Yoweri Museveni

Encyclopedia

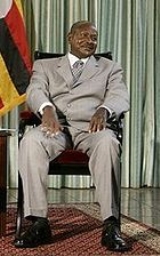

Yoweri Kaguta Museveni (born c. 1939) is a Uganda

n politician and statesman. He has been President of Uganda

since 26 January 1986.

Museveni was involved in the war that deposed Idi Amin Dada

, ending his rule in 1979, and in the rebellion that subsequently led to the demise of the Milton Obote

regime in 1985. With the notable exception of northern areas, Museveni has brought relative stability and economic growth to a country that has endured decades of government mismanagement, rebel activity and civil war

. His tenure has also witnessed one of the most effective national responses to HIV/AIDS in Africa

.

In the mid-to-late 1990s, Museveni was lauded by the West

as part of a new generation of African leaders

. His presidency has been marred, however, by invading and occupying Congo during the Second Congo War

(the war in the Democratic Republic of Congo which has resulted in an estimated 5.4 million deaths since 1998) and other conflicts in the Great Lakes region. Rebellion in the north of Uganda by the Lord's Resistance Army

continues to perpetuate one of the world's worst humanitarian crises. Recent developments, including the abolition of presidential term limits before the 2006 elections and the harassment of democratic opposition, have attracted concern from domestic commentators and the international community.

Born in Ntungamo

Born in Ntungamo

, Uganda Protectorate, Museveni is a member of the Banyankole ethnic group

and his surname, Museveni, means "Son of a man of the Seventh", in honour of the Seventh Battalion of the King's African Rifles

, the British colonial army in which many Ugandans served during World War II

.

Museveni gets his middle name from his father, Amos Kaguta, a cattle herder. Amos Kaguta is also the father of Museveni's brother Caleb Akandwanaho, popularly known in Uganda as "Salim Saleh

", and sister Violet Kajubiri

.

Museveni attended Kyamate Elementary School, Mbarara High School

, and Ntare School

. It was while at high school that he became a born-again Christian. In 1967, he went to the University of Dar es Salaam

in Tanzania

. There, he studied economics

and political science

and became a Marxist

, involving himself in radical pan-African

politics. While at university, he formed the University Students' African Revolutionary Front

activist group and led a student delegation to FRELIMO territory in Portuguese Mozambique

, where he received guerrilla training. Studying under the leftist Walter Rodney

, among others, Museveni wrote a university thesis on the applicability of Frantz Fanon

's ideas on revolutionary violence to post-colonial Africa.

In 1970, Museveni joined the intelligence service

of Ugandan President Dr. Apolo Milton Obote

. When Major General Idi Amin

seized power in a January 1971 military coup

, Museveni fled to Tanzania with other exiles, including the deposed president. The power bases of Amin and Obote were very different, leading to a significant ethnic and regional aspect to the resulting conflict. Obote was from the Lango

ethnic group of the central north, while Amin was a Kakwa

from the northwestern corner of the country. The British colonial government had organized the colony's internal politics so that the Lango and Acholi dominated the national military, while people from southern parts of the country were active in business. This situation endured until the coup, when Amin filled the top positions of government with Kakwa and Lugbara

and violently repressed the Lango and their Acholi allies.

in September 1972 and were repelled, suffering heavy losses. The situation of the rebels was compounded by a peace agreement signed later in the year by Tanzania and Uganda, in which rebels were denied the use of Tanzanian soil for aggression against Uganda. Museveni briefly worked as a lecturer at a co-operative college in Moshi

, in northern Tanzania, before breaking away from the mainstream opposition and forming the Front for National Salvation

(FRONASA) in 1973. In August of the same year, he married Janet Kataha, a former secretary and airline stewardess with whom he would have four children.

In October 1978, Amin ordered the invasion of Tanzania in order to claim the Kagera

province for Uganda. From 24 to 26 March 1979, Museveni and FRONASA attended a gathering of exiles and rebel groups in the northern Tanzanian town of Moshi

. Overcoming ideological differences, for the time being at least, the various groups established the Uganda National Liberation Front

(UNLF). Museveni was appointed to an 11-member Executive Council, chaired by Yusuf Kironde Lule. This was accompanied by a National Consultative Council (NCC) with one member for each of the 28 groups represented at the meeting. The UNLF joined forces with the Tanzanian army to launch a counter-attack which culminated in the toppling of the Amin regime in April 1979. Museveni was named the new Minister of State for Defence in the new UNLF government. He was the youngest minister in Yusuf Lule's administration. The thousands of troops which Museveni recruited into FRONASA during the war were incorporated into the new national army. They retained their loyalty to Museveni, however, and would be crucial in later rebellions against the second Obote regime.

The NCC selected Godfrey Binaisa

as the new chairman of the UNLF after infighting led to the deposition of Yusuf Lule in June 1979. Machinations to consolidate power continued with Binaisa in a similar manner to his predecessor. In November, Museveni was reshuffled from the Ministry of Defence to the Ministry of Regional Cooperation, with Binaisa himself taking over the key defence role. In May 1980, Binaisa himself was placed under house arrest after an attempt to dismiss Oyite Ojok, the army chief of staff – in what was a de facto coup led by Paulo Muwanga

, Yoweri Museveni, Oyite Ojok and Tito Okello

. A Presidential Commission

, with Museveni as Vice-Chairman, was installed and quickly announced plans for a general election in December.

Now a relatively well-known national figure, Museveni established a new political party, the Uganda Patriotic Movement

(UPM), which he would lead in the elections. He would be competing against three other political groupings: the Uganda People's Congress

(UPC), led by former president Milton Obote

; the Conservative Party

(CP); the Democratic Party

(DP). The main contenders were seen to be the UPC and DP. The official results declared UPC the winner with Museveni's UPM gaining only one of the 126 available seats. A number of irregularities compromised the credibility of the poll. In the planning of the election, the leader of the ruling commission, Paulo Muwanga

, supported the UPC's view that each candidate should have a separate ballot box. This was fiercely opposed by the other parties, which maintained that it would make the poll easier to manipulate. The configuration of political boundaries may also have aided the UPC. Constituencies in generally pro-UPC northern Uganda contained proportionally less voters than the anti-UPC Buganda

, giving more power to Obote's party. Suspicions of fraud were compounded by Muwanga's announcement on the day of the election that all results should be cleared by him before they were announced publicly. The losing parties refused to recognise the legitimacy of the new regime, citing widespread electoral irregularities.

(PRA). There they planned a rebellion against the second Obote regime, popularly known as "Obote II", and its armed forces, the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA). The insurgency began with an attack on an army installation in the central Mubende

district on 6 February 1981. The PRA later merged with former president Yusufu Lule's fighting group, the Uganda Freedom Fighters

(UFF), to create the National Resistance Army

(NRA) with its political wing, the National Resistance Movement

(NRM). Two other rebel groups, the Uganda National Rescue Front

(UNRF) and Former Uganda National Army (FUNA), formed in West Nile

from the remnants of Amin's supporters, engaged Obote's forces.

The NRM/A developed a "Ten-point Programme" for an eventual government, covering democracy, security, consolidation of national unity, defending national independence, building an independent, integrated and self-sustaining economy, improvement of social services, elimination of corruption and misuse of power, redressing inequality, cooperation with other African countries and a mixed economy.

By July 1985, Amnesty International

estimated that the Obote regime had been responsible for more than 300,000 civilian deaths across Uganda, although the CIA World Factbook puts the number at over 100,000. The human rights organisation had made several representations to the government to improve its appalling human rights record from 1982. Abuses were particularly conspicuous in an area of central Uganda known as the Luweero Triangle

. Reports from Uganda during this period brought international criticism to the Obote regime and increased support abroad for Museveni's rebel force. Within Uganda, the brutal suppression of the insurgency aligned the Buganda, the most numerous of Uganda's ethnic groups, with the NRA against the UNLA, which was seen as being dominated by northerners, especially the Lango and Acholi. Until his death in 2005, Milton Obote

blamed the Luwero abuses on the NRA.

On 27 July 1985, subfactionalism within the UPC

government led to a successful military coup against Obote by his former army commander, Lieutenant-General Tito Okello

, an Acholi. Museveni and the NRM/A were angry that the revolution for which they had fought for four years had been "hijacked" by the UNLA, which they viewed as having been discredited by gross human rights violations during Obote II. Despite these reservations, however, the NRM/A eventually agreed to peace talks presided over by a Kenya

n delegation headed by President Daniel arap Moi

.

The talks, which lasted from 26 August to 17 December, were notoriously acrimonious and the resultant ceasefire broke down almost immediately. The final agreement, signed in Nairobi

, called for a ceasefire, demilitarisation of Kampala

, integration of the NRA and government forces, and absorption of the NRA leadership into the Military Council. These conditions were never met.

The prospects of a lasting agreement were limited by several factors, including the Kenyan team's lack of an in-depth knowledge of the situation in Uganda and the exclusion of relevant Ugandan and international actors from the talks, inter alia. In the end, Museveni and his allies refused to share power with generals they did not respect, not least while the NRA had the capacity to achieve an outright military victory.

of Zaire

in an attempt to forestall the involvement of Zairean forces in support of Okello's military junta. On 20 January 1986, however, several hundred troops loyal to Idi Amin were accompanied into Ugandan territory by the Zairean military. The forces intervened in the civil conflict following secret training in Zaire and an appeal from Okello ten days previously. Mobutu's support for Okello was a score Museveni would settle years later, ordering Ugandan forces into the conflict which would finally topple the Zairean leader

.

By this stage, however, the NRA had developed an unstoppable momentum. By 22 January, government troops in Kampala had begun to quit their posts en masse as the rebels gained ground from the south and south-west. On the 25th, the Museveni-led faction finally overran the capital. The NRA toppled Okello's government and declared victory the next day.

By this stage, however, the NRA had developed an unstoppable momentum. By 22 January, government troops in Kampala had begun to quit their posts en masse as the rebels gained ground from the south and south-west. On the 25th, the Museveni-led faction finally overran the capital. The NRA toppled Okello's government and declared victory the next day.

Museveni was sworn in as president three days later on 26 January. "This is not a mere change of guard, it is a fundamental change," said Museveni after a ceremony conducted by British-born chief justice Peter Allen. Speaking to crowds of thousands outside the Ugandan parliament, the new president promised a return to democracy and said: "The people of Africa, the people of Uganda, are entitled to a democratic government. It is not a favour from any regime. The sovereign people must be the public, not the government."

regimes in Uganda were characterised by corruption

, factionalism

and an inability to restore order and acquire popular legitimacy. Museveni needed to avoid repeating these mistakes if his new government was not to befall the same fate. The NRM declared a four-year interim government, composing a broader ethnic base than its predecessors. The representatives of the various factions were nevertheless hand-picked by Museveni. The sectarian violence which had overshadowed Uganda's recent history was put forward as a justification for restricting the activities of the political parties and their ethnically distinct supporter bases. The non-party

system did not prohibit political parties, but prevented them from fielding candidates directly in elections. The so-called "Movement" system, which Museveni said claimed the loyalty of every Ugandan, would be a cornerstone in politics for nearly twenty years.

A system of Resistance Councils, directly elected at the parish level, was established to manage local affairs, including the equitable distribution of fixed-price commodities. The election of Resistance Councils representatives was the first direct experience many Ugandans had with democracy after many decades of varying levels of authoritarianism, and the replication of the structure up to the district level has been credited with helping even people at the local level understand the higher-level political structures.

The new government enjoyed widespread international support, and the economy that had been damaged by the civil war began to recover as Museveni initiated economic policies designed to combat key problems such as hyperinflation

and the balance of payments

. Abandoning his Marxist

ideals, Museveni embraced the neoliberal structural adjustments advocated by the World Bank

and the International Monetary Fund

(IMF).

Uganda began participating in an IMF Economic Recovery Program (ERP) in 1987. Its objectives included the restoration of incentives in order to encourage growth, investment, employment and exports; the promotion and diversification of trade with particular emphasis on export promotion; the removal of bureaucratic constraints and divestment from ailing public enterprises so as to enhance sustainable economic growth and development through the private sector; the liberalisation of trade at all levels.

on the Kenya-Uganda border in late 1987. Any closure of borders with Kenya would have been extremely damaging to landlocked Uganda's economy, whose access to the Indian Ocean

via the port at Mombasa

depends upon Kenya.

During their guerrilla war against the government of Milton Obote

, the National Resistance Army recruited anyone who was willing to fight, regardless of nationality. Persecution at the hands of the Obote regime encouraged many Rwandan exiles living in Uganda to join the ranks of the NRA. Several years into the Museveni government, the Ugandan army still had several thousand Rwandans on its payroll. On the night of 30 September 1990, 4,000 Rwandan members of the NRA left their barracks in secrecy, joining other forces to invade Rwanda from Ugandan territory. It transpired that the Rwandese Patriotic Front (RPF) was operating a large membership within the NRA using a clandestine cell structure.

The RPF was a movement of Rwandan exiles opposed to the government of Juvénal Habyarimana

. RPF leaders included Fred Rwigema

and Paul Kagame

, both Rwandan exiles and founder members of the NRM. During the initial stages of the invasion, Museveni and Habyarimana

were both attending a UN summit in the United States. It has been claimed by who? that the date for the RPF mobilisation was set to allow Museveni to distance himself from their actions until it was too late to stop them. The Rwandan army managed to expel the invasion only after extensive reinforcement from Belgium

, France and Zaire

.

Museveni was blamed for complicity in the September 1990 invasion and/or not having control of his army. The RPF melted away into the Virunga Mountains

straddling the Rwanda-Uganda border. The Habyarimana government accused Uganda of allowing the RPF to use its territory as a rear base, responding by shelling Ugandan villages on the border. Uganda is widely believed to have returned fire, which would probably have protected RPF positions. These exchanges forced more than 60,000 from their homes. Despite the negotiation of a security pact, in which both countries agreed to cooperate in maintaining security along their common border, a resurgent RPF had occupied much of the northern territory of Rwanda by 1992.

In April 1994, a plane carrying President Habyarimana of Rwanda and President Cyprien Ntaryamira

of Burundi

was shot down over Kigali

airport. This precipitated the Rwandan genocide

in which an estimated 800,000 people perished. The Rwandan Patriotic Front overran Kigali and took power.

In April 1995, Uganda cut off diplomatic relations with Sudan

In April 1995, Uganda cut off diplomatic relations with Sudan

in protest at Khartoum

's support for the Lord's Resistance Army

(LRA), a rebel group active in northern Uganda. Sudan, in turn, claimed that Uganda was providing support to the Sudan People's Liberation Army

. Both groups were suspected of operating across the porous Uganda-Sudan border. Disputes between Uganda and Sudan date back to at least 1988. Ugandan refugees sought shelter in southern Sudan during the Amin

and Obote II

regimes. After the NRM had come to power in 1986, however, many of these refugees joined the Ugandan rebel groups including the West Nile Bank Front

and later the LRA. For a significant period, the Museveni government viewed Sudan as the most significant threat to Ugandan security.

Although Museveni now headed up a new government in Kampala, the NRM could not project its influence fully across Ugandan territory, finding itself fighting a number of insurgencies. From the beginning of Museveni's presidency, he drew strong support from the Bantu-speaking

south and southwest, where Museveni had his base. Museveni managed to get the Karamojong

, a group of semi-nomad

s in the sparsely populated north-east that had never had a significant political voice, to align with him by offering them a stake in the new government. However, the northern region along the Sudan

ese border proved more troublesome. In the West Nile sub-region

, inhabited by Kakwa and Lugbara (who had previously supported Amin), the UNRF and FUNA rebel groups fought for years until a combination of military offensives and diplomacy pacified the region; the leader of the UNRF, Moses Ali

, gave up his struggle to become Second Deputy Prime Minister. People from the northern parts of the country viewed the rise of a government led by a person from the south with great trepidation. Rebel groups sprang up among the Lango, Acholi and Teso

, though they were overwhelmed by the strength of the NRA except in the far north where the Sudanese border provided a safe haven. The Acholi rebel Uganda People's Democratic Army

(UPDA) failed to dislodge the NRA occupation of Acholiland, leading to the desperate chiliasm

of the Holy Spirit Movement

(HSM). The defeat of both the UPDA and HSM left the rebellion to a group that eventually became known as the Lord's Resistance Army

, which would turn upon the Acholi themselves.

The NRA subsequently earned a reputation for respecting the rights of civilians, – although Museveni later received criticism for using child soldiers

. Undisciplined elements within the NRA's soon tarnished a hard-won reputation for fairness. "When Museveni's men first came they acted very well – we welcomed them," said one villager, "but then they started to arrest people and kill them."

In March 1989, Amnesty International

published a human rights report on Uganda, entitled Uganda, the Human Rights Record 1986–1989. It documented gross human rights violations committed by NRA troops. In one of the most intense phases of the war, between October and December 1988, the NRA forcibly cleared approximately 100,000 people from their homes in and around Gulu town

. Soldiers committed hundreds of extrajudicial executions as they forcibly moved people, burning down homes and granaries

. However, there were few reports of the systematic torture, equivalent to those committed during Amin and Obote's regimes. In its conclusion, the report offered some hope:

of the Democratic Party

, who contested the election as a candidate for the "Inter-party forces coalition", and the upstart candidate, Mohamed Mayanja. Museveni won with a landslide 75.5 per cent of the vote from a turnout of 72.6 per cent of eligible voters. Although international and domestic observers described the vote as valid, both the losing candidates rejected the results. Museveni was sworn in as president for the second time on 12 May 1996.

The main weapon in Museveni's campaign was the restoration of security and economic normality to much of the country. A memorable electoral image produced by his team depicted a pile of skulls in the Luwero Triangle

. This powerful symbolism was not lost on the inhabitants of this region, who had suffered rampant insecurity during the civil war. The other candidates had difficulty matching Museveni's efficacy in communicating his key message. Museveni seemed to have a remarkable ability to relate political messages by using grass-roots language, especially with people from the south. The metaphor of "carrying a grindstone for leadership", referring to an "authoritative individual, bearing the burden of authority", was just one of many imaginative images he created for his campaign. He would often deliver these in the appropriate local colloquial language, demonstrating respect and attempting to transcend tribalistic politics. Museveni's fluency in English

, Luganda

, Runyankole

and Swahili

often helped him forward his message.

Until the prospect of presidential elections, Ssemogerere (Museveni's concurrent political rival) had been a minister in the NRM government. His decision to challenge the record of Museveni and the NRM, rather than claim a stake in Museveni's "movement", was seen as naive opportunism, and regarded as a political error. Ssemogerere's alliance with the UPC

was anathema to the Baganda

, who might otherwise have lent him some support as the leader of the Democratic Party

. Ssemogerere also accused Museveni of being a Rwandan, a statement often repeated by Museveni's opponents because of his birthplace near the Uganda-Rwanda border, and his supposedly Rwandan origins (Museveni claims to be an ethnic Munyankole

, kin to the Banyarwanda

of Rwanda), and his army of being dominated by Rwandans, which included current Rwandan president Paul Kagame

.

In 1997 he introduced free primary education.

The second set of elections were held in 2001. President Museveni beat his rival Kizza Besigye

as he sailed through with 69% of the vote. Dr Besigye had been a close confidant of the president and he was his bush war physician. They however had a fallout shortly before the 2001 elections, when Dr Besigye decided to stand for presidency. The 2001 election campaigns were a heated affair with president Museveni threatening his rival to put him "six feet under".

The election culminated into a petition filed by Dr Besigye at the Supreme Court of Uganda

. The court ruled that the elections were not free and fair but declined to nullify the outcome by a 3:2 majority decision. It was held that the many cases of election malpractice did not however affect the result in a substantial manner. Justices Benjamin Odoki (Chief justice), Alfrerd Karokora, and Joseph Mulenga ruled in favor of the respondents while Justices Aurthur Haggai Oder (RIP) and John Tsekoko ruled in favor of Dr Besigye.

The most recent presidential elections were held in 2006 where again Museveni prevailed over Dr Besigye scoring 59% of the vote. The election petition in this case had more evidence of election malpractice but by a 4:3 decision, the result was upheld. As before, the judges ruled as they ruled in the 2001 petition. The additional two judges were Justice George W. Kanyeihamba ruling in favor of Dr Besigye and Justice Bart Katureebe in favor of President Museveni and the electoral commission. Dr Besigye predicted that that could be the last presidential election petition filed in the then constituted Supreme court.

Structural adjustment

programs, i.e. privatising state enterprises, cutting government spending and urging African self-reliance. Museveni was elected chairperson of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1991 and 1992. He permitted a free atmosphere within which the news media could operate, and private FM radio stations flourished during the late 1990s. Perhaps Museveni's most widely noted accomplishment has been his government's successful campaign against AIDS

. During the 1980s, Uganda had one of the highest rates of HIV

infection in the world, but now Uganda's rates are comparatively low, and the country stands as a rare success story in the global battle against the virus (see AIDS in Africa). One of the campaigns headed by Museveni to fight against AIDS was the ABC program. The ABC program had three main parts "Abstain, Be faithful, or use Condoms if A and B are not practiced. In April 1998, Uganda became the first country to be declared eligible for debt relief

under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries

(HIPC) initiative, receiving some US$700 million in aid. Museveni was lauded for his affirmative action program for women in the country, he was served by a female vice-president, Specioza Kazibwe

, for nearly a decade, and has done much to encourage women to go to college. On the other hand, Museveni has resisted calls for greater women's family land rights (the right of women to own a share of their matrimonial homes).

From the mid-1990s, Museveni was seen to exemplify a new breed of African leadership

, the antithesis of the "big men" who had dominated politics in the continent since independence. This section from a New York Times article in 1997 is illustrative of the high esteem in which Museveni was held by the western media, governments and academics:

In official briefing papers from Madeleine Albright

's December 1997 Africa tour as Secretary of State

, Museveni was called a "beacon of hope" who runs a "uni-party democracy," despite Uganda not permitting multiparty politics.

n Tutsi

immigrants – who comprised a significant numbers of NRA fighters. The Uganda-based Tutsi-dominated Rwandese Patriotic Front rebel group were close allies of the NRA, and once Museveni had solidified his hold on central power, he lent his support to their cause. Unsuccessful attacks were launched by the RPF against the Hutu government of Rwanda in the first half of the 1990s from bases in southwest Uganda. It was not until the Rwandan Genocide

of 1994 that the RPF took power and its head, Paul Kagame

(a former soldier in Museveni's army), became president.

Following the Rwandan Genocide, the new Rwandan government felt threatened by the presence (across the Rwandan border in Congo

- known then as Zaïre) of former Rwandan soldiers and members of the previous regime. These soldiers were aided by Mobutu Sese Seko

– leading Rwanda (with the aid of Museveni) and Laurent Kabila's rebels to overthrow him and take power in Congo. (see main article: First Congo War

).

In August 1998, Rwanda and Uganda undertook to invade Congo again, this time to overthrow Museveni and Kagame's former ally - Kabila (see main article: Second Congo War

). Museveni and a few close military advisers alone made the decision to send the UPDF

into Congo. A number of highly placed sources indicate that the Ugandan parliament and civilian advisers were not consulted over the matter, as is required by the 1995 constitution. Museveni apparently persuaded an initially reluctant High Command to go along with the venture. "We felt that the Rwandese started the war and it was their duty to go ahead and finish the job, but our President took time and convinced us that we had a stake in what is going on in Congo", one senior officer is reported as saying. The official reasons Uganda gave for the intervention were to stop a "genocide" against the Banyamulenge in DRC in concert with Rwandan forces, and that Kabila had failed to provide security along the border and was allowing the Allied Democratic Forces

(ADF) to attack Uganda from rear bases in DRC. In reality, the UPDF were not deployed in the border region but more than 1,000 kilometres (over 600 miles) to the west of Uganda's frontier with Congo and in support of the Mouvement de Libération du Congo (MLC) rebels seeking to overthrow Kabila. As such, they were unable to prevent the ADF from invading the major town of Fort Portal

and taking over a prison in Western Uganda.

Troops from Rwanda and Uganda plundered the country's rich mineral deposits and timber

. The United States responded to the invasion by suspending all military aid to Uganda, a disappointment to the Clinton administration, which had hoped to make Uganda the centrepiece of the African Crisis Response Initiative. In 2000, Rwandan and Ugandan troops exchanged fire on three occasions in the Congolese city of Kisangani

, leading to tensions and a deterioration in relations between Kagame and Museveni. The Ugandan government has also been criticised for aggravating the Ituri conflict

, a sub-conflict of the Second Congo War

. In December 2005, the International Court of Justice

ruled that Uganda must pay compensation to the Democratic Republic of the Congo for human rights violations during the Second Congo War.

In the north, Uganda had supported Sudan People's Liberation Army

(SPLA) in the Second Sudanese Civil War

against the government in Khartoum

even before Museveni's rise. The continued support for the SPLA, led by Museveni's old acquaintance John Garang

, led Sudan to support the Lord's Resistance Army

(LRA) and other anti-Museveni rebel groups in the mid-1990s. The resulting insecurity and conflicts have caused widespread human displacement

, death and destruction in southern Sudan and northern Uganda. Subsequent warming of relations with Sudan led to a pledge to stop supporting hostile proxy forces (from both sides) and the granting of approval to the UPDF to attack the LRA within Sudan itself.

as the only real challenger. In a populist publicity stunt, a pentagenarian Museveni travelled on a bodaboda motorcycle taxi to submit his nomination form for the election. Bodaboda is a cheap and somewhat dangerous (by western standards) method of transporting passengers around towns and villages in East Africa.

There was much recrimination and bitterness during the 2001 presidential elections campaign, and incidents of violence occurred following the announcement of the results – which were won by Museveni. Besigye challenged the election results in the Supreme Court of Uganda

. Two of the five judges concluded that there were such illegalities in the elections, and that the results should be rejected. The other three judges decided that the illegalities did not affect the result of the election in a substantial manner, but stated that "there was evidence that in a significant number of polling station

s there was cheating" and that in some areas of the country, "the principle of free and fair election was compromised." Besigye was briefly detained and questioned by the police, allegedly in connection with the offense of treason. In September he fled to the USA claiming his life was in danger.

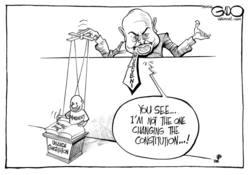

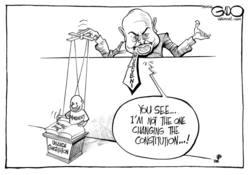

After the elections, political forces allied to Museveni began a campaign to loosen constitutional limits on the presidential term, allowing him to stand for election again in 2006. The 1995 Ugandan constitution provided for a two-term limit on the tenure of the president. Given Uganda's history of dictatorial regimes, this check and balance was designed to prevent a dangerous centralisation of power around a long-serving leader. This period witnessed the removal of key and influential Museveni supporters from his administration, including his childhood friend Eriya Kategaya

After the elections, political forces allied to Museveni began a campaign to loosen constitutional limits on the presidential term, allowing him to stand for election again in 2006. The 1995 Ugandan constitution provided for a two-term limit on the tenure of the president. Given Uganda's history of dictatorial regimes, this check and balance was designed to prevent a dangerous centralisation of power around a long-serving leader. This period witnessed the removal of key and influential Museveni supporters from his administration, including his childhood friend Eriya Kategaya

and cabinet minister Jaberi Bidandi Ssali.

Moves to alter the constitution and alleged attempts to suppress opposition political forces have attracted criticism from domestic commentators, the international community and Uganda's aid donors. In a press release, the main opposition party, the Forum for Democratic Change

(FDC), accused Museveni of engaging in a "life presidency project", and for bribing members of parliament to vote against constitutional amendments, FDC leaders claimed:

As observed by some political commentators, including Wafula Oguttu, Museveni had previously stated that he considered the idea of clinging to office for "15 or more" years ill-advised. Comments by the Irish anti-poverty campaigner Bob Geldof

sparked a protest by Museveni supporters outside the British High Commission in Kampala

. "Get a grip Museveni. Your time is up, go away," said the former rock star in March 2005, explaining that moves to change the constitution were compromising Museveni's record against fighting poverty and HIV/AIDS. In an opinion article in the Boston Globe and in a speech delivered at the Wilson Center, former U.S. Ambassador to Uganda Johnnie Carson heaped more criticism on Museveni. Despite recognising the president as a "genuine reformer" whose "leadership [has] led to stability and growth", Carson also said, "we may be looking at another Mugabe

and Zimbabwe

in the making". "Many observers see Museveni's efforts to amend the constitution as a re-run of a common problem that afflicts many African leaders – an unwillingness to follow constitutional norms and give up power".

In July 2005, Norway

In July 2005, Norway

became the third European country in as many months to announce symbolic cutbacks in foreign aid to Uganda in response to political leadership in the country. The UK and Ireland made similar moves in May. "Our foreign ministry wanted to highlight two issues: the changing of the constitution to lift term limits, and problems with opening the political space, human rights and corruption", said Norwegian Ambassador Tore Gjos. Of particular significance was the arrest of two opposition MPs from the Forum for Democratic Change

. Human rights campaigners charged that the arrests were politically motivated. Human Rights Watch

stated that "the arrest of these opposition MPs smacks of political opportunism". A confidential World Bank

report leaked in May suggested that the international lender might cut its support to non-humanitarian programmes in the Uganda. "We regret that we cannot be more positive about the present political situation in Uganda, especially given the country's admirable record through the late 1990s", said the paper. "The Government has largely failed to integrate the country's diverse peoples into a single political process that is viable over the long term...Perhaps most significant, the political trend-lines, as a result of the President's apparent determination to press for a third term, point downward."

Museveni responded to the mounting international pressure by accusing donors of interfering with domestic politics and using aid to manipulate poor countries. "Let the partners give advice and leave it to the country to decide ... [developed] countries must get out of the habit of trying to use aid to dictate the management of our countries." "The problem with those people is not the third term or fighting corruption or multipartism," added Museveni at a meeting with other African leaders, "the problem is that they want to keep us there without growing.".

In July 2005, a constitutional referendum

In July 2005, a constitutional referendum

lifted a 19-year restriction on the activities of political parties

. In the non-party "Movement system

" (so called "the movement") instituted by Museveni in 1986, parties continued to exist, but candidates were required to stand for election as individuals rather than representative of any political grouping. This measure was ostensibly designed to reduce ethnic divisions, although many observers have subsequently claimed that the system had become nothing more than a restriction on opposition activity. Prior to the vote, the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) spokesperson stated "Key sectors of the economy are headed by people from the president's home area... We have got the most sectarian regime in the history of the country in spite the fact that there are no parties." Many Ugandans saw Museveni's conversion to political pluralism as a concession to donors – aimed at softening the blow when he announces he wants to stay on for a third term. Opposition MP Omara Atubo

has said Museveni's desire for change was merely "a facade behind which he is trying to hide ambitions to rule for life".

was killed when the Ugandan presidential helicopter crashed while he was travelling to Sudan from talks in Uganda. The incident was acutely embarrassing for the Ugandan government and a personal blow for Museveni – Garang had been a political ally since their days together at university. Garang had only been Sudanese vice-president for a matter of weeks before his death, which damaged hopes of a regional order based on a Uganda-South Sudan

alliance.

Widespread speculation as to the cause of the crash led Museveni, on 10 August, to threaten the closure of media outlets which published "conspiracy theories" about Garang's death. In a statement, Museveni claimed such speculation was a threat to national security. "I will no longer tolerate a newspaper which is like a vulture. Any newspaper that plays around with regional security, I will not tolerate it – I will close it." The following day, popular radio station KFM had its license withdrawn for broadcasting a debate on Garang's death. Radio presenter Andrew Mwenda

was eventually arrested for sedition

in connection with comments made on his KFM talk show.

. His candidacy for a further third term sparked criticism, as he had promised in 2001 that he was contesting for the last term. The arrest of the main opposition leader Kizza Besigye

on 14 November – charged with treason, concealment of treason and rape – sparked demonstrations and riots in Kampala and other towns. Museveni's bid for a third term, the arrest of Besigye, and the besiegement of the High Court during a hearing of Besigye's case (by a heavily armed Military Intelligence (CMI) group dubbed by the press as "Black Mambas Urban Hit Squad"), led Sweden

, the Netherlands

and the United Kingdom to withhold economic support to Museveni's government due to concerns about the country's democratic development. On 2 January 2006 Besigye was released after the High Court ordered his immediate release.

The 23 February 2006 elections were Uganda's first multi-party elections in 25 years, and was seen as a test of its democratic credentials. Although Museveni did less well than in the previous election, he was elected for another five-year tenure, having won 59% of the vote against Besigye's 37%. Besigye, who alleged fraud, rejected the result. The Supreme Court of Uganda later ruled that the election was marred by intimidation, violence, voter disenfranchisement, and other irregularities. However, the Court voted 4-3 to uphold the results of the election.

peacekeeping operation in Somalia

.

Another significant issue in Museveni's third term is his decision to open the Mabira Forest

to sugarcane planting. While Museveni argues that new plantations are important for Uganda's economic development

, environmental activists worry about the loss of ecosystems and biodiversity

that will result. This suggestion led to a riot in 2007 that claimed two lives.

Also In this term Museveni held meetings with investors that included Wisdek, to promote Uganda's call centre and outsourcing industry and create employment to the country.

(also known as "The Family"). Sharlet reports that Douglas Coe, leader of The Fellowship, identified Museveni as the organization's "key man in Africa." Further international scrutiny accompanied the 2009 Ugandan efforts to institute the death penalty for homosexuality, with leaders from Canada, the UK, the US, and France expressing concerns for human rights. British newspaper, The Guardian

, reported that President Museveni "appeared to add his backing" to the legislative effort by, among other things, claiming "European homosexuals are recruiting in Africa", and saying gay relationships were against God's will. The 2009 effort for harsher penalties for homosexual behavior further strengthens existing laws

criminalizing homosexuality.

Academic papers

Interviews

Uganda

Uganda , officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. Uganda is also known as the "Pearl of Africa". It is bordered on the east by Kenya, on the north by South Sudan, on the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, on the southwest by Rwanda, and on the south by...

n politician and statesman. He has been President of Uganda

President of Uganda

-List of Presidents of Uganda:-Affiliations:-See also:*Uganda*Vice President of Uganda*Prime Minister of Uganda*Politics of Uganda*History of Uganda*Political parties of Uganda...

since 26 January 1986.

Museveni was involved in the war that deposed Idi Amin Dada

Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada was a military leader and President of Uganda from 1971 to 1979. Amin joined the British colonial regiment, the King's African Rifles in 1946. Eventually he held the rank of Major General in the post-colonial Ugandan Army and became its Commander before seizing power in the military...

, ending his rule in 1979, and in the rebellion that subsequently led to the demise of the Milton Obote

Milton Obote

Apolo Milton Obote , Prime Minister of Uganda from 1962 to 1966 and President of Uganda from 1966 to 1971, then again from 1980 to 1985. He was a Ugandan political leader who led Uganda towards independence from the British colonial administration in 1962.He was overthrown by Idi Amin in 1971, but...

regime in 1985. With the notable exception of northern areas, Museveni has brought relative stability and economic growth to a country that has endured decades of government mismanagement, rebel activity and civil war

Civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same nation state or republic, or, less commonly, between two countries created from a formerly-united nation state....

. His tenure has also witnessed one of the most effective national responses to HIV/AIDS in Africa

HIV/AIDS in Africa

HIV/AIDS is a major public health concern and cause of death in Africa. Although Africa is home to about 14.5% of the world's population, it is estimated to be home to 67% of all people living with HIV and to 72% of all AIDS deaths in 2009.-Overview:...

.

In the mid-to-late 1990s, Museveni was lauded by the West

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West and the Occident , is a term referring to the countries of Western Europe , the countries of the Americas, as well all countries of Northern and Central Europe, Australia and New Zealand...

as part of a new generation of African leaders

New generation of African leaders

The term "new generation" or "new breed" of African leaders was a buzzword widely used in the mid-late 1990s to express optimism in a new generation of African leadership. It has since fallen out of favor, along with several of the leaders....

. His presidency has been marred, however, by invading and occupying Congo during the Second Congo War

Second Congo War

The Second Congo War, also known as Coltan War and the Great War of Africa, began in August 1998 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo , and officially ended in July 2003 when the Transitional Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo took power; however, hostilities continue to this...

(the war in the Democratic Republic of Congo which has resulted in an estimated 5.4 million deaths since 1998) and other conflicts in the Great Lakes region. Rebellion in the north of Uganda by the Lord's Resistance Army

Lord's Resistance Army

The Lord's Resistance Army insurgency is an ongoing guerrilla campaign waged since 1987 by the Lord's Resistance Army rebel group, operating mainly in northern Uganda, but also in South Sudan and eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo...

continues to perpetuate one of the world's worst humanitarian crises. Recent developments, including the abolition of presidential term limits before the 2006 elections and the harassment of democratic opposition, have attracted concern from domestic commentators and the international community.

Early life and career (1944–1972)

Ntungamo

Ntungamo is a town in Western Uganda. It is the largest town in Ntungamo District and the district headquarters are located there. The district is named after the town.-Location:...

, Uganda Protectorate, Museveni is a member of the Banyankole ethnic group

Ethnic group

An ethnic group is a group of people whose members identify with each other, through a common heritage, often consisting of a common language, a common culture and/or an ideology that stresses common ancestry or endogamy...

and his surname, Museveni, means "Son of a man of the Seventh", in honour of the Seventh Battalion of the King's African Rifles

King's African Rifles

The King's African Rifles was a multi-battalion British colonial regiment raised from the various British possessions in East Africa from 1902 until independence in the 1960s. It performed both military and internal security functions within the East African colonies as well as external service as...

, the British colonial army in which many Ugandans served during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

.

Museveni gets his middle name from his father, Amos Kaguta, a cattle herder. Amos Kaguta is also the father of Museveni's brother Caleb Akandwanaho, popularly known in Uganda as "Salim Saleh

Salim Saleh

General Salim Saleh , is an adviser to the President of Uganda on military matters. Formerly, he was the Ugandan Minister of State for Microfinance. Before that, he was a high ranking military official of UPDF, the armed forces of Uganda. He is a brother of the current President of Uganda, Yoweri...

", and sister Violet Kajubiri

Violet Kajubiri

Dr. Violet Kajubiri Froelich served as the General Secretary of the Wildlife Clubs of Uganda. She is also the sister of Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni.-References:...

.

Museveni attended Kyamate Elementary School, Mbarara High School

Mbarara High School

Mbarara High School , is a boys-only boarding middle and high school located in the city of Mbarara, in Mbarara District in Western Uganda.-Location:...

, and Ntare School

Ntare School

Ntare School is a residential boys' secondary school located in Mbarara, Mbarara District, western Uganda. It was founded in 1956 by a Scottish educator named William Crichton....

. It was while at high school that he became a born-again Christian. In 1967, he went to the University of Dar es Salaam

University of Dar es Salaam

The University of Dar es Salaam is a university in the Tanzanian city of Dar es Salaam. The university was born out of a decision taken in 1970 to split the then University of East Africa into three independent universities; Makerere University , University of Nairobi and University of Dar es...

in Tanzania

Tanzania

The United Republic of Tanzania is a country in East Africa bordered by Kenya and Uganda to the north, Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west, and Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique to the south. The country's eastern borders lie on the Indian Ocean.Tanzania is a state...

. There, he studied economics

Economics

Economics is the social science that analyzes the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. The term economics comes from the Ancient Greek from + , hence "rules of the house"...

and political science

Political science

Political Science is a social science discipline concerned with the study of the state, government and politics. Aristotle defined it as the study of the state. It deals extensively with the theory and practice of politics, and the analysis of political systems and political behavior...

and became a Marxist

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

, involving himself in radical pan-African

Pan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism is a movement that seeks to unify African people or people living in Africa, into a "one African community". Differing types of Pan-Africanism seek different levels of economic, racial, social, or political unity...

politics. While at university, he formed the University Students' African Revolutionary Front

University Students' African Revolutionary Front

The University Students' African Revolutionary Front was a political student group formed in 1967 at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. The group, which engaged in study and activism and held regular meetings on Sundays, featured many students who would go on to become influential...

activist group and led a student delegation to FRELIMO territory in Portuguese Mozambique

Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique , is a country in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west and Swaziland and South Africa to the southwest...

, where he received guerrilla training. Studying under the leftist Walter Rodney

Walter Rodney

Walter Rodney was a prominent Guyanese historian and political activist, who was assassinated in Guyana in 1980.-Career:...

, among others, Museveni wrote a university thesis on the applicability of Frantz Fanon

Frantz Fanon

Frantz Fanon was a Martiniquo-Algerian psychiatrist, philosopher, revolutionary and writer whose work is influential in the fields of post-colonial studies, critical theory and Marxism...

's ideas on revolutionary violence to post-colonial Africa.

In 1970, Museveni joined the intelligence service

Military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that exploits a number of information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to commanders in support of their decisions....

of Ugandan President Dr. Apolo Milton Obote

Milton Obote

Apolo Milton Obote , Prime Minister of Uganda from 1962 to 1966 and President of Uganda from 1966 to 1971, then again from 1980 to 1985. He was a Ugandan political leader who led Uganda towards independence from the British colonial administration in 1962.He was overthrown by Idi Amin in 1971, but...

. When Major General Idi Amin

Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada was a military leader and President of Uganda from 1971 to 1979. Amin joined the British colonial regiment, the King's African Rifles in 1946. Eventually he held the rank of Major General in the post-colonial Ugandan Army and became its Commander before seizing power in the military...

seized power in a January 1971 military coup

1971 Ugandan coup d'état

The 1971 Ugandan coup d'état was a military coup d'état executed by the Ugandan military, led by General Idi Amin, against the government of President Milton Obote on January 25, 1971...

, Museveni fled to Tanzania with other exiles, including the deposed president. The power bases of Amin and Obote were very different, leading to a significant ethnic and regional aspect to the resulting conflict. Obote was from the Lango

Lango

-Lango of Uganda:The Lango or Jo Lango live in the Lango sub-region , north of Lake Kyoga. Lango sub-region comprises the districts of Amolatar, Alebtong, Apac, Dokolo, Kole, Lira, Oyam, and Otuke...

ethnic group of the central north, while Amin was a Kakwa

Kakwa

The Kakwa are an ethnic group in northwestern Uganda, South Sudan, and northeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, from Nilotic origin. They are part of Karo people which also includes Bari, Pojulu Mundari, Kuku and Nyangwara. Their language is also called Kutuk na Kakwa , itself an...

from the northwestern corner of the country. The British colonial government had organized the colony's internal politics so that the Lango and Acholi dominated the national military, while people from southern parts of the country were active in business. This situation endured until the coup, when Amin filled the top positions of government with Kakwa and Lugbara

Lugbara

The Lugbara are an ethnic group who live mainly in the West Nile region of Uganda and in the adjoining area of the Democratic Republic of the Congo...

and violently repressed the Lango and their Acholi allies.

FRONASA and the toppling of Amin (1972–80)

The exile forces opposed to Idi Amin, who were predominantly Lango and Acholi, invaded Uganda from TanzaniaTanzania

The United Republic of Tanzania is a country in East Africa bordered by Kenya and Uganda to the north, Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west, and Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique to the south. The country's eastern borders lie on the Indian Ocean.Tanzania is a state...

in September 1972 and were repelled, suffering heavy losses. The situation of the rebels was compounded by a peace agreement signed later in the year by Tanzania and Uganda, in which rebels were denied the use of Tanzanian soil for aggression against Uganda. Museveni briefly worked as a lecturer at a co-operative college in Moshi

Moshi

Moshi is a Tanzanian town with a population of 144,739 in Kilimanjaro Region. The town is situated on the lower slopes of Mt Kilimanjaro, a volcanic mountain that is the highest mountain in Africa....

, in northern Tanzania, before breaking away from the mainstream opposition and forming the Front for National Salvation

Front for National Salvation

The Front for National Salvation was a Ugandan rebel group formed by Yoweri Museveni in 1972. Kikosi Maalum and FRONASA, as well as several smaller groups including Save Uganda Movement and Uganda Freedom Union, formed the Uganda National Liberation Front and its military wing the Uganda...

(FRONASA) in 1973. In August of the same year, he married Janet Kataha, a former secretary and airline stewardess with whom he would have four children.

In October 1978, Amin ordered the invasion of Tanzania in order to claim the Kagera

Kagera Region

Kagera Region is located in the northwestern corner of Tanzania. Bukoba, Kagera Region's capital, is a fast growing town situated on the shore of Lake Victoria. Bukoba lies only 1 degree south of the Equator and is Tanzania's second largest port on the lake. The region neighbors Uganda, Rwanda and...

province for Uganda. From 24 to 26 March 1979, Museveni and FRONASA attended a gathering of exiles and rebel groups in the northern Tanzanian town of Moshi

Moshi

Moshi is a Tanzanian town with a population of 144,739 in Kilimanjaro Region. The town is situated on the lower slopes of Mt Kilimanjaro, a volcanic mountain that is the highest mountain in Africa....

. Overcoming ideological differences, for the time being at least, the various groups established the Uganda National Liberation Front

Uganda National Liberation Front

The Uganda National Liberation Front was a political group formed by exiled Ugandans opposed to the rule of Idi Amin with an accompanying military wing, the Uganda National Liberation Army . UNLA fought alongside Tanzanian forces in the Uganda-Tanzania War that led to the overthrow of Idi Amin's...

(UNLF). Museveni was appointed to an 11-member Executive Council, chaired by Yusuf Kironde Lule. This was accompanied by a National Consultative Council (NCC) with one member for each of the 28 groups represented at the meeting. The UNLF joined forces with the Tanzanian army to launch a counter-attack which culminated in the toppling of the Amin regime in April 1979. Museveni was named the new Minister of State for Defence in the new UNLF government. He was the youngest minister in Yusuf Lule's administration. The thousands of troops which Museveni recruited into FRONASA during the war were incorporated into the new national army. They retained their loyalty to Museveni, however, and would be crucial in later rebellions against the second Obote regime.

The NCC selected Godfrey Binaisa

Godfrey Binaisa

Godfrey Lukongwa Binaisa QC was a Ugandan lawyer who was Attorney General of Uganda from 1962 to 1968 and later served as President of Uganda from June 1979 to May 1980. At his death he was Uganda's only surviving former president....

as the new chairman of the UNLF after infighting led to the deposition of Yusuf Lule in June 1979. Machinations to consolidate power continued with Binaisa in a similar manner to his predecessor. In November, Museveni was reshuffled from the Ministry of Defence to the Ministry of Regional Cooperation, with Binaisa himself taking over the key defence role. In May 1980, Binaisa himself was placed under house arrest after an attempt to dismiss Oyite Ojok, the army chief of staff – in what was a de facto coup led by Paulo Muwanga

Paulo Muwanga

Paulo Muwanga was the chairman of the governing Military Commission, and the de-facto President of Uganda for a few days in May 1980 until the establishment of the Presidential Commission of Uganda. The Presidential Commission, with Muwanga as chairman, held the office of President of Uganda...

, Yoweri Museveni, Oyite Ojok and Tito Okello

Tito Okello

General Tito Lutwa Okello , was a Ugandan Military officer and politician. He was the President of Uganda from 29 July 1985 until 26 January 1986.-Background:Tito Okello was born in 1914 in Kitgum District...

. A Presidential Commission

Presidential Commission of Uganda

The Presidential Commission of Uganda held the office of President of Uganda between 22 May and 15 December 1980. It was composed as follows:* Saulo Musoke* Polycarp Nyamuchoncho* Yoweri Hunter Wacha-Olwol-See also:*Uganda...

, with Museveni as Vice-Chairman, was installed and quickly announced plans for a general election in December.

Now a relatively well-known national figure, Museveni established a new political party, the Uganda Patriotic Movement

Uganda Patriotic Movement

The Uganda Patriotic Movement is a defunct political party in Uganda. It was founded by Yoweri Museveni and participated in the December 1980 general elections, which were won by Milton Obote's Uganda People's Congress...

(UPM), which he would lead in the elections. He would be competing against three other political groupings: the Uganda People's Congress

Uganda People's Congress

The Uganda People's Congress is a political party in Uganda.Uganda People's Congress was founded in 1960 by Milton Obote, who led the country to Independence and later served two presidential terms under the party's banner...

(UPC), led by former president Milton Obote

Milton Obote

Apolo Milton Obote , Prime Minister of Uganda from 1962 to 1966 and President of Uganda from 1966 to 1971, then again from 1980 to 1985. He was a Ugandan political leader who led Uganda towards independence from the British colonial administration in 1962.He was overthrown by Idi Amin in 1971, but...

; the Conservative Party

Conservative Party (Uganda)

The Conservative Party is a political party in Uganda. It is led by Ken Lukyamuzi.In the general election of 23 February 2006, the party won 1 out of 289 elected seats....

(CP); the Democratic Party

Democratic Party (Uganda)

The Democratic Party is a moderate conservative political party in Uganda currently led by Norbert Mao. DP was led by Paul Ssemogerere for 25 years until his retirement in November 2005...

(DP). The main contenders were seen to be the UPC and DP. The official results declared UPC the winner with Museveni's UPM gaining only one of the 126 available seats. A number of irregularities compromised the credibility of the poll. In the planning of the election, the leader of the ruling commission, Paulo Muwanga

Paulo Muwanga

Paulo Muwanga was the chairman of the governing Military Commission, and the de-facto President of Uganda for a few days in May 1980 until the establishment of the Presidential Commission of Uganda. The Presidential Commission, with Muwanga as chairman, held the office of President of Uganda...

, supported the UPC's view that each candidate should have a separate ballot box. This was fiercely opposed by the other parties, which maintained that it would make the poll easier to manipulate. The configuration of political boundaries may also have aided the UPC. Constituencies in generally pro-UPC northern Uganda contained proportionally less voters than the anti-UPC Buganda

Buganda

Buganda is a subnational kingdom within Uganda. The kingdom of the Ganda people, Buganda is the largest of the traditional kingdoms in present-day Uganda, comprising all of Uganda's Central Region, including the Ugandan capital Kampala, with the exception of the disputed eastern Kayunga District...

, giving more power to Obote's party. Suspicions of fraud were compounded by Muwanga's announcement on the day of the election that all results should be cleared by him before they were announced publicly. The losing parties refused to recognise the legitimacy of the new regime, citing widespread electoral irregularities.

Obote II and the National Resistance Army

Museveni returned with his supporters to their rural strongholds in the Bantu-dominated south and southwest to form the Popular Resistance ArmyPopular Resistance Army

The Popular Resistance Army was a rebel group formed in 1980 by Yoweri Museveni to fight against the regime of Milton Obote....

(PRA). There they planned a rebellion against the second Obote regime, popularly known as "Obote II", and its armed forces, the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA). The insurgency began with an attack on an army installation in the central Mubende

Mubende

Mubende is a town in Central Uganda. It is the main municipal, administrative and commercial center of Mubende District and is the location of the district headquarters. Mubende is the sister city of Tumwater, Washington, USA.-Location:...

district on 6 February 1981. The PRA later merged with former president Yusufu Lule's fighting group, the Uganda Freedom Fighters

Uganda Freedom Fighters

The Uganda Freedom Fighters were a Ugandan rebel group led by former president Yusufu Lule. The group merged with Yoweri Museveni's Popular Resistance Army to create the National Resistance Army . The NRA would go on to topple the military junta of Tito Okello and take power in 1986....

(UFF), to create the National Resistance Army

National Resistance Army

The National Resistance Army , the military wing of the National Resistance Movement , was a rebel army that waged a guerrilla war, commonly referred to as the Luwero War or "the war in the bush", against the government of Milton Obote, and later that of Tito Okello.NRA was supported by Muammar...

(NRA) with its political wing, the National Resistance Movement

National Resistance Movement

The National Resistance Movement , commonly referred to as the Movement, is a political organization in Uganda.Until a referendum in 2005, Uganda held elections on a non-party basis. The NRM dominates parliament, however, and is expected to continue to do so. The presidential elections of 12 March...

(NRM). Two other rebel groups, the Uganda National Rescue Front

Uganda National Rescue Front

The Uganda National Rescue Front , refers to two former armed rebel groups in Uganda's West Nile sub-region that first opposed, then became incorporated into the Ugandan armed forces.-UNRF:...

(UNRF) and Former Uganda National Army (FUNA), formed in West Nile

West Nile sub-region

West Nile sub-region is a region in north-western Uganda that consists of the districts of Adjumani, Arua, Koboko, Maracha-Terego, Moyo, Nebbi and Yumbe...

from the remnants of Amin's supporters, engaged Obote's forces.

The NRM/A developed a "Ten-point Programme" for an eventual government, covering democracy, security, consolidation of national unity, defending national independence, building an independent, integrated and self-sustaining economy, improvement of social services, elimination of corruption and misuse of power, redressing inequality, cooperation with other African countries and a mixed economy.

By July 1985, Amnesty International

Amnesty International

Amnesty International is an international non-governmental organisation whose stated mission is "to conduct research and generate action to prevent and end grave abuses of human rights, and to demand justice for those whose rights have been violated."Following a publication of Peter Benenson's...

estimated that the Obote regime had been responsible for more than 300,000 civilian deaths across Uganda, although the CIA World Factbook puts the number at over 100,000. The human rights organisation had made several representations to the government to improve its appalling human rights record from 1982. Abuses were particularly conspicuous in an area of central Uganda known as the Luweero Triangle

Luwero triangle

The Luweero triangle, sometimes spelled Luwero Triangle, is an area of Uganda to the north of the capital Kampala, where Yoweri Museveni started the guerrilla war in 1981, that propelled him and his National Resistance Movement into power in 1986....

. Reports from Uganda during this period brought international criticism to the Obote regime and increased support abroad for Museveni's rebel force. Within Uganda, the brutal suppression of the insurgency aligned the Buganda, the most numerous of Uganda's ethnic groups, with the NRA against the UNLA, which was seen as being dominated by northerners, especially the Lango and Acholi. Until his death in 2005, Milton Obote

Milton Obote

Apolo Milton Obote , Prime Minister of Uganda from 1962 to 1966 and President of Uganda from 1966 to 1971, then again from 1980 to 1985. He was a Ugandan political leader who led Uganda towards independence from the British colonial administration in 1962.He was overthrown by Idi Amin in 1971, but...

blamed the Luwero abuses on the NRA.

1985 Nairobi Agreement

On 27 July 1985, subfactionalism within the UPC

Uganda People's Congress

The Uganda People's Congress is a political party in Uganda.Uganda People's Congress was founded in 1960 by Milton Obote, who led the country to Independence and later served two presidential terms under the party's banner...

government led to a successful military coup against Obote by his former army commander, Lieutenant-General Tito Okello

Tito Okello

General Tito Lutwa Okello , was a Ugandan Military officer and politician. He was the President of Uganda from 29 July 1985 until 26 January 1986.-Background:Tito Okello was born in 1914 in Kitgum District...

, an Acholi. Museveni and the NRM/A were angry that the revolution for which they had fought for four years had been "hijacked" by the UNLA, which they viewed as having been discredited by gross human rights violations during Obote II. Despite these reservations, however, the NRM/A eventually agreed to peace talks presided over by a Kenya

Kenya

Kenya , officially known as the Republic of Kenya, is a country in East Africa that lies on the equator, with the Indian Ocean to its south-east...

n delegation headed by President Daniel arap Moi

Daniel arap Moi

Daniel Toroitich arap Moi was the President of Kenya from 1978 until 2002.Daniel arap Moi is popularly known to Kenyans as 'Nyayo', a Swahili word for 'footsteps'...

.

The talks, which lasted from 26 August to 17 December, were notoriously acrimonious and the resultant ceasefire broke down almost immediately. The final agreement, signed in Nairobi

Nairobi

Nairobi is the capital and largest city of Kenya. The city and its surrounding area also forms the Nairobi County. The name "Nairobi" comes from the Maasai phrase Enkare Nyirobi, which translates to "the place of cool waters". However, it is popularly known as the "Green City in the Sun" and is...

, called for a ceasefire, demilitarisation of Kampala

Kampala

Kampala is the largest city and capital of Uganda. The city is divided into five boroughs that oversee local planning: Kampala Central Division, Kawempe Division, Makindye Division, Nakawa Division and Lubaga Division. The city is coterminous with Kampala District.-History: of Buganda, had chosen...

, integration of the NRA and government forces, and absorption of the NRA leadership into the Military Council. These conditions were never met.

The prospects of a lasting agreement were limited by several factors, including the Kenyan team's lack of an in-depth knowledge of the situation in Uganda and the exclusion of relevant Ugandan and international actors from the talks, inter alia. In the end, Museveni and his allies refused to share power with generals they did not respect, not least while the NRA had the capacity to achieve an outright military victory.

The push for Kampala

While supposedly involved in the peace negotiations, Museveni had courted General Mobutu Sese SekoMobutu Sese Seko

Mobutu Sese Seko Nkuku Ngbendu wa Za Banga , commonly known as Mobutu or Mobutu Sese Seko , born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, was the President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1965 to 1997...

of Zaire

Zaire

The Republic of Zaire was the name of the present Democratic Republic of the Congo between 27 October 1971 and 17 May 1997. The name of Zaire derives from the , itself an adaptation of the Kongo word nzere or nzadi, or "the river that swallows all rivers".-Self-proclaimed Father of the Nation:In...

in an attempt to forestall the involvement of Zairean forces in support of Okello's military junta. On 20 January 1986, however, several hundred troops loyal to Idi Amin were accompanied into Ugandan territory by the Zairean military. The forces intervened in the civil conflict following secret training in Zaire and an appeal from Okello ten days previously. Mobutu's support for Okello was a score Museveni would settle years later, ordering Ugandan forces into the conflict which would finally topple the Zairean leader

First Congo War

The First Congo War was a revolution in Zaire that replaced President Mobutu Sésé Seko, a decades-long dictator, with rebel leader Laurent-Désiré Kabila. Destabilization in eastern Zaire that resulted from the Rwandan genocide was the final factor that caused numerous internal and external actors...

.

Museveni was sworn in as president three days later on 26 January. "This is not a mere change of guard, it is a fundamental change," said Museveni after a ceremony conducted by British-born chief justice Peter Allen. Speaking to crowds of thousands outside the Ugandan parliament, the new president promised a return to democracy and said: "The people of Africa, the people of Uganda, are entitled to a democratic government. It is not a favour from any regime. The sovereign people must be the public, not the government."

Museveni in power (1986–96)

Political and economic regeneration

The post-AminIdi Amin

Idi Amin Dada was a military leader and President of Uganda from 1971 to 1979. Amin joined the British colonial regiment, the King's African Rifles in 1946. Eventually he held the rank of Major General in the post-colonial Ugandan Army and became its Commander before seizing power in the military...

regimes in Uganda were characterised by corruption

Political corruption

Political corruption is the use of legislated powers by government officials for illegitimate private gain. Misuse of government power for other purposes, such as repression of political opponents and general police brutality, is not considered political corruption. Neither are illegal acts by...

, factionalism

Sectarianism

Sectarianism, according to one definition, is bigotry, discrimination or hatred arising from attaching importance to perceived differences between subdivisions within a group, such as between different denominations of a religion, class, regional or factions of a political movement.The ideological...

and an inability to restore order and acquire popular legitimacy. Museveni needed to avoid repeating these mistakes if his new government was not to befall the same fate. The NRM declared a four-year interim government, composing a broader ethnic base than its predecessors. The representatives of the various factions were nevertheless hand-picked by Museveni. The sectarian violence which had overshadowed Uganda's recent history was put forward as a justification for restricting the activities of the political parties and their ethnically distinct supporter bases. The non-party

Non-partisan democracy

Nonpartisan democracy is a system of representative government or organization such that universal and periodic elections take place without reference to political parties.-Overview:...

system did not prohibit political parties, but prevented them from fielding candidates directly in elections. The so-called "Movement" system, which Museveni said claimed the loyalty of every Ugandan, would be a cornerstone in politics for nearly twenty years.

A system of Resistance Councils, directly elected at the parish level, was established to manage local affairs, including the equitable distribution of fixed-price commodities. The election of Resistance Councils representatives was the first direct experience many Ugandans had with democracy after many decades of varying levels of authoritarianism, and the replication of the structure up to the district level has been credited with helping even people at the local level understand the higher-level political structures.

The new government enjoyed widespread international support, and the economy that had been damaged by the civil war began to recover as Museveni initiated economic policies designed to combat key problems such as hyperinflation

Hyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is inflation that is very high or out of control. While the real values of the specific economic items generally stay the same in terms of relatively stable foreign currencies, in hyperinflationary conditions the general price level within a specific economy increases...

and the balance of payments

Balance of payments

Balance of payments accounts are an accounting record of all monetary transactions between a country and the rest of the world.These transactions include payments for the country's exports and imports of goods, services, financial capital, and financial transfers...

. Abandoning his Marxist

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

ideals, Museveni embraced the neoliberal structural adjustments advocated by the World Bank

World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans to developing countries for capital programmes.The World Bank's official goal is the reduction of poverty...

and the International Monetary Fund

International Monetary Fund