.gif)

Immunity (medical)

Encyclopedia

Immunity is a biological term that describes a state of having sufficient biological defenses to avoid infection

, disease

, or other unwanted biological invasion. Immunity involves both specific and non-specific components. The non-specific components act either as barriers or as eliminators of wide range of pathogens irrespective of antigenic specificity. Other components of the immune system

adapt themselves to each new disease encountered and are able to generate pathogen-specific immunity.

Innate immunity, or nonspecific, immunity is the natural resistance with which a person is born. It provides resistance through several physical, chemical, and cellular approaches. Microbes first encounter the epithelial layers, physical barriers that line our skin and mucous membranes. Subsequent general defenses include secreted chemical signals (cytokines), antimicrobial substances, fever, and phagocytic activity associated with the inflammatory response. The phagocytes express cell surface receptors that can bind and respond to common molecular patterns expressed on the surface of invading microbes. Through these approaches, innate immunity can prevent the colonization, entry, and spread of microbes.

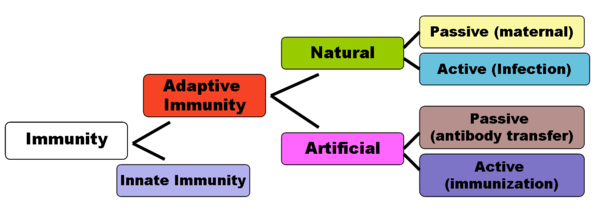

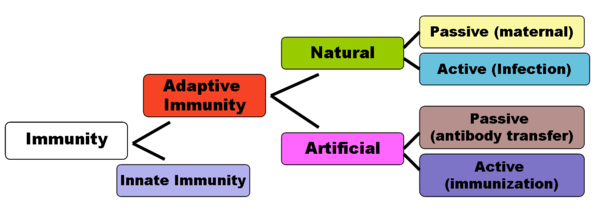

Adaptive immunity is often sub-divided into two major types depending on how the immunity was introduced. Naturally acquired immunity occurs through contact with a disease causing agent, when the contact was not deliberate, whereas artificially acquired immunity develops only through deliberate actions

such as vaccination. Both naturally and artificially acquired immunity can be further subdivided depending on whether immunity is induced in the host or passively transferred from a immune host. Passive immunity is acquired through transfer of antibodies or activated T-cells from an immune host, and is short lived -- usually lasting only a few months -- whereas active immunity is induced in the host itself by antigen, and lasts much longer, sometimes life-long. The diagram below summarizes these divisions of immunity.

A further subdivision of adaptive immunity is characterized by the cells involved; humoral immunity

A further subdivision of adaptive immunity is characterized by the cells involved; humoral immunity

is the aspect of immunity that is mediated by secreted antibodies, whereas the protection provided by cell mediated immunity involves T-lymphocytes alone. Humoral immunity is active when the organism generates its own antibodies, and passive when antibodies are transferred between individuals. Similarly, cell mediated immunity is active when the organisms’ own T-cells are stimulated and passive when T cells come from another organism.

The concept of immunity has intrigued mankind for thousands of years. The prehistoric view of disease was that it was caused by supernatural forces, and that illness was a form of theurgic

The concept of immunity has intrigued mankind for thousands of years. The prehistoric view of disease was that it was caused by supernatural forces, and that illness was a form of theurgic

punishment for “bad deeds” or “evil thoughts” visited upon the soul by the gods or by one’s enemies. Between the time of Hippocrates

and the 19th century, when the foundations of the scientific method were laid, diseases were attributed to an alteration or imbalance in one of the four humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile or black bile). Also popular during this time was the miasma theory

, which held that diseases such as cholera

or the Black Plague were caused by a miasma, a noxious form of "bad air". If someone were exposed to the miasma, they could get the disease.

The modern word “immunity” derives from the Latin

immunis, meaning exemption from military service, tax payments or other public services. The first written descriptions of the concept of immunity may have been made by the Athenian Thucydides

who, in 430 BC, described that when the plague hit Athens

“the sick and the dying were tended by the pitying care of those who had recovered, because they knew the course of the disease and were themselves free from apprehensions. For no one was ever attacked a second time, or not with a fatal result”. The term “immunes”, is also found in the epic poem “Pharsalia

” written around 60 B.C. by the poet Marcus Annaeus Lucanus

to describe a North African tribe’s resistance to snake venom

.

The first clinical description of immunity which arose from a specific disease causing organism is probably Kitab fi al-jadari wa-al-hasbah (A Treatise on Smallpox and Measles, translated 1848) written by the Islamic physician Al-Razi

in the 9th century. In the treatise, Al Razi describes the clinical presentation of smallpox and measles and goes on to indicate that that exposure to these specific agents confers lasting immunity (although he does not use this term). However, it was with Louis Pasteur

’s Germ theory of disease

that the fledgling science of immunology

began to explain how bacteria caused disease, and how, following infection, the human body gained the ability to resist further infections.

The birth of active immunotherapy may have begun with Mithridates VI of Pontus

The birth of active immunotherapy may have begun with Mithridates VI of Pontus

. To induce active immunity for snake venom, he recommended using a method similar to modern toxoid

serum therapy, by drinking the blood of animals which fed on venomous snakes. According to Jean de Maleissye, Mithridates assumed that animals feeding on venomous snakes acquired some detoxifying property in their bodies, and their blood must contain attenuated or transformed components of the snake venom. The action of those components might be strengthening the body to resist against the venom instead of exerting toxic effect. Mithridates reasoned that, by drinking the blood of these animals, he could acquire the similar resistance to the snake venom as the animals feeding on the snakes. Similarly, he sought to harden himself against poison, and took daily sub-lethal doses to build tolerance. Mithridates is also said to have fashioned a 'universal antidote' to protect him from all earthly poisons. For nearly 2000 years, poisons were thought to be the proximate cause

of disease, and a complicated mixture of ingredients, called Mithridate

, was used to cure poisoning during the Renaissance

. An updated version of this cure, Theriacum Andromachi, was used well into the 19th century.

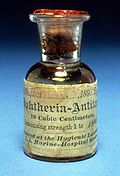

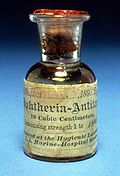

In 1888 Emile Roux and Alexandre Yersin

isolated diphtheria toxin

, and following the 1890 discovery by Behring

and Kitasato of antitoxin based immunity to diphtheria

and tetanus

, the antitoxin

became the first major success of modern therapeutic Immunology.

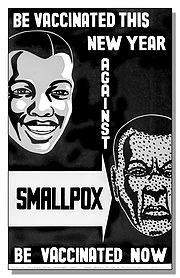

In Europe

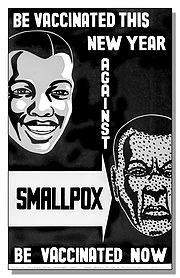

, the induction of active immunity emerged in an attempt to contain smallpox

. Immunization, however, had existed in various forms for at least a thousand years. The earliest use of immunization is unknown, however, around 1000 A.D. the Chinese

began practicing a form of immunization by drying and inhaling powders derived from the crusts of smallpox lesions. Around the fifteenth century in India

, the Ottoman Empire

, and east Africa

, the practice of variolation (poking the skin with powdered material derived from smallpox crusts) became quite common. Variolation was introduced to the west in the early 18th century by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

. In 1796, Edward Jenner

introduced the far safer method of inoculation

with the cowpox

virus, a non-fatal virus that also induced immunity to smallpox. The success and general acceptance of Jenner's procedure would later drive the general nature of vaccination

developed by Pasteur and others towards the end of the 19th century.

(or horse

) antibodies specific for a pathogen

or toxin

are transferred to non-immune

individuals. Passive immunization is used when there is a high risk of infection and insufficient time for the body to develop its own immune response, or to reduce the symptoms of ongoing or immunosuppressive

diseases. Passive immunity provides immediate protection, but the body does not develop memory, therefore the patient is at risk of being infected by the same pathogen later.

-mediated immunity conveyed to a fetus

by its mother during pregnancy. Maternal antibodies (MatAb) are passed through the placenta

to the fetus by an FcRn receptor on placental cells. This occurs around the third month of gestation

. IgG is the only antibody isotype

that can pass through the placenta. Passive immunity is also provided through the transfer of IgA

antibodies found in breast milk

that are transferred to the gut of the infant, protecting against bacterial infections, until the newborn can synthesize its own antibodies.

Artificially acquired passive immunity is a short-term immunization induced by the transfer of antibodies, which can be administered in several forms; as human or animal blood plasma, as pooled human immunoglobulin for intravenous (IVIG) or intramuscular (IG) use, and in the form of monoclonal antibodies

(MAb). Passive transfer is used prophylactically in the case of immunodeficiency

diseases, such as hypogammaglobulinemia

. It is also used in the treatment of several types of acute infection, and to treat poison

ing. Immunity derived from passive immunization lasts for only a short period of time, and there is also a potential risk for hypersensitivity

reactions, and serum sickness

, especially from gamma globulin

of non-human origin.

The artificial induction of passive immunity has been used for over a century to treat infectious disease, and prior to the advent of antibiotics, was often the only specific treatment for certain infections. Immunoglobulin therapy continued to be a first line therapy in the treatment of severe respiratory disease

s until the 1930’s, even after sulfonamide

lot antibiotics were introduced.

" of cell-mediated immunity, is conferred by the transfer of "sensitized" or activated T-cells from one individual into another. It is rarely used in humans because it requires histocompatible

(matched) donors, which are often difficult to find. In unmatched donors this type of transfer carries severe risks of graft versus host disease. It has, however, been used to treat certain diseases including some types of cancer

and immunodeficiency

. This type of transfer differs from a bone marrow transplant

, in which (undifferentiated) hematopoietic stem cells are transferred.

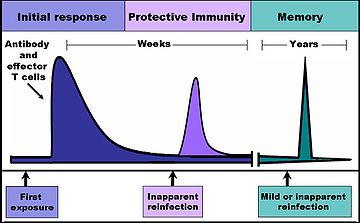

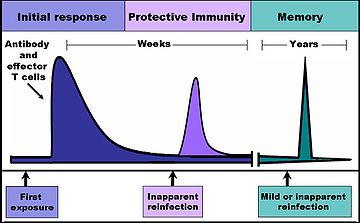

When B cells and T cells are activated by a pathogen, memory B-cells and T- cells develop. Throughout the lifetime of an animal these memory cells will “remember” each specific pathogen encountered, and are able to mount a strong response if the pathogen is detected again. This type of immunity is both active and adaptive because the body's immune system prepares itself for future challenges. Active immunity often involves both the cell-mediated and humoral aspects of immunity as well as input from the innate immune system

When B cells and T cells are activated by a pathogen, memory B-cells and T- cells develop. Throughout the lifetime of an animal these memory cells will “remember” each specific pathogen encountered, and are able to mount a strong response if the pathogen is detected again. This type of immunity is both active and adaptive because the body's immune system prepares itself for future challenges. Active immunity often involves both the cell-mediated and humoral aspects of immunity as well as input from the innate immune system

. The innate system is present from birth and protects an individual from pathogens regardless of experiences, whereas adaptive immunity arises only after an infection or immunization and hence is "acquired" during life.

(both acquired and congenital forms) and immunosuppression

.

, a substance that contains antigen. A vaccine stimulates a primary response against the antigen without causing symptoms of the disease. The term vaccination was coined by Edward Jenner

and adapted by Louis Pasteur

for his pioneering work in vaccination. The method Pasteur used entailed treating the infectious agents for those diseases so they lost the ability to cause serious disease. Pasteur adopted the name vaccine as a generic term in honor of Jenner's discovery, which Pasteur's work built upon. In 1807, the Bavarians became the first group to require that their military recruits be vaccinated against smallpox, as the spread of smallpox was linked to combat. Subsequently the practice of vaccination would increase with the spread of war.

In 1807, the Bavarians became the first group to require that their military recruits be vaccinated against smallpox, as the spread of smallpox was linked to combat. Subsequently the practice of vaccination would increase with the spread of war.

There are four types of traditional vaccine

s:

Most vaccines are given by hypodermic injection as they are not absorbed reliably through the gut. Live attenuated Polio and some Typhoid and Cholera

vaccines are given oral

ly in order to produce immunity based in the bowel.

Infection

An infection is the colonization of a host organism by parasite species. Infecting parasites seek to use the host's resources to reproduce, often resulting in disease...

, disease

Disease

A disease is an abnormal condition affecting the body of an organism. It is often construed to be a medical condition associated with specific symptoms and signs. It may be caused by external factors, such as infectious disease, or it may be caused by internal dysfunctions, such as autoimmune...

, or other unwanted biological invasion. Immunity involves both specific and non-specific components. The non-specific components act either as barriers or as eliminators of wide range of pathogens irrespective of antigenic specificity. Other components of the immune system

Immune system

An immune system is a system of biological structures and processes within an organism that protects against disease by identifying and killing pathogens and tumor cells. It detects a wide variety of agents, from viruses to parasitic worms, and needs to distinguish them from the organism's own...

adapt themselves to each new disease encountered and are able to generate pathogen-specific immunity.

Innate immunity, or nonspecific, immunity is the natural resistance with which a person is born. It provides resistance through several physical, chemical, and cellular approaches. Microbes first encounter the epithelial layers, physical barriers that line our skin and mucous membranes. Subsequent general defenses include secreted chemical signals (cytokines), antimicrobial substances, fever, and phagocytic activity associated with the inflammatory response. The phagocytes express cell surface receptors that can bind and respond to common molecular patterns expressed on the surface of invading microbes. Through these approaches, innate immunity can prevent the colonization, entry, and spread of microbes.

Adaptive immunity is often sub-divided into two major types depending on how the immunity was introduced. Naturally acquired immunity occurs through contact with a disease causing agent, when the contact was not deliberate, whereas artificially acquired immunity develops only through deliberate actions

Artificial induction of immunity

Artificial induction of immunity is the artificial induction of immunity to specific diseases - making people immune to disease by means other than waiting for them to catch the disease. The purpose is to reduce the risk of death and suffering....

such as vaccination. Both naturally and artificially acquired immunity can be further subdivided depending on whether immunity is induced in the host or passively transferred from a immune host. Passive immunity is acquired through transfer of antibodies or activated T-cells from an immune host, and is short lived -- usually lasting only a few months -- whereas active immunity is induced in the host itself by antigen, and lasts much longer, sometimes life-long. The diagram below summarizes these divisions of immunity.

Humoral immunity

The Humoral Immune Response is the aspect of immunity that is mediated by secreted antibodies produced in the cells of the B lymphocyte lineage . B Cells transform into plasma cells which secrete antibodies...

is the aspect of immunity that is mediated by secreted antibodies, whereas the protection provided by cell mediated immunity involves T-lymphocytes alone. Humoral immunity is active when the organism generates its own antibodies, and passive when antibodies are transferred between individuals. Similarly, cell mediated immunity is active when the organisms’ own T-cells are stimulated and passive when T cells come from another organism.

History of theories of immunity

Theurgy

Theurgy describes the practice of rituals, sometimes seen as magical in nature, performed with the intention of invoking the action or evoking the presence of one or more gods, especially with the goal of uniting with the divine, achieving henosis, and perfecting oneself.- Definitions :*Proclus...

punishment for “bad deeds” or “evil thoughts” visited upon the soul by the gods or by one’s enemies. Between the time of Hippocrates

Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Cos or Hippokrates of Kos was an ancient Greek physician of the Age of Pericles , and is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine...

and the 19th century, when the foundations of the scientific method were laid, diseases were attributed to an alteration or imbalance in one of the four humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile or black bile). Also popular during this time was the miasma theory

Miasma theory of disease

The miasma theory held that diseases such as cholera, chlamydia or the Black Death were caused by a miasma , a noxious form of "bad air"....

, which held that diseases such as cholera

Cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine that is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The main symptoms are profuse watery diarrhea and vomiting. Transmission occurs primarily by drinking or eating water or food that has been contaminated by the diarrhea of an infected person or the feces...

or the Black Plague were caused by a miasma, a noxious form of "bad air". If someone were exposed to the miasma, they could get the disease.

The modern word “immunity” derives from the Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

immunis, meaning exemption from military service, tax payments or other public services. The first written descriptions of the concept of immunity may have been made by the Athenian Thucydides

Thucydides

Thucydides was a Greek historian and author from Alimos. His History of the Peloponnesian War recounts the 5th century BC war between Sparta and Athens to the year 411 BC...

who, in 430 BC, described that when the plague hit Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

“the sick and the dying were tended by the pitying care of those who had recovered, because they knew the course of the disease and were themselves free from apprehensions. For no one was ever attacked a second time, or not with a fatal result”. The term “immunes”, is also found in the epic poem “Pharsalia

Pharsalia

The Pharsalia is a Roman epic poem by the poet Lucan, telling of the civil war between Julius Caesar and the forces of the Roman Senate led by Pompey the Great...

” written around 60 B.C. by the poet Marcus Annaeus Lucanus

Marcus Annaeus Lucanus

Marcus Annaeus Lucanus , better known in English as Lucan, was a Roman poet, born in Corduba , in the Hispania Baetica. Despite his short life, he is regarded as one of the outstanding figures of the Imperial Latin period...

to describe a North African tribe’s resistance to snake venom

Snake venom

Snake venom is highly modified saliva that is produced by special glands of certain species of snakes. The glands which secrete the zootoxin are a modification of the parotid salivary gland of other vertebrates, and are usually situated on each side of the head below and behind the eye,...

.

The first clinical description of immunity which arose from a specific disease causing organism is probably Kitab fi al-jadari wa-al-hasbah (A Treatise on Smallpox and Measles, translated 1848) written by the Islamic physician Al-Razi

Al-Razi

Muhammad ibn Zakariyā Rāzī , known as Rhazes or Rasis after medieval Latinists, was a Persian polymath,a prominent figure in Islamic Golden Age, physician, alchemist and chemist, philosopher, and scholar....

in the 9th century. In the treatise, Al Razi describes the clinical presentation of smallpox and measles and goes on to indicate that that exposure to these specific agents confers lasting immunity (although he does not use this term). However, it was with Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur was a French chemist and microbiologist born in Dole. He is remembered for his remarkable breakthroughs in the causes and preventions of diseases. His discoveries reduced mortality from puerperal fever, and he created the first vaccine for rabies and anthrax. His experiments...

’s Germ theory of disease

Germ theory of disease

The germ theory of disease, also called the pathogenic theory of medicine, is a theory that proposes that microorganisms are the cause of many diseases...

that the fledgling science of immunology

Immunology

Immunology is a broad branch of biomedical science that covers the study of all aspects of the immune system in all organisms. It deals with the physiological functioning of the immune system in states of both health and diseases; malfunctions of the immune system in immunological disorders ; the...

began to explain how bacteria caused disease, and how, following infection, the human body gained the ability to resist further infections.

Mithridates VI of Pontus

Mithridates VI or Mithradates VI Mithradates , from Old Persian Mithradatha, "gift of Mithra"; 134 BC – 63 BC, also known as Mithradates the Great and Eupator Dionysius, was king of Pontus and Armenia Minor in northern Anatolia from about 120 BC to 63 BC...

. To induce active immunity for snake venom, he recommended using a method similar to modern toxoid

Toxoid

A toxoid is a bacterial toxin whose toxicity has been weakened or suppressed either by chemical or heat treatment, while other properties, typically immunogenicity, are maintained. In international medical literature the preparation also is known as Anatoxin or Anatoxine...

serum therapy, by drinking the blood of animals which fed on venomous snakes. According to Jean de Maleissye, Mithridates assumed that animals feeding on venomous snakes acquired some detoxifying property in their bodies, and their blood must contain attenuated or transformed components of the snake venom. The action of those components might be strengthening the body to resist against the venom instead of exerting toxic effect. Mithridates reasoned that, by drinking the blood of these animals, he could acquire the similar resistance to the snake venom as the animals feeding on the snakes. Similarly, he sought to harden himself against poison, and took daily sub-lethal doses to build tolerance. Mithridates is also said to have fashioned a 'universal antidote' to protect him from all earthly poisons. For nearly 2000 years, poisons were thought to be the proximate cause

Proximate causation

In philosophy a proximate cause is an event which is closest to, or immediately responsible for causing, some observed result. This exists in contrast to a higher-level ultimate cause which is usually thought of as the "real" reason something occurred.* Example: Why did the ship sink?** Proximate...

of disease, and a complicated mixture of ingredients, called Mithridate

Mithridate

Mithridate, also known as mithridatium, mithridatum, or mithridaticum, is a semi-mythical remedy with as many as 65 ingredients, used as an antidote for poisoning, and said to be created by Mithradates VI Eupator of Pontus in the 1st century BC...

, was used to cure poisoning during the Renaissance

Renaissance

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that spanned roughly the 14th to the 17th century, beginning in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe. The term is also used more loosely to refer to the historical era, but since the changes of the Renaissance were not...

. An updated version of this cure, Theriacum Andromachi, was used well into the 19th century.

In 1888 Emile Roux and Alexandre Yersin

Alexandre Yersin

Alexandre Emile Jean Yersin was a Swiss and French physician and bacteriologist. He is remembered as the co-discoverer of the bacillus responsible for the bubonic plague or pest, which was later re-named in his honour .Yersin was born in 1863 in Aubonne, Canton of Vaud, Switzerland, to a family...

isolated diphtheria toxin

Diphtheria toxin

Diphtheria toxin is an exotoxin secreted by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, the pathogen bacterium that causes diphtheria. Unusually, the toxin gene is encoded by a bacteriophage...

, and following the 1890 discovery by Behring

Emil Adolf von Behring

Emil Adolf von Behring was a German physiologist who received the 1901 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, the first one so awarded.-Biography:...

and Kitasato of antitoxin based immunity to diphtheria

Diphtheria

Diphtheria is an upper respiratory tract illness caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, a facultative anaerobic, Gram-positive bacterium. It is characterized by sore throat, low fever, and an adherent membrane on the tonsils, pharynx, and/or nasal cavity...

and tetanus

Tetanus

Tetanus is a medical condition characterized by a prolonged contraction of skeletal muscle fibers. The primary symptoms are caused by tetanospasmin, a neurotoxin produced by the Gram-positive, rod-shaped, obligate anaerobic bacterium Clostridium tetani...

, the antitoxin

Antitoxin

An antitoxin is an antibody with the ability to neutralize a specific toxin. Antitoxins are produced by certain animals, plants, and bacteria. Although they are most effective in neutralizing toxins, they can kill bacteria and other microorganisms. Antitoxins are made within organisms, but can be...

became the first major success of modern therapeutic Immunology.

In Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

, the induction of active immunity emerged in an attempt to contain smallpox

Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease unique to humans, caused by either of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor. The disease is also known by the Latin names Variola or Variola vera, which is a derivative of the Latin varius, meaning "spotted", or varus, meaning "pimple"...

. Immunization, however, had existed in various forms for at least a thousand years. The earliest use of immunization is unknown, however, around 1000 A.D. the Chinese

Chinese people

The term Chinese people may refer to any of the following:*People with Han Chinese ethnicity ....

began practicing a form of immunization by drying and inhaling powders derived from the crusts of smallpox lesions. Around the fifteenth century in India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

, the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

, and east Africa

East Africa

East Africa or Eastern Africa is the easterly region of the African continent, variably defined by geography or geopolitics. In the UN scheme of geographic regions, 19 territories constitute Eastern Africa:...

, the practice of variolation (poking the skin with powdered material derived from smallpox crusts) became quite common. Variolation was introduced to the west in the early 18th century by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

The Lady Mary Wortley Montagu was an English aristocrat and writer. Montagu is today chiefly remembered for her letters, particularly her letters from Turkey, as wife to the British ambassador, which have been described by Billie Melman as “the very first example of a secular work by a woman about...

. In 1796, Edward Jenner

Edward Jenner

Edward Anthony Jenner was an English scientist who studied his natural surroundings in Berkeley, Gloucestershire...

introduced the far safer method of inoculation

Inoculation

Inoculation is the placement of something that will grow or reproduce, and is most commonly used in respect of the introduction of a serum, vaccine, or antigenic substance into the body of a human or animal, especially to produce or boost immunity to a specific disease...

with the cowpox

Cowpox

Cowpox is a skin disease caused by a virus known as the Cowpox virus. The pox is related to the vaccinia virus and got its name from the distribution of the disease when dairymaids touched the udders of infected cows. The ailment manifests itself in the form of red blisters and is transmitted by...

virus, a non-fatal virus that also induced immunity to smallpox. The success and general acceptance of Jenner's procedure would later drive the general nature of vaccination

Vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of antigenic material to stimulate the immune system of an individual to develop adaptive immunity to a disease. Vaccines can prevent or ameliorate the effects of infection by many pathogens...

developed by Pasteur and others towards the end of the 19th century.

Passive immunity

Passive immunity is the transfer of active immunity, in the form of readymade antibodies, from one individual to another. Passive immunity can occur naturally, when maternal antibodies are transferred to the fetus through the placenta, and can also be induced artificially, when high levels of humanHuman

Humans are the only living species in the Homo genus...

(or horse

Horse

The horse is one of two extant subspecies of Equus ferus, or the wild horse. It is a single-hooved mammal belonging to the taxonomic family Equidae. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million years from a small multi-toed creature into the large, single-toed animal of today...

) antibodies specific for a pathogen

Pathogen

A pathogen gignomai "I give birth to") or infectious agent — colloquially, a germ — is a microbe or microorganism such as a virus, bacterium, prion, or fungus that causes disease in its animal or plant host...

or toxin

Toxin

A toxin is a poisonous substance produced within living cells or organisms; man-made substances created by artificial processes are thus excluded...

are transferred to non-immune

Immune system

An immune system is a system of biological structures and processes within an organism that protects against disease by identifying and killing pathogens and tumor cells. It detects a wide variety of agents, from viruses to parasitic worms, and needs to distinguish them from the organism's own...

individuals. Passive immunization is used when there is a high risk of infection and insufficient time for the body to develop its own immune response, or to reduce the symptoms of ongoing or immunosuppressive

Immunosuppression

Immunosuppression involves an act that reduces the activation or efficacy of the immune system. Some portions of the immune system itself have immuno-suppressive effects on other parts of the immune system, and immunosuppression may occur as an adverse reaction to treatment of other...

diseases. Passive immunity provides immediate protection, but the body does not develop memory, therefore the patient is at risk of being infected by the same pathogen later.

Naturally acquired passive immunity

Maternal passive immunity is a type of naturally acquired passive immunity, and refers to antibodyAntibody

An antibody, also known as an immunoglobulin, is a large Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique part of the foreign target, termed an antigen...

-mediated immunity conveyed to a fetus

Fetus

A fetus is a developing mammal or other viviparous vertebrate after the embryonic stage and before birth.In humans, the fetal stage of prenatal development starts at the beginning of the 11th week in gestational age, which is the 9th week after fertilization.-Etymology and spelling variations:The...

by its mother during pregnancy. Maternal antibodies (MatAb) are passed through the placenta

Placenta

The placenta is an organ that connects the developing fetus to the uterine wall to allow nutrient uptake, waste elimination, and gas exchange via the mother's blood supply. "True" placentas are a defining characteristic of eutherian or "placental" mammals, but are also found in some snakes and...

to the fetus by an FcRn receptor on placental cells. This occurs around the third month of gestation

Gestation

Gestation is the carrying of an embryo or fetus inside a female viviparous animal. Mammals during pregnancy can have one or more gestations at the same time ....

. IgG is the only antibody isotype

Isotype (immunology)

An isotype usually refers to any related proteins/genes from a particular gene family. In immunology, the "immunoglobulin isotype" refers to the genetic variations or differences in the constant regions of the heavy and light chains...

that can pass through the placenta. Passive immunity is also provided through the transfer of IgA

IGA

Iga or IGA may stand for:-Given name:* a female given name of Polish origin. The name originates from the female given name Jadwiga and stands for gia,or gina in the USA....

antibodies found in breast milk

Breast milk

Breast milk, more specifically human milk, is the milk produced by the breasts of a human female for her infant offspring...

that are transferred to the gut of the infant, protecting against bacterial infections, until the newborn can synthesize its own antibodies.

Artificially acquired passive immunity

see also: Temporarily-induced immunityArtificially acquired passive immunity is a short-term immunization induced by the transfer of antibodies, which can be administered in several forms; as human or animal blood plasma, as pooled human immunoglobulin for intravenous (IVIG) or intramuscular (IG) use, and in the form of monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies are monospecific antibodies that are the same because they are made by identical immune cells that are all clones of a unique parent cell....

(MAb). Passive transfer is used prophylactically in the case of immunodeficiency

Immunodeficiency

Immunodeficiency is a state in which the immune system's ability to fight infectious disease is compromised or entirely absent. Immunodeficiency may also decrease cancer immunosurveillance. Most cases of immunodeficiency are acquired but some people are born with defects in their immune system,...

diseases, such as hypogammaglobulinemia

Hypogammaglobulinemia

Hypogammaglobulinemia is a type of immune disorder characterized by a reduction in all types of gamma globulins.Hypogammaglobulinemia is a characteristic of common variable immunodeficiency.-Terminology:...

. It is also used in the treatment of several types of acute infection, and to treat poison

Poison

In the context of biology, poisons are substances that can cause disturbances to organisms, usually by chemical reaction or other activity on the molecular scale, when a sufficient quantity is absorbed by an organism....

ing. Immunity derived from passive immunization lasts for only a short period of time, and there is also a potential risk for hypersensitivity

Hypersensitivity

Hypersensitivity refers to undesirable reactions produced by the normal immune system, including allergies and autoimmunity. These reactions may be damaging, uncomfortable, or occasionally fatal. Hypersensitivity reactions require a pre-sensitized state of the host. The four-group classification...

reactions, and serum sickness

Serum sickness

Serum sickness in humans is a reaction to proteins in antiserum derived from an non-human animal source. It is a type of hypersensitivity, specifically immune complex hypersensitivity . The term serum sickness–like reaction is occasionally used to refer to similar illnesses that arise from the...

, especially from gamma globulin

Gamma globulin

Gamma globulins are a class of globulins, identified by their position after serum protein electrophoresis. The most significant gamma globulins are immunoglobulins , more commonly known as antibodies, although some Igs are not gamma globulins, and some gamma globulins are not Igs.-Use as medical...

of non-human origin.

The artificial induction of passive immunity has been used for over a century to treat infectious disease, and prior to the advent of antibiotics, was often the only specific treatment for certain infections. Immunoglobulin therapy continued to be a first line therapy in the treatment of severe respiratory disease

Respiratory disease

Respiratory disease is a medical term that encompasses pathological conditions affecting the organs and tissues that make gas exchange possible in higher organisms, and includes conditions of the upper respiratory tract, trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, alveoli, pleura and pleural cavity, and the...

s until the 1930’s, even after sulfonamide

Sulfonamide (medicine)

Sulfonamide or sulphonamide is the basis of several groups of drugs. The original antibacterial sulfonamides are synthetic antimicrobial agents that contain the sulfonamide group. Some sulfonamides are also devoid of antibacterial activity, e.g., the anticonvulsant sultiame...

lot antibiotics were introduced.

Passive transfer of cell-mediated immunity

Passive or "adoptive transferAdoptive immunity

Adoptive immunity acts in a host after his immunological components are withdrawn, their immunological activity is modified extracorporeally, and then reinfused into the same host. This process in its former part is analogous to adoption: a child is once adopted out from his home, grown up, and...

" of cell-mediated immunity, is conferred by the transfer of "sensitized" or activated T-cells from one individual into another. It is rarely used in humans because it requires histocompatible

Histocompatibility

Histocompatibility is the property of having the same, or mostly the same, alleles of a set of genes called the major histocompatibility complex. These genes are expressed in most tissues as antigens, to which the immune system makes antibodies...

(matched) donors, which are often difficult to find. In unmatched donors this type of transfer carries severe risks of graft versus host disease. It has, however, been used to treat certain diseases including some types of cancer

Cancer

Cancer , known medically as a malignant neoplasm, is a large group of different diseases, all involving unregulated cell growth. In cancer, cells divide and grow uncontrollably, forming malignant tumors, and invade nearby parts of the body. The cancer may also spread to more distant parts of the...

and immunodeficiency

Immunodeficiency

Immunodeficiency is a state in which the immune system's ability to fight infectious disease is compromised or entirely absent. Immunodeficiency may also decrease cancer immunosurveillance. Most cases of immunodeficiency are acquired but some people are born with defects in their immune system,...

. This type of transfer differs from a bone marrow transplant

Bone marrow transplant

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is the transplantation of multipotent hematopoietic stem cell or blood, usually derived from bone marrow, peripheral blood stem cells, or umbilical cord blood...

, in which (undifferentiated) hematopoietic stem cells are transferred.

Active immunity

Innate immune system

The innate immune system, also known as non-specific immune system and secondary line of defence, comprises the cells and mechanisms that defend the host from infection by other organisms in a non-specific manner...

. The innate system is present from birth and protects an individual from pathogens regardless of experiences, whereas adaptive immunity arises only after an infection or immunization and hence is "acquired" during life.

Naturally acquired active immunity

Naturally acquired active immunity occurs when a person is exposed to a live pathogen, and develops a primary immune response, which leads to immunological memory. This type of immunity is “natural” because it is not induced by deliberate exposure. Many disorders of immune system function can affect the formation of active immunity such as immunodeficiencyImmunodeficiency

Immunodeficiency is a state in which the immune system's ability to fight infectious disease is compromised or entirely absent. Immunodeficiency may also decrease cancer immunosurveillance. Most cases of immunodeficiency are acquired but some people are born with defects in their immune system,...

(both acquired and congenital forms) and immunosuppression

Immunosuppression

Immunosuppression involves an act that reduces the activation or efficacy of the immune system. Some portions of the immune system itself have immuno-suppressive effects on other parts of the immune system, and immunosuppression may occur as an adverse reaction to treatment of other...

.

Artificially acquired active immunity

Artificially acquired active immunity can be induced by a vaccineVaccine

A vaccine is a biological preparation that improves immunity to a particular disease. A vaccine typically contains an agent that resembles a disease-causing microorganism, and is often made from weakened or killed forms of the microbe or its toxins...

, a substance that contains antigen. A vaccine stimulates a primary response against the antigen without causing symptoms of the disease. The term vaccination was coined by Edward Jenner

Edward Jenner

Edward Anthony Jenner was an English scientist who studied his natural surroundings in Berkeley, Gloucestershire...

and adapted by Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur was a French chemist and microbiologist born in Dole. He is remembered for his remarkable breakthroughs in the causes and preventions of diseases. His discoveries reduced mortality from puerperal fever, and he created the first vaccine for rabies and anthrax. His experiments...

for his pioneering work in vaccination. The method Pasteur used entailed treating the infectious agents for those diseases so they lost the ability to cause serious disease. Pasteur adopted the name vaccine as a generic term in honor of Jenner's discovery, which Pasteur's work built upon.

There are four types of traditional vaccine

Vaccine

A vaccine is a biological preparation that improves immunity to a particular disease. A vaccine typically contains an agent that resembles a disease-causing microorganism, and is often made from weakened or killed forms of the microbe or its toxins...

s:

- Inactivated vaccines are composed of micro-organisms that have been killed with chemicals and/or heat and are no longer infectious. Examples are vaccines against flu, choleraCholeraCholera is an infection of the small intestine that is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The main symptoms are profuse watery diarrhea and vomiting. Transmission occurs primarily by drinking or eating water or food that has been contaminated by the diarrhea of an infected person or the feces...

, plague, and hepatitis AHepatitis AHepatitis A is an acute infectious disease of the liver caused by the hepatitis A virus , an RNA virus, usually spread the fecal-oral route; transmitted person-to-person by ingestion of contaminated food or water or through direct contact with an infectious person...

. Most vaccines of this type are likely to require booster shots. - Live, attenuatedAttenuator (genetics)Attenuation is a regulatory feature found throughout Archaea and Bacteria causing premature termination of transcription. Attenuators are 5'-cis acting regulatory regions which fold into one of two alternative RNA structures which determine the success of transcription...

vaccines are composed of micro-organisms that have been cultivated under conditions which disable their ability to induce disease. These responses are more durable and do not generally require booster shots. Examples include yellow feverYellow feverYellow fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic disease. The virus is a 40 to 50 nm enveloped RNA virus with positive sense of the Flaviviridae family....

, measlesMeaslesMeasles, also known as rubeola or morbilli, is an infection of the respiratory system caused by a virus, specifically a paramyxovirus of the genus Morbillivirus. Morbilliviruses, like other paramyxoviruses, are enveloped, single-stranded, negative-sense RNA viruses...

, rubellaRubellaRubella, commonly known as German measles, is a disease caused by the rubella virus. The name "rubella" is derived from the Latin, meaning little red. Rubella is also known as German measles because the disease was first described by German physicians in the mid-eighteenth century. This disease is...

, and mumpsMumpsMumps is a viral disease of the human species, caused by the mumps virus. Before the development of vaccination and the introduction of a vaccine, it was a common childhood disease worldwide...

. - ToxoidToxoidA toxoid is a bacterial toxin whose toxicity has been weakened or suppressed either by chemical or heat treatment, while other properties, typically immunogenicity, are maintained. In international medical literature the preparation also is known as Anatoxin or Anatoxine...

s are inactivated toxic compounds from micro-organisms in cases where these (rather than the micro-organism itself) cause illness, used prior to an encounter with the toxin of the micro-organism. Examples of toxoid-based vaccines include tetanusTetanusTetanus is a medical condition characterized by a prolonged contraction of skeletal muscle fibers. The primary symptoms are caused by tetanospasmin, a neurotoxin produced by the Gram-positive, rod-shaped, obligate anaerobic bacterium Clostridium tetani...

and diphtheriaDiphtheriaDiphtheria is an upper respiratory tract illness caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, a facultative anaerobic, Gram-positive bacterium. It is characterized by sore throat, low fever, and an adherent membrane on the tonsils, pharynx, and/or nasal cavity...

. - SubunitSubunitA subunit is a subdivision of a larger unit.*In military organizations, a sub-unit is smaller in size than a battalion and is commanded by an Officer Commanding.*In chemistry, the term can refer to a monomer...

-vaccines are composed of small fragments of disease causing organisms. A characteristic example is the subunit vaccine against Hepatitis B virusHepatitis B virusHepatitis B is an infectious illness caused by hepatitis B virus which infects the liver of hominoidea, including humans, and causes an inflammation called hepatitis. Originally known as "serum hepatitis", the disease has caused epidemics in parts of Asia and Africa, and it is endemic in China...

.

Most vaccines are given by hypodermic injection as they are not absorbed reliably through the gut. Live attenuated Polio and some Typhoid and Cholera

Cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine that is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The main symptoms are profuse watery diarrhea and vomiting. Transmission occurs primarily by drinking or eating water or food that has been contaminated by the diarrhea of an infected person or the feces...

vaccines are given oral

Mouth

The mouth is the first portion of the alimentary canal that receives food andsaliva. The oral mucosa is the mucous membrane epithelium lining the inside of the mouth....

ly in order to produce immunity based in the bowel.

See also

- AntiserumAntiserumAntiserum is blood serum containing polyclonal antibodies. Antiserum is used to pass on passive immunity to many diseases. Passive antibody transfusion from a previous human survivor is the only known effective treatment for Ebola infection .The most common use of antiserum in humans is as...

- AntiveninAntiveninAntivenom is a biological product used in the treatment of venomous bites or stings. Antivenom is created by milking venom from the desired snake, spider or insect. The venom is then diluted and injected into a horse, sheep or goat...

- Hoskins effect

- ImmunologyImmunologyImmunology is a broad branch of biomedical science that covers the study of all aspects of the immune system in all organisms. It deals with the physiological functioning of the immune system in states of both health and diseases; malfunctions of the immune system in immunological disorders ; the...

- InoculationInoculationInoculation is the placement of something that will grow or reproduce, and is most commonly used in respect of the introduction of a serum, vaccine, or antigenic substance into the body of a human or animal, especially to produce or boost immunity to a specific disease...

- Plague immunization