Stone tool

Encyclopedia

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone

. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric

, particularly Stone Age

cultures that have become extinct. Archaeologists

often study such prehistoric societies, and refer to the study of stone tools as lithic analysis

. Stone has been used to make a wide variety of different tools throughout history, including arrow heads, spearpoints and querns. Stone tools may be made of either ground stone

or chipped stone, and a person who creates tools out of the latter is known as a flintknapper

.

Chipped stone tools are made from cryptocrystalline materials such as chert

or flint

, radiolarite

, chalcedony

, basalt

, quartzite

and obsidian

via a process known as lithic reduction

. One simple form of reduction is to strike stone flake

s from a nucleus (core) of material using a hammerstone

or similar hard hammer fabricator. If the goal of the reduction strategy is to produce flakes, the remnant lithic core

may be discarded once it has become too small to use. In some strategies, however, a flintknapper

reduces the core to a rough unifacial

or bifacial

preform, which is further reduced using soft hammer flaking techniques or by pressure flaking the edges. More complex forms of reduction include the production of highly standardized blades, which can then be fashioned into a variety of tools such as scrapers, knives

, sickle

s and microliths. In general terms, chipped stone tools are nearly ubiquitous in all pre-metal-using societies because they are easily manufactured, the tool stone

is usually plentiful, and they are easy to transport and sharpen.

From the 19th century archaeologists had been turning up prehistoric worked stone tools that appeared to be typologically classifiable into taxa. They referred to these homotaxial groups of stone tools as industries and named them after the type site; for example, Acheulean after St. Acheul, France, and later Oldowan from Olduvai Gorge in Africa. In the earlier 20th century they became complexes and technologies; in the later, technocomplexes.

From the 19th century archaeologists had been turning up prehistoric worked stone tools that appeared to be typologically classifiable into taxa. They referred to these homotaxial groups of stone tools as industries and named them after the type site; for example, Acheulean after St. Acheul, France, and later Oldowan from Olduvai Gorge in Africa. In the earlier 20th century they became complexes and technologies; in the later, technocomplexes.

In 1969 in the 2nd edition of World Prehistory, Grahame Clarke envisioned an evolutionary progression of flint-knapping in which the "dominant lithic technologies" occurred in a fixed sequence from Mode 1 through Mode 5. He assigned to them relative dates: Modes 1 and 2 to the Lower Palaeolithic, 3 to the Middle, 4 to the Advanced and 5 to the Mesolithic. They were not to be conceived, however, as either universal – they did not account for all lithic technology – or synchronous – in effect simultaneously in different regions. Mode 1, for example, was in use in Europe long after it had been replaced by Mode 2 in Africa.

Clarke's scheme was adopted enthusiastically by the archaeological community. One of its advantages was the simplicity of terminology; for example, the Mode 1/Mode 2 Transition. The transitions are currently of greatest interest. Consequently in the literature the stone tools used in the period of the Palaeolithic are divided into four "modes", each of which designate a different form of complexity, and which in most cases followed a rough chronological order.

The earliest stone tools in the life span of the genus Homo

The earliest stone tools in the life span of the genus Homo

are Mode 1 tools, and come from what has been termed the Oldowan Industry, named after the type site (many sites, actually) of Olduvai Gorge

in Tanzania

where they have been found in very large quantities. Oldowan tools were characterised by their simple construction, predominantly using core

forms. These cores were river pebbles, or rocks similar to them, that had been struck by a spherical hammerstone

to cause conchoidal fracture

s removing flakes from one surface, creating an edge and often a sharp tip. The blunt end is the proximal surface; the sharp, the distal. Oldowan is a percussion technology. Grasping the proximal surface, the hominid brought the distal surface down hard on an object he wished to detach or shatter, such as a bone or tuber.

The earliest known Oldowan tools yet found date from 2.6 million years ago, during the Lower Palaeolithic period, and have been uncovered at Gona

in Ethiopia

. After this date, the Oldowan Industry subsequently spread throughout much of Africa, although archaeologists are currently unsure which Hominan species first developed them, with some speculating that it was Australopithecus garhi

, and others believing that it was in fact the more highly evolved Homo habilis

. Homo habilis was the hominin who used the tools for most of the Oldowan in Africa, but at about 1.9-1.8 million years ago Homo erectus

inherited them. The Industry flourished in southern and eastern Africa between 2.6 and 1.7 million years ago, but was also spread out of Africa and into Eurasia

by travelling bands of H. erectus, who took it as far east as Java

by 1.8 million years ago and Northern China by 1.6 million years ago.

Eventually, more complex, Mode 2 tools began to be developed through the Acheulean Industry, named after the site of Saint Acheul in France. The Acheulean was characterised not by the core, but by the biface

, the most notable form of which was the hand axe

. The Acheulean first appears in the archaeological record as early as 1.7 million years ago in the West Turkana area of Kenya

and contemporaneously in southern Africa.

The Leakeys, excavators at Olduvai, defined a "Developed Oldowan" Period in which they believed they saw evidence of an overlap in Oldowan and Acheulean. In their species-specific view of the two industries, Oldowan equated to H. habilis and Acheulean to H. erectus. Developed Oldowan was assigned to habilis and Acheulean to erectus. Subsequent dates on H. erectus pushed the fossils back to well before Acheulean tools; that is, H. erectus must have initially used Mode 1. There was no reason to think, therefore, that Developed Oldowan had to be habilis'; it could have been erectus'. Opponents of the view divide Developed Oldowan between Oldowan and Acheulean. There is no question, however, that habilis and erectus coexisted, as habilis fossils are found as late as 1.4 million years ago. Meanwhile, African H. erectus developed Mode 2. In any case a wave of Mode 2 then spread across Eurasia, resulting in use of both there. H. erectus may not have been the only Hominan to leave Africa; European fossils are sometimes associated with Homo ergaster

, a contemporary of H. erectus in Africa.

In contrast to an Oldowan tool, which is the result of a fortuitous and probably ex tempore operation to obtain one sharp edge on a stone, an Acheulean tool is a planned result of a manufacturing process. The manufacturer begins with a blank, either a larger stone or a slab knocked off a larger rock. From this blank he removes large flakes, to be used as cores. Standing a core on edge on an anvil stone, he hits the exposed edge with centripetal blows of a hard hammer to roughly shape the implement. Then he works it over again, or retouches it, with a soft hammer of wood or bone to produce a tool finely chipped all over consisting of two concave surfaces intersecting in a sharp edge. Such a tool is used for slicing; concussion would destroy the edge and cut the hand.

Some Mode 2 tools are disk-shaped, others ovoid, others leaf-shaped and pointed, and others elongated and pointed at the distal end, with a blunt surface at the proximal end, obviously used for drilling. Mode 2 tools are used for butchering; not being composite (having no haft) they are not very appropriate killing instruments. The killing must have been done some other way. Mode 2 tools are larger than Oldowan. The blank was ported to serve as an ongoing source of flakes until it was finally retouched as a finished tool itself. Edges were often sharpened by further retouching.

in France, where examples were first uncovered in the 1860s. Evolving from the Acheulean, it adopted the Levallois technique

to produce smaller and sharper knife-like tools as well as scrapers. The Mousterian Industry was developed and used primarily by the Neanderthals, a native European and Middle Eastern hominin species.

culture is a good example of mode 4 tool production.

s, which were used in composite tools, mainly fastened to a haft. Examples include the Magdalenian

culture.

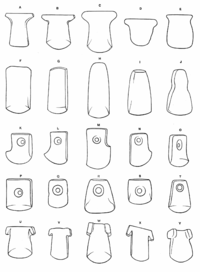

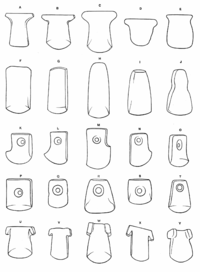

Ground stone tools became important during the Neolithic

Ground stone tools became important during the Neolithic

period. These ground or polished implements are manufactured from larger-grained materials such as basalt

, greenstone

and some forms of rhyolite

which are not suitable for flaking. The greenstone industry was important in the English Lake District, and is known as the Langdale axe industry

. Ground stone implements included adze

s, celt

s, and axe

s, which were manufactured using a labour-intensive, time-consuming method of repeated grinding against an abrasive stone, often using water as a lubricant. Because of their coarse surfaces, some ground stone tools were used for grinding plant foods and were polished not just by intentional shaping, but also by use. Manos are hand stones used in conjunction with metate

s for grinding corn or grain. Polishing increased the intrinsic mechanical strength of the axe. Polished stone axes were important for the widespread clearance of woods and forest during the Neolithic period, when crop and livestock farming developed on a large scale.

During the Neolithic

period, large axes were made from flint nodule

s by chipping a rough shape, a so-called "rough-out". Such products were traded across a wide area. The rough-outs were then polished to give the surface a fine finish to create the axe head. Polishing not only increased the final strength of the product but also meant that the head could penetrate wood more easily.

Such axe heads were needed in large numbers for forest clearance and the establishment of settlements and farmsteads, a characteristic of the Neolithic period. There were many sources of supply, including Grimes Graves

in Suffolk

, Cissbury

in Sussex

and Spiennes

near Mons

in Belgium

to mention but a few. In Britain

, there were numerous small quarries in downland

areas where flint was removed for local use, for example.

Many other rocks were used to make stone axes, including the Langdale axe industry

as well as numerous other sites such as Penmaenmawr

and Tievebulliagh

in Co Antrim, Ulster

. In Langdale, there many outcrop

s of the greenstone

were exploited, and knapped where the stone was extracted. The sites exhibit piles of waste flakes, as well as rejected rough-outs. Polishing improved the mechanical strength of the tools, so increasing their life and effectiveness. Many other tools were developed using the same techniques. Such products were traded across the country and abroad.

gun mechanism in the sixteenth century produced a demand for specially shaped gunflints. The gunflint industry survived until the middle of the twentieth century in some places, including in the English town of Brandon

For specialist purposes glass knives

are still made and used today, particularly for cutting thin section

s for electron microscopy in a technique known as microtomy. Freshly cut blades are always used since the sharpness of the edge is very great. These knives are made from high-quality manufactured glass

, however, not from natural raw materials such as chert or obsidian. Surgical knives made from obsidian

are still used in some delicate surgeries.

Rock (geology)

In geology, rock or stone is a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals and/or mineraloids.The Earth's outer solid layer, the lithosphere, is made of rock. In general rocks are of three types, namely, igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic...

. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric

Prehistory

Prehistory is the span of time before recorded history. Prehistory can refer to the period of human existence before the availability of those written records with which recorded history begins. More broadly, it refers to all the time preceding human existence and the invention of writing...

, particularly Stone Age

Stone Age

The Stone Age is a broad prehistoric period, lasting about 2.5 million years , during which humans and their predecessor species in the genus Homo, as well as the earlier partly contemporary genera Australopithecus and Paranthropus, widely used exclusively stone as their hard material in the...

cultures that have become extinct. Archaeologists

Archaeology

Archaeology, or archeology , is the study of human society, primarily through the recovery and analysis of the material culture and environmental data that they have left behind, which includes artifacts, architecture, biofacts and cultural landscapes...

often study such prehistoric societies, and refer to the study of stone tools as lithic analysis

Lithic analysis

In archaeology, lithic analysis is the analysis of stone tools and other chipped stone artifacts using basic scientific techniques. At its most basic level, lithic analyses involve an analysis of the artifact’s morphology, the measurement of various physical attributes, and examining other visible...

. Stone has been used to make a wide variety of different tools throughout history, including arrow heads, spearpoints and querns. Stone tools may be made of either ground stone

Ground stone

In archaeology, ground stone is a category of stone tool formed by the grinding of a coarse-grained tool stone, either purposely or incidentally. Ground stone tools are usually made of basalt, rhyolite, granite, or other macrocrystalline igneous stones whose coarse structure makes them ideal for...

or chipped stone, and a person who creates tools out of the latter is known as a flintknapper

Flintknapper

Knapping is the shaping of flint, chert, obsidian or other conchoidal fracturing stone through the process of lithic reduction to manufacture stone tools, strikers for flintlock firearms, or to produce flat-faced stones for building or facing walls, and flushwork decoration.- Method :Flintknapping...

.

Chipped stone tools are made from cryptocrystalline materials such as chert

Chert

Chert is a fine-grained silica-rich microcrystalline, cryptocrystalline or microfibrous sedimentary rock that may contain small fossils. It varies greatly in color , but most often manifests as gray, brown, grayish brown and light green to rusty red; its color is an expression of trace elements...

or flint

Flint

Flint is a hard, sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as a variety of chert. It occurs chiefly as nodules and masses in sedimentary rocks, such as chalks and limestones. Inside the nodule, flint is usually dark grey, black, green, white, or brown in colour, and...

, radiolarite

Radiolarite

Radiolarite is a siliceous, comparatively hard, fine-grained, chert-like, and homogeneous sedimentary rock that is composed predominantly of the microscopic remains of radiolarians. This term is also used for indurated radiolarian oozes and sometimes as a synonym of radiolarian earth...

, chalcedony

Chalcedony

Chalcedony is a cryptocrystalline form of silica, composed of very fine intergrowths of the minerals quartz and moganite. These are both silica minerals, but they differ in that quartz has a trigonal crystal structure, while moganite is monoclinic...

, basalt

Basalt

Basalt is a common extrusive volcanic rock. It is usually grey to black and fine-grained due to rapid cooling of lava at the surface of a planet. It may be porphyritic containing larger crystals in a fine matrix, or vesicular, or frothy scoria. Unweathered basalt is black or grey...

, quartzite

Quartzite

Quartzite is a hard metamorphic rock which was originally sandstone. Sandstone is converted into quartzite through heating and pressure usually related to tectonic compression within orogenic belts. Pure quartzite is usually white to gray, though quartzites often occur in various shades of pink...

and obsidian

Obsidian

Obsidian is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed as an extrusive igneous rock.It is produced when felsic lava extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimum crystal growth...

via a process known as lithic reduction

Lithic reduction

Lithic reduction involves the use of a hard hammer precursor, such as a hammerstone, a soft hammer fabricator , or a wood or antler punch to detach lithic flakes from a lump of tool stone called a lithic core . As flakes are detached in sequence, the original mass of stone is reduced; hence the...

. One simple form of reduction is to strike stone flake

Lithic flake

In archaeology, a lithic flake is a "portion of rock removed from an objective piece by percussion or pressure," and may also be referred to as a chip or spall, or collectively as debitage. The objective piece, or the rock being reduced by the removal of flakes, is known as a core. Once the proper...

s from a nucleus (core) of material using a hammerstone

Hammerstone

In archaeology, a hammerstone is a hard cobble used to strike off lithic flakes from a lump of tool stone during the process of lithic reduction. The hammerstone is a rather universal stone tool which appeared early in most regions of the world including Europe, India and North America...

or similar hard hammer fabricator. If the goal of the reduction strategy is to produce flakes, the remnant lithic core

Lithic core

In archaeology, a lithic core is a distinctive artifact that results from the practice of lithic reduction. In this sense, a core is the scarred nucleus resulting from the detachment of one or more flakes from a lump of source material or tool stone, usually by using a hard hammer percussor such...

may be discarded once it has become too small to use. In some strategies, however, a flintknapper

Flintknapper

Knapping is the shaping of flint, chert, obsidian or other conchoidal fracturing stone through the process of lithic reduction to manufacture stone tools, strikers for flintlock firearms, or to produce flat-faced stones for building or facing walls, and flushwork decoration.- Method :Flintknapping...

reduces the core to a rough unifacial

Uniface

In archeology, a uniface is a specific type of stone tool that has been flaked on one surface only. There are two general classes of uniface tools: modified flakes—and formalized tools, which display deliberate, systematic modification of the marginal edges, evidently formed for a specific...

or bifacial

Biface

In archaeology, a biface is a two-sided stone tool and is used as a multi purposes knife, manufactured through a process of lithic reduction, that displays flake scars on both sides. A profile view of the final product tends to exhibit a lenticular shape...

preform, which is further reduced using soft hammer flaking techniques or by pressure flaking the edges. More complex forms of reduction include the production of highly standardized blades, which can then be fashioned into a variety of tools such as scrapers, knives

Knife

A knife is a cutting tool with an exposed cutting edge or blade, hand-held or otherwise, with or without a handle. Knives were used at least two-and-a-half million years ago, as evidenced by the Oldowan tools...

, sickle

Sickle

A sickle is a hand-held agricultural tool with a variously curved blade typically used for harvesting grain crops or cutting succulent forage chiefly for feeding livestock . Sickles have also been used as weapons, either in their original form or in various derivations.The diversity of sickles that...

s and microliths. In general terms, chipped stone tools are nearly ubiquitous in all pre-metal-using societies because they are easily manufactured, the tool stone

Tool stone

The term tool stone has multiple meanings.In archaeology, a tool stone is a type of stone that is used to manufacture stone tools.Alternatively, the term can be used to refer to stones used as the raw material for tools....

is usually plentiful, and they are easy to transport and sharpen.

Evolutionary development of technocomplexes

In 1969 in the 2nd edition of World Prehistory, Grahame Clarke envisioned an evolutionary progression of flint-knapping in which the "dominant lithic technologies" occurred in a fixed sequence from Mode 1 through Mode 5. He assigned to them relative dates: Modes 1 and 2 to the Lower Palaeolithic, 3 to the Middle, 4 to the Advanced and 5 to the Mesolithic. They were not to be conceived, however, as either universal – they did not account for all lithic technology – or synchronous – in effect simultaneously in different regions. Mode 1, for example, was in use in Europe long after it had been replaced by Mode 2 in Africa.

Clarke's scheme was adopted enthusiastically by the archaeological community. One of its advantages was the simplicity of terminology; for example, the Mode 1/Mode 2 Transition. The transitions are currently of greatest interest. Consequently in the literature the stone tools used in the period of the Palaeolithic are divided into four "modes", each of which designate a different form of complexity, and which in most cases followed a rough chronological order.

Mode I: The Oldowan Industry

Homo

Homo may refer to:*the Greek prefix ὅμο-, meaning "the same"*the Latin for man, human being*Homo, the taxonomical genus including modern humans...

are Mode 1 tools, and come from what has been termed the Oldowan Industry, named after the type site (many sites, actually) of Olduvai Gorge

Olduvai Gorge

The Olduvai Gorge is a steep-sided ravine in the Great Rift Valley that stretches through eastern Africa. It is in the eastern Serengeti Plains in northern Tanzania and is about long. It is located 45 km from the Laetoli archaeological site...

in Tanzania

Tanzania

The United Republic of Tanzania is a country in East Africa bordered by Kenya and Uganda to the north, Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west, and Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique to the south. The country's eastern borders lie on the Indian Ocean.Tanzania is a state...

where they have been found in very large quantities. Oldowan tools were characterised by their simple construction, predominantly using core

Lithic core

In archaeology, a lithic core is a distinctive artifact that results from the practice of lithic reduction. In this sense, a core is the scarred nucleus resulting from the detachment of one or more flakes from a lump of source material or tool stone, usually by using a hard hammer percussor such...

forms. These cores were river pebbles, or rocks similar to them, that had been struck by a spherical hammerstone

Hammerstone

In archaeology, a hammerstone is a hard cobble used to strike off lithic flakes from a lump of tool stone during the process of lithic reduction. The hammerstone is a rather universal stone tool which appeared early in most regions of the world including Europe, India and North America...

to cause conchoidal fracture

Conchoidal fracture

Conchoidal fracture describes the way that brittle materials break when they do not follow any natural planes of separation. Materials that break in this way include flint and other fine-grained minerals, as well as most amorphous solids, such as obsidian and other types of glass.Conchoidal...

s removing flakes from one surface, creating an edge and often a sharp tip. The blunt end is the proximal surface; the sharp, the distal. Oldowan is a percussion technology. Grasping the proximal surface, the hominid brought the distal surface down hard on an object he wished to detach or shatter, such as a bone or tuber.

The earliest known Oldowan tools yet found date from 2.6 million years ago, during the Lower Palaeolithic period, and have been uncovered at Gona

Gona

-History:Gona was the site of an Anglican church and mission.During World War II, Imperial Japanese troops invaded on 21–22 July 1942 and established it as a base. Three missionaries were captured at Gona, Father James Benson, May Hayman and Mavis Parkins. The two women and a six year old boy were...

in Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Ethiopia , officially known as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is the second-most populous nation in Africa, with over 82 million inhabitants, and the tenth-largest by area, occupying 1,100,000 km2...

. After this date, the Oldowan Industry subsequently spread throughout much of Africa, although archaeologists are currently unsure which Hominan species first developed them, with some speculating that it was Australopithecus garhi

Australopithecus garhi

Australopithecus garhi is a gracile australopithecine species whose fossils were discovered in 1996 by a research team led by Ethiopian paleontologist Berhane Asfaw and Tim White, an American paleontologist. The hominin remains are believed to be a human ancestor species and the final missing link...

, and others believing that it was in fact the more highly evolved Homo habilis

Homo habilis

Homo habilis is a species of the genus Homo, which lived from approximately at the beginning of the Pleistocene period. The discovery and description of this species is credited to both Mary and Louis Leakey, who found fossils in Tanzania, East Africa, between 1962 and 1964. Homo habilis Homo...

. Homo habilis was the hominin who used the tools for most of the Oldowan in Africa, but at about 1.9-1.8 million years ago Homo erectus

Homo erectus

Homo erectus is an extinct species of hominid that lived from the end of the Pliocene epoch to the later Pleistocene, about . The species originated in Africa and spread as far as India, China and Java. There is still disagreement on the subject of the classification, ancestry, and progeny of H...

inherited them. The Industry flourished in southern and eastern Africa between 2.6 and 1.7 million years ago, but was also spread out of Africa and into Eurasia

Eurasia

Eurasia is a continent or supercontinent comprising the traditional continents of Europe and Asia ; covering about 52,990,000 km2 or about 10.6% of the Earth's surface located primarily in the eastern and northern hemispheres...

by travelling bands of H. erectus, who took it as far east as Java

Java

Java is an island of Indonesia. With a population of 135 million , it is the world's most populous island, and one of the most densely populated regions in the world. It is home to 60% of Indonesia's population. The Indonesian capital city, Jakarta, is in west Java...

by 1.8 million years ago and Northern China by 1.6 million years ago.

Mode II: The Acheulean Industry

Eventually, more complex, Mode 2 tools began to be developed through the Acheulean Industry, named after the site of Saint Acheul in France. The Acheulean was characterised not by the core, but by the biface

Biface

In archaeology, a biface is a two-sided stone tool and is used as a multi purposes knife, manufactured through a process of lithic reduction, that displays flake scars on both sides. A profile view of the final product tends to exhibit a lenticular shape...

, the most notable form of which was the hand axe

Hand axe

A hand axe is a bifacial Stone tool typical of the lower and middle Palaeolithic , and is the longest-used tool of human history.-Distribution:...

. The Acheulean first appears in the archaeological record as early as 1.7 million years ago in the West Turkana area of Kenya

Kenya

Kenya , officially known as the Republic of Kenya, is a country in East Africa that lies on the equator, with the Indian Ocean to its south-east...

and contemporaneously in southern Africa.

The Leakeys, excavators at Olduvai, defined a "Developed Oldowan" Period in which they believed they saw evidence of an overlap in Oldowan and Acheulean. In their species-specific view of the two industries, Oldowan equated to H. habilis and Acheulean to H. erectus. Developed Oldowan was assigned to habilis and Acheulean to erectus. Subsequent dates on H. erectus pushed the fossils back to well before Acheulean tools; that is, H. erectus must have initially used Mode 1. There was no reason to think, therefore, that Developed Oldowan had to be habilis'; it could have been erectus'. Opponents of the view divide Developed Oldowan between Oldowan and Acheulean. There is no question, however, that habilis and erectus coexisted, as habilis fossils are found as late as 1.4 million years ago. Meanwhile, African H. erectus developed Mode 2. In any case a wave of Mode 2 then spread across Eurasia, resulting in use of both there. H. erectus may not have been the only Hominan to leave Africa; European fossils are sometimes associated with Homo ergaster

Homo ergaster

Homo ergaster is an extinct chronospecies of Homo that lived in eastern and southern Africa during the early Pleistocene, about 2.5–1.7 million years ago.There is still disagreement on the subject of the classification, ancestry, and progeny of H...

, a contemporary of H. erectus in Africa.

In contrast to an Oldowan tool, which is the result of a fortuitous and probably ex tempore operation to obtain one sharp edge on a stone, an Acheulean tool is a planned result of a manufacturing process. The manufacturer begins with a blank, either a larger stone or a slab knocked off a larger rock. From this blank he removes large flakes, to be used as cores. Standing a core on edge on an anvil stone, he hits the exposed edge with centripetal blows of a hard hammer to roughly shape the implement. Then he works it over again, or retouches it, with a soft hammer of wood or bone to produce a tool finely chipped all over consisting of two concave surfaces intersecting in a sharp edge. Such a tool is used for slicing; concussion would destroy the edge and cut the hand.

Some Mode 2 tools are disk-shaped, others ovoid, others leaf-shaped and pointed, and others elongated and pointed at the distal end, with a blunt surface at the proximal end, obviously used for drilling. Mode 2 tools are used for butchering; not being composite (having no haft) they are not very appropriate killing instruments. The killing must have been done some other way. Mode 2 tools are larger than Oldowan. The blank was ported to serve as an ongoing source of flakes until it was finally retouched as a finished tool itself. Edges were often sharpened by further retouching.

Mode III: The Mousterian Industry

Eventually, the Acheulean in Europe was replaced by a lithic technology known as the Mousterian Industry, which was named after the site of Le MoustierLe Moustier

Le Moustier is an archeological site consisting of two rock shelters in Peyzac-le-Moustier, Dordogne, France. It is known for a fossilized skull of the species Homo neanderthalensis that was discovered in 1909...

in France, where examples were first uncovered in the 1860s. Evolving from the Acheulean, it adopted the Levallois technique

Levallois technique

The Levallois technique is a name given by archaeologists to a distinctive type of stone knapping developed by precursors to modern humans during the Palaeolithic period....

to produce smaller and sharper knife-like tools as well as scrapers. The Mousterian Industry was developed and used primarily by the Neanderthals, a native European and Middle Eastern hominin species.

Mode IV: The Aurignacian Industry

The long blades (rather than flakes) of the Upper Palaeolithic Mode 4 industries appeared during the Upper Palaeolithic. The AurignacianAurignacian

The Aurignacian culture is an archaeological culture of the Upper Palaeolithic, located in Europe and southwest Asia. It lasted broadly within the period from ca. 45,000 to 35,000 years ago in terms of conventional radiocarbon dating, or between ca. 47,000 and 41,000 years ago in terms of the most...

culture is a good example of mode 4 tool production.

Mode V: The Microlithic Industries

Mode 5 stone tools involve the production of MicrolithMicrolith

A microlith is a small stone tool usually made of flint or chert and typically a centimetre or so in length and half a centimetre wide. It is produced from either a small blade or a larger blade-like piece of flint by abrupt or truncated retouching, which leaves a very typical piece of waste,...

s, which were used in composite tools, mainly fastened to a haft. Examples include the Magdalenian

Magdalenian

The Magdalenian , refers to one of the later cultures of the Upper Paleolithic in western Europe, dating from around 17,000 BP to 9,000 BP...

culture.

Neolithic industries

Neolithic

The Neolithic Age, Era, or Period, or New Stone Age, was a period in the development of human technology, beginning about 9500 BC in some parts of the Middle East, and later in other parts of the world. It is traditionally considered as the last part of the Stone Age...

period. These ground or polished implements are manufactured from larger-grained materials such as basalt

Basalt

Basalt is a common extrusive volcanic rock. It is usually grey to black and fine-grained due to rapid cooling of lava at the surface of a planet. It may be porphyritic containing larger crystals in a fine matrix, or vesicular, or frothy scoria. Unweathered basalt is black or grey...

, greenstone

Greenstone (archaeology)

Greenstone is a common generic term for valuable, green-hued minerals and metamorphosed igneous rocks and stones, that were used in the fashioning of hardstone carvings such as jewelry, statuettes, ritual tools, and various other artefacts in early cultures...

and some forms of rhyolite

Rhyolite

This page is about a volcanic rock. For the ghost town see Rhyolite, Nevada, and for the satellite system, see Rhyolite/Aquacade.Rhyolite is an igneous, volcanic rock, of felsic composition . It may have any texture from glassy to aphanitic to porphyritic...

which are not suitable for flaking. The greenstone industry was important in the English Lake District, and is known as the Langdale axe industry

Langdale axe industry

The Langdale axe industry is the name given by archaeologists to the centre of a specialised stone tool manufacturing at Great Langdale in England's Lake District during the Neolithic period .The area has outcrops of fine-grained greenstone suitable for making polished axes which have been...

. Ground stone implements included adze

Adze

An adze is a tool used for smoothing or carving rough-cut wood in hand woodworking. Generally, the user stands astride a board or log and swings the adze downwards towards his feet, chipping off pieces of wood, moving backwards as they go and leaving a relatively smooth surface behind...

s, celt

Celt (tool)

Celt is an archaeological term used to describe long thin prehistoric stone or bronze adzes, other axe-like tools, and hoes.-Etymology:The term "celt" came about from what was very probably a copyist's error in many medieval manuscript copies of Job 19:24 in the Latin Vulgate Bible, which became...

s, and axe

Axe

The axe, or ax, is an implement that has been used for millennia to shape, split and cut wood; to harvest timber; as a weapon; and as a ceremonial or heraldic symbol...

s, which were manufactured using a labour-intensive, time-consuming method of repeated grinding against an abrasive stone, often using water as a lubricant. Because of their coarse surfaces, some ground stone tools were used for grinding plant foods and were polished not just by intentional shaping, but also by use. Manos are hand stones used in conjunction with metate

Metate

A metate is a mortar, a ground stone tool used for processing grain and seeds. In traditional Mesoamerican culture, metates were typically used by women who would grind calcified maize and other organic materials during food preparation...

s for grinding corn or grain. Polishing increased the intrinsic mechanical strength of the axe. Polished stone axes were important for the widespread clearance of woods and forest during the Neolithic period, when crop and livestock farming developed on a large scale.

During the Neolithic

Neolithic

The Neolithic Age, Era, or Period, or New Stone Age, was a period in the development of human technology, beginning about 9500 BC in some parts of the Middle East, and later in other parts of the world. It is traditionally considered as the last part of the Stone Age...

period, large axes were made from flint nodule

Nodule (geology)

A nodule in petrology or mineralogy is a secondary structure, generally spherical or irregularly rounded in shape. Nodules are typically solid replacement bodies of chert or iron oxides formed during diagenesis of a sedimentary rock...

s by chipping a rough shape, a so-called "rough-out". Such products were traded across a wide area. The rough-outs were then polished to give the surface a fine finish to create the axe head. Polishing not only increased the final strength of the product but also meant that the head could penetrate wood more easily.

Such axe heads were needed in large numbers for forest clearance and the establishment of settlements and farmsteads, a characteristic of the Neolithic period. There were many sources of supply, including Grimes Graves

Grimes Graves

Grime's Graves is a large Neolithic flint mining complex near Brandon in England close to the border between Norfolk and Suffolk. It was worked between around circa 3000 BC and circa 1900 BC, although production may have continued well into the Bronze and Iron Ages owing to the low cost of flint...

in Suffolk

Suffolk

Suffolk is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in East Anglia, England. It has borders with Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south. The North Sea lies to the east...

, Cissbury

Cissbury

Cissbury is the name of a prehistoric site near the village of Findon around 5 miles north of Worthing in the English county of West Sussex. The site is managed by the National Trust....

in Sussex

Sussex

Sussex , from the Old English Sūþsēaxe , is an historic county in South East England corresponding roughly in area to the ancient Kingdom of Sussex. It is bounded on the north by Surrey, east by Kent, south by the English Channel, and west by Hampshire, and is divided for local government into West...

and Spiennes

Spiennes

Spiennes is a Walloon village in the municipality of Mons, Belgium.It is well known for its neolithic flint mines, which are on the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites since 2000....

near Mons

Mons

Mons is a Walloon city and municipality located in the Belgian province of Hainaut, of which it is the capital. The Mons municipality includes the old communes of Cuesmes, Flénu, Ghlin, Hyon, Nimy, Obourg, Baudour , Jemappes, Ciply, Harmignies, Harveng, Havré, Maisières, Mesvin, Nouvelles,...

in Belgium

Belgium

Belgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

to mention but a few. In Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

, there were numerous small quarries in downland

Downland

A downland is an area of open chalk hills. This term is especially used to describe the chalk countryside in southern England. Areas of downland are often referred to as Downs....

areas where flint was removed for local use, for example.

Many other rocks were used to make stone axes, including the Langdale axe industry

Langdale axe industry

The Langdale axe industry is the name given by archaeologists to the centre of a specialised stone tool manufacturing at Great Langdale in England's Lake District during the Neolithic period .The area has outcrops of fine-grained greenstone suitable for making polished axes which have been...

as well as numerous other sites such as Penmaenmawr

Penmaenmawr

PenmaenmawrConwyPenmaenmawr is a town in the parish of Dwygyfylchi, in Conwy County Borough, Wales. The population was 3857 in 2001. It is a quarrying town, though the latter is no longer a major employer, on the North Wales coast between Conwy and Llanfairfechan.The town was bypassed by the A55...

and Tievebulliagh

Tievebulliagh

Tievebulliagh is a 402m high mountain in the Glens of Antrim, Northern Ireland. It forms part of the watershed between Glenann to the north and Glenballyeamon to the south...

in Co Antrim, Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

. In Langdale, there many outcrop

Outcrop

An outcrop is a visible exposure of bedrock or ancient superficial deposits on the surface of the Earth. -Features:Outcrops do not cover the majority of the Earth's land surface because in most places the bedrock or superficial deposits are covered by a mantle of soil and vegetation and cannot be...

s of the greenstone

Greenstone (archaeology)

Greenstone is a common generic term for valuable, green-hued minerals and metamorphosed igneous rocks and stones, that were used in the fashioning of hardstone carvings such as jewelry, statuettes, ritual tools, and various other artefacts in early cultures...

were exploited, and knapped where the stone was extracted. The sites exhibit piles of waste flakes, as well as rejected rough-outs. Polishing improved the mechanical strength of the tools, so increasing their life and effectiveness. Many other tools were developed using the same techniques. Such products were traded across the country and abroad.

Modern uses

The invention of the flintlockFlintlock

Flintlock is the general term for any firearm based on the flintlock mechanism. The term may also apply to the mechanism itself. Introduced at the beginning of the 17th century, the flintlock rapidly replaced earlier firearm-ignition technologies, such as the doglock, matchlock and wheellock...

gun mechanism in the sixteenth century produced a demand for specially shaped gunflints. The gunflint industry survived until the middle of the twentieth century in some places, including in the English town of Brandon

Brandon, Suffolk

Brandon is a small town and civil parish in the English county of Suffolk. It is in the Forest Heath local government district.Brandon is located in the Breckland area on the border of Suffolk with the adjoining county of Norfolk...

For specialist purposes glass knives

Glass knife

A glass knife is a knife with a blade composed of glass. The cutting edge of a glass knife is formed from a fracture line, and is extremely sharp....

are still made and used today, particularly for cutting thin section

Thin section

In optical mineralogy and petrography, a thin section is a laboratory preparation of a rock, mineral, soil, pottery, bones, or even metal sample for use with a polarizing petrographic microscope, electron microscope and electron microprobe. A thin sliver of rock is cut from the sample with a...

s for electron microscopy in a technique known as microtomy. Freshly cut blades are always used since the sharpness of the edge is very great. These knives are made from high-quality manufactured glass

Glass

Glass is an amorphous solid material. Glasses are typically brittle and optically transparent.The most familiar type of glass, used for centuries in windows and drinking vessels, is soda-lime glass, composed of about 75% silica plus Na2O, CaO, and several minor additives...

, however, not from natural raw materials such as chert or obsidian. Surgical knives made from obsidian

Obsidian

Obsidian is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed as an extrusive igneous rock.It is produced when felsic lava extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimum crystal growth...

are still used in some delicate surgeries.

Tool stone

In archaeology, a tool stone is a type of stone that is used to manufacture stone tools. Alternatively, the term can be used to refer to stones used as the raw material for tools.See also

- Lithic technologyLithic TechnologyIn archeology, lithic technology refers to a broad array of techniques and styles to produce usable tools from various types of stone. The earliest stone tools were recovered from modern Ethiopia and were dated to between two-million and three-million years old...

- Knapping

- FlintFlintFlint is a hard, sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as a variety of chert. It occurs chiefly as nodules and masses in sedimentary rocks, such as chalks and limestones. Inside the nodule, flint is usually dark grey, black, green, white, or brown in colour, and...

- Flint tool

- ManuportManuportIn archaeology and anthropology, a manuport is a natural object which has been moved from its original context by human agency but otherwise remains unmodified. The word derives from the Latin words manus, meaning 'hand' and portare, meaning 'to carry'.Examples include stones or shells moved from...

- Langdale axe industryLangdale axe industryThe Langdale axe industry is the name given by archaeologists to the centre of a specialised stone tool manufacturing at Great Langdale in England's Lake District during the Neolithic period .The area has outcrops of fine-grained greenstone suitable for making polished axes which have been...

- CissburyCissburyCissbury is the name of a prehistoric site near the village of Findon around 5 miles north of Worthing in the English county of West Sussex. The site is managed by the National Trust....

- Grimes GravesGrimes GravesGrime's Graves is a large Neolithic flint mining complex near Brandon in England close to the border between Norfolk and Suffolk. It was worked between around circa 3000 BC and circa 1900 BC, although production may have continued well into the Bronze and Iron Ages owing to the low cost of flint...

- Great OrmeGreat OrmeThe Great Orme is a prominent limestone headland on the north coast of Wales situated in Llandudno. It is referred to as Cyngreawdr Fynydd in a poem by the 12th century poet Gwalchmai ap Meilyr...

- PenmaenmawrPenmaenmawrPenmaenmawrConwyPenmaenmawr is a town in the parish of Dwygyfylchi, in Conwy County Borough, Wales. The population was 3857 in 2001. It is a quarrying town, though the latter is no longer a major employer, on the North Wales coast between Conwy and Llanfairfechan.The town was bypassed by the A55...

- SpiennesSpiennesSpiennes is a Walloon village in the municipality of Mons, Belgium.It is well known for its neolithic flint mines, which are on the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites since 2000....

- TievebulliaghTievebulliaghTievebulliagh is a 402m high mountain in the Glens of Antrim, Northern Ireland. It forms part of the watershed between Glenann to the north and Glenballyeamon to the south...

- Chaîne opératoireChaîne opératoireChaîne opératoire is a term used in archaeology that denotes the social acts involved in production, use, and disposal of an artifact, such as a stone tool. The concept was introduced by the French archaeologist André Leroi-Gourhan....