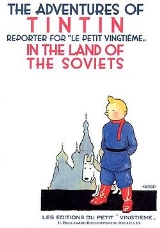

Tintin in the Land of the Soviets

Encyclopedia

Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (in the original French, Les Aventures de Tintin, reporter du "Petit Vingtième", au pays des Soviets) is the first title in the comic book series The Adventures of Tintin

, written and drawn by Belgian cartoonist Hergé

(1907–1983). Originally serialised in the Belgian children's newspaper supplement Le Petit Vingtième

between 10 January 1929 and 8 May 1930, it was subsequently published in book form in 1930. Designed to be a work of anti-Marxist

and anti-socialist

propaganda for children, it was commissioned by Hergé's boss, the Abbé Norbert Wallez

, who ran the right wing Roman Catholic weekly Le XXe Siècle

in which Le Petit Vingtième was published.

The plot revolves around the young Belgian reporter Tintin

and his dog Snowy

, who travel, via Berlin

, to the Soviet Union

, to report back on the policies instituted by the state socialist

government of Joseph Stalin

and the Bolsheviks. However, an agent of the Soviet secret service, the OGPU

, attempts to prevent Tintin from doing so, and sets traps to get rid of him. Despite this, the young reporter is successful in discovering that the Bolsheviks are stealing the food of the Soviet people, rigging elections and murdering opponents.

The success of the work led to Hergé producing further Adventures of Tintin, starting with the controversial Tintin in the Congo

(1930–31), as well as beginning a new comic series, entitled Quick and Flupke. Tintin in the Land of the Soviets was the only one of the 23 completed Tintin adventures that Hergé did not subsequently redraw in a colour edition. He himself thought little of the work, claiming that when he produced it, "I didn't consider it real work... just a game", and later categorising it as simply "a transgression of my youth." Due to this, he prevented its republication, but with the rising production of pirated editions being sold amongst Tintinologists, he finally allowed for an official reprint in 1973, and then an English language

translation in 1989. It is one of only three Adventures of Tintin–the others being Tintin in the Congo and the unfinished Tintin and Alph-Art

—that have not been used as a basis for any theatrical, radio, television or cinematic adaptations.

. Departing from Brussels

, his train is blown up en route to Moscow by an agent of the Soviet secret police, the OGPU

, who believes him to be a "dirty little bourgeois". Tintin is blamed for the bombing by the Berlin

police but escapes to the border of the Soviet Union. Here he is brought before the local Commissar's office, where the same OGPU agent that tried to kill Tintin on the train secretly instructs the Commissar

that they must make the reporter "disappear... accidentally". After escaping again, Tintin finds "how the Soviets fool the poor idiots who still believe in a Red Paradise", by burning bundles of straw and clanging metal in order to trick visiting English Marxists

into believing that Soviet factories are productive, when in fact they are not even operational.

Tintin goes on to witness a local election, where the Bolsheviks aim their guns at the voters to ensure their own electoral success. Several Bolsheviks then come to arrest him during the night, but he manages to scare them off by dressing up as a ghost. Attempting to make his way out of the Soviet Union, he is pursued and arrested, before being threatened with torture. Escaping his captors, he reaches Moscow

, which Tintin remarks has been turned into "a stinking slum" by the Bolsheviks; he then witnesses a government official handing out bread to those homeless children who adhere to the Marxist ideology and denying it to those who do not. Snowy steals a loaf and gives it to a boy who was refused it. Then sneaking into a secret Bolshevik meeting, Tintin learns that all the Soviet grain is being exported abroad for propaganda purposes, leaving the people starving, and that the government plan to "organise an expedition against the kulaks, the rich peasants, and force them at gunpoint to give us their corn."

Tintin infiltrates the Soviet army

and warns some of the kulaks to hide their grain from the army officials, but is caught and sentenced to death by firing squad. By planting blanks

in the soldiers' rifles, Tintin fakes his death and is able to make his way into the snowy wilderness, where he discovers an underground Bolshevik hideaway in a haunted house. Here he is captured by a Bolshevik who informs him that "You're in the hideout where Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin have collected together wealth stolen from the people!" With the help of Snowy, Tintin escapes, commandeers a plane, and flies into the night. The plane crashes, but Tintin fashions himself a new propeller from a tree using a pen knife, and continues to Berlin, where he gets drunk and passes out. Captured by OGPU agents yet again, he is locked in a dungeon, but escapes with the aid of Snowy, who has dressed himself in a tiger costume. Another attempt to kidnap him is foiled when he manages to capture his assailant, an OGPU agent who "intends to blow up all the capitals of Europe

with dynamite". Finally, Tintin arrives back in Brussels to a huge popular reception.

—had been employed to work as an illustrator at Le XXe Siècle

(The 20th Century), a staunchly Roman Catholic and conservative

Belgian newspaper based in Hergé's native Brussels. Run by the Abbé Norbert Wallez

, the paper described itself as a "Catholic Newspaper for Doctrine and Information" and disseminated a far right

and fascist

viewpoint: Wallez himself was a great admirer of Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini

and kept a picture of him on his desktop, while Léon Degrelle

, who would later become the leader of the fascist Rexists

, worked as a foreign correspondent for the paper. As Tintinologist Harry Thompson

would later note, such political ideas were not unusual in Belgium at that time, where "patriotism, Catholicism, strict morality, discipline and naivety were so inextricably bound together in everyone's lives that right-wing politics were an almost inevitable by-product. It was a world view shared by everyone, distinguished principally by its complete ignorance of the world." Anti-socialist sentiment was strong, and a Soviet exhibition held in Brussels in January 1928 was vandalised amidst angry demonstrations by the fascist National Youth Movement, in which Degrelle took part.

Wallez decided to begin production of a children's supplement, Le Petit Vingtième

(The Little Twentieth), which was to be published in Le XXe Siècle every Thursday, and he decided to make Hergé its editor. In addition to his role in editing the supplement, Hergé was initially involved in illustrating a story known as L'extraordinaire aventure de Flup, Nénesse, Puosette et Cochonnet (The Extraordinary Adventures of Flup, Nénesse, Puosette and Cochonnet), which had been written by a member of the newspaper's sport staff and which revolved around the adventures of two boys, one of their little sisters, and her inflatable rubber pig. However Hergé soon became dissatisfied with this simple illustrative task, and wanted to begin both writing and illustrating his own cartoon strip.

He had already had some experience in creating comic strips. From July 1926 he had written a strip entitled Les Aventures de Totor C.P. des Hannetons

(The Adventures of Totor, Scout Leader of the Cockchafers) for the Scouting

newspaper Le Boy Scout Belge (The Belgian Boy Scout), which was based around the life of Totor, a boy scout patrol leader. Tintinologists such as Thompson, Michael Farr

and Pierre Assouline have noted the strong influence that the character of Totor would have on Tintin, with Jean-Marc and Randy Lofficier stating that "Graphically, Totor was virtually identical to Tintin in every respect, except for his scout uniform." Hergé never denied this, and described Tintin as being like Totor's younger brother. The Lofficiers noted many other similarities between Totor and Tintin's respective adventures, particularly in the illustration style, the fast pace of the story, and the use of humour.

.jpg) Hergé wanted to send his newly created character of Tintin on an adventure to the United States

Hergé wanted to send his newly created character of Tintin on an adventure to the United States

, where he could encounter the Native American

s, a people whom Hergé himself had been fascinated with since being a boy scout. Abbé Wallez, however, did not agree with this choice of destination, and Hergé would only be able to achieve it in his third Tintin adventure, Tintin in America

. Instead, Wallez wanted Hergé to send his fictional reporter to the Soviet Union, a country that had been founded in 1922 by the governing Bolshevik Party, a Marxist–Leninist group who had seized power in the Russian Empire

during the October Revolution

of 1917. The Bolsheviks had set about greatly altering the country's society, nationalising industry and replacing a capitalist

economy with a socialist

one, in order to create what they saw as a dictatorship of the proletariat

, or workers' state. By the late 1920s, when Land of the Soviets was written, the Soviet Union's first leader, Vladimir Lenin

, had died and been replaced in this role by the former revolutionary, Joseph Stalin

. Being both Roman Catholic and politically right-wing, Wallez was very much opposed to the atheistic, anti-Christian, and left-wing Soviet government, and wanted Tintin's first adventure to reflect this, thereby indoctrinating its young readers with anti-Marxist and anti-socialist ideas. Later commenting on why he produced a work of propaganda, Hergé said that he had been "inspired by the atmosphere of the paper", which taught him that being a Catholic meant being anti-Marxist.

As Tintinologist Benoît Peeters

noted, Hergé did not have the time either to visit the Soviet Union or to analyse all the published information about it. Instead, he based his information on the country purely upon a single pamphlet, Moscou sans voiles (Moscow Unveiled), which had been written by Joseph Douillet

(1878–1954), a former Belgian consul to Rostov-on-Don

who had spent nine years in Russia following the 1917 revolution

. Published in both Belgium and France in 1928, Moscou sans voiles sold well to a public who were eager to believe Douillet's various anti-Bolshevik claims, many of which were of doubtful accuracy. As Michael Farr noted "Hergé freely, though selectively, lifted whole scenes from Douillet's account", including "the chilling election episode portrated on page 32 of the Tintin book" which was "almost identical" to Douillet's description in Moscou sans voiles.

Hergé's lack of accurate knowledge about the Soviet Union led to many factual mistakes; for instance, the story contains references to bananas, Shell petrol

and Huntley and Palmers biscuits, none of which actually existed in the Soviet Union at the time. Similarly, he made multiple errors in his use of Russian names, typically adding the ending of "-ski" to them, something which is actually the Polish word for "son", rather than Russian, where the equivalent term is "-vitch".

In creating Land of the Soviets, Hergé was also influenced by innovations within the comic strip medium. He noted that he was heavily influenced by the French comics artist Alain Saint-Ogan

, who had recently been producing the Zig et Puce

series. The two would meet the following year, and would become lifelong friends. He was also influenced by the contemporary American comics that the reporter Léon Degrelle had sent back to Belgium from Mexico, where he was stationed to report on the persecution of Catholics. These American comics included George McManus

' Bringing up Father

, George Herriman

's Krazy Kat

and Rudolph Dirks

's Katzenjammer Kids

. Michael Farr also believed that the cinema of the time was an influence upon Tintin in the Land of the Soviets. He highlighted similarities between scenes in the comic with the police chases of the Keystone Cops films, the train chase in Buster Keaton

's The General and with the expressionist

images found in the works of directors like Fritz Lang

. Farr summarised this influence by commenting that "As a pioneer of the strip cartoon, Hergé was not afraid to draw on one modern medium to develop another."

drew a comparison between this and the early European novels of the 18th century, which also often made a pretense of being non-fictional.

The first installment of Tintin in the Land of the Soviets appeared in the 10 January 1929 edition of Le Petit Vingtième, and would subsequently run in the paper in installments every week until 8 May 1930. Hergé had not plotted out the storyline in advance, instead improvising new twists and situations to strand Tintin in on a weekly basis, leading Jean-Marc and Randy Lofficier to remark that "Story-wise and graphically, Hergé was learning his craft before our eyes". Hergé admitted that the work that he produced for the story was rushed, saying that "The Petit Vingtième came out on Wednesday evening, and I often didn't have a clue on Wednesday morning how I was going to get Tintin out of the predicament I had put him in the previous week." Michael Farr believed that this was particularly evident, remarking that the work's composition looked hastily produced, with many drawings being "crude, rudimentary, rushed; there is none of the polish and refinement which subsequent work methods brought." At the same time, however, Farr believed that Land of the Soviets contained "plates of the highest quality where the freedom and confidence of line is proof of Hergé's outstanding ability as a draughtsman."

The story was an immediate success amongst its young readers. As Harry Thompson noted, the plotline would have been popular with the average Belgian parent, exploiting their anti-socialist sentiment and feeding their fears that the Russians were a malevolent people. Indeed, the popularity of the series led Wallez to decide on performing publicity stunts to increase interest in it: the first of these was the publication of a faked letter on April Fool's Day claiming to be from the Soviet secret police and confirming the existence of Tintin the reporter. The second was a staged publicity event, suggested by the reporter Charles Lesne, that took place on Thursday 8 May 1930. During the stunt, an actor named Henri de Donckers was employed to portray Tintin, dressed in stereotypical Russian clothing and bringing along a white dog on a lead, representing Snowy. De Donckers was then accompanied by Hergé and ordered to get off of the train from Moscow that was pulling in to Brussels' Gare du Nord

. Both the actor and Hergé were greeted by an adoring crowd of avid fans, who mobbed De Donckers and pulled him into their midst. The duo then took a Buick limousine to the offices of Le Vingtième Siècle, where they were greeted by further crowds, and so standing upon the building's balcony, Hergé gave a speech before presents were distributed amongst the assembled fans.

Tintin in the Land of the Soviets also began serialisation in a French Catholic magazine, Coeurs Vaillants (Valiant Hearts), from 26 October 1930 onward. The success of the strip meant that the story was then assembled and published in book form by the Brussels-based Editions du Petit Vingtième, with a print run of 10,000, in French

only, the first five hundred of which were numbered.

, he chose not to redraw Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, believing that the story was too crude. He was embarrassed by it, labelling it a "transgression of my youth". Jean-Marc and Randy Lofficier believed that another factor in his decision not to redraw it might have been that the story was too virulently anti-Marxist in a period when many across Western Europe were sympathetic to Marxism following the Second World War.

As The Adventures of Tintin became more popular in Western Europe, and some of the rarer books became collectors items, the original printed edition of Tintin in the Land of the Soviets became highly valued. Because of this, Studio Hergé brought out 500 numbered copies to mark the series' 40th birthday in 1969. Nonetheless, this only encouraged a larger demand for the book, and soon a "number of mediocre-quality pirated editions" were produced and sold at "very high prices." To stem this illegal trade, Hergé agreed that it could be published in 1973 as a part of the Archives Hergé collection, where it was released in a collected volume along with Tintin in the Congo and Tintin in America. The release of pirated editions however continued, and so it was decided that a facsimile edition of the original would be published through Casterman in 1981. Over the next decade it would be translated into nine different languages, with an English language edition being published by Sundancer in 1989, translated by Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper and Michael Turner.

Sociologist John Theobald noted that by the 1980s, when the book had begun to see widespread publication in the western world, the plot was being "rendered socially and politically acceptable in the climate of the Reaganite

repolarisation of the 'Cold War

' and the final push towards the demise of the Soviet Union". It was because of the new political acceptability of the comic's anti-Soviet themes that it was "to be found on hypermarket shelves as suitable children's literature for the new millennium."

The Adventures of Tintin

The Adventures of Tintin is a series of classic comic books created by Belgian artist , who wrote under the pen name of Hergé...

, written and drawn by Belgian cartoonist Hergé

Hergé

Georges Prosper Remi , better known by the pen name Hergé, was a Belgian comics writer and artist. His best known and most substantial work is the 23 completed comic books in The Adventures of Tintin series, which he wrote and illustrated from 1929 until his death in 1983, although he was also...

(1907–1983). Originally serialised in the Belgian children's newspaper supplement Le Petit Vingtième

Le Petit Vingtième

Le Petit Vingtième was the weekly youth supplement to the Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle from 1928 to 1940. The comics series The Adventures of Tintin first appeared in its pages.-History:...

between 10 January 1929 and 8 May 1930, it was subsequently published in book form in 1930. Designed to be a work of anti-Marxist

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

and anti-socialist

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

propaganda for children, it was commissioned by Hergé's boss, the Abbé Norbert Wallez

Norbert Wallez

Abbé Norbert Wallez was a Belgian priest and journalist. He was the editor of the newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle , whose youth supplement, Le Petit Vingtième, first published The Adventures of Tintin.Wallez studied at the University of Leuven...

, who ran the right wing Roman Catholic weekly Le XXe Siècle

Le XXe Siècle

Le XXe Siècle was a Belgian newspaper that was published from 1895 and 1940. Its supplement Le Petit Vingtième is known as the first publication to feature The Adventures of Tintin....

in which Le Petit Vingtième was published.

The plot revolves around the young Belgian reporter Tintin

Tintin (character)

Tintin is a fictional character in The Adventures of Tintin, the series of classic Belgian comic books written and illustrated by Hergé. Tintin is the protagonist of the series, a reporter and adventurer who travels around the world with his dog Snowy....

and his dog Snowy

Snowy (character)

Snowy is a fictional character in The Adventures of Tintin, the series of classic Belgian comic books written and illustrated by Hergé. He is a white Wire Fox Terrier and Tintin's four-legged companion who travels everywhere with him...

, who travel, via Berlin

Berlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

, to the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, to report back on the policies instituted by the state socialist

State socialism

State socialism is an economic system with limited socialist characteristics, such as public ownership of major industries, remedial measures to benefit the working class, and a gradual process of developing socialism through government policy...

government of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

and the Bolsheviks. However, an agent of the Soviet secret service, the OGPU

State Political Directorate

The State Political Directorate was the secret police of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1934...

, attempts to prevent Tintin from doing so, and sets traps to get rid of him. Despite this, the young reporter is successful in discovering that the Bolsheviks are stealing the food of the Soviet people, rigging elections and murdering opponents.

The success of the work led to Hergé producing further Adventures of Tintin, starting with the controversial Tintin in the Congo

Tintin in the Congo

Tintin in the Congo is the second title in the comicbook series The Adventures of Tintin, written and drawn by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. Originally serialised in the Belgian children's newspaper supplement, Le Petit Vingtième between June 1930 and July 1931, it was first published in book form...

(1930–31), as well as beginning a new comic series, entitled Quick and Flupke. Tintin in the Land of the Soviets was the only one of the 23 completed Tintin adventures that Hergé did not subsequently redraw in a colour edition. He himself thought little of the work, claiming that when he produced it, "I didn't consider it real work... just a game", and later categorising it as simply "a transgression of my youth." Due to this, he prevented its republication, but with the rising production of pirated editions being sold amongst Tintinologists, he finally allowed for an official reprint in 1973, and then an English language

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

translation in 1989. It is one of only three Adventures of Tintin–the others being Tintin in the Congo and the unfinished Tintin and Alph-Art

Tintin and Alph-Art

Tintin and Alph-Art was the intended twenty-fourth and final book in the Tintin series, created by Belgian comics artist Hergé. It is a striking departure from the earlier books in tone and subject, as well as in some parts of the style; rather than being set in a usual exotic and action-packed...

—that have not been used as a basis for any theatrical, radio, television or cinematic adaptations.

Plot

Tintin, a reporter for Le Petit Vingtième, and his dog Snowy are sent on an assignment to the Soviet UnionSoviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

. Departing from Brussels

Brussels

Brussels , officially the Brussels Region or Brussels-Capital Region , is the capital of Belgium and the de facto capital of the European Union...

, his train is blown up en route to Moscow by an agent of the Soviet secret police, the OGPU

State Political Directorate

The State Political Directorate was the secret police of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1934...

, who believes him to be a "dirty little bourgeois". Tintin is blamed for the bombing by the Berlin

Berlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

police but escapes to the border of the Soviet Union. Here he is brought before the local Commissar's office, where the same OGPU agent that tried to kill Tintin on the train secretly instructs the Commissar

Commissar

Commissar is the English transliteration of an official title used in Russia from the time of Peter the Great.The title was used during the Provisional Government for regional heads of administration, but it is mostly associated with a number of Cheka and military functions in Bolshevik and Soviet...

that they must make the reporter "disappear... accidentally". After escaping again, Tintin finds "how the Soviets fool the poor idiots who still believe in a Red Paradise", by burning bundles of straw and clanging metal in order to trick visiting English Marxists

Communist Party of Great Britain

The Communist Party of Great Britain was the largest communist party in Great Britain, although it never became a mass party like those in France and Italy. It existed from 1920 to 1991.-Formation:...

into believing that Soviet factories are productive, when in fact they are not even operational.

Tintin goes on to witness a local election, where the Bolsheviks aim their guns at the voters to ensure their own electoral success. Several Bolsheviks then come to arrest him during the night, but he manages to scare them off by dressing up as a ghost. Attempting to make his way out of the Soviet Union, he is pursued and arrested, before being threatened with torture. Escaping his captors, he reaches Moscow

Moscow

Moscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

, which Tintin remarks has been turned into "a stinking slum" by the Bolsheviks; he then witnesses a government official handing out bread to those homeless children who adhere to the Marxist ideology and denying it to those who do not. Snowy steals a loaf and gives it to a boy who was refused it. Then sneaking into a secret Bolshevik meeting, Tintin learns that all the Soviet grain is being exported abroad for propaganda purposes, leaving the people starving, and that the government plan to "organise an expedition against the kulaks, the rich peasants, and force them at gunpoint to give us their corn."

Tintin infiltrates the Soviet army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

and warns some of the kulaks to hide their grain from the army officials, but is caught and sentenced to death by firing squad. By planting blanks

Blank (cartridge)

A blank is a type of cartridge for a firearm that contains gunpowder but no bullet or shot. When fired, the blank makes a flash and an explosive sound . Blanks are often used for simulation , training, and for signaling...

in the soldiers' rifles, Tintin fakes his death and is able to make his way into the snowy wilderness, where he discovers an underground Bolshevik hideaway in a haunted house. Here he is captured by a Bolshevik who informs him that "You're in the hideout where Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin have collected together wealth stolen from the people!" With the help of Snowy, Tintin escapes, commandeers a plane, and flies into the night. The plane crashes, but Tintin fashions himself a new propeller from a tree using a pen knife, and continues to Berlin, where he gets drunk and passes out. Captured by OGPU agents yet again, he is locked in a dungeon, but escapes with the aid of Snowy, who has dressed himself in a tiger costume. Another attempt to kidnap him is foiled when he manages to capture his assailant, an OGPU agent who "intends to blow up all the capitals of Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

with dynamite". Finally, Tintin arrives back in Brussels to a huge popular reception.

Background

Georges Remi—who would become better known under his pen name of HergéHergé

Georges Prosper Remi , better known by the pen name Hergé, was a Belgian comics writer and artist. His best known and most substantial work is the 23 completed comic books in The Adventures of Tintin series, which he wrote and illustrated from 1929 until his death in 1983, although he was also...

—had been employed to work as an illustrator at Le XXe Siècle

Le XXe Siècle

Le XXe Siècle was a Belgian newspaper that was published from 1895 and 1940. Its supplement Le Petit Vingtième is known as the first publication to feature The Adventures of Tintin....

(The 20th Century), a staunchly Roman Catholic and conservative

Social conservatism

Social Conservatism is primarily a political, and usually morally influenced, ideology that focuses on the preservation of what are seen as traditional values. Social conservatism is a form of authoritarianism often associated with the position that the federal government should have a greater role...

Belgian newspaper based in Hergé's native Brussels. Run by the Abbé Norbert Wallez

Norbert Wallez

Abbé Norbert Wallez was a Belgian priest and journalist. He was the editor of the newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle , whose youth supplement, Le Petit Vingtième, first published The Adventures of Tintin.Wallez studied at the University of Leuven...

, the paper described itself as a "Catholic Newspaper for Doctrine and Information" and disseminated a far right

Far right

Far-right, extreme right, hard right, radical right, and ultra-right are terms used to discuss the qualitative or quantitative position a group or person occupies within right-wing politics. Far-right politics may involve anti-immigration and anti-integration stances towards groups that are...

and fascist

Fascism

Fascism is a radical authoritarian nationalist political ideology. Fascists seek to rejuvenate their nation based on commitment to the national community as an organic entity, in which individuals are bound together in national identity by suprapersonal connections of ancestry, culture, and blood...

viewpoint: Wallez himself was a great admirer of Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was an Italian politician who led the National Fascist Party and is credited with being one of the key figures in the creation of Fascism....

and kept a picture of him on his desktop, while Léon Degrelle

Léon Degrelle

Léon Joseph Marie Ignace Degrelle was a Walloon Belgian politician, who founded Rexism and later joined the Waffen SS which were front-line troops in the fight against the Soviet Union...

, who would later become the leader of the fascist Rexists

Rexism

Rexism was a fascist political movement in the first half of the 20th century in Belgium.It was the ideology of the Rexist Party , officially called Rex, founded in 1930 by Léon Degrelle, a Walloon...

, worked as a foreign correspondent for the paper. As Tintinologist Harry Thompson

Harry Thompson

Harry William Thompson was an English radio and television producer, comedy writer, novelist and biographer....

would later note, such political ideas were not unusual in Belgium at that time, where "patriotism, Catholicism, strict morality, discipline and naivety were so inextricably bound together in everyone's lives that right-wing politics were an almost inevitable by-product. It was a world view shared by everyone, distinguished principally by its complete ignorance of the world." Anti-socialist sentiment was strong, and a Soviet exhibition held in Brussels in January 1928 was vandalised amidst angry demonstrations by the fascist National Youth Movement, in which Degrelle took part.

Wallez decided to begin production of a children's supplement, Le Petit Vingtième

Le Petit Vingtième

Le Petit Vingtième was the weekly youth supplement to the Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle from 1928 to 1940. The comics series The Adventures of Tintin first appeared in its pages.-History:...

(The Little Twentieth), which was to be published in Le XXe Siècle every Thursday, and he decided to make Hergé its editor. In addition to his role in editing the supplement, Hergé was initially involved in illustrating a story known as L'extraordinaire aventure de Flup, Nénesse, Puosette et Cochonnet (The Extraordinary Adventures of Flup, Nénesse, Puosette and Cochonnet), which had been written by a member of the newspaper's sport staff and which revolved around the adventures of two boys, one of their little sisters, and her inflatable rubber pig. However Hergé soon became dissatisfied with this simple illustrative task, and wanted to begin both writing and illustrating his own cartoon strip.

He had already had some experience in creating comic strips. From July 1926 he had written a strip entitled Les Aventures de Totor C.P. des Hannetons

Totor

Totor, Chief Scout of the Cockchafers is the first comic strip series written by Hergé who later wrote The Adventures of Tintin. Le Boy Scout Belge published it monthly from July 1926 to summer 1929 and tells of a Boy Scout called Totor on his adventures...

(The Adventures of Totor, Scout Leader of the Cockchafers) for the Scouting

Scouting

Scouting, also known as the Scout Movement, is a worldwide youth movement with the stated aim of supporting young people in their physical, mental and spiritual development, that they may play constructive roles in society....

newspaper Le Boy Scout Belge (The Belgian Boy Scout), which was based around the life of Totor, a boy scout patrol leader. Tintinologists such as Thompson, Michael Farr

Michael Farr

Michael Farr is a British expert on the comic series Tintin and its creator, Hergé. He has written several books on the subject as well as translating several others into English...

and Pierre Assouline have noted the strong influence that the character of Totor would have on Tintin, with Jean-Marc and Randy Lofficier stating that "Graphically, Totor was virtually identical to Tintin in every respect, except for his scout uniform." Hergé never denied this, and described Tintin as being like Totor's younger brother. The Lofficiers noted many other similarities between Totor and Tintin's respective adventures, particularly in the illustration style, the fast pace of the story, and the use of humour.

Influences

.jpg)

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, where he could encounter the Native American

Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The indigenous peoples of the Americas are the pre-Columbian inhabitants of North and South America, their descendants and other ethnic groups who are identified with those peoples. Indigenous peoples are known in Canada as Aboriginal peoples, and in the United States as Native Americans...

s, a people whom Hergé himself had been fascinated with since being a boy scout. Abbé Wallez, however, did not agree with this choice of destination, and Hergé would only be able to achieve it in his third Tintin adventure, Tintin in America

Tintin in America

Tintin in America is the third title in the comic book series The Adventures of Tintin, written and drawn by Belgian cartoonist Hergé...

. Instead, Wallez wanted Hergé to send his fictional reporter to the Soviet Union, a country that had been founded in 1922 by the governing Bolshevik Party, a Marxist–Leninist group who had seized power in the Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

during the October Revolution

October Revolution

The October Revolution , also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution , Red October, the October Uprising or the Bolshevik Revolution, was a political revolution and a part of the Russian Revolution of 1917...

of 1917. The Bolsheviks had set about greatly altering the country's society, nationalising industry and replacing a capitalist

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

economy with a socialist

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

one, in order to create what they saw as a dictatorship of the proletariat

Dictatorship of the proletariat

In Marxist socio-political thought, the dictatorship of the proletariat refers to a socialist state in which the proletariat, or the working class, have control of political power. The term, coined by Joseph Weydemeyer, was adopted by the founders of Marxism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, in the...

, or workers' state. By the late 1920s, when Land of the Soviets was written, the Soviet Union's first leader, Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and communist politician who led the October Revolution of 1917. As leader of the Bolsheviks, he headed the Soviet state during its initial years , as it fought to establish control of Russia in the Russian Civil War and worked to create a...

, had died and been replaced in this role by the former revolutionary, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

. Being both Roman Catholic and politically right-wing, Wallez was very much opposed to the atheistic, anti-Christian, and left-wing Soviet government, and wanted Tintin's first adventure to reflect this, thereby indoctrinating its young readers with anti-Marxist and anti-socialist ideas. Later commenting on why he produced a work of propaganda, Hergé said that he had been "inspired by the atmosphere of the paper", which taught him that being a Catholic meant being anti-Marxist.

As Tintinologist Benoît Peeters

Benoît Peeters

Benoît Peeters is a comics writer, novelist, and critic. He has lived in Belgium since 1978.His best-known work is Les Cités Obscures, an imaginary world which mingles a Borgesian metaphysical surrealism with the detailed architectural vistas of the series' artist, François Schuiten...

noted, Hergé did not have the time either to visit the Soviet Union or to analyse all the published information about it. Instead, he based his information on the country purely upon a single pamphlet, Moscou sans voiles (Moscow Unveiled), which had been written by Joseph Douillet

Joseph Douillet

Joseph Douillet was a Belgian diplomat to the USSR known as the author of Moscou sans Voiles: Neuf ans de travail au pays des Soviets published in 1928....

(1878–1954), a former Belgian consul to Rostov-on-Don

Rostov-on-Don

-History:The mouth of the Don River has been of great commercial and cultural importance since the ancient times. It was the site of the Greek colony Tanais, of the Genoese fort Tana, and of the Turkish fortress Azak...

who had spent nine years in Russia following the 1917 revolution

Russian Revolution

Russian Revolution can refer to:* Russian Revolution , a series of strikes and uprisings against Nicholas II, resulting in the creation of State Duma.* Russian Revolution...

. Published in both Belgium and France in 1928, Moscou sans voiles sold well to a public who were eager to believe Douillet's various anti-Bolshevik claims, many of which were of doubtful accuracy. As Michael Farr noted "Hergé freely, though selectively, lifted whole scenes from Douillet's account", including "the chilling election episode portrated on page 32 of the Tintin book" which was "almost identical" to Douillet's description in Moscou sans voiles.

Hergé's lack of accurate knowledge about the Soviet Union led to many factual mistakes; for instance, the story contains references to bananas, Shell petrol

Royal Dutch Shell

Royal Dutch Shell plc , commonly known as Shell, is a global oil and gas company headquartered in The Hague, Netherlands and with its registered office in London, United Kingdom. It is the fifth-largest company in the world according to a composite measure by Forbes magazine and one of the six...

and Huntley and Palmers biscuits, none of which actually existed in the Soviet Union at the time. Similarly, he made multiple errors in his use of Russian names, typically adding the ending of "-ski" to them, something which is actually the Polish word for "son", rather than Russian, where the equivalent term is "-vitch".

In creating Land of the Soviets, Hergé was also influenced by innovations within the comic strip medium. He noted that he was heavily influenced by the French comics artist Alain Saint-Ogan

Alain Saint-Ogan

Alain Saint-Ogan was a French comics author and artist.-Biography:In 1925, he created the well-known comic strip Zig et Puce , which initially appeared in the Dimanche Illustré , the weekly youth supplement of the French daily newspaper, l'Excelsior.His other comic...

, who had recently been producing the Zig et Puce

Zig et Puce

Zig et Puce is a Franco-Belgian comics series created by Alain Saint-Ogan in 1925 that became popular and influential over a long period. After ending production, it was revived by Greg for a second successful publication run.-Synopsis :...

series. The two would meet the following year, and would become lifelong friends. He was also influenced by the contemporary American comics that the reporter Léon Degrelle had sent back to Belgium from Mexico, where he was stationed to report on the persecution of Catholics. These American comics included George McManus

George McManus

George McManus was an American cartoonist best known as the creator of Irish immigrant Jiggs and his wife Maggie, the central characters in his syndicated comic strip, Bringing Up Father....

' Bringing up Father

Bringing up Father

Bringing Up Father was an influential American comic strip created by cartoonist George McManus . Distributed by King Features Syndicate, it ran for 87 years, from January 12, 1913 to May 28, 2000....

, George Herriman

George Herriman

George Joseph Herriman was an American cartoonist, best known for his classic comic strip Krazy Kat.-Early life:...

's Krazy Kat

Krazy Kat

Krazy Kat is an American comic strip created by cartoonist George Herriman, published daily in newspapers between 1913 and 1944. It first appeared in the New York Evening Journal, whose owner, William Randolph Hearst, was a major booster for the strip throughout its run...

and Rudolph Dirks

Rudolph Dirks

Rudolph Dirks was one of the earliest and most noted comic strip artists....

's Katzenjammer Kids

Katzenjammer Kids

The Katzenjammer Kids is an American comic strip created by the German immigrant Rudolph Dirks and drawn by Harold H. Knerr for 37 years...

. Michael Farr also believed that the cinema of the time was an influence upon Tintin in the Land of the Soviets. He highlighted similarities between scenes in the comic with the police chases of the Keystone Cops films, the train chase in Buster Keaton

Buster Keaton

Joseph Frank "Buster" Keaton was an American comic actor, filmmaker, producer and writer. He was best known for his silent films, in which his trademark was physical comedy with a consistently stoic, deadpan expression, earning him the nickname "The Great Stone Face".Keaton was recognized as the...

's The General and with the expressionist

Expressionism

Expressionism was a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it radically for emotional effect in order to evoke moods or ideas...

images found in the works of directors like Fritz Lang

Fritz Lang

Friedrich Christian Anton "Fritz" Lang was an Austrian-American filmmaker, screenwriter, and occasional film producer and actor. One of the best known émigrés from Germany's school of Expressionism, he was dubbed the "Master of Darkness" by the British Film Institute...

. Farr summarised this influence by commenting that "As a pioneer of the strip cartoon, Hergé was not afraid to draw on one modern medium to develop another."

Publication

In advertising the upcoming story prior to serialisation, an announcement was featured in the 4 January 1929 edition of Le Petit Vingtième, proclaiming that "we are always eager to satisfy our readers and keep them up to date on foreign affairs. We have therefore sent TINTIN, one of our top reporters, to Soviet Russia." The illusion that Tintin was actually a real reporter for the paper, and not a fictional character, was supported by the claim that the ensuing comic strip was not a series of drawings, but was actually composed of photographs taken of Tintin's adventure. Literary critic Tom McCarthyTom McCarthy (writer)

-Life and work:Tom McCarthy is a writer and conceptual artist. He was born in 1969 and lives in central London. McCarthy grew up in Greenwich, south London and was educated at Dulwich College and later New College, Oxford, where he studied English literature. He lived in Prague, Berlin and...

drew a comparison between this and the early European novels of the 18th century, which also often made a pretense of being non-fictional.

The first installment of Tintin in the Land of the Soviets appeared in the 10 January 1929 edition of Le Petit Vingtième, and would subsequently run in the paper in installments every week until 8 May 1930. Hergé had not plotted out the storyline in advance, instead improvising new twists and situations to strand Tintin in on a weekly basis, leading Jean-Marc and Randy Lofficier to remark that "Story-wise and graphically, Hergé was learning his craft before our eyes". Hergé admitted that the work that he produced for the story was rushed, saying that "The Petit Vingtième came out on Wednesday evening, and I often didn't have a clue on Wednesday morning how I was going to get Tintin out of the predicament I had put him in the previous week." Michael Farr believed that this was particularly evident, remarking that the work's composition looked hastily produced, with many drawings being "crude, rudimentary, rushed; there is none of the polish and refinement which subsequent work methods brought." At the same time, however, Farr believed that Land of the Soviets contained "plates of the highest quality where the freedom and confidence of line is proof of Hergé's outstanding ability as a draughtsman."

The story was an immediate success amongst its young readers. As Harry Thompson noted, the plotline would have been popular with the average Belgian parent, exploiting their anti-socialist sentiment and feeding their fears that the Russians were a malevolent people. Indeed, the popularity of the series led Wallez to decide on performing publicity stunts to increase interest in it: the first of these was the publication of a faked letter on April Fool's Day claiming to be from the Soviet secret police and confirming the existence of Tintin the reporter. The second was a staged publicity event, suggested by the reporter Charles Lesne, that took place on Thursday 8 May 1930. During the stunt, an actor named Henri de Donckers was employed to portray Tintin, dressed in stereotypical Russian clothing and bringing along a white dog on a lead, representing Snowy. De Donckers was then accompanied by Hergé and ordered to get off of the train from Moscow that was pulling in to Brussels' Gare du Nord

Brussels-North railway station

Bruxelles-Nord / Brussel-Noord is one of the three major railway stations in Brussels; the other two are Brussels Central and Brussels South...

. Both the actor and Hergé were greeted by an adoring crowd of avid fans, who mobbed De Donckers and pulled him into their midst. The duo then took a Buick limousine to the offices of Le Vingtième Siècle, where they were greeted by further crowds, and so standing upon the building's balcony, Hergé gave a speech before presents were distributed amongst the assembled fans.

Tintin in the Land of the Soviets also began serialisation in a French Catholic magazine, Coeurs Vaillants (Valiant Hearts), from 26 October 1930 onward. The success of the strip meant that the story was then assembled and published in book form by the Brussels-based Editions du Petit Vingtième, with a print run of 10,000, in French

French language

French is a Romance language spoken as a first language in France, the Romandy region in Switzerland, Wallonia and Brussels in Belgium, Monaco, the regions of Quebec and Acadia in Canada, and by various communities elsewhere. Second-language speakers of French are distributed throughout many parts...

only, the first five hundred of which were numbered.

Later publications

When, from 1942 onwards, Hergé began redrawing his earlier Tintin stories for the modernised colour versions at CastermanCasterman

Casterman is a publisher of Franco-Belgian comics, specializing in comic books and children's literature. The company is based in Tournai, Belgium.Founded in 1780, Casterman was originally a printing company and publishing house...

, he chose not to redraw Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, believing that the story was too crude. He was embarrassed by it, labelling it a "transgression of my youth". Jean-Marc and Randy Lofficier believed that another factor in his decision not to redraw it might have been that the story was too virulently anti-Marxist in a period when many across Western Europe were sympathetic to Marxism following the Second World War.

As The Adventures of Tintin became more popular in Western Europe, and some of the rarer books became collectors items, the original printed edition of Tintin in the Land of the Soviets became highly valued. Because of this, Studio Hergé brought out 500 numbered copies to mark the series' 40th birthday in 1969. Nonetheless, this only encouraged a larger demand for the book, and soon a "number of mediocre-quality pirated editions" were produced and sold at "very high prices." To stem this illegal trade, Hergé agreed that it could be published in 1973 as a part of the Archives Hergé collection, where it was released in a collected volume along with Tintin in the Congo and Tintin in America. The release of pirated editions however continued, and so it was decided that a facsimile edition of the original would be published through Casterman in 1981. Over the next decade it would be translated into nine different languages, with an English language edition being published by Sundancer in 1989, translated by Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper and Michael Turner.

Sociologist John Theobald noted that by the 1980s, when the book had begun to see widespread publication in the western world, the plot was being "rendered socially and politically acceptable in the climate of the Reaganite

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan was the 40th President of the United States , the 33rd Governor of California and, prior to that, a radio, film and television actor....

repolarisation of the 'Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

' and the final push towards the demise of the Soviet Union". It was because of the new political acceptability of the comic's anti-Soviet themes that it was "to be found on hypermarket shelves as suitable children's literature for the new millennium."

Critical reception

In his study of the cultural and literary legacy of Brussels, André De Vries remarked that Tintin in the Land of the Soviets was "crude by Hergé's later standards, in every sense of the word."Sociologist John Theobald claimed that Hergé's depiction of the Bolsheviks rigging elections, killing opponents and stealing the grain from the people were non-factual, and were done in order to portray them in a negative light in the minds of his young readers. Hergé displayed the Bolsheviks and their Marxist-Leninist ideology as being "absolute Evil", and set Tintin to fight against them, but as Jean-Marie Apostolidès noted, "because [Tintin] does not understand [the Soviet government's] origin, he does not directly engage with but merely observes this world of misery", simply fighting Bolsheviks rather than fomenting counter-revolution to actively overthrow them.External links

- Tintin in the Land of the Soviets at Tintinologist.org