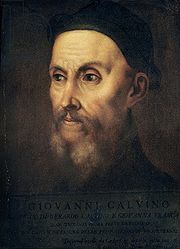

John Calvin

Encyclopedia

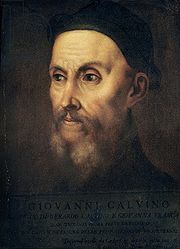

John Calvin was an influential French theologian

and pastor during the Protestant Reformation

. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of Christian theology

later called Calvinism

. Originally trained as a humanist

lawyer, he broke from the Roman Catholic Church around 1530. After religious tensions provoked a violent uprising against Protestants in France, Calvin fled to Basel

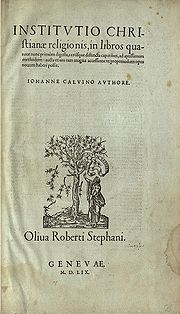

, Switzerland, where he published the first edition of his seminal work The Institutes of the Christian Religion in 1536.

In that year, Calvin was recruited by William Farel

to help reform the church in Geneva

. The city council resisted the implementation of Calvin and Farel's ideas, and both men were expelled. At the invitation of Martin Bucer

, Calvin proceeded to Strasbourg

, where he became the minister of a church of French refugees. He continued to support the reform movement in Geneva, and was eventually invited back to lead its church.

Following his return, Calvin introduced new forms of church government and liturgy

, despite the opposition of several powerful families in the city who tried to curb his authority. During this time, the trial of Michael Servetus

was extended by libertines in an attempt to harass Calvin. However, since Servetus was also condemned and wanted by the Inquisition

, outside pressure from all over Europe forced the trial to continue. Following an influx of supportive refugees and new elections to the city council, Calvin's opponents were forced out. Calvin spent his final years promoting the Reformation both in Geneva and throughout Europe.

Calvin was a tireless polemic

and apologetic

writer who generated much controversy. He also exchanged cordial and supportive letters with many reformers, including Philipp Melanchthon

and Heinrich Bullinger

. In addition to the Institutes, he wrote commentaries on most books of the Bible, as well as theological treatises and confessional documents

. He regularly preached sermons throughout the week in Geneva. Calvin was influenced by the Augustinian

tradition, which led him to expound the doctrine of predestination

and the absolute sovereignty

of God in salvation

of the human soul from death and eternal damnation

.

Calvin's writing and preachings provided the seeds for the branch of theology that bears his name. The Reformed

and Presbyterian churches, which look to Calvin as a chief expositor of their beliefs, have spread throughout the world.

Calvin was born as Jean Cauvin on 10 July 1509, in the town of Noyon

Calvin was born as Jean Cauvin on 10 July 1509, in the town of Noyon

in the Picardy region of France

. He was the first of four sons who survived infancy. His father, Gérard Cauvin

, had a prosperous career as the cathedral notary

and registrar to the ecclesiastical court

. He died in his later years, after suffering two years with testicular cancer. His mother, Jeanne le Franc, was the daughter of an innkeeper from Cambrai

. She died a few years after Calvin's birth from breast disease (not breast cancer). Gérard intended his three sons—Charles, Jean, and Antoine—for the priesthood.

Jean was particularly precocious; by age 12, he was employed by the bishop as a clerk and received the tonsure

, cutting his hair to symbolise his dedication to the Church. He also won the patronage of an influential family, the Montmors. Through their assistance, Calvin was able to attend the Collège de la Marche, in Paris, where he learned Latin

from one of its greatest teachers, Mathurin Cordier. Once he completed the course, he entered the Collège de Montaigu

as a philosophy student.

In 1525 or 1526, Gérard withdrew his son from the Collège de Montaigu and enrolled him in the University of Orléans

to study law. According to contemporary biographers Theodore Beza

and Nicolas Colladon

, Gérard believed his son would earn more money as a lawyer than as a priest. After a few years of quiet study, Calvin entered the University of Bourges

in 1529. He was intrigued by Andreas Alciati

, a humanist lawyer. Humanism was a European intellectual movement which stressed classical studies. During his 18-month stay in Bourges

, Calvin learned Greek

, a necessity for studying the New Testament

.

During the autumn of 1533 Calvin experienced a religious conversion

. In his later life, John Calvin wrote two different accounts of his conversion that differ in significant ways. In the first account he portrays his conversion as a sudden change of mind, brought about by God. This account can be found in his Commentary on the Book of Psalms:

In his second account he speaks of a long process of inner turmoil, followed by spiritual and psychological anguish.

Scholars have argued about the precise interpretation of these accounts, but it is agreed that his conversion corresponded with his break from the Roman Catholic Church. The Calvin biographer, Bruce Gordon, has stressed that "the two accounts are not antithetical, revealing some inconsistency in Calvin's memory, but rather [are] two different ways of expressing the same reality."

By 1532, Calvin received his licentiate

in law and published his first book, a commentary on Seneca

's De Clementia. After uneventful trips to Orléans and his hometown of Noyon, Calvin returned to Paris in October 1533. During this time, tensions rose at the Collège Royal (later to become the Collège de France) between the humanists/reformers and the conservative senior faculty members. One of the reformers, Nicolas Cop

, was rector of the university. On 1 November 1533 he devoted his inaugural address to the need for reform and renewal in the Catholic Church.

The address provoked a strong reaction from the faculty, who denounced it as heretical, forcing Cop to flee to Basel. Calvin, a close friend of Cop, was implicated in the offence, and for the next year he was forced into hiding. He remained on the move, sheltering with his friend Louis du Tillet in Angoulême

and taking refuge in Noyon and Orléans. He was finally forced to flee France during the Affair of the Placards

in mid-October 1534. In that incident, unknown reformers had posted placards in various cities attacking the Catholic mass

, which provoked a violent backlash against Protestants. In January 1535, Calvin joined Cop in Basel, a city under the influence of the reformer Johannes Oecolampadius

.

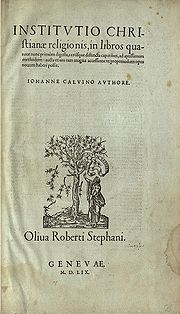

. The work was an apologia or defense of his faith and a statement of the doctrinal position of the reformers. He also intended it to serve as an elementary instruction book for anyone interested in the Christian religion. The book was the first expression of his theology

. Calvin updated the work and published new editions throughout his life. Shortly after its publication, he left Basel for Ferrara

, Italy, where he briefly served as secretary to Princess Renée of France

. By June he was back in Paris with his brother Antoine, who was resolving their father's affairs. Following the Edict of Coucy

, which gave a limited six-month period for heretics to reconcile with the Catholic faith, Calvin decided that there was no future for him in France. In August he set off for Strasbourg

, a free imperial city

of the Holy Roman Empire

and a refuge for reformers. Due to military manoeuvres of imperial and French forces, he was forced to make a detour to the south, bringing him to Geneva

.

Calvin had only intended to stay a single night, but William Farel

, a fellow French reformer residing in the city, implored a most reluctant Calvin to stay and assist him in work of reforming the church there – it was his duty before God, Farel insisted. Yet Calvin, for his part, desired only peace and privacy. But it was not to be; Farel's entreaties prevailed, but not before his having had recourse to the sternest imprecations. Calvin recalls the rather intense encounter:

Calvin accepted without any preconditions on his tasks or duties. The office to which he was initially assigned is unknown. He was eventually given the title of "reader", which most likely meant that he could give expository lectures on the Bible. Sometime in 1537 he was selected to be a "pastor", although he never received any pastoral consecration

. For the first time, the lawyer-theologian took up pastoral duties such as baptism

s, weddings, and church services.

Throughout the fall of 1536, Farel drafted a confession of faith while Calvin wrote separate articles on reorganising the church in Geneva. On 16 January 1537, Farel and Calvin presented their Articles concernant l'organisation de l'église et du culte à Genève (Articles on the Organisation of the Church and its Worship at Geneva) to the city council. The document described the manner and frequency of their celebrations of the eucharist

Throughout the fall of 1536, Farel drafted a confession of faith while Calvin wrote separate articles on reorganising the church in Geneva. On 16 January 1537, Farel and Calvin presented their Articles concernant l'organisation de l'église et du culte à Genève (Articles on the Organisation of the Church and its Worship at Geneva) to the city council. The document described the manner and frequency of their celebrations of the eucharist

, the reason for and the method of excommunication

, the requirement to subscribe to the confession of faith

, the use of congregational singing in the liturgy

, and the revision of marriage laws. The council accepted the document on the same day.

Throughout the year, however, Calvin and Farel's reputation with the council began to suffer. The council was reluctant to enforce the subscription requirement, as only a few citizens had subscribed to their confession of faith. On 26 November, the two ministers heatedly debated the council over the issue. Furthermore, France was taking an interest in forming an alliance with Geneva and as the two ministers were Frenchmen, councillors began to question their loyalty. Finally, a major ecclesiastical-political quarrel developed when Bern, Geneva’s ally in the reformation of the Swiss churches, proposed to introduce uniformity in the church ceremonies. One proposal required the use of unleavened bread for the eucharist

. The two ministers were unwilling to follow Bern's lead and delayed the use of such bread until a synod

in Zurich could be convened to make the final decision. The council ordered Calvin and Farel to use unleavened bread for the Easter eucharist; in protest, the ministers did not administer communion during the Easter service. This caused a riot during the service and the next day, the council told the ministers to leave Geneva.

Farel and Calvin went to Bern and Zurich to plead their case. The synod in Zurich placed most of the blame on Calvin for not being sympathetic enough toward the people of Geneva. However, it asked Bern to mediate with the aim of restoring the ministers. The Geneva council refused to readmit the two men, who took refuge in Basel. Subsequently Farel received an invitation to lead the church in Neuchâtel. Calvin was invited to lead a church of French refugees in Strasbourg by that city's leading reformers, Martin Bucer

and Wolfgang Capito. Initially Calvin refused because Farel was not included in the invitation, but relented when Bucer appealed to him. By September 1538 Calvin had taken up his new position in Strasbourg

, fully expecting that this time it would be permanent; a few months later, he applied for and was granted citizenship of the city.

and the former Dominican

Church, renamed the Temple Neuf. (All of these churches still exist, but none is in the architectural state of Calvin's days.) Calvin ministered to 400–500 members in his church. He preached or lectured every day, with two sermons on Sunday. Communion was celebrated monthly and congregational singing of the psalms was encouraged. He also worked on the second edition of the Institutes. Although the first edition sold out within a year, Calvin was dissatisfied with its structure as a catechism, a primer for young Christians.

For the second edition, published in 1539, Calvin dropped this format in favour of systematically presenting the main doctrines from scripture. In the process, the book was enlarged from six chapters to seventeen. He concurrently worked on another book, the Commentary on Romans, which was published in March 1540. The book was a model for his later commentaries: it included his own Latin translation from the Greek rather than the Latin Vulgate

, an exegesis

, and an exposition

. In the dedicatory letter, Calvin praised the work of his predecessors Philipp Melanchthon

, Heinrich Bullinger

, and Martin Bucer, but he also took care to distinguish his own work from theirs and to criticise some of their shortcomings.

Calvin's friends urged him to marry. Calvin took a prosaic view, writing to one correspondent:

Geneva reconsidered its expulsion of Calvin. Church attendance had dwindled and the political climate had changed; as Bern and Geneva quarrelled over land, their alliance frayed. When Cardinal Jacopo Sadoleto

wrote a letter to the city council inviting Geneva to return to the Catholic faith, the council searched for an ecclesiastical authority to respond to him. At first Pierre Viret

was consulted, but when he refused, the council asked Calvin. He agreed and his Responsio ad Sadoletum (Letter to Sadoleto) strongly defended Geneva's position concerning reforms in the church. On 21 September 1540 the council commissioned one of its members, Ami Perrin

, to find a way to recall Calvin. An embassy reached Calvin while he was at a colloquy

, a conference to settle religious disputes, in Worms

. His reaction to the suggestion was one of horror in which he wrote, "Rather would I submit to death a hundred times than to that cross on which I had to perish daily a thousand times over."

Calvin also wrote that he was prepared to follow the Lord's calling. A plan was drawn up in which Viret would be appointed to take temporary charge in Geneva for six months while Bucer and Calvin would visit the city to determine the next steps. However, the city council pressed for the immediate appointment of Calvin in Geneva. By summer 1541, Strasbourg decided to loan Calvin to Geneva for six months. Calvin returned on 13 September 1541 with an official escort and a wagon for his family.

In supporting Calvin's proposals for reforms, the council of Geneva passed the Ordonnances ecclésiastiques (Ecclesiastical Ordinances) on 20 November 1541. The ordinances defined four orders of ministerial function: pastors to preach and to administer the sacraments; doctors to instruct believers in the faith; elders

In supporting Calvin's proposals for reforms, the council of Geneva passed the Ordonnances ecclésiastiques (Ecclesiastical Ordinances) on 20 November 1541. The ordinances defined four orders of ministerial function: pastors to preach and to administer the sacraments; doctors to instruct believers in the faith; elders

to provide discipline; and deacons to care for the poor and needy. They also called for the creation of the Consistoire (Consistory

), an ecclesiastical court composed of the lay elders and the ministers. The city government retained the power to summon persons before the court, and the Consistory could judge only ecclesiastical matters having no civil jurisdiction. Originally, the court had the power to mete out sentences, with excommunication as its most severe penalty. However, the government contested this power and on 19 March 1543 the council decided that all sentencing would be carried out by the government.

In 1542, Calvin adapted a service book used in Strasbourg, publishing La Forme des Prières et Chants Ecclésiastiques (The Form of Prayers and Church Hymns). Calvin recognised the power of music and he intended that it be used to support scripture readings. The original Strasbourg psalter

contained twelve psalms by Clément Marot

and Calvin added several more hymns of his own composition in the Geneva version. At the end of 1542, Marot became a refugee in Geneva and contributed nineteen more psalms. Louis Bourgeois, also a refugee, lived and taught music in Geneva for sixteen years and Calvin took the opportunity to add his hymns, the most famous being the Old Hundredth.

In the same year of 1542, Calvin published Catéchisme de l'Eglise de Genève (Catechism of the Church of Geneva), which was inspired by Bucer's Kurze Schrifftliche Erklärung of 1534. Calvin had written an earlier catechism

during his first stay in Geneva which was largely based on Martin Luther

's Large Catechism. The first version was arranged pedagogically, describing Law, Faith, and Prayer. The 1542 version was rearranged for theological reasons, covering Faith first, then Law and Prayer.

During his ministry in Geneva, Calvin preached over two thousand sermons. Initially he preached twice on Sunday and three times during the week. This proved to be too heavy a burden and late in 1542 the council allowed him to preach only once on Sunday. However, in October 1549, he was again required to preach twice on Sundays and, in addition, every weekday of alternate weeks. His sermons lasted more than an hour and he did not use notes. An occasional secretary tried to record his sermons, but very little of his preaching was preserved before 1549. In that year, professional scribe Denis Raguenier, who had learned or developed a system of shorthand, was assigned to record all of Calvin's sermons. An analysis of his sermons by T.H.L. Parker suggests that Calvin was a consistent preacher and his style changed very little over the years.

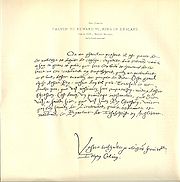

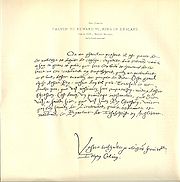

Very little is known about Calvin's personal life in Geneva. His house and furniture were owned by the council. The house was big enough to accommodate his family as well as Antoine's family and some servants. On 28 July 1542, Idelette gave birth to a son, Jacques, but he was born prematurely and survived only briefly. Idelette fell ill in 1545 and died on 29 March 1549. Calvin never married again. He expressed his sorrow in a letter to Viret:

Throughout the rest of his life in Geneva, he maintained several friendships from his early years including Montmor, Cordier, Cop, Farel, Melanchthon and Bullinger.

Calvin encountered bitter opposition to his work in Geneva. Around 1546, the uncoordinated forces coalesced into an identifiable group whom he referred to as the libertine

Calvin encountered bitter opposition to his work in Geneva. Around 1546, the uncoordinated forces coalesced into an identifiable group whom he referred to as the libertine

s. According to Calvin, these were people who felt that after being liberated through grace

, they were exempted from both ecclesiastical and civil law. The group consisted of wealthy, politically powerful, and interrelated families of Geneva. At the end of January 1546, Pierre Ameaux, a maker of playing cards who had already been in trouble with the Consistory, attacked Calvin by calling him a "Picard", an epithet denoting anti-French sentiment, and accused him of false doctrine. Ameaux was punished by the council and forced to make expiation by parading through the city and begging God for forgiveness. A few months later Ami Perrin, the man who had brought Calvin to Geneva, moved into open opposition. Perrin had married Françoise Favre, daughter of François Favre, a well-established Genevan merchant. Both Perrin's wife and father-in-law had previous quarrels with the Consistory. The court noted that many of Geneva's notables, including Perrin, had breached a law against dancing. Initially, Perrin ignored the court when he was summoned, but after receiving a letter from Calvin, he acquiesced and appeared quietly before the Consistory.

By 1547, opposition to Calvin and other French refugee ministers had grown to constitute the majority of the syndics, the civil magistrates of Geneva. On 27 June an unsigned threatening letter in Genevan dialect was found at the pulpit of St. Pierre Cathedral

where Calvin preached. Suspecting a plot against both the church and the state, the council appointed a commission to investigate. Jacques Gruet

, a Genevan member of Favre's group, was arrested and incriminating evidence was found when his house was searched. Under torture, he confessed to several crimes including writing the letter left in the pulpit which threatened God and his ambassadors and endeavouring to subvert church order. The civil court condemned him to death and, with Calvin's consent, he was beheaded on 26 July.

The libertines continued their opposition, taking opportunities to stir up discontent, to insult the ministers, and to defy the authority of the Consistory. The council straddled both sides of the conflict, alternately admonishing and upholding Calvin. When Perrin was elected first syndic in February 1552, Calvin's authority appeared to be at its lowest point. After some losses before the council, Calvin believed he was defeated; on 24 July 1553 he asked the council to allow him to resign. Although the libertines controlled the council, his request was refused. The opposition realised that they could curb Calvin's authority, but they did not have enough power to banish him.

The turning point in Calvin's fortunes occurred when Michael Servetus

The turning point in Calvin's fortunes occurred when Michael Servetus

, a fugitive from ecclesiastical authorities, appeared in Geneva on 13 August 1553. Servetus was a Spanish physician and Protestant theologian who boldly criticised the doctrine of the Trinity

and paedobaptism (infant baptism). In July 1530 he disputed with Johannes Oecolampadius

in Basel and was eventually expelled. He went to Strasbourg where he published a pamphlet against the Trinity. Bucer publicly refuted it and asked Servetus to leave. After returning to Basel, Servetus published Dialogorum de Trinitate libri duo (Two Books of Dialogues on the Trinity) which caused a sensation among Reformers and Catholics alike. The Inquisition in Spain

ordered his arrest.

Calvin and Servetus were first brought into contact in 1546 through a common acquaintance, Jean Frellon of Lyon.They exchanged letters debating doctrine signing as Michael Servetus and Charles d' Espeville,Calvin's pseudonym for these letters. Eventually, Calvin lost patience and refused to respond; by this time Servetus had written around thirty letters to Calvin. Calvin was particularly outraged when Servetus sent him a copy of the Institutes of the Christian Religion heavily annotated with arguments pointing to errors in the book. When Servetus mentioned that he would come to Geneva if Calvin agreed, Calvin wrote a letter to Farel on 13 February 1547 noting that if Servetus were to come, he would not assure him safe conduct: "for if he came, as far as my authority goes, I would not let him leave alive."

In 1553, Calvin's front man, Guillaume de Trie, sent letters trying to address the inquisition to Servetus. He was sending the letters and accusing Michael Servetus of being "castillian-portuguese", suspecting and accusing him of his recently proved jewish converso

origin. When the inquisitor-general of France learned that Servetus was hiding in Vienne

according to Calvin under an assumed name, he contacted Cardinal François de Tournon

, the secretary of the archbishop of Lyon, to take up the matter. Servetus was arrested and taken in for questioning. His letters to Calvin were presented as evidence of heresy, but he denied having written them, and later said he was not sure it was his handwriting. He said, after swearing before the holy gospel, that "he was Michel De Villeneuve Doctor in Medicine about 42 years old, native of Tudela

of the kingdom of Navarre

, a city under the obidience to the Emperor".The following day he said, after swearing before the holy gospel that " ..although he was not Servetus he assumed the person of Servet for debating with Calvin". He managed to escape from prison, and the Catholic authorities sentenced him in absentia to death by slow burning.

On his way to Italy, Servetus stopped in Geneva for unknown reasons and attended one of Calvin's sermons in St Pierre. Calvin had him arrested, and Calvin's secretary Nicholas de la Fontaine composed a list of accusations that was submitted before the court. The prosecutor was Philibert Berthelier

, a member of a libertine family and son of a famous Geneva patriot, and the sessions were led by Pierre Tissot, Perrin's brother-in-law. The libertines allowed the trial to drag on in an attempt to harass Calvin. The difficulty in using Servetus as a weapon against Calvin was that the heretical reputation of Servetus was widespread and most of the cities in Europe were observing and awaiting the outcome of the trial. This posed a dilemma for the libertines, so on 21 August the council decided to write to other Swiss churches for their opinions, thus mitigating their own responsibility for the final decision. While waiting for the responses, the council also asked Servetus if he preferred to be judged in Vienne or in Geneva. He begged to stay in Geneva. On 20 October the replies from Zurich, Basel, Bern, and Schaffhausen

were read and the council condemned Servetus as a heretic. The following day he was sentenced to burning at the stake, the same sentence as in Vienne. Calvin and other ministers asked that he be beheaded instead of burnt. This plea was refused and on 27 October, Servetus was burnt alive—atop a pyre of his own books—at the Plateau of Champel

at the edge of Geneva.

The libertines' downfall began with the February 1555 elections. By then, many of the French refugees had been granted citizenship and with their support, Calvin's partisans elected the majority of the syndics and the councillors. The libertines plotted to make trouble and on 16 May they set off to burn down a house that was supposedly full of Frenchmen. The syndic Henri Aulbert tried to intervene, carrying with him the baton of office

that symbolised his power. Perrin made the mistake of seizing the baton, thereby signifying that he was taking power, a virtual coup d'état. The insurrection was over as soon as it started when another syndic appeared and ordered Perrin to go with him to the town hall. Perrin and other leaders were forced to flee the city. With the approval of Calvin, the other plotters who remained in the city were found and executed. The opposition to Calvin's church polity came to an end.

Calvin's authority was practically uncontested during his final years, and he enjoyed an international reputation as a reformer distinct from Martin Luther

Calvin's authority was practically uncontested during his final years, and he enjoyed an international reputation as a reformer distinct from Martin Luther

. Initially, Luther and Calvin had mutual respect for each other. However, a doctrinal conflict had developed between Luther and Zurich reformer Huldrych Zwingli

on the interpretation of the eucharist

. Calvin's opinion on the issue forced Luther to place him in Zwingli's camp. Calvin actively participated in the polemics that were exchanged between the Lutheran and Reformed

branches of the Reformation movement. At the same time, Calvin was dismayed by the lack of unity among the reformers. He took steps toward rapprochement with Bullinger by signing the Consensus Tigurinus

, a concordat

between the Zurich and Geneva churches. He reached out to England when Archbishop of Canterbury

Thomas Cranmer

called for an ecumenical synod of all the evangelical churches. Calvin praised the idea, but ultimately Cranmer was unable to bring it to fruition.

Calvin's greatest contribution to the English-speaking community was his sheltering of Marian exiles

in Geneva starting in 1555. Under the city's protection, they were able to form their own reformed church under John Knox

and William Whittingham

and eventually carried Calvin's ideas on doctrine and polity back to England and Scotland. However, Calvin was most interested in reforming his homeland, France. He supported the building of churches by distributing literature and providing ministers. Between 1555 and 1562, more than 100 ministers were sent to France. These efforts were funded entirely by the church in Geneva, as the city council had refused to become involved in missionary activities at the time. Henry II

severely persecuted Protestants under the Edict of Chateaubriand and when the French authorities complained about the missionary activities, Geneva was able to disclaim responsibility.

Within Geneva, Calvin's main concern was the creation of a collège, an institute for the education of children. A site for the school was selected on 25 March 1558 and it opened the following year on 5 June 1559. Although the school was a single institution, it was divided into two parts: a grammar school called the collège or schola privata and an advanced school called the académie or schola publica. Calvin tried to recruit two professors for the institute, Mathurin Cordier, his old friend and Latin scholar who was now based in Lausanne

Within Geneva, Calvin's main concern was the creation of a collège, an institute for the education of children. A site for the school was selected on 25 March 1558 and it opened the following year on 5 June 1559. Although the school was a single institution, it was divided into two parts: a grammar school called the collège or schola privata and an advanced school called the académie or schola publica. Calvin tried to recruit two professors for the institute, Mathurin Cordier, his old friend and Latin scholar who was now based in Lausanne

, and Emmanuel Tremellius, the Regius professor of Hebrew

in Cambridge. Neither was available, but he succeeded in obtaining Theodore Beza

as rector. Within five years there were 1,200 students in the grammar school and 300 in the advanced school. The collège eventually became the Collège Calvin

, one of the college preparatory schools of Geneva, while the académie became the University of Geneva

.

In Autumn 1558, Calvin became ill with a fever. Since he was afraid that he might die before completing the final revision of the Institutes, he forced himself to work. The final edition was greatly expanded to the extent that Calvin referred to it as a new work. The expansion from 21 chapters of the previous edition to 80 was due to the extended treatment of existing material rather than the addition of new topics. Shortly after he recovered, he strained his voice while preaching, which brought on a violent fit of coughing. He burst a blood-vessel in his lungs, and his health steadily declined. He preached his final sermon in St. Pierre on 6 February 1564. On 25 April, he made his will, in which he left small sums to his family and to the collège. A few days later, the ministers of the church came to visit him, and he bade his final farewell, which was recorded in Discours d'adieu aux ministres. He recounted his life in Geneva, sometimes recalling bitterly some of the hardships he had suffered. Calvin died on 27 May 1564 aged 54. At first his body was laid in state, but since so many people came to see it, the reformers were afraid that they would be accused of fostering a new saint's cult. On the following day, he was buried in an unmarked grave in the Cimetière de Plainpalais

In Autumn 1558, Calvin became ill with a fever. Since he was afraid that he might die before completing the final revision of the Institutes, he forced himself to work. The final edition was greatly expanded to the extent that Calvin referred to it as a new work. The expansion from 21 chapters of the previous edition to 80 was due to the extended treatment of existing material rather than the addition of new topics. Shortly after he recovered, he strained his voice while preaching, which brought on a violent fit of coughing. He burst a blood-vessel in his lungs, and his health steadily declined. He preached his final sermon in St. Pierre on 6 February 1564. On 25 April, he made his will, in which he left small sums to his family and to the collège. A few days later, the ministers of the church came to visit him, and he bade his final farewell, which was recorded in Discours d'adieu aux ministres. He recounted his life in Geneva, sometimes recalling bitterly some of the hardships he had suffered. Calvin died on 27 May 1564 aged 54. At first his body was laid in state, but since so many people came to see it, the reformers were afraid that they would be accused of fostering a new saint's cult. On the following day, he was buried in an unmarked grave in the Cimetière de Plainpalais

. While the exact location of the grave is unknown, a stone was added in the 19th century to mark a grave traditionally thought to be Calvin's.

. He intended that the book be used as a summary of his views on Christian theology and that it be read in conjunction with his commentaries. The various editions of that work span nearly his entire career as a reformer, and the successive revisions of the book show that his theology changed very little from his youth to his death. The first edition from 1536 consisted of only six chapters. The second edition, published in 1539, was three times as long because he added chapters on subjects that appear in Melanchthon's Loci Communes

. In 1543, he again added new material and expanded a chapter on the Apostles' Creed

. The final edition of the Institutes appeared in 1559. By then, the work consisted of four books of eighty chapters, and each book was named after statements from the creed: Book 1 on God the Creator, Book 2 on the Redeemer in Christ, Book 3 on receiving the Grace of Christ through the Holy Spirit, and Book 4 on the Society of Christ or the Church.

The first statement in the Institutes acknowledges its central theme. It states that the sum of human wisdom consists of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves. Calvin argues that the knowledge of God is not inherent in humanity nor can it be discovered by observing this world. The only way to obtain it is to study scripture. Calvin writes, "For anyone to arrive at God the Creator he needs Scripture as his Guide and Teacher." He does not try to prove the authority of scripture but rather describes it as autopiston or self-authenticating. He defends the trinitarian view of God and, in a strong polemical stand against the Catholic Church, argues that images

The first statement in the Institutes acknowledges its central theme. It states that the sum of human wisdom consists of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves. Calvin argues that the knowledge of God is not inherent in humanity nor can it be discovered by observing this world. The only way to obtain it is to study scripture. Calvin writes, "For anyone to arrive at God the Creator he needs Scripture as his Guide and Teacher." He does not try to prove the authority of scripture but rather describes it as autopiston or self-authenticating. He defends the trinitarian view of God and, in a strong polemical stand against the Catholic Church, argues that images

of God lead to idolatry. At the end of the first book, he offers his views on providence

, writing, "By his Power God cherishes and guards the World which he made and by his Providence rules its individual Parts." Humans are unable to fully comprehend why God performs any particular action, but whatever good or evil people may practise, their efforts always result in the execution of God's will and judgments.

The second book includes several essays on the original sin

and the fall of man, which directly refer to Augustine

, who developed these doctrines. He often cited the Church Fathers

in order to defend the reformed cause against the charge that the reformers were creating new theology. In Calvin's view, sin began with the fall of Adam

and propagated to all of humanity. The domination of sin is complete to the point that people are driven to evil. Thus fallen humanity is in need of the redemption that can be found in Christ. But before Calvin expounded on this doctrine, he described the special situation of the Jews who lived during the time of the Old Testament

. God made a covenant with Abraham

and the substance of the promise was the coming of Christ. Hence, the Old Covenant

was not in opposition to Christ, but was rather a continuation of God's promise. Calvin then describes the New Covenant

using the passage from the Apostles' Creed

that describes Christ's suffering under Pontius Pilate

and his return to judge the living and the dead. For Calvin, the whole course of Christ's obedience to the Father removed the discord between humanity and God.

In the third book, Calvin describes how the spiritual union of Christ and humanity is achieved. He first defines faith as the firm and certain knowledge of God in Christ. The immediate effects of faith are repentance

and the remission of sin. This is followed by spiritual regeneration

, which returns the believer to the state of holiness before Adam's transgression. However, complete perfection is unattainable in this life, and the believer should expect a continual struggle against sin. Several chapters are then devoted to the subject of justification by faith alone

. He defined justification as "the acceptance by which God regards us as righteous whom he has received into grace." In this definition, it is clear that it is God who initiates and carries through the action and that people play no role; God is completely sovereign in salvation. Near the end of the book, Calvin describes and defends the doctrine of predestination

, a doctrine advanced by Augustine in opposition to the teachings of Pelagius

. Fellow theologians who followed the Augustinian tradition on this point included Thomas Aquinas

and Martin Luther. The principle, in Calvin's words, is that "God adopts some to the hope of life and adjudges others to eternal death."

The final book describes what he considers to be the true Church and its ministry, authority, and sacraments. He denied the papal claim to primacy

and the accusation that the reformers were schismatic

. For Calvin, the Church was defined as the body of believers who placed Christ at its head. By definition, there was only one "catholic" or "universal" Church. Hence, he argued that the reformers, "had to leave them in order that we might come to Christ." The ministers of the Church are described from a passage from Ephesians, and they consisted of apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastors, and doctors. Calvin regarded the first three offices as temporary, limited in their existence to the time of the New Testament. The latter two offices were established in the church in Geneva. Although Calvin respected the work of the ecumenical council

s, he considered them to be subject to God's Word, the teaching of scripture. He also believed that the civil and church authorities were separate and should not interfere with each other.

Calvin defined a sacrament as an earthly sign associated with a promise from God. He accepted only two sacraments as valid under the new covenant: baptism

and the Lord's Supper (in opposition to the Catholic acceptance of seven sacraments

). He completely rejected the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation

and the treatment of the Supper as a sacrifice. He also could not accept the Lutheran doctrine of sacramental union

in which Christ was "in, with and under" the elements. His own view was close to Zwingli's symbolic view, but it was not identical. Rather than holding a purely symbolic view, Calvin noted that with the participation of the Holy Spirit, faith was nourished and strengthened by the sacrament. In his words, the eucharistic rite was "a secret too sublime for my mind to understand or words to express. I experience it rather than understand it."

Calvin's theology was not without controversy. Pierre Caroli

Calvin's theology was not without controversy. Pierre Caroli

, a Protestant minister in Lausanne accused Calvin as well as Viret and Farel of Arianism

in 1536. Calvin defended his beliefs on the Trinity in Confessio de Trinitate propter calumnias P. Caroli. In 1551 Jérôme-Hermès Bolsec

, a physician in Geneva, attacked Calvin’s doctrine of predestination and accused him of making God the author of sin. Bolsec was banished from the city, and after Calvin’s death, he wrote a biography which severely maligned Calvin’s character. In the following year, Joachim Westphal

, a Gnesio-Lutheran pastor in Hamburg, condemned Calvin and Zwingli as heretics in denying the eucharistic doctrine of the union of Christ's body with the elements. Calvin's Defensio sanae et orthodoxae doctrinae de sacramentis (A Defence of the Sober and Orthodox Doctrine of the Sacrament) was his response in 1555. In 1556 Justus Velsius, a Dutch dissident, held a public disputation

with Calvin during his visit to Frankfurt

, in which Velsius defended free will

against Calvin's doctrine of predestination

. Following the execution of Servetus, a close associate of Calvin, Sebastian Castellio

, broke with him on the issue of the treatment of heretics. In Castellio's Treatise on Heretics (1554), he argued for a focus on Christ's moral teachings in place of the vanity of theology, and he afterward developed a theory of tolerance based on biblical principles.

Most of Calvin's statements on the Jewry of his era were polemical. For example, Calvin once wrote, "I have had much conversation with many Jews: I have never seen either a drop of piety or a grain of truth or ingenuousness – nay, I have never found common sense in any Jew." In this respect, he differed little from other Protestant and Catholic theologians of his day. He considered Jews deicides and “profane dogs,” model evildoers who "stupidly devour all the riches of the earth with their unrestrained cupidity."

Among his extant writings, Calvin only dealt explicitly with issues of contemporary Jews and Judaism in one treatise, Response to Questions and Objections of a Certain Jew. In it, he argued that Jews misread their own scriptures because they miss the unity of the Old and New Testaments. Calvin also wrote that the Jews' "rotten and unbending stiffneckedness deserves that they be oppressed unendingly and without measure or end and that they die in their misery without the pity of anyone."

's De Clementia. Published at his own expense in 1532, it showed that he was a humanist in the tradition of Erasmus with a thorough understanding of classical scholarship. His first theological work, the Psychopannychia, attempted to refute the doctrine of soul sleep as promulgated by the Anabaptists. Calvin probably wrote it during the period following Cop's speech, but it was not published until 1542 in Strasbourg.

Calvin produced commentaries on most of the books of the Bible. His first commentary on Romans

Calvin produced commentaries on most of the books of the Bible. His first commentary on Romans

was published in 1540, and he planned to write commentaries on the entire New Testament. Six years passed before he wrote his second, a commentary on I Corinthians, but after that he devoted more attention to reaching his goal. Within four years he had published commentaries on all the Pauline epistles

, and he also revised the commentary on Romans. He then turned his attention to the general epistles

, dedicating them to Edward VI of England

. By 1555 he had completed his work on the New Testament, finishing with the Acts

and the Gospels (he omitted only the brief second and third Epistles of John

and the Book of Revelation

). For the Old Testament, he wrote commentaries on Isaiah

, the books of the Pentateuch, the Psalms

, and Joshua

. The material for the commentaries often originated from lectures to students and ministers that he reworked for publication. However, from 1557 onwards, he could not find the time to continue this method, and he gave permission for his lectures to be published from stenographers' notes. These Praelectiones covered the minor prophets, Daniel

, Jeremiah

, Lamentations

, and part of Ezekiel

.

Calvin also wrote many letters and treatises. Following the Responsio ad Sadoletum, Calvin wrote an open letter at the request of Bucer to Charles V

in 1543, Supplex exhortatio ad Caesarem, defending the reformed faith. This was followed by an open letter to the pope (Admonitio paterna Pauli III) in 1544, in which Calvin admonished Paul III for depriving the reformers of any prospect of rapprochement. The pope proceeded to open the Council of Trent

, which resulted in decrees against the reformers. Calvin refuted the decrees by producing the Acta synodi Tridentinae cum Antidoto in 1547. When Charles tried to find a compromise solution with the Augsburg Interim

, Bucer and Bullinger urged Calvin to respond. He wrote the treatise, Vera Christianae pacificationis et Ecclesiae reformandae ratio in 1549, in which he described the doctrines that should be upheld, including justification by faith.

Calvin provided many of the foundational documents for reformed churches, including documents on the catechism, the liturgy, and church governance. He also produced several confessions of faith in order to unite the churches. In 1559, he drafted the French confession of faith, the Gallic Confession

, and the synod in Paris accepted it with few changes. The Belgic Confession

of 1561, a Dutch confession of faith, was partly based on the Gallic Confession.

After the deaths of Calvin and his successor, Beza, the Geneva city council gradually gained control over areas of life that were previously in the ecclesiastical domain. Increasing secularisation was accompanied by the decline of the church. Even the Geneva académie was eclipsed by universities in Leiden

After the deaths of Calvin and his successor, Beza, the Geneva city council gradually gained control over areas of life that were previously in the ecclesiastical domain. Increasing secularisation was accompanied by the decline of the church. Even the Geneva académie was eclipsed by universities in Leiden

and Heidelberg, which became the new strongholds of Calvin's ideas, first identified as "Calvinism

" by Joachim Westphal in 1552. By 1585, Geneva, once the wellspring of the reform movement, had become merely its symbol. However, Calvin had always warned against describing him as an "idol" and Geneva as a new "Jerusalem". He encouraged people to adapt to the environments in which they found themselves. Even during his polemical exchange with Westphal, he advised a group of French-speaking refugees, who had settled in Wesel

, Germany, to integrate with the local Lutheran churches. Despite his differences with the Lutherans, he did not deny that they were members of the true Church. Calvin’s recognition of the need to adapt to local conditions became an important characteristic of the reformation movement as it spread across Europe.

Due to Calvin's missionary work in France, his programme of reform eventually reached the French-speaking provinces of the Netherlands. Calvinism was adopted in the Palatinate under Frederick III

, which led to the formulation of the Heidelberg Catechism

in 1563. This and the Belgic Confession

were adopted as confessional standards in the first synod

of the Dutch Reformed Church

in 1571. Leading divines, either Calvinist or those sympathetic to Calvinism, settled in England (Martin Bucer, Peter Martyr

, and Jan Laski

) and Scotland (John Knox

). During the English Civil War

, the Calvinistic Puritan

s produced the Westminster Confession, which became the confessional standard for Presbyterians in the English-speaking world. Having established itself in Europe, the movement continued to spread to other parts of the world including North America, South Africa, and Korea.

Calvin did not live to see the foundation of his work grow into an international movement; but his death allowed his ideas to break out of their city of origin, to succeed far beyond their borders, and to establish their own distinct character.

, ISBN 0664220541 ISBN 9780664220549

Theology

Theology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

and pastor during the Protestant Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of Christian theology

Christian theology

- Divisions of Christian theology :There are many methods of categorizing different approaches to Christian theology. For a historical analysis, see the main article on the History of Christian theology.- Sub-disciplines :...

later called Calvinism

Calvinism

Calvinism is a Protestant theological system and an approach to the Christian life...

. Originally trained as a humanist

Renaissance humanism

Renaissance humanism was an activity of cultural and educational reform engaged by scholars, writers, and civic leaders who are today known as Renaissance humanists. It developed during the fourteenth and the beginning of the fifteenth centuries, and was a response to the challenge of Mediæval...

lawyer, he broke from the Roman Catholic Church around 1530. After religious tensions provoked a violent uprising against Protestants in France, Calvin fled to Basel

Basel

Basel or Basle In the national languages of Switzerland the city is also known as Bâle , Basilea and Basilea is Switzerland's third most populous city with about 166,000 inhabitants. Located where the Swiss, French and German borders meet, Basel also has suburbs in France and Germany...

, Switzerland, where he published the first edition of his seminal work The Institutes of the Christian Religion in 1536.

In that year, Calvin was recruited by William Farel

William Farel

William Farel , né Guilhem Farel, 1489 in Gap, Dauphiné, in south-eastern France, was a French evangelist, and a founder of the Reformed Church in the cantons of Neuchâtel, Berne, Geneva, and Vaud in Switzerland...

to help reform the church in Geneva

Geneva

Geneva In the national languages of Switzerland the city is known as Genf , Ginevra and Genevra is the second-most-populous city in Switzerland and is the most populous city of Romandie, the French-speaking part of Switzerland...

. The city council resisted the implementation of Calvin and Farel's ideas, and both men were expelled. At the invitation of Martin Bucer

Martin Bucer

Martin Bucer was a Protestant reformer based in Strasbourg who influenced Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anglican doctrines and practices. Bucer was originally a member of the Dominican Order, but after meeting and being influenced by Martin Luther in 1518 he arranged for his monastic vows to be annulled...

, Calvin proceeded to Strasbourg

Strasbourg

Strasbourg is the capital and principal city of the Alsace region in eastern France and is the official seat of the European Parliament. Located close to the border with Germany, it is the capital of the Bas-Rhin département. The city and the region of Alsace are historically German-speaking,...

, where he became the minister of a church of French refugees. He continued to support the reform movement in Geneva, and was eventually invited back to lead its church.

Following his return, Calvin introduced new forms of church government and liturgy

Christian liturgy

A liturgy is a set form of ceremony or pattern of worship. Christian liturgy is a pattern for worship used by a Christian congregation or denomination on a regular basis....

, despite the opposition of several powerful families in the city who tried to curb his authority. During this time, the trial of Michael Servetus

Michael Servetus

Michael Servetus was a Spanish theologian, physician, cartographer, and humanist. He was the first European to correctly describe the function of pulmonary circulation...

was extended by libertines in an attempt to harass Calvin. However, since Servetus was also condemned and wanted by the Inquisition

Inquisition

The Inquisition, Inquisitio Haereticae Pravitatis , was the "fight against heretics" by several institutions within the justice-system of the Roman Catholic Church. It started in the 12th century, with the introduction of torture in the persecution of heresy...

, outside pressure from all over Europe forced the trial to continue. Following an influx of supportive refugees and new elections to the city council, Calvin's opponents were forced out. Calvin spent his final years promoting the Reformation both in Geneva and throughout Europe.

Calvin was a tireless polemic

Polemic

A polemic is a variety of arguments or controversies made against one opinion, doctrine, or person. Other variations of argument are debate and discussion...

and apologetic

Christian apologetics

Christian apologetics is a field of Christian theology that aims to present a rational basis for the Christian faith, defend the faith against objections, and expose the perceived flaws of other world views...

writer who generated much controversy. He also exchanged cordial and supportive letters with many reformers, including Philipp Melanchthon

Philipp Melanchthon

Philipp Melanchthon , born Philipp Schwartzerdt, was a German reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lutheran Reformation, and an influential designer of educational systems...

and Heinrich Bullinger

Heinrich Bullinger

Heinrich Bullinger was a Swiss reformer, the successor of Huldrych Zwingli as head of the Zurich church and pastor at Grossmünster...

. In addition to the Institutes, he wrote commentaries on most books of the Bible, as well as theological treatises and confessional documents

Confession of Faith

A Confession of Faith is a statement of doctrine very similar to a creed, but usually longer and polemical, as well as didactic.Confessions of Faith are in the main, though not exclusively, associated with Protestantism...

. He regularly preached sermons throughout the week in Geneva. Calvin was influenced by the Augustinian

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo , also known as Augustine, St. Augustine, St. Austin, St. Augoustinos, Blessed Augustine, or St. Augustine the Blessed, was Bishop of Hippo Regius . He was a Latin-speaking philosopher and theologian who lived in the Roman Africa Province...

tradition, which led him to expound the doctrine of predestination

Predestination

Predestination, in theology is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God. John Calvin interpreted biblical predestination to mean that God willed eternal damnation for some people and salvation for others...

and the absolute sovereignty

Monergism

Monergism describes the position in Christian theology of those who believe that God, through the Holy Spirit, works to bring about effectually the salvation of individuals through spiritual regeneration without cooperation from the individual...

of God in salvation

Salvation

Within religion salvation is the phenomenon of being saved from the undesirable condition of bondage or suffering experienced by the psyche or soul that has arisen as a result of unskillful or immoral actions generically referred to as sins. Salvation may also be called "deliverance" or...

of the human soul from death and eternal damnation

Damnation

Damnation is the concept of everlasting divine punishment and/or disgrace, especially the punishment for sin as threatened by God . A damned being "in damnation" is said to be either in Hell, or living in a state wherein they are divorced from Heaven and/or in a state of disgrace from God's favor...

.

Calvin's writing and preachings provided the seeds for the branch of theology that bears his name. The Reformed

Reformed churches

The Reformed churches are a group of Protestant denominations characterized by Calvinist doctrines. They are descended from the Swiss Reformation inaugurated by Huldrych Zwingli but developed more coherently by Martin Bucer, Heinrich Bullinger and especially John Calvin...

and Presbyterian churches, which look to Calvin as a chief expositor of their beliefs, have spread throughout the world.

Early life (1509–1535)

Noyon

Noyon is a commune in the Oise department in northern France.It lies on the Oise Canal, 100 km north of Paris.-History:...

in the Picardy region of France

Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France was one of the most powerful states to exist in Europe during the second millennium.It originated from the Western portion of the Frankish empire, and consolidated significant power and influence over the next thousand years. Louis XIV, also known as the Sun King, developed a...

. He was the first of four sons who survived infancy. His father, Gérard Cauvin

Gérard Cauvin

Gérard Cauvin was the father of the Protestant Reformer John Calvin.Cauvin lived in Noyon, France located in the province of Picardy. Cauvin was a man of hard and severe character, occupied a prominent position as...

, had a prosperous career as the cathedral notary

Notary public

A notary public in the common law world is a public officer constituted by law to serve the public in non-contentious matters usually concerned with estates, deeds, powers-of-attorney, and foreign and international business...

and registrar to the ecclesiastical court

Ecclesiastical court

An ecclesiastical court is any of certain courts having jurisdiction mainly in spiritual or religious matters. In the Middle Ages in many areas of Europe these courts had much wider powers than before the development of nation states...

. He died in his later years, after suffering two years with testicular cancer. His mother, Jeanne le Franc, was the daughter of an innkeeper from Cambrai

Cambrai

Cambrai is a commune in the Nord department in northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department.Cambrai is the seat of an archdiocese whose jurisdiction was immense during the Middle Ages. The territory of the Bishopric of Cambrai, roughly coinciding with the shire of Brabant, included...

. She died a few years after Calvin's birth from breast disease (not breast cancer). Gérard intended his three sons—Charles, Jean, and Antoine—for the priesthood.

Jean was particularly precocious; by age 12, he was employed by the bishop as a clerk and received the tonsure

Tonsure

Tonsure is the traditional practice of Christian churches of cutting or shaving the hair from the scalp of clerics, monastics, and, in the Eastern Orthodox Church, all baptized members...

, cutting his hair to symbolise his dedication to the Church. He also won the patronage of an influential family, the Montmors. Through their assistance, Calvin was able to attend the Collège de la Marche, in Paris, where he learned Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

from one of its greatest teachers, Mathurin Cordier. Once he completed the course, he entered the Collège de Montaigu

Collège de Montaigu

The Collège de Montaigu was one of the constituent colleges of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Paris. The college, originally called the Collège des Aicelins, was founded in 1314 by Giles Aicelin, the Archbishop of Rouen...

as a philosophy student.

In 1525 or 1526, Gérard withdrew his son from the Collège de Montaigu and enrolled him in the University of Orléans

University of Orléans

-History:In 1230, when for a time the doctors of the University of Paris were scattered, a number of the teachers and disciples took refuge in Orléans; when pope Boniface VIII, in 1298, promulgated the sixth book of the Decretals, he appointed the doctors of Bologna and the doctors of Orléans to...

to study law. According to contemporary biographers Theodore Beza

Theodore Beza

Theodore Beza was a French Protestant Christian theologian and scholar who played an important role in the Reformation...

and Nicolas Colladon

Nicolas Colladon

Nicolas Colladon was a French Calvinist pastor.Calladon was the son of French parents who in 1536 took shelter in Switzerland for religious reasons. He studied theology at Lausanne and Geneva. He was a friend of John Calvin and pastor at Vandœuvres and Geneva...

, Gérard believed his son would earn more money as a lawyer than as a priest. After a few years of quiet study, Calvin entered the University of Bourges

University of Bourges

The University of Bourges was a university located in Bourges, France. It was founded by Louis XI in 1463 and deleted during french Revolution.-Notable alumni:* Patrick Adamson * John Calvin * Hugues Doneau...

in 1529. He was intrigued by Andreas Alciati

Andrea Alciato

Andrea Alciato , commonly known as Alciati , was an Italian jurist and writer. He is regarded as the founder of the French school of legal humanists.-Biography:...

, a humanist lawyer. Humanism was a European intellectual movement which stressed classical studies. During his 18-month stay in Bourges

Bourges

Bourges is a city in central France on the Yèvre river. It is the capital of the department of Cher and also was the capital of the former province of Berry.-History:...

, Calvin learned Greek

Greek language

Greek is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages. Native to the southern Balkans, it has the longest documented history of any Indo-European language, spanning 34 centuries of written records. Its writing system has been the Greek alphabet for the majority of its history;...

, a necessity for studying the New Testament

New Testament

The New Testament is the second major division of the Christian biblical canon, the first such division being the much longer Old Testament....

.

During the autumn of 1533 Calvin experienced a religious conversion

Religious conversion

Religious conversion is the adoption of a new religion that differs from the convert's previous religion. Changing from one denomination to another within the same religion is usually described as reaffiliation rather than conversion.People convert to a different religion for various reasons,...

. In his later life, John Calvin wrote two different accounts of his conversion that differ in significant ways. In the first account he portrays his conversion as a sudden change of mind, brought about by God. This account can be found in his Commentary on the Book of Psalms:

In his second account he speaks of a long process of inner turmoil, followed by spiritual and psychological anguish.

- Being exceedingly alarmed at the misery into which I had fallen, and much more at that which threatened me in view of eternal death, I, duty bound, made it my first business to betake myself to your way, condemning my past life, not without groans and tears. And now, O Lord, what remains to a wretch like me, but instead of defence, earnestly to supplicate you not to judge that fearful abandonment of your Word according to its deserts, from which in your wondrous goodness you have at last delivered me.

Scholars have argued about the precise interpretation of these accounts, but it is agreed that his conversion corresponded with his break from the Roman Catholic Church. The Calvin biographer, Bruce Gordon, has stressed that "the two accounts are not antithetical, revealing some inconsistency in Calvin's memory, but rather [are] two different ways of expressing the same reality."

By 1532, Calvin received his licentiate

Licentiate

Licentiate is the title of a person who holds an academic degree called a licence. The term may derive from the Latin licentia docendi, meaning permission to teach. The term may also derive from the Latin licentia ad practicandum, which signified someone who held a certificate of competence to...

in law and published his first book, a commentary on Seneca

Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca was a Roman Stoic philosopher, statesman, dramatist, and in one work humorist, of the Silver Age of Latin literature. He was tutor and later advisor to emperor Nero...

's De Clementia. After uneventful trips to Orléans and his hometown of Noyon, Calvin returned to Paris in October 1533. During this time, tensions rose at the Collège Royal (later to become the Collège de France) between the humanists/reformers and the conservative senior faculty members. One of the reformers, Nicolas Cop

Nicolas Cop

Nicolas Cop , rector of the University of Paris in late 1533, from 10 October 1533, was a Swiss Protestant Reformer and friend of Johannes Calvin...

, was rector of the university. On 1 November 1533 he devoted his inaugural address to the need for reform and renewal in the Catholic Church.

The address provoked a strong reaction from the faculty, who denounced it as heretical, forcing Cop to flee to Basel. Calvin, a close friend of Cop, was implicated in the offence, and for the next year he was forced into hiding. He remained on the move, sheltering with his friend Louis du Tillet in Angoulême

Angoulême

-Main sights:In place of its ancient fortifications, Angoulême is encircled by boulevards above the old city walls, known as the Remparts, from which fine views may be obtained in all directions. Within the town the streets are often narrow. Apart from the cathedral and the hôtel de ville, the...

and taking refuge in Noyon and Orléans. He was finally forced to flee France during the Affair of the Placards

Affair of the placards

The Affair of the Placards was an incident in which anti-Catholic posters appeared in public places in Paris and in four major provincial cities: Blois, Rouen, Tours and Orléans, overnight during 17 October 1534. One was actually posted on the bedchamber door of King Francis I at Amboise, an...

in mid-October 1534. In that incident, unknown reformers had posted placards in various cities attacking the Catholic mass

Mass (liturgy)

"Mass" is one of the names by which the sacrament of the Eucharist is called in the Roman Catholic Church: others are "Eucharist", the "Lord's Supper", the "Breaking of Bread", the "Eucharistic assembly ", the "memorial of the Lord's Passion and Resurrection", the "Holy Sacrifice", the "Holy and...

, which provoked a violent backlash against Protestants. In January 1535, Calvin joined Cop in Basel, a city under the influence of the reformer Johannes Oecolampadius

Johannes Oecolampadius

Johannes Œcolampadius was a German religious reformer. His real name was Hussgen or Heussgen .-Life:He was born in Weinsberg, then part of the Electoral Palatinate...

.

Reform work commences (1536–1538)

In March 1536, Calvin published the first edition of his Institutio Christianae Religionis or Institutes of the Christian ReligionInstitutes of the Christian Religion

The Institutes of the Christian Religion is John Calvin's seminal work on Protestant systematic theology...

. The work was an apologia or defense of his faith and a statement of the doctrinal position of the reformers. He also intended it to serve as an elementary instruction book for anyone interested in the Christian religion. The book was the first expression of his theology

Calvinism

Calvinism is a Protestant theological system and an approach to the Christian life...

. Calvin updated the work and published new editions throughout his life. Shortly after its publication, he left Basel for Ferrara

Ferrara

Ferrara is a city and comune in Emilia-Romagna, northern Italy, capital city of the Province of Ferrara. It is situated 50 km north-northeast of Bologna, on the Po di Volano, a branch channel of the main stream of the Po River, located 5 km north...

, Italy, where he briefly served as secretary to Princess Renée of France

Renée of France

Renée de France was the younger daughter of Louis XII of France and Anne, Duchess of Brittany. Her elder sister was Queen Claude of France. She was the Duchess of Ferrara due to her marriage to Ercole II d'Este, grandson of Pope Alexander VI...

. By June he was back in Paris with his brother Antoine, who was resolving their father's affairs. Following the Edict of Coucy

Edict of Coucy

King Francis I of France issued the Edict of Coucy on July 16, 1535, ending the persecution of Protestants that followed Nicolas Cop's speech on November 1, 1533 calling for reform in the Catholic Church, and the provocative placards that were posted almost a year later in Paris and elsewhere,...

, which gave a limited six-month period for heretics to reconcile with the Catholic faith, Calvin decided that there was no future for him in France. In August he set off for Strasbourg

Strasbourg

Strasbourg is the capital and principal city of the Alsace region in eastern France and is the official seat of the European Parliament. Located close to the border with Germany, it is the capital of the Bas-Rhin département. The city and the region of Alsace are historically German-speaking,...

, a free imperial city

Free Imperial City

In the Holy Roman Empire, a free imperial city was a city formally ruled by the emperor only — as opposed to the majority of cities in the Empire, which were governed by one of the many princes of the Empire, such as dukes or prince-bishops...

of the Holy Roman Empire

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

and a refuge for reformers. Due to military manoeuvres of imperial and French forces, he was forced to make a detour to the south, bringing him to Geneva

Geneva

Geneva In the national languages of Switzerland the city is known as Genf , Ginevra and Genevra is the second-most-populous city in Switzerland and is the most populous city of Romandie, the French-speaking part of Switzerland...

.

Calvin had only intended to stay a single night, but William Farel

William Farel

William Farel , né Guilhem Farel, 1489 in Gap, Dauphiné, in south-eastern France, was a French evangelist, and a founder of the Reformed Church in the cantons of Neuchâtel, Berne, Geneva, and Vaud in Switzerland...

, a fellow French reformer residing in the city, implored a most reluctant Calvin to stay and assist him in work of reforming the church there – it was his duty before God, Farel insisted. Yet Calvin, for his part, desired only peace and privacy. But it was not to be; Farel's entreaties prevailed, but not before his having had recourse to the sternest imprecations. Calvin recalls the rather intense encounter:

Then Farel, who was working with incredible zeal to promote the gospel, bent all his efforts to keep me in the city. And when he realized that I was determined to study in privacy in some obscure place, and saw that he gained nothing by entreaty, he descended to cursing, and said that God would surely curse my peace if I held back from giving help at a time of such great need. Terrified by his words, and conscience of my own timidity and cowardice, I gave up my journey and attempted to apply whatever gift I had in defense of my faith.

Calvin accepted without any preconditions on his tasks or duties. The office to which he was initially assigned is unknown. He was eventually given the title of "reader", which most likely meant that he could give expository lectures on the Bible. Sometime in 1537 he was selected to be a "pastor", although he never received any pastoral consecration

Ordination

In general religious use, ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart as clergy to perform various religious rites and ceremonies. The process and ceremonies of ordination itself varies by religion and denomination. One who is in preparation for, or who is...

. For the first time, the lawyer-theologian took up pastoral duties such as baptism

Baptism

In Christianity, baptism is for the majority the rite of admission , almost invariably with the use of water, into the Christian Church generally and also membership of a particular church tradition...

s, weddings, and church services.

Eucharist

The Eucharist , also called Holy Communion, the Sacrament of the Altar, the Blessed Sacrament, the Lord's Supper, and other names, is a Christian sacrament or ordinance...

, the reason for and the method of excommunication

Excommunication

Excommunication is a religious censure used to deprive, suspend or limit membership in a religious community. The word means putting [someone] out of communion. In some religions, excommunication includes spiritual condemnation of the member or group...

, the requirement to subscribe to the confession of faith

Confession of Faith

A Confession of Faith is a statement of doctrine very similar to a creed, but usually longer and polemical, as well as didactic.Confessions of Faith are in the main, though not exclusively, associated with Protestantism...

, the use of congregational singing in the liturgy

Christian liturgy

A liturgy is a set form of ceremony or pattern of worship. Christian liturgy is a pattern for worship used by a Christian congregation or denomination on a regular basis....

, and the revision of marriage laws. The council accepted the document on the same day.

Throughout the year, however, Calvin and Farel's reputation with the council began to suffer. The council was reluctant to enforce the subscription requirement, as only a few citizens had subscribed to their confession of faith. On 26 November, the two ministers heatedly debated the council over the issue. Furthermore, France was taking an interest in forming an alliance with Geneva and as the two ministers were Frenchmen, councillors began to question their loyalty. Finally, a major ecclesiastical-political quarrel developed when Bern, Geneva’s ally in the reformation of the Swiss churches, proposed to introduce uniformity in the church ceremonies. One proposal required the use of unleavened bread for the eucharist

Eucharist

The Eucharist , also called Holy Communion, the Sacrament of the Altar, the Blessed Sacrament, the Lord's Supper, and other names, is a Christian sacrament or ordinance...

. The two ministers were unwilling to follow Bern's lead and delayed the use of such bread until a synod

Synod

A synod historically is a council of a church, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. In modern usage, the word often refers to the governing body of a particular church, whether its members are meeting or not...

in Zurich could be convened to make the final decision. The council ordered Calvin and Farel to use unleavened bread for the Easter eucharist; in protest, the ministers did not administer communion during the Easter service. This caused a riot during the service and the next day, the council told the ministers to leave Geneva.

Farel and Calvin went to Bern and Zurich to plead their case. The synod in Zurich placed most of the blame on Calvin for not being sympathetic enough toward the people of Geneva. However, it asked Bern to mediate with the aim of restoring the ministers. The Geneva council refused to readmit the two men, who took refuge in Basel. Subsequently Farel received an invitation to lead the church in Neuchâtel. Calvin was invited to lead a church of French refugees in Strasbourg by that city's leading reformers, Martin Bucer

Martin Bucer

Martin Bucer was a Protestant reformer based in Strasbourg who influenced Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anglican doctrines and practices. Bucer was originally a member of the Dominican Order, but after meeting and being influenced by Martin Luther in 1518 he arranged for his monastic vows to be annulled...

and Wolfgang Capito. Initially Calvin refused because Farel was not included in the invitation, but relented when Bucer appealed to him. By September 1538 Calvin had taken up his new position in Strasbourg

Strasbourg

Strasbourg is the capital and principal city of the Alsace region in eastern France and is the official seat of the European Parliament. Located close to the border with Germany, it is the capital of the Bas-Rhin département. The city and the region of Alsace are historically German-speaking,...

, fully expecting that this time it would be permanent; a few months later, he applied for and was granted citizenship of the city.

Minister in Strasbourg (1538–1541)

During his time in Strasbourg, Calvin was not attached to one particular church, but held his office successively in the Saint-Nicolas Church, the Sainte-Madeleine ChurchSainte-Madeleine Church, Strasbourg