film his character also speaks with a rather posh stereotypical English accent and not the northern tones Stephenson used. (In fact, the first biography of Stephenson, by J. C. Jeaffreson, makes clear that Stephenson went to some trouble to lose "the diction, idiom or intonation of North-country dialect". See Jeaffreson, "The Life of Robert Stephenson, FRS," (1864) vol. 1, page 77.)

In popular culture

- Irish band "The RevsThe RevsThe Revs were an indie rock band from Kilcar, Donegal, Ireland. The group consists of three childhood friends: Rory Gallagher on bass guitar and vocals, John McIntyre and Michael O' Donnell...

" wrote a song referencing Robert Stephenson - 'Robert'. - British steampunkSteampunkSteampunk is a sub-genre of science fiction, fantasy, alternate history, and speculative fiction that came into prominence during the 1980s and early 1990s. Steampunk involves a setting where steam power is still widely used—usually Victorian era Britain or "Wild West"-era United...

band "The Men That Will Not Be Blamed For NothingThe Men That Will Not Be Blamed for NothingThe Men That Will Not be Blamed for Nothing are a steampunk band from London. Their name is a reference to the chalked graffiti discovered above a section of blood-stained apron thought to have been discarded by Jack the Ripper as he fled the scene of Catherine Eddowes' murder...

" wrote a song titled "Steph(v)enson" about various engineers with the surname Stephenson, or as a matter of spelling, Stevenson

Further reading

Addeyman, John & Haworth, Victoria (2005) Robert Stephenson: Railway Engineer, North East Railway Association, Amadeus Press ISBN 1-873513-60-7- Bailey, Michael R. (ed.) (2003) Robert Stephenson; The Eminent Engineer, Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, ISBN 0-7546-3679-8

- Dugan, Sally (2003) Men of Iron, London: Channel Four Books, ISBN 1-4050-3426-2

- Haworth, Victoria (2004) Robert Stephenson: The Making of a Prodigy, Newcastle-upon-Tyne: The Rocket Press, ISBN 0-9535-1621-0

- PR Lewis and C Gagg (2004), Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 45, 29.

- PR Lewis,(2008) Disaster on the Dee: Robert Stephenson's Nemesis of 1847, Tempus Publishing (2007) ISBN 978 0 7524 4266 2

- Robbins, Michael (1981) George and Robert Stephenson, London: Her majesty’s Stationery Office, ISBN 0-11-290342-8

- Rolt, L.T.C. (1960) George and Robert Stephenson: The Railway Revolution, London: Penguin, ISBN 0-14-007646-8

- Smith, Ken (2003) Stephenson Power: The Story of George and Robert Stephenson, Newcastle upon Tyne: Tyne Bridge Publishing, ISBN 1857951867