Titus Oates

Encyclopedia

Perjury

Perjury, also known as forswearing, is the willful act of swearing a false oath or affirmation to tell the truth, whether spoken or in writing, concerning matters material to a judicial proceeding. That is, the witness falsely promises to tell the truth about matters which affect the outcome of the...

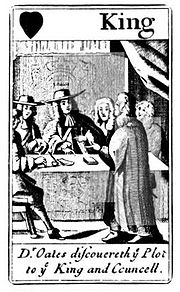

who fabricated the "Popish Plot

Popish Plot

The Popish Plot was a fictitious conspiracy concocted by Titus Oates that gripped England, Wales and Scotland in Anti-Catholic hysteria between 1678 and 1681. Oates alleged that there existed an extensive Catholic conspiracy to assassinate Charles II, accusations that led to the execution of at...

", a supposed Catholic

Catholicism

Catholicism is a broad term for the body of the Catholic faith, its theologies and doctrines, its liturgical, ethical, spiritual, and behavioral characteristics, as well as a religious people as a whole....

conspiracy to kill King Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

.

Early life

Titus Oates was born in OakhamOakham

-Oakham's horseshoes:Traditionally, members of royalty and peers of the realm who visited or passed through the town had to pay a forfeit in the form of a horseshoe...

. His father, Samuel, was the director of Marsham

Marsham, Norfolk

Marsham is a civil parish in the English county of Norfolk, about north of Norwich.It covers an area of and had a population of 674 in 282 households as of the 2001 census.For the purposes of local government, it falls within the district of Broadland....

in Norfolk

Norfolk

Norfolk is a low-lying county in the East of England. It has borders with Lincolnshire to the west, Cambridgeshire to the west and southwest and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the North Sea coast and to the north-west the county is bordered by The Wash. The county...

before becoming an Anabaptist

Anabaptist

Anabaptists are Protestant Christians of the Radical Reformation of 16th-century Europe, and their direct descendants, particularly the Amish, Brethren, Hutterites, and Mennonites....

during the Puritan Revolution and rejoining the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

at the Restoration

English Restoration

The Restoration of the English monarchy began in 1660 when the English, Scottish and Irish monarchies were all restored under Charles II after the Interregnum that followed the Wars of the Three Kingdoms...

. Oates was educated at Merchant Taylors' School

Merchant Taylors' School, Northwood

Merchant Taylors' School is a British independent day school for boys, originally located in the City of London. Since 1933 it has been located at Sandy Lodge in the Three Rivers district of Hertfordshire ....

, Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

Gonville and Caius College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England. The college is often referred to simply as "Caius" , after its second founder, John Keys, who fashionably latinised the spelling of his name after studying in Italy.- Outline :Gonville and...

, and St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college's alumni include nine Nobel Prize winners, six Prime Ministers, three archbishops, at least two princes, and three Saints....

. Known as a less than astute student, he was ejected from both colleges. A few months later, he became an Anglican priest and Vicar

Vicar

In the broadest sense, a vicar is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior . In this sense, the title is comparable to lieutenant...

of the parish of Bobbing

Bobbing, Kent

Bobbing is a village and civil parish in the Swale district of Kent, England, about a mile north-west of Sittingbourne, and forming part of its urban area. According to the 2001 census the parish had a population of 1,694....

in Kent

Kent

Kent is a county in southeast England, and is one of the home counties. It borders East Sussex, Surrey and Greater London and has a defined boundary with Essex in the middle of the Thames Estuary. The ceremonial county boundaries of Kent include the shire county of Kent and the unitary borough of...

. During this time Oates was charged with perjury having accused a schoolmaster

Schoolmaster

A schoolmaster, or simply master, once referred to a male school teacher. This usage survives in British public schools, but is generally obsolete elsewhere.The teacher in charge of a school is the headmaster...

in Hastings

Hastings

Hastings is a town and borough in the county of East Sussex on the south coast of England. The town is located east of the county town of Lewes and south east of London, and has an estimated population of 86,900....

of sodomy

Sodomy

Sodomy is an anal or other copulation-like act, especially between male persons or between a man and animal, and one who practices sodomy is a "sodomite"...

. Oates was put in jail, but escaped and fled to London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

.

In 1677 he got himself appointed as a chaplain

Chaplain

Traditionally, a chaplain is a minister in a specialized setting such as a priest, pastor, rabbi, or imam or lay representative of a religion attached to a secular institution such as a hospital, prison, military unit, police department, university, or private chapel...

of the ship Adventurer in the English navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

. He was soon accused of buggery

Buggery Act 1533

The Buggery Act 1533, formally An Acte for the punysshement of the vice of Buggerie , was an Act of the Parliament of England that was passed during the reign of Henry VIII...

(i.e., sodomy, which was a capital offence in England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

at the time) and spared only because of his clergyman's status.

After the navy he joined the household of the Catholic Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk

The Duke of Norfolk is the premier duke in the peerage of England, and also, as Earl of Arundel, the premier earl. The Duke of Norfolk is, moreover, the Earl Marshal and hereditary Marshal of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the...

as an Anglican chaplain. On Ash Wednesday

Ash Wednesday

Ash Wednesday, in the calendar of Western Christianity, is the first day of Lent and occurs 46 days before Easter. It is a moveable fast, falling on a different date each year because it is dependent on the date of Easter...

in 1677 he was received into the Catholic Church. Oddly, at the same time Oates agreed to co-author a series of anti-Catholic pamphlets with Israel Tonge

Israel Tonge

Israel Tonge , aka Ezerel or Ezreel Tongue, was an English divine and an informer in the "Popish" plot. He was born at Tickhill, near Doncaster, the son of Henry Tongue, minister of Holtby, Yorkshire...

, whom he had met through his father Samuel, who had once more reverted to the Baptist doctrine.

He is described by Dryden

John Dryden

John Dryden was an influential English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who dominated the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the period came to be known in literary circles as the Age of Dryden.Walter Scott called him "Glorious John." He was made Poet...

in Absalom and Achitophel

Absalom and Achitophel

Absalom and Achitophel is a landmark poetic political satire by John Dryden. The poem exists in two parts. The first part, of 1681, is undoubtedly by Dryden...

thus—

Contact with the Jesuits

Oates was involved with the Jesuit houses of St. Omer (in FranceFrance

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

) and the Royal English College

English College, Valladolid

The Royal English and Welsh College, Valladolid, under the patronage of St Alban, was founded in 1589 during the protestant reformation for the training of Catholic priests for the English and Welsh Mission....

at Valladolid

Valladolid

Valladolid is a historic city and municipality in north-central Spain, situated at the confluence of the Pisuerga and Esgueva rivers, and located within three wine-making regions: Ribera del Duero, Rueda and Cigales...

, Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

(like many diocesan

Diocese

A diocese is the district or see under the supervision of a bishop. It is divided into parishes.An archdiocese is more significant than a diocese. An archdiocese is presided over by an archbishop whose see may have or had importance due to size or historical significance...

seminaries

Seminary

A seminary, theological college, or divinity school is an institution of secondary or post-secondary education for educating students in theology, generally to prepare them for ordination as clergy or for other ministry...

of the day, this was a Jesuit-run institution). Oates was admitted to the course in Valladolid by the support of Richard Strange

Richard Strange (Jesuit)

Richard Strange was an English Jesuit, now remembered as the sponsor for Titus Oates's short period of studies under the Society of Jesus, despite Oates's lack of Latin and poor reputation.-Life:...

, despite a lack of basic competence in Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

. He later claimed, falsely, that he had become a Catholic Doctor of Divinity

Doctor of Divinity

Doctor of Divinity is an advanced academic degree in divinity. Historically, it identified one who had been licensed by a university to teach Christian theology or related religious subjects....

. Thomas Whitbread

Thomas Whitbread

Blessed Thomas Whitbread was an English Jesuit missionary, wrongly convicted of conspiracy to murder Charles II of England. He was beatified in 1929.-Life:...

took a much firmer line with Oates than had Strange and, in June 1678, expelled him from St. Omer.

When he returned to London, he rekindled his friendship with Israel Tonge. Oates explained that he had pretended to become a Catholic to learn about the secrets of the Jesuits and that, before leaving, he had heard about a planned Jesuit meeting in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

.

The Fabricated Popish Plot

Oates and Tonge wrote a lengthy manuscript that accused the Catholic Church authorities in Britain of approving an assassination of Charles II. The Jesuits were supposedly to carry out the task. In August 1678, King Charles was warned of this alleged plot against his life by the chemist Christopher Kirkby, and later by Tonge. Charles was unimpressed, but handed the matter over to one of his ministers, Thomas Osborne, the Earl of DanbyThomas Osborne, 1st Duke of Leeds

Thomas Osborne, 1st Duke of Leeds, KG , English statesman , served in a variety of offices under Kings Charles II and William III of England.-Early life, 1632–1674:The son of Sir Edward Osborne, Bart., of Kiveton, Yorkshire, Thomas Osborne...

; Osborne was more willing to listen and was introduced to Oates by Tonge.

Privy council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a nation, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the monarch's closest advisors to give confidential advice on...

questioned Oates. On 28 September Oates made 43 allegations against various members of Catholic religious order

Religious order

A religious order is a lineage of communities and organizations of people who live in some way set apart from society in accordance with their specific religious devotion, usually characterized by the principles of its founder's religious practice. The order is composed of initiates and, in some...

s — including 541 Jesuits — and numerous Catholic nobles. He accused Sir George Wakeman

George Wakeman

Sir George Wakeman was an English royal physician to Catherine of Braganza, Consort of Charles II of England. In 1678, he was perjured by Titus Oates, who had gained backing of Thomas Osborne, 1st Earl of Danby, highly placed in government...

, the Queen's

Catherine of Braganza

Catherine of Braganza was a Portuguese infanta and queen consort of England, Scotland and Ireland as the wife of King Charles II.She married the king in 1662...

physician, and Edward Colman

Edward Colman

Edward Colman or Coleman was an English Catholic courtier under Charles II of England. He was hanged, drawn and quartered on a treason charge, having been implicated by Titus Oates in his false accusations concerning a Popish Plot...

, the secretary to Mary of Modena

Mary of Modena

Mary of Modena was Queen consort of England, Scotland and Ireland as the second wife of King James II and VII. A devout Catholic, Mary became, in 1673, the second wife of James, Duke of York, who later succeeded his older brother Charles II as King James II...

who was the Duchess of York

Duchess of York

Duchess of York is the principal courtesy title held by the wife of the Duke of York. The title is gained with marriage alone and is forfeited upon divorce. Four of the twelve Dukes of York did not marry or had already assumed the throne prior to marriage, therefore there have only ever been eleven...

, of planning to assassinate Charles. Although Oates may have selected the names randomly, or with the help of the Earl of Danby, Colman was found to have corresponded with a French Jesuit, which condemned him. Wakeman was later acquitted.

Others Oates accused included Dr William Fogarty, Archbishop Peter Talbot

Archbishop Peter Talbot

Peter Talbot was the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Dublin from 1669 to his death.- Early life :Talbot was born at Malahide, County Dublin, Ireland, in 1620. At an early age he entered the Society of Jesus in Portugal. He was ordained a priest at Rome, and for some years thereafter held the chair...

of Dublin, Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys FRS, MP, JP, was an English naval administrator and Member of Parliament who is now most famous for the diary he kept for a decade while still a relatively young man...

MP

Member of Parliament

A Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

, and Lord Belasyse

John Belasyse, 1st Baron Belasyse

John Belasyse, 1st Baron Belasyse PC was an English nobleman, soldier and Member of Parliament, notable for his role during and after the English Civil War.-Early life:...

. With the help of Danby the list grew to 81 accusations. Oates was given a squad of soldiers and he began to round up Jesuits, including those who had helped him in the past.

On 6 September 1678, Oates and Tonge approached an Anglican magistrate, Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey

Edmund Berry Godfrey

Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey was an English magistrate whose mysterious death caused anti-Catholic uproar in England...

. On 12 October, Godrey disappeared and five days later his dead body was found in a ditch at Primrose Hill

Primrose Hill

Primrose Hill is a hill of located on the north side of Regent's Park in London, England, and also the name for the surrounding district. The hill has a clear view of central London to the south-east, as well as Belsize Park and Hampstead to the north...

; he had been strangled and run through with his own sword. In September Oates and Tonge had sworn an affidavit in front of Godfrey detailing their accusations. Oates exploited this incident to launch a public campaign against the "Papist

Papist

Papist is a term or an anti-Catholic slur, referring to the Roman Catholic Church, its teachings, practices, or adherents. The term was coined during the English Reformation to denote a person whose loyalties were to the Pope, rather than to the Church of England...

s" and alleged that murder of Godfrey had been the work of the Jesuits.

On 24 November 1678, Oates claimed the Queen was working with the King's physician to poison the King, and Oates enlisted the aid of "Captain" William Bedloe

William Bedloe

William Bedloe was an English fraudster and informer, born at Chepstow.He appears to have been well educated; he was certainly clever, and after moving to London in 1670 he became acquainted with some Jesuits and was occasionally employed by them...

, who was ready to say anything for money. The King personally interrogated Oates, caught him out in a number of inaccuracies and lies, and ordered his arrest. However, a few days later, with the threat of a constitutional crisis

Constitutional crisis

A constitutional crisis is a situation that the legal system's constitution or other basic principles of operation appear unable to resolve; it often results in a breakdown in the orderly operation of government...

, Parliament forced the release of Oates, who soon received a state apartment in Whitehall

Whitehall

Whitehall is a road in Westminster, in London, England. It is the main artery running north from Parliament Square, towards Charing Cross at the southern end of Trafalgar Square...

and an annual allowance of £1,200.

Oates was heaped with praise. He asked the College of Arms

College of Arms

The College of Arms, or Heralds’ College, is an office regulating heraldry and granting new armorial bearings for England, Wales and Northern Ireland...

to check his lineage and produce a coat of arms

Coat of arms

A coat of arms is a unique heraldic design on a shield or escutcheon or on a surcoat or tabard used to cover and protect armour and to identify the wearer. Thus the term is often stated as "coat-armour", because it was anciently displayed on the front of a coat of cloth...

for him and subsequently received the arms of a family that had died out. There were even rumours that Oates was to be married to a daughter of the Earl of Shaftsbury.

After nearly three years and the execution of at least 15 innocent men, opinion began to turn against Oates. The last high-profile victim of the climate of suspicion was Oliver Plunkett

Oliver Plunkett

Saint Oliver Plunkett was the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland....

, Archbishop of Armagh, who was executed on 1 July 1681. William Scroggs

William Scroggs

Sir William Scroggs , Lord Chief Justice of England, was the son of an Oxford landowner; an account of him being the son of a butcher of sufficient means to give his son a university education is merely a rumour....

, the Lord Chief Justice of England

Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales

The Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales is the head of the judiciary and President of the Courts of England and Wales. Historically, he was the second-highest judge of the Courts of England and Wales, after the Lord Chancellor, but that changed as a result of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005,...

, began to declare more people innocent, as he had done in the Wakeman trial, and a backlash took place.

Aftermath

On 31 August 1681, Oates was told to leave his apartments in WhitehallWhitehall

Whitehall is a road in Westminster, in London, England. It is the main artery running north from Parliament Square, towards Charing Cross at the southern end of Trafalgar Square...

, but remained undeterred and even denounced the King, the Duke of York, and just about anyone he regarded as an opponent. He was arrested for sedition

Sedition

In law, sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that is deemed by the legal authority to tend toward insurrection against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent to lawful authority. Sedition may include any...

, sentenced to a fine of £100,000 and thrown into prison.

James II of England

James II & VII was King of England and King of Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII, from 6 February 1685. He was the last Catholic monarch to reign over the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland...

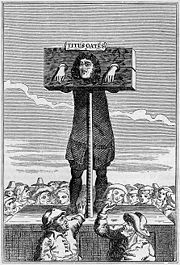

acceded to the throne in 1685, he had Oates retried and sentenced for perjury to be stripped of clerical dress, imprisoned for life and to be pilloried

Pillory

The pillory was a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, formerly used for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse, sometimes lethal...

annually. Oates was taken out of his cell wearing a hat with the text "Titus Oates, convicted upon full evidence of two horrid perjuries" and put into the pillory at the gate of Westminster Hall (now New Palace Yard

New Palace Yard

New Palace Yard is to the northwest of the Houses of Parliament , in Westminster, London, England. It is to the east of Parliament Square, to the west of Big Ben, and to the north of Westminster Hall...

) where passers-by pelted him with eggs. The next day he was pilloried in London and the third day was stripped, tied to a cart, and whipped from Aldgate

Aldgate

Aldgate was the eastern most gateway through London Wall leading from the City of London to Whitechapel and the east end of London. Aldgate gives its name to a ward of the City...

to Newgate

Newgate

Newgate at the west end of Newgate Street was one of the historic seven gates of London Wall round the City of London and one of the six which date back to Roman times. From it a Roman road led west to Silchester...

. The next day, the whipping resumed. The judge

Judge

A judge is a person who presides over court proceedings, either alone or as part of a panel of judges. The powers, functions, method of appointment, discipline, and training of judges vary widely across different jurisdictions. The judge is supposed to conduct the trial impartially and in an open...

was Judge Jeffreys

George Jeffreys, 1st Baron Jeffreys

George Jeffreys, 1st Baron Jeffreys of Wem, PC , also known as "The Hanging Judge", was an English judge. He became notable during the reign of King James II, rising to the position of Lord Chancellor .- Early years and education :Jeffreys was born at the family estate of Acton Hall, near Wrexham,...

who stated that Oates was a "shame to mankind".

Oates spent the next three years in prison. In 1689, upon the accession of William of Orange

William III of England

William III & II was a sovereign Prince of Orange of the House of Orange-Nassau by birth. From 1672 he governed as Stadtholder William III of Orange over Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel of the Dutch Republic. From 1689 he reigned as William III over England and Ireland...

and Mary

Mary II of England

Mary II was joint Sovereign of England, Scotland, and Ireland with her husband and first cousin, William III and II, from 1689 until her death. William and Mary, both Protestants, became king and queen regnant, respectively, following the Glorious Revolution, which resulted in the deposition of...

, he was pardoned and granted a pension of £260 a year, but his reputation did not recover. The pension was later suspended, but in 1698 was restored and increased to £300 a year. Oates died on 12 or 13 July, 1705.