Joseph Johnson (publisher)

Encyclopedia

Joseph Johnson was an influential 18th-century London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

bookseller and publisher. His publications covered a wide variety of genres and a broad spectrum of opinions on important issues. Johnson is best known for publishing the works of radical thinkers such as Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft was an eighteenth-century British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. During her brief career, she wrote novels, treatises, a travel narrative, a history of the French Revolution, a conduct book, and a children's book...

, William Godwin

William Godwin

William Godwin was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism, and the first modern proponent of anarchism...

, and Joel Barlow

Joel Barlow

Joel Barlow was an American poet, diplomat and politician. In his own time, Barlow was well-known for the epic Vision of Columbus. Modern readers may be more familiar with "The Hasty Pudding"...

, as well as religious dissenters

English Dissenters

English Dissenters were Christians who separated from the Church of England in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries.They originally agitated for a wide reaching Protestant Reformation of the Established Church, and triumphed briefly under Oliver Cromwell....

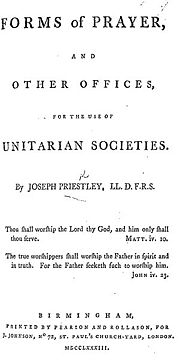

such as Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley, FRS was an 18th-century English theologian, Dissenting clergyman, natural philosopher, chemist, educator, and political theorist who published over 150 works...

, Anna Laetitia Barbauld

Anna Laetitia Barbauld

Anna Laetitia Barbauld was a prominent English poet, essayist, literary critic, editor, and children's author.A "woman of letters" who published in multiple genres, Barbauld had a successful writing career at a time when female professional writers were rare...

, and Gilbert Wakefield

Gilbert Wakefield

Gilbert Wakefield was an English scholar and controversialist.Gilbert Wakefield was the third son of the Rev. George Wakefield, then rector of St Nicholas' Church, Nottingham but afterwards at Kingston-upon-Thames. He was educated at Jesus College, Cambridge, where he graduated B.A. as second...

.

In the 1760s, Johnson established his publishing business, which focused primarily on religious works. He also became friends with Priestley and the artist Henry Fuseli

Henry Fuseli

Henry Fuseli was a British painter, draughtsman, and writer on art, of Swiss origin.-Biography:...

—two relationships that lasted his entire life and brought him much business. In the 1770s and 1780s, Johnson expanded his business, publishing important works in medicine and children's literature as well as the popular poetry of William Cowper

William Cowper

William Cowper was an English poet and hymnodist. One of the most popular poets of his time, Cowper changed the direction of 18th century nature poetry by writing of everyday life and scenes of the English countryside. In many ways, he was one of the forerunners of Romantic poetry...

and Erasmus Darwin

Erasmus Darwin

Erasmus Darwin was an English physician who turned down George III's invitation to be a physician to the King. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave trade abolitionist,inventor and poet...

. Throughout his career, Johnson helped shape the thought of his era not only through his publications, but also through his support of innovative writers and thinkers. He fostered the open discussion of new ideas, particularly at his famous weekly dinners, the regular attendees of which became known as the "Johnson Circle".

In the 1790s, Johnson aligned himself with the supporters of the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

, and published an increasing number of political pamphlets in addition to a prominent journal, the Analytical Review

Analytical Review

The Analytical Review was a periodical established in London in 1788 by the publisher Joseph Johnson and the writer Thomas Christie. Part of the Republic of Letters, it was a gadfly publication, which offered readers summaries and analyses of the many new publications issued at the end of the...

, which offered British reformers a voice in the public sphere. In 1799, he was indicted on charges of seditious libel

Seditious libel

Seditious libel was a criminal offence under English common law. Sedition is the offence of speaking seditious words with seditious intent: if the statement is in writing or some other permanent form it is seditious libel...

for publishing a pamphlet by the Unitarian

Unitarianism

Unitarianism is a Christian theological movement, named for its understanding of God as one person, in direct contrast to Trinitarianism which defines God as three persons coexisting consubstantially as one in being....

minister Gilbert Wakefield

Gilbert Wakefield

Gilbert Wakefield was an English scholar and controversialist.Gilbert Wakefield was the third son of the Rev. George Wakefield, then rector of St Nicholas' Church, Nottingham but afterwards at Kingston-upon-Thames. He was educated at Jesus College, Cambridge, where he graduated B.A. as second...

. After spending six months in prison, albeit under relatively comfortable conditions, Johnson published fewer political works. In the last decade of his career, Johnson did not seek out many new writers; however, he remained successful by publishing the collected works of authors such as William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon"...

.

Johnson's friend John Aikin

John Aikin

John Aikin was an English doctor and writer.-Life:He was born at Kibworth Harcourt, Leicestershire, England, son of Dr. John Aikin, Unitarian divine, and received his elementary education at the Nonconformist academy at Warrington, where his father was a tutor. He studied medicine at the...

eulogized him as "the father of the booktrade". He has also been called "the most important publisher in England from 1770 until 1810" for his appreciation and promotion of young writers, his emphasis on publishing inexpensive works directed at a growing middle-class readership, and his cultivation and advocacy of women writers at a time when they were viewed with scepticism.

Early life

Johnson was the second son of Rebecca Turner Johnson and John Johnson, a BaptistBaptist

Baptists comprise a group of Christian denominations and churches that subscribe to a doctrine that baptism should be performed only for professing believers , and that it must be done by immersion...

yeoman who lived in Everton, Liverpool. Religious Dissent

English Dissenters

English Dissenters were Christians who separated from the Church of England in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries.They originally agitated for a wide reaching Protestant Reformation of the Established Church, and triumphed briefly under Oliver Cromwell....

marked Johnson from the beginning of his life, as two of his mother's relatives were prominent Baptist ministers and his father was a deacon

Deacon

Deacon is a ministry in the Christian Church that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions...

. Liverpool

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880...

, at the time of Johnson's youth

History of Liverpool

The history of Liverpool can be traced back to 1190 when the place was known as 'Liuerpul', possibly meaning a pool or creek with muddy water. Other origins of the name have been suggested, including 'elverpool', a reference to the large number of eels in the Mersey, but the definitive origin is...

, was fast becoming a bustling urban centre and was one of the most important commercial ports in England. These two characteristics of his home—Dissent and commercialism—remained central elements in Johnson's character throughout his life.

At the age of fifteen, Johnson was apprenticed to George Keith, a London bookseller who specialized in publishing religious tracts

Tract (literature)

A tract is a literary work, and in current usage, usually religious in nature. The notion of what constitutes a tract has changed over time. By the early part of the 21st century, these meant small pamphlets used for religious and political purposes, though far more often the former. They are...

such as Reflections on the Modern but Unchristian Practice of Innoculation

Vaccine controversy

A vaccine controversy is a dispute over the morality, ethics, effectiveness, or safety of vaccinations. Medical and scientific evidence surrounding vaccinations generally demonstrate that the benefits of preventing suffering and death from infectious diseases outweigh rare adverse effects of...

. As Gerald Tyson, Johnson's major modern biographer, explains, it was unusual for the younger son of a family living in relative obscurity to move to London and to become a bookseller. Scholars have speculated that Johnson was indentured to Keith because the bookseller was associated with Liverpool Baptists. Keith and Johnson published several works together later in their careers, which suggests that the two remained on friendly terms after Johnson started his own business.

1760s: Beginnings in publishing

Upon completing his apprenticeship in 1761, Johnson opened his own business, but he struggled to establish himself, moving his shop several times within one year. Two of his early publications were a kind of day planner: The Complete Pocket-Book; Or, Gentleman and Tradesman's Daily Journal for the Year of Our Lord, 1763 and The Ladies New and Polite Pocket Memorandum Book. Such pocketbooks were popular and Johnson outsold his rivals by publishing his both earlier and cheaper. Johnson continued to sell these profitable books until the end of the 1790s, but as a religious Dissenter, he was primarily interested in publishing books that would improve society. Therefore, religious texts dominated his book list, although he also published works relating to Liverpool (his home town) and medicine. However, as a publisher Johnson attended to more than the selling and distributing of books, as scholar Leslie Chard explains:As Johnson became successful and his reputation grew, other publishers began including him in congers

Conger (syndicate)

The conger was a system common in bookselling in 18th and early 19th century England, for financing the printing of a book. The term referred to a syndicate of booksellers, mostly in London, who bought shares to finance the book's printing. Each member agreed to take so many copies for sale...

—syndicates that spread the risk of publishing a costly or inflammatory book among several firms.

Formative friendships

In his late twenties, Johnson formed two friendships that were to shape the rest of his life. The first was with the painter and writer Henry FuseliHenry Fuseli

Henry Fuseli was a British painter, draughtsman, and writer on art, of Swiss origin.-Biography:...

, who was described as "quick witted and pugnacious". Fuseli's early 19th-century biographer writes that when Fuseli met Johnson in 1764, Johnson "had already acquired the character which he retained during life,—that of a man of great integrity, and encourager of literary men as far as his means extended, and an excellent judge of their productions". Fuseli became and remained Johnson's closest friend.

Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley, FRS was an 18th-century English theologian, Dissenting clergyman, natural philosopher, chemist, educator, and political theorist who published over 150 works...

, the renowned natural philosopher and Unitarian

Unitarianism

Unitarianism is a Christian theological movement, named for its understanding of God as one person, in direct contrast to Trinitarianism which defines God as three persons coexisting consubstantially as one in being....

theologian. This friendship led Johnson to discard the Baptist faith of his youth and to adopt Unitarianism, as well as to pursue forms of political dissent. Johnson's success as a publisher can be explained in large part through his association with Priestley, as Priestley published dozens of books with him and introduced him to many other Dissenting writers. Through Priestley's recommendation, Johnson was able to issue the works of many Dissenters, especially those from Warrington Academy

Warrington Academy

Warrington Academy, active as a teaching establishment from 1756 to 1782, was a prominent dissenting academy, that is, a school or college set up by those who dissented from the state church in England...

: the poet, essayist, and children's author Anna Laetitia Barbauld

Anna Laetitia Barbauld

Anna Laetitia Barbauld was a prominent English poet, essayist, literary critic, editor, and children's author.A "woman of letters" who published in multiple genres, Barbauld had a successful writing career at a time when female professional writers were rare...

; her brother, the physician and writer, John Aikin

John Aikin

John Aikin was an English doctor and writer.-Life:He was born at Kibworth Harcourt, Leicestershire, England, son of Dr. John Aikin, Unitarian divine, and received his elementary education at the Nonconformist academy at Warrington, where his father was a tutor. He studied medicine at the...

; the naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster

Johann Reinhold Forster

Johann Reinhold Forster was a German Lutheran pastor and naturalist of partial Scottish descent who made contributions to the early ornithology of Europe and North America...

; the Unitarian minister and controversialist Gilbert Wakefield

Gilbert Wakefield

Gilbert Wakefield was an English scholar and controversialist.Gilbert Wakefield was the third son of the Rev. George Wakefield, then rector of St Nicholas' Church, Nottingham but afterwards at Kingston-upon-Thames. He was educated at Jesus College, Cambridge, where he graduated B.A. as second...

; the moralist William Enfield

William Enfield

William Enfield was a British Unitarian minister who published a bestselling book on elocution entitled The Speaker .-Life:...

; and the political economist Thomas Malthus

Thomas Malthus

The Reverend Thomas Robert Malthus FRS was an English scholar, influential in political economy and demography. Malthus popularized the economic theory of rent....

. Tyson writes that "the relationship between the Academy and the bookseller was mutually very useful. Not only did many of the tutors send occasional manuscripts for publication, but also former pupils often sought him out in later years to issue their works." By printing the works of Priestley and other of the Warrington tutors, Johnson also made himself known to an even larger network of Dissenting intellectuals, including those in the Lunar Society

Lunar Society

The Lunar Society of Birmingham was a dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the Midlands Enlightenment, including industrialists, natural philosophers and intellectuals, who met regularly between 1765 and 1813 in Birmingham, England. At first called the Lunar Circle,...

, which expanded his business further. Priestley, in turn, trusted Johnson enough to handle the logistics of his induction into the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

.

Partnerships

In July 1765, Johnson moved his business to the more visible 8 Paternoster RowPaternoster Row

Paternoster Row was a London street in which clergy of the medieval St Paul's Cathedral would walk, chanting the Lord's Prayer . It was devastated by aerial bombardment in The Blitz during World War II. Prior to this destruction the area had been a centre of the London publishing trade , with...

and formed a partnership with B. Davenport, of whom little is known aside from his association with Johnson. Chard postulates that they were attracted by mutual beliefs because the firm of Johnson and Davenport published even more religious works, including many that were "rigidly Calvinistic". However, in the summer of 1767, Davenport and Johnson parted ways; scholars have speculated that this rupture occurred because Johnson's religious views were becoming more unorthodox.

Newly independent, with a solid reputation, Johnson did not need to struggle to establish himself as he had early in his career. Within a year, he published nine first editions himself as well as thirty-two works in partnership with other booksellers. He was also a part of "the select circle of bookmen that gathered at the Chapter Coffee House

Coffeehouse

A coffeehouse or coffee shop is an establishment which primarily serves prepared coffee or other hot beverages. It shares some of the characteristics of a bar, and some of the characteristics of a restaurant, but it is different from a cafeteria. As the name suggests, coffeehouses focus on...

", which was the centre of social and commercial life for publishers and booksellers in 18th-century London. Major publishing ventures had started at the Chapter and important writers "clubbed" there.

In 1768 Johnson went into partnership with John Payne (Johnson was probably the senior partner); the following year they published 50 titles. Under Johnson and Payne, the firm published a wider array of works than under Johnson and Davenport. Although Johnson looked to his business interests, he did not publish works only to enrich himself. Projects that encouraged free discussion appealed to Johnson; for example, he helped Priestley publish the Theological Repository

Theological Repository

The Theological Repository was a periodical founded and edited from 1769 to 1771 by the eighteenth-century British polymath Joseph Priestley...

, a financial failure that nevertheless fostered open debate of theological questions. Although the journal lost Johnson money in the 1770s, he was willing to begin publishing it again in 1785 because he endorsed its values.

The late 1760s was a time of growing radicalism in Britain, and although Johnson did not participate actively in the events, he facilitated the speech of those who did, e.g., by publishing works on the disputed election of John Wilkes

John Wilkes

John Wilkes was an English radical, journalist and politician.He was first elected Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlesex election dispute, he fought for the right of voters—rather than the House of Commons—to determine their representatives...

and the agitation in the American colonies

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

. Despite his growing interest in politics, Johnson (with Payne) still published primarily religious works and the occasional travel narrative

Travel literature

Travel literature is travel writing of literary value. Travel literature typically records the experiences of an author touring a place for the pleasure of travel. An individual work is sometimes called a travelogue or itinerary. Travel literature may be cross-cultural or transnational in focus, or...

. As Tyson writes, "in the first decade of his career Johnson's significance as a bookseller derived from a desire to provide dissent (religious and political) a forum".

Fire

Johnson was on the verge of real success when his shop was ravaged by fire on 9 January 1770. As one London newspaper reported it:At the time Fuseli had been living with Johnson and he also lost all of his possessions, including the first printing of his Remarks on the Writings and Conduct of J. J. Rousseau. Johnson and Payne subsequently dissolved their partnership. It was an amicable separation, and Johnson even published some of Payne's works in later years.

1770s: Establishment

By August 1770, just seven months after fire had destroyed his shop and goods, Johnson had re-established himself at 72 St. Paul's Churchyard—the largest shop on a street of booksellers—where he was to remain for the rest of his life. How Johnson managed this feat is unclear; he later cryptically told a friend that "his friends came about him, and set him up again". An early 19th-century biography states that "Mr. Johnson was now so well known, and had been so highly respected, that on this unfortunate occasion, his friends with one accord met, and contributed to enable him to begin business again". Chard speculates that Priestley assisted him since they were such close friends.Religious publications and advocacy of Unitarianism

English Dissenters

English Dissenters were Christians who separated from the Church of England in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries.They originally agitated for a wide reaching Protestant Reformation of the Established Church, and triumphed briefly under Oliver Cromwell....

. Starting in the 1770s, Johnson published more specifically Unitarian

Unitarianism

Unitarianism is a Christian theological movement, named for its understanding of God as one person, in direct contrast to Trinitarianism which defines God as three persons coexisting consubstantially as one in being....

works, as well as texts advocating religious toleration

Religious toleration

Toleration is "the practice of deliberately allowing or permitting a thing of which one disapproves. One can meaningfully speak of tolerating, ie of allowing or permitting, only if one is in a position to disallow”. It has also been defined as "to bear or endure" or "to nourish, sustain or preserve"...

; he also became personally involved in the Unitarian cause. He served as a conduit for information between Dissenters across the country and supplied provincial publishers with religious publications, thereby enabling Dissenters to spread their beliefs easily. Johnson participated in efforts to repeal the Test

Test Act

The Test Acts were a series of English penal laws that served as a religious test for public office and imposed various civil disabilities on Roman Catholics and Nonconformists...

and Corporation Acts

Corporation Act 1661

The Corporation Act of 1661 is an Act of the Parliament of England . It belongs to the general category of test acts, designed for the express purpose of restricting public offices in England to members of the Church of England....

, which restricted the civil rights of Dissenters. In one six-year period of the 1770s, Johnson was responsible for publishing nearly one-third of the Unitarian works on the issue. He continued his support in 1787, 1789, and 1790, when Dissenters introduced repeal bills in Parliament

Parliament of Great Britain

The Parliament of Great Britain was formed in 1707 following the ratification of the Acts of Union by both the Parliament of England and Parliament of Scotland...

, and he published much of the pro-repeal literature written by Priestley and others.

Johnson was also instrumental in Theophilus Lindsey's

Theophilus Lindsey

Theophilus Lindsey was an English theologian and clergyman who founded the first avowedly Unitarian congregation in the country, at Essex Street Chapel.-Life:...

founding of the first Unitarian chapel in London. With some difficulty, as Unitarians were feared at that time and their beliefs held illegal until the Doctrine of the Trinity Act 1813

Doctrine of the Trinity Act 1813

The Doctrine of the Trinity Act 1813 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom...

, Johnson obtained the building for Essex Street Chapel

Essex Street Chapel

Essex Street Chapel, also known as Essex Church, is a Unitarian place of worship in London. It was the first church in England set up with this doctrine, and was established at a time when Dissenters still faced legal threat...

and, with the help of barrister John Lee

John Lee (Attorney-General)

John Lee KC was an English lawyer, politician, and law officer of the Crown. He assisted in the early days of Unitarianism in England.-Life:...

, who later became Attorney-General, its licence. To capitalize on the opening of the new chapel in addition to helping out his friends, Johnson published Lindsey's inaugural sermon, which sold out in four days. Johnson continued to attend and participate actively in this congregation throughout his life. Lindsey and the church's other minister, John Disney

John Disney (Unitarian)

John Disney was an English Unitarian minister and biographical writer, initially an Anglican clergyman active against subscription to the Thirty Nine Articles.-Life:...

, became two of Johnson's most active writers. In the 1780s, Johnson continued to advocate Unitarianism and published a series of controversial writings by Priestley arguing for its legitimacy. These writings did not make Johnson much money, but they agreed with his philosophy of open debate and religious toleration. Johnson also became the publisher for the Society for Promoting the Knowledge of the Scriptures

Society for Promoting the Knowledge of the Scriptures

The Society for Promoting the Knowledge of the Scriptures was a group founded in 1783 in London, with a definite but rather constrained plan for Biblical interpretation. While in practical terms it was mainly concerned with promoting Unitarian views, it was broadly based.-Founders:The founding...

, a Unitarian group determined to release new worship materials and commentaries on the Bible. (See British and Foreign Unitarian Association#Publishing.)

Although Johnson is known for publishing Unitarian works, particularly those of Priestley, he also published the works of other Dissenters, Anglicans, and Jews. The common thread uniting his disparate religious publications was religious toleration. For example, he published the Reverend George Gregory's

George Gregory (British writer)

The Rev. George Gregory was a writer, scholar, and preacher in the 18th and early 19th-century Britain. He held a Doctor of Divinity degree.-Life:...

1787 English translation of Bishop Robert Lowth's

Robert Lowth

Robert Lowth FRS was a Bishop of the Church of England, Oxford Professor of Poetry and the author of one of the most influential textbooks of English grammar.-Life:...

seminal book on Hebrew poetry

Biblical poetry

The ancient Hebrews perceived that there were poetical portions in their sacred texts, as shown by their entitling as songs or chants such passages as Exodus 15:1-19 and Numbers 21:17-20; and a song or chant is, according to the primary meaning of the term, poetry.- Rhyme :It is often stated that...

, De Sacra Poesi Hebraeorum. Gregory published several other works with Johnson, such as Essays Historical and Moral (1785) and Sermons with Thoughts on the Composition and Delivery of a Sermon (1787). Gregory exemplified the type of author that Johnson preferred to work with: industrious and liberal-minded, but not bent on self-glorification. Yet, as Helen Braithwaite writes in her study of Johnson, his "enlightened pluralistic approach was also seen by its opponents as inherently permissive, opening the door to all forms of unhealthy questioning and scepticism, and at odds with the stable virtues of established religion and authority".

American revolution

Partially as a result of his association with British Dissenters, Johnson became involved in publishing tracts and sermons in defence of the American revolutionAmerican Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

aries. He began with Priestley's Address to Protestant Dissenters of All Denominations, on the Approaching Election of Members of Parliament (1774), which urged Dissenters to vote for candidates that guaranteed the American colonists their freedom. Johnson continued his series of anti-government, pro-American pamphlets by publishing Fast Day

Fast Day

Fast Day was a holiday observed in some parts of the United States between 1670 and 1991."A day of public fasting and prayer", it was traditionally observed in the New England states. It had its origin in days of prayer and repentance proclaimed in the early days of the American colonies by Royal...

sermons by Joshua Toulmin

Joshua Toulmin

Joshua Toulmin of Taunton, England was a noted theologian and a serial Dissenting minister of Presbyterian , Baptist , and then Unitarian congregations...

, George Walker

George Walker (Presbyterian)

George Walker was a versatile English dissenter, known as a mathematician, theologian, Fellow of the Royal Society, and activist.-Life:...

, Ebenezer Radcliff, and Newcome Cappe. Braithwaite describes these as "well-articulated critiques of government" that "were not only unusual but potentially subversive and disruptive", and she concludes that Johnson's decision to publish so much of this material indicates that he supported the political position it espoused. Moreover, Johnson published what Braithwaite calls "probably the most influential English defence of the colonists", Richard Price's

Richard Price

Richard Price was a British moral philosopher and preacher in the tradition of English Dissenters, and a political pamphleteer, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the American Revolution. He fostered connections between a large number of people, including writers of the...

Observations on the Nature of Civil Liberty (1776). Over 60,000 copies were sold in a year. In 1780 Johnson also issued the first collected political works of Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin

Dr. Benjamin Franklin was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. A noted polymath, Franklin was a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, postmaster, scientist, musician, inventor, satirist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat...

in England, a political risk as the American colonies were in rebellion by that time. Johnson did not usually reprint colonial texts—his ties to the revolution were primarily through Dissenters. Thus, the works published by Johnson emphasized both colonial independence and the rights for which Dissenters were fighting—"the right to petition for redress of grievance, the maintenance and protection of equal civil rights, and the inalienable right to liberty of conscience".

Informative texts

John Hunter (surgeon)

John Hunter FRS was a Scottish surgeon regarded as one of the most distinguished scientists and surgeons of his day. He was an early advocate of careful observation and scientific method in medicine. The Hunterian Society of London was named in his honour...

A Natural History of the Human Teeth, Part I (1771), which "elevated dentistry to the level of surgery". Johnson also supported doctors when they questioned the efficacy of cures, such as with John Millar in his Observations on Antimony (1774), which claimed that Dr James's

Robert James (physician)

Robert James was an English physician who is best known as the author of A Medicinal Dictionary, as the inventor of a popular "fever powder", and as a friend of Samuel Johnson.-Life:...

Fever Powder was ineffective. This was a risky publication for Johnson, because this patent medicine

Patent medicine

Patent medicine refers to medical compounds of questionable effectiveness sold under a variety of names and labels. The term "patent medicine" is somewhat of a misnomer because, in most cases, although many of the products were trademarked, they were never patented...

was quite popular and his fellow bookseller John Newbery

John Newbery

John Newbery was an English publisher of books who first made children's literature a sustainable and profitable part of the literary market. He also supported and published the works of Christopher Smart, Oliver Goldsmith and Samuel Johnson...

had made his fortune from selling it.

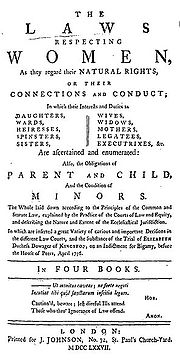

In 1777 Johnson published the remarkable Laws Respecting Women, as they Regard Their Natural Rights, which is an explication, for the layperson, of exactly what its title suggests. As Tyson comments, "the ultimate value of this book lies in its arming women with the knowledge of their legal rights in situations where they had traditionally been vulnerable because of ignorance". Johnson published Laws Respecting Women anonymously, but it is sometimes credited to Elizabeth Chudleigh Bristol

Elizabeth Pierrepont, Duchess of Kingston-upon-Hull

Elizabeth Chudleigh, Duchess of Kingston , sometimes called Countess of Bristol, was the daughter of Colonel Thomas Chudleigh , and was appointed maid of honour to Augusta, Princess of Wales, in 1743, probably through the good offices of her friend, William Pulteney, 1st Earl of Bath.-Life:Being a...

, known for her bigamous marriage to the 2nd Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull

Evelyn Pierrepont, 2nd Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull

General Evelyn Pierrepont, 2nd Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull, KG was the only son of William Pierrepont, Earl of Kingston and his wife Rachel Bayntun ....

after having previously privately married Augustus John Hervey, afterwards 3rd Earl of Bristol. This publication foreshadowed Johnson's efforts to promote works about women's issues—such as A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects , written by the 18th-century British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, is one of the earliest works of feminist philosophy. In it, Wollstonecraft responds to those educational and political theorists of the 18th...

(1792)—and his support of women writers.

Revolution in children's literature

Johnson also contributed significantly to children's literature. His publication of Barbauld'sAnna Laetitia Barbauld

Anna Laetitia Barbauld was a prominent English poet, essayist, literary critic, editor, and children's author.A "woman of letters" who published in multiple genres, Barbauld had a successful writing career at a time when female professional writers were rare...

Lessons for Children

Lessons for Children

Lessons for Children is a series of four age-adapted reading primers written by the prominent 18th-century British poet and essayist Anna Laetitia Barbauld. Published in 1778 and 1779, the books initiated a revolution in children's literature in the Anglo-American world...

(1778–79) spawned a revolution in the newly emerging genre. Its plain style, mother-child dialogues, and conversational tone inspired a generation of authors, such as Sarah Trimmer

Sarah Trimmer

Sarah Trimmer was a noted writer and critic of British children's literature in the eighteenth century...

. Johnson encouraged other women to write in this genre, such as Charlotte Smith

Charlotte Turner Smith

Charlotte Turner Smith was an English Romantic poet and novelist. She initiated a revival of the English sonnet, helped establish the conventions of Gothic fiction, and wrote political novels of sensibility....

, but his recommendation always came with a caveat of how difficult it was to write well for children. For example, he wrote to Smith, "perhaps you cannot employ your time and extraordinary talents more usefully for the public & your self [sic], than in composing books for children and young people, but I am very sensible it is extreamly [sic] difficult to acquire that simplicity of style which is their great recommendation". He also advised William Godwin

William Godwin

William Godwin was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism, and the first modern proponent of anarchism...

and his second wife, Mary Jane Clairmont, on the publication of their Juvenile Library (started in 1805). Not only did Johnson encourage the writing of British children's literature, but he also helped sponsor the translation and publication of popular French works such as Arnaud Berquin's

Arnaud Berquin

Arnaud Berquin was a French children's author.His most famous work was L'Ami des Enfans which was first translated into English, albeit bowdlerised, by Mary Stockdale and published in London in 1783-4 by Mary's father John Stockdale.The work remained popular until the middle of the nineteenth...

L'Ami des Enfans (1782–83).

In addition to books for children, Johnson published schoolbooks and textbooks for autodidacts, such as John Hewlett's

John Hewlett

John Hewlett was a prominent biblical scholar in nineteenth-century Britain.Hewlett was born in Chetnole, Dorset to Timothy Hewlett. After becoming a minister, he was admitted as a sizar to Magdalene College, Cambridge. After graduating, he established a school in Shackelford, Surrey...

Introduction to Spelling and Reading (1786), William Nicholson's

William Nicholson (chemist)

William Nicholson was a renowned English chemist and writer on "natural philosophy" and chemistry, as well as a translator, journalist, publisher, scientist, and inventor.-Early life:...

Introduction to Natural Philosophy (1782), and his friend John Bonnycastle's An Introduction to Mensuration and Practical Mathematics (1782). Johnson also published books on education and childrearing, such as Wollstonecraft's first book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters

Thoughts on the Education of Daughters

Thoughts on the education of daughters: with reflections on female conduct, in the more important duties of life is the first published work of the British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft. Published in 1787 by her friend Joseph Johnson, Thoughts is a conduct book that offers advice on female education...

(1787).

By the end of the 1770s, Johnson had become an established publisher. Writers—particularly Dissenters—sought him out, and his home started to become the centre of a radical and stimulating intellectual milieu. Because he was willing to publish multiple opinions on issues, he was respected as a publisher by writers from across the political spectrum. Johnson published many Unitarian works, but he also issued works criticizing them; although he was an abolitionist, he also published works arguing in favour of the slave trade; he supported inoculation, but he also published works critical of the practice.

1780s: Success

Literature

Once Johnson's financial situation had become secure, he began to publish literary authors, most famously the poet William CowperWilliam Cowper

William Cowper was an English poet and hymnodist. One of the most popular poets of his time, Cowper changed the direction of 18th century nature poetry by writing of everyday life and scenes of the English countryside. In many ways, he was one of the forerunners of Romantic poetry...

. Johnson issued Cowper's Poems (1782) and The Task

The Task (poem)

The Task: A Poem, in Six Books is a poem in 6000 lines of blank verse by William Cowper, usually seen as his supreme achievement. Its six books are called "The Sofa", "The Timepiece", "The Garden", "The Winter Evening", "The Winter Morning Walk" and "The Winter Walk at Noon"...

(1784) at his own expense (a generous action at a time when authors were often forced to take on the risk of publication), and was rewarded with handsome sales of both volumes. Johnson published many of Cowper's works, including the anonymous satire Anti-thelyphora (1780), which mocked the work of Cowper's own cousin, the Rev. Martin Madan, who had advocated polygamy

Polygamy

Polygamy is a marriage which includes more than two partners...

as a solution for prostitution. Johnson even edited and critiqued Cowper's poetry in manuscript, "much to the advantage of the poems" according to Cowper. In 1791, Johnson published Cowper's translations of the Homer

Homer

In the Western classical tradition Homer , is the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and is revered as the greatest ancient Greek epic poet. These epics lie at the beginning of the Western canon of literature, and have had an enormous influence on the history of literature.When he lived is...

ic epics

Epic poetry

An epic is a lengthy narrative poem, ordinarily concerning a serious subject containing details of heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation. Oral poetry may qualify as an epic, and Albert Lord and Milman Parry have argued that classical epics were fundamentally an oral poetic form...

(extensively edited and corrected by Fuseli) and three years after Cowper's death in 1800, Johnson published a biography of the poet by William Hayley

William Hayley

William Hayley was an English writer, best known as the friend and biographer of William Cowper.-Biography:...

.

Johnson never published much "creative literature"; Chard attributes this to "a lingering Calvinistic hostility to 'imaginative' literature". Most of the literary works Johnson published were religious or didactic. Some of his most popular productions in this vein were anthologies; the most famous is probably William Enfield's

William Enfield

William Enfield was a British Unitarian minister who published a bestselling book on elocution entitled The Speaker .-Life:...

The Speaker (1774), which went through multiple editions and spawned many imitations, such as Wollstonecraft's The Female Speaker.

Medical and scientific publications

Johnson continued his interest in publishing practical medical texts in the 1780s and 1790s; during the 1780s, he brought out some of his most significant works in this area. According to Johnson's friend, the physician John AikinJohn Aikin

John Aikin was an English doctor and writer.-Life:He was born at Kibworth Harcourt, Leicestershire, England, son of Dr. John Aikin, Unitarian divine, and received his elementary education at the Nonconformist academy at Warrington, where his father was a tutor. He studied medicine at the...

, he intentionally established one of his first shops on "the track of the Medical Students resorting to the Hospitals in the Borough", where they would be sure to see his wares, which helped to establish him in medical publishing. Johnson published the works of the scientist-Dissenters he met through Priestley and Barbauld, such as Thomas Beddoes

Thomas Beddoes

Thomas Beddoes , English physician and scientific writer, was born at Shifnal in Shropshire. He was a reforming practitioner and teacher of medicine, and an associate of leading scientific figures. Beddoes was a friend of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and, according to E. S...

and Thomas Young

Thomas Young (scientist)

Thomas Young was an English polymath. He is famous for having partly deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphics before Jean-François Champollion eventually expanded on his work...

. He issued the children's book on birds produced by the industrialist Samuel Galton

Samuel Galton, Jr.

Samuel "John" Galton Jr. FRS , born in Duddeston, Birmingham, England. Despite being a Quaker he was an arms manufacturer. He was a member of the Lunar Society and lived at Great Barr Hall.He married Lucy Barclay...

and the Lunar Society's

Lunar Society

The Lunar Society of Birmingham was a dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the Midlands Enlightenment, including industrialists, natural philosophers and intellectuals, who met regularly between 1765 and 1813 in Birmingham, England. At first called the Lunar Circle,...

translation of Linnaeus's System of Vegetables (1783). He also published works by James Edward Smith

James Edward Smith

Sir James Edward Smith was an English botanist and founder of the Linnean Society.Smith was born in Norwich in 1759, the son of a wealthy wool merchant. He displayed a precocious interest in the natural world...

, "the botanist who brought the Linnaean system

Binomial nomenclature

Binomial nomenclature is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin grammatical forms, although they can be based on words from other languages...

to England".

In 1784, Johnson issued John Haygarth's

John Haygarth

John Haygarth was an important 18th-century British physician who discovered new ways to prevent the spread of fever among patients and reduce the mortality rate of smallpox....

An Inquiry How to Prevent Small-Pox, which furthered the understanding and treatment of smallpox

Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease unique to humans, caused by either of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor. The disease is also known by the Latin names Variola or Variola vera, which is a derivative of the Latin varius, meaning "spotted", or varus, meaning "pimple"...

. Johnson published several subsequent works by Haygarth that promoted inoculation

Inoculation

Inoculation is the placement of something that will grow or reproduce, and is most commonly used in respect of the introduction of a serum, vaccine, or antigenic substance into the body of a human or animal, especially to produce or boost immunity to a specific disease...

(and later vaccination

Smallpox vaccine

The smallpox vaccine was the first successful vaccine to be developed. The process of vaccination was discovered by Edward Jenner in 1796, who acted upon his observation that milkmaids who caught the cowpox virus did not catch smallpox...

) for the healthy, as well as quarantining

Quarantine

Quarantine is compulsory isolation, typically to contain the spread of something considered dangerous, often but not always disease. The word comes from the Italian quarantena, meaning forty-day period....

for the sick. He also published the work of James Earle

James Earle

Sir James Earle was a celebrated British surgeon, renowned for his skill in lithotomy.Earle was born in London. After studying medicine at St. Bartholomew's Hospital, he became the institution's assistant surgeon in 1770. Due to the temporary incapacity of one of the hospital's surgeons, Earle...

, a prominent surgeon, whose significant book on lithotomy

Lithotomy

Lithotomy from Greek for "lithos" and "tomos" , is a surgical method for removal of calculi, stones formed inside certain hollow organs, such as the kidneys , bladder , and gallbladder , that cannot exit naturally through the urinary system or biliary tract...

was illustrated by William Blake

William Blake

William Blake was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of both the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age...

, and Matthew Baillie's

Matthew Baillie

Matthew Baillie was a Scottish physician and pathologist.-Life:...

Morbid Anatomy (1793), "the first text of pathology devoted to that science exclusively by systematic arrangement and design".

Not only did Johnson publish the majority of Priestley's theological works, but he also published his scientific works, such as Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air

Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air

Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air is a six-volume work published by 18th-century British polymath Joseph Priestley which reports a series of his experiments on "airs" or gases, most notably his discovery of oxygen gas .-Airs:While working as a companion for Lord Shelburne,...

(1774–77) in which Priestley announced his discovery of oxygen

Oxygen

Oxygen is the element with atomic number 8 and represented by the symbol O. Its name derives from the Greek roots ὀξύς and -γενής , because at the time of naming, it was mistakenly thought that all acids required oxygen in their composition...

. Johnson also published the works of Carl Wilhelm Scheele

Carl Wilhelm Scheele

Carl Wilhelm Scheele was a German-Swedish pharmaceutical chemist. Isaac Asimov called him "hard-luck Scheele" because he made a number of chemical discoveries before others who are generally given the credit...

and Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier , the "father of modern chemistry", was a French nobleman prominent in the histories of chemistry and biology...

, both of whom made their own claims of having discovered oxygen. When Lavoisier began to publish works in France on the "new chemistry

Chemical Revolution

The chemical revolution, also called the first chemical revolution, denotes the reformulation of chemistry based on the Law of Conservation of Matter and the oxygen theory of combustion. It was centered on the work of French chemist Antoine Lavoisier...

" that he had developed (which included today's modern notions of element

Chemical element

A chemical element is a pure chemical substance consisting of one type of atom distinguished by its atomic number, which is the number of protons in its nucleus. Familiar examples of elements include carbon, oxygen, aluminum, iron, copper, gold, mercury, and lead.As of November 2011, 118 elements...

and compound

Chemical compound

A chemical compound is a pure chemical substance consisting of two or more different chemical elements that can be separated into simpler substances by chemical reactions. Chemical compounds have a unique and defined chemical structure; they consist of a fixed ratio of atoms that are held together...

), Johnson had these translated and printed immediately, despite his association with Priestley who argued strenuously against Lavoisier's new system. Johnson was the first to publish an English edition of Lavoisier's early writings on chemistry and he kept up with the ongoing debate. These works did well for Johnson and increased his visibility among men of science.

Johnson Circle and dinners

With time, Johnson's home became a nexus for radical thinkers, who appreciated his open-mindedness, generous spirit, and humanitarianism. Although usually separated by geography, such thinkers would meet and debate with one another at Johnson's house in London, often over dinner. This network not only brought authors into contact with each other, it also brought new writers to Johnson's business. For example, Priestley introduced John NewtonJohn Newton

John Henry Newton was a British sailor and Anglican clergyman. Starting his career on the sea at a young age, he became involved with the slave trade for a few years. After experiencing a religious conversion, he became a minister, hymn-writer, and later a prominent supporter of the abolition of...

to Johnson, Newton brought John Hewlett

John Hewlett

John Hewlett was a prominent biblical scholar in nineteenth-century Britain.Hewlett was born in Chetnole, Dorset to Timothy Hewlett. After becoming a minister, he was admitted as a sizar to Magdalene College, Cambridge. After graduating, he established a school in Shackelford, Surrey...

, and Hewlett invited Mary Wollstonecraft, who in turn attracted Mary Hays

Mary Hays

Mary Hays was an English novelist and feminist.- Early years :Mary Hays was born in Southwark, London on Oct. 13, 1759. Almost nothing is known of her first 17 years. In 1779 she fell in love with John Eccles who lived on Gainsford Street, where she also lived. Their parents opposed the match but...

who brought William Godwin

William Godwin

William Godwin was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism, and the first modern proponent of anarchism...

. With this broad network of acquaintances and reputation for free-thinking publications, Johnson became the favourite publisher of a generation of writers and thinkers. By bringing inventive, thoughtful people together, he "stood at the very heart of British intellectual life" for over twenty years. Importantly, Johnson's circle was not made up entirely of either liberals or radicals. Chard emphasizes that it "was held together less by political liberalism than by a common interest in ideas, free enquiry, and creative expression in various fields".

Thomas Percival

Thomas Percival FRS FRSE FSA was an English physician and author, best known for crafting perhaps the first modern code of medical ethics...

, Barbauld, Aikin, and Enfield. Later, more radicals would join, including Wollstonecraft, Wakefield, John Horne Tooke

John Horne Tooke

John Horne Tooke was an English politician and philologist.-Early life and work:He was born in Newport Street, Long Acre, Westminster, the third son of John Horne, a poulterer in Newport Market. As a youth at Eton College, Tooke described his father to friends as a "turkey merchant"...

, and Thomas Christie

Thomas Christie

Thomas Christie was a radical political writer during the late 18th century. He was one of the two original founders of the important liberal journal, the Analytical Review....

.

Johnson's dinners became legendary and it appears, from evidence collected from diaries, that a large number of people attended each one. Although there were few regulars, except perhaps for Johnson's close London friends (Fuseli, Bonnycastle and, later, Godwin), the large number of luminaries, such as Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine

Thomas "Tom" Paine was an English author, pamphleteer, radical, inventor, intellectual, revolutionary, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States...

, who attended attests to the reputation of these dinners. The enjoyment and intellectual stimulation that these dinners provided is evidenced by the numerous references to them in diaries and letters. Barbauld wrote to her brother in 1784 that "our evenings, particularly at Johnson's, were so truly social and lively, that we protracted them sometimes till—but I am not telling tales." At one dinner in 1791, Godwin records that the conversation focused on "monarch, Tooke, [Samuel] Johnson, Voltaire, pursuits, and religion" [emphasis Godwin's]. Although the conversation was stimulating, Johnson apparently only served his guests simple meals, such as boiled cod, veal, vegetables, and rice pudding

Rice pudding

Rice pudding is a dish made from rice mixed with water or milk and sometimes other ingredients such as cinnamon and raisins. Different variants are used for either desserts or dinners. When used as a dessert, it is commonly combined with a sweetener such as sugar.-Rice pudding around the world:Rice...

. Many of the people that met at these dinners became fast friends, as did Fuseli and Bonnycastle; Godwin and Wollstonecraft eventually married.

Friendship with Mary Wollstonecraft

The friendship between Johnson and Mary Wollstonecraft was pivotal in both of their lives, and illustrates the active role that Johnson played in developing writing talent. In 1787, Wollstonecraft was in financial straits: she had just been let go from a governessGoverness

A governess is a girl or woman employed to teach and train children in a private household. In contrast to a nanny or a babysitter, she concentrates on teaching children, not on meeting their physical needs...

position in Ireland and had moved back to London. She had resolved to be an author in an era that afforded few professional opportunities to women. After Unitarian schoolteacher John Hewlett

John Hewlett

John Hewlett was a prominent biblical scholar in nineteenth-century Britain.Hewlett was born in Chetnole, Dorset to Timothy Hewlett. After becoming a minister, he was admitted as a sizar to Magdalene College, Cambridge. After graduating, he established a school in Shackelford, Surrey...

suggested to Wollstonecraft that she submit her writings to Johnson, an enduring and mutually supportive relationship blossomed between Johnson and Wollstonecraft. He dealt with her creditors, secured lodgings for her, and advanced payment on her first book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters

Thoughts on the Education of Daughters

Thoughts on the education of daughters: with reflections on female conduct, in the more important duties of life is the first published work of the British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft. Published in 1787 by her friend Joseph Johnson, Thoughts is a conduct book that offers advice on female education...

(1787), and her first novel, Mary: A Fiction

Mary: A Fiction

Mary: A Fiction is the only complete novel by the 18th-century British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft. It tells the tragic story of a heroine's successive "romantic friendships" with a woman and a man...

(1788). Johnson included Wollstonecraft in the exalted company of his weekly soirées, where she met famous personages, such as Thomas Paine and her future husband, William Godwin. Wollstonecraft, who is believed to have written some 200 articles for his periodical, the Analytical Review

Analytical Review

The Analytical Review was a periodical established in London in 1788 by the publisher Joseph Johnson and the writer Thomas Christie. Part of the Republic of Letters, it was a gadfly publication, which offered readers summaries and analyses of the many new publications issued at the end of the...

, regarded Johnson as a true friend. After a disagreement, she sent him the following note the next morning:

You made me very low-spirited last night, by your manner of talking—You are my only friend—the only person I am intimate with.—I never had a father, or a brother—you have been both to me, ever since I knew you—yet I have sometimes been very petulant.—I have been thinking of those instances of ill-humour and quickness, and they appeared like crimes. Yours sincerely, Mary.

Johnson offered Wollstonecraft work as a translator, prompting her to learn French and German. More importantly, Johnson provided encouragement at crucial moments during the writing of her seminal political treatises A Vindication of the Rights of Men

A Vindication of the Rights of Men

A Vindication of the Rights of Men, in a Letter to the Right Honourable Edmund Burke; Occasioned by His Reflections on the Revolution in France is a political pamphlet, written by the 18th-century British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, which attacks aristocracy and advocates republicanism...

(1790) and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects , written by the 18th-century British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, is one of the earliest works of feminist philosophy. In it, Wollstonecraft responds to those educational and political theorists of the 18th...

(1792).

1790s: Years of radicalism

Society for Constitutional Information

Founded in 1780 by Major John Cartwright to promote parliamentary reform, the Society for Constitutional Information flourished until 1783, but thereafter made little headway...

, which was attempting to reform Parliament; he published works defending Dissenters

English Dissenters

English Dissenters were Christians who separated from the Church of England in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries.They originally agitated for a wide reaching Protestant Reformation of the Established Church, and triumphed briefly under Oliver Cromwell....

after the religiously motivated Birmingham Riots

Priestley Riots

The Priestley Riots took place from 14 July to 17 July 1791 in Birmingham, England; the rioters' main targets were religious Dissenters, most notably the politically and theologically controversial Joseph Priestley...

in 1791; and he testified on behalf of those arrested during the 1794 Treason Trials

1794 Treason Trials

The 1794 Treason Trials, arranged by the administration of William Pitt, were intended to cripple the British radical movement of the 1790s. Over thirty radicals were initially arrested; three were tried for high treason: Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke and John Thelwall...

. Johnson published works championing the rights of slaves, Jews, women, prisoners, Dissenters, chimney sweep

Chimney sweep

A chimney sweep is a worker who clears ash and soot from chimneys. The chimney uses the pressure difference caused by a hot column of gas to create a draught and draw air over the hot coals or wood enabling continued combustion. Chimneys may be straight or contain many changes of direction. During...

s, abused animals, university students forbidden from marrying, victims of press gangs

Impressment

Impressment, colloquially, "the Press", was the act of taking men into a navy by force and without notice. It was used by the Royal Navy, beginning in 1664 and during the 18th and early 19th centuries, in wartime, as a means of crewing warships, although legal sanction for the practice goes back to...

, and those unjustly accused of violating the game law

Game law

Game laws are statutes which regulate the right to pursue and take or kill certain kinds of fish and wild animal . Their scope can include the following: restricting the days to harvest fish or game, restricting the number of animals per person, restricting species harvested, and limiting weapons...

s.

Political literature became Johnson's mainstay in the 1790s: he published 118 works, which amounted to 57% of his total political output. As Chard notes, "hardly a year went by without at least one anti-war and one anti-slave trade publication from Johnson". In particular, Johnson published abolitionist

Abolitionism

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery.In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first...

works, such as minister and former slave-ship captain John Newton's

John Newton

John Henry Newton was a British sailor and Anglican clergyman. Starting his career on the sea at a young age, he became involved with the slave trade for a few years. After experiencing a religious conversion, he became a minister, hymn-writer, and later a prominent supporter of the abolition of...

Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade (1788), Barbauld's Epistle to William Wilberforce (1791), and Captain John Gabriel Stedman's

John Gabriel Stedman

John Gabriel Stedman was a distinguished British–Dutch soldier and noted author. He was born in the Netherlands in 1744 to Robert Stedman, a Scot and an officer in Holland's Scots Brigade, and his wife of Dutch noble lineage, Antoinetta Christina van Ceulen. He lived most of his childhood in...

Narrative, of a Five Years' Expedition, Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam (1796) (with illustrations by Blake). Most importantly he helped organize the publication of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African, first published in 1789, is the autobiography of Olaudah Equiano.-Plot introduction:...

(1789), the autobiography of former slave Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano also known as Gustavus Vassa, was a prominent African involved in the British movement towards the abolition of the slave trade. His autobiography depicted the horrors of slavery and helped influence British lawmakers to abolish the slave trade through the Slave Trade Act of 1807...

.

Later in the decade, Johnson focused on works about the French revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

, concentrating on those from France itself, but he also published commentary from America by Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

and James Monroe

James Monroe

James Monroe was the fifth President of the United States . Monroe was the last president who was a Founding Father of the United States, and the last president from the Virginia dynasty and the Republican Generation...

. Johnson's determination to publish political and revolutionary works, however, fractured his Circles: Dissenters were alienated from Anglicans during efforts to repeal the Test

Test Act

The Test Acts were a series of English penal laws that served as a religious test for public office and imposed various civil disabilities on Roman Catholics and Nonconformists...

and Corporation Acts

Corporation Act 1661

The Corporation Act of 1661 is an Act of the Parliament of England . It belongs to the general category of test acts, designed for the express purpose of restricting public offices in England to members of the Church of England....

and moderates split from radicals during the French revolution. Johnson lost customers, friends, and writers, including the children's author Sarah Trimmer

Sarah Trimmer

Sarah Trimmer was a noted writer and critic of British children's literature in the eighteenth century...

. Braithwaite speculates that Johnson also lost business due to his willingness to put out works that promoted the "challenging new historicist versions of the scriptures", such as those by Alexander Geddes

Alexander Geddes

Alexander Geddes was a Scottish theologian and scholar.He was born at Ruthven, Banffshire, of Roman Catholic parentage, and educated for the priesthood at the local seminary of Scalan, and at Paris; he became a priest in his native county.His translation of the Satires of Horace made him known as...

.

Scholars are, however, careful to note that except for Benjamin Franklin's

Benjamin Franklin

Dr. Benjamin Franklin was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. A noted polymath, Franklin was a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, postmaster, scientist, musician, inventor, satirist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat...

works and Joel Barlow's

Joel Barlow

Joel Barlow was an American poet, diplomat and politician. In his own time, Barlow was well-known for the epic Vision of Columbus. Modern readers may be more familiar with "The Hasty Pudding"...

pamphlets, Johnson did not print anything truly revolutionary. He refused to publish Paine's Rights of Man

Rights of Man

Rights of Man , a book by Thomas Paine, posits that popular political revolution is permissible when a government does not safeguard its people, their natural rights, and their national interests. Using these points as a base it defends the French Revolution against Edmund Burke's attack in...

and William Blake's

William Blake

William Blake was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of both the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age...

The French Revolution, for example. It is almost impossible to determine Johnson's own personal political beliefs from the historical record. Marilyn Gaull argues that "if Johnson were radical, indeed if he had any political affiliation ... it was accidental". Gaull describes Johnson's "liberalism" as that "of [a] generous, open, fair-minded, unbiased defender of causes lost and won". His real contribution, she contends, was "as a disseminator of contemporary knowledge, especially science, medicine, and pedagogical practice" and as an advocate for a popular style. He encouraged all of his writers to use "plain syntax and colloquial diction" so that "self-educated readers" could understand his publications. Johnson's association with writers such as Godwin has previously been used to emphasize his radicalism, but Braithwaite points out that Godwin only became a part of Johnson's Circle late in the 1790s; Johnson's closest friends—Priestley, Fuseli, and Bonnycastle—were much more politically moderate. Johnson was not a populist or democratic bookseller: he catered to the self-educating middle class.

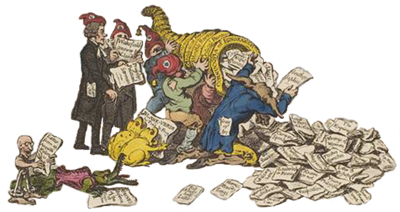

Revolution controversy

In 1790, with the publication of his Reflections on the Revolution in FranceReflections on the Revolution in France

Reflections on the Revolution in France , by Edmund Burke, is one of the best-known intellectual attacks against the French Revolution...

, philosopher and statesman Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke PC was an Irish statesman, author, orator, political theorist and philosopher who, after moving to England, served for many years in the House of Commons of Great Britain as a member of the Whig party....

launched the first volley of a vicious pamphlet

Pamphlet

A pamphlet is an unbound booklet . It may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths , or it may consist of a few pages that are folded in half and saddle stapled at the crease to make a simple book...

war in what became known as the Revolution Controversy

Revolution Controversy

The Revolution Controversy was a British debate over the French Revolution, lasting from 1789 through 1795. A pamphlet war began in earnest after the publication of Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France , which surprisingly supported the French aristocracy...

. Because he had supported the American Revolution

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

, friends and enemies alike expected him to support the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

. His book, which decries the French Revolution, therefore came as a shock to nearly everyone. Priced at an expensive five shilling

Shilling

The shilling is a unit of currency used in some current and former British Commonwealth countries. The word shilling comes from scilling, an accounting term that dates back to Anglo-Saxon times where it was deemed to be the value of a cow in Kent or a sheep elsewhere. The word is thought to derive...

s, it still sold over 10,000 copies in a few weeks. Reformers, particularly Dissenters, felt compelled to reply. Johnson's periodical, the Analytical Review

Analytical Review

The Analytical Review was a periodical established in London in 1788 by the publisher Joseph Johnson and the writer Thomas Christie. Part of the Republic of Letters, it was a gadfly publication, which offered readers summaries and analyses of the many new publications issued at the end of the...

, published a summary and review of Burke's work within a couple of weeks of its publication. Two weeks later, Wollstonecraft responded to Burke with her Vindication of the Rights of Men

A Vindication of the Rights of Men

A Vindication of the Rights of Men, in a Letter to the Right Honourable Edmund Burke; Occasioned by His Reflections on the Revolution in France is a political pamphlet, written by the 18th-century British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, which attacks aristocracy and advocates republicanism...

. In issuing one of the first and cheapest replies to Burke (Vindication cost only one shilling), Johnson put himself at some risk. Thomas Cooper, who had also written a response to Burke, was later informed by the Attorney General that "although there was no exception to be taken to his pamphlet when in the hands of the upper classes, yet the government would not allow it to appear at a price which would insure its circulation among the people". Many others soon joined in the fray and Johnson remained at the centre of the maelstrom. By Braithwaite's count, Johnson published or sold roughly a quarter of the works responding to Burke within the following year.

Thomas Paine

Thomas "Tom" Paine was an English author, pamphleteer, radical, inventor, intellectual, revolutionary, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States...

Rights of Man

Rights of Man

Rights of Man , a book by Thomas Paine, posits that popular political revolution is permissible when a government does not safeguard its people, their natural rights, and their national interests. Using these points as a base it defends the French Revolution against Edmund Burke's attack in...

. Johnson originally agreed to publish the controversial work, but he backed out later for unknown reasons and J. S. Jordan distributed it (and was subsequently tried and imprisoned for its publication). Braithwaite speculates that Johnson did not agree with Paine's radical republican

Republicanism

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context...

statements and was more interested in promoting the rights of Dissenters outlined in the other works he published. After the initial risk was taken by Jordan, however, Johnson published Paine's work in an expensive edition, which was unlikely to be challenged at law. Yet, when Paine was himself later arrested, Johnson helped raise funds to bail him out and hid him from the authorities. A contemporary satire

Satire

Satire is primarily a literary genre or form, although in practice it can also be found in the graphic and performing arts. In satire, vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, ideally with the intent of shaming individuals, and society itself, into improvement...

suggested that Johnson saved Paine from imprisonment:

Alarmed at the popular appeal of Paine's Rights of Man, the king issued a proclamation against seditious

Sedition

In law, sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that is deemed by the legal authority to tend toward insurrection against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent to lawful authority. Sedition may include any...

writings in May 1792. Booksellers and printers bore the brunt of this law, the effects of which came to a head in the 1794 Treason Trials

1794 Treason Trials

The 1794 Treason Trials, arranged by the administration of William Pitt, were intended to cripple the British radical movement of the 1790s. Over thirty radicals were initially arrested; three were tried for high treason: Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke and John Thelwall...

. Johnson testified, publicly distancing himself from Paine and Barlow, despite the fact that the defendants were received sympathetically by the juries.

Poetry

During the 1790s alone, Johnson published 103 volumes of poetry—37% of his entire output in the genre. The bestselling poetical works of Cowper and Erasmus DarwinErasmus Darwin

Erasmus Darwin was an English physician who turned down George III's invitation to be a physician to the King. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave trade abolitionist,inventor and poet...

enriched Johnson's firm. Darwin's innovative The Botanic Garden

The Botanic Garden

The Botanic Garden is a set of two poems, The Economy of Vegetation and The Loves of the Plants, by the British poet and naturalist Erasmus Darwin. The Economy of Vegetation celebrates technological innovation, scientific discovery and offers theories concerning contemporary scientific questions,...

(1791) was particularly successful: Johnson paid him 1,000 guineas

Guinea (British coin)

The guinea is a coin that was minted in the Kingdom of England and later in the Kingdom of Great Britain and the United Kingdom between 1663 and 1813...

before it was ever released and bought the copyright from him for £

Pound sterling