Second English Civil War

Encyclopedia

The Second English Civil War (1648–1649) was the second of three wars known as the English Civil War

(or Wars) which refers to the series of armed conflicts and political machinations which took place between Parliamentarians

and Royalist

s from 1642 until 1652 and also include the First English Civil War

(1642–1646) and the Third English Civil War

(1649–1651).

, in 1646, left a partial power vacuum in which any combination of the three English factions, Royalists, Independents

of the New Model Army

(henceforward called the Army), and Presbyterians of the English Parliament, as well as the Scottish Parliament allied with the Scottish Presbyterians (the Kirk

), could prove strong enough to dominate the rest. Armed political Royalism

was at an end, but despite being a prisoner, King Charles I

was considered by himself and his opponents (almost to the last) as necessary to ensure the success of whichever group could come to terms with him. Thus he passed successively into the hands of the Scots, the Parliament and the Army. The King attempted to reverse the verdict of arms by coquetting with each in turn. On 3 June 1647 Cornet George Joyce

of Thomas Fairfax's

horse seized the King for the Army, after which the English Presbyterians and the Scots, began to prepare for a fresh civil war, this time against Independency, as embodied in the Army. After making use of the Army's sword, its opponents attempted to disband it, to send it on foreign service and to cut off its arrears of pay. The result was that the Army leadership was exasperated beyond control, and, remembering not merely their grievances but also the principle for which the Army had fought, it soon became the most powerful political force in the realm. From 1646 to 1648 the breach between Army and Parliament widened day by day until finally the Presbyterian party, combined with the Scots and the remaining Royalists, felt itself strong enough to begin a Second Civil War.

, the Parliamentary Governor of Pembroke Castle

, refused to hand over his command to one of Fairfax's officers, and he was soon joined by some hundreds of officers and men, who mutinied, ostensibly for arrears of pay, but really with political objectives. At the end of March, encouraged by minor successes, Poyer openly declared for the King. Disbanded soldiers continued to join him in April, all South Wales

revolted, and eventually he was joined by Major-General Rowland Laugharne

, his district commander, and Colonel Rice Powell

. In April also news came that the Scots were arming and that Berwick

and Carlisle had been seized by the English Royalists.

Oliver Cromwell

was at once sent off at the head of a strong detachment to deal with Laugharne and Poyer. But before he arrived Laugharne had been severely defeated on the 8 May by Colonel Thomas Horton at the Battle of St. Fagans

. The English Presbyterians found it difficult to reconcile their principles with their allies when it appeared that the prisoners taken at St Fagans bore "We long to see our King" on their hats; very soon in fact the English war became almost purely a Royalist revolt, and the war in the north an attempt to enforce a mixture of Royalism and Presbyterianism

on Englishmen by means of a Scottish army. The former were disturbers of the peace and no more. Nearly all the Royalists who had fought in the First Civil War had given their parole not to bear arms against the Parliament, and many honourable Royalists, foremost amongst them the old Lord Astley

, who had fought the last battle for the King in 1646, refused to break their word by taking any part in the second war. Those who did so, and by implication those who abetted them in doing so, were likely to be treated with the utmost rigour if captured, for the Army was in a less placable mood in 1648 than in 1645, and had already determined to "call Charles Stuart, that man of blood

, to an account for the blood he had shed."

's town crier

had proclaimed the county committee's order for the suppression of Christmas Day and its treatment as any other working day. However, a large crowd gathered 3 days later to demand a church service, decorate doorways with holly bushes, and keep the shops shut. This crowd - under the slogan 'For God, King Charles, and Kent' - then descended into violence and riot, with a soldier being assaulted, the mayor's house attacked, and the city under the rioters' control for several weeks until forced to surrender in early January.

On 21 May 1648, Kent

rose in revolt in the King's name, and a few days later a most serious blow to the Independents was struck by the defection of the Navy, from command of which they had removed Vice-Admiral William Batten

, as being a Presbyterian. Though a former Lord High Admiral, the Earl of Warwick

, also a Presbyterian, was brought back to the service, it was not long before the Navy made a purely Royalist declaration and placed itself under the command of the Prince of Wales

. But Fairfax had a clearer view and a clearer purpose than the distracted Parliament. He moved quickly into Kent, and on the evening of 1 June, stormed Maidstone

by open force, after which the local levies dispersed to their homes, and the more determined Royalists, after a futile attempt to induce the City of London

to declare for them, fled into Essex

.

to deal with the remnants of the Kentish revolt in the east of the county, where the naval vessels in the Downs had gone over to the Royalists and Royalist forces had taken control of the three previously Parliamentarian "castles of the Downs" (Walmer

, Deal

, and Sandown

) and were trying to take control of Dover Castle

. Rich arrived at Dover on 5 June 1648 and prevented the attempt, before moving to the Downs

. It took almost a month to retake Walmer (15 June-12 July), before moving on to Deal and Sandown castles. Even then, due to the small size of Rich's force, he was unable to surround both Sandown and Deal at once and the two garrisons were able to send help to each other. At Deal he was also under bombardment from the Royalist warships, which had arrived on 15 July but been prevented from landing reinforcements. On 16th, thirty Flemish

ships arrived with about 1500 mercenaries

and - though the ships soon left when the Royalists ran out of money to pay them - this incited sufficient Kentish fear of foreign invasion to allow Sir Michael Livesey

to raise a large enough force to come to Colonel Rich's aid.

On 28 July, the Royalist warships returned and, after 3 weeks of failed attempts to land a relief force at Deal, on the night of 13 August, managed to land 800 soldiers and sailors under cover of darkness. This force might have been able to surprise the besieging Parliamentarian force from behind had it not been for a Royalist deserter who alerted the besiegers in time to defeat the Royalists, with less than a hundred of them managing to get back to the ships (though 300 managed to flee to Sandown Castle). Another attempt at landing soon afterwards also failed and, when on 23 August news was fired into Deal Castle on an arrow of Cromwell's victory at Preston

, most Royalist hope was lost and 2 days later Deal's garrison surrendered, followed by Sandown on 5 September. This finally ended the Kentish rebellion. Rich was made Captain of Deal Castle, a position he held until 1653 and in which he spent around £500 on repairs.

, Northamptonshire

, North Wales

, and Lincolnshire

the revolt collapsed as easily as that in Kent. Only in South Wales

, Essex

, and the north of England was there serious fighting. In the first of these districts, South Wales, Cromwell rapidly reduced all the fortresses except Pembroke. Here Laugharne, Poyer, and Powel held out with the desperate courage of deserters.

In the north, Pontefract Castle

In the north, Pontefract Castle

was surprised by the Royalists, and shortly afterwards Scarborough Castle

declared for the King as well. Fairfax, after his success at Maidstone and the pacification of Kent, turned northward to reduce Essex, where, under their ardent, experienced, and popular leader Sir Charles Lucas

, the Royalists were in arms in great numbers. Fairfax soon drove Lucas into Colchester

, but the first attack on the town was repulsed and he had to settle down to a long and wearisome siege

.

A Surrey

rising is remembered only for the death of the young and gallant Lord Francis Villiers

, younger brother of George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham

, in a skirmish at Kingston

(July 7, 1648). The rising collapsed almost as soon as it had gathered force, and its leaders, the Duke of Buckingham

and Henry Rich, the Earl of Holland

, escaped, after another attempt to induce London to declare for them, to St Albans

and St Neots

, where Holland was taken prisoner. Buckingham escaped overseas.

, a brilliant young Parliamentarian commander of twenty-nine, was more than equal to the situation. He left the sieges of Pontefract Castle

and Scarborough Castle

to Colonel Edward Rossiter

, and hurried into Cumberland to deal with the English Royalists under Sir Marmaduke Langdale

. With his cavalry, Lambert got into touch with the enemy about Carlisle and slowly fell back to Bowes

and Barnard Castle

. Lambert fought small rearguard actions to annoy the enemy and gain time. Langdale did not follow him into the mountains. Instead, he occupied himself in gathering recruits, supplies of material, and food for the advancing Scots.

Lambert, reinforced from the Midlands, reappeared early in June and drove Langdale back to Carlisle with his work half finished. About the same time, the local horse of Durham

and Northumberland

were put into the field for the Parliamentarians by Sir Arthur Hesilrige, governor of Newcastle

. On 30 June, under the direct command of Colonel Robert Lilburne

, these mounted forces won a considerable success at the River Coquet

.

This reverse, coupled with the existence of Langdale's Royalist force on the Cumberland side, practically compelled Hamilton

to choose the west coast route for his advance. His Scottish Engager army began slowly to move down the long couloir

between the mountains and the sea. The Campaign of Preston which followed is one of the most brilliant in English history.

in support of the English Royalist, the military situation was well defined. For the Parliamentarians, Cromwell besieged Pembroke

in South Wales, Fairfax besieged Colchester

in Essex, and Colonel Rossiter besieged Pontefract

and Scarborough in the north. On 11 July, Pembroke fell and Colchester followed on 28 August. Elsewhere the rebellion, which had been put down by rapidity of action rather than sheer weight of numbers, smouldered, and Charles, the Prince of Wales

, with the fleet cruised along the Essex coast. Cromwell and Lambert, however, understood each other perfectly, while the Scottish commanders quarrelled with each other and with Langdale.

As the English uprisings were close to collapse, it was on the adventures of the Engager Scottish army that the interest of the war centred. It was by no means the veteran army of the Earl of Leven

, which had long been disbanded. For the most part it consisted of raw levies and, as the Kirk party

had refused to sanction The Engagement (an agreement between Charles I and the Scots Parliament

for the Scots to intervene in England on behalf of Charles), David Leslie and thousands of experienced officers and men declined to serve. The leadership of James Hamilton, the Duke of Hamilton

proved to be a poor substitute for that of Leslie. Hamilton's army, too, was so ill provided that as soon as England was invaded it began to plunder the countryside for the bare means of sustenance.

On 8 July 1648, the Scots, with Langdale as advanced guard, were about Carlisle, and reinforcements from Ulster

were expected daily. Lambert's horse were at Penrith

, Hexham

and Newcastle, too weak to fight and having only skillful leading and rapidity of movement to enable them to gain time.

Appleby Castle

surrendered to the Scots on 31 July, whereat Lambert, who was still hanging on to the flank of the Scottish advance, fell back from Barnard Castle

to Richmond

so as to close Wensleydale

against any attempt of the invaders to march on Pontefract

. All the restless energy of Langdale's horse was unable to dislodge Lambert from the passes or to find out what was behind that impenetrable cavalry screen. The crisis was now at hand. Cromwell had received the surrender of Pembroke Castle on 11 July, and had marched off, with his men unpaid, ragged and shoeless, at full speed through the Midlands. Rains and storms delayed his march, but he knew that the Duke of Hamilton in the broken ground of Westmorland was still worse off. Shoes from Northampton

and stockings from Coventry

met him, at Nottingham

, and, gathering up the local levies as he went, he made for Doncaster

, where he arrived on 8 August, having gained six days in advance of the time he had allowed himself for the march. He then called up artillery from Hull

, exchanged his local levies for the regulars who were besieging Pontefract, and set off to meet Lambert. On 12 August he was at Wetherby

, Lambert with horse and foot at Otley

, Langdale at Skipton

and Gargrave

, Hamilton at Lancaster, and Sir George Monro

with the Scots from Ulster and the Carlisle Royalists (organized as a separate command owing to friction between Monro and the generals of the main army) at Hornby

. On 13 August, while Cromwell was marching to join Lambert at Otley, the Scottish leaders were still disputing whether they should make for Pontefract or continue through Lancashire

so as to join Lord Byron

and the Cheshire Royalists.

, and on 16 August they marched down the valley of the Ribble

towards Preston with full knowledge of the enemy's dispositions and full determination to attack him. They had with them horse and foot not only of the Army, but also of the militia of Yorkshire

, Durham, Northumberland and Lancashire, and withal were heavily outnumbered, having only 8,600 men against perhaps 20,000 of Hamilton's command. But the latter were scattered for convenience of supply along the road from Lancaster, through Preston, towards Wigan

, Langdale's corps having thus become the left flank guard instead of the advanced guard.

Langdale called in his advanced parties, perhaps with a view to resuming the duties of advanced guard, on the night of 13 August, and collected them near Longridge

. It is not clear whether he reported Cromwell's advance, but, if he did, Hamilton ignored the report, for on 17 August Monro was half a day's march to the north, Langdale east of Preston, and the main army strung out on the Wigan road, Major-General William Baillie with a body of foot, the rear of the column, being still in Preston. Hamilton, yielding to the importunity of his lieutenant-general, James Livingston, 1st Earl of Callendar

, sent Baillie across the Ribble to follow the main body just as Langdale, with 3,000 foot and 500 horse only, met the first shock of Cromwell's attack on Preston Moor. Hamilton, like Charles at Edgehill, passively shared in, without directing, the Battle of Preston

, and, though Langdale's men fought magnificently, they were after four hours' struggle driven to the Ribble.

Baillie attempted to cover the Ribble and Darwen

bridges on the Wigan road, but Cromwell had forced his way across both before nightfall. Pursuit was at once undertaken, and not relaxed until Hamilton had been driven through Wigan and Winwick

to Uttoxeter

and Ashbourne

. There, pressed furiously in rear by Cromwell's horse and held up in front by the militia of the midlands, the remnant of the Scottish army laid down its arms on 25 August. Various attempts were made to raise the Royalist standard in Wales and elsewhere, but Preston was the death-blow. On 28 August, starving and hopeless of relief, the Colchester Royalists surrendered to Lord Fairfax.

and Sir George Lisle

were shot. Laugharne, Poyer and Powel were sentenced to death, but Poyer alone was executed on 25 April 1649, being the victim selected by lot. Of five prominent Royalist peers who had fallen into the hands of Parliament, three, the Duke of Hamilton, the Earl of Holland, and Lord Capel, one of the Colchester prisoners and a man of high character, were beheaded at Westminster on 9 March. Above all, after long hesitations, even after renewal of negotiations, the Army and the Independents conducted "Pride's Purge

" of the House removing their ill-wishers, and created a court for the trial and sentence of King Charles I. At the end of the trial the 59 Commissioners (judges) found Charles I guilty of high treason

, as a "tyrant, traitor, murderer and public enemy". He was beheaded on a scaffold in front of the Banqueting House

of the Palace of Whitehall

on 30 January 1649. (After the Restoration

in 1660, the regicides who were still alive and not living in exile were either executed or sentenced to life imprisonment.)

was noted by Oliver Cromwell

as "[...] one of the strongest inland garrisons in the kingdom". Even in ruins, the castle held out in the north for the Royalists. Upon the execution of Charles I, the garrison recognised Charles II

as King and refused to surrender. It was the last Royalist stronghold to surrender. On 24 March 1649, almost two months after Charles was beheaded, the garrison finally capitulated. Parliament had the remains of the castle demolished the same year.

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

(or Wars) which refers to the series of armed conflicts and political machinations which took place between Parliamentarians

Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England. In 1066, William of Normandy introduced a feudal system, by which he sought the advice of a council of tenants-in-chief and ecclesiastics before making laws...

and Royalist

Cavalier

Cavalier was the name used by Parliamentarians for a Royalist supporter of King Charles I and son Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration...

s from 1642 until 1652 and also include the First English Civil War

First English Civil War

The First English Civil War began the series of three wars known as the English Civil War . "The English Civil War" was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations that took place between Parliamentarians and Royalists from 1642 until 1651, and includes the Second English Civil War and...

(1642–1646) and the Third English Civil War

Third English Civil War

The Third English Civil War was the last of the English Civil Wars , a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists....

(1649–1651).

Overview

The end of the First Civil WarFirst English Civil War

The First English Civil War began the series of three wars known as the English Civil War . "The English Civil War" was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations that took place between Parliamentarians and Royalists from 1642 until 1651, and includes the Second English Civil War and...

, in 1646, left a partial power vacuum in which any combination of the three English factions, Royalists, Independents

Good Old Cause

The Good Old Cause was the retrospective name given by the soldiers of the New Model Army for the complex of reasons for which they fought, on behalf of the Parliament of England....

of the New Model Army

New Model Army

The New Model Army of England was formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians in the English Civil War, and was disbanded in 1660 after the Restoration...

(henceforward called the Army), and Presbyterians of the English Parliament, as well as the Scottish Parliament allied with the Scottish Presbyterians (the Kirk

Kirk

Kirk can mean "church" in general or the Church of Scotland in particular. Many place names and personal names are also derived from it.-Basic meaning and etymology:...

), could prove strong enough to dominate the rest. Armed political Royalism

Cavalier

Cavalier was the name used by Parliamentarians for a Royalist supporter of King Charles I and son Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration...

was at an end, but despite being a prisoner, King Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

was considered by himself and his opponents (almost to the last) as necessary to ensure the success of whichever group could come to terms with him. Thus he passed successively into the hands of the Scots, the Parliament and the Army. The King attempted to reverse the verdict of arms by coquetting with each in turn. On 3 June 1647 Cornet George Joyce

George Joyce

Cornet George Joyce was an officer in the Parliamentary New Model Army during the English Civil War.Between 2 June and June 5 1647, while the New Model Army was assembling for rendezvous at the behest of the recently formed Army Council, George Joyce seized King Charles I from Parliament's custody...

of Thomas Fairfax's

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron was a general and parliamentary commander-in-chief during the English Civil War...

horse seized the King for the Army, after which the English Presbyterians and the Scots, began to prepare for a fresh civil war, this time against Independency, as embodied in the Army. After making use of the Army's sword, its opponents attempted to disband it, to send it on foreign service and to cut off its arrears of pay. The result was that the Army leadership was exasperated beyond control, and, remembering not merely their grievances but also the principle for which the Army had fought, it soon became the most powerful political force in the realm. From 1646 to 1648 the breach between Army and Parliament widened day by day until finally the Presbyterian party, combined with the Scots and the remaining Royalists, felt itself strong enough to begin a Second Civil War.

Revolt against Parliament in South Wales

In February 1648 Colonel John PoyerJohn Poyer

John Poyer was a soldier in the Parliamentary army during the English Civil War in South Wales. He later rebelled and was executed for treason.- Background :...

, the Parliamentary Governor of Pembroke Castle

Pembroke Castle

Pembroke Castle is a medieval castle in Pembroke, West Wales. Standing beside the River Cleddau, it underwent major restoration work in the early 20th century. The castle was the original seat of the Earldom of Pembroke....

, refused to hand over his command to one of Fairfax's officers, and he was soon joined by some hundreds of officers and men, who mutinied, ostensibly for arrears of pay, but really with political objectives. At the end of March, encouraged by minor successes, Poyer openly declared for the King. Disbanded soldiers continued to join him in April, all South Wales

South Wales

South Wales is an area of Wales bordered by England and the Bristol Channel to the east and south, and Mid Wales and West Wales to the north and west. The most densely populated region in the south-west of the United Kingdom, it is home to around 2.1 million people and includes the capital city of...

revolted, and eventually he was joined by Major-General Rowland Laugharne

Rowland Laugharne

Major General Rowland Laugharne was a soldier in the English Civil War.His family came from St. Brides House, Pembrokeshire, Wales.Major-General Laugharne, Parliament's commander in south Wales during the First Civil War, sided with the insurgents and took command of the rebel army...

, his district commander, and Colonel Rice Powell

Rice Powell

Rice Powell was a Colonel in the Parliamentary army during the First English Civil War. In the Second English Civil War he allied himself with the Royalist cause. English Civil Wars. He fought in South Wales and played a significant part in events between 1642 and 1649 including a senior role...

. In April also news came that the Scots were arming and that Berwick

Berwick-upon-Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed or simply Berwick is a town in the county of Northumberland and is the northernmost town in England, on the east coast at the mouth of the River Tweed. It is situated 2.5 miles south of the Scottish border....

and Carlisle had been seized by the English Royalists.

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

was at once sent off at the head of a strong detachment to deal with Laugharne and Poyer. But before he arrived Laugharne had been severely defeated on the 8 May by Colonel Thomas Horton at the Battle of St. Fagans

Battle of St. Fagans

The Battle of St. Fagans was a pitched battle in the Second English Civil War in 1648. A detachment from the New Model Army defeated an army of former Parliamentarian soldiers who had rebelled and were now fighting against Parliament.-Background:...

. The English Presbyterians found it difficult to reconcile their principles with their allies when it appeared that the prisoners taken at St Fagans bore "We long to see our King" on their hats; very soon in fact the English war became almost purely a Royalist revolt, and the war in the north an attempt to enforce a mixture of Royalism and Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism refers to a number of Christian churches adhering to the Calvinist theological tradition within Protestantism, which are organized according to a characteristic Presbyterian polity. Presbyterian theology typically emphasizes the sovereignty of God, the authority of the Scriptures,...

on Englishmen by means of a Scottish army. The former were disturbers of the peace and no more. Nearly all the Royalists who had fought in the First Civil War had given their parole not to bear arms against the Parliament, and many honourable Royalists, foremost amongst them the old Lord Astley

Jacob Astley, 1st Baron Astley of Reading

Jacob Astley, 1st Baron Astley of Reading was a Royalist commander in the English Civil War.-Life:He came from an established Norfolk family, and was born at Melton Constable. His first experiences of war were at the age of 18 when he joined the Islands Voyage expedition in 1597 under the Earl of...

, who had fought the last battle for the King in 1646, refused to break their word by taking any part in the second war. Those who did so, and by implication those who abetted them in doing so, were likely to be treated with the utmost rigour if captured, for the Army was in a less placable mood in 1648 than in 1645, and had already determined to "call Charles Stuart, that man of blood

Charles Stuart, that man of blood

Charles Stuart, that man of blood was a phrase used by Independents, during the English Civil War to describe King Charles IThe phrase is derived from the Bible:and other verses were used to justify regicide:-Windsor Castle prayer meeting:...

, to an account for the blood he had shed."

Revolt against Parliament in Kent

A precursor to Kent's Second Civil War had come on Wednesday, 22 December 1647, when CanterburyCanterbury

Canterbury is a historic English cathedral city, which lies at the heart of the City of Canterbury, a district of Kent in South East England. It lies on the River Stour....

's town crier

Town crier

A town crier, or bellman, is an officer of the court who makes public pronouncements as required by the court . The crier can also be used to make public announcements in the streets...

had proclaimed the county committee's order for the suppression of Christmas Day and its treatment as any other working day. However, a large crowd gathered 3 days later to demand a church service, decorate doorways with holly bushes, and keep the shops shut. This crowd - under the slogan 'For God, King Charles, and Kent' - then descended into violence and riot, with a soldier being assaulted, the mayor's house attacked, and the city under the rioters' control for several weeks until forced to surrender in early January.

On 21 May 1648, Kent

Kent

Kent is a county in southeast England, and is one of the home counties. It borders East Sussex, Surrey and Greater London and has a defined boundary with Essex in the middle of the Thames Estuary. The ceremonial county boundaries of Kent include the shire county of Kent and the unitary borough of...

rose in revolt in the King's name, and a few days later a most serious blow to the Independents was struck by the defection of the Navy, from command of which they had removed Vice-Admiral William Batten

William Batten

Sir William Batten was an English naval officer and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1661 to 1667.Batten was the son of Andrew Batten, master in the Royal Navy. In 1625 he was stated to be one of the commanders of two ships sent on a whaling voyage to Spitsbergen by the Yarmouth...

, as being a Presbyterian. Though a former Lord High Admiral, the Earl of Warwick

Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick

Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick was an English colonial administrator, admiral, and puritan.Rich was the eldest son of Robert Rich, 1st Earl of Warwick and his wife Penelope Devereux, Lady Rich, and succeeded to his father's title in 1619...

, also a Presbyterian, was brought back to the service, it was not long before the Navy made a purely Royalist declaration and placed itself under the command of the Prince of Wales

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

. But Fairfax had a clearer view and a clearer purpose than the distracted Parliament. He moved quickly into Kent, and on the evening of 1 June, stormed Maidstone

Battle of Maidstone

The Battle of Maidstone was fought in the Second English Civil War and was a victory for the attacking parliamentarian troops over the defending Royalist forces.- Background :...

by open force, after which the local levies dispersed to their homes, and the more determined Royalists, after a futile attempt to induce the City of London

City of London

The City of London is a small area within Greater London, England. It is the historic core of London around which the modern conurbation grew and has held city status since time immemorial. The City’s boundaries have remained almost unchanged since the Middle Ages, and it is now only a tiny part of...

to declare for them, fled into Essex

Essex

Essex is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East region of England, and one of the home counties. It is located to the northeast of Greater London. It borders with Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent to the South and London to the south west...

.

The Downs

Before leaving for Essex, Fairfax delegated command of the Parliamentarian forces to Colonel Nathaniel RichNathaniel Rich (soldier)

Colonel Nathaniel Rich sided with Parliament in the English Civil War. He was a colonel in Oliver Cromwell's New Model Army.-Life:...

to deal with the remnants of the Kentish revolt in the east of the county, where the naval vessels in the Downs had gone over to the Royalists and Royalist forces had taken control of the three previously Parliamentarian "castles of the Downs" (Walmer

Walmer Castle

Walmer Castle was built by Henry VIII in 1539–1540 as an artillery fortress to counter the threat of invasion from Catholic France and Spain. It was part of his programme to create a chain of coastal defences along England's coast known as the Device Forts or as Henrician Castles...

, Deal

Deal Castle

Deal Castle is located in Deal, Kent, England, between Walmer Castle and the now lost Sandown Castle .-Construction:It is one of the most impressive of the Device Forts or Henrician Castles built by Henry VIII between 1539 and 1540 as an artillery fortress to counter the threat of invasion from...

, and Sandown

Sandown Castle, Kent

Sandown Castle was one of Henry VIII's Device Forts or Henrician Castles built at Sandown, North Deal, Kent as part of Henry VIII's chain of coastal fortifications to defend England against the threat of foreign invasion. It made up a line of defences with Walmer Castle and Deal Castle to protect...

) and were trying to take control of Dover Castle

Dover Castle

Dover Castle is a medieval castle in the town of the same name in the English county of Kent. It was founded in the 12th century and has been described as the "Key to England" due to its defensive significance throughout history...

. Rich arrived at Dover on 5 June 1648 and prevented the attempt, before moving to the Downs

The Downs

The Downs are a roadstead or area of sea in the southern North Sea near the English Channel off the east Kent coast, between the North and the South Foreland in southern England. In 1639 the Battle of the Downs took place here, when the Dutch navy destroyed a Spanish fleet which had sought refuge...

. It took almost a month to retake Walmer (15 June-12 July), before moving on to Deal and Sandown castles. Even then, due to the small size of Rich's force, he was unable to surround both Sandown and Deal at once and the two garrisons were able to send help to each other. At Deal he was also under bombardment from the Royalist warships, which had arrived on 15 July but been prevented from landing reinforcements. On 16th, thirty Flemish

Flanders

Flanders is the community of the Flemings but also one of the institutions in Belgium, and a geographical region located in parts of present-day Belgium, France and the Netherlands. "Flanders" can also refer to the northern part of Belgium that contains Brussels, Bruges, Ghent and Antwerp...

ships arrived with about 1500 mercenaries

Mercenary

A mercenary, is a person who takes part in an armed conflict based on the promise of material compensation rather than having a direct interest in, or a legal obligation to, the conflict itself. A non-conscript professional member of a regular army is not considered to be a mercenary although he...

and - though the ships soon left when the Royalists ran out of money to pay them - this incited sufficient Kentish fear of foreign invasion to allow Sir Michael Livesey

Michael Livesey

Sir Michael Livesey, 1st Baronet was one of the regicides of King Charles I.A Kentish baronet of Eastchurch on the Isle of Sheppey, Livesey was a zealous Puritan who sided with Parliament during the civil wars. He became active on the Kent county committee and was appointed Sheriff of Kent in 1643...

to raise a large enough force to come to Colonel Rich's aid.

On 28 July, the Royalist warships returned and, after 3 weeks of failed attempts to land a relief force at Deal, on the night of 13 August, managed to land 800 soldiers and sailors under cover of darkness. This force might have been able to surprise the besieging Parliamentarian force from behind had it not been for a Royalist deserter who alerted the besiegers in time to defeat the Royalists, with less than a hundred of them managing to get back to the ships (though 300 managed to flee to Sandown Castle). Another attempt at landing soon afterwards also failed and, when on 23 August news was fired into Deal Castle on an arrow of Cromwell's victory at Preston

Battle of Preston (1648)

The Battle of Preston , fought largely at Walton-le-Dale near Preston in Lancashire, resulted in a victory by the troops of Oliver Cromwell over the Royalists and Scots commanded by the Duke of Hamilton...

, most Royalist hope was lost and 2 days later Deal's garrison surrendered, followed by Sandown on 5 September. This finally ended the Kentish rebellion. Rich was made Captain of Deal Castle, a position he held until 1653 and in which he spent around £500 on repairs.

Revolt elsewhere

In CornwallCornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

, Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire is a landlocked county in the English East Midlands, with a population of 629,676 as at the 2001 census. It has boundaries with the ceremonial counties of Warwickshire to the west, Leicestershire and Rutland to the north, Cambridgeshire to the east, Bedfordshire to the south-east,...

, North Wales

North Wales

North Wales is the northernmost unofficial region of Wales. It is bordered to the south by the counties of Ceredigion and Powys in Mid Wales and to the east by the counties of Shropshire in the West Midlands and Cheshire in North West England...

, and Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire is a county in the east of England. It borders Norfolk to the south east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south west, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire to the west, South Yorkshire to the north west, and the East Riding of Yorkshire to the north. It also borders...

the revolt collapsed as easily as that in Kent. Only in South Wales

South Wales

South Wales is an area of Wales bordered by England and the Bristol Channel to the east and south, and Mid Wales and West Wales to the north and west. The most densely populated region in the south-west of the United Kingdom, it is home to around 2.1 million people and includes the capital city of...

, Essex

Essex

Essex is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East region of England, and one of the home counties. It is located to the northeast of Greater London. It borders with Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent to the South and London to the south west...

, and the north of England was there serious fighting. In the first of these districts, South Wales, Cromwell rapidly reduced all the fortresses except Pembroke. Here Laugharne, Poyer, and Powel held out with the desperate courage of deserters.

Pontefract Castle

Pontefract Castle is a castle in the town of Pontefract, in the City of Wakefield, West Yorkshire, England. It was the site of the demise of Richard II of England, and later the place of a series of famous sieges during the English Civil War-History:...

was surprised by the Royalists, and shortly afterwards Scarborough Castle

Scarborough Castle

Scarborough Castle is a former medieval Royal fortress situated on a rocky promontory overlooking the North Sea and Scarborough, North Yorkshire, England...

declared for the King as well. Fairfax, after his success at Maidstone and the pacification of Kent, turned northward to reduce Essex, where, under their ardent, experienced, and popular leader Sir Charles Lucas

Charles Lucas

Sir Charles Lucas was an English soldier, a Royalist commander in the English Civil War.-Biography:Lucas was the son of Sir Thomas Lucas of Colchester, Essex. As a young man Lucas served in the Netherlands under the command of his brother, and in the "Bishops' Wars" he commanded Cheesea troop of...

, the Royalists were in arms in great numbers. Fairfax soon drove Lucas into Colchester

Colchester

Colchester is an historic town and the largest settlement within the borough of Colchester in Essex, England.At the time of the census in 2001, it had a population of 104,390. However, the population is rapidly increasing, and has been named as one of Britain's fastest growing towns. As the...

, but the first attack on the town was repulsed and he had to settle down to a long and wearisome siege

Siege of Colchester

The siege of Colchester occurred in the summer of 1648 when the English Civil War reignited in several areas of Britain. Colchester found itself in the thick of the unrest when a Royalist army on its way through East Anglia to raise support for the King, was attacked by Lord-General Thomas Fairfax...

.

A Surrey

Surrey

Surrey is a county in the South East of England and is one of the Home Counties. The county borders Greater London, Kent, East Sussex, West Sussex, Hampshire and Berkshire. The historic county town is Guildford. Surrey County Council sits at Kingston upon Thames, although this has been part of...

rising is remembered only for the death of the young and gallant Lord Francis Villiers

George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham

George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, 20th Baron de Ros of Helmsley, KG, PC, FRS was an English statesman and poet.- Upbringing and education :...

, younger brother of George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham

George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham

George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, 20th Baron de Ros of Helmsley, KG, PC, FRS was an English statesman and poet.- Upbringing and education :...

, in a skirmish at Kingston

Kingston upon Thames

Kingston upon Thames is the principal settlement of the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames in southwest London. It was the ancient market town where Saxon kings were crowned and is now a suburb situated south west of Charing Cross. It is one of the major metropolitan centres identified in the...

(July 7, 1648). The rising collapsed almost as soon as it had gathered force, and its leaders, the Duke of Buckingham

George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham

George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, 20th Baron de Ros of Helmsley, KG, PC, FRS was an English statesman and poet.- Upbringing and education :...

and Henry Rich, the Earl of Holland

Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland

Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland was an English aristocrat, courtier and soldier.-Life:He was the son of Robert Rich, 1st Earl of Warwick and of Penelope Devereux, Lady Rich, and the younger brother of Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick...

, escaped, after another attempt to induce London to declare for them, to St Albans

St Albans

St Albans is a city in southern Hertfordshire, England, around north of central London, which forms the main urban area of the City and District of St Albans. It is a historic market town, and is now a sought-after dormitory town within the London commuter belt...

and St Neots

St Neots

St Neots is a town and civil parish with a population of 26,356 people. It lies on the River Great Ouse in Huntingdonshire District, approximately north of central London, and is the largest town in Cambridgeshire . The town is named after the Cornish monk St...

, where Holland was taken prisoner. Buckingham escaped overseas.

Lambert in the north

Major-General John LambertJohn Lambert (general)

John Lambert was an English Parliamentary general and politician. He fought during the English Civil War and then in Oliver Cromwell's Scottish campaign , becoming thereafter active in civilian politics until his dismissal by Cromwell in 1657...

, a brilliant young Parliamentarian commander of twenty-nine, was more than equal to the situation. He left the sieges of Pontefract Castle

Pontefract Castle

Pontefract Castle is a castle in the town of Pontefract, in the City of Wakefield, West Yorkshire, England. It was the site of the demise of Richard II of England, and later the place of a series of famous sieges during the English Civil War-History:...

and Scarborough Castle

Scarborough Castle

Scarborough Castle is a former medieval Royal fortress situated on a rocky promontory overlooking the North Sea and Scarborough, North Yorkshire, England...

to Colonel Edward Rossiter

Edward Rossiter

Colonel Sir Edward Rossiter of Somerby by Bigby, Lincolnshire, England, was a soldier in the Parliamentarian army. He fought alongside Oliver Cromwell at the Battle of Naseby in 1645...

, and hurried into Cumberland to deal with the English Royalists under Sir Marmaduke Langdale

Marmaduke Langdale

Sir Marmaduke Langdale was a Royalist commander in the English Civil War.He married Lenox , daughter of Sir John Rodes of Barlborough, Derbyshire, and his third wife Catherine, daughter of Marmaduke Constable of Holderness on 12 September 1626, at St Michael-le-Belfry in York...

. With his cavalry, Lambert got into touch with the enemy about Carlisle and slowly fell back to Bowes

Bowes

Bowes is a village in County Durham, England. Located in the Pennine hills, it is situated close to Barnard Castle. It is built around the medieval Bowes Castle.-Civic history:...

and Barnard Castle

Barnard Castle

Barnard Castle is an historical town in Teesdale, County Durham, England. It is named after the castle around which it grew up. It sits on the north side of the River Tees, opposite Startforth, south southwest of Newcastle upon Tyne, south southwest of Sunderland, west of Middlesbrough and ...

. Lambert fought small rearguard actions to annoy the enemy and gain time. Langdale did not follow him into the mountains. Instead, he occupied himself in gathering recruits, supplies of material, and food for the advancing Scots.

Lambert, reinforced from the Midlands, reappeared early in June and drove Langdale back to Carlisle with his work half finished. About the same time, the local horse of Durham

Durham

Durham is a city in north east England. It is within the County Durham local government district, and is the county town of the larger ceremonial county...

and Northumberland

Northumberland

Northumberland is the northernmost ceremonial county and a unitary district in North East England. For Eurostat purposes Northumberland is a NUTS 3 region and is one of three boroughs or unitary districts that comprise the "Northumberland and Tyne and Wear" NUTS 2 region...

were put into the field for the Parliamentarians by Sir Arthur Hesilrige, governor of Newcastle

Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne is a city and metropolitan borough of Tyne and Wear, in North East England. Historically a part of Northumberland, it is situated on the north bank of the River Tyne...

. On 30 June, under the direct command of Colonel Robert Lilburne

Robert Lilburne

thumb|right|Robert LilburneColonel Robert Lilburne was the older brother of John Lilburne, the well known Leveller, but unlike his brother who severed his relationship with Oliver Cromwell, Robert Lilburne remained in the army...

, these mounted forces won a considerable success at the River Coquet

River Coquet

The River Coquet runs through the county of Northumberland, England, discharging into the North Sea on the east coast of England at Amble. Warkworth Castle is built in a loop of the Coquet....

.

This reverse, coupled with the existence of Langdale's Royalist force on the Cumberland side, practically compelled Hamilton

James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Hamilton

General Sir James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Hamilton KG was a Scottish nobleman and influential Civil war military leader.-Young Arran:...

to choose the west coast route for his advance. His Scottish Engager army began slowly to move down the long couloir

Couloir

A couloir is a narrow gully with a steep gradient in a mountainous terrain. A couloir may be a seam, scar, or fissure, or vertical crevasse in an otherwise solid mountain mass...

between the mountains and the sea. The Campaign of Preston which followed is one of the most brilliant in English history.

Campaign of Preston

On the 8 July 1648, when the Scottish Engager army crossed the BorderAnglo–Scottish border

The Anglo-Scottish border is the official border and mark of entry between Scotland and England. It runs for 154 km between the River Tweed on the east coast and the Solway Firth in the west. It is Scotland's only land border...

in support of the English Royalist, the military situation was well defined. For the Parliamentarians, Cromwell besieged Pembroke

Siege of Pembroke

The Siege of Pembroke took place in 1648 during the Second English Civil War.- Background :In April 1648, Parliamentarian troops in Wales, who had not been paid for a long time, staged a Royalist rebellion under the command of the Colonel John Poyer, the Parliamentarian Governor of Pembroke Castle...

in South Wales, Fairfax besieged Colchester

Siege of Colchester

The siege of Colchester occurred in the summer of 1648 when the English Civil War reignited in several areas of Britain. Colchester found itself in the thick of the unrest when a Royalist army on its way through East Anglia to raise support for the King, was attacked by Lord-General Thomas Fairfax...

in Essex, and Colonel Rossiter besieged Pontefract

Pontefract

Pontefract is an historic market town in West Yorkshire, England. Traditionally in the West Riding, near the A1 , the M62 motorway and Castleford. It is one of the five towns in the metropolitan borough of the City of Wakefield and has a population of 28,250...

and Scarborough in the north. On 11 July, Pembroke fell and Colchester followed on 28 August. Elsewhere the rebellion, which had been put down by rapidity of action rather than sheer weight of numbers, smouldered, and Charles, the Prince of Wales

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

, with the fleet cruised along the Essex coast. Cromwell and Lambert, however, understood each other perfectly, while the Scottish commanders quarrelled with each other and with Langdale.

As the English uprisings were close to collapse, it was on the adventures of the Engager Scottish army that the interest of the war centred. It was by no means the veteran army of the Earl of Leven

Alexander Leslie, 1st Earl of Leven

Alexander Leslie, 1st Earl of Leven was a Scottish soldier in Dutch, Swedish and Scottish service. Born illegitimate and raised as a foster child, he subsequently advanced to the rank of a Dutch captain, a Swedish Field Marshal, and in Scotland became lord general in command of the Covenanters,...

, which had long been disbanded. For the most part it consisted of raw levies and, as the Kirk party

Kirk Party

The Kirk Party were a radical Presbyterian faction of the Scottish Covenanters during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They came to the fore after the defeat of the Engagers faction in 1648 at the hands of Oliver Cromwell and the English Parliament...

had refused to sanction The Engagement (an agreement between Charles I and the Scots Parliament

Parliament of Scotland

The Parliament of Scotland, officially the Estates of Parliament, was the legislature of the Kingdom of Scotland. The unicameral parliament of Scotland is first found on record during the early 13th century, with the first meeting for which a primary source survives at...

for the Scots to intervene in England on behalf of Charles), David Leslie and thousands of experienced officers and men declined to serve. The leadership of James Hamilton, the Duke of Hamilton

James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Hamilton

General Sir James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Hamilton KG was a Scottish nobleman and influential Civil war military leader.-Young Arran:...

proved to be a poor substitute for that of Leslie. Hamilton's army, too, was so ill provided that as soon as England was invaded it began to plunder the countryside for the bare means of sustenance.

On 8 July 1648, the Scots, with Langdale as advanced guard, were about Carlisle, and reinforcements from Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

were expected daily. Lambert's horse were at Penrith

Penrith, Cumbria

Penrith was an urban district between 1894 and 1974, when it was merged into Eden District.The authority's area was coterminous with the civil parish of Penrith although when the council was abolished Penrith became an unparished area....

, Hexham

Hexham

Hexham is a market town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, located south of the River Tyne, and was the administrative centre for the Tynedale district from 1974 to 2009. The three major towns in Tynedale were Hexham, Prudhoe and Haltwhistle, although in terms of population, Prudhoe was...

and Newcastle, too weak to fight and having only skillful leading and rapidity of movement to enable them to gain time.

Appleby Castle

Appleby-in-Westmorland

Appleby-in-Westmorland is a town and civil parish in Cumbria, in North West England. It is situated within a loop of the River Eden and has a population of approximately 2,500. It is in the historic county of Westmorland, of which it was the county town. The town's name was simply Appleby, until...

surrendered to the Scots on 31 July, whereat Lambert, who was still hanging on to the flank of the Scottish advance, fell back from Barnard Castle

Barnard Castle

Barnard Castle is an historical town in Teesdale, County Durham, England. It is named after the castle around which it grew up. It sits on the north side of the River Tees, opposite Startforth, south southwest of Newcastle upon Tyne, south southwest of Sunderland, west of Middlesbrough and ...

to Richmond

Richmond, North Yorkshire

Richmond is a market town and civil parish on the River Swale in North Yorkshire, England and is the administrative centre of the district of Richmondshire. It is situated on the edge of the Yorkshire Dales National Park, and serves as the Park's main tourist centre...

so as to close Wensleydale

Wensleydale

Wensleydale is the valley of the River Ure on the east side of the Pennines in North Yorkshire, England.Wensleydale lies in the Yorkshire Dales National Park – one of only a few valleys in the Dales not currently named after its principal river , but the older name, "Yoredale", can still be seen...

against any attempt of the invaders to march on Pontefract

Pontefract

Pontefract is an historic market town in West Yorkshire, England. Traditionally in the West Riding, near the A1 , the M62 motorway and Castleford. It is one of the five towns in the metropolitan borough of the City of Wakefield and has a population of 28,250...

. All the restless energy of Langdale's horse was unable to dislodge Lambert from the passes or to find out what was behind that impenetrable cavalry screen. The crisis was now at hand. Cromwell had received the surrender of Pembroke Castle on 11 July, and had marched off, with his men unpaid, ragged and shoeless, at full speed through the Midlands. Rains and storms delayed his march, but he knew that the Duke of Hamilton in the broken ground of Westmorland was still worse off. Shoes from Northampton

Northampton

Northampton is a large market town and local government district in the East Midlands region of England. Situated about north-west of London and around south-east of Birmingham, Northampton lies on the River Nene and is the county town of Northamptonshire. The demonym of Northampton is...

and stockings from Coventry

Coventry

Coventry is a city and metropolitan borough in the county of West Midlands in England. Coventry is the 9th largest city in England and the 11th largest in the United Kingdom. It is also the second largest city in the English Midlands, after Birmingham, with a population of 300,848, although...

met him, at Nottingham

Nottingham

Nottingham is a city and unitary authority in the East Midlands of England. It is located in the ceremonial county of Nottinghamshire and represents one of eight members of the English Core Cities Group...

, and, gathering up the local levies as he went, he made for Doncaster

Doncaster

Doncaster is a town in South Yorkshire, England, and the principal settlement of the Metropolitan Borough of Doncaster. The town is about from Sheffield and is popularly referred to as "Donny"...

, where he arrived on 8 August, having gained six days in advance of the time he had allowed himself for the march. He then called up artillery from Hull

Kingston upon Hull

Kingston upon Hull , usually referred to as Hull, is a city and unitary authority area in the ceremonial county of the East Riding of Yorkshire, England. It stands on the River Hull at its junction with the Humber estuary, 25 miles inland from the North Sea. Hull has a resident population of...

, exchanged his local levies for the regulars who were besieging Pontefract, and set off to meet Lambert. On 12 August he was at Wetherby

Wetherby

Wetherby is a market town and civil parish within the metropolitan borough of the City of Leeds, in West Yorkshire, England. It stands on the River Wharfe, and has been for centuries a crossing place and staging post on the Great North Road, being mid-way between London and Edinburgh...

, Lambert with horse and foot at Otley

Otley

-Transport:The main roads through the town are the A660 to the south east, which connects Otley to Bramhope, Adel and Leeds city centre, and the A65 to the west, which goes to Ilkley and Skipton. The A6038 heads to Guiseley, Shipley and Bradford, connecting with the A65...

, Langdale at Skipton

Skipton

Skipton is a market town and civil parish within the Craven district of North Yorkshire, England. It is located along the course of both the Leeds and Liverpool Canal and the River Aire, on the south side of the Yorkshire Dales, northwest of Bradford and west of York...

and Gargrave

Gargrave

Gargrave is a small village and civil parish in the Craven district located along the A65, northwest of Skipton in North Yorkshire, England.It is situated on the very edge of the Yorkshire Dales. The River Aire and the Leeds and Liverpool Canal pass through the village...

, Hamilton at Lancaster, and Sir George Monro

George Munro, 1st of Newmore

Sir George Munro, 1st of Newmore was a 17th century Scottish soldier and member of parliament from the Clan Munro, Ross-shire, Scotland. He was seated at Newmore Castle.-Lineage:...

with the Scots from Ulster and the Carlisle Royalists (organized as a separate command owing to friction between Monro and the generals of the main army) at Hornby

Hornby

- Australia :* Hornby Lighthouse, third oldest lighthouse in Australia on south head of Sydney Harbour,- Canada :* Hornby, Ontario, community in Halton Hills* Hornby Island, Canadian island in the Strait of Georgia near Vancouver Island- England :...

. On 13 August, while Cromwell was marching to join Lambert at Otley, the Scottish leaders were still disputing whether they should make for Pontefract or continue through Lancashire

Lancashire

Lancashire is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in the North West of England. It takes its name from the city of Lancaster, and is sometimes known as the County of Lancaster. Although Lancaster is still considered to be the county town, Lancashire County Council is based in Preston...

so as to join Lord Byron

John Byron, 1st Baron Byron

John Byron, 1st Baron Byron was an English Royalist and supporter of Charles I during the English Civil War.-Life:...

and the Cheshire Royalists.

Battle of Preston

On 14 August 1648 Cromwell and Lambert were at Skipton, on 15 August at GisburnGisburn

Gisburn is a village, civil parish and ward within the Ribble Valley borough of Lancashire, England. It lies northeast of Clitheroe. The parish of Gisburn had a population of 506, and the ward had 1287, recorded in the 2001 census....

, and on 16 August they marched down the valley of the Ribble

River Ribble

The River Ribble is a river that runs through North Yorkshire and Lancashire, in northern England. The river's drainage basin also includes parts of Greater Manchester around Wigan.-Geography:...

towards Preston with full knowledge of the enemy's dispositions and full determination to attack him. They had with them horse and foot not only of the Army, but also of the militia of Yorkshire

Yorkshire

Yorkshire is a historic county of northern England and the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its great size in comparison to other English counties, functions have been increasingly undertaken over time by its subdivisions, which have also been subject to periodic reform...

, Durham, Northumberland and Lancashire, and withal were heavily outnumbered, having only 8,600 men against perhaps 20,000 of Hamilton's command. But the latter were scattered for convenience of supply along the road from Lancaster, through Preston, towards Wigan

Wigan

Wigan is a town in Greater Manchester, England. It stands on the River Douglas, south-west of Bolton, north of Warrington and west-northwest of Manchester. Wigan is the largest settlement in the Metropolitan Borough of Wigan and is its administrative centre. The town of Wigan had a total...

, Langdale's corps having thus become the left flank guard instead of the advanced guard.

Langdale called in his advanced parties, perhaps with a view to resuming the duties of advanced guard, on the night of 13 August, and collected them near Longridge

Longridge

Longridge is a small town and civil parish in the borough of Ribble Valley in Lancashire, England. It is situated north-east of the city of Preston, at the western end of Longridge Fell, a long ridge above the River Ribble. Its nearest neighbours are Grimsargh and the Roman town of Ribchester , ...

. It is not clear whether he reported Cromwell's advance, but, if he did, Hamilton ignored the report, for on 17 August Monro was half a day's march to the north, Langdale east of Preston, and the main army strung out on the Wigan road, Major-General William Baillie with a body of foot, the rear of the column, being still in Preston. Hamilton, yielding to the importunity of his lieutenant-general, James Livingston, 1st Earl of Callendar

James Livingston, 1st Earl of Callendar

James Livingston, 1st Earl of Callendar , army officer who fought on the Royalist side in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms....

, sent Baillie across the Ribble to follow the main body just as Langdale, with 3,000 foot and 500 horse only, met the first shock of Cromwell's attack on Preston Moor. Hamilton, like Charles at Edgehill, passively shared in, without directing, the Battle of Preston

Battle of Preston (1648)

The Battle of Preston , fought largely at Walton-le-Dale near Preston in Lancashire, resulted in a victory by the troops of Oliver Cromwell over the Royalists and Scots commanded by the Duke of Hamilton...

, and, though Langdale's men fought magnificently, they were after four hours' struggle driven to the Ribble.

Baillie attempted to cover the Ribble and Darwen

River Darwen

The River Darwen is a river running through Darwen and Blackburn in Lancashire.The river was seriously polluted with human and industrial effluent during the Industrial Revolution, up to the early 1970s. The river often changed colour dramatically as a result of paper and paint mills routinely...

bridges on the Wigan road, but Cromwell had forced his way across both before nightfall. Pursuit was at once undertaken, and not relaxed until Hamilton had been driven through Wigan and Winwick

Winwick, Cheshire

Winwick is a village and civil parish in the borough of Warrington in Cheshire, England. Historically within Lancashire, until 1 April 1974, Winwick was administered as part of Lancashire with the rest of north Warrington. It is situated about three miles north of Warrington town centre, near...

to Uttoxeter

Uttoxeter

Uttoxeter is a historic market town in Staffordshire, in the West Midlands region of England. The current population is approximately 13,711, though new developments in the town will increase this figure. Uttoxeter lies close to the River Dove and is near the cities of Stoke-on-Trent, Derby and...

and Ashbourne

Ashbourne, Derbyshire

Ashbourne is a small market town in the Derbyshire Dales, England. It has a population of 10,302.The town advertises itself as 'The Gateway to Dovedale'.- Local customs :...

. There, pressed furiously in rear by Cromwell's horse and held up in front by the militia of the midlands, the remnant of the Scottish army laid down its arms on 25 August. Various attempts were made to raise the Royalist standard in Wales and elsewhere, but Preston was the death-blow. On 28 August, starving and hopeless of relief, the Colchester Royalists surrendered to Lord Fairfax.

Execution of Charles I

The victors in the Second Civil War were not merciful to those who had brought war into the land again. On the evening of the surrender of Colchester, Sir Charles LucasCharles Lucas

Sir Charles Lucas was an English soldier, a Royalist commander in the English Civil War.-Biography:Lucas was the son of Sir Thomas Lucas of Colchester, Essex. As a young man Lucas served in the Netherlands under the command of his brother, and in the "Bishops' Wars" he commanded Cheesea troop of...

and Sir George Lisle

George Lisle

Sir George Lisle was a Royalist leader in the English Civil War. Lisle's execution without trial, following the siege of Colchester, came to be regarded as a serious miscarriage of justice and Lisle himself was seen as a martyr to the Royalist cause.The known facts suggest that Lisle came from...

were shot. Laugharne, Poyer and Powel were sentenced to death, but Poyer alone was executed on 25 April 1649, being the victim selected by lot. Of five prominent Royalist peers who had fallen into the hands of Parliament, three, the Duke of Hamilton, the Earl of Holland, and Lord Capel, one of the Colchester prisoners and a man of high character, were beheaded at Westminster on 9 March. Above all, after long hesitations, even after renewal of negotiations, the Army and the Independents conducted "Pride's Purge

Pride's Purge

Pride’s Purge is an event in December 1648, during the Second English Civil War, when troops under the command of Colonel Thomas Pride forcibly removed from the Long Parliament all those who were not supporters of the Grandees in the New Model Army and the Independents...

" of the House removing their ill-wishers, and created a court for the trial and sentence of King Charles I. At the end of the trial the 59 Commissioners (judges) found Charles I guilty of high treason

High treason

High treason is criminal disloyalty to one's government. Participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplomats, or its secret services for a hostile and foreign power, or attempting to kill its head of state are perhaps...

, as a "tyrant, traitor, murderer and public enemy". He was beheaded on a scaffold in front of the Banqueting House

Banqueting House

In Tudor and Early Stuart English architecture a banqueting house is a separate building reached through pleasure gardens from the main residence, whose use is purely for entertaining. It may be raised for additional air or a vista, and it may be richly decorated, but it contains no bedrooms or...

of the Palace of Whitehall

Palace of Whitehall

The Palace of Whitehall was the main residence of the English monarchs in London from 1530 until 1698 when all except Inigo Jones's 1622 Banqueting House was destroyed by fire...

on 30 January 1649. (After the Restoration

English Restoration

The Restoration of the English monarchy began in 1660 when the English, Scottish and Irish monarchies were all restored under Charles II after the Interregnum that followed the Wars of the Three Kingdoms...

in 1660, the regicides who were still alive and not living in exile were either executed or sentenced to life imprisonment.)

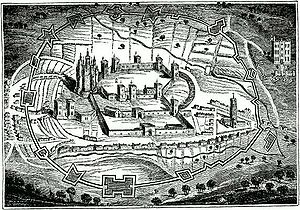

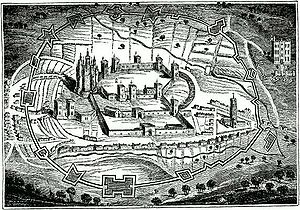

Pontefract Castle

Pontefract CastlePontefract Castle

Pontefract Castle is a castle in the town of Pontefract, in the City of Wakefield, West Yorkshire, England. It was the site of the demise of Richard II of England, and later the place of a series of famous sieges during the English Civil War-History:...

was noted by Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

as "[...] one of the strongest inland garrisons in the kingdom". Even in ruins, the castle held out in the north for the Royalists. Upon the execution of Charles I, the garrison recognised Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

as King and refused to surrender. It was the last Royalist stronghold to surrender. On 24 March 1649, almost two months after Charles was beheaded, the garrison finally capitulated. Parliament had the remains of the castle demolished the same year.

Further reading

- House of Lords Journal Volume 10 19 May 1648: Letter from L. Fairfax, about the Disposal of the Forces, to suppress the Insurrections in Suffolk, Lancashire, and S. Wales; and for Belvoir Castle to be secured

- House of Lords Journal Volume 10 19 May 1648: Disposition of the Remainder of the Forces in England and Wales (not mentioned in the Fairfax letter)