Vio Romano

Encyclopedia

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

sculptor. He was born in Venice

Venice

Venice is a city in northern Italy which is renowned for the beauty of its setting, its architecture and its artworks. It is the capital of the Veneto region...

and taught sculpture there.

Dust continues to gather on the silent mass of plaster casts piled together in Romano Vio's studio on the Lido, next door to the old church of San Nicolò. Romano Vio left us almost a year ago: he went silently, in keeping with his character. I make my way between the plaster casts: some are in fragments, others seem to be waiting for a loving hand to come and bring them back to life. There are some which modestly conceal a distant, unreal and bewitching beauty. I ask myself: is it possible that a sculptor of such calibre must fall into oblivion with the passing of time? That no public body intervenes to bring some order to this confusion? Vio was an exaggeratedly unobtrusive man: wrapped up in his world of work and family affections, he never bothered about any "self-glorification". A veil of sadness comes over me. I remember him on the occasion of his last exhibition in the adjoining cloisters of San Nicolò in October 1982. I stood in admiration before his works; and I put this admiration into words. "I have always worked conscientiously..." he replied softly, gesturing with his arms.

Conscientiousness - that is to say the integrity he had in his work - has always guided him, and we must also give him credit for this in an age when - on the contrary – presumption and exhibitionism are all too often rewarded.

Romano Vio's life (1913–1984) has been dedicated in its entirety to sculpture. His curriculum vitae abounds in commissions, competitions, prizes, exhibitions, without any interruptions except for the war. He had wrapped himself in a sort of golden cocoon in his beloved Venice. He taught at the Accademia; he retired to work in his studio. He respected work in a traditional way: he considered it almost something sacred. He experimented with every kind of technique and material, from marble to cement, but he was particularly fond of working with clay. He had been in Bellotto's school, and then Assistant to Crocetti who held him in high esteem. Many of his works are enormous, starting with the group of bronzes for the Umberto Giordano Monument in Foggia, from the large marble block for Franco Marinotti in Torviscosa to the enormous bronze "Annunciazione" for the church of Altobello in Mestre. No exertion — even physical — frightened him. He was sustained by an unshakeable faith, equalled only by his Franciscan-like modesty.

This publication - in occasion of the exhibition at the San Vidal Art Centre - aims to give prominence to some of his works. Something more than a tribute to a lost master: an incentive to deepen the critics' awareness of him. One consideration seems to emerge immediately; Vio's extraordinary technical ability. Apart from any appraisal of its value, this ability tells us that we are face to face with a sculptor of the old school. His forerunners are naturally enough Trubetskoi, Dal Zotto, Grandi, that is to say those who created the monuments at the time of Italy's Unification. Now that today we are rediscovering late 19th century sculpture with its proud realistic stamp and controversial rhetoric, we cannot but note that at that time the commissions gave sculptors that room to manoeuvre which today is denied them. Vio should have had the opportunity to work on great themes in view of the results achieved when he had been given this type of commission. Arturo Martini himself deeply felt the need to "do things on a large scale" (and his indifference to the political aspects of the themes enforced on him is well-known).

Therefore, Vio was slightly restrained by the changing times, as the contemporary sculptors of his character have been in general. Moreover, he regretted the limited space of his studio on the Lido: he was often obliged to work in the open. He felt it was important to match himself against large dimensions.

This is where the second consideration comes in: that is to say, style. Our age seems to be bound to the fetishism of style which, as we well know, is often reduced to a symbol. Vio has found his own personal way to create. His character, which loathed any kind of constraint, led him each time to follow his inspiration, the emotion of the moment. He wanted to be free. Therefore, we find him turning to different ideas and themes, as I mentioned when I wrote a well-known review for the exhibition at San Nicolò in 1982: from 16th century luminarism to a grotesque and expressionist style, from Renaissance modelling to the most turgid Baroque. This versatility has often been taken for eclecticism. In a certain sense it is: but not as subjection to the so called "mannerisms", but rather as restlessness of mind, the desire for an unceasing search for perfection, wrapped in deep poetics, above all conscious of the continuing need to experiment and, indirectly, to mature. When it came to sculpture, this man, seemingly so gentle, harboured extraordinary energy which each time gave him the capacity to not let himself be swallowed up by easy fashions.

I would say that over the fifty or so year span of his work, there is no lack of inspiration, no repetitiveness. There might have been set-backs, there might have been missed goals, but his spirit always appeared flawless, even youthful I would say. Moreover, right from the beginning Vio rejected the easy appeal of conventionality. In the high relief which won the gold medal in a competition in Genoa in 1935, the large and classically composed masses denote an opening towards the "modernist" style of the thirties and also an extraordinary attention to the new word which Arturo Martini was preaching in Venice and in Italy.

At that time Vio was only twenty-two. Three years later came his "Pugilatore", also showing Martini’s influence in the harmonic modelling of the limbs, but rougher, with a genuinely “Roman” stamp. The same dynamic energy is clear in the boy of the “Passo Romano” which won the prestigious Premio Fadiga in 1939.

As you can see, these beginnings were those of a superb sculptor. Vio immediately began to exhibit at the Biennali; in 1940 he joined the teaching staff of the Accademia in Venice; the following year he was appointed Assistant to Baglioni and won the competition for the obelisk lions in the square at Traù. The war, of course, interrupted his artistic career but in 1946 he returned to the Accademia as Assistant to Crocetti.

It is well-known that the post-war period was a traumatic time for many artists of his generation. The cultural climate changed in the brief space of a couple of years. The Neo-Cubist stylistic elements prevailed; and sculptural abstraction was also imminent. In Venice Arturo Martini left a void and new artists like Alberto Viani began to assert themselves. Vio did not want to conform, and slowly he became cut off even though he continued to be surrounded by great esteem. His works during these years show a simple classical style, in some ways close to that of Crocetti with whom he collaborated several times.

We have the design (c. 1948) for a holy portal with Pope Pius XII; we have the beautiful relief bronze for “Gesù lavoratore” which was awarded a prize in the Pro Civitate Christiana competition in 1955; we have the inspired San Benedetto. They are works of rare purity and feeling. They alternate with moments of greater plastic virtuosity (“Nudo di donna” in 1952, “Dana” in 1954), and also with others of more austere expressiveness, like the magnificent “Testa” exhibited at the Quadriennale in 1951.

His talent came out best of all in commissions for religious works. In 1955 his “Assunta” won a competition in Rome: an exquisite harmony of shapes and drapery in Neo-Settecento style.The following year (1956) his large relief won first prize in Savona in a competition for a Monument to the Resistance: a work in many horizontal sections which shows a clear and successful balance of composition. However, over the years, the artist’s expressive tendency increasingly

emerged; sometimes turned towards a sort of lyrical intimism (his splendid “Simonetta” was exhibited at the Biennale in 1956), sometimes towards ivelier and almost animated forms. This is the case with the complex monument to Umberto Giordano carried out for a competition in Foggia in 1956: a series of lively scenes of extraordinary vivacity which, in certain moments, borders on the grotesque. It is a method of sculpting which has various stylistic influences: Vio knew how to be realist and lyricist, purist and expressionist. There can be no doubt that the skill of his workmanship is extraordinary, even though marked by the great 19th century current.

In another important commission, the one for the Monument to Franco Marinotti in Torviscosa, Vio created a relief which started from a mere line which, as it rose, created clearly defined and compact relief figures, beautifully inserted into the large, marble parallelepiped.

These large works alternated with exquisitely made panels which reveal a gentle and, at the same time, solemn intimism, which could be said to be of 15th century Tuscan quality (like the "Artigiano" in 1957).

Sometimes old themes were re-elaborated (the "Pugilatore" with its splendid plastic

torsion); in other moments the expressionist aspect surfaced again. In the "Fuga in Egitto" (1960), the composition is modelled according to a remarkable archaism of Gothic origin. In "Nostro vessillo" (1969) the theme of the Crucifixion is innervated by an expressive force which heightens the verticality of the theme with even primitive elements.

In other words, the inspiration is always different. Vio closely studied 13th and 14th century sculptures from which he drew perfection of form, as in the charming model for the competition for the "Partigiana" in Venice (certainly far better idealized than Murer's bronze which emerges today on the surface of the water along the Riva dei Sette Martiri).

Neither must we forget his intense work as a portrait sculptor as shown by some examples especially from the sixties. However, as the years passed, it was in religious works that the artist increasingly gained perfection. There are many works and there is no point in recalling them all here one by one. It is sufficient to mention the magnificent bronzes for the church of Fossò, two of his last works: above all the group depicting the three Cardinal Virtues, inserted into an elegant 15th century triple arch, has a grace and elegance of exquisite taste.

Up until the end, despite the weight of years, Vio worked with a sense of unchanged spiritual purity, outside of any movement or fashion. When he was not carrying out large, important works, he was engaged in modelling small terracottas: figurines, nudes, scenes of lively and spontaneous expressiveness. And each time it seemed that inspiration was being born for the first time: such was the freshness which guided his hand,

The impressions gained from this series of works (most of which, unfortunately, in reproductions), only serve to confirm that it is time for a wider and more systematic review of all Romano Vio's work.

Three years ago, after visiting the exhibition in the monastery of San Nicolò, I wrote: "You leave the cloisters with a feeling of peace and serenity". This is my wish to all those who come to see the works by this Venetian master in this posthumous exhibition at San Vidal. Peace and serenity: that is to say the antidotes for the fast-moving and neurotic age in which we live.

Paolo Rizzi 1985]]

.

Timeline

Dust continues to gather on the silent mass of plaster casts piled together in Romano Vio's studio on the Lido, next door to the old church of San Nicolò. Romano Vio left us almost a year ago: he went silently, in keeping with his character. I make my way between the plaster casts: some are in fragments, others seem to be waiting for a loving hand to come and bring them back to life. There are some which modestly conceal a distant, unreal and bewitching beauty. I ask myself: is it possible that a sculptor of such calibre must fall into oblivion with the passing of time? That no public body intervenes to bring some order to this confusion? Vio was an exaggeratedly unobtrusive man: wrapped up in his world of work and family affections, he never bothered about any "self-glorification". A veil of sadness comes over me. I remember him on the occasion of his last exhibition in the adjoining cloisters of San Nicolò in October 1982. I stood in admiration before his works; and I put this admiration into words. "I have always worked conscientiously..." he replied softly, gesturing with his arms.Conscientiousness - that is to say the integrity he had in his work - has always guided him, and we must also give him credit for this in an age when - on the contrary – presumption and exhibitionism are all too often rewarded.

Romano Vio's life (1913–1984) has been dedicated in its entirety to sculpture. His curriculum vitae abounds in commissions, competitions, prizes, exhibitions, without any interruptions except for the war. He had wrapped himself in a sort of golden cocoon in his beloved Venice. He taught at the Accademia; he retired to work in his studio. He respected work in a traditional way: he considered it almost something sacred. He experimented with every kind of technique and material, from marble to cement, but he was particularly fond of working with clay. He had been in Bellotto's school, and then Assistant to Crocetti who held him in high esteem. Many of his works are enormous, starting with the group of bronzes for the Umberto Giordano Monument in Foggia, from the large marble block for Franco Marinotti in Torviscosa to the enormous bronze "Annunciazione" for the church of Altobello in Mestre. No exertion — even physical — frightened him. He was sustained by an unshakeable faith, equalled only by his Franciscan-like modesty.

This publication - in occasion of the exhibition at the San Vidal Art Centre - aims to give prominence to some of his works. Something more than a tribute to a lost master: an incentive to deepen the critics' awareness of him. One consideration seems to emerge immediately; Vio's extraordinary technical ability. Apart from any appraisal of its value, this ability tells us that we are face to face with a sculptor of the old school. His forerunners are naturally enough Trubetskoi, Dal Zotto, Grandi, that is to say those who created the monuments at the time of Italy's Unification. Now that today we are rediscovering late 19th century sculpture with its proud realistic stamp and controversial rhetoric, we cannot but note that at that time the commissions gave sculptors that room to manoeuvre which today is denied them. Vio should have had the opportunity to work on great themes in view of the results achieved when he had been given this type of commission. Arturo Martini himself deeply felt the need to "do things on a large scale" (and his indifference to the political aspects of the themes enforced on him is well-known).

Therefore, Vio was slightly restrained by the changing times, as the contemporary sculptors of his character have been in general. Moreover, he regretted the limited space of his studio on the Lido: he was often obliged to work in the open. He felt it was important to match himself against large dimensions.

This is where the second consideration comes in: that is to say, style. Our age seems to be bound to the fetishism of style which, as we well know, is often reduced to a symbol. Vio has found his own personal way to create. His character, which loathed any kind of constraint, led him each time to follow his inspiration, the emotion of the moment. He wanted to be free. Therefore, we find him turning to different ideas and themes, as I mentioned when I wrote a well-known review for the exhibition at San Nicolò in 1982: from 16th century luminarism to a grotesque and expressionist style, from Renaissance modelling to the most turgid Baroque. This versatility has often been taken for eclecticism. In a certain sense it is: but not as subjection to the so called "mannerisms", but rather as restlessness of mind, the desire for an unceasing search for perfection, wrapped in deep poetics, above all conscious of the continuing need to experiment and, indirectly, to mature. When it came to sculpture, this man, seemingly so gentle, harboured extraordinary energy which each time gave him the capacity to not let himself be swallowed up by easy fashions.

I would say that over the fifty or so year span of his work, there is no lack of inspiration, no repetitiveness. There might have been set-backs, there might have been missed goals, but his spirit always appeared flawless, even youthful I would say. Moreover, right from the beginning Vio rejected the easy appeal of conventionality. In the high relief which won the gold medal in a competition in Genoa in 1935, the large and classically composed masses denote an opening towards the "modernist" style of the thirties and also an extraordinary attention to the new word which Arturo Martini was preaching in Venice and in Italy.

At that time Vio was only twenty-two. Three years later came his "Pugilatore", also showing Martini’s influence in the harmonic modelling of the limbs, but rougher, with a genuinely “Roman” stamp. The same dynamic energy is clear in the boy of the “Passo Romano” which won the prestigious Premio Fadiga in 1939.

As you can see, these beginnings were those of a superb sculptor. Vio immediately began to exhibit at the Biennali; in 1940 he joined the teaching staff of the Accademia in Venice; the following year he was appointed Assistant to Baglioni and won the competition for the obelisk lions in the square at Traù. The war, of course, interrupted his artistic career but in 1946 he returned to the Accademia as Assistant to Crocetti.

It is well-known that the post-war period was a traumatic time for many artists of his generation. The cultural climate changed in the brief space of a couple of years. The Neo-Cubist stylistic elements prevailed; and sculptural abstraction was also imminent. In Venice Arturo Martini left a void and new artists like Alberto Viani began to assert themselves. Vio did not want to conform, and slowly he became cut off even though he continued to be surrounded by great esteem. His works during these years show a simple classical style, in some ways close to that of Crocetti with whom he collaborated several times.

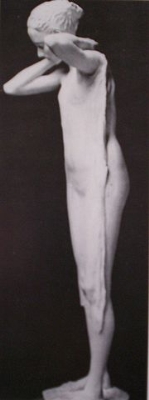

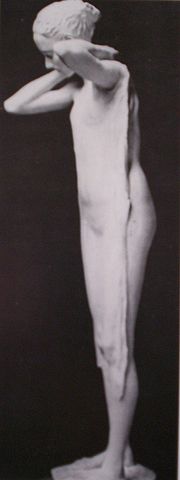

We have the design (c. 1948) for a holy portal with Pope Pius XII; we have the beautiful relief bronze for “Gesù lavoratore” which was awarded a prize in the Pro Civitate Christiana competition in 1955; we have the inspired San Benedetto. They are works of rare purity and feeling. They alternate with moments of greater plastic virtuosity (“Nudo di donna” in 1952, “Dana” in 1954), and also with others of more austere expressiveness, like the magnificent “Testa” exhibited at the Quadriennale in 1951.

Dana 1954 –Galleria d’Arte Moderna – Torino

His talent came out best of all in commissions for religious works. In 1955 his “Assunta” won a competition in Rome: an exquisite harmony of shapes and drapery in Neo-Settecento style.The following year (1956) his large relief won first prize in Savona in a competition for a Monument to the Resistance: a work in many horizontal sections which shows a clear and successful balance of composition. However, over the years, the artist’s expressive tendency increasingly

emerged; sometimes turned towards a sort of lyrical intimism (his splendid “Simonetta” was exhibited at the Biennale in 1956), sometimes towards ivelier and almost animated forms. This is the case with the complex monument to Umberto Giordano carried out for a competition in Foggia in 1956: a series of lively scenes of extraordinary vivacity which, in certain moments, borders on the grotesque. It is a method of sculpting which has various stylistic influences: Vio knew how to be realist and lyricist, purist and expressionist. There can be no doubt that the skill of his workmanship is extraordinary, even though marked by the great 19th century current.

In another important commission, the one for the Monument to Franco Marinotti in Torviscosa, Vio created a relief which started from a mere line which, as it rose, created clearly defined and compact relief figures, beautifully inserted into the large, marble parallelepiped.

These large works alternated with exquisitely made panels which reveal a gentle and, at the same time, solemn intimism, which could be said to be of 15th century Tuscan quality (like the "Artigiano" in 1957).

Sometimes old themes were re-elaborated (the "Pugilatore" with its splendid plastic

torsion); in other moments the expressionist aspect surfaced again. In the "Fuga in Egitto" (1960), the composition is modelled according to a remarkable archaism of Gothic origin. In "Nostro vessillo" (1969) the theme of the Crucifixion is innervated by an expressive force which heightens the verticality of the theme with even primitive elements.

In other words, the inspiration is always different. Vio closely studied 13th and 14th century sculptures from which he drew perfection of form, as in the charming model for the competition for the "Partigiana" in Venice (certainly far better idealized than Murer's bronze which emerges today on the surface of the water along the Riva dei Sette Martiri).

Neither must we forget his intense work as a portrait sculptor as shown by some examples especially from the sixties. However, as the years passed, it was in religious works that the artist increasingly gained perfection. There are many works and there is no point in recalling them all here one by one. It is sufficient to mention the magnificent bronzes for the church of Fossò, two of his last works: above all the group depicting the three Cardinal Virtues, inserted into an elegant 15th century triple arch, has a grace and elegance of exquisite taste.

Up until the end, despite the weight of years, Vio worked with a sense of unchanged spiritual purity, outside of any movement or fashion. When he was not carrying out large, important works, he was engaged in modelling small terracottas: figurines, nudes, scenes of lively and spontaneous expressiveness. And each time it seemed that inspiration was being born for the first time: such was the freshness which guided his hand,

The impressions gained from this series of works (most of which, unfortunately, in reproductions), only serve to confirm that it is time for a wider and more systematic review of all Romano Vio's work.

Three years ago, after visiting the exhibition in the monastery of San Nicolò, I wrote: "You leave the cloisters with a feeling of peace and serenity". This is my wish to all those who come to see the works by this Venetian master in this posthumous exhibition at San Vidal. Peace and serenity: that is to say the antidotes for the fast-moving and neurotic age in which we live.

Paolo Rizzi 1985

- 1931/1935 - Exhibited at the Bevilacqua La Masa Gallery in Venice

- 1932/1936 - Studied and worked with Eugenio Bellotto at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice

- 1934 - Modelled the bust of Luigi Passoni

- 1935 - Awarded Gold Medal at the National Exhibition for Artists and Graduates in Genoa with the high relief “A Mother’s Dream” bought by Venice City Council

- 1937 - Submitted an entry for the Sanremo Prize

- 1938 - Admitted to the XIX Venice BiennaleVenice BiennaleThe Venice Biennale is a major contemporary art exhibition that takes place once every two years in Venice, Italy. The Venice Film Festival is part of it. So too is the Venice Biennale of Architecture, which is held in even years...

with a medal to Guglielmo MarconiGuglielmo MarconiGuglielmo Marconi was an Italian inventor, known as the father of long distance radio transmission and for his development of Marconi's law and a radio telegraph system. Marconi is often credited as the inventor of radio, and indeed he shared the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physics with Karl Ferdinand...

, bought by Milan City Council; The Boxer, portraits, Ploughing, Fisherman - 1939 - Won the “D. Fadiga” prize for sculpture in Venice

- 1940 - Admitted to the XX Venice Biennale; portrait of an old man – 1939/40 sports medal. Appointed to the post of Assistant to Umberto Baglioni at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice

- 1941 - Won the competition for and realised the lions of the obelisk in Piazza del Duomo in TraùTRAUTranscoder and Rate Adaptation Unit, or TRAU, performs transcoding function for speech channels and RA for data channels in the GSM network....

(Dalmatia). Call to arms. Copy from Colleoni, Sansovinian reproductions - 1945 - Returned from war having completed, counting all the various calls to arms, 12 years military service. His war service 1940/43 was recognised in 1956 with the Military Cross

- 1946 - At the end of the war he returned to work and to teaching at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice as Assistant to Venanzo Crocetti

- 1947 - Modelled the bronze statue of St. Anthony for the Church in Camposanpiero; portrait of Francesco

- 1948 - Won First Prize at the “Tempio” exhibition in Padua. “Madonna degli Alpini”, a high relief in stone for Pieve di SoligoPieve di SoligoPieve di Soligo is a town with a population of 12,096 inhabitants. It located at the northern province of Treviso, near the border with the province of Belluno in Veneto, Italy.-Notable people:...

. “L’Ascolto”, bronze - 1949 - Highly commended in the competition for the doors for St. Peter’s in Rome. Sketch in the Vatican GalleriesVatican MuseumsThe Vatican Museums , in Viale Vaticano in Rome, inside the Vatican City, are among the greatest museums in the world, since they display works from the immense collection built up by the Roman Catholic Church throughout the centuries, including some of the most renowned classical sculptures and...

Vatican doors: First Door Siena, on the right: St. Peter, Constantine, Gregory the Great, Foundation of the Basilica, Coronation of Charlemagne, Crusade, Religious Orders, 1300 Jubilee Year; on the left: Leo III, Gregory VII, Nicholas V, Return from Avignon, Discovery of America, Council of Trent, Battle of Lepanto, the new Vatican Basilica, Rafael, Michelangelo, Bernini Second Door Perugia, on the left: Paul III, Pius IV, St. Pius V, Missions, the new religious Orders, three personages; on the right: Paul V, Dogma of the Immaculate Conception, Vatican Council, Pius VII, Pius VIII, Pius IX. Modelled the Holy Spirit Altar and candlesticks for the Pro-civitate Christiana in Assisi. Plaster models of the Doors for Siena Cathedral - 1950 - Took part in the International Exhibition of Sacred Art in Rome with “St. Benedict”

- 1951 - Exhibited at the VI Rome Quadriennale. Admitted to the XXV Venice Biennale

- 1953 - Commended in the “Pinocchio” competition in Collodi. The bronze “Dana” exhibited at the Turin Quadriennale. Won the “Città di Pordenone” First Prize for sculpture. Completed a series of works for the cathedral and for the Church of S. Giuseppe in Cavarzere, Madonna for the bell-tower, Via Crucis. Exhibition of sacred art in Bologna

- 1954 - First Prize with Jesus the Worker in AssisiAssisi- Churches :* The Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi is a World Heritage Site. The Franciscan monastery, il Sacro Convento, and the lower and upper church of St Francis were begun immediately after his canonization in 1228, and completed in 1253...

- 1955- First Prize in the competition for “Our Lady of the Assumption” for the church in Vitinia. First Prize in the competition for the plaque of the Belfiore Martyrs, Venice. Verona Biennale – Portrait of a Girl with Plaits.

- 1956 - Appointed teacher of decorative sculpturing at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice. Won the City of Savona national competition dedicated to the Resistance. Won the national competition for the Monument to the musician Umberto GiordanoUmberto GiordanoUmberto Menotti Maria Giordano was an Italian composer, mainly of operas.He was born in Foggia in Puglia, southern Italy, and studied under Paolo Serrao at the Conservatoire of Naples...

- 1956/1961 - Works completed and placed in the Giordano Park in FoggiaFoggiaFoggia is a city and comune of Apulia, Italy, capital of the province of Foggia. Foggia is the main city of a plain called Tavoliere, also known as the "granary of Italy".-History:...

. Beautiful lady, bronze. Simonetta, bronze, exhibited at the Venice Biennale. Head of a man, bust of a woman in bronze, Woman with a Goose - 1957 - The Sleeping Woman exhibited at the Turin Quadriennale. Second prize in artisanship in Aquila

- 1958 - Shared First Prize at the Biennale of Sacred Art in Bologna with St. Clare Driving Out the Saracens. Flight into Egypt, bas-relief

- 1959 - Won “Montecatini” prize at the International Exhibition in Carrara

- 1960 - Completed the Via Crucis and the Altar for the Bianconi Chapel in Monza

- 1962 - Completed the Monument to Giuseppe Marchetti, the youngest Garibaldian hero, and the plaque to the scientist Olivi for the city of Chioggia

- 1963 - Nominated member of the Accademia Nazionale di San Luca in Rome. Modelled a St. Anthony for Padua

- 1964 - Completed the Monument to the Fallen in Arquà Polesine. Entered competition for the Monument to the Partisan Woman, work now in Cá Pesaro Museum of Modern Art, Venice

- 1965 - The Boxer, bronze, private collection. IX Rome Quadriennale

- 1966 - Christ Rising from the Ruins, Ecce Homo, bronze; Woman in an Armchair, cement

- 1967 - Perugia, altarpiece of panels containing 16 figures

- 1968 - Girl with a Snail, cement

- 1969 - Our Standard, bronze

- 1970 - Figure in cement (Cojazzi private collection). Deposition from the Cross, terracotta. Copy of George Washington for Raleigh State Capital, USA. Annunciation, terracotta. St. Agatha, medallion

- 1971 - Completed in marble the monument to the industrialist Franco Marinotti in TorviscosaTorviscosaTorviscosa is a comune in the Province of Udine in the Italian region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, located about 45 km northwest of Trieste and about 30 km south of Udine...

- 1972 - Juggler with Dog, bronze. Madonna di Fatima Manizales for Columbia. The Four Seasons, 4 female figurines depicting the seasons

- 1973 - Completed the bust of the economist Antonio Santarelli for the city of Aquila now housed in the Library

- 1974 - Maternity, Boy

- 1975 - Woman Seated, Nude. Series of works for USA and Brazil. Portrait of Romiatti, of a girl

- 1976 - Ballerina at rest, Ballerina Tying her Shoe, Lady with Umbrella

- 1978 - Madonna del Carmelo for the CarminiCarminiSanta Maria dei Carmini, also called Santa Maria del Carmelo and commonly known simply as the Carmini, is a small church in the sestiere or neighbourhood of Dorsoduro in Venice, northern Italy. It nestles against the former Scuola Grande di Santa Maria del Carmelo, also known as the Scuola dei...

Church in Venice. Competition and Exhibition of Dantesque Sculpture in Ravenna (exhibiting To Overcome Deceit, The Violent against the Next Man, and a medal) - 1979 - Large-scale bronze statue of “Madonna and Child” for the Church of Altobello in Mestre. Padre Pio in bronze and St. Blaise cast in silver with embossment for Maratea. Series of portraits

- 1980 - Copy of St. James for the church of S. Giacometo in Rialto Venice. Padre Pio, Via Crucis, Font, Paschal candlestick and St. Anthony for Mira Porte

- 1981 - Made Knight of the Republic

- 1982 - Exhibition in the Monastery of S. Nicolờ. Donates to the church of S. Nicolờ a statue of St. Francis which was then cast in bronze at the expense of the parishioners. The Greccio Crib, St. Francis Talking to the Birds, The Canticle of Creatures, Paschal candlestick for the Church of S. Ignazio in Venice Lido

- 1983 - Completed two triptychs (the theological virtues and the three evangelical counsels) and reliquary for the church in Fossờ. Annunciation. The Wait – female figure. Female nude in carved wood in full relief

- 1984 - Works on several pieces for the Rome QuadriennaleRome QuadriennaleThe Rome Quadriennale is a foundation for the promotion of contemporary Italian art....

. Reliquary of the three guardian saints of Padua: St. Anthony, St. Gregory, St. Leopold. Dies on 23 August.

There are many other works that cannot be dated.

There are countless portraits, small bronzes and medals in galleries and private collections in Italy and abroad. There are also numerous works of which only a photographic record remains.

The critics have always been intrigued by his incomparable technical skill and by the poetic pathos of his works, always predisposed to sense or share the sometimes metaphorical lofty meanings that at times interact in many of Vio’s works, inevitably kindling irrepressible intellectual forays.

Vio was neither the first nor the only person to perceive that “classic” is and remains one of the fundamental problems of modern culture, where the artist’s dilemma is to break away from or commit to tradition. Vio was aware of this, continues classicism but has the ability to break away from the logical dualism of reality. He no longer appears interested in the gnoseological content of classic but rather in the human side; therefore Vio is an ethical figurative leading artist and as such forms part of the great Italian tradition, from Donatello to Canova. He has the knowledge to reform that tradition in a difficult and contradictory century to bring us to a unique concept of beauty but he surpasses classic classicism in the sense that art is immune to stylistic pre-conditions. His art becomes a testimony understood as awareness of the value and order of events, sublimely demonstrated in the Giordano works in Foggia.