Cell nucleus

Encyclopedia

Cell biology

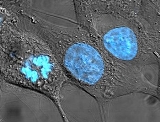

Cell biology is a scientific discipline that studies cells – their physiological properties, their structure, the organelles they contain, interactions with their environment, their life cycle, division and death. This is done both on a microscopic and molecular level...

, the nucleus (pl. nuclei; from Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

or , meaning kernel) is a membrane-enclosed organelle

Organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit within a cell that has a specific function, and is usually separately enclosed within its own lipid bilayer....

found in eukaryotic

Eukaryote

A eukaryote is an organism whose cells contain complex structures enclosed within membranes. Eukaryotes may more formally be referred to as the taxon Eukarya or Eukaryota. The defining membrane-bound structure that sets eukaryotic cells apart from prokaryotic cells is the nucleus, or nuclear...

cells

Cell (biology)

The cell is the basic structural and functional unit of all known living organisms. It is the smallest unit of life that is classified as a living thing, and is often called the building block of life. The Alberts text discusses how the "cellular building blocks" move to shape developing embryos....

. It contains most of the cell's genetic material

Genetics

Genetics , a discipline of biology, is the science of genes, heredity, and variation in living organisms....

, organized as multiple long linear DNA

DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid is a nucleic acid that contains the genetic instructions used in the development and functioning of all known living organisms . The DNA segments that carry this genetic information are called genes, but other DNA sequences have structural purposes, or are involved in...

molecules in complex with a large variety of protein

Protein

Proteins are biochemical compounds consisting of one or more polypeptides typically folded into a globular or fibrous form, facilitating a biological function. A polypeptide is a single linear polymer chain of amino acids bonded together by peptide bonds between the carboxyl and amino groups of...

s, such as histone

Histone

In biology, histones are highly alkaline proteins found in eukaryotic cell nuclei that package and order the DNA into structural units called nucleosomes. They are the chief protein components of chromatin, acting as spools around which DNA winds, and play a role in gene regulation...

s, to form chromosome

Chromosome

A chromosome is an organized structure of DNA and protein found in cells. It is a single piece of coiled DNA containing many genes, regulatory elements and other nucleotide sequences. Chromosomes also contain DNA-bound proteins, which serve to package the DNA and control its functions.Chromosomes...

s. The gene

Gene

A gene is a molecular unit of heredity of a living organism. It is a name given to some stretches of DNA and RNA that code for a type of protein or for an RNA chain that has a function in the organism. Living beings depend on genes, as they specify all proteins and functional RNA chains...

s within these chromosomes are the cell's nuclear genome

Genome

In modern molecular biology and genetics, the genome is the entirety of an organism's hereditary information. It is encoded either in DNA or, for many types of virus, in RNA. The genome includes both the genes and the non-coding sequences of the DNA/RNA....

. The function of the nucleus is to maintain the integrity of these genes and to control the activities of the cell by regulating gene expression

Gene expression

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product. These products are often proteins, but in non-protein coding genes such as ribosomal RNA , transfer RNA or small nuclear RNA genes, the product is a functional RNA...

— the nucleus is, therefore, the control center of the cell. The main structures making up the nucleus are the nuclear envelope

Nuclear envelope

A nuclear envelope is a double lipid bilayer that encloses the genetic material in eukaryotic cells. The nuclear envelope also serves as the physical barrier, separating the contents of the nucleus from the cytosol...

, a triple cell membrane and membrane that encloses the entire organelle and unifies its contents from the cellular cytoplasm

Cytoplasm

The cytoplasm is a small gel-like substance residing between the cell membrane holding all the cell's internal sub-structures , except for the nucleus. All the contents of the cells of prokaryote organisms are contained within the cytoplasm...

, and the nucleoskeleton (which includes nuclear lamina

Nuclear lamina

The nuclear lamina is a dense fibrillar network inside the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell. It is composed of intermediate filaments and membrane associated proteins. Besides providing mechanical support, the nuclear lamina regulates important cellular events such as DNA replication and cell division...

), a meshwork within the nucleus that adds mechanical support, much like the cytoskeleton

Cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a cellular "scaffolding" or "skeleton" contained within a cell's cytoplasm and is made out of protein. The cytoskeleton is present in all cells; it was once thought to be unique to eukaryotes, but recent research has identified the prokaryotic cytoskeleton...

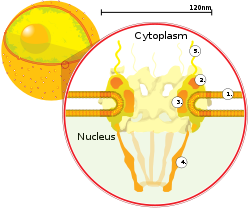

, which supports the cell as a whole. Because the nuclear membrane is impermeable to most molecules, nuclear pore

Nuclear pore

Nuclear pores are large protein complexes that cross the nuclear envelope, which is the double membrane surrounding the eukaryotic cell nucleus. There are about on average 2000 nuclear pore complexes in the nuclear envelope of a vertebrate cell, but it varies depending on cell type and the stage in...

s are required to allow movement of molecules across the envelope. These pores cross both of the membranes, providing a channel that allows free movement of small molecules and ion

Ion

An ion is an atom or molecule in which the total number of electrons is not equal to the total number of protons, giving it a net positive or negative electrical charge. The name was given by physicist Michael Faraday for the substances that allow a current to pass between electrodes in a...

s. The movement of larger molecules such as proteins is carefully controlled, and requires active transport regulated by carrier proteins. Nuclear transport

Nuclear transport

The entry and exit of large molecules from the cell nucleus is tightly controlled by the nuclear pore complexes . Although small molecules can enter the nucleus without regulation, macromolecules such as RNA and proteins require association with karyopherins called importins to enter the nucleus...

is crucial to cell function, as movement through the pores is required for both gene expression and chromosomal maintenance. The interior of the nucleus does not contain any membrane-bound subcompartments, its contents are not uniform, and a number of subnuclear bodies exist, made up of unique proteins, RNA

RNA

Ribonucleic acid , or RNA, is one of the three major macromolecules that are essential for all known forms of life....

molecules, and particular parts of the mitochondria. The best-known of these is the nucleolus

Nucleolus

The nucleolus is a non-membrane bound structure composed of proteins and nucleic acids found within the nucleus. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed and assembled within the nucleolus...

, which is mainly involved in the assembly of ribosome

Ribosome

A ribosome is a component of cells that assembles the twenty specific amino acid molecules to form the particular protein molecule determined by the nucleotide sequence of an RNA molecule....

s. After being produced in the nucleolus, ribosomes are exported to the cytoplasm where they translate mRNA.

History

Red blood cell

Red blood cells are the most common type of blood cell and the vertebrate organism's principal means of delivering oxygen to the body tissues via the blood flow through the circulatory system...

s of salmon

Salmon

Salmon is the common name for several species of fish in the family Salmonidae. Several other fish in the same family are called trout; the difference is often said to be that salmon migrate and trout are resident, but this distinction does not strictly hold true...

. Unlike mammalian red blood cells, those of other vertebrates still possess nuclei.

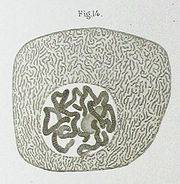

The nucleus was also described by Franz Bauer

Franz Bauer

Franz Andreas Bauer was an Austrian microscopist and botanical artist.Born in Feldsberg, Moravia , he was the son of Lucas Bauer , court painter to the Prince of Liechtenstein, and brother of the painters Josef Anton and Ferdinand Bauer...

in 1804 and in more detail in 1831 by Scottish botanist Robert Brown

Robert Brown (botanist)

Robert Brown was a Scottish botanist and palaeobotanist who made important contributions to botany largely through his pioneering use of the microscope...

in a talk at the Linnean Society of London

Linnean Society of London

The Linnean Society of London is the world's premier society for the study and dissemination of taxonomy and natural history. It publishes a zoological journal, as well as botanical and biological journals...

. Brown was studying orchids under microscope when he observed an opaque area, which he called the areola or nucleus, in the cells of the flower's outer layer.

He did not suggest a potential function. In 1838, Matthias Schleiden proposed that the nucleus plays a role in generating cells, thus he introduced the name "Cytoblast" (cell builder). He believed that he had observed new cells assembling around "cytoblasts". Franz Meyen

Franz Meyen

Franz Julius Ferdinand Meyen was a German physician and botanist.Meyen was born in Tilsit. In 1830 he wrote Phytotomie, the first review of plant anatomy...

was a strong opponent of this view, having already described cells multiplying by division and believing that many cells would have no nuclei. The idea that cells can be generated de novo, by the "cytoblast" or otherwise, contradicted work by Robert Remak

Robert Remak

-External links:*** in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science...

(1852) and Rudolf Virchow

Rudolf Virchow

Rudolph Carl Virchow was a German doctor, anthropologist, pathologist, prehistorian, biologist and politician, known for his advancement of public health...

(1855) who decisively propagated the new paradigm that cells are generated solely by cells ("Omnis cellula e cellula"). The function of the nucleus remained unclear.

Between 1877 and 1878, Oscar Hedwig published several studies on the fertilization of sea urchin

Sea urchin

Sea urchins or urchins are small, spiny, globular animals which, with their close kin, such as sand dollars, constitute the class Echinoidea of the echinoderm phylum. They inhabit all oceans. Their shell, or "test", is round and spiny, typically from across. Common colors include black and dull...

eggs, showing that the nucleus of the sperm

Sperm

The term sperm is derived from the Greek word sperma and refers to the male reproductive cells. In the types of sexual reproduction known as anisogamy and oogamy, there is a marked difference in the size of the gametes with the smaller one being termed the "male" or sperm cell...

enters the oocyte

Oocyte

An oocyte, ovocyte, or rarely ocyte, is a female gametocyte or germ cell involved in reproduction. In other words, it is an immature ovum, or egg cell. An oocyte is produced in the ovary during female gametogenesis. The female germ cells produce a primordial germ cell which undergoes a mitotic...

and fuses with its nucleus. This was the first time it was suggested that an individual develops from a (single) nucleated cell. This was in contradiction to Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Haeckel

The "European War" became known as "The Great War", and it was not until 1920, in the book "The First World War 1914-1918" by Charles à Court Repington, that the term "First World War" was used as the official name for the conflict.-Research:...

's theory that the complete phylogeny of a species would be repeated during embryonic development, including generation of the first nucleated cell from a "Monerula", a structureless mass of primordial mucus ("Urschleim"). Therefore, the necessity of the sperm nucleus for fertilization was discussed for quite some time. However, Hertwig confirmed his observation in other animal groups, e.g., amphibians and molluscs. Eduard Strasburger

Eduard Strasburger

Eduard Adolf Strasburger was a German professor who was one of the most famous botanists of the 19th century....

produced the same results for plants (1884). This paved the way to assign the nucleus an important role in heredity. In 1873, August Weismann

August Weismann

Friedrich Leopold August Weismann was a German evolutionary biologist. Ernst Mayr ranked him the second most notable evolutionary theorist of the 19th century, after Charles Darwin...

postulated the equivalence of the maternal and paternal germ cells for heredity. The function of the nucleus as carrier of genetic information became clear only later, after mitosis

Mitosis

Mitosis is the process by which a eukaryotic cell separates the chromosomes in its cell nucleus into two identical sets, in two separate nuclei. It is generally followed immediately by cytokinesis, which divides the nuclei, cytoplasm, organelles and cell membrane into two cells containing roughly...

was discovered and the Mendelian rules

Mendelian inheritance

Mendelian inheritance is a scientific description of how hereditary characteristics are passed from parent organisms to their offspring; it underlies much of genetics...

were rediscovered at the beginning of the 20th century; the chromosome theory of heredity was developed.

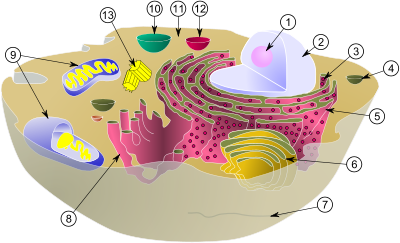

Structures

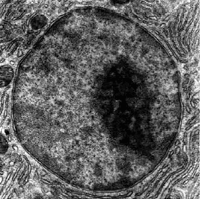

The nucleus is the largest cellular organelleOrganelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit within a cell that has a specific function, and is usually separately enclosed within its own lipid bilayer....

in animals.

In mammal

Mammal

Mammals are members of a class of air-breathing vertebrate animals characterised by the possession of endothermy, hair, three middle ear bones, and mammary glands functional in mothers with young...

ian cells, the average diameter of the nucleus is approximately 6 micrometers (μm), which occupies about 10% of the total cell volume. The viscous liquid within it is called nucleoplasm

Nucleoplasm

Similar to the cytoplasm of a cell, the nucleus contains nucleoplasm or karyoplasm. The nucleoplasm is one of the types of protoplasm, and it is enveloped by the nuclear membrane or nuclear envelope. The nucleoplasm is a highly viscous liquid that surrounds the chromosomes and nucleoli...

, and is similar in composition to the cytosol

Cytosol

The cytosol or intracellular fluid is the liquid found inside cells, that is separated into compartments by membranes. For example, the mitochondrial matrix separates the mitochondrion into compartments....

found outside the nucleus. It appears as a dense, roughly spherical organelle.

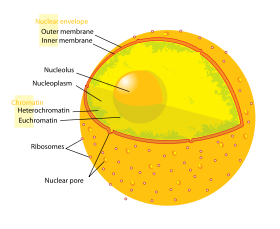

Nuclear envelope and pores

|

|

The outer envelope otherwise known as nuclear membrane consists of two cellular membranes

Cell membrane

The cell membrane or plasma membrane is a biological membrane that separates the interior of all cells from the outside environment. The cell membrane is selectively permeable to ions and organic molecules and controls the movement of substances in and out of cells. It basically protects the cell...

, an inner and an outer membrane, arranged parallel to one another and separated by 10 to 50 nanometers (nm). The nuclear envelope completely encloses the nucleus and separates the cell's genetic material from the surrounding cytoplasm, serving as a barrier to prevent macromolecule

Macromolecule

A macromolecule is a very large molecule commonly created by some form of polymerization. In biochemistry, the term is applied to the four conventional biopolymers , as well as non-polymeric molecules with large molecular mass such as macrocycles...

s from diffusing freely between the nucleoplasm and the cytoplasm. The outer nuclear membrane is continuous with the membrane of the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER), and is similarly studded with ribosomes. The space between the membranes is called the perinuclear space and is continuous with the RER lumen

Lumen (anatomy)

A lumen in biology is the inside space of a tubular structure, such as an artery or intestine...

.

Nuclear pores, which provide aqueous channels through the envelope, are composed of multiple proteins, collectively referred to as nucleoporins. The pores are about 125 million daltons

Atomic mass unit

The unified atomic mass unit or dalton is a unit that is used for indicating mass on an atomic or molecular scale. It is defined as one twelfth of the rest mass of an unbound neutral atom of carbon-12 in its nuclear and electronic ground state, and has a value of...

in molecular weight and consist of around 50 (in yeast

Yeast

Yeasts are eukaryotic micro-organisms classified in the kingdom Fungi, with 1,500 species currently described estimated to be only 1% of all fungal species. Most reproduce asexually by mitosis, and many do so by an asymmetric division process called budding...

) to 100 proteins (in vertebrate

Vertebrate

Vertebrates are animals that are members of the subphylum Vertebrata . Vertebrates are the largest group of chordates, with currently about 58,000 species described. Vertebrates include the jawless fishes, bony fishes, sharks and rays, amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and birds...

s). The pores are 100 nm in total diameter; however, the gap through which molecules freely diffuse is only about 9 nm wide, due to the presence of regulatory systems within the center of the pore. This size allows the not-free passage of small water-soluble molecules while preventing larger molecules, such as nucleic acid

Nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are biological molecules essential for life, and include DNA and RNA . Together with proteins, nucleic acids make up the most important macromolecules; each is found in abundance in all living things, where they function in encoding, transmitting and expressing genetic information...

s and larger proteins, from inappropriately entering or exiting the nucleus. These large molecules must be actively transported into the nucleus instead. The nucleus of a typical mammalian cell will have about 3000 to 4000 pores throughout its envelope, each of which contains a donut-shaped, eightfold-symmetric ring-shaped structure at a position where the inner and outer membranes fuse. Attached to the ring is a structure called the nuclear basket that extends into the nucleoplasm, and a series of filamentous extensions that reach into the cytoplasm. Both structures serve to mediate binding to nuclear transport proteins.

Most proteins, ribosomal subunits, and some DNAs are transported through the pore complexes in a process mediated by a family of transport factors known as karyopherin

Karyopherin

Karyopherins are a group of proteins involved in transporting molecules from the cytoplasm into the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. The inside of the nucleus is called the karyoplasm . Generally, karyopherin-mediated transport occurs through the nuclear pore, which acts as a gateway into and out of...

s. Those karyopherins that mediate movement into the nucleus are also called importins, whereas those that mediate movement out of the nucleus are called exportins. Most karyopherins interact directly with their cargo, although some use adaptor proteins. Steroid hormone

Steroid hormone

A steroid hormone is a steroid that acts as a hormone. Steroid hormones can be grouped into five groups by the receptors to which they bind: glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids, androgens, estrogens, and progestogens...

s such as cortisol

Cortisol

Cortisol is a steroid hormone, more specifically a glucocorticoid, produced by the adrenal gland. It is released in response to stress and a low level of blood glucocorticoids. Its primary functions are to increase blood sugar through gluconeogenesis; suppress the immune system; and aid in fat,...

and aldosterone

Aldosterone

Aldosterone is a hormone that increases the reabsorption of sodium ions and water and the release of potassium in the collecting ducts and distal convoluted tubule of the kidneys' functional unit, the nephron. This increases blood volume and, therefore, increases blood pressure. Drugs that...

, as well as other small lipid-soluble molecules involved in intercellular signaling

Cell signaling

Cell signaling is part of a complex system of communication that governs basic cellular activities and coordinates cell actions. The ability of cells to perceive and correctly respond to their microenvironment is the basis of development, tissue repair, and immunity as well as normal tissue...

, can diffuse through the cell membrane and into the cytoplasm, where they bind nuclear receptor

Nuclear receptor

In the field of molecular biology, nuclear receptors are a class of proteins found within cells that are responsible for sensing steroid and thyroid hormones and certain other molecules...

proteins that are trafficked into the nucleus. There they serve as transcription factor

Transcription factor

In molecular biology and genetics, a transcription factor is a protein that binds to specific DNA sequences, thereby controlling the flow of genetic information from DNA to mRNA...

s when bound to their ligand

Ligand (biochemistry)

In biochemistry and pharmacology, a ligand is a substance that forms a complex with a biomolecule to serve a biological purpose. In a narrower sense, it is a signal triggering molecule, binding to a site on a target protein.The binding occurs by intermolecular forces, such as ionic bonds, hydrogen...

; in the absence of ligand, many such receptors function as histone deacetylase

Histone deacetylase

Histone deacetylases are a class of enzymes that remove acetyl groups from an ε-N-acetyl lysine amino acid on a histone. This is important because DNA is wrapped around histones, and DNA expression is regulated by acetylation and de-acetylation. Its action is opposite to that of histone...

s that repress gene expression.

Nuclear lamina

In animal cells, two networks of intermediate filaments provide the nucleus with mechanical support: The nuclear laminaNuclear lamina

The nuclear lamina is a dense fibrillar network inside the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell. It is composed of intermediate filaments and membrane associated proteins. Besides providing mechanical support, the nuclear lamina regulates important cellular events such as DNA replication and cell division...

forms an organized meshwork on the internal face of the envelope, while less organized support is provided on the cytosolic face of the envelope. Both systems provide structural support for the nuclear envelope and anchoring sites for chromosomes and nuclear pores.

The nuclear lamina is composed mostly of lamin

Lamin

Nuclear lamins, also known as Class V intermediate filaments, are fibrous proteins providing structural function and transcriptional regulation in the cell nucleus. Nuclear lamins interact with membrane-associated proteins to form the nuclear lamina on the interior of the nuclear envelope...

proteins. Like all proteins, lamins are synthesized in the cytoplasm and later transported into the nucleus interior, where they are assembled before being incorporated into the existing network of nuclear lamina. Lamins found on the cytosolic face of the membrane, such as emerin

Emerin

Emerin, together with MAN1, is a LEM domain-containing integral membrane protein of the nuclear membrane in vertebrates. The function of MAN1 is not extensively known, but emerin is known to interact with nuclear lamins, barrier-to-autointegration factor , nesprin-1α, and a transcription...

and nesprin

Nesprin

The Nesprins are a family of proteins that are found primarily in the outer nuclear membrane. Nesprin-1 and -2 bind to the actin filaments. Nesprin-3 binds to plectin, which is bound to the intermediate filaments, while nesprin-4 interacts with kinesin-1....

, bind to the cytoskeleton to provide structural support. Lamins are also found inside the nucleoplasm where they form another regular structure, known as the nucleoplasmic veil, that is visible using fluorescence microscopy. The actual function of the veil is not clear, although it is excluded from the nucleolus

Nucleolus

The nucleolus is a non-membrane bound structure composed of proteins and nucleic acids found within the nucleus. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed and assembled within the nucleolus...

and is present during interphase

Interphase

Interphase is the phase of the cell cycle in which the cell spends the majority of its time and performs the majority of its purposes including preparation for cell division. In preparation for cell division, it increases its size and makes a copy of its DNA...

. Lamin structures that make up the veil, such as LEM3

LEM domain-containing protein 3

LEM domain-containing protein 3 is a membrane protein associated with laminopathies.It is also associated with osteopoikilosis.LEMD3 protein, also known as MAN1, is an inner nuclear membrane protein that was isolated from the serum of a patient with an autoimmune disease...

, bind chromatin

Chromatin

Chromatin is the combination of DNA and proteins that make up the contents of the nucleus of a cell. The primary functions of chromatin are; to package DNA into a smaller volume to fit in the cell, to strengthen the DNA to allow mitosis and meiosis and prevent DNA damage, and to control gene...

and disrupting their structure inhibits transcription of protein-coding genes.

Like the components of other intermediate filament

Intermediate filament

Intermediate filaments are a family of related proteins that share common structural and sequence features. Intermediate filaments have an average diameter of 10 nanometers, which is between that of 7 nm actin , and that of 25 nm microtubules, although they were initially designated...

s, the lamin monomer

Monomer

A monomer is an atom or a small molecule that may bind chemically to other monomers to form a polymer; the term "monomeric protein" may also be used to describe one of the proteins making up a multiprotein complex...

contains an alpha-helical domain used by two monomers to coil around each other, forming a dimer

Protein dimer

In biochemistry, a dimer is a macromolecular complex formed by two, usually non-covalently bound, macromolecules like proteins or nucleic acids...

structure called a coiled coil

Coiled coil

A coiled coil is a structural motif in proteins, in which 2-7 alpha-helices are coiled together like the strands of a rope . Many coiled coil type proteins are involved in important biological functions such as the regulation of gene expression e.g. transcription factors...

. Two of these dimer structures then join side by side, in an antiparallel

Antiparallel (biochemistry)

In biochemistry, two molecules are antiparallel if they run side-by-side in opposite directions or when both strands are complimentary to each other....

arrangement, to form a tetramer called a protofilament. Eight of these protofilaments form a lateral arrangement that is twisted to form a ropelike filament. These filaments can be assembled or disassembled in a dynamic manner, meaning that changes in the length of the filament depend on the competing rates of filament addition and removal.

Mutations in lamin genes leading to defects in filament assembly are known as laminopathies. The most notable laminopathy is the family of diseases known as progeria

Progeria

Progeria is an extremely rare genetic condition wherein symptoms resembling aspects of aging are manifested at an early age. The word progeria comes from the Greek words "pro" , meaning "before", and "géras" , meaning "old age"...

, which causes the appearance of premature aging in its sufferers. The exact mechanism by which the associated biochemical changes give rise to the aged phenotype

Phenotype

A phenotype is an organism's observable characteristics or traits: such as its morphology, development, biochemical or physiological properties, behavior, and products of behavior...

is not well understood.

Chromosomes

DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid is a nucleic acid that contains the genetic instructions used in the development and functioning of all known living organisms . The DNA segments that carry this genetic information are called genes, but other DNA sequences have structural purposes, or are involved in...

molecules organized into structures called chromosome

Chromosome

A chromosome is an organized structure of DNA and protein found in cells. It is a single piece of coiled DNA containing many genes, regulatory elements and other nucleotide sequences. Chromosomes also contain DNA-bound proteins, which serve to package the DNA and control its functions.Chromosomes...

s. Each human cell contains 2m of DNA. During most of the cell cycle

Cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that takes place in a cell leading to its division and duplication . In cells without a nucleus , the cell cycle occurs via a process termed binary fission...

these are organized in a DNA-protein complex known as chromatin

Chromatin

Chromatin is the combination of DNA and proteins that make up the contents of the nucleus of a cell. The primary functions of chromatin are; to package DNA into a smaller volume to fit in the cell, to strengthen the DNA to allow mitosis and meiosis and prevent DNA damage, and to control gene...

, and during cell division the chromatin can be seen to form the well-defined chromosome

Chromosome

A chromosome is an organized structure of DNA and protein found in cells. It is a single piece of coiled DNA containing many genes, regulatory elements and other nucleotide sequences. Chromosomes also contain DNA-bound proteins, which serve to package the DNA and control its functions.Chromosomes...

s familiar from a karyotype

Karyotype

A karyotype is the number and appearance of chromosomes in the nucleus of an eukaryotic cell. The term is also used for the complete set of chromosomes in a species, or an individual organism.p28...

. A small fraction of the cell's genes are located instead in the mitochondria.

There are two types of chromatin. Euchromatin

Euchromatin

Euchromatin is a lightly packed form of chromatin that is rich in gene concentration, and is often under active transcription. Unlike heterochromatin, it is found in both cells with nuclei and cells without nuclei...

is the less compact DNA form, and contains genes that are frequently expressed

Gene expression

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product. These products are often proteins, but in non-protein coding genes such as ribosomal RNA , transfer RNA or small nuclear RNA genes, the product is a functional RNA...

by the cell. The other type, heterochromatin

Heterochromatin

Heterochromatin is a tightly packed form of DNA, which comes in different varieties. These varieties lie on a continuum between the two extremes of constitutive and facultative heterochromatin...

, is the more compact form, and contains DNA that are infrequently transcribed. This structure is further categorized into facultative heterochromatin, consisting of genes that are organized as heterochromatin only in certain cell types or at certain stages of development, and constitutive heterochromatin that consists of chromosome structural components such as telomere

Telomere

A telomere is a region of repetitive DNA sequences at the end of a chromosome, which protects the end of the chromosome from deterioration or from fusion with neighboring chromosomes. Its name is derived from the Greek nouns telos "end" and merοs "part"...

s and centromere

Centromere

A centromere is a region of DNA typically found near the middle of a chromosome where two identical sister chromatids come closest in contact. It is involved in cell division as the point of mitotic spindle attachment...

s. During interphase the chromatin organizes itself into discrete individual patches, called chromosome territories. Active genes, which are generally found in the euchromatic region of the chromosome, tend to be located towards the chromosome's territory boundary.

Antibodies to certain types of chromatin organization, in particular, nucleosome

Nucleosome

Nucleosomes are the basic unit of DNA packaging in eukaryotes, consisting of a segment of DNA wound around a histone protein core. This structure is often compared to thread wrapped around a spool....

s, have been associated with a number of autoimmune disease

Autoimmune disease

Autoimmune diseases arise from an overactive immune response of the body against substances and tissues normally present in the body. In other words, the body actually attacks its own cells. The immune system mistakes some part of the body as a pathogen and attacks it. This may be restricted to...

s, such as systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus , often abbreviated to SLE or lupus, is a systemic autoimmune disease that can affect any part of the body. As occurs in other autoimmune diseases, the immune system attacks the body's cells and tissue, resulting in inflammation and tissue damage...

. These are known as anti-nuclear antibodies

Anti-nuclear antibody

Anti-nuclear antibodies are autoantibodies directed against contents of the cell nucleus....

(ANA) and have also been observed in concert with multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis is an inflammatory disease in which the fatty myelin sheaths around the axons of the brain and spinal cord are damaged, leading to demyelination and scarring as well as a broad spectrum of signs and symptoms...

as part of general immune system dysfunction. As in the case of progeria, the role played by the antibodies in inducing the symptoms of autoimmune diseases is not obvious.

Nucleolus

Nucleolus

The nucleolus is a non-membrane bound structure composed of proteins and nucleic acids found within the nucleus. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed and assembled within the nucleolus...

is a discrete densely stained structure found in the nucleus. It is not surrounded by a membrane, and is sometimes called a suborganelle. It forms around tandem

Tandem

Tandem is an arrangement where a team of machines, animals or people are lined up one behind another, all facing in the same direction....

repeats of rDNA, DNA coding for ribosomal RNA

Ribosomal RNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid is the RNA component of the ribosome, the enzyme that is the site of protein synthesis in all living cells. Ribosomal RNA provides a mechanism for decoding mRNA into amino acids and interacts with tRNAs during translation by providing peptidyl transferase activity...

(rRNA). These regions are called nucleolar organizer regions (NOR). The main roles of the nucleolus are to synthesize rRNA and assemble ribosomes. The structural cohesion of the nucleolus depends on its activity, as ribosomal assembly in the nucleolus results in the transient association of nucleolar components, facilitating further ribosomal assembly, and hence further association. This model is supported by observations that inactivation of rDNA results in intermingling of nucleolar structures.

In the first step of ribosome assembly, a protein called RNA polymerase I

RNA polymerase I

RNA polymerase I is, in eukaryotes, the enzyme that only transcribes ribosomal RNA , a type of RNA that accounts for over 50% of the total RNA synthesized in a cell....

transcribes rDNA, which forms a large pre-rRNA precursor. This is cleaved into the subunits 5.8S, 18S, and 28S rRNA. The transcription, post-transcriptional processing, and assembly of rRNA occurs in the nucleolus, aided by small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) molecules, some of which are derived from spliced intron

Intron

An intron is any nucleotide sequence within a gene that is removed by RNA splicing to generate the final mature RNA product of a gene. The term intron refers to both the DNA sequence within a gene, and the corresponding sequence in RNA transcripts. Sequences that are joined together in the final...

s from messenger RNA

Messenger RNA

Messenger RNA is a molecule of RNA encoding a chemical "blueprint" for a protein product. mRNA is transcribed from a DNA template, and carries coding information to the sites of protein synthesis: the ribosomes. Here, the nucleic acid polymer is translated into a polymer of amino acids: a protein...

s encoding genes related to ribosomal function. The assembled ribosomal subunits are the largest structures passed through the nuclear pores.

When observed under the electron microscope

Electron microscope

An electron microscope is a type of microscope that uses a beam of electrons to illuminate the specimen and produce a magnified image. Electron microscopes have a greater resolving power than a light-powered optical microscope, because electrons have wavelengths about 100,000 times shorter than...

, the nucleolus can be seen to consist of three distinguishable regions: the innermost fibrillar centers (FCs), surrounded by the dense fibrillar component (DFC), which in turn is bordered by the granular component (GC). Transcription of the rDNA occurs either in the FC or at the FC-DFC boundary, and, therefore, when rDNA transcription in the cell is increased, more FCs are detected. Most of the cleavage and modification of rRNAs occurs in the DFC, while the latter steps involving protein assembly onto the ribosomal subunits occur in the GC.

Other subnuclear bodies

| Structure name | Structure diameter | |

|---|---|---|

| Cajal bodies | 0.2–2.0 µm | |

| PIKA | 5 µm | |

| PML bodies | 0.2–1.0 µm | |

| Paraspeckles | 0.2–1.0 µm | |

| Speckles | 20–25 nm |

Besides the nucleolus, the nucleus contains a number of other non-membrane-delineated bodies. These include Cajal bodies, Gemini of coiled bodies, polymorphic interphase karyosomal association (PIKA), promyelocytic leukaemia (PML) bodies, paraspeckle

Paraspeckle

In anatomy, a paraspeckle is an irregularly shaped sub-cellular compartment, approximately 0.2-1 μm in size, found in the nucleus' interchromatin space. First documented in HeLa cells, where there are generally 10-30 per nucleus, paraspeckles are now known to also exist in all human primary cells,...

s, and splicing speckles. Although little is known about a number of these domains, they are significant in that they show that the nucleoplasm is not uniform mixture, but rather contains organized functional subdomains.

Other subnuclear structures appear as part of abnormal disease processes. For example, the presence of small intranuclear rods has been reported in some cases of nemaline myopathy

Nemaline myopathy

Nemaline myopathy is a congenital, hereditary neuromuscular disorder that causes muscle weakness, generally nonprogressive, of varying severity....

. This condition typically results from mutations in actin

Actin

Actin is a globular, roughly 42-kDa moonlighting protein found in all eukaryotic cells where it may be present at concentrations of over 100 μM. It is also one of the most highly-conserved proteins, differing by no more than 20% in species as diverse as algae and humans...

, and the rods themselves consist of mutant actin as well as other cytoskeletal proteins.

Cajal bodies and gems

A nucleus typically contains between 1 and 10 compact structures called Cajal bodiesCajal body

Cajal bodies are spherical sub-organelles of 0.3-1.0 µm in diameter found in the nucleus of proliferative cells like embryonic cells and tumor cells, or metabolically active cells like neurons. In contrast to cytoplasmic organelles, CBs lack any phospholipid membrane which would separate their...

or coiled bodies (CB), whose diameter measures between 0.2 µm and 2.0 µm depending on the cell type and species. When seen under an electron microscope

Electron microscope

An electron microscope is a type of microscope that uses a beam of electrons to illuminate the specimen and produce a magnified image. Electron microscopes have a greater resolving power than a light-powered optical microscope, because electrons have wavelengths about 100,000 times shorter than...

, they resemble balls of tangled thread and are dense foci of distribution for the protein coilin

Coilin

Coilin is a protein that in humans is encoded by the COIL gene.Coilin protein is one of the main molecular components of Cajal bodies . Cajal bodies are nuclear suborganelles of varying number and composition that are involved in the post-transcriptional modification of small nuclear and small...

. CBs are involved in a number of different roles relating to RNA processing, specifically small nucleolar RNA

SnoRNA

Small nucleolar RNAs are a class of small RNA molecules that primarily guide chemical modifications of other RNAs, mainly ribosomal RNAs, transfer RNAs and small nuclear RNAs...

(snoRNA) and small nuclear RNA

Small nuclear RNA

Small nuclear ribonucleic acid is a class of small RNA molecules that are found within the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. They are transcribed by RNA polymerase II or RNA polymerase III and are involved in a variety of important processes such as RNA splicing , regulation of transcription factors ...

(snRNA) maturation, and histone mRNA modification.

Similar to Cajal bodies are Gemini of coiled bodies, or gems, whose name is derived from the Gemini constellation

Gemini (constellation)

Gemini is one of the constellations of the zodiac. It was one of the 48 constellations described by the 2nd century astronomer Ptolemy and it remains one of the 88 modern constellations today. Its name is Latin for "twins", and it is associated with the twins Castor and Pollux in Greek mythology...

in reference to their close "twin" relationship with CBs. Gems are similar in size and shape to CBs, and in fact are virtually indistinguishable under the microscope. Unlike CBs, gems do not contain small nuclear ribonucleoproteins

SnRNP

snRNPs , or small nuclear ribonucleoproteins, are RNA-protein complexes that combine with unmodified pre-mRNA and various other proteins to form a spliceosome, a large RNA-protein molecular complex upon which splicing of pre-mRNA occurs...

(snRNPs), but do contain a protein called survivor of motor neurons (SMN) whose function relates to snRNP biogenesis. Gems are believed to assist CBs in snRNP biogenesis, though it has also been suggested from microscopy evidence that CBs and gems are different manifestations of the same structure.

RAFA and PTF domains

RAFA domains, or polymorphic interphase karyosomal associations, were first described in microscopy studies in 1991. Their function was and remains unclear, though they were not thought to be associated with active DNA replication, transcription, or RNA processing. They have been found to often associate with discrete domains defined by dense localization of the transcription factorTranscription factor

In molecular biology and genetics, a transcription factor is a protein that binds to specific DNA sequences, thereby controlling the flow of genetic information from DNA to mRNA...

PTF, which promotes transcription of snRNA.

PML bodies

Promyelocytic leukaemia bodies (PML bodies) are spherical bodies found scattered throughout the nucleoplasm, measuring around 0.2–1.0 µm. They are known by a number of other names, including nuclear domain 10 (ND10), Kremer bodies, and PML oncogenic domains. They are often seen in the nucleus in association with Cajal bodies and cleavage bodies. It has been suggested that they play a role in regulating transcription.Paraspeckles

Discovered by Fox et al. in 2002, paraspeckleParaspeckle

In anatomy, a paraspeckle is an irregularly shaped sub-cellular compartment, approximately 0.2-1 μm in size, found in the nucleus' interchromatin space. First documented in HeLa cells, where there are generally 10-30 per nucleus, paraspeckles are now known to also exist in all human primary cells,...

s are irregularly shaped compartments in the nucleus' interchromatin space. First documented in HeLa cells, where there are generally 10–30 per nucleus, paraspeckles are now known to also exist in all human primary cells, transformed cell lines, and tissue sections. Their name is derived from their distribution in the nucleus; the "para" is short for parallel and the "speckles" refers to the splicing speckles to which they are always in close proximity.

Paraspeckles are dynamic structures that are altered in response to changes in cellular metabolic activity. They are transcription dependent and in the absence of RNA Pol II transcription, the paraspeckle disappears and all of its associated protein components (PSP1, p54nrb, PSP2, CFI(m)68, and PSF) form a crescent shaped perinucleolar cap in the nucleolus

Nucleolus

The nucleolus is a non-membrane bound structure composed of proteins and nucleic acids found within the nucleus. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed and assembled within the nucleolus...

. This phenomenon is demonstrated during the cell cycle. In the cell cycle

Cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that takes place in a cell leading to its division and duplication . In cells without a nucleus , the cell cycle occurs via a process termed binary fission...

, paraspeckles are present during interphase

Interphase

Interphase is the phase of the cell cycle in which the cell spends the majority of its time and performs the majority of its purposes including preparation for cell division. In preparation for cell division, it increases its size and makes a copy of its DNA...

and during all of mitosis

Mitosis

Mitosis is the process by which a eukaryotic cell separates the chromosomes in its cell nucleus into two identical sets, in two separate nuclei. It is generally followed immediately by cytokinesis, which divides the nuclei, cytoplasm, organelles and cell membrane into two cells containing roughly...

except for telophase

Telophase

Telophase from the ancient Greek "τελος" and "φασις" , is a stage in both meiosis and mitosis in a eukaryotic cell. During telophase, the effects of prophase and prometaphase events are reversed. Two daughter nuclei form in the cell. The nuclear envelopes of the daughter cells are formed from the...

. During telophase, when the two daughter nuclei are formed, there is no RNA

RNA

Ribonucleic acid , or RNA, is one of the three major macromolecules that are essential for all known forms of life....

Pol II transcription

Transcription (genetics)

Transcription is the process of creating a complementary RNA copy of a sequence of DNA. Both RNA and DNA are nucleic acids, which use base pairs of nucleotides as a complementary language that can be converted back and forth from DNA to RNA by the action of the correct enzymes...

so the protein components instead form a perinucleolar cap.

Splicing speckles

Speckles are subnuclear structures that are enriched in pre-messenger RNA splicing factors and are located in the interchromatin regions of the nucleoplasm of mammalian cells. At the fluorescence-microscope level they appear as irregular, punctate structures, which vary in size and shape, and when examined by electron microscopy they are seen as clusters of interchromatin granules. Speckles are dynamic structures, and both their protein and RNA-protein components can cycle continuously between speckles and other nuclear locations, including active transcription sites. Studies on the composition, structure and behaviour of speckles have provided a model for understanding the functional compartmentalization of the nucleus and the organization of the gene-expression machinery.Sometimes referred to as interchromatin granule clusters or as splicing-factor compartments, speckles are rich in splicing snRNPs and other splicing proteins necessary for pre-mRNA processing. Because of a cell's changing requirements, the composition and location of these bodies changes according to mRNA transcription and regulation via phosphorylation

Phosphorylation

Phosphorylation is the addition of a phosphate group to a protein or other organic molecule. Phosphorylation activates or deactivates many protein enzymes....

of specific proteins.

Function

The main function of the cell nucleus is to control gene expression and mediate the replication of DNA during the cell cycleCell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that takes place in a cell leading to its division and duplication . In cells without a nucleus , the cell cycle occurs via a process termed binary fission...

. The nucleus provides a site for genetic transcription

Transcription (genetics)

Transcription is the process of creating a complementary RNA copy of a sequence of DNA. Both RNA and DNA are nucleic acids, which use base pairs of nucleotides as a complementary language that can be converted back and forth from DNA to RNA by the action of the correct enzymes...

that is segregated from the location of translation

Translation (genetics)

In molecular biology and genetics, translation is the third stage of protein biosynthesis . In translation, messenger RNA produced by transcription is decoded by the ribosome to produce a specific amino acid chain, or polypeptide, that will later fold into an active protein...

in the cytoplasm, allowing levels of gene regulation that are not available to prokaryote

Prokaryote

The prokaryotes are a group of organisms that lack a cell nucleus , or any other membrane-bound organelles. The organisms that have a cell nucleus are called eukaryotes. Most prokaryotes are unicellular, but a few such as myxobacteria have multicellular stages in their life cycles...

s.

Cell compartmentalization

The nuclear envelope allows the nucleus to control its contents, and separate them from the rest of the cytoplasm where necessary. This is important for controlling processes on either side of the nuclear membrane. In some cases where a cytoplasmic process needs to be restricted, a key participant is removed to the nucleus, where it interacts with transcription factors to downregulate the production of certain enzymes in the pathway. This regulatory mechanism occurs in the case of glycolysisGlycolysis

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose C6H12O6, into pyruvate, CH3COCOO− + H+...

, a cellular pathway for breaking down glucose

Glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar and an important carbohydrate in biology. Cells use it as the primary source of energy and a metabolic intermediate...

to produce energy. Hexokinase

Hexokinase

A hexokinase is an enzyme that phosphorylates a six-carbon sugar, a hexose, to a hexose phosphate. In most tissues and organisms, glucose is the most important substrate of hexokinases, and glucose-6-phosphate the most important product....

is an enzyme responsible for the first the step of glycolysis, forming glucose-6-phosphate

Glucose-6-phosphate

Glucose 6-phosphate is glucose sugar phosphorylated on carbon 6. This compound is very common in cells as the vast majority of glucose entering a cell will become phosphorylated in this way....

from glucose. At high concentrations of fructose-6-phosphate, a molecule made later from glucose-6-phosphate, a regulator protein removes hexokinase to the nucleus, where it forms a transcriptional repressor complex with nuclear proteins to reduce the expression of genes involved in glycolysis.

In order to control which genes are being transcribed, the cell separates some transcription factor

Transcription factor

In molecular biology and genetics, a transcription factor is a protein that binds to specific DNA sequences, thereby controlling the flow of genetic information from DNA to mRNA...

proteins responsible for regulating gene expression from physical access to the DNA until they are activated by other signaling pathways. This prevents even low levels of inappropriate gene expression. For example, in the case of NF-κB-controlled genes, which are involved in most inflammatory

Inflammation

Inflammation is part of the complex biological response of vascular tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants. Inflammation is a protective attempt by the organism to remove the injurious stimuli and to initiate the healing process...

responses, transcription is induced in response to a signal pathway

Cell signaling

Cell signaling is part of a complex system of communication that governs basic cellular activities and coordinates cell actions. The ability of cells to perceive and correctly respond to their microenvironment is the basis of development, tissue repair, and immunity as well as normal tissue...

such as that initiated by the signaling molecule TNF-α, binds to a cell membrane receptor, resulting in the recruitment of signalling proteins, and eventually activating the transcription factor NF-κB. A nuclear localisation signal on the NF-κB protein allows it to be transported through the nuclear pore and into the nucleus, where it stimulates the transcription of the target genes.

The compartmentalization allows the cell to prevent translation of unspliced mRNA. Eukaryotic mRNA contains introns that must be removed before being translated to produce functional proteins. The splicing is done inside the nucleus before the mRNA can be accessed by ribosomes for translation. Without the nucleus, ribosomes would translate newly transcribed (unprocessed) mRNA, resulting in misformed and nonfunctional proteins.

Gene expression

Gene expression first involves transcriptionTranscription (genetics)

Transcription is the process of creating a complementary RNA copy of a sequence of DNA. Both RNA and DNA are nucleic acids, which use base pairs of nucleotides as a complementary language that can be converted back and forth from DNA to RNA by the action of the correct enzymes...

, in which DNA is used as a template to produce RNA. In the case of genes encoding proteins, that RNA produced from this process is messenger RNA

Messenger RNA

Messenger RNA is a molecule of RNA encoding a chemical "blueprint" for a protein product. mRNA is transcribed from a DNA template, and carries coding information to the sites of protein synthesis: the ribosomes. Here, the nucleic acid polymer is translated into a polymer of amino acids: a protein...

(mRNA), which then needs to be translated

Translation (genetics)

In molecular biology and genetics, translation is the third stage of protein biosynthesis . In translation, messenger RNA produced by transcription is decoded by the ribosome to produce a specific amino acid chain, or polypeptide, that will later fold into an active protein...

by ribosomes to form a protein. As ribosomes are located outside the nucleus, mRNA produced needs to be exported.

Since the nucleus is the site of transcription, it also contains a variety of proteins that either directly mediate transcription or are involved in regulating the process. These proteins include helicase

Helicase

Helicases are a class of enzymes vital to all living organisms. They are motor proteins that move directionally along a nucleic acid phosphodiester backbone, separating two annealed nucleic acid strands using energy derived from ATP hydrolysis.-Function:Many cellular processes Helicases are a...

s, which unwind the double-stranded DNA molecule to facilitate access to it, RNA polymerase

RNA polymerase

RNA polymerase is an enzyme that produces RNA. In cells, RNAP is needed for constructing RNA chains from DNA genes as templates, a process called transcription. RNA polymerase enzymes are essential to life and are found in all organisms and many viruses...

s, which synthesize the growing RNA molecule, topoisomerase

Topoisomerase

Topoisomerases are enzymes that regulate the overwinding or underwinding of DNA. The winding problem of DNA arises due to the intertwined nature of its double helical structure. For example, during DNA replication, DNA becomes overwound ahead of a replication fork...

s, which change the amount of supercoiling in DNA, helping it wind and unwind, as well as a large variety of transcription factor

Transcription factor

In molecular biology and genetics, a transcription factor is a protein that binds to specific DNA sequences, thereby controlling the flow of genetic information from DNA to mRNA...

s that regulate expression.

Processing of pre-mRNA

Newly synthesized mRNA molecules are known as primary transcriptPrimary transcript

A primary transcript is an RNA molecule that has not yet undergone any modification after its synthesis. For example, a precursor messenger RNA is a primary transcript that becomes a messenger RNA after processing, and a primary microRNA precursor becomes a microRNA after processing....

s or pre-mRNA. They must undergo post-transcriptional modification

Post-transcriptional modification

Post-transcriptional modification is a process in cell biology by which, in eukaryotic cells, primary transcript RNA is converted into mature RNA. A notable example is the conversion of precursor messenger RNA into mature messenger RNA , which includes splicing and occurs prior to protein synthesis...

in the nucleus before being exported to the cytoplasm; mRNA that appears in the cytoplasm without these modifications is degraded rather than used for protein translation

Translation (genetics)

In molecular biology and genetics, translation is the third stage of protein biosynthesis . In translation, messenger RNA produced by transcription is decoded by the ribosome to produce a specific amino acid chain, or polypeptide, that will later fold into an active protein...

. The three main modifications are 5' cap

5' cap

The 5' cap is a specially altered nucleotide on the 5' end of precursor messenger RNA and some other primary RNA transcripts as found in eukaryotes. The process of 5' capping is vital to creating mature messenger RNA, which is then able to undergo translation...

ping, 3' polyadenylation

Polyadenylation

Polyadenylation is the addition of a poly tail to an RNA molecule. The poly tail consists of multiple adenosine monophosphates; in other words, it is a stretch of RNA that has only adenine bases. In eukaryotes, polyadenylation is part of the process that produces mature messenger RNA for translation...

, and RNA splicing

RNA splicing

In molecular biology and genetics, splicing is a modification of an RNA after transcription, in which introns are removed and exons are joined. This is needed for the typical eukaryotic messenger RNA before it can be used to produce a correct protein through translation...

. While in the nucleus, pre-mRNA is associated with a variety of proteins in complexes known as heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein particle

Heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein particle

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins are complexes of RNA and protein present in the cell nucleus during gene transcription and subsequent post-transcriptional modification of the newly synthesized RNA . The presence of the proteins bound to a pre-mRNA molecule serves as a signal that the...

s (hnRNPs). Addition of the 5' cap occurs co-transcriptionally and is the first step in post-transcriptional modification. The 3' poly-adenine

Adenine

Adenine is a nucleobase with a variety of roles in biochemistry including cellular respiration, in the form of both the energy-rich adenosine triphosphate and the cofactors nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and flavin adenine dinucleotide , and protein synthesis, as a chemical component of DNA...

tail is only added after transcription is complete.

RNA splicing, carried out by a complex called the spliceosome

Spliceosome

A spliceosome is a complex of snRNA and protein subunits that removes introns from a transcribed pre-mRNA segment. This process is generally referred to as splicing.-Composition:...

, is the process by which introns, or regions of DNA that do not code for protein, are removed from the pre-mRNA and the remaining exon

Exon

An exon is a nucleic acid sequence that is represented in the mature form of an RNA molecule either after portions of a precursor RNA have been removed by cis-splicing or when two or more precursor RNA molecules have been ligated by trans-splicing. The mature RNA molecule can be a messenger RNA...

s connected to re-form a single continuous molecule. This process normally occurs after 5' capping and 3' polyadenylation but can begin before synthesis is complete in transcripts with many exons. Many pre-mRNAs, including those encoding antibodies

Antibody

An antibody, also known as an immunoglobulin, is a large Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique part of the foreign target, termed an antigen...

, can be spliced in multiple ways to produce different mature mRNAs that encode different protein sequences

Primary structure

The primary structure of peptides and proteins refers to the linear sequence of its amino acid structural units. The term "primary structure" was first coined by Linderstrøm-Lang in 1951...

. This process is known as alternative splicing

Alternative splicing

Alternative splicing is a process by which the exons of the RNA produced by transcription of a gene are reconnected in multiple ways during RNA splicing...

, and allows production of a large variety of proteins from a limited amount of DNA.

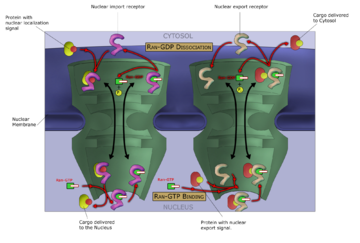

Nuclear transport

Karyopherin

Karyopherins are a group of proteins involved in transporting molecules from the cytoplasm into the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. The inside of the nucleus is called the karyoplasm . Generally, karyopherin-mediated transport occurs through the nuclear pore, which acts as a gateway into and out of...

s called importin

Importin

Importin is a type of protein that moves other protein molecules into the nucleus by binding to a specific recognition sequence, called the nuclear localization signal . Importin is classified as a karyopherin....

s to enter the nucleus and exportins to exit. "Cargo" proteins that must be translocated from the cytoplasm to the nucleus contain short amino acid sequences known as nuclear localization signal

Nuclear localization signal

A nuclear localization signal or sequence is an amino acid sequence which 'tags' a protein for import into the cell nucleus by nuclear transport. Typically, this signal consists of one or more short sequences of positively charged lysines or arginines exposed on the protein surface. Different...

s, which are bound by importins, while those transported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm carry nuclear export signal

Nuclear export signal

A nuclear export signal is a short amino acid sequence of 4 hydrophobic residues in a protein that targets it for export from the cell nucleus to the cytoplasm through the nuclear pore complex using nuclear transport. It has the opposite effect of a nuclear localization signal, which targets a...

s bound by exportins. The ability of importins and exportins to transport their cargo is regulated by GTPase

GTPase

GTPases are a large family of hydrolase enzymes that can bind and hydrolyze guanosine triphosphate . The GTP binding and hydrolysis takes place in the highly conserved G domain common to all GTPases.-Functions:...

s, enzymes that hydrolyze the molecule guanosine triphosphate

Guanosine triphosphate

Guanosine-5'-triphosphate is a purine nucleoside triphosphate. It can act as a substrate for the synthesis of RNA during the transcription process...

to release energy. The key GTPase in nuclear transport is Ran

Ran (biology)

Ran is a small 25Kda protein that is involved in transport into and out of the cell nucleus during interphase and also involved in mitosis. It is a member of the Ras superfamily....

, which can bind either GTP or GDP (guanosine diphosphate), depending on whether it is located in the nucleus or the cytoplasm. Whereas importins depend on RanGTP to dissociate from their cargo, exportins require RanGTP in order to bind to their cargo.

Nuclear import depends on the importin binding its cargo in the cytoplasm and carrying it through the nuclear pore into the nucleus. Inside the nucleus, RanGTP acts to separate the cargo from the importin, allowing the importin to exit the nucleus and be reused. Nuclear export is similar, as the exportin binds the cargo inside the nucleus in a process facilitated by RanGTP, exits through the nuclear pore, and separates from its cargo in the cytoplasm.

Specialized export proteins exist for translocation of mature mRNA and tRNA to the cytoplasm after post-transcriptional modification is complete. This quality-control mechanism is important due to the these molecules' central role in protein translation; mis-expression of a protein due to incomplete excision of exons or mis-incorporation of amino acids could have negative consequences for the cell; thus, incompletely modified RNA that reaches the cytoplasm is degraded rather than used in translation.

Assembly and disassembly

During its lifetime, a nucleus may be broken down, either in the process of cell divisionCell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell divides into two or more daughter cells . Cell division is usually a small segment of a larger cell cycle. This type of cell division in eukaryotes is known as mitosis, and leaves the daughter cell capable of dividing again. The corresponding sort...

or as a consequence of apoptosis

Apoptosis

Apoptosis is the process of programmed cell death that may occur in multicellular organisms. Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes and death. These changes include blebbing, cell shrinkage, nuclear fragmentation, chromatin condensation, and chromosomal DNA fragmentation...

, a regulated form of cell death. During these events, the structural components of the nucleus — the envelope and lamina — can be systematically degraded.

In most cells, the disassembly of the nuclear envelope marks the end of the prophase

Prophase

Prophase, from the ancient Greek πρό and φάσις , is a stage of mitosis in which the chromatin condenses into a highly ordered structure called a chromosome in which the chromatin becomes visible. This process, called chromatin condensation, is mediated by the condensin complex...

of mitosis

Mitosis

Mitosis is the process by which a eukaryotic cell separates the chromosomes in its cell nucleus into two identical sets, in two separate nuclei. It is generally followed immediately by cytokinesis, which divides the nuclei, cytoplasm, organelles and cell membrane into two cells containing roughly...

. However, this disassembly of the nucleus is not a universal feature of mitosis and does not occur in all cells. Some unicellular eukaryotes (e.g., yeasts) undergo so-called closed mitosis, in which the nuclear envelope remains intact. In closed mitosis, the daughter chromosomes migrate to opposite poles of the nucleus, which then divides in two. The cells of higher eukaryotes, however, usually undergo open mitosis, which is characterized by breakdown of the nuclear envelope. The daughter chromosomes then migrate to opposite poles of the mitotic spindle, and new nuclei reassemble around them

At a certain point during the cell cycle

Cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that takes place in a cell leading to its division and duplication . In cells without a nucleus , the cell cycle occurs via a process termed binary fission...

in open mitosis, the cell divides to form two cells. In order for this process to be possible, each of the new daughter cells must have a full set of genes, a process requiring replication of the chromosomes as well as segregation of the separate sets. This occurs by the replicated chromosomes, the sister chromatids, attaching to microtubule

Microtubule

Microtubules are a component of the cytoskeleton. These rope-like polymers of tubulin can grow as long as 25 micrometers and are highly dynamic. The outer diameter of microtubule is about 25 nm. Microtubules are important for maintaining cell structure, providing platforms for intracellular...

s, which in turn are attached to different centrosome

Centrosome

In cell biology, the centrosome is an organelle that serves as the main microtubule organizing center of the animal cell as well as a regulator of cell-cycle progression. It was discovered by Edouard Van Beneden in 1883...

s. The sister chromatids can then be pulled to separate locations in the cell. In many cells, the centrosome is located in the cytoplasm, outside the nucleus; the microtubules would be unable to attach to the chromatids in the presence of the nuclear envelope. Therefore the early stages in the cell cycle, beginning in prophase

Prophase

Prophase, from the ancient Greek πρό and φάσις , is a stage of mitosis in which the chromatin condenses into a highly ordered structure called a chromosome in which the chromatin becomes visible. This process, called chromatin condensation, is mediated by the condensin complex...

and until around prometaphase

Prometaphase

Prometaphase is the phase of mitosis following prophase and preceding metaphase, in eukaryotic somatic cells. In Prometaphase, The nuclear envelope breaks into fragments and disappears. The tiny nucleolus inside the nuclear envolope, also dissolves. Microtubules emerging from the centrosomes at the...

, the nuclear membrane is dismantled. Likewise, during the same period, the nuclear lamina is also disassembled, a process regulated by phosphorylation of the lamins by protein kinases such as the CDC2 protein kinase. Towards the end of the cell cycle, the nuclear membrane is reformed, and around the same time, the nuclear lamina are reassembled by dephosphorylating the lamins.

However, in dinoflagellates, the nuclear envelope remains intact, the centrosomes are located in the cytoplasm, and the microtubules come in contact with chromosomes, whose centromeric regions are incorporated into the nuclear envelope (the so-called closed mitosis with extranuclear spindle). In many other protists (e.g., ciliate

Ciliate

The ciliates are a group of protozoans characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to flagella but typically shorter and present in much larger numbers with a different undulating pattern than flagella...

s, sporozoans

Apicomplexa

The Apicomplexa are a large group of protists, most of which possess a unique organelle called apicoplast and an apical complex structure involved in penetrating a host's cell. They are unicellular, spore-forming, and exclusively parasites of animals. Motile structures such as flagella or...

) and fungi, the centrosomes are intranuclear, and their nuclear envelope also does not disassemle during cell division.

Apoptosis

Apoptosis

Apoptosis is the process of programmed cell death that may occur in multicellular organisms. Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes and death. These changes include blebbing, cell shrinkage, nuclear fragmentation, chromatin condensation, and chromosomal DNA fragmentation...

is a controlled process in which the cell's structural components are destroyed, resulting in death of the cell. Changes associated with apoptosis directly affect the nucleus and its contents, for example, in the condensation of chromatin and the disintegration of the nuclear envelope and lamina. The destruction of the lamin networks is controlled by specialized apoptotic protease

Protease

A protease is any enzyme that conducts proteolysis, that is, begins protein catabolism by hydrolysis of the peptide bonds that link amino acids together in the polypeptide chain forming the protein....

s called caspase

Caspase

Caspases, or cysteine-aspartic proteases or cysteine-dependent aspartate-directed proteases are a family of cysteine proteases that play essential roles in apoptosis , necrosis, and inflammation....

s, which cleave the lamin proteins and, thus, degrade the nucleus' structural integrity. Lamin cleavage is sometimes used as a laboratory indicator of caspase activity in assay

Assay

An assay is a procedure in molecular biology for testing or measuring the activity of a drug or biochemical in an organism or organic sample. A quantitative assay may also measure the amount of a substance in a sample. Bioassays and immunoassays are among the many varieties of specialized...

s for early apoptotic activity. Cells that express mutant caspase-resistant lamins are deficient in nuclear changes related to apoptosis, suggesting that lamins play a role in initiating the events that lead to apoptotic degradation of the nucleus. Inhibition of lamin assembly itself is an inducer of apoptosis.

The nuclear envelope acts as a barrier that prevents both DNA and RNA viruses from entering the nucleus. Some viruses require access to proteins inside the nucleus in order to replicate and/or assemble. DNA viruses, such as herpesvirus replicate and assemble in the cell nucleus, and exit by budding through the inner nuclear membrane. This process is accompanied by disassembly of the lamina on the nuclear face of the inner membrane.

Anucleated and polynucleated cells

Red blood cell

Red blood cells are the most common type of blood cell and the vertebrate organism's principal means of delivering oxygen to the body tissues via the blood flow through the circulatory system...

s, or a result of faulty cell division.

Anucleated cells contain no nucleus and are, therefore, incapable of dividing to produce daughter cells. The best-known anucleated cell is the mammalian red blood cell, or erythrocyte, which also lacks other organelles such as mitochondria, and serves primarily as a transport vessel to ferry oxygen

Oxygen

Oxygen is the element with atomic number 8 and represented by the symbol O. Its name derives from the Greek roots ὀξύς and -γενής , because at the time of naming, it was mistakenly thought that all acids required oxygen in their composition...

from the lungs to the body's tissues. Erythrocytes mature through erythropoiesis

Erythropoiesis

Erythropoiesis is the process by which red blood cells are produced. It is stimulated by decreased O2 in circulation, which is detected by the kidneys, which then secrete the hormone erythropoietin...

in the bone marrow

Bone marrow

Bone marrow is the flexible tissue found in the interior of bones. In humans, bone marrow in large bones produces new blood cells. On average, bone marrow constitutes 4% of the total body mass of humans; in adults weighing 65 kg , bone marrow accounts for approximately 2.6 kg...

, where they lose their nuclei, organelles, and ribosomes. The nucleus is expelled during the process of differentiation from an erythroblast to a reticulocyte

Reticulocyte

Reticulocytes are immature red blood cells, typically composing about 1% of the red cells in the human body.Reticulocytes develop and mature in the red bone marrow and then circulate for about a day in the blood stream before developing into mature red blood cells. Like mature red blood cells,...

, which is the immediate precursor of the mature erythrocyte. The presence of mutagen

Mutagen

In genetics, a mutagen is a physical or chemical agent that changes the genetic material, usually DNA, of an organism and thus increases the frequency of mutations above the natural background level. As many mutations cause cancer, mutagens are therefore also likely to be carcinogens...

s may induce the release of some immature "micronucleated" erythrocytes into the bloodstream. Anucleated cells can also arise from flawed cell division in which one daughter lacks a nucleus and the other has two nuclei.

Polynucleated cells contain multiple nuclei. Most Acantharea

Acantharea

The Acantharea are a group of radiolarian protozoa, distinguished mainly by their skeletons.-Structure:These are composed of strontium sulfate crystals, which do not fossilize, and take the form of either ten diametric or twenty radial spines...

n species of protozoa

Protozoa