.gif)

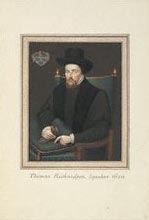

Thomas Richardson (judge)

Encyclopedia

Speaker of the British House of Commons

The Speaker of the House of Commons is the presiding officer of the House of Commons, the United Kingdom's lower chamber of Parliament. The current Speaker is John Bercow, who was elected on 22 June 2009, following the resignation of Michael Martin...

, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas

Chief Justice of the Common Pleas

The Court of Common Pleas, also known as the Common Bench or Common Place, was the second highest common law court in the English legal system until 1880, when it was dissolved. As such, the Chief Justice of the Common Pleas was one of the highest judicial officials in England, behind only the Lord...

and Chief Justice of the King’s Bench

Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales

The Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales is the head of the judiciary and President of the Courts of England and Wales. Historically, he was the second-highest judge of the Courts of England and Wales, after the Lord Chancellor, but that changed as a result of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005,...

.

Origins and early career

The son of William Richardson and Agnes, his wife, he was born at Hardwick, Norfolk, where he was baptised on 3 July 1569. On 5 March 1586-7 he was admitted a student at Lincoln's InnLincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn is one of four Inns of Court in London to which barristers of England and Wales belong and where they are called to the Bar. The other three are Middle Temple, Inner Temple and Gray's Inn. Although Lincoln's Inn is able to trace its official records beyond...

, where he was called to the bar on 28 Jan. 1594-5. In 1605 he was deputy steward to the dean and chapter of Norwich

Anglican Diocese of Norwich

The Diocese of Norwich forms part of the Province of Canterbury in England.It traces its roots in an unbroken line to the diocese of Dunwich founded in 630. In common with many Anglo-Saxon bishoprics it moved, in this case to Elmham in 673...

; afterwards he was recorder, successively, of Bury St. Edmunds

Bury St. Edmunds

Bury St Edmunds is a market town in the county of Suffolk, England, and formerly the county town of West Suffolk. It is the main town in the borough of St Edmundsbury and known for the ruined abbey near the town centre...

and Norwich

Norwich

Norwich is a city in England. It is the regional administrative centre and county town of Norfolk. During the 11th century, Norwich was the largest city in England after London, and one of the most important places in the kingdom...

. He was Lent Reader at Lincoln's Inn

Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn is one of four Inns of Court in London to which barristers of England and Wales belong and where they are called to the Bar. The other three are Middle Temple, Inner Temple and Gray's Inn. Although Lincoln's Inn is able to trace its official records beyond...

in 1614, and on 13 October of the same year was called to the degree of serjeant-at-law

Serjeant-at-law

The Serjeants-at-Law was an order of barristers at the English bar. The position of Serjeant-at-Law , or Sergeant-Counter, was centuries old; there are writs dating to 1300 which identify them as descended from figures in France prior to the Norman Conquest...

; about the same time he was made chancellor to the queen

Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark was queen consort of Scotland, England, and Ireland as the wife of King James VI and I.The second daughter of King Frederick II of Denmark, Anne married James in 1589 at the age of fourteen and bore him three children who survived infancy, including the future Charles I...

.

Speaker of the House of Commons

On the meeting of parliament on 30 January 1620-1, Richardson was chosen speakerSpeaker of the British House of Commons

The Speaker of the House of Commons is the presiding officer of the House of Commons, the United Kingdom's lower chamber of Parliament. The current Speaker is John Bercow, who was elected on 22 June 2009, following the resignation of Michael Martin...

of the House of Commons

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

, in which he sat for St Albans

St Albans (UK Parliament constituency)

St Albans is a parliamentary constituency represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Established in 1885, it is a county constituency in Hertfordshire, and elects one Member of Parliament by the first past the post system of election.From 1554 to 1852 there was a...

. The excuses which he made before accepting this office appear to have been more than formal, for an eye-witness reports that he 'wept downright.' On 25 March 1621 he was knighted at Whitehall

Palace of Whitehall

The Palace of Whitehall was the main residence of the English monarchs in London from 1530 until 1698 when all except Inigo Jones's 1622 Banqueting House was destroyed by fire...

on conveying to the king the congratulations of the commons upon the recent censure of Sir Giles Mompesson

Giles Mompesson

Giles Mompesson was an English malefactor and, officially, "notorious criminal" whose career was one based on speculation and graft. He has come to be regarded as a synonym for graft and official corruption due to his use of nepotism to gain positions of licensing businesses and pocketing the fees...

. In the chair he proved a veritable King Log, and the house had the good sense not to re-elect him. His term of office was marked by the degradation of Bacon

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Albans, KC was an English philosopher, statesman, scientist, lawyer, jurist, author and pioneer of the scientific method. He served both as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England...

.

Judicial advancement

On 20 February 1624-5 he was made king's serjeantSerjeant-at-law

The Serjeants-at-Law was an order of barristers at the English bar. The position of Serjeant-at-Law , or Sergeant-Counter, was centuries old; there are writs dating to 1300 which identify them as descended from figures in France prior to the Norman Conquest...

; and on 28 November 1626 he succeeded Sir Henry Hobart

Sir Henry Hobart, 1st Baronet

Sir Henry Hobart, 1st Baronet SL , of Blickling Hall, was an English judge and politician.The son of Thomas Hobart and Audrey Hare, and Great grandson of Sir James Hobart of Monks Eleigh, Suffolk, who served as Attorney General during the reign of King Henry VII.Sir Henry would further this lineal...

as Chief Justice of the Common Pleas

Chief Justice of the Common Pleas

The Court of Common Pleas, also known as the Common Bench or Common Place, was the second highest common law court in the English legal system until 1880, when it was dissolved. As such, the Chief Justice of the Common Pleas was one of the highest judicial officials in England, behind only the Lord...

, after a vacancy of nearly a year. His advancement was said to have cost him £17,000 and his second marriage (see infra). His opinion, which had the concurrence of his colleagues, 13 November 1628, that the proposed use of the rack to elicit confession from the Duke of Buckingham's

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham KG was the favourite, claimed by some to be the lover, of King James I of England. Despite a very patchy political and military record, he remained at the height of royal favour for the first two years of the reign of Charles I, until he was assassinated...

murderer, Felton

John Felton

John Felton was a lieutenant in the English army who stabbed George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham to death in Portsmouth on 23 August 1628.-Background:...

, was illegal, marks an epoch in the history of our criminal jurisprudence. In the following December he presided at the trial of three of the Jesuits arrested in Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell is an area of central London in the London Borough of Islington. From 1900 to 1965 it was part of the Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury. The well after which it was named was rediscovered in 1924. The watchmaking and watch repairing trades were once of great importance...

, and secured the acquittal of two of them by requiring proof, which was not forthcoming, of their orders.

In the same year he took part in the careful review of the law of constructive treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

occasioned by the case of Hugh Pine, charged with that crime for words spoken derogatory to the king's majesty, the result of which was to limit the offence to cases of imagining the king's death. He also concurred in the guarded and somewhat evasive opinion on the extent of privilege of parliament which the king

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

elicited from the judges on occasion of the turbulent scenes which preceded the dissolution of 4 March 1628-9. By his judgment, imposing a fine of £500 without imprisonment, in the case of Richard Chambers, he went as far as he reasonably could in the direction of leniency; and his concurrence in the barbarous sentences passed upon Alexander Leighton

Alexander Leighton

Alexander Leighton was a Scottish medical doctor and puritan preacher and pamphleteer best known for his 1630 pamphlet that attacked the Anglican church and which led to his torture by King Charles I.-Early life:...

and William Prynne

William Prynne

William Prynne was an English lawyer, author, polemicist, and political figure. He was a prominent Puritan opponent of the church policy of the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud. Although his views on church polity were presbyterian, he became known in the 1640s as an Erastian, arguing for...

was probably dictated by timidity, and contrasts strongly with the tenderness which he exhibited towards the iconoclastic bencher of Lincoln's Inn, Henry Sherfield

Henry Sherfield

Henry Sherfield was an English lawyer, a Member of Parliament for Salisbury in 1623 and 1626. Of Puritan views, he was an iconoclast, and was taken through a celebrated court case.-Life:...

.

Chief Justice of the King’s Bench

Richardson was advanced to the chief-justiceship of the king's benchLord Chief Justice of England and Wales

The Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales is the head of the judiciary and President of the Courts of England and Wales. Historically, he was the second-highest judge of the Courts of England and Wales, after the Lord Chancellor, but that changed as a result of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005,...

on 24 October 1631, and rode the western circuit

Circuit court

Circuit court is the name of court systems in several common law jurisdictions.-History:King Henry II instituted the custom of having judges ride around the countryside each year to hear appeals, rather than forcing everyone to bring their appeals to London...

. Though no puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

, he made, at the instance of the Somerset

Somerset

The ceremonial and non-metropolitan county of Somerset in South West England borders Bristol and Gloucestershire to the north, Wiltshire to the east, Dorset to the south-east, and Devon to the south-west. It is partly bounded to the north and west by the Bristol Channel and the estuary of the...

magistrates in Lent 1632, an order suppressing the 'wakes' or Sunday revels, which were a fertile source of crime in the county, and directed it to be read in church. This brought him into collision with Laud

William Laud

William Laud was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1633 to 1645. One of the High Church Caroline divines, he opposed radical forms of Puritanism...

, who sent for him and told him it was the king's pleasure he should rescind the order. This monition he ignored until it was repeated by the king

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

himself. He then, at the ensuing summer Assizes

Assizes

Assize or Assizes may refer to:Assize or Assizes may refer to:Assize or Assizes may refer to::;in common law countries :::*assizes , an obsolete judicial inquest...

(1633), laid the matter fairly before the justices and grand jury, professing his inability to comply with the royal mandate on the ground that the order had been made by the joint consent of the whole bench, and was in fact a mere confirmation and enlargement of similar orders made in the county since the time of Queen Elizabeth

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

, all which he substantiated from the county records. This caused him to be cited before the council, reprimanded, and transferred to the Essex circuit. 'I am like,' he muttered as he left the council board, 'to be choked with the archbishop's lawn sleeves.' He died at his house in Chancery Lane

Chancery Lane

Chancery Lane is the street which has been the western boundary of the City of London since 1994 having previously been divided between Westminster and Camden...

on 4 February 1634-5. His remains were interred in the north aisle of the choir, Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey

The Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster, popularly known as Westminster Abbey, is a large, mainly Gothic church, in the City of Westminster, London, United Kingdom, located just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is the traditional place of coronation and burial site for English,...

, beneath a marble monument. There is a bust by Hubert Le Sueur

Hubert Le Sueur

Hubert Le Sueur was a French sculptor with the contemporaneous reputation of having trained in Giambologna's Florentine workshop, who assisted Giambologna's foreman, Pietro Tacca, in Paris, finishing and erecting the equestrian statue of Henri IV on the Pont Neuf...

.

Judicial reputation

Richardson was a capable lawyer and a weak man, much addicted to flouts and jeers. 'Let him have the Book of Martyrs he said, when the question whether PrynneWilliam Prynne

William Prynne was an English lawyer, author, polemicist, and political figure. He was a prominent Puritan opponent of the church policy of the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud. Although his views on church polity were presbyterian, he became known in the 1640s as an Erastian, arguing for...

should be allowed the use of books was before the court; 'for the puritans do account him a martyr.' He could also make a caustic jest at his own expense. 'You see now’ he dryly remarked, when by stooping low he had just avoided a missile aimed at him by a condemned felon, 'if I had been an upright judge I had been slain.' He was not without some tincture of polite learning, which caused John Taylor

John Taylor (poet)

John Taylor was an English poet who dubbed himself "The Water Poet".-Biography:He was born in Gloucester, 24 August 1578....

, the water poet, to dedicate to him one of the impressions of his Superbiae Flagellum (1621).

Family and posterity

Richardson married twice. His first wife, Ursula, third daughter of John Southwell of BarhamBarham, Suffolk

Barham is a village and civil parish in the Mid Suffolk district of Suffolk, England. The village is on the River Gipping, near Great Blakenham, Coddenham and Claydon, and is on the A14 road about six miles north of Ipswich. Barham has one pub, The Sorrel Horse....

Hall, Suffolk

Suffolk

Suffolk is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in East Anglia, England. It has borders with Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south. The North Sea lies to the east...

, was buried at St. Andrew's, Holborn

St Andrew, Holborn

St Andrew, Holborn is a Church of England church on the northwestern edge of the City of London, on Holborn within the Ward of Farringdon Without.-Roman and medieval:Roman pottery was found on the site during 2001/02 excavations in the crypt...

, on 13 June 1624. His second wife, married at St Giles in the Fields

St Giles in the Fields

St Giles in the Fields, Holborn, is a church in the London Borough of Camden, in the West End. It is close to the Centre Point office tower and the Tottenham Court Road tube station. The church is part of the Diocese of London within the Church of England...

, Middlesex, on 14 December 1626, was the first Duke of Buckingham's

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham KG was the favourite, claimed by some to be the lover, of King James I of England. Despite a very patchy political and military record, he remained at the height of royal favour for the first two years of the reign of Charles I, until he was assassinated...

maternal second cousin once removed, Elizabeth

Elizabeth Richardson, 1st Lady Cramond

Elizabeth Richardson, 1st Lady Cramond was an English writer and peeress.Born Elizabeth Beaumont, she was the eldest child of Sir Thomas Beaumont and his wife, Catherine...

, daughter of Sir Thomas Beaumont of Stoughton, Leicestershire

Stoughton, Leicestershire

Stoughton is a small village and civil parish in the Harborough district of Leicestershire.It is just east of Leicester, and sits in countryside between two protusions of the Leicester urban area . The closest part of the city of Leicester is Evington...

, and widow of Sir John Ashburnham. By his first wife he had twelve children, of whom four daughters and one son, Thomas, survived him. By his second wife he had no issue. She was created on 28 February 1628-9 Lady Cramond

Lord Cramond

The title of Lord Cramond was a title in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created on 23 February 1628 for Dame Elizabeth Richardson. On the death of the fifth lord in 1735, it became extinct.-Lords Cramond :...

in the peerage of Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

, for life, with remainder to her stepson, Sir Thomas Richardson, K.B., who dying in her lifetime on 12 March 1644-5, his son Thomas succeeded to the peerage on her death in April 1651. The title became extinct by the death, without issue, of William, the fifth lord, in 1735.