Smallpox

Encyclopedia

Smallpox was an infectious disease

unique to humans, caused by either of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor. The disease is also known by the Latin

names Variola or Variola vera, which is a derivative of the Latin varius, meaning "spotted", or varus, meaning "pimple". The term "smallpox" was first used in Europe in the 15th century to distinguish variola from the "great pox" (syphilis

).

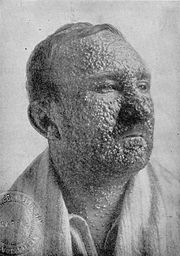

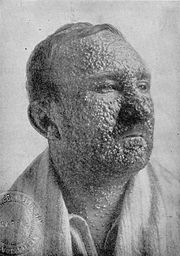

Smallpox localizes in small blood vessel

s of the skin and in the mouth and throat. In the skin, this results in a characteristic maculopapular rash, and later, raised fluid-filled blister

s. V. major produces a more serious disease and has an overall mortality rate

of 30–35%. V. minor causes a milder form of disease (also known as alastrim

, cottonpox, milkpox, whitepox, and Cuban itch) which kills about 1% of its victims. Long-term complications of V. major infection include characteristic scars, commonly on the face, which occur in 65–85% of survivors. Blindness

resulting from corneal ulcer

ation and scarring, and limb deformities due to arthritis and osteomyelitis

are less common complications, seen in about 2–5% of cases.

Smallpox is believed to have emerged in human populations about 10,000 BC. The earliest physical evidence of smallpox is probably the pustular rash on the mummified body of Pharaoh Ramses V of Egypt. The disease killed an estimated 400,000 Europeans per year during the closing years of the 18th century (including five reigning monarch

s), and was responsible for a third of all blindness. Of all those infected, 20–60%—and over 80% of infected children—died from the disease. Smallpox was responsible for an estimated 300–500 million deaths during the 20th century. As recently as 1967, the World Health Organization

(WHO) estimated that 15 million people contracted the disease and that two million died in that year.

After vaccination

campaigns throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the WHO certified the eradication of smallpox in 1979. Smallpox is one of the two infectious disease

s to have been eradicated, the other being rinderpest

, which was declared eradicated in 2011.

is a less common presentation, and a much less severe disease, with historical death rates of 1% or less. Subclinical (asymptomatic

) infections with variola virus have been noted, but are not common. In addition, a form called variola sine eruptione (smallpox without rash) is seen generally in vaccinated persons. This form is marked by a fever that occurs after the usual incubation period and can be confirmed only by antibody studies or, rarely, by virus isolation.

The incubation period

The incubation period

between contraction and the first obvious symptoms of the disease is around 12 days. Once inhaled, variola major virus invades the oropharyngeal (mouth and throat) or the respiratory mucosa, migrates to regional lymph nodes, and begins to multiply. In the initial growth phase the virus seems to move from cell to cell, but around the 12th day, lysis

of many infected cells occurs and the virus is found in the blood

stream in large numbers (this is called viremia

), and a second wave of multiplication occurs in the spleen, bone marrow

, and lymph nodes. The initial or prodromal symptoms are similar to other viral diseases such as influenza

and the common cold

: fever

of at least 38.5 °C (101 °F), muscle pain

, malaise, headache and prostration

. As the digestive tract

is commonly involved, nausea and vomiting and backache often occur. The prodrome, or preeruptive stage, usually lasts 2–4 days. By days 12–15 the first visible lesions—small reddish spots called enanthem

—appear on mucous membranes of the mouth, tongue, palate

, and throat, and temperature falls to near normal. These lesions rapidly enlarge and rupture, releasing large amounts of virus into the saliva

.

Smallpox virus preferentially attacks skin cells, causing the characteristic pimples (called macules) associated with the disease. A rash develops on the skin 24 to 48 hours after lesions on the mucous membranes appear. Typically the macules first appear on the forehead, then rapidly spread to the whole face, proximal portions of extremities, the trunk, and lastly to distal portions of extremities. The process takes no more than 24 to 36 hours, after which no new lesions appear. At this point variola major infection can take several very different courses, resulting in four types of smallpox disease based on the Rao classification: ordinary, modified, malignant (or flat), and hemorrhagic. Historically, smallpox has an overall fatality rate of about 30%; however, the malignant and hemorrhagic forms are usually fatal.

s. By the third or fourth day the papules fill with an opalescent fluid to become vesicles. This fluid becomes opaque

and turbid within 24–48 hours, giving them the appearance of pustules; however, the so-called pustules are filled with tissue debris, not pus.

By the sixth or seventh day, all the skin lesions have become pustules. Between 7 and 10 days the pustules mature and reach their maximum size. The pustules are sharply raised, typically round, tense, and firm to the touch. The pustules are deeply embedded in the dermis, giving them the feel of a small bead in the skin. Fluid slowly leaks from the pustules, and by the end of the second week the pustules deflate, and start to dry up, forming crusts (or scabs). By day 16–20 scabs have formed over all the lesions, which have started to flake off, leaving depigmented

scars.

Ordinary smallpox generally produces a discrete rash, in which the pustules stand out on the skin separately. The distribution of the rash is densest on the face; denser on the extremities than on the trunk; and on the extremities, denser on the distal parts than on the proximal. The palms of the hands and soles of the feet are involved in the majority of cases. Sometimes, the blisters merge together into sheets, forming a confluent rash, which begin to detach the outer layers of skin from the underlying flesh. Patients with confluent smallpox often remain ill even after scabs have formed over all the lesions. In one case series, the case-fatality rate in confluent smallpox was 62%.

.

. The rash on the tongue and palate is extensive. Skin lesions mature slowly and by the seventh or eighth day they are flat and appear to be buried in the skin. Unlike ordinary-type smallpox, the vesicles contain little fluid, are soft and velvety to the touch, and may contain hemorrhages. Malignant smallpox is nearly always fatal.

.

In the early, or fulminating form, hemorrhaging appears on the second or third day as sub-conjunctival bleeding turns the whites of the eyes deep red. Hemorrhagic smallpox also produces a dusky erythema

, petechiae, and hemorrhages in the spleen, kidney, serosa, muscle, and, rarely, the epicardium

, liver

, testes, ovaries and bladder

. Death often occurs suddenly between the fifth and seventh days of illness, when only a few insignificant skin lesions are present. A later form of the disease occurs in patients who survive for 8–10 days. The hemorrhages appear in the early eruptive period, and the rash is flat and does not progress beyond the vesicular stage. Patients in the early stage of disease show a decrease in coagulation factors (e.g. platelet

s, prothrombin, and globulin

) and an increase in circulating antithrombin

. Patients in the late stage have significant thrombocytopenia

; however, deficiency of coagulation factors is less severe. Some in the late stage also show increased antithrombin. This form of smallpox occurs in anywhere from 3 to 25% of fatal cases depending on the virulence of the smallpox strain. Hemorrhagic smallpox is usually fatal.

, the family Poxviridae

and subfamily chordopoxvirinae. Variola is a large brick-shaped virus measuring approximately 302 to 350 nanometers by 244 to 270 nm, with a single linear double stranded DNA genome

186 kilobase pairs (kbp) in size and containing a hairpin loop at each end. The two classic varieties of smallpox are variola major and variola minor.

Four orthopoxviruses cause infection in humans: variola, vaccinia

, cowpox

, and monkeypox

. Variola virus infects only humans in nature, although primates and other animals have been infected in a laboratory setting. Vaccinia, cowpox, and monkeypox viruses can infect both humans and other animals in nature.

The lifecycle of poxviruses is complicated by having multiple infectious forms, with differing mechanisms of cell entry. Poxviruses are unique among DNA viruses in that they replicate in the cytoplasm

of the cell rather than in the nucleus

. In order to replicate, poxviruses produce a variety of specialized proteins not produced by other DNA viruses, the most important of which is a viral-associated DNA-dependent RNA polymerase.

Both enveloped

and unenveloped virions are infectious. The viral envelope is made of modified Golgi

membranes containing viral-specific polypeptides, including hemagglutinin

. Infection with either variola major or variola minor confers immunity against the other.

variola virus, usually droplets expressed from the oral, nasal, or pharyngeal

mucosa of an infected person. It is transmitted from one person to another primarily through prolonged face-to-face contact with an infected person, usually within a distance of 6 feet (1.8 m), but can also be spread through direct contact with infected bodily fluid

s or contaminated objects (fomite

s) such as bedding or clothing. Rarely, smallpox has been spread by virus carried in the air in enclosed settings such as buildings, buses, and trains. The virus can cross the placenta

, but the incidence of congenital smallpox is relatively low.

Smallpox is not notably infectious in the prodromal

period and viral shedding is usually delayed until the appearance of the rash, which is often accompanied by lesion

s in the mouth and pharynx. The virus can be transmitted throughout the course of the illness, but is most frequent during the first week of the rash, when most of the skin lesions are intact. Infectivity wanes in 7 to 10 days when scabs form over the lesions, but the infected person is contagious until the last smallpox scab falls off.

Smallpox is highly contagious, but generally spreads more slowly and less widely than some other viral diseases, perhaps because transmission requires close contact and occurs after the onset of the rash. The overall rate of infection is also affected by the short duration of the infectious stage. In temperate

areas, the number of smallpox infections were highest during the winter and spring. In tropical areas, seasonal variation was less evident and the disease was present throughout the year. Age distribution of smallpox infections depends on acquired immunity. Vaccination

immunity

declines over time and is probably lost in all but the most recently vaccinated populations. Smallpox is not known to be transmitted by insects or animals and there is no asymptomatic carrier

state.

Microscopically

, poxviruses produce characteristic cytoplasmic inclusions, the most important of which are known as Guarnieri bodies

, and are the sites of viral replication

. Guarnieri bodies are readily identified in skin biopsies stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and appear as pink blobs. They are found in virtually all poxvirus infections but the absence of Guarnieri bodies cannot be used to rule out smallpox. The diagnosis of an orthopoxvirus infection can also be made rapidly by electron microscopic examination of pustular fluid or scabs. However, all orthopoxviruses exhibit identical brick-shaped virions by electron microscopy.

Definitive laboratory identification of variola virus involves growing the virus on chorioallantoic membrane

(part of a chicken embryo

) and examining the resulting pock lesions under defined temperature conditions. Strains may be characterized by polymerase chain reaction

(PCR) and restriction fragment length polymorphism

(RFLP) analysis. Serologic tests and enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), which measure variola virus-specific immunoglobulin and antigen have also been developed to assist in the diagnosis of infection.

Chickenpox

was commonly confused with smallpox in the immediate post-eradication era. Chickenpox and smallpox can be distinguished by several methods. Unlike smallpox, chickenpox does not usually affect the palms and soles. Additionally, chickenpox pustules are of varying size due to variations in the timing of pustule eruption: smallpox pustules are all very nearly the same size since the viral effect progresses more uniformly. A variety of laboratory methods are available for detecting chickenpox in evaluation of suspected smallpox cases.

The earliest procedure used to prevent smallpox was inoculation

The earliest procedure used to prevent smallpox was inoculation

(also known as variolation). Inoculation was possibly practiced in India as early as 1000 BC, and involved either nasal insufflation of powdered smallpox scabs, or scratching material from a smallpox lesion into the skin. However, the idea that inoculation originated in India has been challenged as few of the ancient Sanskrit

medical texts described the process of inoculation. Accounts of inoculation against smallpox in China can be found as early as the late 10th century, and the procedure was widely practiced by the 16th century, during the Ming Dynasty

. If successful, inoculation produced lasting immunity

to smallpox. However, because the person was infected with variola virus, a severe infection could result, and the person could transmit smallpox to others. Variolation had a 0.5–2% mortality rate, considerably less than the 20–30% mortality rate of the disease itself.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

observed smallpox inoculation during her stay in the Ottoman Empire

, writing detailed accounts of the practice in her letters, and enthusiastically promoted the procedure in England upon her return in 1718. In 1721, Cotton Mather and colleagues provoked controversy in Boston by inoculating hundreds. In 1796, Edward Jenner

, a doctor in Berkeley, Gloucestershire

, rural England, discovered that immunity to smallpox could be produced by inoculating a person with material from a cowpox

lesion. Cowpox is a poxvirus in the same family as variola. Jenner called the material used for inoculation vaccine

, from the root word

vacca, which is Latin

for cow. The procedure was much safer than variolation, and did not involve a risk of smallpox transmission. Vaccination to prevent smallpox was soon practiced all over the world. During the 19th century, the cowpox virus used for smallpox vaccination was replaced by vaccinia virus. Vaccinia is in the same family as cowpox and variola but is genetic

ally distinct from both. The origin of vaccinia virus and how it came to be in the vaccine are not known.

The current formulation of smallpox vaccine is a live virus preparation of infectious vaccinia virus. The vaccine is given using a bifurcated (two-pronged) needle that is dipped into the vaccine solution. The needle is used to prick the skin (usually the upper arm) a number of times in a few seconds. If successful, a red and itchy bump develops at the vaccine site in three or four days. In the first week, the bump becomes a large blister (called a “Jennerian vesicle”) which fills with pus, and begins to drain. During the second week, the blister begins to dry up and a scab forms. The scab falls off in the third week, leaving a small scar.

The current formulation of smallpox vaccine is a live virus preparation of infectious vaccinia virus. The vaccine is given using a bifurcated (two-pronged) needle that is dipped into the vaccine solution. The needle is used to prick the skin (usually the upper arm) a number of times in a few seconds. If successful, a red and itchy bump develops at the vaccine site in three or four days. In the first week, the bump becomes a large blister (called a “Jennerian vesicle”) which fills with pus, and begins to drain. During the second week, the blister begins to dry up and a scab forms. The scab falls off in the third week, leaving a small scar.

The antibodies induced by vaccinia vaccine are cross-protective for other orthopoxviruses, such as monkeypox, cowpox, and variola (smallpox) viruses. Neutralizing antibodies are detectable 10 days after first-time vaccination, and seven days after revaccination. Historically, the vaccine has been effective in preventing smallpox infection in 95% of those vaccinated. Smallpox vaccination provides a high level of immunity for three to five years and decreasing immunity thereafter. If a person is vaccinated again later, immunity lasts even longer. Studies of smallpox cases in Europe in the 1950s and 1960s demonstrated that the fatality rate among persons vaccinated less than 10 years before exposure was 1.3%; it was 7% among those vaccinated 11 to 20 years prior, and 11% among those vaccinated 20 or more years prior to infection. By contrast, 52% of unvaccinated persons died.

There are side effects and risks associated with the smallpox vaccine. In the past, about 1 out of 1,000 people vaccinated for the first time experienced serious, but non-life-threatening, reactions including toxic or allergic reaction at the site of the vaccination (erythema multiforme

), spread of the vaccinia virus to other parts of the body, and to other individuals. Potentially life-threatening reactions occurred in 14 to 500 people out of every 1 million people vaccinated for the first time. Based on past experience, it is estimated that 1 or 2 people in 1 million (0.000198%) who receive the vaccine may die as a result, most often the result of postvaccinial encephalitis

or severe necrosis

in the area of vaccination (called progressive vaccinia).

Given these risks, as smallpox became effectively eradicated and the number of naturally occurring cases fell below the number of vaccine-induced illnesses and deaths, routine childhood vaccination was discontinued in the United States in 1972, and was abandoned in most European countries in the early 1970s. Routine vaccination of health care workers was discontinued in the U.S. in 1976, and among military recruits in 1990 (although military personnel deploying to the Middle East and Korea still receive the vaccination.) By 1986, routine vaccination had ceased in all countries. It is now primarily recommended for laboratory workers at risk for occupational exposure.

. People with semi-confluent and confluent types of smallpox may have therapeutic issues similar to patients with extensive skin burn

s.

No drug is currently approved for the treatment of smallpox. However, antiviral

treatments have improved since the last large smallpox epidemics, and studies suggest that the antiviral drug cidofovir

might be useful as a therapeutic agent. The drug must be administered intravenously, however, and may cause serious kidney toxicity.

In fatal cases of ordinary smallpox, death usually occurs between the tenth and sixteenth days of the illness. The cause of death from smallpox is not clear, but the infection is now known to involve multiple organs. Circulating immune complex

es, overwhelming viremia

, or an uncontrolled immune response may be contributing factors. In early hemorrhagic smallpox, death occurs suddenly about six days after the fever develops. Cause of death in hemorrhagic cases involved heart failure, sometimes accompanied by pulmonary edema

. In late hemorrhagic cases, high and sustained viremia, severe platelet

loss and poor immune response were often cited as causes of death. In flat smallpox modes of death are similar to those in burns, with loss of fluid, protein and electrolyte

s beyond the capacity of the body to replace or acquire, and fulminating sepsis

.

and range from simple bronchitis

to fatal pneumonia

. Respiratory

complications tend to develop on about the eighth day of the illness and can be either viral or bacterial in origin. Secondary bacteria

l infection of the skin is a relatively uncommon complication of smallpox. When this occurs, the fever usually remains elevated.

Other complications include encephalitis

(1 in 500 patients), which is more common in adults and may cause temporary disability; permanent pitted scars, most notably on the face; and complications involving the eyes (2% of all cases). Pustules can form on the eyelid, conjunctiva

, and cornea

, leading to complications such as conjunctivitis

, keratitis

, corneal ulcer

, iritis

, iridocyclitis

, and optic atrophy

. Blindness

results in approximately 35% to 40% of eyes affected with keratitis and corneal ulcer. Hemorrhagic smallpox can cause subconjunctival and retina

l hemorrhages. In 2% to 5% of young children with smallpox, virions reach the joints and bone, causing osteomyelitis

variolosa. Lesions are symmetrical, most common in the elbows, tibia

, and fibula, and characteristically cause separation of an epiphysis

and marked periosteal

reactions. Swollen joints limit movement, and arthritis

may lead to limb deformities, ankylosis

, malformed bones, flail joints, and stubby fingers.

Smallpox probably diverged from an ancestral African rodent-borne variola-like virus between 16,000 and 68,000 years ago. The more severe form (variola major) is thought to have originated in Asia between 400 and 1600 years ago. Alastrim minor, a second form found in West Africa

Smallpox probably diverged from an ancestral African rodent-borne variola-like virus between 16,000 and 68,000 years ago. The more severe form (variola major) is thought to have originated in Asia between 400 and 1600 years ago. Alastrim minor, a second form found in West Africa

and the Americas, is thought to have evolved between 1,400 and 6,300 years ago. This clade

gave rise to two subclades that diverged at least 800 years ago.

mummy

of Ramses V who died over 3000 years ago (1145 BCE). Historical records from Asia describe evidence of smallpox-like disease in medical writings from ancient India (as early as 1500 BCE) and China (1122 BCE). It has been speculated that Egyptian traders brought smallpox to India during the 1st millennium BC, where it remained as an endemic human disease for at least 2000 years. Smallpox was probably introduced in China during the 1st century AD from the southwest, and in the 6th century was carried from China to Japan. In Japan, the epidemic of 735–737 is believed to have killed up to one-third of the population. At least seven religious deities have been specifically dedicated to smallpox, such as the god Sopona

in the Yoruba religion. In India, the Hindu goddess of smallpox, Sitala Mata

, was worshiped in temples throughout the country.

The arrival of smallpox in Europe and south-western Asia is less clear. Smallpox is not described in either the Old

or New Testament

s of the Bible, or in literature of the Greeks and Romans. Scholars agree it is very unlikely such a serious disease as variola major would have escaped a description by Hippocrates

if it existed in the Mediterranean region. While the Antonine Plague

that swept through the Roman Empire

in 165–180 AD may have been caused by smallpox, other historians speculate that Arab

armies first carried smallpox out of Africa to Southwestern Europe during the 7th and 8th centuries AD. In the 9th century the Persian physician

, Rhazes, provided one of the most definitive observations of smallpox and was the first to differentiate smallpox from measles

and chickenpox

in his Kitab fi al-jadari wa-al-hasbah (The Book of Smallpox and Measles). During the Middle Ages

, smallpox made periodic incursions into Europe but did not become established there until the population increased and population movement became more active during the time of the Crusades

. By the 16th century smallpox was well established over most of Europe. With its introduction in populated areas in India, China and Europe, smallpox affected mainly children, with periodic epidemics that killed up to 30% of those infected. The appearance of smallpox in Europe is of particular importance, as successive waves of European exploration and colonization served to spread the disease to other parts of the world. By the 16th century it had become an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the known world.

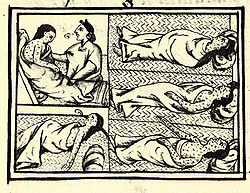

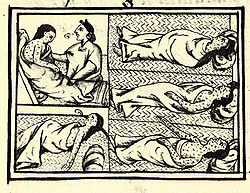

There are no credible descriptions of smallpox-like disease in the Americas

There are no credible descriptions of smallpox-like disease in the Americas

before the westward exploration by Europeans in the 15th century AD. In 1507 smallpox was introduced into the Caribbean island of Hispaniola

and to the mainland in 1520, when Spanish settlers from Hispaniola arriving in Mexico brought smallpox with them. Smallpox devastated the native Amerindian population and was an important factor in the conquest of the Aztec

s and the Incas by the Spaniards. Settlement of the east coast of North America in 1633 in Plymouth, Massachusetts was also accompanied by devastating outbreaks of smallpox among Native American populations, and subsequently among the native-born colonists. Some estimates indicate case fatality rates of 80–90% in Native American populations during smallpox epidemics. Smallpox was introduced into Australia

in 1789 and again in 1829. Although the disease was never endemic on the continent, it was the principal cause of death in Aboriginal

populations between 1780 and 1870.

By the mid-18th century smallpox was a major endemic disease

everywhere in the world except in Australia and in several small islands. In Europe smallpox was a leading cause of death in the 18th century, killing an estimated 400,000 Europeans each year. Through the century smallpox resulted in the deaths of perhaps 10% of all the infants of Sweden

every year, and the death rate of infants in Russia

may have been even higher. The widespread use of variolation in a few countries, notably Great Britain, its North American colonies, and China, somewhat reduced the impact of smallpox among the wealthy classes during the latter part of the 18th century, but a real reduction in its incidence did not occur until vaccination became a common practice toward the end of the 19th century. Improved vaccines and the practice of re-vaccination led to a substantial reduction in cases in Europe and North America, but smallpox remained almost unchecked everywhere else in the world. In the United States and South Africa a much milder form of smallpox, variola minor, was recognized just before the close of the 19th century. By the mid-20th century variola minor occurred along with variola major, in varying proportions, in many parts of Africa. Patients with variola minor experience only a mild systemic illness, are often ambulant

throughout the course of the disease, and are therefore able to more easily spread disease. Infection with v. minor induces immunity against the more deadly variola major form. Thus as v. minor spread all over the USA, into Canada, the South American countries and Great Britain it became the dominant form of smallpox, further reducing mortality rates.

Since Jenner demonstrated the effectiveness of cowpox to protect humans from smallpox in 1796, various attempts were made to eliminate smallpox on a regional scale. As early as 1803, the Spanish Crown organized a mission (the Balmis expedition

Since Jenner demonstrated the effectiveness of cowpox to protect humans from smallpox in 1796, various attempts were made to eliminate smallpox on a regional scale. As early as 1803, the Spanish Crown organized a mission (the Balmis expedition

) to transport the vaccine to the Spanish colonies

in the Americas and the Philippines, and establish mass vaccination programs there. The US Congress passed the Vaccine Act of 1813

to ensure that safe smallpox vaccine would be available to the American public. By about 1817, a very solid state vaccination program existed in the Dutch East Indies

. In British India a program was launched to propagate smallpox vaccination, through Indian vaccinators, under the supervision of European officials. Nevertheless, British vaccination efforts in India, and in Burma in particular, were hampered by stubborn indigenous preference for inoculation and distrust of vaccination, despite tough legislation, improvements in the local efficacy of the vaccine and vaccine preservative, and education efforts. By 1832, the federal government of the United States established a smallpox vaccination program for Native Americans. In 1842, the United Kingdom banned inoculation, later progressing to mandatory vaccination

. The British government introduced compulsory smallpox vaccination by an Act of Parliament in 1853. In the United States, from 1843 to 1855 first Massachusetts, and then other states required smallpox vaccination. Although some disliked these measures, coordinated efforts against smallpox went on, and the disease continued to diminish in the wealthy countries. By 1897, smallpox had largely been eliminated from the United States. In Northern Europe a number of countries had eliminated smallpox by 1900, and by 1914, the incidence in most industrialized countries had decreased to comparatively low levels. Vaccination continued in industrialized countries, until the mid to late 1970s as protection against reintroduction. Australia and New Zealand are two notable exceptions; neither experienced endemic smallpox and never vaccinated widely, relying instead on protection by distance and strict quarantines.

The first hemisphere

-wide effort to eradicate smallpox was made in 1950 by the Pan American Health Organization

. The campaign was successful in eliminating smallpox from all American countries except Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Ecuador. In 1958 Professor Viktor Zhdanov

, Deputy Minister of Health for the USSR

, called on the World Health Assembly

to undertake a global initiative to eradicate

smallpox. The proposal (Resolution WHA11.54) was accepted in 1959. At this point, 2 million people were dying from smallpox every year. Overall, however, the progress towards eradication was disappointing, especially in Africa and in the Indian subcontinent

. In 1966 an international team, the Smallpox Eradication Unit, was formed under the leadership of an American, Donald Henderson

. In 1967, the World Health Organization intensified the global smallpox eradication by contributing $2.4 million annually to the effort, and adopted the new disease surveillance method promoted by Czech epidemiologist Karel Raška

.

In the early 1950s an estimated 50 million cases of smallpox occurred in the world each year. To eradicate smallpox, each outbreak had to be stopped from spreading, by isolation of cases and vaccination of everyone who lived close by. This process is known as "ring vaccination". The key to this strategy was monitoring of cases in a community (known as surveillance) and containment. The initial problem the WHO team faced was inadequate reporting of smallpox cases, as many cases did not come to the attention of the authorities. The fact that humans are the only reservoir for smallpox infection, and that carriers

did not exist, played a significant role in the eradication of smallpox. The WHO established a network of consultants who assisted countries in setting up surveillance and containment activities. Early on donations of vaccine were provided primarily by the Soviet Union and the United States, but by 1973, more than 80% of all vaccine was produced in developing countries.

The last major European outbreak of smallpox was in 1972 in Yugoslavia

, after a pilgrim from Kosovo

returned from the Middle East, where he had contracted the virus. The epidemic infected 175 people, causing 35 deaths. Authorities declared martial law

, enforced quarantine, and undertook widespread re-vaccination of the population, enlisting the help of the WHO. In two months, the outbreak was over. Prior to this, there had been a smallpox outbreak in May–July 1963 in Stockholm

, Sweden, brought from the Far East

by a Swedish sailor; this had been dealt with by quarantine measures and vaccination of the local population.

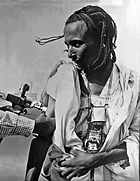

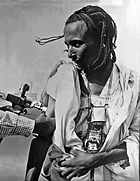

By the end of 1975, smallpox persisted only in the Horn of Africa

. Conditions were very difficult in Ethiopia and Somalia, where there were few roads. Civil war, famine, and refugees made the task even more difficult. An intensive surveillance and containment and vaccination program was undertaken in these countries in early and mid-1977, under the direction of Australian microbiologist Frank Fenner

. As the campaign neared its goal, Fenner and his team played an important role in verifying eradication. The last naturally occurring case of indigenous smallpox (Variola minor) was diagnosed in Ali Maow Maalin

, a hospital cook in Merca, Somalia

, on 26 October 1977. The last naturally occurring case of the more deadly Variola major had been detected in October 1975 in a two-year-old Bangladesh

i girl, Rahima Banu

.

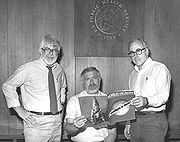

The global eradication of smallpox was certified, based on intense verification activities in countries, by a commission of eminent scientists on 9 December 1979 and subsequently endorsed by the World Health Assembly on 8 May 1980. The first two sentences of the resolution read:

The last cases of smallpox in the world occurred in an outbreak of two cases (one of which was fatal) in Birmingham

The last cases of smallpox in the world occurred in an outbreak of two cases (one of which was fatal) in Birmingham

, UK

in 1978. A medical photographer, Janet Parker

, contracted the disease at the University of Birmingham Medical School

and died on September 11, 1978, after which the scientist responsible for smallpox research at the university, Professor Henry Bedson, committed suicide

. In light of this accident, all known stocks of smallpox were destroyed or transferred to one of two WHO reference laboratories which had BSL-4 facilities; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC) in the United States and the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology VECTOR in Koltsovo

, Russia.

In 1986, the World Health Organization

first recommended destruction of the virus, and later set the date of destruction to be 30 December 1993. This was postponed to 30 June 1999. Due to resistance from the US and Russia, in 2002 the World Health Assembly agreed to permit the temporary retention of the virus stocks for specific research purposes. Destroying existing stocks would reduce the risk involved with ongoing smallpox research; the stocks are not needed to respond to a smallpox outbreak. Some scientists have argued that the stocks may be useful in developing new vaccines, antiviral drugs, and diagnostic tests, however, a 2010 review by a team of public health experts appointed by the World Health Organization

concluded that no essential public health purpose is served by the US and Russia continuing to retain virus stocks. The latter view is frequently supported in the scientific community, particularly among veterans of the WHO Smallpox Eradication Program.

In March 2004 smallpox scabs

were found tucked inside an envelope in a book on Civil War

medicine in Santa Fe, New Mexico

. The envelope was labeled as containing scabs from a vaccination and gave scientists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

an opportunity to study the history of smallpox vaccination in the US.

agent at the Siege of Fort Pitt during the French and Indian Wars

(1754–63) against France and its Native American

allies. Although it is not clear whether the actual use of smallpox had official sanction, on June 24, 1763, William Trent, a local trader, wrote, "Out of our regard for them [sc. representatives of the besieging Delawares], we gave them two Blankets and an Handkerchief out of the Small Pox Hospital. I hope it will have the desired effect." Historians do not agree on whether this effort to broadcast the disease was successful. It has also been alleged that smallpox was used as a weapon during the American Revolutionary War

(1775–83).

During World War II

, scientists from the United Kingdom, United States and Japan were involved in research into producing a biological weapon from smallpox. Plans of large scale production were never carried through as they considered that the weapon would not be very effective due to the wide-scale availability of a vaccine

.

In 1947 the Soviet Union

established a smallpox weapons factory in the city of Zagorsk, 75 km to the northeast of Moscow. An outbreak of weaponized smallpox possibly occurred during testing at the factory in the 1970s. General Prof. Peter Burgasov, former Chief Sanitary Physician of the Soviet Army

and a senior researcher within the Soviet program of biological weapons

, described the incident:

Others contend that the first patient may have contracted the disease while visiting Uyaly or Komsomolsk

, two cities where the boat docked.

Responding to international pressures, in 1991 the Soviet government allowed a joint US-British inspection team to tour four of its main weapons facilities at Biopreparat

. The inspectors were met with evasion and denials from the Soviet scientists, and were eventually ordered out of the facility. In 1992 Soviet defector Ken Alibek

alleged that the Soviet bioweapons program at Zagorsk had produced a large stockpile—as much as twenty tons—of weaponized smallpox (possibly engineered to resist vaccines, Alibek further alleged), along with refrigerated warhead

s to deliver it. Alibek's stories about the former Soviet program's smallpox activities have never been independently verified.

In 1997, the Russian government announced that all of its remaining smallpox samples would be moved to the Vector Institute in Koltsovo

. With the breakup of the Soviet Union and unemployment of many of the weapons program's scientists, US government officials have expressed concern that smallpox and the expertise to weaponize it may have become available to other governments or terrorist groups who might wish to use virus as means of biological warfare. Specific allegations made against Iraq in this respect, however, proved to be false.

Concern has been expressed by some that artificial gene synthesis could be used recreate the virus from existing digital genomes, for use in biological warfare. Insertion of the synthesized smallpox DNA into existing related pox viruses could theoretically be used to recreate the virus. The first step to mitigating this risk, it has been suggested, should be to destroy the remaining virus stocks so as to enable unequivocal criminalization of any possession of the virus.

, Ramses V of Egypt

, the Kangxi Emperor

(survived), Shunzhi Emperor

and Tongzhi Emperor

(refer to the official history) of China, Date Masamune

of Japan (who lost an eye to the disease). Cuitláhuac

, the 10th tlatoani

(ruler) of the Aztec

city of Tenochtitlan, died of smallpox in 1520, shortly after its introduction to the Americas

, and the Incan emperor Huayna Capac

died of it in 1527. More recent public figures include Guru Har Krishan

, 8th Guru of the Sikhs, in 1664, Peter II of Russia

in 1730 (died),George Washington

(survived), king Louis XV in 1774 (died) and Maximilian III Joseph, Elector of Bavaria in 1777.

Prominent families throughout the world often had several people infected by and/or perish from the disease. For example, several relatives of Henry VIII

survived the disease but were scarred by it. These include his sister Margaret, Queen of Scotland

, his fourth wife, Anne of Cleves

, and his two daughters: Mary I of England

in 1527 and Elizabeth I of England

in 1562 (as an adult she would often try to disguise the pockmarks with heavy makeup). His great-niece, Mary, Queen of Scots, contracted the disease as a child but had no visible scarring.

In Europe, deaths from smallpox often changed dynastic succession. The only surviving son of Henry VIII

, Edward VI

, died from complications shortly after apparently recovering from the disease, thereby rendering his sire's infamous efforts to provide England with a male heir moot. (His immediate successors were all females.) Louis XV of France

succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV through a series of deaths of smallpox or measles among those earlier in the succession line. He himself died of the disease in 1774. William III

lost his mother to the disease when he was only ten years old in 1660, and named his uncle Charles

as legal guardian: her death from smallpox would indirectly spark a chain of events that would eventually lead to the permanent ousting of the Stuart line from the British throne. William III's wife, Mary II of England

, died from smallpox as well.

In China, the Qing Dynasty

had extensive protocols to protect Manchu

s from the Peking's endemic smallpox. Most notably, the Kangxi Emperor

was promoted to the throne because he had survived the disease, ahead of older brothers who had not yet had it.

U.S. Presidents George Washington

, Andrew Jackson

, and Abraham Lincoln

all contracted and recovered from the disease. Washington became infected with smallpox on a visit to Barbados in 1751. Jackson developed the illness after being taken prisoner by the British during the American Revolution, and though he recovered, his brother Robert did not. Lincoln contracted the disease during his Presidency, possibly from his son Tad, and was quarantined shortly after giving the Gettysburg address in 1863.

Famous theologian Jonathan Edwards died of smallpox in 1758 following an inoculation.

U.S.S.R. leader Joseph Stalin

fell ill with smallpox at the age of seven. His face was badly scarred by the disease. He later had photographs retouched to make his pockmarks less apparent.

Hungarian poet Ferenc Kölcsey

, who wrote the Hungarian national anthem, lost his right eye to smallpox.

Infectious disease

Infectious diseases, also known as communicable diseases, contagious diseases or transmissible diseases comprise clinically evident illness resulting from the infection, presence and growth of pathogenic biological agents in an individual host organism...

unique to humans, caused by either of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor. The disease is also known by the Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

names Variola or Variola vera, which is a derivative of the Latin varius, meaning "spotted", or varus, meaning "pimple". The term "smallpox" was first used in Europe in the 15th century to distinguish variola from the "great pox" (syphilis

Syphilis

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the spirochete bacterium Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum. The primary route of transmission is through sexual contact; however, it may also be transmitted from mother to fetus during pregnancy or at birth, resulting in congenital syphilis...

).

Smallpox localizes in small blood vessel

Blood vessel

The blood vessels are the part of the circulatory system that transports blood throughout the body. There are three major types of blood vessels: the arteries, which carry the blood away from the heart; the capillaries, which enable the actual exchange of water and chemicals between the blood and...

s of the skin and in the mouth and throat. In the skin, this results in a characteristic maculopapular rash, and later, raised fluid-filled blister

Blister

A blister is a small pocket of fluid within the upper layers of the skin, typically caused by forceful rubbing , burning, freezing, chemical exposure or infection. Most blisters are filled with a clear fluid called serum or plasma...

s. V. major produces a more serious disease and has an overall mortality rate

Mortality rate

Mortality rate is a measure of the number of deaths in a population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit time...

of 30–35%. V. minor causes a milder form of disease (also known as alastrim

Alastrim

Alastrim, also known as variola minor, is the milder strain of the variola virus that causes smallpox.Variola minor is of the genus orthopoxvirus, which are DNA viruses that replicate in the cytoplasm of the affected cell, rather than in its nucleus...

, cottonpox, milkpox, whitepox, and Cuban itch) which kills about 1% of its victims. Long-term complications of V. major infection include characteristic scars, commonly on the face, which occur in 65–85% of survivors. Blindness

Blindness

Blindness is the condition of lacking visual perception due to physiological or neurological factors.Various scales have been developed to describe the extent of vision loss and define blindness...

resulting from corneal ulcer

Corneal ulcer

A corneal ulcer, or ulcerative keratitis, is an inflammatory condition of the cornea involving loss of its outer layer. It is very common in dogs and is sometimes seen in cats...

ation and scarring, and limb deformities due to arthritis and osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis simply means an infection of the bone or bone marrow...

are less common complications, seen in about 2–5% of cases.

Smallpox is believed to have emerged in human populations about 10,000 BC. The earliest physical evidence of smallpox is probably the pustular rash on the mummified body of Pharaoh Ramses V of Egypt. The disease killed an estimated 400,000 Europeans per year during the closing years of the 18th century (including five reigning monarch

Monarch

A monarch is the person who heads a monarchy. This is a form of government in which a state or polity is ruled or controlled by an individual who typically inherits the throne by birth and occasionally rules for life or until abdication...

s), and was responsible for a third of all blindness. Of all those infected, 20–60%—and over 80% of infected children—died from the disease. Smallpox was responsible for an estimated 300–500 million deaths during the 20th century. As recently as 1967, the World Health Organization

World Health Organization

The World Health Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations that acts as a coordinating authority on international public health. Established on 7 April 1948, with headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, the agency inherited the mandate and resources of its predecessor, the Health...

(WHO) estimated that 15 million people contracted the disease and that two million died in that year.

After vaccination

Vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of antigenic material to stimulate the immune system of an individual to develop adaptive immunity to a disease. Vaccines can prevent or ameliorate the effects of infection by many pathogens...

campaigns throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the WHO certified the eradication of smallpox in 1979. Smallpox is one of the two infectious disease

Infectious disease

Infectious diseases, also known as communicable diseases, contagious diseases or transmissible diseases comprise clinically evident illness resulting from the infection, presence and growth of pathogenic biological agents in an individual host organism...

s to have been eradicated, the other being rinderpest

Rinderpest

Rinderpest was an infectious viral disease of cattle, domestic buffalo, and some other species of even-toed ungulates, including buffaloes, large antelopes and deer, giraffes, wildebeests and warthogs. After a global eradication campaign, the last confirmed case of rinderpest was diagnosed in 2001...

, which was declared eradicated in 2011.

Classification

There are two clinical forms of smallpox. Variola major is the severe and most common form, with a more extensive rash and higher fever. Variola minorAlastrim

Alastrim, also known as variola minor, is the milder strain of the variola virus that causes smallpox.Variola minor is of the genus orthopoxvirus, which are DNA viruses that replicate in the cytoplasm of the affected cell, rather than in its nucleus...

is a less common presentation, and a much less severe disease, with historical death rates of 1% or less. Subclinical (asymptomatic

Asymptomatic

In medicine, a disease is considered asymptomatic if a patient is a carrier for a disease or infection but experiences no symptoms. A condition might be asymptomatic if it fails to show the noticeable symptoms with which it is usually associated. Asymptomatic infections are also called subclinical...

) infections with variola virus have been noted, but are not common. In addition, a form called variola sine eruptione (smallpox without rash) is seen generally in vaccinated persons. This form is marked by a fever that occurs after the usual incubation period and can be confirmed only by antibody studies or, rarely, by virus isolation.

Signs and symptoms

Incubation period

Incubation period is the time elapsed between exposure to a pathogenic organism, a chemical or radiation, and when symptoms and signs are first apparent...

between contraction and the first obvious symptoms of the disease is around 12 days. Once inhaled, variola major virus invades the oropharyngeal (mouth and throat) or the respiratory mucosa, migrates to regional lymph nodes, and begins to multiply. In the initial growth phase the virus seems to move from cell to cell, but around the 12th day, lysis

Lysis

Lysis refers to the breaking down of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a "lysate"....

of many infected cells occurs and the virus is found in the blood

Blood

Blood is a specialized bodily fluid in animals that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells....

stream in large numbers (this is called viremia

Viremia

Viremia is a medical condition where viruses enter the bloodstream and hence have access to the rest of the body. It is similar to bacteremia, a condition where bacteria enter the bloodstream.- Primary versus Secondary :...

), and a second wave of multiplication occurs in the spleen, bone marrow

Bone marrow

Bone marrow is the flexible tissue found in the interior of bones. In humans, bone marrow in large bones produces new blood cells. On average, bone marrow constitutes 4% of the total body mass of humans; in adults weighing 65 kg , bone marrow accounts for approximately 2.6 kg...

, and lymph nodes. The initial or prodromal symptoms are similar to other viral diseases such as influenza

Influenza

Influenza, commonly referred to as the flu, is an infectious disease caused by RNA viruses of the family Orthomyxoviridae , that affects birds and mammals...

and the common cold

Common cold

The common cold is a viral infectious disease of the upper respiratory system, caused primarily by rhinoviruses and coronaviruses. Common symptoms include a cough, sore throat, runny nose, and fever...

: fever

Fever

Fever is a common medical sign characterized by an elevation of temperature above the normal range of due to an increase in the body temperature regulatory set-point. This increase in set-point triggers increased muscle tone and shivering.As a person's temperature increases, there is, in...

of at least 38.5 °C (101 °F), muscle pain

Myalgia

Myalgia means "muscle pain" and is a symptom of many diseases and disorders. The most common causes are the overuse or over-stretching of a muscle or group of muscles. Myalgia without a traumatic history is often due to viral infections...

, malaise, headache and prostration

Prostration

Prostration is the placement of the body in a reverentially or submissively prone position. Major world religions employ prostration either as a means of embodying reverence for a noble person, persons or doctrine, or as an act of submissiveness to a supreme being or beings...

. As the digestive tract

Gastrointestinal tract

The human gastrointestinal tract refers to the stomach and intestine, and sometimes to all the structures from the mouth to the anus. ....

is commonly involved, nausea and vomiting and backache often occur. The prodrome, or preeruptive stage, usually lasts 2–4 days. By days 12–15 the first visible lesions—small reddish spots called enanthem

Enanthem

Mucous membrane Rash arising from another focus of infection.Enanthem or enanthema are medical terms for a rash on the mucous membranes. These are characteristic of patients with smallpox, measles, and chicken pox....

—appear on mucous membranes of the mouth, tongue, palate

Palate

The palate is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity. A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but, in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly separate. The palate is divided into two parts, the anterior...

, and throat, and temperature falls to near normal. These lesions rapidly enlarge and rupture, releasing large amounts of virus into the saliva

Saliva

Saliva , referred to in various contexts as spit, spittle, drivel, drool, or slobber, is the watery substance produced in the mouths of humans and most other animals. Saliva is a component of oral fluid. In mammals, saliva is produced in and secreted from the three pairs of major salivary glands,...

.

Smallpox virus preferentially attacks skin cells, causing the characteristic pimples (called macules) associated with the disease. A rash develops on the skin 24 to 48 hours after lesions on the mucous membranes appear. Typically the macules first appear on the forehead, then rapidly spread to the whole face, proximal portions of extremities, the trunk, and lastly to distal portions of extremities. The process takes no more than 24 to 36 hours, after which no new lesions appear. At this point variola major infection can take several very different courses, resulting in four types of smallpox disease based on the Rao classification: ordinary, modified, malignant (or flat), and hemorrhagic. Historically, smallpox has an overall fatality rate of about 30%; however, the malignant and hemorrhagic forms are usually fatal.

Ordinary

Ninety percent or more of smallpox cases among unvaccinated persons are of the ordinary type. In this form of the disease, by the second day of the rash, the macules become raised papulePapule

A papule is a circumscribed, solid elevation of skin with no visible fluid, varying in size from a pinhead to 1 cm.With regard to the quote "...varying in size from a pinhead to 1cm," depending on which text is referenced, some authors state the cutoff between a papule and a plaque as 0.5cm,...

s. By the third or fourth day the papules fill with an opalescent fluid to become vesicles. This fluid becomes opaque

Opacity (optics)

Opacity is the measure of impenetrability to electromagnetic or other kinds of radiation, especially visible light. In radiative transfer, it describes the absorption and scattering of radiation in a medium, such as a plasma, dielectric, shielding material, glass, etc...

and turbid within 24–48 hours, giving them the appearance of pustules; however, the so-called pustules are filled with tissue debris, not pus.

By the sixth or seventh day, all the skin lesions have become pustules. Between 7 and 10 days the pustules mature and reach their maximum size. The pustules are sharply raised, typically round, tense, and firm to the touch. The pustules are deeply embedded in the dermis, giving them the feel of a small bead in the skin. Fluid slowly leaks from the pustules, and by the end of the second week the pustules deflate, and start to dry up, forming crusts (or scabs). By day 16–20 scabs have formed over all the lesions, which have started to flake off, leaving depigmented

Depigmentation

Depigmentation is the lightening of the skin, or loss of pigment. Depigmentation of the skin can be caused by a number of local and systemic conditions. The pigment loss can be partial or complete...

scars.

Ordinary smallpox generally produces a discrete rash, in which the pustules stand out on the skin separately. The distribution of the rash is densest on the face; denser on the extremities than on the trunk; and on the extremities, denser on the distal parts than on the proximal. The palms of the hands and soles of the feet are involved in the majority of cases. Sometimes, the blisters merge together into sheets, forming a confluent rash, which begin to detach the outer layers of skin from the underlying flesh. Patients with confluent smallpox often remain ill even after scabs have formed over all the lesions. In one case series, the case-fatality rate in confluent smallpox was 62%.

Modified

Referring to the character of the eruption and the rapidity of its development, modified smallpox occurs mostly in previously vaccinated people. In this form the prodromal illness still occurs but may be less severe than in the ordinary type. There is usually no fever during evolution of the rash. The skin lesions tend to be fewer and evolve more quickly, are more superficial, and may not show the uniform characteristic of more typical smallpox. Modified smallpox is rarely, if ever, fatal. This form of variola major is more easily confused with chickenpoxChickenpox

Chickenpox or chicken pox is a highly contagious illness caused by primary infection with varicella zoster virus . It usually starts with vesicular skin rash mainly on the body and head rather than at the periphery and becomes itchy, raw pockmarks, which mostly heal without scarring...

.

Malignant

In malignant-type smallpox (also called flat smallpox) the lesions remain almost flush with the skin at the time when raised vesicles form in the ordinary type. It is unknown why some people develop this type. Historically, it accounted for 5%–10% of cases, and the majority (72%) were children. Malignant smallpox is accompanied by a severe prodromal phase that lasts 3–4 days, prolonged high fever, and severe symptoms of toxemiaToxemia

Toxemia may refer to:* A generic term for the presence of toxins in the blood, see Bacteremia* An outdated medical term for Pre-eclampsia...

. The rash on the tongue and palate is extensive. Skin lesions mature slowly and by the seventh or eighth day they are flat and appear to be buried in the skin. Unlike ordinary-type smallpox, the vesicles contain little fluid, are soft and velvety to the touch, and may contain hemorrhages. Malignant smallpox is nearly always fatal.

Hemorrhagic

Hemorrhagic smallpox is a severe form that is accompanied by extensive bleeding into the skin, mucous membranes, and gastrointestinal tract. This form develops in approximately 2% of infections and occurred mostly in adults. In hemorrhagic smallpox the skin does not blister, but remains smooth. Instead, bleeding occurs under the skin, making it look charred and black, hence this form of the disease is also known as black poxBlack Pox

Black pox is a symptom of smallpox that is caused by bleeding under the skin which makes the skin look charred or black. It was more common in teenagers. This symptom usually indicates that a patient with smallpox is going to die....

.

In the early, or fulminating form, hemorrhaging appears on the second or third day as sub-conjunctival bleeding turns the whites of the eyes deep red. Hemorrhagic smallpox also produces a dusky erythema

Erythema

Erythema is redness of the skin, caused by hyperemia of the capillaries in the lower layers of the skin. It occurs with any skin injury, infection, or inflammation...

, petechiae, and hemorrhages in the spleen, kidney, serosa, muscle, and, rarely, the epicardium

Epicardium

Epicardium describes the outer layer of heart tissue . When considered as a part of the pericardium, it is the inner layer, or visceral pericardium, continuous with the serous layer....

, liver

Liver

The liver is a vital organ present in vertebrates and some other animals. It has a wide range of functions, including detoxification, protein synthesis, and production of biochemicals necessary for digestion...

, testes, ovaries and bladder

Bladder

Bladder usually refers to an anatomical hollow organBladder may also refer to:-Biology:* Urinary bladder in humans** Urinary bladder ** Bladder control; see Urinary incontinence** Artificial urinary bladder, in humans...

. Death often occurs suddenly between the fifth and seventh days of illness, when only a few insignificant skin lesions are present. A later form of the disease occurs in patients who survive for 8–10 days. The hemorrhages appear in the early eruptive period, and the rash is flat and does not progress beyond the vesicular stage. Patients in the early stage of disease show a decrease in coagulation factors (e.g. platelet

Platelet

Platelets, or thrombocytes , are small,irregularly shaped clear cell fragments , 2–3 µm in diameter, which are derived from fragmentation of precursor megakaryocytes. The average lifespan of a platelet is normally just 5 to 9 days...

s, prothrombin, and globulin

Globulin

Globulin is one of the three types of serum proteins, the others being albumin and fibrinogen. Some globulins are produced in the liver, while others are made by the immune system. The term globulin encompasses a heterogeneous group of proteins with typical high molecular weight, and both...

) and an increase in circulating antithrombin

Antithrombin

Antithrombin is a small protein molecule that inactivates several enzymes of the coagulation system. Antithrombin is a glycoprotein produced by the liver and consists of 432 amino acids. It contains three disulfide bonds and a total of four possible glycosylation sites...

. Patients in the late stage have significant thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia is a relative decrease of platelets in blood.A normal human platelet count ranges from 150,000 to 450,000 platelets per microliter of blood. These limits are determined by the 2.5th lower and upper percentile, so values outside this range do not necessarily indicate disease...

; however, deficiency of coagulation factors is less severe. Some in the late stage also show increased antithrombin. This form of smallpox occurs in anywhere from 3 to 25% of fatal cases depending on the virulence of the smallpox strain. Hemorrhagic smallpox is usually fatal.

Cause

Smallpox is caused by infection with variola virus, which belongs to the genus OrthopoxvirusOrthopoxvirus

Orthopoxvirus is a genus of poxviruses that includes many species isolated from mammals, such as Camelpox virus, Cowpox virus, Ectromelia virus, Monkeypox virus, and Volepox virus, which causes mousepox. The most famous member of the genus is Variola virus, which causes smallpox...

, the family Poxviridae

Poxviridae

Poxviruses are viruses that can, as a family, infect both vertebrate and invertebrate animals.Four genera of poxviruses may infect humans: orthopox, parapox, yatapox, molluscipox....

and subfamily chordopoxvirinae. Variola is a large brick-shaped virus measuring approximately 302 to 350 nanometers by 244 to 270 nm, with a single linear double stranded DNA genome

Genome

In modern molecular biology and genetics, the genome is the entirety of an organism's hereditary information. It is encoded either in DNA or, for many types of virus, in RNA. The genome includes both the genes and the non-coding sequences of the DNA/RNA....

186 kilobase pairs (kbp) in size and containing a hairpin loop at each end. The two classic varieties of smallpox are variola major and variola minor.

Four orthopoxviruses cause infection in humans: variola, vaccinia

Vaccinia

Vaccinia virus is a large, complex, enveloped virus belonging to the poxvirus family. It has a linear, double-stranded DNA genome approximately 190 kbp in length, and which encodes for approximately 250 genes. The dimensions of the virion are roughly 360 × 270 × 250 nm, with a mass of...

, cowpox

Cowpox

Cowpox is a skin disease caused by a virus known as the Cowpox virus. The pox is related to the vaccinia virus and got its name from the distribution of the disease when dairymaids touched the udders of infected cows. The ailment manifests itself in the form of red blisters and is transmitted by...

, and monkeypox

Monkeypox

Monkeypox also known as cockpox is an exotic infectious disease caused by the monkeypox virus. The disease was first identified in laboratory monkeys, hence its name, but in its natural state it seems to infect rodents more often than primates...

. Variola virus infects only humans in nature, although primates and other animals have been infected in a laboratory setting. Vaccinia, cowpox, and monkeypox viruses can infect both humans and other animals in nature.

The lifecycle of poxviruses is complicated by having multiple infectious forms, with differing mechanisms of cell entry. Poxviruses are unique among DNA viruses in that they replicate in the cytoplasm

Cytoplasm

The cytoplasm is a small gel-like substance residing between the cell membrane holding all the cell's internal sub-structures , except for the nucleus. All the contents of the cells of prokaryote organisms are contained within the cytoplasm...

of the cell rather than in the nucleus

Cell nucleus

In cell biology, the nucleus is a membrane-enclosed organelle found in eukaryotic cells. It contains most of the cell's genetic material, organized as multiple long linear DNA molecules in complex with a large variety of proteins, such as histones, to form chromosomes. The genes within these...

. In order to replicate, poxviruses produce a variety of specialized proteins not produced by other DNA viruses, the most important of which is a viral-associated DNA-dependent RNA polymerase.

Both enveloped

Viral envelope

Many viruses have viral envelopes covering their protein capsids. The envelopes typically are derived from portions of the host cell membranes , but include some viral glycoproteins. Functionally, viral envelopes are used to help viruses enter host cells...

and unenveloped virions are infectious. The viral envelope is made of modified Golgi

Golgi

Golgi may refer to:*Camillo Golgi , Italian physician and scientist after which the following terms are named:**Golgi apparatus , an organelle in the eukaryotic cell...

membranes containing viral-specific polypeptides, including hemagglutinin

Hemagglutinin

Influenza hemagglutinin or haemagglutinin is a type of hemagglutinin found on the surface of the influenza viruses. It is an antigenic glycoprotein. It is responsible for binding the virus to the cell that is being infected...

. Infection with either variola major or variola minor confers immunity against the other.

Transmission

Transmission occurs through inhalation of airborneAirborne disease

Airborne diseases refers to any diseases which are caused by pathogenic microbial agents and transmitted through the air. These viruses and bacteria can be aerosolized through coughing, sneezing, laughing or through close personal contact...

variola virus, usually droplets expressed from the oral, nasal, or pharyngeal

Pharynx

The human pharynx is the part of the throat situated immediately posterior to the mouth and nasal cavity, and anterior to the esophagus and larynx. The human pharynx is conventionally divided into three sections: the nasopharynx , the oropharynx , and the laryngopharynx...

mucosa of an infected person. It is transmitted from one person to another primarily through prolonged face-to-face contact with an infected person, usually within a distance of 6 feet (1.8 m), but can also be spread through direct contact with infected bodily fluid

Bodily fluid

Body fluid or bodily fluids are liquids originating from inside the bodies of living people. They include fluids that are excreted or secreted from the body as well as body water that normally is not.Body fluids include:-Body fluids and health:...

s or contaminated objects (fomite

Fomite

A fomite is any inanimate object or substance capable of carrying infectious organisms and hence transferring them from one individual to another. A fomite can be anything...

s) such as bedding or clothing. Rarely, smallpox has been spread by virus carried in the air in enclosed settings such as buildings, buses, and trains. The virus can cross the placenta

Placenta

The placenta is an organ that connects the developing fetus to the uterine wall to allow nutrient uptake, waste elimination, and gas exchange via the mother's blood supply. "True" placentas are a defining characteristic of eutherian or "placental" mammals, but are also found in some snakes and...

, but the incidence of congenital smallpox is relatively low.

Smallpox is not notably infectious in the prodromal

Prodrome

In medicine, a prodrome is an early symptom that might indicate the start of a disease before specific symptoms occur. It is derived from the Greek word prodromos or precursor...

period and viral shedding is usually delayed until the appearance of the rash, which is often accompanied by lesion

Lesion

A lesion is any abnormality in the tissue of an organism , usually caused by disease or trauma. Lesion is derived from the Latin word laesio which means injury.- Types :...

s in the mouth and pharynx. The virus can be transmitted throughout the course of the illness, but is most frequent during the first week of the rash, when most of the skin lesions are intact. Infectivity wanes in 7 to 10 days when scabs form over the lesions, but the infected person is contagious until the last smallpox scab falls off.

Smallpox is highly contagious, but generally spreads more slowly and less widely than some other viral diseases, perhaps because transmission requires close contact and occurs after the onset of the rash. The overall rate of infection is also affected by the short duration of the infectious stage. In temperate

Temperate

In geography, temperate or tepid latitudes of the globe lie between the tropics and the polar circles. The changes in these regions between summer and winter are generally relatively moderate, rather than extreme hot or cold...

areas, the number of smallpox infections were highest during the winter and spring. In tropical areas, seasonal variation was less evident and the disease was present throughout the year. Age distribution of smallpox infections depends on acquired immunity. Vaccination

Vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of antigenic material to stimulate the immune system of an individual to develop adaptive immunity to a disease. Vaccines can prevent or ameliorate the effects of infection by many pathogens...

immunity

Immunity (medical)

Immunity is a biological term that describes a state of having sufficient biological defenses to avoid infection, disease, or other unwanted biological invasion. Immunity involves both specific and non-specific components. The non-specific components act either as barriers or as eliminators of wide...

declines over time and is probably lost in all but the most recently vaccinated populations. Smallpox is not known to be transmitted by insects or animals and there is no asymptomatic carrier

Asymptomatic carrier

An asymptomatic carrier is a person or other organism that has contracted an infectious disease, but who displays no symptoms. Although unaffected by the disease themselves, carriers can transmit it to others...

state.

Diagnosis

The clinical definition of smallpox is an illness with acute onset of fever greater than 101°F (38.3°C) followed by a rash characterized by firm, deep seated vesicles or pustules in the same stage of development without other apparent cause. If a clinical case is observed, smallpox is confirmed using laboratory tests.Microscopically

Microscope

A microscope is an instrument used to see objects that are too small for the naked eye. The science of investigating small objects using such an instrument is called microscopy...

, poxviruses produce characteristic cytoplasmic inclusions, the most important of which are known as Guarnieri bodies

Guarnieri bodies

B-type inclusions, formerly also called Guarnieri bodies are cellular features found upon microscopic inspection of epithelial cells of individuals suspected of having poxvirus . In cells stained with eosin, they appear as pink blobs in the cytoplasm of affected epithelial cells...

, and are the sites of viral replication

Viral replication

Viral replication is the term used by virologists to describe the formation of biological viruses during the infection process in the target host cells. Viruses must first get into the cell before viral replication can occur. From the perspective of the virus, the purpose of viral replication is...

. Guarnieri bodies are readily identified in skin biopsies stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and appear as pink blobs. They are found in virtually all poxvirus infections but the absence of Guarnieri bodies cannot be used to rule out smallpox. The diagnosis of an orthopoxvirus infection can also be made rapidly by electron microscopic examination of pustular fluid or scabs. However, all orthopoxviruses exhibit identical brick-shaped virions by electron microscopy.

Definitive laboratory identification of variola virus involves growing the virus on chorioallantoic membrane

Chorioallantoic membrane

The chorioallantoic membrane — also called the chorioallantois or abbreviated to CAM — is a vascular membrane found in eggs of some amniotes, such as birds and reptiles. It is formed by the fusion of the mesodermal layers of two developmental structures: the allantois and the chorion...

(part of a chicken embryo

Embryo

An embryo is a multicellular diploid eukaryote in its earliest stage of development, from the time of first cell division until birth, hatching, or germination...

) and examining the resulting pock lesions under defined temperature conditions. Strains may be characterized by polymerase chain reaction

Polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction is a scientific technique in molecular biology to amplify a single or a few copies of a piece of DNA across several orders of magnitude, generating thousands to millions of copies of a particular DNA sequence....

(PCR) and restriction fragment length polymorphism

Restriction fragment length polymorphism

In molecular biology, restriction fragment length polymorphism, or RFLP , is a technique that exploits variations in homologous DNA sequences. It refers to a difference between samples of homologous DNA molecules that come from differing locations of restriction enzyme sites, and to a related...

(RFLP) analysis. Serologic tests and enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), which measure variola virus-specific immunoglobulin and antigen have also been developed to assist in the diagnosis of infection.

Chickenpox

Chickenpox

Chickenpox or chicken pox is a highly contagious illness caused by primary infection with varicella zoster virus . It usually starts with vesicular skin rash mainly on the body and head rather than at the periphery and becomes itchy, raw pockmarks, which mostly heal without scarring...

was commonly confused with smallpox in the immediate post-eradication era. Chickenpox and smallpox can be distinguished by several methods. Unlike smallpox, chickenpox does not usually affect the palms and soles. Additionally, chickenpox pustules are of varying size due to variations in the timing of pustule eruption: smallpox pustules are all very nearly the same size since the viral effect progresses more uniformly. A variety of laboratory methods are available for detecting chickenpox in evaluation of suspected smallpox cases.

Prevention

Inoculation

Inoculation is the placement of something that will grow or reproduce, and is most commonly used in respect of the introduction of a serum, vaccine, or antigenic substance into the body of a human or animal, especially to produce or boost immunity to a specific disease...

(also known as variolation). Inoculation was possibly practiced in India as early as 1000 BC, and involved either nasal insufflation of powdered smallpox scabs, or scratching material from a smallpox lesion into the skin. However, the idea that inoculation originated in India has been challenged as few of the ancient Sanskrit

Sanskrit

Sanskrit , is a historical Indo-Aryan language and the primary liturgical language of Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism.Buddhism: besides Pali, see Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit Today, it is listed as one of the 22 scheduled languages of India and is an official language of the state of Uttarakhand...