September 1910

Encyclopedia

January

– February

– March

– April

– May

– June

– July

– August

– September – October

– November

– December

.png) The following events occurred in September 1910.

The following events occurred in September 1910.

January 1910

January – February – March – April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in January 1910.-January 1, 1910 :...

– February

February 1910

January – February – March – April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November-DecemberThe following events occurred in February 1910.-February 1, 1910 :...

– March

March 1910

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November -DecemberThe following events occurred in March, 1910:-March 1, 1910 :...

– April

April 1910

January – February – March – April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in April 1910-April 1, 1910 :...

– May

May 1910

January – February – March – April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in May, 1910:-May 1, 1910 :...

– June

June 1910

January – February – March – April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in June 1910:-June 1, 1910 :...

– July

July 1910

January – February – March – April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in July 1910-July 1, 1910 :...

– August

August 1910

January – February – March – April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in August 1910:-August 1, 1910 :...

– September – October

October 1910

January – February – March – April – May – June – July -August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in October 1910:-October 1, 1910 :...

– November

November 1910

January – February – March – April – May – June – July -August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in November 1910:-November 1, 1910 :...

– December

December 1910

January – February – March – April – May – June – July -August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in December 1910:-December 1, 1910 :...

.png)

September 1, 1910 (Thursday)

- Pope Pius XPope Pius XPope Saint Pius X , born Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto, was the 257th Pope of the Catholic Church, serving from 1903 to 1914. He was the first pope since Pope Pius V to be canonized. Pius X rejected modernist interpretations of Catholic doctrine, promoting traditional devotional practices and orthodox...

promulgated the Sacrorum antistitum (Oath Against ModernismOath Against ModernismThe Oath against Modernism was issued by the Roman Catholic Pope, Saint Pius X, on September 1, 1910, and mandated that "all clergy, pastors, confessors, preachers, religious superiors, and professors in philosophical-theological seminaries" should swear to it....

) and directed that all Roman Catholic bishops, priests and teachers take an oath against the ModernistModernism (Roman Catholicism)Modernism refers to theological opinions expressed during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but with influence reaching into the 21st century, which are characterized by a break with the past. Catholic modernists form an amorphous group. The term "modernist" appears in Pope Pius X's 1907...

movement, which called for a departure from following traditional teachings of the Church. The requirement was mandatory until 1967. - The Mormon Tabernacle ChoirMormon Tabernacle ChoirThe Mormon Tabernacle Choir, sometimes colloquially referred to as MoTab, is a Grammy and Emmy Award winning, 360-member, all-volunteer choir. The choir is part of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints . However, the choir is completely self-funded, traveling and producing albums to...

's music was recorded commercially for the first time. The choir's records and CDs have sold millions of copies since then. All music guide: the definitive guide to popular music (Backbeat Books, 2001) p610

September 2, 1910 (Friday)

- The strike of 70,000 of New York's garment workers ended after nine weeks and an estimated $100,000,000 worth of losses secondary to the strike. The major concession won was that each manufacturer was required to have a union shop, and a guarantee of a 50 hour work week—9 hours a day for five days, followed by a 5-hour day.

- Blanche Stuart ScottBlanche Stuart ScottBlanche Stuart Scott , also known as Betty Scott, was possibly the first American woman aviator.-Early life:...

(1889–1970) became the first American woman to make a solo flight in an airplane, taking off from Hammondsport, New YorkHammondsport, New YorkHammondsport is a village in Steuben County, New York, United States. The population was 731 at the 2000 census. The village is named after its founding father.The Village of Hammondsport is in the Town of Urbana and is northeast of Bath, New York....

, after two days of instruction by Glenn CurtissGlenn CurtissGlenn Hammond Curtiss was an American aviation pioneer and a founder of the U.S. aircraft industry. He began his career as a bicycle then motorcycle builder and racer, later also manufacturing engines for airships as early as 1906...

. - Died: Henri RousseauHenri RousseauHenri Julien Félix Rousseau was a French Post-Impressionist painter in the Naïve or Primitive manner. He was also known as Le Douanier , a humorous description of his occupation as a toll collector...

, 66, French post-Impressionist painter

September 3, 1910 (Saturday)

- The boll weevilBoll weevilThe boll weevil is a beetle measuring an average length of six millimeters, which feeds on cotton buds and flowers. Thought to be native to Central America, it migrated into the United States from Mexico in the late 19th century and had infested all U.S. cotton-growing areas by the 1920s,...

, an insect which had destroyed cotton crops since first entering the United States from Mexico, in 1892, was first detected in AlabamaAlabamaAlabama is a state located in the southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama ranks 30th in total land area and ranks second in the size of its inland...

, where cotton production was, at the time, the main industry. The destruction of cotton farming forced farmers to diversify to other crops that, ultimately, were much more profitable—so much so that the citizens of Enterprise, AlabamaEnterprise, AlabamaEnterprise is a city in the southeastern part of Coffee and Dale Counties in the southeastern part of Alabama in the Southern United States. The population was estimated to be 25,909 in the year 2009....

, erected a monument to the pest in 1919. - Born: Maurice PaponMaurice PaponMaurice Papon was a French civil servant, industrial leader and Gaullist politician, who was convicted for crimes against humanity for his participation in the deportation of over 1600 Jews during World War II when he was secretary general for police of the Prefecture of Bordeaux.Papon also...

, French government minister until 1981, later convicted of crimes against humanity, in Gretz-ArmainvilliersGretz-ArmainvilliersGretz-Armainvilliers is a commune in the Seine-et-Marne department in the Île-de-France region in north-central France.-External links:* * *...

(d. February 17, 2007); and Kitty Carlisle, American actress and game show panelist, as Catherine Conn, in New Orleans (d. April 17, 2007)

September 4, 1910 (Sunday)

- Two time-bombs, fashioned from an alarm clock, a detonator and nitroglycerine, exploded in a railroad yard and at a bridge in Peoria, IllinoisPeoria, IllinoisPeoria is the largest city on the Illinois River and the county seat of Peoria County, Illinois, in the United States. It is named after the Peoria tribe. As of the 2010 census, the city was the seventh-most populated in Illinois, with a population of 115,007, and is the third-most populated...

. A third bomb, which had failed to explode, was discovered later. The explosions proved to be a test run for a deadly attack in Los Angeles at the headquarters of the Los Angeles Times.

September 5, 1910 (Monday)

- Marie CurieMarie CurieMarie Skłodowska-Curie was a physicist and chemist famous for her pioneering research on radioactivity. She was the first person honored with two Nobel Prizes—in physics and chemistry...

announced to the French Academy of Sciences at the Sorbonne that she had found a process to isolate pure radiumRadiumRadium is a chemical element with atomic number 88, represented by the symbol Ra. Radium is an almost pure-white alkaline earth metal, but it readily oxidizes on exposure to air, becoming black in color. All isotopes of radium are highly radioactive, with the most stable isotope being radium-226,...

from its naturally occurring salt, radium chlorideRadium chlorideRadium chloride, RaCl2, was the first radium compound to be prepared in a pure state and was the basis of Marie Curie's original separation of radium from barium. The first preparation of radium metal was by the electrolysis of a solution of radium chloride using a mercury...

, making large scale production of the rare element feasible.

September 6, 1910 (Tuesday)

- Voters in the New MexicoNew MexicoNew Mexico is a state located in the southwest and western regions of the United States. New Mexico is also usually considered one of the Mountain States. With a population density of 16 per square mile, New Mexico is the sixth-most sparsely inhabited U.S...

territory selected 68 Republicans and 32 Democrats as delegates for a convention to write a state constitution. - Nicaragua's new President, General Juan Jose Estrada, announced the release of political prisoners and the promise to pay government troops.

- The Tallis Fantasia, a classical piece by British composer Ralph Vaughan WilliamsRalph Vaughan WilliamsRalph Vaughan Williams OM was an English composer of symphonies, chamber music, opera, choral music, and film scores. He was also a collector of English folk music and song: this activity both influenced his editorial approach to the English Hymnal, beginning in 1904, in which he included many...

, was first performed. Vaughn Williams had drawn inspiration from a melody by 16th century composer Thomas TallisThomas TallisThomas Tallis was an English composer. Tallis flourished as a church musician in 16th century Tudor England. He occupies a primary place in anthologies of English church music, and is considered among the best of England's early composers. He is honoured for his original voice in English...

. The melodies continue to be popular in film scores, including The Passion of the ChristThe Passion of the ChristThe Passion of the Christ is a 2004 American drama film directed by Mel Gibson and starring Jim Caviezel as Jesus. It depicts the Passion of Jesus largely according to the New Testament Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John...

. - Died: Elias Fernandez Albano, who had become President of ChilePresident of ChileThe President of the Republic of Chile is both the head of state and the head of government of the Republic of Chile. The President is responsible of the government and state administration...

three weeks earlier on the death of President Pedro MonttPedro MonttPedro Elías Pablo Montt Montt was a Chilean political figure. He served as the president of Chile from 1906 to his death from a probable stroke in 1910...

. Fernandez was succeeded by Emiliano FigueroaEmiliano FigueroaEmiliano Figueroa Larraín was President of Chile from December 23, 1925 until his resignation on May 10, 1927. He also served as Acting president for a few months on 1910.-Biography:...

September 7, 1910 (Wednesday)

- At The HagueThe HagueThe Hague is the capital city of the province of South Holland in the Netherlands. With a population of 500,000 inhabitants , it is the third largest city of the Netherlands, after Amsterdam and Rotterdam...

, the International Court of JusticeInternational Court of JusticeThe International Court of Justice is the primary judicial organ of the United Nations. It is based in the Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands...

resolved the North Atlantic Fisheries Dispute, which had existed for more than 25 years between the United States one one side, and the United Kingdom, Canada and NewfoundlandDominion of NewfoundlandThe Dominion of Newfoundland was a British Dominion from 1907 to 1949 . The Dominion of Newfoundland was situated in northeastern North America along the Atlantic coast and comprised the island of Newfoundland and Labrador on the continental mainland...

on the other. - Died: George W. WeymouthGeorge W. WeymouthGeorge Warren Weymouth was a U.S. Representative from Massachusetts.Born in West Amesbury , Massachusetts, Weymouth attended the public schools and the Merrimac High School. He moved to Fitchburg in 1882 and engaged in the carriage business...

, 60, American businessman and former Congressman (R-Massachusetts), in an auto accident;William Holman HuntWilliam Holman HuntWilliam Holman Hunt OM was an English painter, and one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.-Biography:...

, 83, English painter; and Dr. Emily BlackwellEmily BlackwellEmily Blackwell was the second woman to earn a medical degree at what is now Case Western Reserve University, and the third openly identified woman to earn a medical degree in the United States.-Biography:...

, 83, second American woman to earn an M.D.

September 8, 1910 (Thursday)

- ManhattanManhattanManhattan is the oldest and the most densely populated of the five boroughs of New York City. Located primarily on the island of Manhattan at the mouth of the Hudson River, the boundaries of the borough are identical to those of New York County, an original county of the state of New York...

and Long IslandLong IslandLong Island is an island located in the southeast part of the U.S. state of New York, just east of Manhattan. Stretching northeast into the Atlantic Ocean, Long Island contains four counties, two of which are boroughs of New York City , and two of which are mainly suburban...

were linked by subway as the East River TunnelsEast River TunnelsThe East River Tunnels are 4 single-track railroad tunnels that extend from the eastern end of Pennsylvania Station under 32nd and 33rd Streets in Manhattan and cross the East River to Long Island City in Queens. The tracks carry Long Island Rail Road and Amtrak trains travelling to and from Penn...

opened at ten minutes after midnight. - The city of MirassolMirassolMirassol is a city and municipality in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. The city is located on the north/northwest portion of the state, 463 km from the city of São Paulo and 15 km from São José do Rio Preto...

, BrazilBrazilBrazil , officially the Federative Republic of Brazil , is the largest country in South America. It is the world's fifth largest country, both by geographical area and by population with over 192 million people...

, was incorporated as São Pedro da Mata Una.

September 9, 1910 (Friday)

- The car ferry Pere Marquette No. 18 was midway across Lake MichiganLake MichiganLake Michigan is one of the five Great Lakes of North America and the only one located entirely within the United States. It is the second largest of the Great Lakes by volume and the third largest by surface area, after Lake Superior and Lake Huron...

when it suddenly began taking on water. Because the ferries had been equipped with wireless radio, operator Stephen F. Sczepanek was able to call Pere Marquette No. 17 for assistance. While the ship was being evacuated, it suddenly sank, taking with it 29 people, including Sczepanek and two passengers, but another 33 were saved. - U.S. Treasury Secretary Franklin MacVeaghFranklin MacVeaghFranklin MacVeagh was an American banker and Treasury Secretary.Born in Chester County, Pennsylvania, he graduated from Yale University in 1858, where he was a member of Skull and Bones. He graduated from Columbia Law School in 1864. He worked as a wholesale grocer and lawyer...

outlined a plan to first proposal cut the size of United States currency, from 3 in. by 7 ¼ to 2½ by 6 inches. The size of American banknotes would not be changed until 1929, to the present size of 2.61 by 6.14 inches)

September 10, 1910 (Saturday)

- With his two-year old corporation facing bankruptcy, General MotorsGeneral MotorsGeneral Motors Company , commonly known as GM, formerly incorporated as General Motors Corporation, is an American multinational automotive corporation headquartered in Detroit, Michigan and the world's second-largest automaker in 2010...

Chairman William C. DurantWilliam C. DurantWilliam Crapo "Billy" Durant was a leading pioneer of the United States automobile industry, the founder of General Motors and Chevrolet who created the system of multi-brand holding companies with different lines of cars....

met with financiers at the Chase Manhattan BankChase Manhattan BankJPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., doing business as Chase, is a national bank that constitutes the consumer and commercial banking subsidiary of financial services firm JPMorgan Chase. The bank was known as Chase Manhattan Bank until it merged with J.P. Morgan & Co. in 2000...

in New York, seeking a loan (comparable to $300,000,000 in 2010) to keep the company afloat. The bankers were at first unwilling to lend. At , they listened to Wilfred Leland's account of the success of Cadillac, one of the GM component companies, and agreed to talk further. Ultimately, GM received the loan and avoided bankruptcy until June 1, 2009.

September 11, 1910 (Sunday)

- The largest oil strike, up to that time, in Mexico's history was realized at the Juan Casiano Basin near TampicoTampicoTampico is a city and port in the state of Tamaulipas, in the country of Mexico. It is located in the southeastern part of the state, directly north across the border from Veracruz. Tampico is the third largest city in Tamaulipas, and counts with a population of 309,003. The Metropolitan area of...

. A gusher erupted at Casiano No. 7 at Edward L. DohenyEdward L. DohenyEdward Laurence Doheny was an American oil tycoon, who in 1892, along with business partner Charles A. Canfield, drilled the first successful oil well in the Los Angeles City Oil Field, setting off the petroleum boom in Southern California.At first he was an unsuccessful prospector in the state of...

's Mexican Petroleum Company, producing 60,000 barrels per day, and was the beginning of a new era in which Mexico would become a major oil producer. - NicaraguaNicaraguaNicaragua is the largest country in the Central American American isthmus, bordered by Honduras to the north and Costa Rica to the south. The country is situated between 11 and 14 degrees north of the Equator in the Northern Hemisphere, which places it entirely within the tropics. The Pacific Ocean...

's new PresidentPresident of NicaraguaThe position of President of Nicaragua was created in the Constitution of 1854. From 1825 until the Constitution of 1838 the title of the position was known as Head of State and from 1838 to 1854 as Supreme Director .-Heads of State of Nicaragua within the Federal Republic of Central America...

, Juan José EstradaJuan José EstradaJuan José Estrada Morales was the President of Nicaragua from 30 August 1910 to 9 May 1911.-Biography:He was a member of the Conservative Party of Nicaragua. He began a rebellion against the liberal government of José Santos Zelaya in 1909. Zelaya soon resigned, and in August 1910 the unstable...

, announced that promised elections would not take place for a year. - A cave-inCave-inA cave-in is a collapse of a geologic formation, mine or structure which typically occurs during mining or tunneling. Geologic structures prone to cave-ins include alvar, tsingy and other limestone formations, but can also include lava tubes and a variety of other subsurface rock formations.In...

of the old Erie RailroadErie RailroadThe Erie Railroad was a railroad that operated in New York State, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, originally connecting New York City with Lake Erie...

Tunnel in Jersey City, New JerseyNew JerseyNew Jersey is a state in the Northeastern and Middle Atlantic regions of the United States. , its population was 8,791,894. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York, on the southeast and south by the Atlantic Ocean, on the west by Pennsylvania and on the southwest by Delaware...

, killed eleven workers and injured seven others.

September 12, 1910 (Monday)

- Physicist William David CoolidgeWilliam David CoolidgeWilliam David Coolidge was an American physicist, who made major contributions to X-ray machines. He was the director of the General Electric Research Laboratory and a vice-president of the corporation...

discovered a method of creating ductile tungsten after four years of research at General ElectricGeneral ElectricGeneral Electric Company , or GE, is an American multinational conglomerate corporation incorporated in Schenectady, New York and headquartered in Fairfield, Connecticut, United States...

, making the fragile substance useful for light bulb filaments. - Alice Stebbins WellsAlice Stebbins WellsAlice Stebbins Wells was the first American-born female police officer in the United States, hired in 1910 in Los Angeles...

(1873–1957), first American policewoman in Los Angeles, and perhaps the United States, was sworn in as an LAPD officer. She was initially assigned to the Juvenile Probation unit and retired in 1945. Other sources point to Lola Greene Baldwin, who had been sworn in by the city of Portland, Oregon, "to perform police service", though not as an officer. - Symphony No. 8 (Mahler)Symphony No. 8 (Mahler)The Symphony No. 8 in E-flat major by Gustav Mahler is one of the largest-scale choral works in the classical concert repertoire. Because it requires huge instrumental and vocal forces it is frequently called the "Symphony of a Thousand", although the work is often performed with fewer than a...

, often called Symphony of a Thousand because of the large number of performers required, was first presented. Composer Gustav MahlerGustav MahlerGustav Mahler was a late-Romantic Austrian composer and one of the leading conductors of his generation. He was born in the village of Kalischt, Bohemia, in what was then Austria-Hungary, now Kaliště in the Czech Republic...

himself conducted the first performance, in MunichMunichMunich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

. - Fresno City CollegeFresno City CollegeFresno City College is a community college in Fresno, California. Established in 1910, it was the first community college in California and the second in the nation...

, the second oldest community college in the United States and the first in California, began its first classes. - Our Lady of Victory College, located in Fort Worth, TexasTexasTexas is the second largest U.S. state by both area and population, and the largest state by area in the contiguous United States.The name, based on the Caddo word "Tejas" meaning "friends" or "allies", was applied by the Spanish to the Caddo themselves and to the region of their settlement in...

, began its first classes, with 72 students, and continued operation for 47 years. In 1958, the junior college became part of the University of DallasUniversity of DallasThe University of Dallas is a private, independent Catholic regional university located in Irving, Texas, established in 1956, which is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. According to U.S...

. - Born: Shep FieldsShep FieldsShep Fields was the band leader for the "Shep Fields and His Rippling Rhythm" orchestra during the Big Band era of the 1930s.-Biography:...

, American big band leader (d. 1981)

September 13, 1910 (Tuesday)

- Hazrat Inayat Khan began travels as a missionary to spread the religion of SufismSufismSufism or ' is defined by its adherents as the inner, mystical dimension of Islam. A practitioner of this tradition is generally known as a '...

to the Western world, sailing from MumbaiMumbaiMumbai , formerly known as Bombay in English, is the capital of the Indian state of Maharashtra. It is the most populous city in India, and the fourth most populous city in the world, with a total metropolitan area population of approximately 20.5 million...

to Europe and North America. The International Sufi Movement marks Inayat Khan's mission as the beginning of the organization. - The village of Lampman, SaskatchewanLampman, SaskatchewanLampman is a small town of around 735 people, located in the south east part of Saskatchewan roughly 30 miles northeast of Estevan. It is served by the Lampman Airport....

was incorporated.

September 14, 1910 (Wednesday)

- The Fourth District State Agricultural School, later Arkansas A & M, and now the University of Arkansas at MonticelloUniversity of Arkansas at MonticelloThe University of Arkansas at Monticello is a public university and college for vocational and technical education located in Monticello, Arkansas, United States....

, began instructing its first students. - Thorp Spring Christian College held its first classes. The college, located at Thorp Spring in Hood County, Texas, closed in 1929.

- Pablo Arosemena was chosen as the designado to the office of President of Panama, succeeding the late José Domingo de ObaldíaJosé Domingo de ObaldíaJosé Domingo de Obaldia Gallegos was President of Panama from October 1, 1908 to March 1, 1910 and Vice President in the administration of Manuel Amador....

. - Born: Jack HawkinsJack HawkinsColonel John Edward "Jack" Hawkins CBE was an English actor of the 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s.-Career:Hawkins was born at Lyndhurst Road, Wood Green, Middlesex, the son of master builder Thomas George Hawkins and his wife, Phoebe née Goodman. The youngest of four children in a close-knit family,...

, English film actor, in Wood GreenWood GreenWood Green is a district in north London, England, located in the London Borough of Haringey. It is situated north of Charing Cross. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of the metropolitan centres in Greater London.-History:...

, MiddlesexMiddlesexMiddlesex is one of the historic counties of England and the second smallest by area. The low-lying county contained the wealthy and politically independent City of London on its southern boundary and was dominated by it from a very early time...

(d. 1973); and Bernard Schriever, American rocket scientist, in BremenBremenThe City Municipality of Bremen is a Hanseatic city in northwestern Germany. A commercial and industrial city with a major port on the river Weser, Bremen is part of the Bremen-Oldenburg metropolitan area . Bremen is the second most populous city in North Germany and tenth in Germany.Bremen is...

, Germany (d. 2005) - Died: Huo YuanjiaHuo YuanjiaHuo Yuanjia was a Chinese martial artist and co-founder of Chin Woo Athletic Association, a martial arts school in Shanghai...

, 43, Chinese martial artist, subject of Jet Li film Fearless

September 15, 1910 (Thursday)

- The first elections for the new parliament of the Union of South AfricaUnion of South AfricaThe Union of South Africa is the historic predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into being on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the previously separate colonies of the Cape, Natal, Transvaal and the Orange Free State...

were held, with the Nationalist Party obtaining 67 of the 121 seats. - Woodrow WilsonWoodrow WilsonThomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

, the President of Princeton UniversityPrinceton UniversityPrinceton University is a private research university located in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. The school is one of the eight universities of the Ivy League, and is one of the nine Colonial Colleges founded before the American Revolution....

, was nominated for his first political office, as the convention of the Democratic Party of New Jersey selected him as its candidate for Governor of New JerseyGovernor of New JerseyThe Office of the Governor of New Jersey is the executive branch for the U.S. state of New Jersey. The office of Governor is an elected position, for which elected officials serve four year terms. While individual politicians may serve as many terms as they can be elected to, Governors cannot be...

. In 1912, Governor Wilson would be elected President of the United States.

September 16, 1910 (Friday)

- The patent application for the first outboard motorOutboard motorAn outboard motor is a propulsion system for boats, consisting of a self-contained unit that includes engine, gearbox and propeller or jet drive, designed to be affixed to the outside of the transom and are the most common motorized method of propelling small watercraft...

was filed. Ole EvinrudeOle EvinrudeOle Evinrude, born Ole Evenrudstuen was a Norwegian-American inventor, known for the invention of the first outboard motor with practical commercial application.-Biography:...

, a native of Norway who settled in the United States at Cambridge, WisconsinCambridge, WisconsinCambridge is a village located in Dane and Jefferson Counties in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. The population was 1,100 at the 2000 census.The Dane County portion of Cambridge is part of the Madison Metropolitan Statistical Area, while the Jefferson County portion is part of the...

, had created a "marine propulsion mechanism", a portable motor that could transform a rowboat into a power boat. U.S. Patent No. 1,001,260 would be granted on August 22, 1911. - Bessica Medlar RaicheBessica Medlar RaicheBessica Medlar Raiche was a dentist, businesswoman, and physician, who was the first woman in the United States accredited with flying solo in an airplane...

made the first accredited solo airplane flight by a woman in the United States, flying from Hempstead PlainsHempstead PlainsThe Hempstead Plains is a region of central Long Island in New York state in what is now Nassau County. It was once an open expanse of native grassland estimated to once extend to about . It was separated from the North Shore of Long Island by the Harbor Hill Moraine, later approximately the route...

in New YorkNew YorkNew York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

, two weeks after Blanche Stuart ScottBlanche Stuart ScottBlanche Stuart Scott , also known as Betty Scott, was possibly the first American woman aviator.-Early life:...

's "accidental" solo flight. - Mexico celebrated the centennial of its independence.

- Born: Karl KlingKarl KlingKarl Kling was a motor racing driver and manager from Germany. He participated in 11 Formula One Grands Prix, debuting on 4 July 1954. He achieved 2 podiums, and scored a total of 17 championship points.It is said, that he was born too late and too early...

, German automobile driver and Formula One racer in the 1950s, in GießenGießenGießen, also spelt Giessen is a town in the German federal state of Hesse, capital of both the district of Gießen and the administrative region of Gießen...

(d. 2003); and Lt. Col. Erich KempkaErich KempkaSS-Obersturmbannführer Erich Kempka served as Adolf Hitler's chauffeur from 1934 to April, 1945. He was SS member #2,803 and served in the Allgemeine SS.-Early life:...

, German automobile driver who was Adolf Hitler's chauffeur from 1934 to 1945, in OberhausenOberhausenOberhausen is a city on the river Emscher in the Ruhr Area, Germany, located between Duisburg and Essen . The city hosts the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen and its Gasometer Oberhausen is an anchor point of the European Route of Industrial Heritage. It is also well known for the...

(d. 1975) - Died: Hormuzd RassamHormuzd RassamHormuzd Rassam , was a native Assyrian Assyriologist, British diplomat and traveller who made a number of important discoveries, including the clay tablets that contained the Epic of Gilgamesh, the world's oldest literature...

, 84, Iraqi archaeologist

September 17, 1910 (Saturday)

- The fastest professional baseball game in history took place in a Southern AssociationSouthern AssociationThe Southern Association was a higher-level minor league in American organized baseball from 1901 through 1961. For most of its existence, the Southern Association was two steps below the Major Leagues; it was graded Class A , Class A1 and Class AA...

game in Atlanta. The Mobile Sea GullsMobile BearsThe Mobile Bears were an American minor league baseball team based in Mobile, Alabama. The franchise was a member of the old Southern Association, a high-level circuit that folded after the 1961 season. Mobile joined the SA in 1908 as the Sea Gulls, but changed its name to the Bears in 1918, and...

beat the Atlanta CrackersAtlanta CrackersThe Atlanta Crackers were minor league baseball teams based in Atlanta, Georgia, between 1901 and 1965. The Crackers were Atlanta's home team until the Atlanta Braves moved from Milwaukee in 1966....

, 2–1, in a nine-inning game that was concluded 32 minutes after it started. - By a margin of 198 to 120, voters in Crosby County, Texas, effectively turned the county seatCounty seatA county seat is an administrative center, or seat of government, for a county or civil parish. The term is primarily used in the United States....

of Emma into a ghost townGhost townA ghost town is an abandoned town or city. A town often becomes a ghost town because the economic activity that supported it has failed, or due to natural or human-caused disasters such as floods, government actions, uncontrolled lawlessness, war, or nuclear disasters...

, and moving the county's courts and offices to Crosbyton, TexasCrosbyton, TexasCrosbyton is a city in and the county seat of Crosby County, Texas, United States. The population was 1,874 at the 2000 census. Crosbyton is part of the Lubbock Metropolitan Statistical Area....

. The county courthouse had moved from Estacado to Emma in 1891 by a 109–103 vote. According to the Texas State Historical AssociationTexas State Historical AssociationThe Texas State Historical Association or abbreviated TSHA, is a non-profit educational organization, dedicated to documenting the rich and unique history of Texas. It was founded on March 2, 1897. As of November 2008, TSHA moved from Austin to the University of North Texas in Denton.The executive...

, "A Texas historical marker on State Highway 207 twenty-five miles east of Lubbock is all that remains to mark the site of Emma, the once thriving county seat of Crosby County."

September 18, 1910 (Sunday)

- Brig. Gen. George Owen Squier demonstrated the first system to allow multiplexingMultiplexingThe multiplexed signal is transmitted over a communication channel, which may be a physical transmission medium. The multiplexing divides the capacity of the low-level communication channel into several higher-level logical channels, one for each message signal or data stream to be transferred...

of telephone transmissions, allowing multiple telephone conversations to be transmitted on the same wires, where only one at a time could be made previously. - ChileChileChile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

celebrated the centennial of its independence from Spain.

September 19, 1910 (Monday)

- In ChicagoChicagoChicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

, recently paroled burglar Thomas Jennings broke into a house, killed owner Clarence Hiller, then fled the scene—but not before leaving his fingerprintFingerprintA fingerprint in its narrow sense is an impression left by the friction ridges of a human finger. In a wider use of the term, fingerprints are the traces of an impression from the friction ridges of any part of a human hand. A print from the foot can also leave an impression of friction ridges...

s in the home. Jennings would become the first American to be executed based primarily on fingerprint evidence. Fingerprint evidence had first been used in a murder conviction in 1905 in the United Kingdom, with Alfred and Albert StrattonStratton Brothers caseAlfred Stratton and his brother Albert Ernest were the first men to be convicted in Great Britain for murder based on fingerprint evidence...

being hanged for a double murder.

September 20, 1910 (Tuesday)

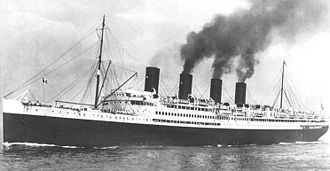

- The SS France, the largest French ocean liner to that time (713 feet long, 24,000 tons and capacity for 2,026 people) was launched. It was the third fastest liner in the world, second only to the Lusitania and the Mauretania.

- West Texas A&M UniversityWest Texas A&M UniversityWest Texas A&M University , part of the Texas A&M University System, is a public university located in Canyon, Texas, a small city south of Amarillo. West Texas A&M opened on September 20, 1910...

, at the time called West Texas State Normal College, began its first classes, with 152 students beginning instruction at the campus in Canyon, TexasCanyon, TexasCanyon is a city in Randall County, Texas, United States. The population was 12,875 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Randall County. It is the home of West Texas A&M University and Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum. Palo Duro Canyon State Park is some twelve miles east of Canyon...

. - Thomas EdisonThomas EdisonThomas Alva Edison was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices that greatly influenced life around the world, including the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and a long-lasting, practical electric light bulb. In addition, he created the world’s first industrial...

applied for a U.S. patent (granted as No. 970,616) on a helicopter of his own invention. The machine was never manufactured.

September 21, 1910 (Wednesday)

- The collision of two interurban streetcars near Kingsland, IndianaKingsland, IndianaKingsland is an unincorporated town in Jefferson Township, Wells County, Indiana....

, killed 42 people.

September 22, 1910 (Thursday)

- The Canadian Public Health AssociationPublic Health GenomicsPublic Health Genomics is the use of genomics information to benefit public health. This is visualized as more effective personalized preventive care and disease treatments with better specificity, targeted to the genetic makeup of each patient...

was created, and began as its first order of business nationwide campaign to vaccinate every child in the nation against smallpox. - Hannah Shapiro, an 18-year old seamstress at the Hart Schaffner & Marx factory in Chicago, led a walkout after the company announced a cut in the piecework rate. At first, only 16 women went on strike, but by October, 40,000 garment workers joined in a work stoppage that would last for five months.

- Died: Azud el-MulkAhmad Shah QajarAhmad Shah Qajar was Shah of Iran from July 16, 1909, to October 31, 1925 and the last of the Qajar dynasty.- Reign :...

, 72, Regent for the Ahmad Shah QajarAhmad Shah QajarAhmad Shah Qajar was Shah of Iran from July 16, 1909, to October 31, 1925 and the last of the Qajar dynasty.- Reign :...

, 12 year old Shah of Persia.

September 23, 1910 (Friday)

- Jorge Chávez Dartnell of Peru became the first person to fly an airplane over the AlpsAlpsThe Alps is one of the great mountain range systems of Europe, stretching from Austria and Slovenia in the east through Italy, Switzerland, Liechtenstein and Germany to France in the west....

, crossing from Switzerland to Italy in 41 minutes, and winning the Milan Committee prize. Sadly, Chavez was fatally injured when his plane crashed while he was gliding in for a landing at DomodossolaDomodossolaDomodossola is a city and comune in the Province of Verbano-Cusio-Ossola, in the region of Piedmont, northern Italy...

, and he died four days later. - Portugal's CortesAssembly of the RepublicThe Assembly of the Republic is the Portuguese parliament. It is located in a historical building in Lisbon, referred to as Palácio de São Bento, the site of an old Benedictine monastery...

was opened by King Manuel IIManuel II of PortugalManuel II , named Manuel Maria Filipe Carlos Amélio Luís Miguel Rafael Gabriel Gonzaga Francisco de Assis Eugénio de Bragança Orleães Sabóia e Saxe-Coburgo-Gotha — , was the last King of Portugal from 1908 to 1910, ascending the throne after the assassination of his father and elder brother Manuel...

, but quickly adjourned when the eligibility of almost half of the elected membership was challenged. Within two weeks, the monarchy was overthrown and a republic was declared. - In CaliforniaCaliforniaCalifornia is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area...

, the Loma Linda Medical CollegeLoma Linda UniversityLoma Linda University is a Seventh-day Adventist coeducational health sciences university located in Loma Linda, California, United States. The University comprises eight schools and the Faculty of Graduate Studies...

began the instruction for its first class of students, graduating its first physicians in 1914. - Born: Elliott RooseveltElliott RooseveltElliott Roosevelt was a United States Army Air Forces officer and an author. Roosevelt was a son of U.S. President Franklin D...

, son of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, who later wrote biographies of both, as well as mystery novels, in Hyde Park, New YorkHyde Park, New YorkHyde Park is a town located in the northwest part of Dutchess County, New York, United States, just north of the city of Poughkeepsie. The town is most famous for being the hometown of U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt....

(d. 1990).

September 24, 1910 (Saturday)

- The National Council in Persia elected Nasir-el-Mulk as the new regentRegentA regent, from the Latin regens "one who reigns", is a person selected to act as head of state because the ruler is a minor, not present, or debilitated. Currently there are only two ruling Regencies in the world, sovereign Liechtenstein and the Malaysian constitutive state of Terengganu...

for the 12-year old Shah, Ahmad Shah QajarAhmad Shah QajarAhmad Shah Qajar was Shah of Iran from July 16, 1909, to October 31, 1925 and the last of the Qajar dynasty.- Reign :...

, by a 40–29 margin over Mustawfi al-Mamalik.

September 25, 1910 (Sunday)

- The future site of the University of British ColumbiaUniversity of British ColumbiaThe University of British Columbia is a public research university. UBC’s two main campuses are situated in Vancouver and in Kelowna in the Okanagan Valley...

was selected by a commission, which chose Point Grey, outside of VancouverVancouverVancouver is a coastal seaport city on the mainland of British Columbia, Canada. It is the hub of Greater Vancouver, which, with over 2.3 million residents, is the third most populous metropolitan area in the country,...

, over Nelson, Kamloops, Vernon and Port Alberni.

September 26, 1910 (Monday)

- K. Ramakrishna Pillai, editor of the newspaper Swadeshabhimani and a journalist who exposed corruption and injustices in the Indian princely state of TravancoreTravancoreKingdom of Travancore was a former Hindu feudal kingdom and Indian Princely State with its capital at Padmanabhapuram or Trivandrum ruled by the Travancore Royal Family. The Kingdom of Travancore comprised most of modern day southern Kerala, Kanyakumari district, and the southernmost parts of...

, was put out of business with his arrest, and permanent banishment, from ThiruvananthapuramThiruvananthapuramThiruvananthapuram , formerly known as Trivandrum, is the capital of the Indian state of Kerala and the headquarters of the Thiruvananthapuram District. It is located on the west coast of India near the extreme south of the mainland...

. He spent the rest of his life in exile to Malabar, dying in 1916.

September 27, 1910 (Tuesday)

- In Mexico, the Chamber of Deputies certified the re-election of Porfirio DíazPorfirio DíazJosé de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori was a Mexican-American War volunteer and French intervention hero, an accomplished general and the President of Mexico continuously from 1876 to 1911, with the exception of a brief term in 1876 when he left Juan N...

as PresidentPresident of MexicoThe President of the United Mexican States is the head of state and government of Mexico. Under the Constitution, the president is also the Supreme Commander of the Mexican armed forces...

, and of Ramón CorralRamón CorralRamón Corral was the Vice President of Mexico under Porfirio Díaz from 1904 until their deposition in 1911.-Early Years:...

as Vice-President. Both men were deposed less than a year into the new six-year term. - Centerville, MinnesotaCenterville, MinnesotaCenterville is a city in Anoka County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 3,792 at the 2010 census.-Geography:According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of , of which, of it is land and of it is water. Main Street / County 14 serves as a main route in the...

, was incorporated as a village

September 28, 1910 (Wednesday)

- Manuel GondraManuel GondraManuel Gondra Pereira was President of Paraguay from November 25, 1910 to January 11, 1911 and from August 15, 1920 to October 31, 1921. He was also an author and a member of the Liberal Party....

was elected President of ParaguayPresident of ParaguayThe President of Paraguay is according to the Paraguayan Constitution the Chief of the Executive branch of the Government of Paraguay...

. - Born: Diosdado MacapagalDiosdado MacapagalDiosdado Pangan Macapagal was the ninth President of the Philippines, serving from 1961 to 1965, and the sixth Vice President, serving from 1957 to 1961. He also served as a member of the House of Representatives, and headed the Constitutional Convention of 1970...

, ninth President of the PhilippinesPresident of the PhilippinesThe President of the Philippines is the head of state and head of government of the Philippines. The president leads the executive branch of the Philippine government and is the commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces of the Philippines...

(1964–65), in LubaoLubao, PampangaLubao is a 1st class municipality in the province of Pampanga, Philippines. According to the latest census, it has a population of 143,058 people in 23,446 households...

(d. 1997); and Wenceslao VinzonsWenceslao VinzonsWenceslao Quinito Vinzons was a Filipino politician and a leader of the armed resistance against the Japanese occupying forces during World War II...

, Philippine leader of resistance against Japanese invasion, in Camarines NorteCamarines NorteCamarines Norte is a province of the Philippines located in the Bicol Region in Luzon. Its capital is Daet and the province borders Quezon to the west and Camarines Sur to the south.-Demographics:...

province (executed 1941)

September 29, 1910 (Thursday)

- The Committee on Urban Conditions Among Negroes was founded in New York City by Mrs. Ruth Standish Baldwin and Dr. George Edmund Haynes. In 1909, the group merged with two other organizations to form the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, and in 1920 shortened its name to the National Urban LeagueNational Urban LeagueThe National Urban League , formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of African Americans and against racial discrimination in the United States. It is the oldest and largest...

. - Died: Winslow HomerWinslow HomerWinslow Homer was an American landscape painter and printmaker, best known for his marine subjects. He is considered one of the foremost painters in 19th century America and a preeminent figure in American art....

, 74, American artist; and Rebecca Harding DavisRebecca Harding DavisRebecca Blaine Harding Davis was an American author and journalist. She is deemed a pioneer of literary realism in American literature. She graduated valedictorian from Washington Female Seminary in Pennsylvania...

, American author

September 30, 1910 (Friday)

- Los Angeles Times bombingLos Angeles Times bombingThe Los Angeles Times bombing was the purposeful dynamiting of the Los Angeles Times building in Los Angeles, California, on October 1, 1910 by a union member belonging to the International Association of Bridge and Structural Iron Workers. The explosion started a fire which killed 21 newspaper...

: American terrorist J.B. McNamara planted a time bomb in a passage beneath the headquarters of the Los Angeles Times newspaper, with 16 sticks of dynamite set to explode after working hours. Two other bombs were placed outside the homes of the Times owner and the secretary of the Merchants and Manufactuers Association. The bomb outside the Times building detonated shortly after on Saturday, triggering an explosion of natural gas lines and setting a fire that killed 20 newspaper employees.