The Penelopiad

Encyclopedia

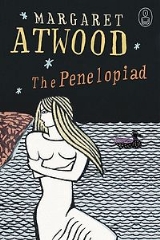

The Penelopiad is a novella

by Margaret Atwood

. It was published in 2005 as part of the first set of books in the Canongate Myth Series

where contemporary authors rewrite ancient myths

. In The Penelopiad, Penelope

reminisces on the events during the Odyssey

, life in Hades

, Odysseus

, Helen, and her relationships with her parents. A chorus

of the twelve maids, whom Odysseus believed were disloyal and whom Telemachus

hanged, interrupt Penelope's narrative to express their view on events. The maids' interludes use a new genre each time, including a jump-rope rhyme

, a lament

, an idyll

, a ballad

, a lecture, a court trial and several types of songs.

The novella's central themes include the effects of story-telling perspectives, double standards between the genders and the classes, and the fairness of justice. Atwood had previously used characters and storylines from Greek mythology in fiction such as her novel The Robber Bride

, short story The Elysium Lifestyle Mansions and poems "Circe: Mud Poems" and "Helen of Troy Does Counter Dancing" but used Robert Graves

’ The Greek Myths

and E. V. Rieu

and D. C. H. Rieu

's version of the Odyssey to prepare for this novella.

The book was translated into 28 languages and released simultaneously around the world by 33 publishers. In the Canadian market, it peaked on the best seller lists at number one in MacLean's

and number two in The Globe and Mail

, but did not place on the New York Times Best Seller List

in the American market. Some critics found the writing to be typical of Atwood, even amongst her finest work, while others found some aspects, like the chorus of maids, disagreeable. A theatrical version was co-produced by the Canadian National Arts Centre

and the British Royal Shakespeare Company

. The play was performed at the Swan Theatre

in Stratford-upon-Avon

and the National Arts Centre in Ottawa

during the summer and fall of 2007 by an all-female cast led by director Josette Bushell-Mingo

. In the winter season 2011/2012, the show will be given its professional Toronto premiere by Nightwood Theatre, with an all-female cast led by director Kelly Thornton.

solicited author Margaret Atwood

to write a novella re-telling a classic myth of her choice. Byng explained it would be published simultaneously in several languages as part of an international project called the Canongate Myth Series

. Atwood agreed to help the rising young publisher by participating in the project. From her home in Toronto

, the 64-year-old author made attempts at writing the Norse creation myth

and a Native American story but struggled. After speaking with her British literary agent about canceling her contract, Atwood began thinking about the Odyssey

. She had first read it as a teenager and remembered finding the imagery of Penelope’s twelve maids being hanged in the denouement disturbing. Atwood believed the roles of Penelope and her maids during Odysseus' absence had been a largely neglected scholarly topic and that she could help address it with this project.

The novella recaps Penelope

The novella recaps Penelope

’s life in hindsight from 21st century Hades; she recalls her family life in Sparta

, her marriage to Odysseus

, her dealing with suitors during his absence, and the aftermath of Odysseus' return. The relationship with her parents was challenging: her father

became overly affectionate after attempting to murder her, and her mother

was absent-minded and negligent. At fifteen, Penelope married Odysseus, who had rigged the contest that decided which suitor would marry her. Penelope was happy with him, even though he was mocked behind his back by Helen and some maids for his short stature and lesser developed home, Ithaca

. The couple broke with tradition by moving to the husband’s kingdom. In Ithaca, neither Odysseus’ mother Anticleia, nor his nurse Eurycleia, liked Penelope but eventually Eurycleia helped Penelope settle into her new role and became friendly, but often patronising. Shortly after the birth of their son, Telemachus

, Odysseus was called to war, leaving Penelope to run the kingdom and raise Telemachus alone. News of the war and rumours of Odysseus’ journey back sporadically reached Ithaca and with the growing possibility that Odysseus was not returning an increasing number of suitors moved in to court Penelope. Convinced the suitors were more interested in controlling her kingdom than loving her, she stalled them. The suitors pressured her by consuming and wasting much of the kingdom's resources. She feared violence if she outright denied their offer of marriage so she announced she would make her decision on which to marry once she finished her father-in-law’s shroud. She enlisted twelve maids to help her unravel the shroud at night and spy on the suitors. Odysseus eventually returned but in disguise. Penelope recognised him immediately and instructed her maids not to reveal his identity. After the suitors were massacred, Odysseus instructed Telemachus to execute the maids who he believed were in league with them. Twelve were hanged while Penelope slept. Afterwards, Penelope and Odysseus told each other stories of their time apart, but on the issue of the maids Penelope remained silent to avoid the appearance of sympathy for those already judged and condemned as traitors.

During her narrative, Penelope expresses opinions on several people, addresses historical misconceptions, and comments on life in Hades. She is most critical of Helen whom Penelope blames for ruining her life. Penelope identifies Odysseus’ specialty as making people look like fools and wonders why his stories have survived so long, despite being an admitted liar. She dispels the rumour that she slept with Amphinomus

and the rumour that she slept with all the suitors and consequently gave birth to Pan.

Between chapters in which Penelope is narrating, the twelve maids speak on topics from their point-of-view. They lament their childhood as slaves with no parents or playtime, sing of freedom, and dream of being princesses. They contrast their lives to Telemachus’ and wonder if they would have killed him as a child if they knew he would kill them as a young man. They blame Penelope and Eurycleia for allowing them to unjustly die. In Hades, they haunt both Penelope and Odysseus.

and ending in a 17-line iambic dimeter poem. Other narrative styles used by the Chorus include a lament

, a folk song

, an idyll

, a sea shanty

, a ballad

, a drama

, an anthropology lecture

, a court trial

, and a love song

.

Penelope’s story uses simple and deliberately naive prose. The tone is described as casual, wandering, and street-wise with Atwood’s dry humour and characteristic bittersweet and melancholic feminist voice. The book uses the first-person narrative, though Penelope sometimes addresses the reader through the second person pronoun

. One reviewer noted that Penelope is portrayed as "an intelligent woman who knows better than to exhibit her intelligence". Because she contrasts past events as they occurred from her perspective with the elaborations of Odysseus and with what is recorded in myths today, she is described as a metafiction

al narrator.

and Menelaus

to Telemachus, and Odysseus to a Scheria

n court make Odysseus into a hero as he fights monsters and seduces goddesses. According to Penelope in The Penelopiad Odysseus was a liar who drunkenly fought a one-eyed bartender then boasted it was a giant cannibalistic cyclops

. Homer portrays Penelope as loyal, patient, and the ideal wife, as he contrasts her to Clytemnestra

who killed Agamemnon

upon his return from Troy. In The Penelopiad, Penelope feels compelled to tell her story because she is unsatisfied with Homer's portrayal of her and the other myths about her sleeping with the suitors and giving birth to Pan. She rejects the role of the ideal wife and admits she was just trying to survive. The Odyssey makes the maids into traitors who consort with the suitors. From the maids' perspective, they were innocent victims, used by Penelope to spy, raped and abused by the suitors, and then murdered by Odysseus and Telemachus. Atwood shows the truth occupies a third position between the myths and the biased points of view.

, and Iris and Laura in The Blind Assassin

, and follows Atwood's doubt of an amicable universal sisterhood. The story does endorse some feminist reassessments of the Odyssey, like Penelope recognising Odysseus while disguised and that the geese slaughtered by the eagle in Penelope's dream were her maids and not the suitors. Using the maids' lecture on anthropology, Atwood satirises Robert Graves

' theory of a matriarchal lunar cult

in Greek myth. The lecture makes a series of connections, concluding that the rape and execution of the maids by men represent the overthrow of the matriarchal

society in favor of patriarchy

. The lecture ends with lines from anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss

' Elementary Structures of Kinship: "Consider us pure symbol. We're no more real than money."

Double standards amongst genders and classes are exposed throughout the novella. Odysseus commits adultery with Circe while expecting Penelope to remain loyal to him. The maids' relations with the suitors are seen as treasonous and earn them an execution. Penelope condemns Helen for her involvement in getting men killed at Troy. At the same time, Penelope excuses her involvement in getting the maids killed even though, as Atwood reveals, Penelope enlisted the maids to spy on the suitors and even encouraged them to continue after some were raped.

Helen for her erroneously idealised image in the Odyssey as the archetypal female. Penelope acts like a judicial arbiter, a position she held in Ithaca as the head of state and, during Odysseus’ absence, as head of the household. The ancient form of justice and punishment, which was swift and simple due to the lack of courts, prisons, and currency, is tempered by more modern concepts of balanced distributions of social benefits and burdens. Penelope’s chosen form of punishment for Helen is to correct the historical records with her own bias by portraying her as vain and superficial, as someone who measures her worth by the number of men who died fighting for her.

The maids also deliver their version of narrative justice on Odysseus and Telemachus, who ordered and carried out their execution, and on Penelope who was complicit in their killing. The maids do not have the same sanctioned voice as Penelope and are relegated to unauthoritative genres, though their persistence eventually leads to more valued cultural forms. Their testimony, contrasted with Penelope’s excuses while condemning Helen, demonstrates the tendency of judicial processes to not act upon the whole truth. When compared with the historical record, dominated by the stories in the Odyssey, the conclusion, as one academic states, is that the concepts of justice and penalties are established by "who has the power to say who is punished, whose ideas count", and that "justice is underwritten by social inequalities and inequitable power dynamics".

and specifically the work of Northrop Frye

and his Anatomy of Criticism

. According to this literary theory, contemporary works are not independent but are part of an underlying pattern that re-invents and adapts a finite number of timeless concepts and structures of meaning. In The Penelopiad, Atwood re-writes archetypes of female passivity and victimisation while using contemporary ideas of justice and a variety of genres.

The edition of the Odyssey that Atwood read was the E. V. Rieu

and D. C. H. Rieu

's translation. For research she consulted Robert Graves

’ The Greek Myths

. Graves, an adherent to Samuel Butler

's theory that the Odyssey was written by a woman, also wrote The White Goddess

which formed the basis of the Maid's anthropology lecture.

Atwood had previously written using themes and characters from ancient Greek myths. She wrote a short story in Ovid Metamorphosed called The Elysium Lifestyle Mansions re-telling a myth with Apollo

and the immortal prophet the Sibyl

from the perspective of the latter living in the modern age. Her 1993 novel The Robber Bride

roughly parallels the Iliad but is set in Toronto. In that novel the characters Tony and Zenia share the same animosity and competition as Penelope and Helen in The Penelopiad. Her poem "Circe: Mud Poems", published in 1976, casts doubt on Penelope's honourable image:

Atwood published "Helen of Troy Does Counter Dancing" in her 1996 collection Morning in the Burned House in which Helen appears in a contemporary setting as an erotic dancer and justifies her exploitation as men fantasize over her:

, which also included A History of Myth by Karen Armstrong

and a third title chosen by each publisher (most chose Weight by Jeanette Winterson

). The Penelopiad was translated into 28 languages and released simultaneously around the world by 33 publishers, including Canongate Books

in the UK, Knopf

in Canada, Grove/Atlantic Inc.

in the US, and Text Publishing in Australia and New Zealand. The French translation was published in Canada by Éditions du Boréal and in France by Groupe Flammarion

. The trade paperback was released in 2006. Laural Merlington narrated the 3-hour unabridged audiobook which was published by Brilliance Audio and released along side the hardcover. Merlington's narration was positively received, though sometimes upstaged by the unnamed actresses voicing the maids.

and number two in The Globe and Mail

in the fiction category. In the American market the book did not place on the New York Times Best Seller list

but was listed as an "Editors' Choice". The book was nominated for the 2006 Mythopoeic Fantasy Award for Adult Literature

and long-listed for the 2007 International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award

. The book's French translation was nominated at the 2006 Governor General's Literary Awards

for best English to French translation.

Some reviewers like Christopher Tayler and David Flusfeder, both writing for The Daily Telegraph

, praised the book as "enjoyable [and] intelligent" with "Atwood at her finest". Robert Wiersema

echoed that sentiment, adding that the book shows Atwood as "fierce and ambitious, clever and thoughtful". The review in the National Post

called the book "a brilliant tour de force". Specifically singled out as being good are the book's wit, rhythm, structure, and story. Mary Beard

found the book to be "brilliant" except for the chapter entitled "An Anthropology Lecture" which she called "complete rubbish". Others criticised the book as being "merely a riff on a better story that comes dangerously close to being a spoof" and saying it "does not fare well [as a] colloquial feminist retelling". Specifically, the scenes with the chorus of maidservants are said to be "mere outlines of characters" with Elizabeth Hand writing in The Washington Post

that they have "the air of a failed Monty Python

sketch". In the journal English Studies, Odin Dekkers and L. R. Leavis described the book as "a piece of deliberate self-indulgence", that it reads like an "over-the-top W. S. Gilbert

", and they compare it to Wendy Cope

’s limericks reducing T. S. Eliot

's The Waste Land

to five lines.

at St James's Church, Piccadilly

on 26 October 2005, Atwood finished a draft theatrical script. The Canadian National Arts Centre

and the British Royal Shakespeare Company

expressed interest and both agreed to co-produce. Funding was raised mostly from nine Canadian women, dubbed the "Penelope Circle", who each donated CAD$50,000 to the National Arts Centre. An all-female cast was selected consisting of seven Canadian and six British actors, with Josette Bushell-Mingo

directing and Veronica Tennant

as the choreographer. For music a trio, consisting of percussions, keyboard, and cello, were positioned above the stage. They assembled in Stratford-upon-Avon

and rehearsed in June and July 2007. The 100-minute play was staged at the Swan Theatre

between 27 July and 18 August at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa

between 17 September and 6 October. Atwood’s script gave little stage direction allowing Bushell-Mingo to develop the action. Critics in both countries lauded Penny Downie

’s performance as Penelope, but found the play had too much narration of story rather than dramatisation. Adjustments made between productions resulted in the Canadian performance having emotional depth that was lacking in Bushell-Mingo’s direction of the twelve maids. The play subsequently had runs in Vancouver at the Stanley Industrial Alliance Stage

between October 26 and November 20, 2011, and in Toronto at the Nightwood Theatre

between January 10–29, 2012.

Novella

A novella is a written, fictional, prose narrative usually longer than a novelette but shorter than a novel. The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America Nebula Awards for science fiction define the novella as having a word count between 17,500 and 40,000...

by Margaret Atwood

Margaret Atwood

Margaret Eleanor Atwood, is a Canadian poet, novelist, literary critic, essayist, and environmental activist. She is among the most-honoured authors of fiction in recent history; she is a winner of the Arthur C...

. It was published in 2005 as part of the first set of books in the Canongate Myth Series

Canongate Myth Series

Canongate Myth Series is a series of short novels in which ancient myths from myriad cultures are reimagined and rewritten by contemporary authors. The project was conceived in 1999 by Jamie Byng, owner of the independent foundation Scottish publisher Canongate Books, and the first three titles in...

where contemporary authors rewrite ancient myths

Mythology

The term mythology can refer either to the study of myths, or to a body or collection of myths. As examples, comparative mythology is the study of connections between myths from different cultures, whereas Greek mythology is the body of myths from ancient Greece...

. In The Penelopiad, Penelope

Penelope

In Homer's Odyssey, Penelope is the faithful wife of Odysseus, who keeps her suitors at bay in his long absence and is eventually reunited with him....

reminisces on the events during the Odyssey

Odyssey

The Odyssey is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is, in part, a sequel to the Iliad, the other work ascribed to Homer. The poem is fundamental to the modern Western canon, and is the second—the Iliad being the first—extant work of Western literature...

, life in Hades

Hades

Hades , Hadēs, originally , Haidēs or , Aidēs , meaning "the unseen") was the ancient Greek god of the underworld. The genitive , Haidou, was an elision to denote locality: "[the house/dominion] of Hades". Eventually, the nominative came to designate the abode of the dead.In Greek mythology, Hades...

, Odysseus

Odysseus

Odysseus or Ulysses was a legendary Greek king of Ithaca and the hero of Homer's epic poem the Odyssey. Odysseus also plays a key role in Homer's Iliad and other works in the Epic Cycle....

, Helen, and her relationships with her parents. A chorus

Greek chorus

A Greek chorus is a homogenous, non-individualised group of performers in the plays of classical Greece, who comment with a collective voice on the dramatic action....

of the twelve maids, whom Odysseus believed were disloyal and whom Telemachus

Telemachus

Telemachus is a figure in Greek mythology, the son of Odysseus and Penelope, and a central character in Homer's Odyssey. The first four books in particular focus on Telemachus' journeys in search of news about his father, who has been away at war...

hanged, interrupt Penelope's narrative to express their view on events. The maids' interludes use a new genre each time, including a jump-rope rhyme

Jump-rope rhyme

A skipping rhyme , is a rhyme chanted by children while skipping. Such rhymes have been recorded in all cultures where skipping is played. Examples of English-language rhymes have been found going back to at least the 17th century...

, a lament

Lament

A lament or lamentation is a song, poem, or piece of music expressing grief, regret, or mourning.-History:Many of the oldest and most lasting poems in human history have been laments. Laments are present in both the Iliad and the Odyssey, and laments continued to be sung in elegiacs accompanied by...

, an idyll

Idyll

An idyll or idyl is a short poem, descriptive of rustic life, written in the style of Theocritus' short pastoral poems, the Idylls....

, a ballad

Ballad

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads were particularly characteristic of British and Irish popular poetry and song from the later medieval period until the 19th century and used extensively across Europe and later the Americas, Australia and North Africa. Many...

, a lecture, a court trial and several types of songs.

The novella's central themes include the effects of story-telling perspectives, double standards between the genders and the classes, and the fairness of justice. Atwood had previously used characters and storylines from Greek mythology in fiction such as her novel The Robber Bride

The Robber Bride

The Robber Bride is a Margaret Atwood novel first published by McClelland and Stewart in 1993. Set in present-day Toronto, Ontario, the novel begins with three women who meet once a month in a restaurant to share a meal....

, short story The Elysium Lifestyle Mansions and poems "Circe: Mud Poems" and "Helen of Troy Does Counter Dancing" but used Robert Graves

Robert Graves

Robert von Ranke Graves 24 July 1895 – 7 December 1985 was an English poet, translator and novelist. During his long life he produced more than 140 works...

’ The Greek Myths

The Greek Myths

The Greek Myths is a mythography, a compendium of Greek mythology, by the poet and writer Robert Graves, normally published in two volumes....

and E. V. Rieu

E. V. Rieu

Emile Victor Rieu CBE was a classicist, publisher and poet, best known for his lucid translations of Homer, as editor of Penguin Classics, and for a modern translation of the four Gospels which evolved from his role as editor of a projected Penguin translation of the Bible...

and D. C. H. Rieu

D. C. H. Rieu

Dominic Christopher Henry Rieu was a classical scholar and son of the famous E. V. Rieu. After attending Highgate School, he studied English and Classics at Queen's College, Oxford. As part of the West Yorkshire Regiment in 1941, he was injured at Cheren and subsequently awarded the Military Cross...

's version of the Odyssey to prepare for this novella.

The book was translated into 28 languages and released simultaneously around the world by 33 publishers. In the Canadian market, it peaked on the best seller lists at number one in MacLean's

Maclean's

Maclean's is a Canadian weekly news magazine, reporting on Canadian issues such as politics, pop culture, and current events.-History:Founded in 1905 by Toronto journalist/entrepreneur Lt.-Col. John Bayne Maclean, a 43-year-old trade magazine publisher who purchased an advertising agency's in-house...

and number two in The Globe and Mail

The Globe and Mail

The Globe and Mail is a nationally distributed Canadian newspaper, based in Toronto and printed in six cities across the country. With a weekly readership of approximately 1 million, it is Canada's largest-circulation national newspaper and second-largest daily newspaper after the Toronto Star...

, but did not place on the New York Times Best Seller List

New York Times Best Seller list

The New York Times Best Seller list is widely considered the preeminent list of best-selling books in the United States. It is published weekly in The New York Times Book Review magazine, which is published in the Sunday edition of The New York Times and as a stand-alone publication...

in the American market. Some critics found the writing to be typical of Atwood, even amongst her finest work, while others found some aspects, like the chorus of maids, disagreeable. A theatrical version was co-produced by the Canadian National Arts Centre

National Arts Centre

The National Arts Centre is a centre for the performing arts located in Ottawa, Ontario, between Elgin Street and the Rideau Canal...

and the British Royal Shakespeare Company

Royal Shakespeare Company

The Royal Shakespeare Company is a major British theatre company, based in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England. The company employs 700 staff and produces around 20 productions a year from its home in Stratford-upon-Avon and plays regularly in London, Newcastle-upon-Tyne and on tour across...

. The play was performed at the Swan Theatre

Swan Theatre (Stratford)

The Swan Theatre is a theatre belonging to the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-upon-Avon, England. It is built on to the side of the larger Royal Shakespeare Theatre, occupying the Victorian Gothic structure that formerly housed the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre that preceded the RST but was...

in Stratford-upon-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon is a market town and civil parish in south Warwickshire, England. It lies on the River Avon, south east of Birmingham and south west of Warwick. It is the largest and most populous town of the District of Stratford-on-Avon, which uses the term "on" to indicate that it covers...

and the National Arts Centre in Ottawa

Ottawa

Ottawa is the capital of Canada, the second largest city in the Province of Ontario, and the fourth largest city in the country. The city is located on the south bank of the Ottawa River in the eastern portion of Southern Ontario...

during the summer and fall of 2007 by an all-female cast led by director Josette Bushell-Mingo

Josette Bushell-Mingo

Josette Bushell-Mingo is a Swedish-based British theatre actor and director of African descent. She was nominated for a Laurence Olivier Award in 2000 for Best Actress in a Musical for her role as Rafiki in the London production of The Lion King . In 2001, she founded a black-led arts festival...

. In the winter season 2011/2012, the show will be given its professional Toronto premiere by Nightwood Theatre, with an all-female cast led by director Kelly Thornton.

Background

Publisher Jamie Byng of Canongate BooksCanongate Books

Canongate Books is a Scottish independent publishing firm based in Edinburgh; it is named for The Canongate, an area of the city. It is most recognised for publishing the Booker Prizewinner Life of Pi...

solicited author Margaret Atwood

Margaret Atwood

Margaret Eleanor Atwood, is a Canadian poet, novelist, literary critic, essayist, and environmental activist. She is among the most-honoured authors of fiction in recent history; she is a winner of the Arthur C...

to write a novella re-telling a classic myth of her choice. Byng explained it would be published simultaneously in several languages as part of an international project called the Canongate Myth Series

Canongate Myth Series

Canongate Myth Series is a series of short novels in which ancient myths from myriad cultures are reimagined and rewritten by contemporary authors. The project was conceived in 1999 by Jamie Byng, owner of the independent foundation Scottish publisher Canongate Books, and the first three titles in...

. Atwood agreed to help the rising young publisher by participating in the project. From her home in Toronto

Toronto

Toronto is the provincial capital of Ontario and the largest city in Canada. It is located in Southern Ontario on the northwestern shore of Lake Ontario. A relatively modern city, Toronto's history dates back to the late-18th century, when its land was first purchased by the British monarchy from...

, the 64-year-old author made attempts at writing the Norse creation myth

Ask and Embla

In Norse mythology, Ask and Embla —male and female respectively—were the first two humans, created by the gods. The pair are attested in both the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson...

and a Native American story but struggled. After speaking with her British literary agent about canceling her contract, Atwood began thinking about the Odyssey

Odyssey

The Odyssey is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is, in part, a sequel to the Iliad, the other work ascribed to Homer. The poem is fundamental to the modern Western canon, and is the second—the Iliad being the first—extant work of Western literature...

. She had first read it as a teenager and remembered finding the imagery of Penelope’s twelve maids being hanged in the denouement disturbing. Atwood believed the roles of Penelope and her maids during Odysseus' absence had been a largely neglected scholarly topic and that she could help address it with this project.

Plot

Penelope

In Homer's Odyssey, Penelope is the faithful wife of Odysseus, who keeps her suitors at bay in his long absence and is eventually reunited with him....

’s life in hindsight from 21st century Hades; she recalls her family life in Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

, her marriage to Odysseus

Odysseus

Odysseus or Ulysses was a legendary Greek king of Ithaca and the hero of Homer's epic poem the Odyssey. Odysseus also plays a key role in Homer's Iliad and other works in the Epic Cycle....

, her dealing with suitors during his absence, and the aftermath of Odysseus' return. The relationship with her parents was challenging: her father

Icarius

In Greek mythology, there were two people named Icarius or Ikários .-Icarius of Sparta:One Icarius was the son of either Perieres and Gorgophone or of Oebalus and Bateia, brother of Hippocoon and Tyndareus and, through Periboea, father of Penelope, Perileos, Thoas, Damasippus, Imeusimus, Aletes...

became overly affectionate after attempting to murder her, and her mother

Periboea

In Greek mythology, nine people shared the name Periboea .#Periboea was the daughter of either King Cychreus of Salamis or of Alcathous, her mother in the latter case being either Pyrgo or Evaechme, daughter of Megareus. She married Telamon and became and mother of Ajax...

was absent-minded and negligent. At fifteen, Penelope married Odysseus, who had rigged the contest that decided which suitor would marry her. Penelope was happy with him, even though he was mocked behind his back by Helen and some maids for his short stature and lesser developed home, Ithaca

Ithaca

Ithaca or Ithaka is an island located in the Ionian Sea, in Greece, with an area of and a little more than three thousand inhabitants. It is also a separate regional unit of the Ionian Islands region, and the only municipality of the regional unit. It lies off the northeast coast of Kefalonia and...

. The couple broke with tradition by moving to the husband’s kingdom. In Ithaca, neither Odysseus’ mother Anticleia, nor his nurse Eurycleia, liked Penelope but eventually Eurycleia helped Penelope settle into her new role and became friendly, but often patronising. Shortly after the birth of their son, Telemachus

Telemachus

Telemachus is a figure in Greek mythology, the son of Odysseus and Penelope, and a central character in Homer's Odyssey. The first four books in particular focus on Telemachus' journeys in search of news about his father, who has been away at war...

, Odysseus was called to war, leaving Penelope to run the kingdom and raise Telemachus alone. News of the war and rumours of Odysseus’ journey back sporadically reached Ithaca and with the growing possibility that Odysseus was not returning an increasing number of suitors moved in to court Penelope. Convinced the suitors were more interested in controlling her kingdom than loving her, she stalled them. The suitors pressured her by consuming and wasting much of the kingdom's resources. She feared violence if she outright denied their offer of marriage so she announced she would make her decision on which to marry once she finished her father-in-law’s shroud. She enlisted twelve maids to help her unravel the shroud at night and spy on the suitors. Odysseus eventually returned but in disguise. Penelope recognised him immediately and instructed her maids not to reveal his identity. After the suitors were massacred, Odysseus instructed Telemachus to execute the maids who he believed were in league with them. Twelve were hanged while Penelope slept. Afterwards, Penelope and Odysseus told each other stories of their time apart, but on the issue of the maids Penelope remained silent to avoid the appearance of sympathy for those already judged and condemned as traitors.

During her narrative, Penelope expresses opinions on several people, addresses historical misconceptions, and comments on life in Hades. She is most critical of Helen whom Penelope blames for ruining her life. Penelope identifies Odysseus’ specialty as making people look like fools and wonders why his stories have survived so long, despite being an admitted liar. She dispels the rumour that she slept with Amphinomus

Amphinomus

In Greek mythology, Amphinomus, also Amphínomos , was the son of King Nisos and one of the suitors of Penelope that was killed by Telemachus. Amphinomus was considered the best-behaved of the suitors. Despite Odysseus's warning, he was compelled by Athena to stay, as he had been a suitor...

and the rumour that she slept with all the suitors and consequently gave birth to Pan.

Between chapters in which Penelope is narrating, the twelve maids speak on topics from their point-of-view. They lament their childhood as slaves with no parents or playtime, sing of freedom, and dream of being princesses. They contrast their lives to Telemachus’ and wonder if they would have killed him as a child if they knew he would kill them as a young man. They blame Penelope and Eurycleia for allowing them to unjustly die. In Hades, they haunt both Penelope and Odysseus.

Style

The novella is divided into 29 chapters with introduction, notes, and acknowledgments sections. Structured similarly to a classical Greek drama, the storytelling alternates between Penelope's narrative and the choral commentary of the twelve maids. Penelope narrates 18 chapters with the Chorus contributing 11 chapters dispersed throughout the book. The Chorus uses a new narrative style in each of their chapters, beginning with a jump-rope rhymeJump-rope rhyme

A skipping rhyme , is a rhyme chanted by children while skipping. Such rhymes have been recorded in all cultures where skipping is played. Examples of English-language rhymes have been found going back to at least the 17th century...

and ending in a 17-line iambic dimeter poem. Other narrative styles used by the Chorus include a lament

Lament

A lament or lamentation is a song, poem, or piece of music expressing grief, regret, or mourning.-History:Many of the oldest and most lasting poems in human history have been laments. Laments are present in both the Iliad and the Odyssey, and laments continued to be sung in elegiacs accompanied by...

, a folk song

Folk music

Folk music is an English term encompassing both traditional folk music and contemporary folk music. The term originated in the 19th century. Traditional folk music has been defined in several ways: as music transmitted by mouth, as music of the lower classes, and as music with unknown composers....

, an idyll

Idyll

An idyll or idyl is a short poem, descriptive of rustic life, written in the style of Theocritus' short pastoral poems, the Idylls....

, a sea shanty

Sea shanty

A shanty is a type of work song that was once commonly sung to accompany labor on board large merchant sailing vessels. Shanties became ubiquitous in the 19th century era of the wind-driven packet and clipper ships...

, a ballad

Ballad

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads were particularly characteristic of British and Irish popular poetry and song from the later medieval period until the 19th century and used extensively across Europe and later the Americas, Australia and North Africa. Many...

, a drama

Drama

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance. The term comes from a Greek word meaning "action" , which is derived from "to do","to act" . The enactment of drama in theatre, performed by actors on a stage before an audience, presupposes collaborative modes of production and a...

, an anthropology lecture

Lecture

thumb|A lecture on [[linear algebra]] at the [[Helsinki University of Technology]]A lecture is an oral presentation intended to present information or teach people about a particular subject, for example by a university or college teacher. Lectures are used to convey critical information, history,...

, a court trial

Trial (law)

In law, a trial is when parties to a dispute come together to present information in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court...

, and a love song

Love song

A love song is about falling in love and the feelings it brings. Anthologies of love songs often contain a mixture of both of these types of song. A bawdy song is both humorous and saucy, emphasizing the physical pleasure of love rather than the emotional joy...

.

Penelope’s story uses simple and deliberately naive prose. The tone is described as casual, wandering, and street-wise with Atwood’s dry humour and characteristic bittersweet and melancholic feminist voice. The book uses the first-person narrative, though Penelope sometimes addresses the reader through the second person pronoun

Second-person narrative

The second-person narrative is a narrative mode in which the protagonist or another main character is referred to by employment of second-person personal pronouns and other kinds of addressing forms, for example the English second-person pronoun "you"....

. One reviewer noted that Penelope is portrayed as "an intelligent woman who knows better than to exhibit her intelligence". Because she contrasts past events as they occurred from her perspective with the elaborations of Odysseus and with what is recorded in myths today, she is described as a metafiction

Metafiction

Metafiction, also known as Romantic irony in the context of Romantic works of literature, is a type of fiction that self-consciously addresses the devices of fiction, exposing the fictional illusion...

al narrator.

Perspectives

The novella illustrates the differences perspectives can make. The stories told in the Odyssey by NestorNestor (mythology)

In Greek mythology, Nestor of Gerenia was the son of Neleus and Chloris and the King of Pylos. He became king after Heracles killed Neleus and all of Nestor's siblings...

and Menelaus

Menelaus

Menelaus may refer to;*Menelaus, one of the two most known Atrides, a king of Sparta and son of Atreus and Aerope*Menelaus on the Moon, named after Menelaus of Alexandria.*Menelaus , brother of Ptolemy I Soter...

to Telemachus, and Odysseus to a Scheria

Scheria

Scheria –also known as Scherie or Phaeacia– was a geographical region in Greek mythology, first mentioned in Homer's Odyssey as the home of the Phaiakians and the last destination of Odysseus before returning home to Ithaca.-Odysseus meets Nausikaa:In the Odyssey, after Odysseus sails...

n court make Odysseus into a hero as he fights monsters and seduces goddesses. According to Penelope in The Penelopiad Odysseus was a liar who drunkenly fought a one-eyed bartender then boasted it was a giant cannibalistic cyclops

Polyphemus

Polyphemus is the gigantic one-eyed son of Poseidon and Thoosa in Greek mythology, one of the Cyclopes. His name means "much spoken of" or "famous". Polyphemus plays a pivotal role in Homer's Odyssey.-In Homer's Odyssey:...

. Homer portrays Penelope as loyal, patient, and the ideal wife, as he contrasts her to Clytemnestra

Clytemnestra

Clytemnestra or Clytaemnestra , in ancient Greek legend, was the wife of Agamemnon, king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Mycenae or Argos. In the Oresteia by Aeschylus, she was a femme fatale who murdered her husband, Agamemnon – said by Euripides to be her second husband – and the Trojan princess...

who killed Agamemnon

Agamemnon

In Greek mythology, Agamemnon was the son of King Atreus and Queen Aerope of Mycenae, the brother of Menelaus, the husband of Clytemnestra, and the father of Electra and Orestes. Mythical legends make him the king of Mycenae or Argos, thought to be different names for the same area...

upon his return from Troy. In The Penelopiad, Penelope feels compelled to tell her story because she is unsatisfied with Homer's portrayal of her and the other myths about her sleeping with the suitors and giving birth to Pan. She rejects the role of the ideal wife and admits she was just trying to survive. The Odyssey makes the maids into traitors who consort with the suitors. From the maids' perspective, they were innocent victims, used by Penelope to spy, raped and abused by the suitors, and then murdered by Odysseus and Telemachus. Atwood shows the truth occupies a third position between the myths and the biased points of view.

Feminism and double standards

The book has been called "feminist", and more specifically "vintage Atwood-feminist", but Atwood disagrees, saying, "I wouldn't even call it feminist. Every time you write something from the point of view of a woman, people say that it's feminist." The Penelopiads antagonistic relationship between Penelope and Helen is similar to the relationships of women in Atwood's previous novels: Elaine and Cordelia in Cat's EyeCat's Eye (novel)

Cat's Eye is a 1988 novel by Margaret Atwood. In it, controversial painter Elaine Risley vividly reflects on her childhood and teenage years...

, and Iris and Laura in The Blind Assassin

The Blind Assassin

The Blind Assassin is an award-winning, bestselling novel by the Canadian author Margaret Atwood. It was first published by McClelland and Stewart in 2000. Set in Canada, it is narrated from the present day, referring back to events that span the twentieth century.The work was awarded the Man...

, and follows Atwood's doubt of an amicable universal sisterhood. The story does endorse some feminist reassessments of the Odyssey, like Penelope recognising Odysseus while disguised and that the geese slaughtered by the eagle in Penelope's dream were her maids and not the suitors. Using the maids' lecture on anthropology, Atwood satirises Robert Graves

Robert Graves

Robert von Ranke Graves 24 July 1895 – 7 December 1985 was an English poet, translator and novelist. During his long life he produced more than 140 works...

' theory of a matriarchal lunar cult

Goddess worship

Goddess worship may be*the cult of any goddess in polytheistic religions*worship of a Great Goddess on a henotheistic or monotheistic or duotheistic basis**Hindu Shaktism**the neopagan Goddess movement**Wicca**Dianic Wicca...

in Greek myth. The lecture makes a series of connections, concluding that the rape and execution of the maids by men represent the overthrow of the matriarchal

Matriarchy

A matriarchy is a society in which females, especially mothers, have the central roles of political leadership and moral authority. It is also sometimes called a gynocratic or gynocentric society....

society in favor of patriarchy

Patriarchy

Patriarchy is a social system in which the role of the male as the primary authority figure is central to social organization, and where fathers hold authority over women, children, and property. It implies the institutions of male rule and privilege, and entails female subordination...

. The lecture ends with lines from anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss

Claude Lévi-Strauss

Claude Lévi-Strauss was a French anthropologist and ethnologist, and has been called, along with James George Frazer, the "father of modern anthropology"....

' Elementary Structures of Kinship: "Consider us pure symbol. We're no more real than money."

Double standards amongst genders and classes are exposed throughout the novella. Odysseus commits adultery with Circe while expecting Penelope to remain loyal to him. The maids' relations with the suitors are seen as treasonous and earn them an execution. Penelope condemns Helen for her involvement in getting men killed at Troy. At the same time, Penelope excuses her involvement in getting the maids killed even though, as Atwood reveals, Penelope enlisted the maids to spy on the suitors and even encouraged them to continue after some were raped.

Narrative justice

Penelope’s story is an attempt at narrative justice to retributeRetributive justice

Retributive justice is a theory of justice that considers that punishment, if proportionate, is a morally acceptable response to crime, with an eye to the satisfaction and psychological benefits it can bestow to the aggrieved party, its intimates and society....

Helen for her erroneously idealised image in the Odyssey as the archetypal female. Penelope acts like a judicial arbiter, a position she held in Ithaca as the head of state and, during Odysseus’ absence, as head of the household. The ancient form of justice and punishment, which was swift and simple due to the lack of courts, prisons, and currency, is tempered by more modern concepts of balanced distributions of social benefits and burdens. Penelope’s chosen form of punishment for Helen is to correct the historical records with her own bias by portraying her as vain and superficial, as someone who measures her worth by the number of men who died fighting for her.

The maids also deliver their version of narrative justice on Odysseus and Telemachus, who ordered and carried out their execution, and on Penelope who was complicit in their killing. The maids do not have the same sanctioned voice as Penelope and are relegated to unauthoritative genres, though their persistence eventually leads to more valued cultural forms. Their testimony, contrasted with Penelope’s excuses while condemning Helen, demonstrates the tendency of judicial processes to not act upon the whole truth. When compared with the historical record, dominated by the stories in the Odyssey, the conclusion, as one academic states, is that the concepts of justice and penalties are established by "who has the power to say who is punished, whose ideas count", and that "justice is underwritten by social inequalities and inequitable power dynamics".

Influences

Atwood's use of myths follows archetypal literary criticismArchetypal literary criticism

Archetypal literary criticism is a type of critical theory that interprets a text by focusing on recurring myths and archetypes in the narrative, symbols, images, and character types in a literary work...

and specifically the work of Northrop Frye

Northrop Frye

Herman Northrop Frye, was a Canadian literary critic and literary theorist, considered one of the most influential of the 20th century....

and his Anatomy of Criticism

Anatomy of Criticism

Herman Northrop Frye's Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays attempts to formulate an overall view of the scope, theory, principles, and techniques of literary criticism derived exclusively from literature...

. According to this literary theory, contemporary works are not independent but are part of an underlying pattern that re-invents and adapts a finite number of timeless concepts and structures of meaning. In The Penelopiad, Atwood re-writes archetypes of female passivity and victimisation while using contemporary ideas of justice and a variety of genres.

The edition of the Odyssey that Atwood read was the E. V. Rieu

E. V. Rieu

Emile Victor Rieu CBE was a classicist, publisher and poet, best known for his lucid translations of Homer, as editor of Penguin Classics, and for a modern translation of the four Gospels which evolved from his role as editor of a projected Penguin translation of the Bible...

and D. C. H. Rieu

D. C. H. Rieu

Dominic Christopher Henry Rieu was a classical scholar and son of the famous E. V. Rieu. After attending Highgate School, he studied English and Classics at Queen's College, Oxford. As part of the West Yorkshire Regiment in 1941, he was injured at Cheren and subsequently awarded the Military Cross...

's translation. For research she consulted Robert Graves

Robert Graves

Robert von Ranke Graves 24 July 1895 – 7 December 1985 was an English poet, translator and novelist. During his long life he produced more than 140 works...

’ The Greek Myths

The Greek Myths

The Greek Myths is a mythography, a compendium of Greek mythology, by the poet and writer Robert Graves, normally published in two volumes....

. Graves, an adherent to Samuel Butler

Samuel Butler (novelist)

Samuel Butler was an iconoclastic Victorian author who published a variety of works. Two of his most famous pieces are the Utopian satire Erewhon and a semi-autobiographical novel published posthumously, The Way of All Flesh...

's theory that the Odyssey was written by a woman, also wrote The White Goddess

The White Goddess

The White Goddess: a Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth is a book-length essay on the nature of poetic myth-making by author and poet Robert Graves. First published in 1948, based on earlier articles published in Wales magazine, corrected, revised and enlarged editions appeared in 1948, 1952 and 1961...

which formed the basis of the Maid's anthropology lecture.

Atwood had previously written using themes and characters from ancient Greek myths. She wrote a short story in Ovid Metamorphosed called The Elysium Lifestyle Mansions re-telling a myth with Apollo

Apollo

Apollo is one of the most important and complex of the Olympian deities in Greek and Roman mythology...

and the immortal prophet the Sibyl

Cumaean Sibyl

The ageless Cumaean Sibyl was the priestess presiding over the Apollonian oracle at Cumae, a Greek colony located near Naples, Italy.The word sibyl comes from the ancient Greek word sibylla, meaning prophetess. There were many Sibyls in different locations throughout the ancient world...

from the perspective of the latter living in the modern age. Her 1993 novel The Robber Bride

The Robber Bride

The Robber Bride is a Margaret Atwood novel first published by McClelland and Stewart in 1993. Set in present-day Toronto, Ontario, the novel begins with three women who meet once a month in a restaurant to share a meal....

roughly parallels the Iliad but is set in Toronto. In that novel the characters Tony and Zenia share the same animosity and competition as Penelope and Helen in The Penelopiad. Her poem "Circe: Mud Poems", published in 1976, casts doubt on Penelope's honourable image:

- She’s up to something, she’s weaving

- histories, they are never right,

- she has to do them over,

- she is weaving her version[...]

Atwood published "Helen of Troy Does Counter Dancing" in her 1996 collection Morning in the Burned House in which Helen appears in a contemporary setting as an erotic dancer and justifies her exploitation as men fantasize over her:

- You think I’m not a goddess?

- Try me.

- This is a torch song.

- Touch me and you’ll burn.

Publication

The hardcover version of The Penelopiad was published on 21 October 2005 as part of the launch of the Canongate Myth SeriesCanongate Myth Series

Canongate Myth Series is a series of short novels in which ancient myths from myriad cultures are reimagined and rewritten by contemporary authors. The project was conceived in 1999 by Jamie Byng, owner of the independent foundation Scottish publisher Canongate Books, and the first three titles in...

, which also included A History of Myth by Karen Armstrong

Karen Armstrong

Karen Armstrong FRSL , is a British author and commentator who is the author of twelve books on comparative religion. A former Roman Catholic nun, she went from a conservative to a more liberal and mystical faith...

and a third title chosen by each publisher (most chose Weight by Jeanette Winterson

Jeanette Winterson

Jeanette Winterson OBE is a British novelist.-Early years:Winterson was born in Manchester and adopted on 21 January 1960. She was raised in Accrington, Lancashire, by Constance and John William Winterson...

). The Penelopiad was translated into 28 languages and released simultaneously around the world by 33 publishers, including Canongate Books

Canongate Books

Canongate Books is a Scottish independent publishing firm based in Edinburgh; it is named for The Canongate, an area of the city. It is most recognised for publishing the Booker Prizewinner Life of Pi...

in the UK, Knopf

Alfred A. Knopf

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. is a New York publishing house, founded by Alfred A. Knopf, Sr. in 1915. It was acquired by Random House in 1960 and is now part of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group at Random House. The publishing house is known for its borzoi trademark , which was designed by co-founder...

in Canada, Grove/Atlantic Inc.

Grove/Atlantic Inc.

Grove/Atlantic, Inc. is a New York-based independent publishing house that was formed by the merger of Grove Press and Atlantic Monthly Press. Grove/Atlantic's imprints publish literary fiction, nonfiction, poetry, drama, and translations...

in the US, and Text Publishing in Australia and New Zealand. The French translation was published in Canada by Éditions du Boréal and in France by Groupe Flammarion

Groupe Flammarion

Groupe Flammarion is the fourth largest publishing group in France, comprising many units, including its namesake, founded in 1876 by Ernest Flammarion, as well as units in distribution, sales, printing and bookshops . Flammarion became part of the Italian media conglomerate RCS MediaGroup in 2000...

. The trade paperback was released in 2006. Laural Merlington narrated the 3-hour unabridged audiobook which was published by Brilliance Audio and released along side the hardcover. Merlington's narration was positively received, though sometimes upstaged by the unnamed actresses voicing the maids.

Reception

On best seller lists in the Canadian market, the hardcover peaked at number one in MacLean'sMaclean's

Maclean's is a Canadian weekly news magazine, reporting on Canadian issues such as politics, pop culture, and current events.-History:Founded in 1905 by Toronto journalist/entrepreneur Lt.-Col. John Bayne Maclean, a 43-year-old trade magazine publisher who purchased an advertising agency's in-house...

and number two in The Globe and Mail

The Globe and Mail

The Globe and Mail is a nationally distributed Canadian newspaper, based in Toronto and printed in six cities across the country. With a weekly readership of approximately 1 million, it is Canada's largest-circulation national newspaper and second-largest daily newspaper after the Toronto Star...

in the fiction category. In the American market the book did not place on the New York Times Best Seller list

New York Times Best Seller list

The New York Times Best Seller list is widely considered the preeminent list of best-selling books in the United States. It is published weekly in The New York Times Book Review magazine, which is published in the Sunday edition of The New York Times and as a stand-alone publication...

but was listed as an "Editors' Choice". The book was nominated for the 2006 Mythopoeic Fantasy Award for Adult Literature

Mythopoeic Awards

The Mythopoeic Awards for literature and literary studies are given by the Mythopoeic Society to authors of outstanding works in the fields of myth, fantasy, and the scholarly study of these areas; the full criteria and description can be read on the Mythopoeic Society's -Mythopoeic Fantasy...

and long-listed for the 2007 International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award

International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award

The International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award is an international literary award for a work of fiction, jointly sponsored by the city of Dublin, Ireland and the company IMPAC. At €100,000 it is one of the richest literary prizes in the world...

. The book's French translation was nominated at the 2006 Governor General's Literary Awards

Governor General's Award

The Governor General's Awards are a collection of awards presented by the Governor General of Canada, marking distinction in a number of academic, artistic and social fields. The first was conceived in 1937 by Lord Tweedsmuir, a prolific author of fiction and non-fiction who created the Governor...

for best English to French translation.

Some reviewers like Christopher Tayler and David Flusfeder, both writing for The Daily Telegraph

The Daily Telegraph

The Daily Telegraph is a daily morning broadsheet newspaper distributed throughout the United Kingdom and internationally. The newspaper was founded by Arthur B...

, praised the book as "enjoyable [and] intelligent" with "Atwood at her finest". Robert Wiersema

Robert Wiersema

Robert Wiersema is a Canadian writer. Since 2006, he's published two novels, a novella and a non-fiction book about Bruce Springsteen.-Life and career:Wiersema was born in Agassiz, British Columbia, in 1970...

echoed that sentiment, adding that the book shows Atwood as "fierce and ambitious, clever and thoughtful". The review in the National Post

National Post

The National Post is a Canadian English-language national newspaper based in Don Mills, a district of Toronto. The paper is owned by Postmedia Network Inc. and is published Mondays through Saturdays...

called the book "a brilliant tour de force". Specifically singled out as being good are the book's wit, rhythm, structure, and story. Mary Beard

Mary Beard (classicist)

Winifred Mary Beard is Professor of Classics at the University of Cambridge and a fellow of Newnham College. She is the Classics editor of the Times Literary Supplement, and author of the blog "", which appears in The Times as a regular column...

found the book to be "brilliant" except for the chapter entitled "An Anthropology Lecture" which she called "complete rubbish". Others criticised the book as being "merely a riff on a better story that comes dangerously close to being a spoof" and saying it "does not fare well [as a] colloquial feminist retelling". Specifically, the scenes with the chorus of maidservants are said to be "mere outlines of characters" with Elizabeth Hand writing in The Washington Post

The Washington Post

The Washington Post is Washington, D.C.'s largest newspaper and its oldest still-existing paper, founded in 1877. Located in the capital of the United States, The Post has a particular emphasis on national politics. D.C., Maryland, and Virginia editions are printed for daily circulation...

that they have "the air of a failed Monty Python

Monty Python

Monty Python was a British surreal comedy group who created their influential Monty Python's Flying Circus, a British television comedy sketch show that first aired on the BBC on 5 October 1969. Forty-five episodes were made over four series...

sketch". In the journal English Studies, Odin Dekkers and L. R. Leavis described the book as "a piece of deliberate self-indulgence", that it reads like an "over-the-top W. S. Gilbert

W. S. Gilbert

Sir William Schwenck Gilbert was an English dramatist, librettist, poet and illustrator best known for his fourteen comic operas produced in collaboration with the composer Sir Arthur Sullivan, of which the most famous include H.M.S...

", and they compare it to Wendy Cope

Wendy Cope

Wendy Cope, OBE is an award-winning contemporary English poet. She read history at St Hilda's College, Oxford. She now lives in Ely with the poet Lachlan Mackinnon.-Biography:...

’s limericks reducing T. S. Eliot

T. S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns "T. S." Eliot OM was a playwright, literary critic, and arguably the most important English-language poet of the 20th century. Although he was born an American he moved to the United Kingdom in 1914 and was naturalised as a British subject in 1927 at age 39.The poem that made his...

's The Waste Land

The Waste Land

The Waste Land[A] is a 434-line[B] modernist poem by T. S. Eliot published in 1922. It has been called "one of the most important poems of the 20th century." Despite the poem's obscurity—its shifts between satire and prophecy, its abrupt and unannounced changes of speaker, location and time, its...

to five lines.

Theatrical adaptation

Following a successful dramatic reading directed by Phyllida LloydPhyllida Lloyd

Phyllida Lloyd CBE is an English director, best known for her work in theatre and as the director of the most financially successful British film ever released, Mamma Mia!.-Career:...

at St James's Church, Piccadilly

St James's Church, Piccadilly

St James’s Church, Piccadilly is an Anglican church on Piccadilly in the centre of London, UK. It was designed and built by Sir Christopher Wren....

on 26 October 2005, Atwood finished a draft theatrical script. The Canadian National Arts Centre

National Arts Centre

The National Arts Centre is a centre for the performing arts located in Ottawa, Ontario, between Elgin Street and the Rideau Canal...

and the British Royal Shakespeare Company

Royal Shakespeare Company

The Royal Shakespeare Company is a major British theatre company, based in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England. The company employs 700 staff and produces around 20 productions a year from its home in Stratford-upon-Avon and plays regularly in London, Newcastle-upon-Tyne and on tour across...

expressed interest and both agreed to co-produce. Funding was raised mostly from nine Canadian women, dubbed the "Penelope Circle", who each donated CAD$50,000 to the National Arts Centre. An all-female cast was selected consisting of seven Canadian and six British actors, with Josette Bushell-Mingo

Josette Bushell-Mingo

Josette Bushell-Mingo is a Swedish-based British theatre actor and director of African descent. She was nominated for a Laurence Olivier Award in 2000 for Best Actress in a Musical for her role as Rafiki in the London production of The Lion King . In 2001, she founded a black-led arts festival...

directing and Veronica Tennant

Veronica Tennant

Veronica Tennant, CC, FRSC is a Canadian dance and performance film producer and director, and former ballet dancer.She was born in London, England and moved to Canada with her parents and sister in 1955...

as the choreographer. For music a trio, consisting of percussions, keyboard, and cello, were positioned above the stage. They assembled in Stratford-upon-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon is a market town and civil parish in south Warwickshire, England. It lies on the River Avon, south east of Birmingham and south west of Warwick. It is the largest and most populous town of the District of Stratford-on-Avon, which uses the term "on" to indicate that it covers...

and rehearsed in June and July 2007. The 100-minute play was staged at the Swan Theatre

Swan Theatre (Stratford)

The Swan Theatre is a theatre belonging to the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-upon-Avon, England. It is built on to the side of the larger Royal Shakespeare Theatre, occupying the Victorian Gothic structure that formerly housed the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre that preceded the RST but was...

between 27 July and 18 August at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa

Ottawa

Ottawa is the capital of Canada, the second largest city in the Province of Ontario, and the fourth largest city in the country. The city is located on the south bank of the Ottawa River in the eastern portion of Southern Ontario...

between 17 September and 6 October. Atwood’s script gave little stage direction allowing Bushell-Mingo to develop the action. Critics in both countries lauded Penny Downie

Penny Downie

Penny Downie is an Australian actress, noted for her appearances on British television.She began her career in Australia, initially in Brisbane at Twelfth Night Theatre and Brisbane Arts Theatre. She trained at the National Institute of Dramatic Art , Sydney...

’s performance as Penelope, but found the play had too much narration of story rather than dramatisation. Adjustments made between productions resulted in the Canadian performance having emotional depth that was lacking in Bushell-Mingo’s direction of the twelve maids. The play subsequently had runs in Vancouver at the Stanley Industrial Alliance Stage

Stanley Industrial Alliance Stage

The Stanley Industrial Alliance Stage is a landmark theatre at 12th and Granville Street in Vancouver, British Columbia which serves as the main stage for the Arts Club Theatre Company. The Stanley first opened as a movie theatre in December 1930, and showed movies for over sixty years before...

between October 26 and November 20, 2011, and in Toronto at the Nightwood Theatre

Nightwood theatre

Nightwood Theatre is Canada's oldest professional women’s theatre company. Based in Toronto, it was founded in 1979 by Cynthia Grant, Kim Renders, Mary Vingoe and Maureen White....

between January 10–29, 2012.