.gif)

Symphony No. 6 (Dvorák)

Encyclopedia

Czech composer Antonín Dvořák

(1841-1904) composed his Symphony No. 6 in D major, Op. 60, B. 112, in 1880. It is dedicated to Hans Richter

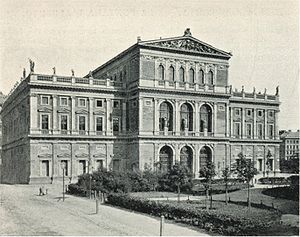

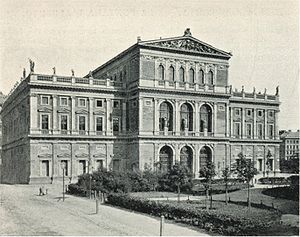

, who was the conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

. With a performance time of approximately 40 minutes, the four-movement piece was one of the first of Dvořák’s large symphonic works to draw international attention. In it, he manages to capture a bit of the Czech national style within a standard Germanic classical-romantic form.

, the climate and reception of Dvořák’s earlier works in Vienna

should be taken into consideration.

In late 1879, Hans Richter

conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in a subscription concert that included the Third Slavonic Rhapsody. According to Dvořák, in a letter dated 23 November, 1879,

Music historians

have made various conclusions regarding what this letter implies about Dvořák’s reception in Vienna. Dvořák scholar John Clapham interprets this letter to say that the audience at the concert responded with a warm ovation, and that Richter was pleased with the work. Yet, according to David Brodbeck, this account probably only describes the dress rehearsal (the Philharmonic’s dress rehearsals were open to a limited audience), arguing that there is no other way to explain the presence of Brahms and Dvořák on stage during a performance. Eduard Hanslick

, a music critic in Vienna at this time, reported: “The Rhapsody was respectfully but not warmly received. I had expected it to make a livelier effect after the impression of the dress rehearsal.” Even though audience reception at the actual concert may have been less than enthusiastic, Richter saw promise in Dvořák’s work and asked him to write a symphony for the orchestra. He finished the symphony the following year, in October 1880, and traveled to Vienna to play the composition on the piano for Richter, who was very excited about the work.

Dvořák expected to have the Vienna Philharmonic premier his symphony in December 1880. However, Richter postponed the performance repeatedly, citing family sickness and an over-worked orchestra. Dvořák, suspicious of anti-Czech feelings in Vienna, eventually grew frustrated. He learned later that members of the orchestra objected to performing works by the relatively new Czech composer in two consecutive seasons.

Dvořák expected to have the Vienna Philharmonic premier his symphony in December 1880. However, Richter postponed the performance repeatedly, citing family sickness and an over-worked orchestra. Dvořák, suspicious of anti-Czech feelings in Vienna, eventually grew frustrated. He learned later that members of the orchestra objected to performing works by the relatively new Czech composer in two consecutive seasons.

Instead, Adolf Čech conducted the premier of Dvořák’s sixth symphony with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra

on March 25, 1881, in Prague

. Richter did eventually conduct the piece in London

in 1882. Though he never conducted it in Vienna, he still retained an interest in Dvořák’s compositions. The Vienna Philharmonic did not perform this symphony until 1942.

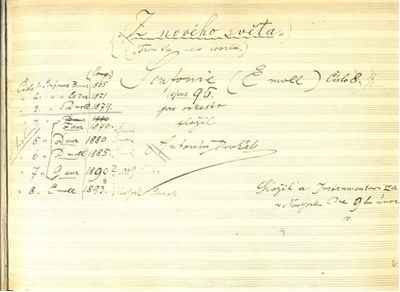

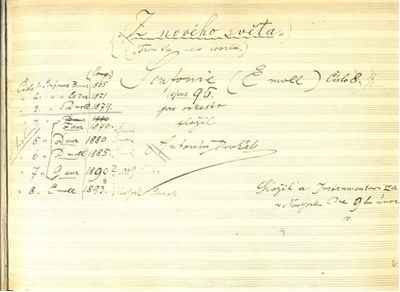

Dvořák’s Symphony no. 6 was originally issued as his Symphony no. 1 by Simrock

Dvořák’s Symphony no. 6 was originally issued as his Symphony no. 1 by Simrock

, Dvořák’s German music publisher, as it was his first published work in this genre. Further confusion in numbering Dvořák’s symphonies came from several sources. Dvořák believed that his first symphony was lost, and numbered the remaining symphonies no.1 – no.8 by date of composition. Simrock continued to order the symphonies by publication date, ignoring the first four symphonies. Therefore, according to Dvořák, this work was his fifth symphony, according to the publisher it was his first, but chronologically (and after the first symphony was recovered) it is now known as his Symphony no. 6. The order of symphonies was first codified by Dvořák scholar, Otakar Šourek.

Gerald Abraham writes, “….(H)e had recognizable affinities with all three of the principal musical tendencies of the period, with the conservatism of Brahms and his followers, with the modernism of the Liszt-Wagner school, and with the nationalism that was in almost every country…in Europe.” To be sure, he had personal contact with musical giants from each of these traditions. In 1863, Richard Wagner

came to Prague and conducted a program of his own works, in which Dvořák played as a violist. He was very impressed with Wagner’s compositional style. Dvořák then applied for a stipend from Svatobor, a Prague association for the support of artists, to finance a period of study with Liszt in Weimar

. He was not selected for the prize. This turn of events probably greatly affected Dvořák’s eventual shift to a personal integrative style of composition, as opposed to a complete devotion to the Wagner school. In 1874, Dvořák submitted numerous works to apply for the Austrian State Stipendium, money offered to young poor artists by the Ministry of Education. On the panel of judges that awarded Dvořák the prize was Johannes Brahms

, who became a longtime friend and supporter of the young Czech. And in Prague itself was the older and more revered Czech nationalistic composer Smetana

, who eventually supported Dvořák by being among the first to program and conduct concerts that included his compositions. David Beveridge states, “In 1880, with the composition of his Sixth Symphony, Dvořák had at last achieved an optimum balance between his nationalistic-romantic proclivities and the demands of classical form.”

Yet, it may not be quite so simple to categorically say that a mix or balance of these influences culminated in the Sixth Symphony. According to David Brodbeck, Dvořák purposely utilized sources from the German tradition in order to cater to a Viennese audience and their cultural values. At that time, Viennese culture elevated German qualities, and not Czech. In keeping with this attitude, Dvořák referenced works by Brahms and Beethoven, as well as a Viennese dance.

The symphony is written in four movements

:

Instrumentation

2 flutes (piccolo

), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns

, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba

, timpani

, strings

.

The piccolo is only used in the third movement. The trombones and tuba are only used in the first and fourth movements.

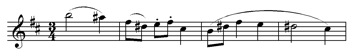

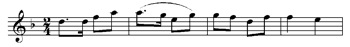

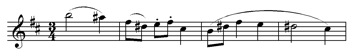

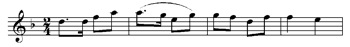

. It is in 3/4 time and in the key of D major. Dvořák has included extra melodic material with two primary themes, two transitional phrases, and two secondary themes. The initial primary theme has three parts that Dvořák uses in many ways throughout the piece. The first (x), is an ascending fourth, followed by a repeated D with a dotted rhythm (y), and finally descending stepwise motion from the fifth scale degree to the second (z).

The transition begins in measure 78 with an upward stepwise motive that could be seen as filling in the interval of a fourth, which opened the initial primary theme (x), or as an inversion of the downward stepwise motive that closes the same primary theme (z). Either way, a connection can be drawn back to the initial primary theme.

The transition begins in measure 78 with an upward stepwise motive that could be seen as filling in the interval of a fourth, which opened the initial primary theme (x), or as an inversion of the downward stepwise motive that closes the same primary theme (z). Either way, a connection can be drawn back to the initial primary theme.

The secondary area begins in measure 108. The initial secondary theme is in B minor and includes rhythmic similarities to the initial primary theme (y and z). In measure 120 the second secondary theme enters in B major. It is a lyrical theme presented in the oboe. This section begins pianissimo and gradually crescendos into the closing section in measure 161, which is also in B major.

The score includes a repeat of the exposition

The score includes a repeat of the exposition

; however, this is not usually observed because Dvořák later decided to eliminate it. “He finally wrote in the score now owned by the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra: ‘once and for all without repetition.’”

The development begins with the thematic elements of the first primary theme, using each of these fragments in turn, as well as material from the second transitional phrase. It begins very softly and gradually gathers excitement with an increase in orchestration, fugato sections, and circle-of-fifths progressions. Shortly before the recapitulation, the strings break into a homophonic fortissimo statement of rising quarter notes for eleven measures, marked pesante (measures 310-320), before the full orchestra joins in for the retransition into the recapitulation in D major.

The movement ends with a D major coda (measure 480) that reviews the previous themes over pedals emphasizing the dominant and tonic pitches. The same string pesante

section that preceded the recapitulation

returns in measure 512. The piece then builds to a fortissimo with a canon of the first primary theme in the trumpets and trombones that is taken up by the whole orchestra. The excitement decays to pianissimo for what appears to be a peaceful conclusion, until a unison fortissimo statement of the second secondary theme closes the movement.

containing variations within the sections. The form can be described as A B A C A B A. The Adagio is lightly scored with frequent woodwind solos. Otakar Šourek, an early 20th century Dvořák scholar, wrote, “the second movement has the quality of a softly yearning nocturne and of an ardently passionate intermezzo

.” The main theme, or A section, is built on the interval of an upward fourth, just as the first movement begins (x). Much of the movement is focused on this theme, which returns many times and is varied throughout. Each A section is in B major.

The B sections feature a short falling motive and also incorporate material from the introduction of the movement, measures 1-4. The first B section (measures 35-72) moves to D major and is preceded by a modulatory transition. When the B section returns in measure 150 it remains in B major so the transition is not needed.

The B sections feature a short falling motive and also incorporate material from the introduction of the movement, measures 1-4. The first B section (measures 35-72) moves to D major and is preceded by a modulatory transition. When the B section returns in measure 150 it remains in B major so the transition is not needed.

The C section, measures 104-139, could be considered developmental. It begins in B minor but moves away fairly quickly and is tonally unstable. It uses melodic material from the introduction as well as the main theme. In measures 115-122, the first four notes of the main theme are presented at half the speed, first at the original pitches, and then a major third higher. This material is then returned to the original rhythmic values and passed back and forth between the horn and oboe.

The Adagio closes with a simplified version of the opening of the main theme, which reveals the close relationship between the introductory material and the main theme. The movement ends with pianissimo woodwinds and overlapping motives, similar to the opening of the movement.

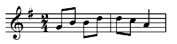

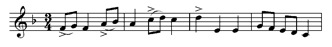

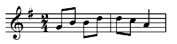

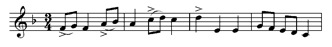

. This is a quick dance in triple meter with hemiolas at the beginning of the phrase. The effect is that the movement appears to alternate between 2/4 and 3/4. The use of a Furiant is a nationalistic feature.

The form of the third movement is a ternary

The form of the third movement is a ternary

scherzo

and trio. It is in D minor, moving to D major in the trio (measures 154-288). The opening scherzo has two sections which are both repeated. The melody is characterized by frequent hemiolas and a half-step interval in the first section. The second section is more lyrical and is in F major. The trio is much more relaxed and retains the triple meter feel throughout, with less hemiola interruption. The piccolo is featured in this section, with a lyrical solo over pizzicato strings. The trio winds down with a long D major harmony and the scherzo is ushered in with string section hemiolas. The closing scherzo is almost identical to the opening scherzo, but without repeats.

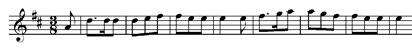

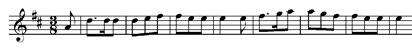

The secondary theme appears in measure 70 in the dominant, A major, and comprises a descending triplet figure. The development section (measures 139-318) reverses the order of themes, first exploring the secondary theme and then the primary theme, frequently with imitation. The recapitulation is fairly straightforward. The piece concludes with a fiery coda

The secondary theme appears in measure 70 in the dominant, A major, and comprises a descending triplet figure. The development section (measures 139-318) reverses the order of themes, first exploring the secondary theme and then the primary theme, frequently with imitation. The recapitulation is fairly straightforward. The piece concludes with a fiery coda

that restates the themes, with several homophonic passages that feature the brass and present the primary theme at half the speed. The symphony closes solidly with a tutti fortissimo statement.

The most common connection claimed is with Johannes Brahms’ Symphony no. 2

, which was written in 1877, three years before Dvořák’s Symphony no. 6. A. Peter Brown writes, “Brahms’s Symphony no. 2, in the same key, was more than an inspiration to Dvořák; it became a model for the younger composer: the first and final movements of both works have the same scoring, tempo, meter, and key…” He points out similarities in the primary themes of the first and fourth movements, as well as structural and orchestration similarities. David Beveridge also compares the first and fourth movements of Dvořák’s Symphony no. 6 with Brahms’ Symphony no. 2, noting that both composers relate their fourth movement primary theme back to the primary theme of the first movement, a cyclical feature.

Writing for Dvořák’s 100th anniversary, Julius Harrison agrees with these comparisons to Brahms’ Symphony no. 2, while also pointing out differences in the two composers:

Robert Layton argues that Dvořák’s early sketches for the first movement were in D minor and 2/4 meter, differing from Brahms’ Symphony No. 2. He cites a Czech folk song, Já mám koně, as the inspiration for the primary theme of the first movement, with Dvořák later altering the mode and time signature. “It is of course the test of his genius that he should have transformed this idea into the glowing and radiant theme that the definitive score can boast.”

There is another possible source for this same primary theme. David Brodbeck writes, “Dvořák’s main theme alludes directly to the so-called Großvater-Tanz

There is another possible source for this same primary theme. David Brodbeck writes, “Dvořák’s main theme alludes directly to the so-called Großvater-Tanz

, which traditionally served as the closing dance at Viennese balls." If this is the case, it would lend support to the idea that Dvořák wrote the symphony specifically for a Vienna audience and lessen the case for Dvořák’s nationalistic influences.

Nors Josephson proposes similarities in form, key structure, and orchestration of the first movement of Dvořák’s Symphony No. 6 with Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3

Nors Josephson proposes similarities in form, key structure, and orchestration of the first movement of Dvořák’s Symphony No. 6 with Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3

. He compares many of Dvořák’s themes with passages by Beethoven, as well as similar compositional techniques. “Aside from the Czech folk-song, Já mám koně, nearly all the principal motifs of Dvořák’s sixth Symphony can be traced back to … compositions by Beethoven and Brahms.” Many of Josephson’s comparisons involve transitional material, modulatory processes, and orchestration, emphasizing that Dvořák was influenced by Beethoven’s procedures, not just his melodies. “Dvořák frequently employed Beethovenian techniques as creative stimuli.”

The second movement of Dvořák’s Symphony No. 6 has often been compared to the third movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9

for its melodic shape, use of woodwinds, and the key structure (B major to D major).

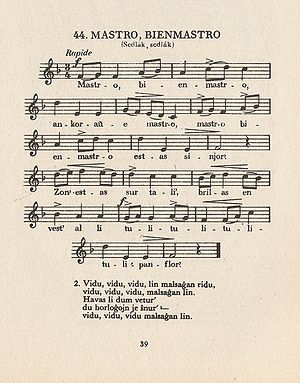

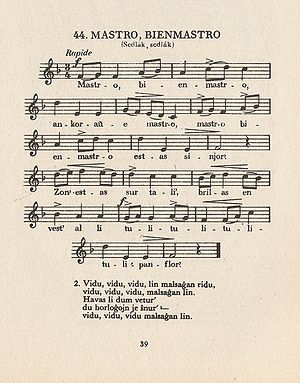

Another Czech folksong, Sedlák, sedlák, may have been used by Dvořák in the third movement of his Symphony No. 6 to create the Furiant melody. John Clapham states that, “the classic model for all true furiants is the folksong ‘Sedlák, sedlák,’ well known to all Czechs.” Dvořák’s theme is not a literal translation of the folksong, but it does have similarities including hemiola in the first half of the phrase and neighbor tone relationships.

Another Czech folksong, Sedlák, sedlák, may have been used by Dvořák in the third movement of his Symphony No. 6 to create the Furiant melody. John Clapham states that, “the classic model for all true furiants is the folksong ‘Sedlák, sedlák,’ well known to all Czechs.” Dvořák’s theme is not a literal translation of the folksong, but it does have similarities including hemiola in the first half of the phrase and neighbor tone relationships.

These examples show that there were many inspirations for Dvořák’s Symphony no. 6. The myriad of possible references and models by Brahms, Beethoven, and Czech folksongs demonstrate Dvořák’s synthesis of his nationalistic style with the Viennese symphonic tradition.

These examples show that there were many inspirations for Dvořák’s Symphony no. 6. The myriad of possible references and models by Brahms, Beethoven, and Czech folksongs demonstrate Dvořák’s synthesis of his nationalistic style with the Viennese symphonic tradition.

In Vienna in 1879 (a year before the intended premiere of the sixth symphony), a political shift was happening. The newly elected Austrian parliament allowed regions to conduct education and official government business in the predominant language of each region, thus posing a seeming threat to the German language and German cultural dominance in general.

While a few years earlier Dvořák might have been judged an acculturated German, in 1879 he was increasingly considered a Czech and thus a threat to the established dominant German culture in Vienna. His previous works, such as the Moravian Duets

, Slavonic Dances

and Slavonic Rhapsody were popular in many other countries in Europe at least in part for their “exoticism

.” But the climate in Vienna was becoming quite unwelcoming of any compositions that issued from non-Germanic roots, especially those works with obvious references to other nationalities (such as the Furiant in Symphony no. 6.) “….(I)n Vienna the musical exoticism that had played so well elsewhere ran head-on into the political crisis engendered by the Liberals’ recent loss of power.” It is likely that this was the main reason that the established, elite Vienna Philharmonic did not premiere Dvořák’s Symphony No. 6. It was first performed in Vienna in 1883 by the Gesellschaft der Musik freunde

, with Wilhelm Gericke

conducting.

Europe outside of Austria

The piece was well liked by audiences and critics in much of Europe. “Not long after Simrock published the D major Symphony, performances were taking place in half a dozen different countries, and generally the new work was so well received as to contribute greatly towards establishing Dvořák as one of the foremost composers of his generation.”

English music critic Ebenezer Prout

described the symphony in his 1882 review as “(a) work that, notwithstanding some imperfections, must be considered one of the most important of its kind produced for some time. Its performance was characterized by immense spirit, and the audience was unreserved in its token of appreciation.” Dvořák’s Symphony no. 6 was especially popular in England. Dvořák traveled to London in 1884 to conduct a program including his Symphony No. 6 with the Royal Philharmonic Society

. His trip was a success and the Royal Philharmonic Society made Dvořák an honorary member a few months later, also commissioning another symphony from him. Joseph Bennett

, writing a review of Dvořák’s works for a London musical publication in 1884, had this to say of him: “Dvořák’s success in England affords matter for much congratulation. We have from him that which is new and not mischievous…that which is founded…upon the natural expression of a people’s musical nature. The more of Dvořák the better, therefore, and the indications are that a good deal of him awaits us.

At Home

At Home

The success Dvořák experienced abroad was recognized in his homeland. In 1878 he led a concert consisting entirely of his own works in Prague, which was very well received. While Dvořák was occasionally criticized for not being nationalistic enough by his own countrymen, in April, 1881, a critic for Dalibor, a Czech paper, wrote: “This new Dvořák symphony simply excels over all others of the same type within contemporary musical literature….In truth, the work (Symphony no. 6) has an imminently Czech nature, just as Dvořák continues along the basis of his great and fluent power, the tree of which is decorated by the ever more beautiful fruits of his creation.”

March 25, 1881. Prague

: Czech Philharmonic Orchestra

, Adolf Čech conductor.

First performance with Hans Richter

:

May 15, 1882. London

: Hans Richter conductor.

North American Premiere:

January 6, 1883. New York

: Philharmonic Society

, Theodore Thomas conductor.

First performance in Vienna:

February 18, 1883. Gesellschaft der Musik freunde

, Wilhelm Gericke

conductor.

First performance by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

:

1942. Vienna

: Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Antonín Dvorák

Antonín Leopold Dvořák was a Czech composer of late Romantic music, who employed the idioms of the folk music of Moravia and his native Bohemia. Dvořák’s own style is sometimes called "romantic-classicist synthesis". His works include symphonic, choral and chamber music, concerti, operas and many...

(1841-1904) composed his Symphony No. 6 in D major, Op. 60, B. 112, in 1880. It is dedicated to Hans Richter

Hans Richter (conductor)

Hans Richter was an Austrian orchestral and operatic conductor.-Biography:Richter was born in Raab , Kingdom of Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Empire. His mother was opera-singer Jozsefa Csazenszky. He studied at the Vienna Conservatory...

, who was the conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

The Vienna Philharmonic is an orchestra in Austria, regularly considered one of the finest in the world....

. With a performance time of approximately 40 minutes, the four-movement piece was one of the first of Dvořák’s large symphonic works to draw international attention. In it, he manages to capture a bit of the Czech national style within a standard Germanic classical-romantic form.

Background

Dvořák’s Symphony No. 6 was composed for the Vienna Philharmonic. In order to understand the context in which he composed this symphonySymphony

A symphony is an extended musical composition in Western classical music, scored almost always for orchestra. A symphony usually contains at least one movement or episode composed according to the sonata principle...

, the climate and reception of Dvořák’s earlier works in Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

should be taken into consideration.

In late 1879, Hans Richter

Hans Richter (conductor)

Hans Richter was an Austrian orchestral and operatic conductor.-Biography:Richter was born in Raab , Kingdom of Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Empire. His mother was opera-singer Jozsefa Csazenszky. He studied at the Vienna Conservatory...

conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in a subscription concert that included the Third Slavonic Rhapsody. According to Dvořák, in a letter dated 23 November, 1879,

I set out last Friday and was present at the performance of my Third Rhapsody, which was liked very much, and I had to show myself to the audience. I sat next to Brahms by the organ in the orchestra, and Richter drew me out. I had to appear. I must tell you that I immediately won the sympathy of the whole orchestra and that out of all the new works they tried over, and Richter said there were sixty of them, they liked my Rhapsody best of all. Richter kissed me on the spot and told me he was very glad to know me.…

Music historians

Musicology

Musicology is the scholarly study of music. The word is used in narrow, broad and intermediate senses. In the narrow sense, musicology is confined to the music history of Western culture...

have made various conclusions regarding what this letter implies about Dvořák’s reception in Vienna. Dvořák scholar John Clapham interprets this letter to say that the audience at the concert responded with a warm ovation, and that Richter was pleased with the work. Yet, according to David Brodbeck, this account probably only describes the dress rehearsal (the Philharmonic’s dress rehearsals were open to a limited audience), arguing that there is no other way to explain the presence of Brahms and Dvořák on stage during a performance. Eduard Hanslick

Eduard Hanslick

Eduard Hanslick was a Bohemian-Austrian music critic.-Biography:Hanslick was born in Prague, the son of Joseph Adolph Hanslick, a bibliographer and music teacher from a German-speaking family, and one of his piano pupils, the daughter of a Jewish merchant from Vienna...

, a music critic in Vienna at this time, reported: “The Rhapsody was respectfully but not warmly received. I had expected it to make a livelier effect after the impression of the dress rehearsal.” Even though audience reception at the actual concert may have been less than enthusiastic, Richter saw promise in Dvořák’s work and asked him to write a symphony for the orchestra. He finished the symphony the following year, in October 1880, and traveled to Vienna to play the composition on the piano for Richter, who was very excited about the work.

Instead, Adolf Čech conducted the premier of Dvořák’s sixth symphony with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra

Czech Philharmonic Orchestra

The Česká filharmonie is a symphony orchestra based in Prague and is the best-known and most respected orchestra in the Czech Republic.- History :...

on March 25, 1881, in Prague

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

. Richter did eventually conduct the piece in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

in 1882. Though he never conducted it in Vienna, he still retained an interest in Dvořák’s compositions. The Vienna Philharmonic did not perform this symphony until 1942.

Fritz Simrock

Friedrich August Simrock, better known as Fritz Simrock was a German music publisher who inherited a publishing firm from his grandfather Nicolaus Simrock...

, Dvořák’s German music publisher, as it was his first published work in this genre. Further confusion in numbering Dvořák’s symphonies came from several sources. Dvořák believed that his first symphony was lost, and numbered the remaining symphonies no.1 – no.8 by date of composition. Simrock continued to order the symphonies by publication date, ignoring the first four symphonies. Therefore, according to Dvořák, this work was his fifth symphony, according to the publisher it was his first, but chronologically (and after the first symphony was recovered) it is now known as his Symphony no. 6. The order of symphonies was first codified by Dvořák scholar, Otakar Šourek.

Compositional Context and Influences

The period of Dvořák’s life that culminated with his Symphony no. 6 in D major was a time of experimentation and development of his personal compositional style. He developed his basic compositional voice largely from a study of the Germanic classical tradition. There are differing opinions about what influences were in play as he wrote his sixth symphony; it is possible to see the Sixth as a synthesis of many influences, or as the focus of just a few.Gerald Abraham writes, “….(H)e had recognizable affinities with all three of the principal musical tendencies of the period, with the conservatism of Brahms and his followers, with the modernism of the Liszt-Wagner school, and with the nationalism that was in almost every country…in Europe.” To be sure, he had personal contact with musical giants from each of these traditions. In 1863, Richard Wagner

Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner was a German composer, conductor, theatre director, philosopher, music theorist, poet, essayist and writer primarily known for his operas...

came to Prague and conducted a program of his own works, in which Dvořák played as a violist. He was very impressed with Wagner’s compositional style. Dvořák then applied for a stipend from Svatobor, a Prague association for the support of artists, to finance a period of study with Liszt in Weimar

Weimar

Weimar is a city in Germany famous for its cultural heritage. It is located in the federal state of Thuringia , north of the Thüringer Wald, east of Erfurt, and southwest of Halle and Leipzig. Its current population is approximately 65,000. The oldest record of the city dates from the year 899...

. He was not selected for the prize. This turn of events probably greatly affected Dvořák’s eventual shift to a personal integrative style of composition, as opposed to a complete devotion to the Wagner school. In 1874, Dvořák submitted numerous works to apply for the Austrian State Stipendium, money offered to young poor artists by the Ministry of Education. On the panel of judges that awarded Dvořák the prize was Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms was a German composer and pianist, and one of the leading musicians of the Romantic period. Born in Hamburg, Brahms spent much of his professional life in Vienna, Austria, where he was a leader of the musical scene...

, who became a longtime friend and supporter of the young Czech. And in Prague itself was the older and more revered Czech nationalistic composer Smetana

Smetana

Smetana is a Slavic loanword in English for a dairy product that is produced by souring heavy cream. Smetana is from Central and Eastern Europe, sometimes perceived to be specifically of Russian origin. It is a soured cream product like crème fraîche , but nowadays mainly sold with 15% to 30%...

, who eventually supported Dvořák by being among the first to program and conduct concerts that included his compositions. David Beveridge states, “In 1880, with the composition of his Sixth Symphony, Dvořák had at last achieved an optimum balance between his nationalistic-romantic proclivities and the demands of classical form.”

Yet, it may not be quite so simple to categorically say that a mix or balance of these influences culminated in the Sixth Symphony. According to David Brodbeck, Dvořák purposely utilized sources from the German tradition in order to cater to a Viennese audience and their cultural values. At that time, Viennese culture elevated German qualities, and not Czech. In keeping with this attitude, Dvořák referenced works by Brahms and Beethoven, as well as a Viennese dance.

Instrumentation and Score

ScoreThe symphony is written in four movements

Movement (music)

A movement is a self-contained part of a musical composition or musical form. While individual or selected movements from a composition are sometimes performed separately, a performance of the complete work requires all the movements to be performed in succession...

:

- Allegro non tantoTempoIn musical terminology, tempo is the speed or pace of a given piece. Tempo is a crucial element of any musical composition, as it can affect the mood and difficulty of a piece.-Measuring tempo:...

- AdagioTempoIn musical terminology, tempo is the speed or pace of a given piece. Tempo is a crucial element of any musical composition, as it can affect the mood and difficulty of a piece.-Measuring tempo:...

- ScherzoScherzoA scherzo is a piece of music, often a movement from a larger piece such as a symphony or a sonata. The scherzo's precise definition has varied over the years, but it often refers to a movement which replaces the minuet as the third movement in a four-movement work, such as a symphony, sonata, or...

(FuriantFuriantA Furiant is a rapid and fiery Bohemian dance in 2/4 and 3/4 time, with frequently shifting accents.The stylised form of the dance was often used by Czech composers such as Antonin Dvořák in the eighth dance from his Slavonic Dances and in his 6th Symphony, and by Bedřich Smetana in The Bartered...

), PrestoTempoIn musical terminology, tempo is the speed or pace of a given piece. Tempo is a crucial element of any musical composition, as it can affect the mood and difficulty of a piece.-Measuring tempo:... - Finale, Allegro con spiritoTempoIn musical terminology, tempo is the speed or pace of a given piece. Tempo is a crucial element of any musical composition, as it can affect the mood and difficulty of a piece.-Measuring tempo:...

Instrumentation

2 flutes (piccolo

Piccolo

The piccolo is a half-size flute, and a member of the woodwind family of musical instruments. The piccolo has the same fingerings as its larger sibling, the standard transverse flute, but the sound it produces is an octave higher than written...

), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns

Horn (instrument)

The horn is a brass instrument consisting of about of tubing wrapped into a coil with a flared bell. A musician who plays the horn is called a horn player ....

, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba

Tuba

The tuba is the largest and lowest-pitched brass instrument. Sound is produced by vibrating or "buzzing" the lips into a large cupped mouthpiece. It is one of the most recent additions to the modern symphony orchestra, first appearing in the mid-19th century, when it largely replaced the...

, timpani

Timpani

Timpani, or kettledrums, are musical instruments in the percussion family. A type of drum, they consist of a skin called a head stretched over a large bowl traditionally made of copper. They are played by striking the head with a specialized drum stick called a timpani stick or timpani mallet...

, strings

String instrument

A string instrument is a musical instrument that produces sound by means of vibrating strings. In the Hornbostel-Sachs scheme of musical instrument classification, used in organology, they are called chordophones...

.

The piccolo is only used in the third movement. The trombones and tuba are only used in the first and fourth movements.

Orchestration and Style

Dvořák’s melodies are beautiful and often presented in the woodwinds and horns, as well as the strings. Dvořák frequently converses back and forth between groups of instruments, sometimes finishing one another’s phrases. The brass are used more as support in tutti passages, only occasionally leading the melody.I. Allegro non tanto

The first movement is written in a traditional sonata formSonata form

Sonata form is a large-scale musical structure used widely since the middle of the 18th century . While it is typically used in the first movement of multi-movement pieces, it is sometimes used in subsequent movements as well—particularly the final movement...

. It is in 3/4 time and in the key of D major. Dvořák has included extra melodic material with two primary themes, two transitional phrases, and two secondary themes. The initial primary theme has three parts that Dvořák uses in many ways throughout the piece. The first (x), is an ascending fourth, followed by a repeated D with a dotted rhythm (y), and finally descending stepwise motion from the fifth scale degree to the second (z).

The secondary area begins in measure 108. The initial secondary theme is in B minor and includes rhythmic similarities to the initial primary theme (y and z). In measure 120 the second secondary theme enters in B major. It is a lyrical theme presented in the oboe. This section begins pianissimo and gradually crescendos into the closing section in measure 161, which is also in B major.

Exposition (music)

In musical form and analysis, exposition is the initial presentation of the thematic material of a musical composition, movement, or section. The use of the term generally implies that the material will be developed or varied....

; however, this is not usually observed because Dvořák later decided to eliminate it. “He finally wrote in the score now owned by the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra: ‘once and for all without repetition.’”

The development begins with the thematic elements of the first primary theme, using each of these fragments in turn, as well as material from the second transitional phrase. It begins very softly and gradually gathers excitement with an increase in orchestration, fugato sections, and circle-of-fifths progressions. Shortly before the recapitulation, the strings break into a homophonic fortissimo statement of rising quarter notes for eleven measures, marked pesante (measures 310-320), before the full orchestra joins in for the retransition into the recapitulation in D major.

The movement ends with a D major coda (measure 480) that reviews the previous themes over pedals emphasizing the dominant and tonic pitches. The same string pesante

Pesante

Pesante is a musical term, meaning "heavy and ponderous." It is often used in Latin languages, such as Spanish or Portuguese, with the word pesado meaning heavy in both of these languages. The French equivalent is lourd....

section that preceded the recapitulation

Recapitulation (music)

In music theory, the recapitulation is one of the sections of a movement written in sonata form. The recapitulation occurs after the movement's development section, and typically presents once more the musical themes from the movement's exposition...

returns in measure 512. The piece then builds to a fortissimo with a canon of the first primary theme in the trumpets and trombones that is taken up by the whole orchestra. The excitement decays to pianissimo for what appears to be a peaceful conclusion, until a unison fortissimo statement of the second secondary theme closes the movement.

II. Adagio

The Adagio, in B major, is a loose rondoRondo

Rondo, and its French equivalent rondeau, is a word that has been used in music in a number of ways, most often in reference to a musical form, but also to a character-type that is distinct from the form...

containing variations within the sections. The form can be described as A B A C A B A. The Adagio is lightly scored with frequent woodwind solos. Otakar Šourek, an early 20th century Dvořák scholar, wrote, “the second movement has the quality of a softly yearning nocturne and of an ardently passionate intermezzo

Intermezzo

In music, an intermezzo , in the most general sense, is a composition which fits between other musical or dramatic entities, such as acts of a play or movements of a larger musical work...

.” The main theme, or A section, is built on the interval of an upward fourth, just as the first movement begins (x). Much of the movement is focused on this theme, which returns many times and is varied throughout. Each A section is in B major.

The C section, measures 104-139, could be considered developmental. It begins in B minor but moves away fairly quickly and is tonally unstable. It uses melodic material from the introduction as well as the main theme. In measures 115-122, the first four notes of the main theme are presented at half the speed, first at the original pitches, and then a major third higher. This material is then returned to the original rhythmic values and passed back and forth between the horn and oboe.

The Adagio closes with a simplified version of the opening of the main theme, which reveals the close relationship between the introductory material and the main theme. The movement ends with pianissimo woodwinds and overlapping motives, similar to the opening of the movement.

III. Scherzo (Furiant), Presto

The third movement incorporates a Czech dance, the FuriantFuriant

A Furiant is a rapid and fiery Bohemian dance in 2/4 and 3/4 time, with frequently shifting accents.The stylised form of the dance was often used by Czech composers such as Antonin Dvořák in the eighth dance from his Slavonic Dances and in his 6th Symphony, and by Bedřich Smetana in The Bartered...

. This is a quick dance in triple meter with hemiolas at the beginning of the phrase. The effect is that the movement appears to alternate between 2/4 and 3/4. The use of a Furiant is a nationalistic feature.

Ternary form

Ternary form, sometimes called song form, is a three-part musical form, usually schematicized as A-B-A. The first and third parts are musically identical, or very nearly so, while the second part in some way provides a contrast with them...

scherzo

Scherzo

A scherzo is a piece of music, often a movement from a larger piece such as a symphony or a sonata. The scherzo's precise definition has varied over the years, but it often refers to a movement which replaces the minuet as the third movement in a four-movement work, such as a symphony, sonata, or...

and trio. It is in D minor, moving to D major in the trio (measures 154-288). The opening scherzo has two sections which are both repeated. The melody is characterized by frequent hemiolas and a half-step interval in the first section. The second section is more lyrical and is in F major. The trio is much more relaxed and retains the triple meter feel throughout, with less hemiola interruption. The piccolo is featured in this section, with a lyrical solo over pizzicato strings. The trio winds down with a long D major harmony and the scherzo is ushered in with string section hemiolas. The closing scherzo is almost identical to the opening scherzo, but without repeats.

IV. Finale, Allegro con spirito

The Finale is in sonata form and follows the conventions of structure and harmonic motion. The exposition begins in D major with a primary theme that resembles the first primary theme of the first movement, including an upward interval of a fourth (x), a dotted rhythm on a repeated D (y), and stepwise motion.

Coda (music)

Coda is a term used in music in a number of different senses, primarily to designate a passage that brings a piece to an end. Technically, it is an expanded cadence...

that restates the themes, with several homophonic passages that feature the brass and present the primary theme at half the speed. The symphony closes solidly with a tutti fortissimo statement.

Influences

Dvořák’s Symphony No. 6 has many similarities to symphonies by Brahms and Beethoven, as well as references to Czech folk tunes. These links have been proposed and debated by scholars and music critics.The most common connection claimed is with Johannes Brahms’ Symphony no. 2

Symphony No. 2 (Brahms)

The Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73, was composed by Johannes Brahms in the summer of 1877 during a visit to Pörtschach am Wörthersee, a town in the Austrian province of Carinthia. Its composition was brief in comparison with the fifteen years it took Brahms to complete his First Symphony...

, which was written in 1877, three years before Dvořák’s Symphony no. 6. A. Peter Brown writes, “Brahms’s Symphony no. 2, in the same key, was more than an inspiration to Dvořák; it became a model for the younger composer: the first and final movements of both works have the same scoring, tempo, meter, and key…” He points out similarities in the primary themes of the first and fourth movements, as well as structural and orchestration similarities. David Beveridge also compares the first and fourth movements of Dvořák’s Symphony no. 6 with Brahms’ Symphony no. 2, noting that both composers relate their fourth movement primary theme back to the primary theme of the first movement, a cyclical feature.

Writing for Dvořák’s 100th anniversary, Julius Harrison agrees with these comparisons to Brahms’ Symphony no. 2, while also pointing out differences in the two composers:

Brahms takes a D major triad as a kind of thesis in triplicate, from which, by means of the melodies resulting from that triad, he proceeds step by step to a logical conclusion. Dvořák takes an odd bit of sound, a mere dominant-tonic progression … and then, to our great delight fashions it into a movement, structurally classical, yet thematically having the nature of lovely improvisation.

Robert Layton argues that Dvořák’s early sketches for the first movement were in D minor and 2/4 meter, differing from Brahms’ Symphony No. 2. He cites a Czech folk song, Já mám koně, as the inspiration for the primary theme of the first movement, with Dvořák later altering the mode and time signature. “It is of course the test of his genius that he should have transformed this idea into the glowing and radiant theme that the definitive score can boast.”

Grossvater Tanz

The Grossvater Tanz is a German dance tune from the 17th century. It is generally considered a traditional folk tune...

, which traditionally served as the closing dance at Viennese balls." If this is the case, it would lend support to the idea that Dvořák wrote the symphony specifically for a Vienna audience and lessen the case for Dvořák’s nationalistic influences.

Symphony No. 3 (Beethoven)

Ludwig van Beethoven's Symphony No. 3 in E flat major , also known as the Eroica , is a landmark musical work marking the full arrival of the composer's "middle-period," a series of unprecedented large scale works of emotional depth and structural rigor.The symphony is widely regarded as a mature...

. He compares many of Dvořák’s themes with passages by Beethoven, as well as similar compositional techniques. “Aside from the Czech folk-song, Já mám koně, nearly all the principal motifs of Dvořák’s sixth Symphony can be traced back to … compositions by Beethoven and Brahms.” Many of Josephson’s comparisons involve transitional material, modulatory processes, and orchestration, emphasizing that Dvořák was influenced by Beethoven’s procedures, not just his melodies. “Dvořák frequently employed Beethovenian techniques as creative stimuli.”

The second movement of Dvořák’s Symphony No. 6 has often been compared to the third movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9

Symphony No. 9 (Beethoven)

The Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, is the final complete symphony of Ludwig van Beethoven. Completed in 1824, the symphony is one of the best known works of the Western classical repertoire, and has been adapted for use as the European Anthem...

for its melodic shape, use of woodwinds, and the key structure (B major to D major).

Critical and Cultural Reception

ViennaIn Vienna in 1879 (a year before the intended premiere of the sixth symphony), a political shift was happening. The newly elected Austrian parliament allowed regions to conduct education and official government business in the predominant language of each region, thus posing a seeming threat to the German language and German cultural dominance in general.

While a few years earlier Dvořák might have been judged an acculturated German, in 1879 he was increasingly considered a Czech and thus a threat to the established dominant German culture in Vienna. His previous works, such as the Moravian Duets

Moravian Duets

Moravian Duets by Antonín Dvořák is a cycle of 23 Moravian folk poetry settings for two voices with piano accompaniment, composed between 1875 and 1881. The Duets, published in three volumes, Op. 20 , Op. 32 , and Op. 38 , occupy an important position among Dvořák's other works. The fifteen duets...

, Slavonic Dances

Slavonic Dances

The Slavonic Dances are a series of 16 orchestral pieces composed by Antonín Dvořák in 1878 and 1886 and published in two sets as Opus 46 and Opus 72 respectively. Originally written for piano four hands, the Slavonic Dances were inspired by Johannes Brahms's own Hungarian Dances and were...

and Slavonic Rhapsody were popular in many other countries in Europe at least in part for their “exoticism

Exoticism

Exoticism is a trend in art and design, influenced by some ethnic groups or civilizations since the late 19th-century. In music exoticism is a genre in which the rhythms, melodies, or instrumentation are designed to evoke the atmosphere of far-off lands or ancient times Exoticism (from 'exotic')...

.” But the climate in Vienna was becoming quite unwelcoming of any compositions that issued from non-Germanic roots, especially those works with obvious references to other nationalities (such as the Furiant in Symphony no. 6.) “….(I)n Vienna the musical exoticism that had played so well elsewhere ran head-on into the political crisis engendered by the Liberals’ recent loss of power.” It is likely that this was the main reason that the established, elite Vienna Philharmonic did not premiere Dvořák’s Symphony No. 6. It was first performed in Vienna in 1883 by the Gesellschaft der Musik freunde

Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

The Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien , was founded in 1812 by Joseph von Sonnleithner, general secretary of the Court Theatre, Vienna, Austria. Its official charter, drafted in 1814, states that the purpose of the Society was to promote music in all its facets...

, with Wilhelm Gericke

Wilhelm Gericke

Wilhelm Gericke was an Austrian-born conductor and composer who worked in Vienna and Boston.-Biography:...

conducting.

Europe outside of Austria

The piece was well liked by audiences and critics in much of Europe. “Not long after Simrock published the D major Symphony, performances were taking place in half a dozen different countries, and generally the new work was so well received as to contribute greatly towards establishing Dvořák as one of the foremost composers of his generation.”

English music critic Ebenezer Prout

Ebenezer Prout

Ebenezer Prout , was an English musical theorist, writer, teacher and composer, whose instruction, afterwards embodied in a series of standard works, underpinned the work of many British musicians of succeeding generations....

described the symphony in his 1882 review as “(a) work that, notwithstanding some imperfections, must be considered one of the most important of its kind produced for some time. Its performance was characterized by immense spirit, and the audience was unreserved in its token of appreciation.” Dvořák’s Symphony no. 6 was especially popular in England. Dvořák traveled to London in 1884 to conduct a program including his Symphony No. 6 with the Royal Philharmonic Society

Royal Philharmonic Society

The Royal Philharmonic Society is a British music society, formed in 1813. It was originally formed in London to promote performances of instrumental music there. Many distinguished composers and performers have taken part in its concerts...

. His trip was a success and the Royal Philharmonic Society made Dvořák an honorary member a few months later, also commissioning another symphony from him. Joseph Bennett

Joseph Bennett (critic)

Joseph Bennett was an English music critic and librettist. After an early career as a schoolmaster and organist, he was engaged as a music critic by The Sunday Times in 1865...

, writing a review of Dvořák’s works for a London musical publication in 1884, had this to say of him: “Dvořák’s success in England affords matter for much congratulation. We have from him that which is new and not mischievous…that which is founded…upon the natural expression of a people’s musical nature. The more of Dvořák the better, therefore, and the indications are that a good deal of him awaits us.

The success Dvořák experienced abroad was recognized in his homeland. In 1878 he led a concert consisting entirely of his own works in Prague, which was very well received. While Dvořák was occasionally criticized for not being nationalistic enough by his own countrymen, in April, 1881, a critic for Dalibor, a Czech paper, wrote: “This new Dvořák symphony simply excels over all others of the same type within contemporary musical literature….In truth, the work (Symphony no. 6) has an imminently Czech nature, just as Dvořák continues along the basis of his great and fluent power, the tree of which is decorated by the ever more beautiful fruits of his creation.”

Performance history

Premiere:March 25, 1881. Prague

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

: Czech Philharmonic Orchestra

Czech Philharmonic Orchestra

The Česká filharmonie is a symphony orchestra based in Prague and is the best-known and most respected orchestra in the Czech Republic.- History :...

, Adolf Čech conductor.

First performance with Hans Richter

Hans Richter (conductor)

Hans Richter was an Austrian orchestral and operatic conductor.-Biography:Richter was born in Raab , Kingdom of Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Empire. His mother was opera-singer Jozsefa Csazenszky. He studied at the Vienna Conservatory...

:

May 15, 1882. London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

: Hans Richter conductor.

North American Premiere:

January 6, 1883. New York

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

: Philharmonic Society

New York Philharmonic

The New York Philharmonic is a symphony orchestra based in New York City in the United States. It is one of the American orchestras commonly referred to as the "Big Five"...

, Theodore Thomas conductor.

First performance in Vienna:

February 18, 1883. Gesellschaft der Musik freunde

Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

The Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien , was founded in 1812 by Joseph von Sonnleithner, general secretary of the Court Theatre, Vienna, Austria. Its official charter, drafted in 1814, states that the purpose of the Society was to promote music in all its facets...

, Wilhelm Gericke

Wilhelm Gericke

Wilhelm Gericke was an Austrian-born conductor and composer who worked in Vienna and Boston.-Biography:...

conductor.

First performance by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

The Vienna Philharmonic is an orchestra in Austria, regularly considered one of the finest in the world....

:

1942. Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

: Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Selective Discography

| Year | Orchestra | Conductor | Record Label |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra The Slovenská filharmónia is a symphony orchestra in Bratislava, Slovakia.Founded in 1949, the orchestra has resided since the 1950s in the Baroque era Reduta Bratislava concert hall constructed in 1773... |

Zdeněk Košler Zdenek Košler Zdeněk Košler was a Czech conductor, who played an important role in Czech musical life of the second half of 20th century, notably during the sixties and the eighties. He was particularly well-known as an opera conductor.... |

Opus Opus (record label) OPUS is a former Czechoslovakia major state-owned record label and music publishing house based in Bratislava, now a label, Opus a.s., of Slovakia.... , MHS |

| (Live) 2002 | Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Czech Philharmonic Orchestra The Česká filharmonie is a symphony orchestra based in Prague and is the best-known and most respected orchestra in the Czech Republic.- History :... |

Charles Mackerras Charles Mackerras Sir Alan Charles Maclaurin Mackerras, AC, CH, CBE was an Australian conductor. He was an authority on the operas of Janáček and Mozart, and the comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan... |

Supraphon Supraphon Supraphon Music Publishing is a Czech record label, it is oriented mainly towards publishing classical music, with an emphasis on Czech and Slovak composers.- History :... |

| 1999 | Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra The Vienna Philharmonic is an orchestra in Austria, regularly considered one of the finest in the world.... |

Myung-whun Chung Myung-Whun Chung Myung-whun Chung is a South Korean pianist and conductor.His sisters, violinist Kyung-wha Chung, and cellist Myung-wha Chung, and he at one time performed together as the Chung Trio. He was a joined second-prize winner in the 1974 International Tchaikovsky Competition. Chung studied conducting at... |

Deutsche Grammophon Deutsche Grammophon Deutsche Grammophon is a German classical record label which was the foundation of the future corporation to be known as PolyGram. It is now part of Universal Music Group since its acquisition and absorption of PolyGram in 1999, and it is also UMG's oldest active label... |

| 1992 | Czech Philharmonic Orchestra | Jiří Bělohlávek Jirí Belohlávek Jiří Bělohlávek is a Czech conductor. His father was a barrister and judge. In his youth Bělohlávek studied cello with Miloš Sádlo and was later a graduate of the Prague Conservatory and the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague... |

Chandos Chandos Records Chandos Records is an independent classical music recording company based in Colchester, Essex, in the United Kingdom, founded in 1979 by Brian Couzens.- Background :... |

| 1991 | Cleveland Orchestra Cleveland Orchestra The Cleveland Orchestra is an American orchestra based in Cleveland, Ohio. It is one of the five American orchestras informally referred to as the "Big Five". Founded in 1918, the orchestra plays most of its concerts at Severance Hall... |

Christoph von Dohnányi Christoph von Dohnányi Christoph von Dohnányi is a German conductor of Hungarian ancestry.- Youth and World War II :Dohnányi was born in Berlin, Germany to jurist Hans von Dohnányi and Christine Bonhoeffer. His uncle on his mother's side was Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a Lutheran pastor and theologian/ethicist... |

Decca Decca Records Decca Records began as a British record label established in 1929 by Edward Lewis. Its U.S. label was established in late 1934; however, owing to World War II, the link with the British company was broken for several decades.... |

| 1988 | Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra The Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra is an orchestra based in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Its primary performing venue is the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts... |

Zdeněk Mácal Zdenek Mácal Zdeněk Mácal is a Czech conductor.Mácal began violin lessons with his father at age four. He later attended the Brno Conservatory and the Janáček Academy of Music and Performing Arts, where he graduated in 1960 with top honors. He became principal conductor of the Prague Symphony Orchestra and... |

Koss, Classics |

| 1987 | Czech Philharmonic Orchestra | Libor Pešek Libor Pešek Libor Pešek KBE is a Czech conductor.Pešek was born in Prague and studied conducting, piano, cello and trombone at the Academy of Musical Arts there, with Václav Smetáček and Karel Ančerl among his teachers. He worked at the Pilsen and Prague Operas, and from 1958 to 1964 was the founder and... |

Virgin Virgin Records Virgin Records is a British record label founded by English entrepreneur Richard Branson, Simon Draper, and Nik Powell in 1972. The company grew to be a worldwide music phenomenon, with platinum performers such as Roy Orbison, Devo, Genesis, Keith Richards, Janet Jackson, Culture Club, Lenny... , Classics |

| 1986 | Scottish National Orchestra | Neeme Järvi Neeme Järvi Neeme Järvi is an Estonian-born conductor.-Early life:Järvi studied music first in Tallinn, and later in Leningrad at the Leningrad Conservatory under Yevgeny Mravinsky, and Nikolai Rabinovich, among others... |

Chandos |

| (Live) 1984 | Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra | Yuri Ahronovich Yuri Ahronovich Yuri Mikhaylovich Ahronovitch was a Soviet-born Israeli conductor.Born in Leningrad, he studied music and the violin from the age of 4. In 1954 he graduated as conductor from the Leningrad Conservatory. He studied with Nathan Rachlin and Kurt Sanderling... |

BIS BIS Records BIS Records is a record label founded in 1973 by Robert von Bahr. It is located in Åkersberga, Sweden.BIS focuses on classical music, both contemporary and early, especially works that are not already well represented by existing recordings.... |

| 1981 | Philharmonia Orchestra Philharmonia Orchestra The Philharmonia Orchestra is one of the leading orchestras in Great Britain, based in London. Since 1995, it has been based in the Royal Festival Hall. In Britain it is also the resident orchestra at De Montfort Hall, Leicester and the Corn Exchange, Bedford, as well as The Anvil, Basingstoke... |

Sir Andrew Davis Andrew Davis (conductor) Sir Andrew Frank Davis CBE is a British conductor.Born in Ashridge, Hertfordshire to Robert J. Davis and his wife Florence J. née Badminton, Davis grew up in Chesham, Buckinghamshire, and in Watford. Davis attended Watford Boys' Grammar School, where he studied classics in his sixth form years... |

CBS CBS Records CBS Records is a record label founded by CBS Corporation in 2006 to take advantage of music from its entertainment properties owned by CBS Television Studios. The initial label roster consisted of only three artists; rock band Señor Happy and singer/songwriters Will Dailey and P.J... |

| 1980 | London Philharmonic Orchestra London Philharmonic Orchestra The London Philharmonic Orchestra , based in London, is one of the major orchestras of the United Kingdom, and is based in the Royal Festival Hall. In addition, the LPO is the main resident orchestra of the Glyndebourne Festival Opera... |

Mstislav Rostropovich Mstislav Rostropovich Mstislav Leopoldovich Rostropovich, KBE , known to close friends as Slava, was a Soviet and Russian cellist and conductor. He was married to the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya. He is widely considered to have been the greatest cellist of the second half of the 20th century, and one of the greatest of... |

Angel Angel Records Angel Records is a record label belonging to EMI. It was formed in 1953 and specialised in classical music, but included an occasional operetta or Broadway score... |

| c. 1980 | Prague Symphony Orchestra Prague Symphony Orchestra The Prague Symphony Orchestra was founded in 1934 by Rudolf Pekárek. In the 1930s the orchestra performed the scores for many Czech films, and also appeared regularly on Czech radio. An early promoter of the orchestra was Dr... |

Václav Smetáček Václav Smetácek Václav Smetáček was a Czech conductor, composer, and oboist.He studied in Prague among others with Jaroslav Křička, conducting with Metod Doležil and Pavel Dědeček, musicology, aesthetics, and philosophy at Charles University... |

Panton Panton Records Panton Records or PANTON was a Czechoslovakian and later Czech record label and music publishing house of the Czech Music Fund, founded in 1968.In Czechoslovakia it was one of the three major state-owned labels, the other two being Supraphon and Opus.... |

| 1976 | Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Royal Philharmonic Orchestra The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra is a British orchestra based in London. It tours widely, and is sometimes referred to as "Britain's national orchestra"... |

Charles Groves Charles Groves Sir Charles Barnard Groves CBE was an English conductor. He was known for the breadth of his repertoire and for encouraging contemporary composers and young conductors.... |

HMV/EMI EMI The EMI Group, also known as EMI Music or simply EMI, is a multinational music company headquartered in London, United Kingdom. It is the fourth-largest business group and family of record labels in the recording industry and one of the "big four" record companies. EMI Group also has a major... |

| 1972 | Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra The Berlin Philharmonic, German: , formerly Berliner Philharmonisches Orchester , is an orchestra based in Berlin, Germany. In 2006, a group of ten European media outlets voted the Berlin Philharmonic number three on a list of "top ten European Orchestras", after the Vienna Philharmonic and the... |

Rafael Kubelik Rafael Kubelík Rafael Jeroným Kubelík was a Czech conductor and composer.-Early life:Kubelík was born in Býchory, Bohemia, Austria-Hungary, today's Czech Republic. He was the sixth child of the Bohemian violinist Jan Kubelík, whom the younger Kubelík described as "a kind of god to me." His mother was a Hungarian... |

DGG |

| 1968 | Boston Symphony Orchestra Boston Symphony Orchestra The Boston Symphony Orchestra is an orchestra based in Boston, Massachusetts. It is one of the five American orchestras commonly referred to as the "Big Five". Founded in 1881, the BSO plays most of its concerts at Boston's Symphony Hall and in the summer performs at the Tanglewood Music Center... |

Erich Leinsdorf Erich Leinsdorf Erich Leinsdorf was a naturalized American Austrian conductor. He performed and recorded with leading orchestras and opera companies throughout the United States and Europe, earning a reputation for exacting standards as well as an acerbic personality... |

RCA RCA Records RCA Records is one of the flagship labels of Sony Music Entertainment. The RCA initials stand for Radio Corporation of America , which was the parent corporation from 1929 to 1985 and a partner from 1985 to 1986.RCA's Canadian unit is Sony's oldest label... |

| 1967 | London Symphony Orchestra London Symphony Orchestra The London Symphony Orchestra is a major orchestra of the United Kingdom, as well as one of the best-known orchestras in the world. Since 1982, the LSO has been based in London's Barbican Centre.-History:... |

Witold Rowicki Witold Rowicki Witold Rowicki was a Polish conductor. He held principal conducting positions with the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra and the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra.His recordings include:... |

Philips Philips Records Philips Records is a record label that was founded by Dutch electronics company Philips. It was started by "Philips Phonographische Industrie" in 1950. Recordings were made with popular artists of various nationalities and also with classical artists from Germany, France and Holland. Philips also... |

| 1966 | Czech Philharmonic Orchestra | Karel Ančerl Karel Ancerl Karel Ančerl , was a Czech conductor, known for his performances of contemporary music and for his interpretations of music by Czech composers... |

Supraphon, Artia |

| 1965 | London Symphony Orchestra | István Kertész | London London Records London Records, referred to as London Recordings in logo, is a record label headquartered in the United Kingdom, originally marketing records in the United States, Canada and Latin America from 1947 to 1979, then becoming a semi-independent label.... |

| 1960 | Czech Philharmonic Orchestra | Karel Šejna Karel Šejna Karel Šejna was a Czech double bassist and conductor, the principal conductor of the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra in 1950.-Life and career:... |

Supraphon, Artia |

| 1950 | Cleveland Orchestra | Erich Leinsdorf | Columbia Columbia Records Columbia Records is an American record label, owned by Japan's Sony Music Entertainment, operating under the Columbia Music Group with Aware Records. It was founded in 1888, evolving from an earlier enterprise, the American Graphophone Company — successor to the Volta Graphophone Company... |

| 1938 | Czech Philharmonic Orchestra | Václav Talich Václav Talich Václav Talich was a Czech conductor, violinist and pedagogue.- Life :Born in Kroměříž, Moravia, he started his musical career in a student orchestra in Klatovy. From 1897 to 1903 he studied at the conservatory in Prague with Otakar Ševčík... |

Supraphon, Koch Koch Records E1 Music , the primary subsidiary of E1 Entertainment LP, is the largest independent record label in the United States. It is also distributed by the Universal Music Group in Europe under the name E1 Universal... |