A Vindication of the Rights of Men

Encyclopedia

Pamphlet

A pamphlet is an unbound booklet . It may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths , or it may consist of a few pages that are folded in half and saddle stapled at the crease to make a simple book...

, written by the 18th-century British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft was an eighteenth-century British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. During her brief career, she wrote novels, treatises, a travel narrative, a history of the French Revolution, a conduct book, and a children's book...

, which attacks aristocracy

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

and advocates republicanism

Republicanism

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context...

. Wollstonecraft's was the first response in a pamphlet war

Revolution Controversy

The Revolution Controversy was a British debate over the French Revolution, lasting from 1789 through 1795. A pamphlet war began in earnest after the publication of Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France , which surprisingly supported the French aristocracy...

sparked by the publication of Edmund Burke's

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke PC was an Irish statesman, author, orator, political theorist and philosopher who, after moving to England, served for many years in the House of Commons of Great Britain as a member of the Whig party....

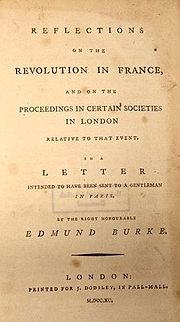

Reflections on the Revolution in France

Reflections on the Revolution in France

Reflections on the Revolution in France , by Edmund Burke, is one of the best-known intellectual attacks against the French Revolution...

(1790), a defence of constitutional monarchy, aristocracy, and the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

.

Wollstonecraft attacked not only hereditary privilege, but also the rhetoric that Burke used to defend it. Most of Burke's detractors deplored what they viewed as his theatrical pity for Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette ; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was an Archduchess of Austria and the Queen of France and of Navarre. She was the fifteenth and penultimate child of Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa and Holy Roman Emperor Francis I....

, but Wollstonecraft was unique in her love of Burke's gendered language. By saying the sublime

Sublime (philosophy)

In aesthetics, the sublime is the quality of greatness, whether physical, moral, intellectual, metaphysical, aesthetic, spiritual or artistic...

and the beautiful, terms first established by Burke himself in A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful

A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful

A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful is a 1757 treatise on aesthetics written by Edmund Burke. It attracted the attention of prominent Continental thinkers such as Denis Diderot and Immanuel Kant....

(1756), she kept his rhetoric as well as his argument. In her first abashedly feminist critique, which Wollstonecraft scholar Claudia Johnson

Claudia L. Johnson (scholar)

Claudia L. Johnson is the Murray Professor of English Literature at Princeton University; she is also currently chairperson of the English department. Johnson specializes in Restoration and 18th-century British literature, with an especial focus on the novel. She is also interested in feminist...

describes as unsurpassed in its argumentative force, Wollstonecraft indicts Burke's justification of an equal society founded on the passivity of women.

In her arguments for republican virtue, Wollstonecraft invokes an emerging middle-class ethos in opposition to what she views as the vice-ridden aristocratic code of manners. Driven by an Enlightenment

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

belief in progress, she derides Burke for relying on tradition and custom. She describes an idyllic country life in which each family has a farm sufficient for its needs. Wollstonecraft contrasts her utopia

Utopia

Utopia is an ideal community or society possessing a perfect socio-politico-legal system. The word was imported from Greek by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book Utopia, describing a fictional island in the Atlantic Ocean. The term has been used to describe both intentional communities that attempt...

n picture of society, drawn with what she claims is genuine feeling, with Burke's false theatrical tableaux.

The Rights of Men was successful: it was reviewed by every major periodical of the day and the first edition sold out in three weeks. However, upon the publication of the second edition (the first to carry Wollstonecraft's name on the title page), the reviews began to evaluate the text not only as a political pamphlet but also as the work of a female writer. They contrasted Wollstonecraft's "passion" with Burke's "reason" and spoke condescendingly of the text and its female author. This analysis of the Rights of Men prevailed until the 1970s, when feminist scholars

Feminist literary criticism

Feminist literary criticism is literary criticism informed by feminist theory, or by the politics of feminism more broadly. Its history has been broad and varied, from classic works of nineteenth-century women authors such as George Eliot and Margaret Fuller to cutting-edge theoretical work in...

began to read Wollstonecraft's texts with more care and called attention to their intellectualism.

Revolution Controversy

A Vindication of the Rights of Men was written against the backdrop of the French RevolutionFrench Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

and the debates that it provoked in Britain. In a lively and sometimes vicious pamphlet war, now referred to as the Revolution Controversy

Revolution Controversy

The Revolution Controversy was a British debate over the French Revolution, lasting from 1789 through 1795. A pamphlet war began in earnest after the publication of Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France , which surprisingly supported the French aristocracy...

, which lasted from 1789 until the end of 1795, British political commentators argued over the validity of monarchy. One scholar has called this debate "perhaps the last real discussion of the fundamentals of politics in [Britain]". The power of popular agitation in revolutionary France, demonstrated in events such as the Tennis Court Oath

Tennis Court Oath

The Tennis Court Oath was a pivotal event during the first days of the French Revolution. The Oath was a pledge signed by 576 of the 577 members from the Third Estate who were locked out of a meeting of the Estates-General on 20 June 1789...

and the storming of the Bastille

Storming of the Bastille

The storming of the Bastille occurred in Paris on the morning of 14 July 1789. The medieval fortress and prison in Paris known as the Bastille represented royal authority in the centre of Paris. While the prison only contained seven inmates at the time of its storming, its fall was the flashpoint...

in 1789, reinvigorated the British reform movement, which had been largely moribund for a decade. Efforts to reform the British electoral system and to distribute the seats in the House of Commons

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

more equitably were revived.

Much of the vigorous political debate in the 1790s was sparked by the publication of Edmund Burke's

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke PC was an Irish statesman, author, orator, political theorist and philosopher who, after moving to England, served for many years in the House of Commons of Great Britain as a member of the Whig party....

Reflections on the Revolution in France

Reflections on the Revolution in France

Reflections on the Revolution in France , by Edmund Burke, is one of the best-known intellectual attacks against the French Revolution...

in November 1790. Most commentators in Britain expected Burke to support the French revolutionaries, because he had previously been part of the liberal Whig

British Whig Party

The Whigs were a party in the Parliament of England, Parliament of Great Britain, and Parliament of the United Kingdom, who contested power with the rival Tories from the 1680s to the 1850s. The Whigs' origin lay in constitutional monarchism and opposition to absolute rule...

party, a critic of monarchical power, a supporter of the American revolution

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

aries, and a prosecutor of government malfeasance in India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

. When he failed to do so, it shocked the populace and angered his friends and supporters. Burke's book, despite being priced at an expensive three shilling

Shilling

The shilling is a unit of currency used in some current and former British Commonwealth countries. The word shilling comes from scilling, an accounting term that dates back to Anglo-Saxon times where it was deemed to be the value of a cow in Kent or a sheep elsewhere. The word is thought to derive...

s, sold an astonishing 30,000 copies in two years. Thomas Paine's

Thomas Paine

Thomas "Tom" Paine was an English author, pamphleteer, radical, inventor, intellectual, revolutionary, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States...

famous response, The Rights of Man (1792), which became the rallying cry for thousands, however, greatly surpassed it, selling upwards of 200,000 copies.

Wollstonecraft's Rights of Men was published only weeks after Burke's Reflections. While Burke supported aristocracy, monarchy, and the Established Church, liberals such as William Godwin

William Godwin

William Godwin was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism, and the first modern proponent of anarchism...

, Paine, and Wollstonecraft, argued for republicanism

Republicanism

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context...

, agrarian socialism, anarchy

Anarchy

Anarchy , has more than one colloquial definition. In the United States, the term "anarchy" typically is meant to refer to a society which lacks publicly recognized government or violently enforced political authority...

, and religious toleration. Most of those who came to be called radicals supported similar aims: individual liberties and civic virtue

Civic virtue

Civic virtue is the cultivation of habits of personal living that are claimed to be important for the success of the community. The identification of the character traits that constitute civic virtue have been a major concern of political philosophy...

. They were also united in the same broad criticisms: opposition to the bellicose "landed interest" and its role in government corruption, and opposition to a monarchy and aristocracy who they believed were unlawfully seizing the people's power.

1792 was the "annus mirabilis of eighteenth-century radicalism": its most important texts were published, and the influence of radical associations, such as the London Corresponding Society

London Corresponding Society

London Corresponding Society was a moderate-radical body concentrating on reform of the Parliament of Great Britain, founded on 25 January 1792. The creators of the group were John Frost , an attorney, and Thomas Hardy, a shoemaker and metropolitan Radical...

(LCS) and the Society for Constitutional Information

Society for Constitutional Information

Founded in 1780 by Major John Cartwright to promote parliamentary reform, the Society for Constitutional Information flourished until 1783, but thereafter made little headway...

(SCI), was at its height. However, it was not until these middle- and working-class groups formed an alliance with the genteel Society of the Friends of the People

Friends of the People Society

The Society of the Friends of the People was formed in Great Britain by Whigs at the end of the 18th century as part of a movement seeking radical political reform that would widen electoral enfranchisement at a time when only a wealthy minority had the vote...

that the government became concerned. After this alliance was formed, the conservative-dominated government prohibited seditious writings. Over 100 prosecutions for sedition took place in the 1790s alone, a dramatic increase from previous decades. The British government, fearing an uprising similar to the French Revolution, took even more drastic steps to quash the radicals: they made ever more political arrests and infiltrated radical groups; they threatened to "revoke the licences of publicans who continued to host politicised debating societies and to carry reformist literature"; they seized the mail of "suspected dissidents"; they supported groups that disrupted radical events; and they attacked dissidents in the press. Radicals saw this period, which included the 1794 Treason Trials

1794 Treason Trials

The 1794 Treason Trials, arranged by the administration of William Pitt, were intended to cripple the British radical movement of the 1790s. Over thirty radicals were initially arrested; three were tried for high treason: Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke and John Thelwall...

, as "the institution of a system of TERROR, almost as hideous in its features, almost as gigantic in its stature, and infinitely more pernicious in its tendency, than France ever knew."

When, in October 1795, crowds threw refuse at George III and insulted him, demanding a cessation of the war with France

French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars were a series of major conflicts, from 1792 until 1802, fought between the French Revolutionary government and several European states...

and lower bread prices, Parliament immediately passed the "gagging acts" (the Seditious Meetings Act

Seditious Meetings Act 1795

The Seditious Meetings Act 1795, approved by the British Parliament in November 1795, was the second of the well known "Two Acts" , the other being the Treason Act 1795. Its purpose was to restrict the size of public meetings to fifty persons...

and the Treasonable Practices Act

Treasonable Practices Act

The Treason Act 1795 was one of the Two Acts introduced by the British government in the wake of the stoning of King George III on his way to open Parliament in 1795, the other being the Seditious Meetings Act 1795...

, also known as the "Two Acts"). Under these new laws, it was almost impossible to hold public meetings and speech was severely curtailed at those that were held. British radicalism was effectively muted during the later 1790s and 1800s. It was not until the next generation that any real reform

Reform Act 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 was an Act of Parliament that introduced wide-ranging changes to the electoral system of England and Wales...

could be enacted.

Burke's Reflections

Published partially in response to DissentingEnglish Dissenters

English Dissenters were Christians who separated from the Church of England in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries.They originally agitated for a wide reaching Protestant Reformation of the Established Church, and triumphed briefly under Oliver Cromwell....

clergyman Richard Price's

Richard Price

Richard Price was a British moral philosopher and preacher in the tradition of English Dissenters, and a political pamphleteer, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the American Revolution. He fostered connections between a large number of people, including writers of the...

sermon celebrating the French revolution and partially in response to a young Frenchman's plea for guidance, Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France

Reflections on the Revolution in France

Reflections on the Revolution in France , by Edmund Burke, is one of the best-known intellectual attacks against the French Revolution...

defends aristocratic government, paternalism, loyalty, chivalry, and primogeniture

Primogeniture

Primogeniture is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn to inherit the entire estate, to the exclusion of younger siblings . Historically, the term implied male primogeniture, to the exclusion of females...

. He viewed the French Revolution as the violent overthrow of a legitimate government. In Reflections, he argues that citizens do not have the right to revolt against their government, because civilizations, including governments, are the result of social and political consensus. If a culture's traditions were continually challenged, he contends, the result would be anarchy.

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also called the Revolution of 1688, is the overthrow of King James II of England by a union of English Parliamentarians with the Dutch stadtholder William III of Orange-Nassau...

in 1688, which had restricted the powers of the monarchy, Burke argues that the appropriate historical analogy was the English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

(1642–1651), in which Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

had been executed in 1649. At the time Burke was writing, however, there had been very little revolutionary violence; more concerned with persuading his readers than informing them, he greatly exaggerated this element of the revolution in his text for rhetorical effect. In his Enquiry into the Sublime and Beautiful

A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful

A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful is a 1757 treatise on aesthetics written by Edmund Burke. It attracted the attention of prominent Continental thinkers such as Denis Diderot and Immanuel Kant....

, he had argued that "large inexact notions convey ideas best", and to generate fear in the reader, in Reflections he constructs the set-piece of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette ; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was an Archduchess of Austria and the Queen of France and of Navarre. She was the fifteenth and penultimate child of Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa and Holy Roman Emperor Francis I....

forced from their palace at sword point. When the violence actually escalated in France in 1793 with the Reign of Terror

Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror , also known simply as The Terror , was a period of violence that occurred after the onset of the French Revolution, incited by conflict between rival political factions, the Girondins and the Jacobins, and marked by mass executions of "enemies of...

, Burke was viewed as a prophet.

Burke also criticizes the learning associated with the French philosophes; he maintains that new ideas should not, in an imitation of the emerging discipline of science, be tested on society in an effort to improve it, but that populations should rely on custom and tradition to guide them.

Composition and publication of the Rights of Men

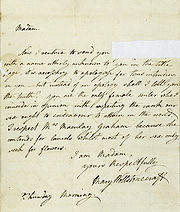

In the advertisement printed at the beginning of the Rights of Men, Wollstonecraft describes how and why she wrote it:So the pamphlet could be published as soon as she finished writing it, Wollstonecraft wrote frantically while her publisher Joseph Johnson

Joseph Johnson (publisher)

Joseph Johnson was an influential 18th-century London bookseller and publisher. His publications covered a wide variety of genres and a broad spectrum of opinions on important issues...

printed the pages. Halfway through the work, however, she ceased writing. One biographer describes it as a "loss of nerve"; Godwin, in his Memoirs

Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman is William Godwin's biography of his wife Mary Wollstonecraft, the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman ....

of Wollstonecraft, describes it as "a temporary fit of torpor and indolence". Johnson, perhaps canny enough at this point in their friendship to know how to encourage her, agreed to dispose of the book and told her not to worry about it. Ashamed, she rushed to finish.

Wollstonecraft's Rights of Men was published anonymously on 29 November 1790, the first of between fifty and seventy responses to Burke by various authors. Only three weeks later, on 18 December, a second edition, with her name printed on the title page, was issued. Wollstonecraft took time to edit the second edition, which, according to biographer Emily Sunstein, "sharpened her personal attack on Burke" and changed much of the text from first person

First-person narrative

First-person point of view is a narrative mode where a story is narrated by one character at a time, speaking for and about themselves. First-person narrative may be singular, plural or multiple as well as being an authoritative, reliable or deceptive "voice" and represents point of view in the...

to third person; "she also added a non-partisan code criticising hypocritical liberals who talk equality but scrape before the powers that be."

Structure and major arguments

Ad hominem

An ad hominem , short for argumentum ad hominem, is an attempt to negate the truth of a claim by pointing out a negative characteristic or belief of the person supporting it...

attacks (such as the suggestion that Burke would have promoted the crucifixion of Christ). It had been touted as an example of "feminine" emotion tilting at "masculine" reason. However, since the 1970s scholars have challenged this view, arguing that Wollstonecraft employed 18th-century modes of writing, such as the digression, to great rhetorical effect. More importantly, as scholar Mitzi Myers argues, "Wollstonecraft is virtually alone among those who answered Burke in eschewing a narrowly political approach for a wide-ranging critique of the foundation of the Reflections." Wollstonecraft makes a primarily moral argument; her "polemic is not a confutation of Burke's political theories, but an exposure of the cruel inequities which those theories presuppose." Wollstonecraft's style was also a deliberate choice, enabling her to respond to Burke's Enquiry into the Sublime and Beautiful as well as to Reflections.

The style of the Rights of Men mirrors much of Burke's own text. It has no clear structure; like Reflections, the text follows the mental associations made by the author as she was writing. Wollstonecraft's political treatise is written, like Burke's, in the form of a letter: his to C. J. F. DePont, a young Frenchman, and hers to Burke himself. Using the same form, metaphors, and style as Burke, she turns his own argument back on him. The Rights of Men is as much about language and argumentation as it is about political theory; in fact, Wollstonecraft claims that these are inseparable. She advocates, as one scholar writes, "simplicity and honesty of expression, and argument employing reason rather than eloquence." At the beginning of the pamphlet, she appeals to Burke: "Quitting now the flowers of rhetoric, let us, Sir, reason together."

The Rights of Men does not aim to present a fully articulated alternative political theory to Burke's, but instead to demonstrate the weaknesses and contradictions in his own argument. Therefore, much of the text is focused on Burke's logical inconsistencies, such as his support of the American revolution and the Regency Bill (which proposed restricting monarchical power during George III's madness in 1788), in contrast to his lack of support for the French revolutionaries. She writes:

Wollstonecraft's goal, she writes, is to "to shew you [Burke] to yourself, stripped of the gorgeous drapery in which you have enwrapped your tyrannic principles." However, she does also gesture towards a larger argument of her own, focusing on the inequalities faced by British citizens because of the class system. As Wollstonecraft scholar Barbara Taylor writes, "treating Burke as a representative spokesman for old-regime despotism, Wollstonecraft champions the reformist initiatives of the new French government against his 'rusty, baneful opinions', and censures British political elites for their opulence, corruption, and inhumane treatment of the poor."

Attack against rank and privilege

Wollstonecraft's attack on rank and hierarchy dominates the Rights of Men. She chastises Burke for his contempt for the people, whom he dismisses as the "swinish multitude", and berates him for supporting the elite, most notably Marie AntoinetteMarie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette ; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was an Archduchess of Austria and the Queen of France and of Navarre. She was the fifteenth and penultimate child of Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa and Holy Roman Emperor Francis I....

. In a famous passage, Burke had written: "I had thought ten thousand swords must have leaped from their scabbards to avenge even a look that threatened her with insult. – But the age of chivalry is gone." Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects , written by the 18th-century British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, is one of the earliest works of feminist philosophy. In it, Wollstonecraft responds to those educational and political theorists of the 18th...

(1792) and An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution (1794) extend the specific arguments made in the Rights of Men into larger social and political contexts.

Contrasting her middle-class values against Burke's aristocratic ones, Wollstonecraft contends that people should be judged on their merits rather than on their birthrights. As Wollstonecraft scholar Janet Todd

Janet Todd

Janet Margaret Todd is a Welsh-born academic and a well-respected author of many books on women in literature. Todd was educated at Cambridge University and the University of Florida, where she undertook a doctorate on the poet John Clare...

writes, "the vision of society revealed [in] A Vindication of the Rights of Men was one of talents, where entrepreneurial, unprivileged children could compete on equal terms with the now wrongly privileged." Wollstonecraft emphasizes the benefits of hard work, self-discipline, frugality, and morality, values she contrasts with the "vices of the rich", such as "insincerity" and the "want [i.e., lack] of natural affections". She endorses a commercial

Commercialism

Commercialism, in its original meaning, is the practices, methods, aims, and spirit of commerce or business. Today, however, it primarily refers to the tendency within open-market capitalism to turn everything into objects, images, and services sold for the purpose of generating profit...

society that would help individuals discover their own potential as well as force them to realize their civic responsibilities. For her, commercialism would be the great equalizing force. However, several years later, in Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark

Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark

Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark is a personal travel narrative by the eighteenth-century British feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft. The twenty-five letters cover a wide range of topics, from sociological reflections on Scandinavia and its peoples to...

(1796), she would question the ultimate benefits of commercialism to society.

While Dissenting

English Dissenters

English Dissenters were Christians who separated from the Church of England in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries.They originally agitated for a wide reaching Protestant Reformation of the Established Church, and triumphed briefly under Oliver Cromwell....

clergyman Richard Price

Richard Price

Richard Price was a British moral philosopher and preacher in the tradition of English Dissenters, and a political pamphleteer, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the American Revolution. He fostered connections between a large number of people, including writers of the...

, whose sermon helped spark Burke's work, is the villain of Reflections, he is the hero of the Rights of Men. Both Wollstonecraft and Burke associate him with Enlightenment

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

thinking, particularly the notion that civilization could progress through rational debate, but they interpret that stance differently. Burke believed such relentless questioning would lead to anarchy, while Wollstonecraft connected Price with "reason, liberty, free discussion, mental superiority, the improving exercise of the mind, moral excellence, active benevolence, orientation toward the present and future, and the rejection of power and riches"—quintessential middle-class professional values.

Wollstonecraft wields the English philosopher John Locke's

John Locke

John Locke FRS , widely known as the Father of Liberalism, was an English philosopher and physician regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers. Considered one of the first of the British empiricists, following the tradition of Francis Bacon, he is equally important to social...

definition of property (that is, ownership acquired through labour) against Burke's notion of inherited wealth. She contends that inheritance is one of the major impediments to the progress of European civilization, and repeatedly argues that Britain's problems are rooted in the inequity of property distribution. Although she did not advocate a totally equal distribution of wealth

Distribution of wealth

The distribution of wealth is a comparison of the wealth of various members or groups in a society. It differs from the distribution of income in that it looks at the distribution of ownership of the assets in a society, rather than the current income of members of that society.-Definition of...

, she did desire one that was more equitable.

Republicanism

Republicanism

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context...

ideology. Relying on 17th- and early 18th-century notions of republicanism, Wollstonecraft maintains that virtue is at the core of citizenship. However, her notion of virtue is more individualistic and moralistic than traditional Commonwealth

Commonwealth men

The Commonwealth men, Commonwealth's men, or Commonwealth Party were highly outspoken British Protestant religious, political, and economic reformers during the early 18th century. They were active in the movement called the Country Party...

ideology. The goals of Wollstonecraft's republicanism are the happiness and prosperity of the individual, not the greatest good for the greatest number or the greatest benefits for the propertied. While she emphasizes the benefits that will accrue to the individual under republicanism, she also maintains that reform can only be effected at a societal level. This marks a change from her earlier texts, such as Original Stories from Real Life

Original Stories from Real Life

Original Stories from Real Life; with Conversations Calculated to Regulate the Affections, and Form the Mind to Truth and Goodness is the only complete work of children's literature by 18th-century British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft. Original Stories begins with a frame story, which sketches out...

(1788), in which the individual plays the primary role in social reform.

Wollstonecraft's ideas of virtue revolved around the family, distinguishing her from other republicans such as Francis Hutcheson

Francis Hutcheson (philosopher)

Francis Hutcheson was a philosopher born in Ireland to a family of Scottish Presbyterians who became one of the founding fathers of the Scottish Enlightenment....

and William Godwin

William Godwin

William Godwin was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism, and the first modern proponent of anarchism...

. For Wollstonecraft, virtue begins in the home: private virtues are the foundation for public virtues. Inspired by Jean-Jacques Rousseau's

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer of 18th-century Romanticism. His political philosophy influenced the French Revolution as well as the overall development of modern political, sociological and educational thought.His novel Émile: or, On Education is a treatise...

depictions of the ideal family and the republican Swiss canton, she draws a picture of idyllic family life in a small country village. One scholar describes her plan this way: "vast estates would be divided into small farms, cottagers would be allowed to make enclosures from the commons and, instead of alms being given to the poor, they would be given the means to independence and self-advancement." Individuals would learn and practice virtue in the home, virtue that would not only make them self-sufficient, but also prompt them to feel responsible for the citizens of their society.

Tradition versus revolution

One of the central arguments of Wollstonecraft's Rights of Men is that rights should be conferred because they are reasonable and just, not because they are traditional. While Burke argued that civil society and government should rely on traditions which had accrued over centuries, Wollstonecraft contends that all civil agreements are subject to rational reassessment. Precedence, she maintains, is no reason to accept a law or a constitution. As one scholar puts it, "Burke's belief in the antiquity of the British constitution and the impossibility of improvement upon a system that has been tried and tested through time is dismissed as nonsense. The past, for Wollstonecraft, is a scene of superstition, oppression, and ignorance." Wollstonecraft believed powerfully in the EnlightenmentAge of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

notion of progress, and rejected the contention that ancient ideas could not be improved upon. Using Burke's own architectural language, she asks, "why was it a duty to repair an ancient castle, built in barbarous ages, of Gothic materials?" She also notes, pointedly, that Burke's philosophy condones slavery

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

:

Sensibility

Republicanism

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context...

, but also a social contract based on sympathy and fellow-feeling. She describes the ideal society in these terms: individuals, supported by cohesive families, connect with others through rational sympathy. Strongly influenced by Price, whom she had met at Newington Green

Newington Green

Newington Green is an open space in north London which straddles the border between Islington and Hackney. It gives its name to the surrounding area, roughly bounded by Ball's Pond Road to the south, Petherton Road to the west, the southern section of Stoke Newington with Green Lanes-Matthias Road...

just a few years earlier, Wollstonecraft asserts that people should strive to imitate God by practicing universal benevolence.

Embracing a reasoned sensibility

Sensibility

Sensibility refers to an acute perception of or responsiveness toward something, such as the emotions of another. This concept emerged in eighteenth-century Britain, and was closely associated with studies of sense perception as the means through which knowledge is gathered...

, Wollstonecraft contrasts her theory of civil society with Burke's, which she describes as full of pomp and circumstance and riddled with prejudice. She attacks what she perceives as Burke's false feeling, countering with her own genuine emotion. She argues that to be sympathetic to the French revolution (i.e., the people) is humane while to sympathize with the French clergy, as Burke does, is a mark of inhumanity. She accuses Burke not only of insincerity, but also of manipulation, claiming that his Reflections is propaganda. In one of the most dramatic moments of the Rights of Men, Wollstonecraft claims to be moved beyond Burke's tears for Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette ; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was an Archduchess of Austria and the Queen of France and of Navarre. She was the fifteenth and penultimate child of Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa and Holy Roman Emperor Francis I....

and the monarchy of France to silence for the injustice suffered by slaves, a silence she represents with dashes meant to express feelings more authentic than Burke's:

Gender and aesthetics

Sublime (philosophy)

In aesthetics, the sublime is the quality of greatness, whether physical, moral, intellectual, metaphysical, aesthetic, spiritual or artistic...

and the beautiful, terms he had established in his Enquiry into the Sublime and Beautiful

A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful

A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful is a 1757 treatise on aesthetics written by Edmund Burke. It attracted the attention of prominent Continental thinkers such as Denis Diderot and Immanuel Kant....

. While Burke associates the beautiful with weakness and femininity, and the sublime with strength and masculinity, Wollstonecraft writes, "for truth, in morals, has ever appeared to me the essence of the sublime; and, in taste, simplicity the only criterion of the beautiful." With this sentence, she calls into question Burke's gendered definitions; convinced that they are harmful, she argues later in the Rights of Men:

As Wollstonecraft scholar Claudia Johnson

Claudia L. Johnson (scholar)

Claudia L. Johnson is the Murray Professor of English Literature at Princeton University; she is also currently chairperson of the English department. Johnson specializes in Restoration and 18th-century British literature, with an especial focus on the novel. She is also interested in feminist...

has written, "As feminist critique, these passages have never really been surpassed." Burke, Wollstonecraft maintains, describes womanly virtue as weakness, thus leaving women no substantive roles in the public sphere and relegating them to uselessness.

Wollstonecraft applies this feminist critique to Burke's language throughout the Reflections. As Johnson argues, "her pamphlet as a whole refutes the Burkean axiom 'to make us love our country, our country ought to be lovely'"; Wollstonecraft successfully challenges Burke's rhetoric of the beautiful with the rhetoric of the rational. She also demonstrates how Burke embodies the worst of his own ideas. He becomes the hysterical, illogical, feminine writer, and Wollstonecraft becomes the rational, masculine writer. Ironically, in order to effect this transposition, Wollstonecraft herself becomes passionate at times, for example, in her description of slavery (quoted above).

Reception and legacy

Commentaries from the time note this; Horace Walpole

Horace Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford

Horatio Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford was an English art historian, man of letters, antiquarian and Whig politician. He is now largely remembered for Strawberry Hill, the home he built in Twickenham, south-west London where he revived the Gothic style some decades before his Victorian successors,...

, for example, called her a "hyena in petticoats" for attacking Marie Antoinette. William Godwin

William Godwin

William Godwin was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism, and the first modern proponent of anarchism...

, her future husband, described the book as illogical and ungrammatical; in his Memoirs

Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman is William Godwin's biography of his wife Mary Wollstonecraft, the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman ....

of Wollstonecraft, he dedicated only a paragraph to a discussion of the content of the work, calling it "intemperate".

All the major periodicals of the day reviewed the Rights of Men. The Analytical Review

Analytical Review

The Analytical Review was a periodical established in London in 1788 by the publisher Joseph Johnson and the writer Thomas Christie. Part of the Republic of Letters, it was a gadfly publication, which offered readers summaries and analyses of the many new publications issued at the end of the...

agreed with Wollstonecraft's arguments and praised her "lively and animated remarks". The Monthly Review was also sympathetic, but it pointed out faults in her writing. The Critical Review, the "sworn foe" of the Analytical Review, however, wrote in December 1790, after discovering that the author was a woman:

The Gentleman's Magazine followed suit, criticizing the book's logic and "its absurd presumption that men will be happier if free", as well as Wollstonecraft's own presumption in writing on topics outside of her proper domain, commenting "the rights of men asserted by a fair lady! The age of chivalry cannot be over, or the sexes have changed their ground." However, the Rights of Men put Wollstonecraft on the map as a writer; from this point forward in her career, she was well-known.

Wollstonecraft sent a copy of the book to the historian Catharine Macaulay, whom she greatly admired. Macaulay wrote back that she was "still more highly pleased that this publication which I have so greatly admired from its pathos & sentiment should have been written by a woman and thus to see my opinion of the powers and talents of the sex in your pen so early verified." William Roscoe

William Roscoe

William Roscoe , was an English historian and miscellaneous writer.-Life:He was born in Liverpool, where his father, a market gardener, kept a public house called the Bowling Green at Mount Pleasant. Roscoe left school at the age of twelve, having learned all that his schoolmaster could teach...

, a Liverpool lawyer, writer, and patron of the arts, liked the book so much that he included Wollstonecraft in his satirical poem The Life, Death, and Wonderful Achievements of Edmund Burke:

And lo! an amazon stept out,

- One WOLLSTONECRAFT her name,

Resolv'd to stop his mad career,

- Whatever chance became.

While most of the early reviewers of the Rights of Men, as well as most of Wollstonecraft's early biographers, criticized the work's emotionalism, and juxtaposed it with Burke's masterpiece of logic, there has been a recent re-evaluation of her text. Since the 1970s, critics who have looked more closely at both her work and Burke's, have come to the conclusion that they share many rhetorical similarities, and that the masculine/logic and feminine/emotion binaries are unsupportable. Most Wollstonecraft scholars now recognize it was this work that radicalized Wollstonecraft and directed her future writings, particularly A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects , written by the 18th-century British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, is one of the earliest works of feminist philosophy. In it, Wollstonecraft responds to those educational and political theorists of the 18th...

. It is not until after the halfway point of Rights of Men that she begins the dissection of Burke's gendered aesthetic; as Claudia Johnson contends, "it seems that in the act of writing the later portions of Rights of Men she discovered the subject that would preoccupy her for the rest of her career."

Two years later, when Wollstonecraft published the Rights of Woman, she extended many of the arguments she had begun in Rights of Men. If all people should be judged on their merits, she wrote, women should be included in that group. In both texts, Wollstonecraft emphasizes that the virtue of the British nation is dependent on the virtue of its people. To a great extent, she collapses the distinction between private and public and demands that all educated citizens be offered the chance to participate in the public sphere.

Primary sources

- Burke, EdmundEdmund BurkeEdmund Burke PC was an Irish statesman, author, orator, political theorist and philosopher who, after moving to England, served for many years in the House of Commons of Great Britain as a member of the Whig party....

. Reflections on the Revolution in FranceReflections on the Revolution in FranceReflections on the Revolution in France , by Edmund Burke, is one of the best-known intellectual attacks against the French Revolution...

. Ed. Conor Cruise O'Brien. New York: Penguin Books, 1986. ISBN 0-14-043204-3. - Butler, MarilynMarilyn ButlerMarilyn Butler is a British literary critic. She was Rector of Exeter College, Oxford from 1993 to 2004, and was King Edward VII Professor of English Literature at the University of Cambridge, from 1986 to 1993...

, ed. Burke, Paine, Godwin, and the Revolution Controversy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-521-28656-5. - Godwin, WilliamWilliam GodwinWilliam Godwin was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism, and the first modern proponent of anarchism...

. Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of WomanMemoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of WomanMemoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman is William Godwin's biography of his wife Mary Wollstonecraft, the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman ....

. Eds. Pamela Clemit and Gina Luria Walker. Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2001. ISBN 1-55111-259-0. - Wollstonecraft, MaryMary WollstonecraftMary Wollstonecraft was an eighteenth-century British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. During her brief career, she wrote novels, treatises, a travel narrative, a history of the French Revolution, a conduct book, and a children's book...

. The Complete Works of Mary Wollstonecraft. Ed. Janet Todd and Marilyn Butler. 7 vols. London: William Pickering, 1989. ISBN 0-8147-9225-1. - Wollstonecraft, Mary. The Vindications: The Rights of Men and The Rights of Woman. Eds. D.L. Macdonald and Kathleen Scherf. Toronto: Broadview Literary Texts, 1997. ISBN 1-55111-088-1.

Contemporary reviews

- Analytical ReviewAnalytical ReviewThe Analytical Review was a periodical established in London in 1788 by the publisher Joseph Johnson and the writer Thomas Christie. Part of the Republic of Letters, it was a gadfly publication, which offered readers summaries and analyses of the many new publications issued at the end of the...

8 (1790): 416–419. - Critical ReviewThe Critical ReviewThe Critical Review was first edited by Tobias Smollett from 1756 to 1763, and was contributed to by Samuel Johnson, David Hume, John Hunter, and Oliver Goldsmith, until 1817....

70 (1790): 694–696. - English Review 17 (1791): 56–61.

- General Magazine and Impartial Review 4 (1791): 26–27.

- Gentleman's Magazine 61.1 (1791): 151–154.

- Monthly Review New Series 4 (1791): 95–97.

- New Annual Register 11 (1790): 237.

- Universal Magazine and Review 5 (1791): 77–78.

- Walker's Hibernian Magazine 1 (1791): 269–271 [copied from the Gentleman's Magazine]

Secondary sources

- Barrell, John and Jon Mee, eds. "Introduction". Trials for Treason and Sedition, 1792–1794. 8 vols. London: Pickering and Chatto, 2006-7. ISBN 978-1-85196-732-2.

- Furniss, Tom. "Mary Wollstonecraft's French Revolution". The Cambridge Companion to Mary Wollstonecraft. Ed. Claudia L. Johnson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-521-78952-4.

- Johnson, Claudia L.Claudia L. Johnson (scholar)Claudia L. Johnson is the Murray Professor of English Literature at Princeton University; she is also currently chairperson of the English department. Johnson specializes in Restoration and 18th-century British literature, with an especial focus on the novel. She is also interested in feminist...

Equivocal Beings: Politics, Gender, and Sentimentality in the 1790s. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995. ISBN 0-226-40184-7. - Jones, Chris. "Mary Wollstonecraft's Vindications and their political tradition". The Cambridge Companion to Mary Wollstonecraft. Ed. Claudia L. Johnson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-521-78952-4.

- Keen, Paul. The Crisis of Literature in the 1790s: Print Culture and the Public Sphere. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-521-65325-8.

- Kelly, Gary. Revolutionary Feminism: The Mind and Career of Mary Wollstonecraft. New York: St. Martin's, 1992. ISBN 0-312-12904-1.

- Myers, Mitzi. "Politics from the Outside: Mary Wollstonecraft's First Vindication". Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture 6 (1977): 113–32.

- Paulson, Ronald. Representations of Revolution, 1789–1820. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983. ISBN 0-300-02864-4.

- Poovey, Mary. The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984. ISBN 0-226-67528-9.

- Sapiro, Virginia. A Vindication of Political Virtue: The Political Theory of Mary Wollstonecraft. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992. ISBN 0-226-73491-9.

- Sunstein, Emily. A Different Face: the Life of Mary Wollstonecraft. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1975. ISBN 0-06-014201-4.

- Taylor, Barbara. Mary Wollstonecraft and the Feminist Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-521-66144-7.

- Todd, JanetJanet ToddJanet Margaret Todd is a Welsh-born academic and a well-respected author of many books on women in literature. Todd was educated at Cambridge University and the University of Florida, where she undertook a doctorate on the poet John Clare...

. Mary Wollstonecraft: A Revolutionary Life. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 2000. ISBN 0-231-12184-9. - Wardle, Ralph M. Mary Wollstonecraft: A Critical Biography. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1951.

External links

- Full text of Rights of Men at the Online Library of Liberty

- Mary Wollstonecraft: A 'Speculative and Dissenting Spirit' by Janet Todd at www.bbc.co.uk