Religious toleration

Encyclopedia

There is only one verb 'to tolerate' and one adjective 'tolerant', but the two nouns 'tolerance' and 'toleration' have evolved slightly different meanings. Tolerance is an attitude of mind that implies non-judgmental acceptance of different lifestyles or beliefs, whereas toleration implies putting up with something that one disapproves of.

Historically, most incidents and writings pertaining to toleration involve the status of minority and dissenting viewpoints in relation to a dominant state religion

State religion

A state religion is a religious body or creed officially endorsed by the state...

. In the twentieth century and after, analysis of the doctrine of toleration has been expanded to include political and ethnic groups, homosexuals and other minorities, and human rights

Human rights

Human rights are "commonly understood as inalienable fundamental rights to which a person is inherently entitled simply because she or he is a human being." Human rights are thus conceived as universal and egalitarian . These rights may exist as natural rights or as legal rights, in both national...

embodies the principle of legally enforced toleration.

In antiquity

As reported in the Old TestamentOld Testament

The Old Testament, of which Christians hold different views, is a Christian term for the religious writings of ancient Israel held sacred and inspired by Christians which overlaps with the 24-book canon of the Masoretic Text of Judaism...

, the Persian king Cyrus the Great

Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia , commonly known as Cyrus the Great, also known as Cyrus the Elder, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Under his rule, the empire embraced all the previous civilized states of the ancient Near East, expanded vastly and eventually conquered most of Southwest Asia and much...

was believed to have released the Jews from captivity in 539–530 BC, and permitted their return to their homeland.

The Hellenistic city of Alexandria

Alexandria

Alexandria is the second-largest city of Egypt, with a population of 4.1 million, extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the north central part of the country; it is also the largest city lying directly on the Mediterranean coast. It is Egypt's largest seaport, serving...

, founded 331 BC, contained a large Jewish community which lived in peace with equivalently sized Greek and Egyptian populations. According to Michael Walzer

Michael Walzer

Michael Walzer is a prominent American political philosopher and public intellectual. A professor emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, he is co-editor of Dissent, an intellectual magazine that he has been affiliated with since his years as an undergraduate at...

, the city provided "a useful example of what we might think of as the imperial version of multiculturalism."

The Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

encouraged conquered peoples to continue worshipping their own gods. "An important part of Roman propaganda was its invitation to the gods of conquered territories to enjoy the benefits of worship within the imperium." Christians were singled out for persecution because of their own rejection of Roman pantheism and refusal to honor the emperor as a god. In 311 AD, Roman Emperor Galerius

Galerius

Galerius , was Roman Emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sassanid Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across the Danube against the Carpi, defeating them in 297 and 300...

issued a general edict of toleration

Edict of Toleration by Galerius

The Edict of Toleration by Galerius was issued in 311 by the Roman Tetrarchy of Galerius, Constantine and Licinius, officially ending the Diocletian persecution of Christianity....

of Christianity, in his own name and in those of Licinius

Licinius

Licinius I , was Roman Emperor from 308 to 324. Co-author of the Edict of Milan that granted official toleration to Christians in the Roman Empire, for the majority of his reign he was the rival of Constantine I...

and Constantine I

Constantine I

Constantine the Great , also known as Constantine I or Saint Constantine, was Roman Emperor from 306 to 337. Well known for being the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity, Constantine and co-Emperor Licinius issued the Edict of Milan in 313, which proclaimed religious tolerance of all...

(who converted to Christianity the following year).

Biblical sources of toleration

In the Old Testament, the books of Exodus, LeviticusLeviticus

The Book of Leviticus is the third book of the Hebrew Bible, and the third of five books of the Torah ....

and Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy

The Book of Deuteronomy is the fifth book of the Hebrew Bible, and of the Jewish Torah/Pentateuch...

make similar statements about the treatment of strangers. For example, Exodus 22:21 says: "Thou shalt neither vex a stranger, nor oppress him: for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt". These texts are frequently used in sermons to plead for compassion and tolerance of those who are different than us and less powerful. Julia Kristeva

Julia Kristeva

Julia Kristeva is a Bulgarian-French philosopher, literary critic, psychoanalyst, sociologist, feminist, and, most recently, novelist, who has lived in France since the mid-1960s. She is now a Professor at the University Paris Diderot...

elucidated a philosophy of political and religious toleration based on all of our mutual identities as strangers.

The New Testament Parable of the Tares, which speaks of the difficulty of distinguishing wheat from weeds before harvest time, has also been invoked in support of religious toleration. In his "Letter to Bishop Roger of Chalons", Bishop Wazo of Liege

Wazo of Liège

Wazo of Liège was bishop of Liège from 1041 to 1048, and a significant educator and theologian. His life was chronicled by his contemporary Anselm of Liège.During this period Liège became known as an educational center...

(c. 985–1048 AD) relied on the parable to argue that "the church should let dissent grow with orthodoxy until the Lord comes to separate and judge them".

Roger Williams

Roger Williams (theologian)

Roger Williams was an English Protestant theologian who was an early proponent of religious freedom and the separation of church and state. In 1636, he began the colony of Providence Plantation, which provided a refuge for religious minorities. Williams started the first Baptist church in America,...

, a Baptist theologian and founder of Rhode Island, used this parable to support government toleration of all of the "weeds" (heretics) in the world, because civil persecution often inadvertently hurts the "wheat" (believers) too. Instead, Williams believed it was God's duty to judge in the end, not man's. This parable lent further support to Williams' Biblical philosophy of a wall of separation between church and state as described in his 1644 book, The Bloody Tenent of Persecution.

In the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance

In the Middle AgesMiddle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

, there were instances of toleration of particular groups. The Latin concept tolerantia was a "highly-developed political and judicial concept in mediaeval scholastic theology and canon law." Tolerantia was used to "denote the self-restraint of a civil power in the face of" outsiders, like infidels, Muslims or Jews, but also in the face of social groups like prostitutes and lepers. Later, theologians belonging, or reacting, to, the Protestant Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

, began discussion of the circumstances under which dissenting religious thought should be permitted. Toleration "as a government-sanctioned practice" in Christian countries, "the sense on which most discussion of the phenomenon relies — is not attested before the sixteenth century".

Tolerance of the Jews

In 1348, Pope Clement VIPope Clement VI

Pope Clement VI , bornPierre Roger, the fourth of the Avignon Popes, was pope from May 1342 until his death in December of 1352...

(1291–1352) issued a bull

Papal bull

A Papal bull is a particular type of letters patent or charter issued by a Pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the bulla that was appended to the end in order to authenticate it....

pleading with Catholics not to murder Jews, whom they blamed for the Black Death. He noted that Jews died of the plague like anyone else, and that the disease also flourished in areas where there were no Jews. Christians who blamed and killed Jews had been “seduced by that liar, the Devil”. He took Jews under his personal protection at Avignon, but his calls for other clergy to do so failed to be heeded.

Johann Reuchlin

Johann Reuchlin

Johann Reuchlin was a German humanist and a scholar of Greek and Hebrew. For much of his life, he was the real centre of all Greek and Hebrew teaching in Germany.-Early life:...

(1455–1522) was a German humanist and a scholar of Greek and Hebrew who opposed efforts by Johannes Pfefferkorn

Johannes Pfefferkorn

Johannes Pfefferkorn was a Jewish-born, German Catholic theologian and writer who converted from Judaism. Pfefferkorn actively preached against the Jews and attempted to destroy copies of the Talmud, and engaged in a long running pamphleteering battle with Johann Reuchlin.-Early life:Born a Jew,...

, backed by the Dominicans of Cologne, to confiscate all religious texts from the Jews as a first step towards their forcible conversion to the Catholic religion.

Despite occasional spontaneous episodes of pogroms and killings, as during the Black Death, Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

was a relatively tolerant home for the Jews in the medieval period. In 1264, the Statute of Kalisz

Statute of Kalisz

The General Charter of Jewish Liberties known as the Statute of Kalisz was issued by the Duke of Greater Poland Boleslaus the Pious on September 8, 1264 in Kalisz...

guaranteed safety, personal liberties, freedom of religion

Freedom of religion

Freedom of religion is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance; the concept is generally recognized also to include the freedom to change religion or not to follow any...

, trade, and travel to Jews. By the mid-16th century, Poland was home to 80% of the world's Jewish population. Jewish worship was officially recognized, with a Chief Rabbi originally appointed by the monarch. Jewish property ownership was also protected for much of the period, and Jews entered into business partnerships with members of the nobility.

Vladimiri

Paulus Vladimiri (ca. 1370–1435) was a Polish scholar and rector who at the Council of ConstanceCouncil of Constance

The Council of Constance is the 15th ecumenical council recognized by the Roman Catholic Church, held from 1414 to 1418. The council ended the Three-Popes Controversy, by deposing or accepting the resignation of the remaining Papal claimants and electing Pope Martin V.The Council also condemned and...

in 1414, presented a thesis, Tractatus de potestate papae et imperatoris respectu infidelium (Treatise on the Power of the Pope and the Emperor Respecting Infidels). In it he argued that pagan and Christian nations could coexist in peace and criticized the Teutonic Order for its wars of conquest of native non-Christian peoples in Prussia and Lithuania. Vladimiri strongly supported the idea of conciliarism and pioneered the notion of peaceful coexistence among nations – a forerunner of modern theories of human rights. Throughout his political, diplomatic and university career, he expressed the view that a world guided by the principles of peace and mutual respect among nations was possible and that pagan nations had a right to peace and to possession of their own lands.

Erasmus

Desiderius ErasmusDesiderius Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus , known as Erasmus of Rotterdam, was a Dutch Renaissance humanist, Catholic priest, and a theologian....

Roterodamus (1466–1536), was a Dutch Renaissance humanist and Catholic whose works laid a foundation for religious toleration. For example, in De libero arbitrio, opposing certain views of Martin Luther

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

, Erasmus noted that religious disputants should be temperate in their language, "because in this way the truth, which is often lost amidst too much wrangling may be more surely perceived." Gary Remer writes, "Like Cicero

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero , was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.He introduced the Romans to the chief...

, Erasmus concludes that truth is furthered by a more harmonious relationship between interlocutors." Although Erasmus did not oppose the punishment of heretics, in individual cases he generally argued for moderation and against the death penalty. He wrote, "It is better to cure a sick man than to kill him."

More

Sir Thomas More (1478–1535), Catholic Lord Chancellor of King Henry VIII and author, described a world of almost complete religious toleration in UtopiaUtopia (book)

Utopia is a work of fiction by Thomas More published in 1516...

(1516), in which the Utopians "can hold various religious beliefs without persecution from the authorities." However, More's work is subject to various interpretations, and it is not clear that he felt that earthly society should be conducted the same way as in Utopia. Thus, in his three years as Lord Chancellor, More actively approved of the persecution of those who sought to undermine the Catholic faith in England.

Castellio

Sebastian CastellioSebastian Castellio

Sebastian Castellio was a French preacher and theologian; and one of the first Reformed Christian proponents of religious toleration, freedom of conscience and thought....

(1515–1563) was a French Protestant theologian who in 1554 published under a pseudonym the pamphlet Whether heretics should be persecuted (De haereticis, an sint persequendi) criticizing John Calvin

John Calvin

John Calvin was an influential French theologian and pastor during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of Christian theology later called Calvinism. Originally trained as a humanist lawyer, he broke from the Roman Catholic Church around 1530...

's execution of Michael Servetus

Michael Servetus

Michael Servetus was a Spanish theologian, physician, cartographer, and humanist. He was the first European to correctly describe the function of pulmonary circulation...

: "When Servetus fought with reasons and writings, he should have been repulsed by reasons and writings." Castellio concluded: "We can live together peacefully only when we control our intolerance. Even though there will always be differences of opinion from time to time, we can at any rate come to general understandings, can love one another, and can enter the bonds of peace, pending the day when we shall attain unity of faith." Castellio is remembered for the often quoted statement, "To kill a man is not to protect a doctrine, but it is to kill a man.

Bodin

Jean BodinJean Bodin

Jean Bodin was a French jurist and political philosopher, member of the Parlement of Paris and professor of law in Toulouse. He is best known for his theory of sovereignty; he was also an influential writer on demonology....

(1530–1596) was a French Catholic jurist and political philosopher. His Latin work Colloquium heptaplomeres de rerum sublimium arcanis abditis ("The Colloqium of the Seven") portrays a conversation about the nature of truth between seven cultivated men from diverse religious or philosophical backgrounds: a natural philosopher, a Calvinist, a Muslim, a Roman Catholic, a Lutheran, a Jew, and a skeptic. All agree to live in mutual respect and tolerance.

Montaigne

Michel de MontaigneMichel de Montaigne

Lord Michel Eyquem de Montaigne , February 28, 1533 – September 13, 1592, was one of the most influential writers of the French Renaissance, known for popularising the essay as a literary genre and is popularly thought of as the father of Modern Skepticism...

(1533–1592), French Catholic essayist and statesman, moderated between the Catholic and Protestant sides in the Wars of Religion. Montaigne's theory of skepticism led to the conclusion that we cannot precipitously decide the error of other's views. Montaigne wrote in his famous "Essais": "It is putting a very high value on one's conjectures, to have a man roasted alive because of them...To kill people, there must be sharp and brilliant clarity."

Edict of Torda

In 1568, King John II Sigismund of Hungary, encouraged by his Unitarian Minister Francis David (Dávid Ferenc), issued the Edict of Torda decreeing religious toleration.Maximilian II

In 1571, Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian IIMaximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor

Maximilian II was king of Bohemia and king of the Romans from 1562, king of Hungary and Croatia from 1563, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation from 1564 until his death...

granted religious toleration to the nobles of Lower Austria, their families and workers.

The Warsaw Confederation

Poland has a long tradition of religious freedom. The right to worship freely was a basic right given to all inhabitants of the Commonwealth throughout the 15th and early 16th century, however, complete freedom of religion was officially recognized in Poland in 1573 during the Warsaw ConfederationWarsaw Confederation

The Warsaw Confederation , an important development in the history of Poland and Lithuania that extended religious tolerance to nobility and free persons within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. , is considered the formal beginning of religious freedom in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and...

. Poland kept religious freedom laws during an era when religious persecution was an everyday occurrence in the rest of Europe.

The Warsaw Confederation

Warsaw Confederation

The Warsaw Confederation , an important development in the history of Poland and Lithuania that extended religious tolerance to nobility and free persons within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. , is considered the formal beginning of religious freedom in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and...

of 1573 was a private compact signed by representatives of all the major religions in Polish and Lithuanian society, in which they pledged each other mutual support and tolerance. The confederation was incorporated into the Henrican articles, which constituted a virtual Polish constitution.

Edict of Nantes

The Edict of NantesEdict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes, issued on 13 April 1598, by Henry IV of France, granted the Calvinist Protestants of France substantial rights in a nation still considered essentially Catholic. In the Edict, Henry aimed primarily to promote civil unity...

, issued on April 13, 1598, by Henry IV of France

Henry IV of France

Henry IV , Henri-Quatre, was King of France from 1589 to 1610 and King of Navarre from 1572 to 1610. He was the first monarch of the Bourbon branch of the Capetian dynasty in France....

, granted the Protestants of France (also known as Huguenots) substantial rights in a nation still considered essentially Catholic. The main concern was civil unity; the Edict separated civil from religious unity, treated some Protestants for the first time as more than mere schismatics and heretics, and opened a path for secularism and tolerance. In offering general freedom of conscience to individuals, the edict offered many specific concessions to the Protestants, such as amnesty and the reinstatement of their civil rights, including the right to work in any field or for the State and to bring grievances directly to the king. It marked the end of the religious wars that tore apart the population of France during the second half of the 16th century.

The Edict of Nantes was revoked in 1685 by King Louis XIV, leading to a renewal of the persecution of Protestants in France.

In the Enlightenment

Beginning in the EnlightenmentAge of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

commencing in the 1600s, politicians and commentators began formulating theories of religious toleration and basing legal codes on the concept. A distinction began to develop between civil tolerance, concerned with "the policy of the state towards religious dissent"., and ecclesiastical tolerance, concerned with the degree of diversity tolerated within a particular church.

Milton

John MiltonJohn Milton

John Milton was an English poet, polemicist, a scholarly man of letters, and a civil servant for the Commonwealth of England under Oliver Cromwell...

(1608–1674), English Protestant poet and essayist, called in the Aeropagitica for "the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties" (applied however, only to the conflicting Protestant sects, and not to atheists, Jews, Moslems or even Catholics). "Milton argued for disestablishment as the only effective way of achieving broad toleration. Rather than force a man's conscience, government should recognize the persuasive force of the gospel."

In the American colonies

Roger Williams

-People:* Roger Williams , Welsh soldier of fortune* Roger Williams , English theologian, co-founder of Rhode Island* Roger Williams , US actor...

and companions at the foundation of Rhode Island

Rhode Island

The state of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, more commonly referred to as Rhode Island , is a state in the New England region of the United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area...

entered into a compact binding themselves "to be obedient to the majority only in civil things". Lucian Johnston writes, "Williams' intention was to grant an infinitely greater religious liberty than then existed anywhere in the world outside of the Colony of Maryland". In 1663, Charles II granted the colony a charter guaranteeing complete religious toleration.

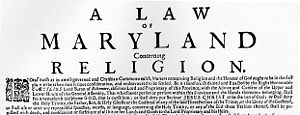

In 1649 Maryland passed the Maryland Toleration Act

Maryland Toleration Act

The Maryland Toleration Act, also known as the Act Concerning Religion, was a law mandating religious tolerance for trinitarian Christians. Passed on April 21, 1649 by the assembly of the Maryland colony, it was the second law requiring religious tolerance in the British North American colonies and...

, also known as the Act Concerning Religion, a law mandating religious tolerance for Trinitarian Christians only (excluding Nontrinitarian faiths). Passed on September 21, 1649 by the assembly of the Maryland colony, it was the first law requiring religious tolerance in the British North American colonies. The Calvert family sought enactment of the law to protect Catholic settlers and some of the other religions that did not conform to the dominant Anglicanism

Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a tradition within Christianity comprising churches with historical connections to the Church of England or similar beliefs, worship and church structures. The word Anglican originates in ecclesia anglicana, a medieval Latin phrase dating to at least 1246 that means the English...

of Britain and her colonies.

In 1657, New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam was a 17th-century Dutch colonial settlement that served as the capital of New Netherland. It later became New York City....

granted religious toleration to Jews.

Spinoza

Baruch SpinozaBaruch Spinoza

Baruch de Spinoza and later Benedict de Spinoza was a Dutch Jewish philosopher. Revealing considerable scientific aptitude, the breadth and importance of Spinoza's work was not fully realized until years after his death...

(1632–1677) was a Dutch Jewish philosopher. He published the Theological-Political Treatise anonymously in 1670, arguing (according to the Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) that "the freedom to philosophize can not only be granted without injury to piety and the peace of the Commonwealth, but that the peace of the Commonwealth and Piety are endangered by the suppression of this freedom", and defending, "as a political ideal, the tolerant, secular, and democratic polity". After analyzing certain Biblical texts, Spinoza opted for tolerance and freedom of thought in his conclusion that "every person is in duty bound to adapt these religious dogmas to his own understanding and to interpret them for himself in whatever way makes him feel that he can the more readily accept them with full confidence and conviction."

Locke

English philosopher John LockeJohn Locke

John Locke FRS , widely known as the Father of Liberalism, was an English philosopher and physician regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers. Considered one of the first of the British empiricists, following the tradition of Francis Bacon, he is equally important to social...

(1632–1704) published A Letter Concerning Toleration

A Letter Concerning Toleration

A Letter Concerning Toleration by John Locke was originally published in 1689. Its initial publication was in Latin, though it was immediately translated into other languages. Locke's work appeared amidst a fear that Catholicism might be taking over England, and responds to the problem of religion...

in 1689. Locke's work appeared amidst a fear that Catholicism might be taking over England, and responds to the problem of religion and government by proposing religious toleration as the answer.

Unlike Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury , in some older texts Thomas Hobbs of Malmsbury, was an English philosopher, best known today for his work on political philosophy...

, who saw uniformity of religion as the key to a well-functioning civil society, Locke argued that more religious groups actually prevent civil unrest. In his opinion, civil unrest results from confrontations caused by any magistrate's attempt to prevent different religions from being practiced, rather than tolerating their proliferation. However, Locke denies religious tolerance for Catholics, for political reasons, and also for atheists because 'Promises, covenants, and oaths, which are the bonds of human society, can have no hold upon an atheist'. A passage Locke later added to the Essay concerning Human Understanding, questioned whether atheism was necessarily inimical to political obedience.

Bayle

Pierre BaylePierre Bayle

Pierre Bayle was a French philosopher and writer best known for his seminal work the Historical and Critical Dictionary, published beginning in 1695....

(1647–1706) was a French Protestant scholar and philosopher who went into exile in Holland. In his "Dictionnaire historique and critique" and "Commentaire Philosophique" he advanced arguments for religious toleration (though, like some others of his time, he was not anxious to extend the same protection to Catholics he would to differing Protestant sects). Among his arguments were that every church believes it is the right one so "a heretical church would be in a position to persecute the true church". Bayle wrote that “the erroneous conscience procures for error the same rights and privileges that the orthodox conscience procures for truth.”

Bayle was repelled by the use of scripture to justify coercion and violence: "One must transcribe almost the whole New Testament to collect all the Proofs it affords us of that Gentleness and Long-suffering, which constitute the distinguishing and essential Character of the Gospel." He did not regard toleration as a danger to the state, but to the contrary: "If the Multiplicity of Religions prejudices the State, it proceeds from their not bearing with one another but on the contrary endeavoring each to crush and destroy the other by methods of Persecution. In a word, all the Mischief arises not from Toleration, but from the want of it."

Act of Toleration

The Act of TolerationAct of Toleration 1689

The Act of Toleration was an act of the English Parliament , the long title of which is "An Act for Exempting their Majestyes Protestant Subjects dissenting from the Church of England from the Penalties of certaine Lawes".The Act allowed freedom of worship to Nonconformists who had pledged to the...

, adopted by the British Parliament in 1689, allowed freedom of worship to Nonconformists who had pledged to the oaths of Allegiance and Supremacy and rejected transubstantiation The Nonconformists were Protestants who dissented from the Church of England such as Baptists and Congregationalists. They were allowed their own places of worship and their own teachers, if they accepted certain oaths of allegiance.

The Act did not apply to Catholics and non-trinitarians and continued the existing social and political disabilities for Dissenters, including their exclusion from political office and also from universities.

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet, the French writer, historian and philosopher known as VoltaireVoltaire

François-Marie Arouet , better known by the pen name Voltaire , was a French Enlightenment writer, historian and philosopher famous for his wit and for his advocacy of civil liberties, including freedom of religion, free trade and separation of church and state...

(1694–1778) published his "Treatise on Toleration" in 1763. In it he attacked religious views, but also said, "It does not require great art, or magnificently trained eloquence, to prove that Christians should tolerate each other. I, however, am going further: I say that we should regard all men as our brothers. What? The Turk my brother? The Chinaman my brother? The Jew? The Siam? Yes, without doubt; are we not all children of the same father and creatures of the same God?" On the other hand, Voltaire in his writings on religion was spiteful and intolerant of the practice of the Christian religion, and rabbi Joseph Telushkin

Joseph Telushkin

Joseph Telushkin is an American rabbi, lecturer, and author.-Biography:Telushkin attended the Yeshiva of Flatbush, was ordained at Yeshiva University, and studied Jewish history at Columbia University....

has claimed that the most significant of Enlightenment hostility against Judaism was found in Voltaire.

Lessing

Gotthold Ephraim LessingGotthold Ephraim Lessing

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing was a German writer, philosopher, dramatist, publicist, and art critic, and one of the most outstanding representatives of the Enlightenment era. His plays and theoretical writings substantially influenced the development of German literature...

(1729–1781), German dramatist and philosopher, trusted in a "Christianity of Reason", in which human reason (initiated by criticism and dissent) would develop, even without help by divine revelation. His plays about Jewish characters and themes, such as "Die Juden" and "Nathan der Weise", "have usually been considered impressive pleas for social and religious toleration". The latter work contains the famous parable of the three rings, in which three sons represent the three Abrahamic religions, Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. Each son believes he has the one true ring passed down by their father, but judgment on which is correct is reserved to God.

Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen (1789), adopted by the National Constituent AssemblyNational Constituent Assembly

The National Constituent Assembly was formed from the National Assembly on 9 July 1789, during the first stages of the French Revolution. It dissolved on 30 September 1791 and was succeeded by the Legislative Assembly.-Background:...

during the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

, states in Article 10: "No-one shall be interfered with for his opinions, even religious ones, provided that their practice doesn't disturb public order as established by the law." ("Nul ne doit être inquiété pour ses opinions, mêmes religieuses, pourvu que leur manifestation ne trouble pas l'ordre public établi par la loi.")

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution

The First Amendment to the United States ConstitutionFirst Amendment to the United States Constitution

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution is part of the Bill of Rights. The amendment prohibits the making of any law respecting an establishment of religion, impeding the free exercise of religion, abridging the freedom of speech, infringing on the freedom of the press, interfering...

, ratified along with the rest of the Bill of Rights

Bill of rights

A bill of rights is a list of the most important rights of the citizens of a country. The purpose of these bills is to protect those rights against infringement. The term "bill of rights" originates from England, where it referred to the Bill of Rights 1689. Bills of rights may be entrenched or...

on December 15, 1791, included the following words:"Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof..."

In 1802, Thomas Jefferson wrote a letter to the Danbury Baptists Association in which he said:

"...I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should 'make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,' thus building a wall of separation between Church & State."

In the nineteenth century

The process of legislating religious toleration went forward, while philosophers continued to discuss the underlying rationale.Catholic Relief Act

The Catholic Relief Act adopted by the Parliament in 1829 repealed the last of the criminal laws aimed at Catholic citizens of Great Britain.Mill

John Stuart MillJohn Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill was a British philosopher, economist and civil servant. An influential contributor to social theory, political theory, and political economy, his conception of liberty justified the freedom of the individual in opposition to unlimited state control. He was a proponent of...

's arguments in "On Liberty

On Liberty

On Liberty is a philosophical work by British philosopher John Stuart Mill. It was a radical work to the Victorian readers of the time because it supported individuals' moral and economic freedom from the state....

" (1859) in support of the freedom of speech were phrased to include a defense of religious toleration:

Let the opinions impugned be the belief of God and in a future state, or any of the commonly received doctrines of morality... But I must be permitted to observe that it is not the feeling sure of a doctrine (be it what it may) which I call an assumption of infallibility. It is the undertaking to decide that question for others, without allowing them to hear what can be said on the contrary side. And I denounce and reprobate this pretension not the less if it is put forth on the side of my most solemn convictions.

Renan

In his 1882 essay "What is a Nation?What is a Nation?

What is a Nation? is a 1882 essay by French historian Ernst Renan , known for the statements that a nation is "a daily referendum", and that nations are based as much on what the people jointly forget, as what they remember...

", French historian and philosopher Ernst Renan proposed a definition of nationhood based on "a spiritual principle" involving shared memories, rather than a common religious, racial or linguistic heritage. Thus members of any religious group could participate fully in the life of the nation. ""You can be French, English, German, yet Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, or practicing no religion".

In the twentieth century

In 1948, the United NationsUnited Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

General Assembly adopted Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a declaration adopted by the United Nations General Assembly . The Declaration arose directly from the experience of the Second World War and represents the first global expression of rights to which all human beings are inherently entitled...

, which states:

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance

Even though not formally legally binding, the Declaration has been adopted in or influenced many national constitutions since 1948. It also serves as the foundation for a growing number of international treaties and national laws and international, regional, national and sub-national institutions protecting and promoting human rights including the freedom of religion

Freedom of religion

Freedom of religion is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance; the concept is generally recognized also to include the freedom to change religion or not to follow any...

.

In 1965, The Roman Catholic Church Vatican II Council issued the decree Dignitatis Humanae

Dignitatis Humanae

Dignitatis Humanae is the Second Vatican Council's Declaration on Religious Freedom. In the context of the Council's stated intention “to develop the doctrine of recent popes on the inviolable rights of the human person and the constitutional order of society”, Dignitatis Humanae spells out the...

(Religious Freedom) that states that all people must have the right to religious freedom.

In 1986, the first World Day of Prayer for Peace

Day of Prayer

A Day of Prayer is a day allocated to prayer, either by leaders of religions or the general public, for a specific purpose. Such days are usually ecumenical in nature.-World Day of Prayer for Peace:...

was held in Assisi. Representatives of one hundred and twenty different religions came together for prayer to their God or gods.

In 1988, in the spirit of Glasnost

Glasnost

Glasnost was the policy of maximal publicity, openness, and transparency in the activities of all government institutions in the Soviet Union, together with freedom of information, introduced by Mikhail Gorbachev in the second half of the 1980s...

, Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev is a former Soviet statesman, having served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1985 until 1991, and as the last head of state of the USSR, having served from 1988 until its dissolution in 1991...

promised increased religious toleration.

In other religions

Other major world religions also have texts or practices supporting the idea of religious toleration.Islam

Circa 622, Muhammed established the Constitution of MedinaConstitution of Medina

The Constitution of Medina , also known as the Charter of Medina, was drafted by the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It constituted a formal agreement between Muhammad and all of the significant tribes and families of Yathrib , including Muslims, Jews, Christians and pagans. This constitution formed the...

, which incorporated religious freedom for Christians and Jews.

Certain verses of the Qu'ran were interpreted to create a specially tolerated status for People of the Book

People of the Book

People of the Book is a term used to designate non-Muslim adherents to faiths which have a revealed scripture called, in Arabic, Al-Kitab . The three types of adherents to faiths that the Qur'an mentions as people of the book are the Jews, Sabians and Christians.In Islam, the Muslim scripture, the...

, Jewish and Christian believers in the Old and New Testaments considered to have been a basis for Islamic religion:

Verily! Those who believe and those who are Jews and Christians, and Sabians, whoever believes in God and the Last Day and do righteous good deeds shall have their reward with their Lord, on them shall be no fear, nor shall they grieve .

Under Islamic law

Sharia

Sharia law, is the moral code and religious law of Islam. Sharia is derived from two primary sources of Islamic law: the precepts set forth in the Quran, and the example set by the Islamic prophet Muhammad in the Sunnah. Fiqh jurisprudence interprets and extends the application of sharia to...

, Jews and Christians were considered dhimmi

Dhimmi

A , is a non-Muslim subject of a state governed in accordance with sharia law. Linguistically, the word means "one whose responsibility has been taken". This has to be understood in the context of the definition of state in Islam...

s, a legal status inferior to that of a Muslim but superior to that of other non-Muslims.

Jewish communities in the Ottoman Empire held a protected status and continued to practice their own religion, as did Christians. Yitzhak Sarfati, born in Germany, became the Chief Rabbi of Edirne

Edirne

Edirne is a city in Eastern Thrace, the northwestern part of Turkey, close to the borders with Greece and Bulgaria. Edirne served as the capital city of the Ottoman Empire from 1365 to 1453, before Constantinople became the empire's new capital. At present, Edirne is the capital of the Edirne...

and wrote a letter inviting European Jews to settle in the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

, in which he asked:: "Is it not better for you to live under Muslims than under Christians?". Sultan Beyazid II (1481–1512), issued a formal invitation to the Jews expelled from Catholic Spain and Portugal, leading to a wave of Jewish immigration.

According to Michael Walzer:

The established religion of the [Ottoman] empire was Islam, but three other religious communities—Greek Orthodox, Armenian Orthodox, and Jewish—were permitted to form autonomous organizations. These three were equal among themselves, without regard to their relative numerical strength. They were subject to the same restrictions vis -a-vis Muslims—with regard to dress, proselytizing, and intermarriage, for example—and were allowed the same legal control over their own members.

Modern Islamic exegetics considers Qur'an as the source of religious tolerance http://salam.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/Tafsir.pdf

Hindu religion

The RigvedaRigveda

The Rigveda is an ancient Indian sacred collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns...

says Ekam Sath Viprah Bahudha Vadanti which translates to "The truth is One, but sages call it by different Names". Consistent with this tradition, India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

chose to be a secular country even though it was created after partitioning

Partition of India

The Partition of India was the partition of British India on the basis of religious demographics that led to the creation of the sovereign states of the Dominion of Pakistan and the Union of India on 14 and 15...

on religious lines. The Supreme Court of India has ruled that Sharia

Sharia

Sharia law, is the moral code and religious law of Islam. Sharia is derived from two primary sources of Islamic law: the precepts set forth in the Quran, and the example set by the Islamic prophet Muhammad in the Sunnah. Fiqh jurisprudence interprets and extends the application of sharia to...

or Muslim law, holds precedence for Muslims over Indian civil law.

Buddhism

Although the Buddha preached that "the path to the supreme goal of the holy life is made known only in his own teaching", according to Bhikkhu Boddhi, Buddhists have nevertheless shown significant tolerance for other religions: "Buddhist tolerance springs from the recognition that the dispositions and spiritual needs of human beings are too vastly diverse to be encompassed by any single teaching, and thus that these needs will naturally find expression in a wide variety of religious forms." James Freeman ClarkeJames Freeman Clarke

James Freeman Clarke , an American theologian and author.-Biography:Born in Hanover, New Hampshire, James Freeman Clarke attended the Boston Latin School, graduated from Harvard College in 1829, and Harvard Divinity School in 1833...

said in Ten Great Religions (1871): "The Buddhists have founded no Inquisition; they have combined the zeal which converted kingdoms with a toleration almost inexplicable to our Western experience."

The Edicts of Ashoka

Edicts of Ashoka

The Edicts of Ashoka are a collection of 33 inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka, as well as boulders and cave walls, made by the Emperor Ashoka of the Mauryan dynasty during his reign from 269 BCE to 231 BCE. These inscriptions are dispersed throughout the areas of modern-day Bangladesh, India,...

issued by King Ashoka the Great (269 – 231 BCE), a Buddhist, declared ethnic and religious tolerance. His Edict XII, engraved in stone, stated: "The faiths of others all deserve to be honored for one reason or another. By honoring them, one exalts one's own faith and at the same time performs a service to the faith of others."

Modern analyses and critiques of toleration

Contemporary commentators have highlighted situations in which toleration conflicts with widely held moral standards, national law, the principles of national identity, or other strongly held goals. Michael Walzer notes that the British in India tolerated the Hindu practice of suttee (ritual burning of a widow) until 1829. On the other hand, the United States declined to tolerate the MormonMormon

The term Mormon most commonly denotes an adherent, practitioner, follower, or constituent of Mormonism, which is the largest branch of the Latter Day Saint movement in restorationist Christianity...

practice of polygamy

Polygamy

Polygamy is a marriage which includes more than two partners...

. The French head scarf controversy

Islamic veil controversy in France

The Islamic scarf controversy in France, referred to there as l'affaire du voile , l'affaire du voile islamique , and l'affaire du foulard among other bynames, has arisen since the mid-1990s, especially pertaining to the wearing of the hijab in French public schools...

represents a conflict between religious practice and the French secular ideal. Toleration of the Romani

Romani

Romani relates or may refer to:- Nationality :*The Romani people**their Romani language*The Latin term for the ancient Romans, see Roman citizenship*The Italian term for inhabitants of Rome...

people in European countries is a continuing issue.

Modern definition

Historian Alexandra Walsham notes that the modern understanding of the word "toleration" may be very different from its historic meaning. Toleration in modern parlance has been analyzed as a component of a liberal or libertarianLibertarianism

Libertarianism, in the strictest sense, is the political philosophy that holds individual liberty as the basic moral principle of society. In the broadest sense, it is any political philosophy which approximates this view...

view of human rights

Human rights

Human rights are "commonly understood as inalienable fundamental rights to which a person is inherently entitled simply because she or he is a human being." Human rights are thus conceived as universal and egalitarian . These rights may exist as natural rights or as legal rights, in both national...

. Hans Oberdiek writes, "As long as no one is harmed or no one's fundamental rights are violated, the state should keep hands off, tolerating what those controlling the state find disgusting, deplorable or even debased. This for a long time has been the most prevalent defense of toleration by liberals...It is found, for example, in the writings of American philosophers John Rawls

John Rawls

John Bordley Rawls was an American philosopher and a leading figure in moral and political philosophy. He held the James Bryant Conant University Professorship at Harvard University....

, Robert Nozick

Robert Nozick

Robert Nozick was an American political philosopher, most prominent in the 1970s and 1980s. He was a professor at Harvard University. He is best known for his book Anarchy, State, and Utopia , a right-libertarian answer to John Rawls's A Theory of Justice...

, Ronald Dworkin

Ronald Dworkin

Ronald Myles Dworkin, QC, FBA is an American philosopher and scholar of constitutional law. He is Frank Henry Sommer Professor of Law and Philosophy at New York University and Emeritus Professor of Jurisprudence at University College London, and has taught previously at Yale Law School and the...

, Brian Barry

Brian Barry

Brian Barry FBA was a moral and political philosopher. He was educated at the Queen's College, Oxford, obtaining the degrees of B.A. and D.Phil under the direction of H. L. A. Hart....

, and a Canadian, Will Kymlicka

Will Kymlicka

Will Kymlicka is a Canadian political philosopher best known for his work on multiculturalism. He is currently Professor of Philosophy and Canada Research Chair in Political Philosophy at Queen's University at Kingston, and Recurrent Visiting Professor in the Nationalism Studies program at the...

, among others."

John Rawls

John Rawls

John Bordley Rawls was an American philosopher and a leading figure in moral and political philosophy. He held the James Bryant Conant University Professorship at Harvard University....

' "theory of 'political liberalism' conceives of toleration as a pragmatic response to the fact of diversity." Diverse groups learn to tolerate one another by developing "what Rawls calls 'overlapping consensus': individuals and groups with diverse metaphysical views or 'comprehensive schemes' will find reasons to agree about certain principles of justice that will include principles of toleration."

Herbert Marcuse

Herbert Marcuse

Herbert Marcuse was a German Jewish philosopher, sociologist and political theorist, associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory...

wrote "Repressive Tolerance

Repressive Tolerance

Repressive Tolerance is the title of a 1965 essay by Herbert Marcuse. In the essay, Marcuse, a Marxist and social theorist, argues that "pure tolerance" favors the political right and "the tyranny of the majority"....

" in 1965 where he argued that the "pure tolerance" that permits all favors totalitaliam democraty and tyranny of majority

Majority

A majority is a subset of a group consisting of more than half of its members. This can be compared to a plurality, which is a subset larger than any other subset; i.e. a plurality is not necessarily a majority as the largest subset may consist of less than half the group's population...

, and insisted the "repressive tolerance" against them.

Toleration of homosexuality

As a result of his public debate with Baron Devlin on the role of the criminal law in enforcing moral norms, British legal philosopher H.L.A. Hart wrote Law, Liberty and Morality (1963) and The Morality of the Criminal Law (1965). His work on the relationship between law and morality had a significant effect on the laws of Great Britain, helping bring about the decriminalization of homosexuality. But it was Jeremy BenthamJeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham was an English jurist, philosopher, and legal and social reformer. He became a leading theorist in Anglo-American philosophy of law, and a political radical whose ideas influenced the development of welfarism...

that defended the rights for homosexuality with his essay "Offence against One's Self" but could not be published until in 1978.

Tolerating the intolerant

Walzer asks "Should we tolerate the intolerant?" He notes that most minority religious groups who are the beneficiaries of tolerance are themselves intolerant, at least in some respects. In a tolerant regime, such people may learn to tolerate, or at least to behave "as if they possessed this virtue". Philosopher Karl PopperKarl Popper

Sir Karl Raimund Popper, CH FRS FBA was an Austro-British philosopher and a professor at the London School of Economics...

asserted, in The Open Society and Its Enemies

The Open Society and Its Enemies

The Open Society and Its Enemies is an influential two-volume work by Karl Popper written during World War II. Failing to find a publisher in the United States, it was first printed in London by Routledge in 1945...

Vol. 1, that we are warranted in refusing to tolerate intolerance. Philosopher John Rawls

John Rawls

John Bordley Rawls was an American philosopher and a leading figure in moral and political philosophy. He held the James Bryant Conant University Professorship at Harvard University....

concludes in A Theory of Justice

A Theory of Justice

A Theory of Justice is a book of political philosophy and ethics by John Rawls. It was originally published in 1971 and revised in both 1975 and 1999. In A Theory of Justice, Rawls attempts to solve the problem of distributive justice by utilising a variant of the familiar device of the social...

that a just society must tolerate the intolerant, for otherwise, the society would then itself be intolerant, and thus unjust. However, Rawls also insists, like Popper, that society has a reasonable right of self-preservation that supersedes the principle of tolerance: "While an intolerant sect does not itself have title to complain of intolerance, its freedom should be restricted only when the tolerant sincerely and with reason believe that their own security and that of the institutions of liberty are in danger."

Other criticisms and issues

Toleration has been described as undermining itself via moral relativismMoral relativism

Moral relativism may be any of several descriptive, meta-ethical, or normative positions. Each of them is concerned with the differences in moral judgments across different people and cultures:...

: "either the claim self-referentially undermines itself or it provides us with no compelling reason to believe it. If we are skeptical about knowledge, then we have no way of knowing that toleration is good."

Ronald Dworkin

Ronald Dworkin

Ronald Myles Dworkin, QC, FBA is an American philosopher and scholar of constitutional law. He is Frank Henry Sommer Professor of Law and Philosophy at New York University and Emeritus Professor of Jurisprudence at University College London, and has taught previously at Yale Law School and the...

argues that in exchange for toleration, minorities must bear with the criticisms and insults which are part of the freedom of speech in an otherwise tolerant society. Dworkin has also questioned whether the United States is a "tolerant secular" nation, or is re-characterizing itself as a "tolerant religious" nation, based on the increasing re-introduction of religious themes into conservative politics. Dworkin concludes that "the tolerant secular model is preferable, although he invited people to use the concept of personal responsibility to argue in favor of the tolerant religious model."

In The End of Faith

The End of Faith

The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason is a book written by Sam Harris, concerning organized religion, the clash between religious faith and rational thought, and the problems of tolerance towards religious fundamentalism....

, Sam Harris

Sam Harris (author)

Sam Harris is an American author, and neuroscientist, as well as the co-founder and current CEO of Project Reason. He received a Bachelor of Arts in philosophy from Stanford University, before receiving a Ph.D. in neuroscience from UCLA...

asserts that we should be unwilling to tolerate unjustified religious beliefs about morality, spirituality, politics, and the origin of humanity, especially beliefs which promote violence.

See also

- AnekantavadaAnekantavada' is one of the most important and fundamental doctrines of Jainism. It refers to the principles of pluralism and multiplicity of viewpoints, the notion that truth and reality are perceived differently from diverse points of view, and that no single point of view is the complete truth.Jains...

- Christian debate on persecution and toleration

- Conversational intolerance

- Islam and other religionsIslam and other religionsOver the centuries of Islamic history, Muslim rulers, Islamic scholars, and ordinary Muslims have held many different attitudes towards other religions...

- National churchNational churchNational church is a concept of a Christian church associated with a specific ethnic group or nation state. The idea was notably discussed during the 19th century, during the emergence of modern nationalism....

- Ontario Consultants on Religious ToleranceOntario Consultants on Religious ToleranceThe Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance are a small group in Kingston, Ontario dedicated to the promotion of religious tolerance through their website, ReligiousTolerance.org.-History of the group and its website:Bruce A...

- Religious discriminationReligious discriminationReligious discrimination is valuing or treating a person or group differently because of what they do or do not believe.A concept like that of 'religious discrimination' is necessary to take into account ambiguities of the term religious persecution. The infamous cases in which people have been...

- Religious intoleranceReligious intoleranceReligious intolerance is intolerance against another's religious beliefs or practices.-Definition:The mere statement on the part of a religion that its own beliefs and practices are correct and any contrary beliefs incorrect does not in itself constitute intolerance...

- Religious liberty

- Religious persecutionReligious persecutionReligious persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group of individuals as a response to their religious beliefs or affiliations or lack thereof....

- Religious pluralismReligious pluralismReligious pluralism is a loosely defined expression concerning acceptance of various religions, and is used in a number of related ways:* As the name of the worldview according to which one's religion is not the sole and exclusive source of truth, and thus that at least some truths and true values...

- Secular stateSecular stateA secular state is a concept of secularism, whereby a state or country purports to be officially neutral in matters of religion, supporting neither religion nor irreligion. A secular state also claims to treat all its citizens equally regardless of religion, and claims to avoid preferential...

- Separation of church and stateSeparation of church and stateThe concept of the separation of church and state refers to the distance in the relationship between organized religion and the nation state....

- State religionState religionA state religion is a religious body or creed officially endorsed by the state...

- Status of religious freedom by countryStatus of religious freedom by country-Afghanistan:The current government of Afghanistan has only been in place since 2002, following a U.S.-led invasion which displaced the former Taliban government...

External links

- Religion and Foreign Policy Initiative, Council on Foreign Relations, http://cfr.org/religion

- Background to the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- Text of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- Jehovah's witnesses: European Court of Human rights, Freedom of Religion, Speech, and Association in Europe

- History of Religious Tolerance

- The Foundation against Intolerance of Religious Minorities