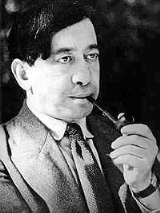

Siegfried Kracauer

Encyclopedia

Siegfried Kracauer was a German

-Jewish writer

, journalist

, sociologist

, cultural critic

, and film theorist

. He has sometimes been associated with the Frankfurt School

of critical theory

.

, Munich

, and Berlin

until 1920.

Near the end of the First World War, he befriended the young Theodor W. Adorno

, to whom he became an early philosophical mentor. In 1964, Adorno recalled that "[f]or years Siegfried Kracauer read the Critique of Pure Reason

with me regularly on Saturday afternoons. I am not exaggerating in the slightest when I say that I owe more to this reading than to my academic teachers. [...] If in my later reading of philosophical texts I was not so much impressed with their unity and systematic consistency as I was concerned with the play of forces at work under the surface of every closed doctrine and viewed the codified philosophies as force fields in each case, it was certainly Kracauer who impelled me to do so."

From 1922 to 1933 he worked as the leading film and literature editor of the Frankfurter Zeitung

(a leading Frankfurt newspaper) as its correspondent in Berlin, where he worked alongside Walter Benjamin

and Ernst Bloch

, among others. Between 1923 and 1925, he wrote an essay entitled Der Detektiv-Roman (The Detective Novel), in which he concerned himself with phenomena from everyday life in modern society.

Kracauer continued this trend over the next few years, building up theoretical methods of analyzing circuses, photography, films, advertising, tourism, city layout, and dance, which he published in 1927 with the work Ornament der Masse (published in English as The Mass Ornament).

In 1930, Kracauer published Die Angestellten (The Salaried Masses), a critical look at the lifestyle and culture of the new class of white-collar

employees. Spiritually homeless, and divorced from custom and tradition, these employees sought refuge in the new "distraction industries" of entertainment. Observers note that many of these lower-middle class employees were quick to adopt Nazism

, three years later. In a contemporary review of Die Angestellten, Benjamin praised the concreteness of Kracauer's analysis, writing that "[t]he entire book is an attempt to grapple with a piece of everyday reality, constructed here and experienced now. Reality is pressed so closely that it is compelled to declare its colors and name names."

Kracauer became increasingly critical of capitalism

(having read the works of Karl Marx

) and eventually broke away from the Frankfurter Zeitung. About this same time (1930), he married Lili Ehrenreich. He was also very critical of Stalinism

and the "terrorist totalitarianism" of the Soviet

government.

With the rise of the Nazis in Germany in 1933, Kracauer migrated to Paris

, and then in 1941 emigrated to the United States

.

From 1941 to 1943 he worked in the Museum of Modern Art

in New York City

, supported by Guggenheim

and Rockefeller scholarships for his work in German film. Eventually, he published From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film

(1947), which traces the birth of Nazism from the cinema of the Weimar Republic

as well as helping lay the foundation of modern film criticism

.

In 1960, he released Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality, which argued that realism

is the most important function of cinema.

In the last years of his life Kracauer worked as a sociologist for different institutes, amongst them in New York as a director of research for applied social sciences at Columbia University

. He died there, in 1966, from the consequences of pneumonia.

His last book is the posthumously published History, the Last Things Before the Last (New York, Oxford University Press, 1969).

wrote that

0

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

-Jewish writer

Writer

A writer is a person who produces literature, such as novels, short stories, plays, screenplays, poetry, or other literary art. Skilled writers are able to use language to portray ideas and images....

, journalist

Journalism

Journalism is the practice of investigation and reporting of events, issues and trends to a broad audience in a timely fashion. Though there are many variations of journalism, the ideal is to inform the intended audience. Along with covering organizations and institutions such as government and...

, sociologist

Sociology

Sociology is the study of society. It is a social science—a term with which it is sometimes synonymous—which uses various methods of empirical investigation and critical analysis to develop a body of knowledge about human social activity...

, cultural critic

Cultural critic

A cultural critic is a critic of a given culture, usually as a whole and typically on a radical basis. There is significant overlap with social and cultural theory.-Terminology:...

, and film theorist

Film theory

Film theory is an academic discipline that aims to explore the essence of the cinema and provides conceptual frameworks for understanding film's relationship to reality, the other arts, individual viewers, and society at large...

. He has sometimes been associated with the Frankfurt School

Frankfurt School

The Frankfurt School refers to a school of neo-Marxist interdisciplinary social theory, particularly associated with the Institute for Social Research at the University of Frankfurt am Main...

of critical theory

Critical theory

Critical theory is an examination and critique of society and culture, drawing from knowledge across the social sciences and humanities. The term has two different meanings with different origins and histories: one originating in sociology and the other in literary criticism...

.

Biography

Born to a Jewish family in Frankfurt am Main, Kracauer studied architecture from 1907 to 1913, eventually obtaining a doctorate in engineering in 1914 and working as an architect in OsnabrückOsnabrück

Osnabrück is a city in Lower Saxony, Germany, some 80 km NNE of Dortmund, 45 km NE of Münster, and some 100 km due west of Hanover. It lies in a valley penned between the Wiehen Hills and the northern tip of the Teutoburg Forest...

, Munich

Munich

Munich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

, and Berlin

Berlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

until 1920.

Near the end of the First World War, he befriended the young Theodor W. Adorno

Theodor W. Adorno

Theodor W. Adorno was a German sociologist, philosopher, and musicologist known for his critical theory of society....

, to whom he became an early philosophical mentor. In 1964, Adorno recalled that "[f]or years Siegfried Kracauer read the Critique of Pure Reason

Critique of Pure Reason

The Critique of Pure Reason by Immanuel Kant, first published in 1781, second edition 1787, is considered one of the most influential works in the history of philosophy. Also referred to as Kant's "first critique," it was followed by the Critique of Practical Reason and the Critique of Judgement...

with me regularly on Saturday afternoons. I am not exaggerating in the slightest when I say that I owe more to this reading than to my academic teachers. [...] If in my later reading of philosophical texts I was not so much impressed with their unity and systematic consistency as I was concerned with the play of forces at work under the surface of every closed doctrine and viewed the codified philosophies as force fields in each case, it was certainly Kracauer who impelled me to do so."

From 1922 to 1933 he worked as the leading film and literature editor of the Frankfurter Zeitung

Frankfurter Zeitung

The Frankfurter Zeitung was a German language newspaper that appeared from 1856 to 1943. It emerged from a market letter that was published in Frankfurt...

(a leading Frankfurt newspaper) as its correspondent in Berlin, where he worked alongside Walter Benjamin

Walter Benjamin

Walter Bendix Schönflies Benjamin was a German-Jewish intellectual, who functioned variously as a literary critic, philosopher, sociologist, translator, radio broadcaster and essayist...

and Ernst Bloch

Ernst Bloch

Ernst Bloch was a German Marxist philosopher.Bloch was influenced by both Hegel and Marx and, as he always confessed, by novelist Karl May. He was also interested in music and art . He established friendships with Georg Lukács, Bertolt Brecht, Kurt Weill and Theodor W. Adorno...

, among others. Between 1923 and 1925, he wrote an essay entitled Der Detektiv-Roman (The Detective Novel), in which he concerned himself with phenomena from everyday life in modern society.

Kracauer continued this trend over the next few years, building up theoretical methods of analyzing circuses, photography, films, advertising, tourism, city layout, and dance, which he published in 1927 with the work Ornament der Masse (published in English as The Mass Ornament).

In 1930, Kracauer published Die Angestellten (The Salaried Masses), a critical look at the lifestyle and culture of the new class of white-collar

White-collar worker

The term white-collar worker refers to a person who performs professional, managerial, or administrative work, in contrast with a blue-collar worker, whose job requires manual labor...

employees. Spiritually homeless, and divorced from custom and tradition, these employees sought refuge in the new "distraction industries" of entertainment. Observers note that many of these lower-middle class employees were quick to adopt Nazism

Nazism

Nazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

, three years later. In a contemporary review of Die Angestellten, Benjamin praised the concreteness of Kracauer's analysis, writing that "[t]he entire book is an attempt to grapple with a piece of everyday reality, constructed here and experienced now. Reality is pressed so closely that it is compelled to declare its colors and name names."

Kracauer became increasingly critical of capitalism

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

(having read the works of Karl Marx

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of social science and the socialist political movement...

) and eventually broke away from the Frankfurter Zeitung. About this same time (1930), he married Lili Ehrenreich. He was also very critical of Stalinism

Stalinism

Stalinism refers to the ideology that Joseph Stalin conceived and implemented in the Soviet Union, and is generally considered a branch of Marxist–Leninist ideology but considered by some historians to be a significant deviation from this philosophy...

and the "terrorist totalitarianism" of the Soviet

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

government.

With the rise of the Nazis in Germany in 1933, Kracauer migrated to Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

, and then in 1941 emigrated to the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

.

From 1941 to 1943 he worked in the Museum of Modern Art

Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art is an art museum in Midtown Manhattan in New York City, on 53rd Street, between Fifth and Sixth Avenues. It has been important in developing and collecting modernist art, and is often identified as the most influential museum of modern art in the world...

in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

, supported by Guggenheim

Guggenheim Fellowship

Guggenheim Fellowships are American grants that have been awarded annually since 1925 by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation to those "who have demonstrated exceptional capacity for productive scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the arts." Each year, the foundation makes...

and Rockefeller scholarships for his work in German film. Eventually, he published From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film

From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film

From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film is a book by film critic and writer Siegfried Kracauer, published in 1947. The book is considered one of the first major studies of German film between World War I and World War II...

(1947), which traces the birth of Nazism from the cinema of the Weimar Republic

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic is the name given by historians to the parliamentary republic established in 1919 in Germany to replace the imperial form of government...

as well as helping lay the foundation of modern film criticism

Film criticism

Film criticism is the analysis and evaluation of films, individually and collectively. In general, this can be divided into journalistic criticism that appears regularly in newspapers, and other popular, mass-media outlets and academic criticism by film scholars that is informed by film theory and...

.

In 1960, he released Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality, which argued that realism

Realism (visual arts)

Realism in the visual arts is a style that depicts the actuality of what the eyes can see. The term is used in different senses in art history; it may mean the same as illusionism, the representation of subjects with visual mimesis or verisimilitude, or may mean an emphasis on the actuality of...

is the most important function of cinema.

In the last years of his life Kracauer worked as a sociologist for different institutes, amongst them in New York as a director of research for applied social sciences at Columbia University

Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York is a private, Ivy League university in Manhattan, New York City. Columbia is the oldest institution of higher learning in the state of New York, the fifth oldest in the United States, and one of the country's nine Colonial Colleges founded before the...

. He died there, in 1966, from the consequences of pneumonia.

His last book is the posthumously published History, the Last Things Before the Last (New York, Oxford University Press, 1969).

Reception

In her book I Lost It at the Movies, film critic Pauline KaelPauline Kael

Pauline Kael was an American film critic who wrote for The New Yorker magazine from 1968 to 1991. Earlier in her career, her work appeared in City Lights, McCall's and The New Republic....

wrote that

Siegfried Kracauer is the sort of man who can't say 'It's a lovely day' without first establishing that it is day, that the term "day" is meaningless without the dialectical concept of 'night,' that both these terms have no meaning unless there is a world in which day and night alternate, and so forth. By the time he has established an epistemological system to support his right to observe that it's a lovely day, our day has been spoiled.

0

Secondary literature

- Oschmann, Dirk, Auszug aus der Innerlichkeit. Das literarische Werk Siegfried Kracauers. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag C. Winter 1999

See also

- ExilliteraturExilliteraturGerman Exilliteratur is the name for a category of books in the German language written by writers of anti-nazi attitude who fled from Nazi Germany between 1933 and 1945...