Adlai E. Stevenson

Encyclopedia

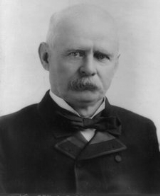

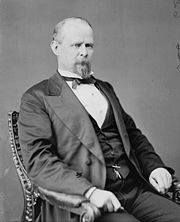

Adlai Ewing Stevenson I (October 23, 1835 – June 14, 1914) was a Congressman

from Illinois

. He was Assistant Postmaster General

of the United States during Grover Cleveland

's first administration (1885–1889) and 23rd Vice President of the United States

(1893–1897) during Cleveland's second administration. In 1900, he was the unsuccessful Democratic

candidate for Vice President on a ticket with William Jennings Bryan

.

s of Scots-Irish descent. John Turner Stevenson's grandfather, William was born in Roxburgh

, Scotland

then migrated to and from Ulster

around 1748, settling first in Pennsylvania and then in North Carolina in the County of Iredell

. The family moved to Kentucky in 1813. Stevenson was born on the family farm in Christian County, Kentucky

. He attended the common school in Blue Water, Kentucky. In 1852, when he was 16, frost killed the family's tobacco crop. His father set free their few slaves and the family moved to Bloomington, Illinois

, where his father then operated a sawmill. Stevenson attended Illinois Wesleyan University

at Bloomington and ultimately graduated from Centre College

, in Danville, Kentucky

; at the latter he was a part of Phi Delta Theta

. His father's death prompted Adlai to return from Kentucky to Illinois to run the sawmill.

Stevenson was admitted to the bar in 1858, at age 23, and commenced practice in Metamora

, in Woodford County, Illinois. As a young lawyer, Stevenson encountered such celebrated Illinois attorneys as Stephen A. Douglas

and Abraham Lincoln

, campaigning for Douglas in his 1858 Senate race against Lincoln. Stevenson's dislike of Lincoln might have been prompted by a contentious meeting between the two, where Lincoln made several witty quips disparaging Stevenson. Stevenson also made speeches against the "Know-Nothing" movement, a nativist group opposed to immigrants and Catholics. That stand helped cement his support in Illinois' large German and Irish communities. In a predominantly Republican area, the Democratic Stevenson won friends through his storytelling and his warm and engaging personality.

Stevenson was appointed master in chancery (an aide in a court of equity), his first public office, which he held during the Civil War. In 1864 Stevenson was a presidential elector for the Democratic ticket; he was also elected district attorney.

Stevenson was appointed master in chancery (an aide in a court of equity), his first public office, which he held during the Civil War. In 1864 Stevenson was a presidential elector for the Democratic ticket; he was also elected district attorney.

In 1866 he married Letitia Green, with whom he had fallen in love nine years earlier, at Centre College (her father, the Reverend Lewis Warner Green, the head of the college, had not agreed to the marriage, but he had died, and Letitia and her mother - who also opposed the marriage - had subsequently moved to Bloomington). They had three daughters and a son, Lewis G. Stevenson. Letitia helped establish the Daughters of the American Revolution

as a way of healing the divisions between the North and South after the Civil War, and succeeded the wife of Benjamin Harrison

as the DAR's second president-general.

In 1868, at the end of his term as district attorney, he entered law practice with his cousin, James S. Ewing, moving with his wife back to Bloomington, settling in a large house on Franklin Square. Stevenson & Ewing would become one of the state's most prominent law firms. Ewing would later became the U.S. ambassador to Belgium.

In 1874, Stevenson was elected as a Democrat to the Forty-fourth Congress

, serving from March 4, 1875 to March 4, 1877. Local Republican newspapers painted him as a "vile secessionist," but the continuing hardships from the Panic of 1873

caused voters to sweep him into office with the first Democratic congressional majority since the Civil War.

In 1876, Stevenson was an unsuccessful candidate for reelection. The Republican presidential ticket, headed by Rutherford B. Hayes

carried his district, and Stevenson was narrowly defeated, getting 49.6 percent of the vote. In 1878, he ran on both the Democratic and Greenback tickets and won, returning to a House from which one-third of his earlier colleagues had either voluntarily retired or been removed by the voters. In 1880, again a presidential election year, he once more lost narrowly, and he lost again in 1882 in his final race for Congress.

in 1885. During that time he fired over 40,000 Republican

workers and replaced them with Democrats

from the South. The Republican-controlled U.S. Congress did not forget this: when Stevenson was nominated for a federal judgeship, he was defeated for confirmation by the same people who never forgot his 1885 purge.

supporter. The winning Cleveland-Stevenson ticket carried Illinois, although not Stevenson's home district.

Civil service reformers held out hope for the second Cleveland administration but saw Vice President Stevenson as a symbol of the spoils system

. He never hesitated to feed names of Democrats to the Post Office Department. Once he called at the US Treasury Department to protest against an appointment and was shown a letter he had written endorsing the candidate. Stevenson told the treasury officials not to pay attention to any of his written endorsements; if he really favored someone he would tell them personally.

A habitual cigar

-smoker, Cleveland developed cancer of the mouth

that required immediate surgery in the summer of 1893. The president insisted that the surgery be kept secret to avoid another panic on Wall Street

. While on a yacht

in New York harbor

that summer, Cleveland had his entire upper jaw removed and replaced with an artificial device, an operation that left no outward scar. The cancer surgery remained secret for another quarter century. Cleveland's aides explained that he had merely had dental work. His vice president little realized how close he came to the presidency that summer.

Adlai Stevenson enjoyed his role as vice president, presiding over the U.S. Senate, "the most august legislative assembly known to men." He won praise for ruling in a dignified, nonpartisan manner. In personal appearance he stood six feet tall and was "of fine personal bearing and uniformly courteous to all." Although he was often a guest at the White House, Stevenson admitted that he was less an adviser to the president than "the neighbor to his counsels." He credited the President with being "courteous at all times" but noted that "no guards were necessary to the preservation of his dignity. No one would have thought of undue familiarity." For his part, President Cleveland snorted that the Vice President had surrounded himself with a coterie of free-silver men dubbed the "Stevenson cabinet." The president even mused that the economy had gotten so bad and the Democratic party so divided that "the logical thing for me to do ... was to resign and hand the Executive branch to Mr. Stevenson," joking that he would try to get his friends jobs in Stevenson's new cabinet.

, who delivered his fiery "Cross of Gold" speech in favor of a free-silver plank in the platform. Not only did the Democrats repudiate Cleveland by embracing free silver, but they also nominated Bryan for president. Many Cleveland Democrats, including most Democratic newspapers, refused to support Bryan, but Vice President Stevenson loyally endorsed the ticket.

After the 1896 election, Bryan became the titular leader of the Democrats and frontrunner for the nomination in 1900. Much of the newspaper speculation about who would run as the party's vice-presidential candidate centered on Indiana Senator Benjamin Shively. When reporter Arthur Wallace Dunn interviewed Shively at the convention, the senator said he "did not want the glory of a defeat as a vice presidential candidate." Disappointed, Dunn said that he still had to file a story on the vice-presidential nomination, and then added: "I believe I'll write a piece about old Uncle Adlai." Shively responded

For the rest of the day, Dunn heard other favorable remarks about Stevenson, and by that night the former vice president was the leading contender, since no one else was "very anxious to be the tail of what they considered was a forlorn hope

ticket."

The Populists had already nominated the ticket of Bryan and Charles A. Towne

, a pro-silver Republican from Minnesota

, with the tacit understanding that Towne would step aside if the Democrats nominated someone else. Bryan preferred his good friend Towne, but Democrats wanted one of their own, and the regular element of the party felt comfortable with Stevenson. Towne withdrew and campaigned for Bryan and Stevenson. As a result, Stevenson, who had run with Cleveland in 1892, now ran in 1900 with Cleveland's opponent Bryan. Twenty-five years senior to Bryan, Stevenson added age and experience to the ticket. Nevertheless, their effort failed badly against the Republican ticket of McKinley

and Roosevelt

. (Stevenson's role in the race is perhaps more distinguished by his being the first Vice President to win nomination for that office with a different running mate, after having completed his first term. As of 2008, Republican Charles W. Fairbanks

's failure to win a second VP term in 1916 is the only example since.)

in 1908, at age 72, narrowly losing. In 1909 he was brought in by founder Jesse Grant Chapline

to aid distance learning school La Salle Extension University

. After that, he retired to Bloomington, where his Republican neighbors described him as "windy but amusing." He died in Chicago on June 14, 1914. His body is interred in a family plot in Evergreen Cemetery, Bloomington, Illinois

.

Stevenson's son, Lewis G. Stevenson, was Illinois secretary of state (1914–1917). Stevenson's grandson Adlai Ewing Stevenson II was Democratic candidate for President of the United States in 1952 and 1956 and Governor of Illinois

. His great-grandson, Adlai Ewing Stevenson III

, was a U.S. senator

from Illinois

from 1970 to 1981 and an unsuccessful candidate for Governor of Illinois

in 1982 and 1986.

(who also gave Stevenson an honorary degree in 1893), built and named a residence hall after Stevenson - Stevenson House - as part of a new campus quadrangle. Stevenson House was renovated in 1995. http://www.centre.edu/campusbuildings/slideshow_quad/index.html

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

from Illinois

Illinois

Illinois is the fifth-most populous state of the United States of America, and is often noted for being a microcosm of the entire country. With Chicago in the northeast, small industrial cities and great agricultural productivity in central and northern Illinois, and natural resources like coal,...

. He was Assistant Postmaster General

United States Postmaster General

The United States Postmaster General is the Chief Executive Officer of the United States Postal Service. The office, in one form or another, is older than both the United States Constitution and the United States Declaration of Independence...

of the United States during Grover Cleveland

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States. Cleveland is the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms and therefore is the only individual to be counted twice in the numbering of the presidents...

's first administration (1885–1889) and 23rd Vice President of the United States

Vice President of the United States

The Vice President of the United States is the holder of a public office created by the United States Constitution. The Vice President, together with the President of the United States, is indirectly elected by the people, through the Electoral College, to a four-year term...

(1893–1897) during Cleveland's second administration. In 1900, he was the unsuccessful Democratic

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

candidate for Vice President on a ticket with William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan was an American politician in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. He was a dominant force in the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, standing three times as its candidate for President of the United States...

.

Early life

Stevenson's parents, John Turner Stevenson and Eliza Ewing Stevenson, were WesleyanWesleyan Church

"Wesleyan" has been used in the title of a number of historic and current denominations, although the subject of this article is the only denomination to use that specific title...

s of Scots-Irish descent. John Turner Stevenson's grandfather, William was born in Roxburgh

Roxburghshire

Roxburghshire or the County of Roxburgh is a registration county of Scotland. It borders Dumfries to the west, Selkirk to the north-west, and Berwick to the north. To the south-east it borders Cumbria and Northumberland in England.It was named after the Royal Burgh of Roxburgh...

, Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

then migrated to and from Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

around 1748, settling first in Pennsylvania and then in North Carolina in the County of Iredell

Iredell County, North Carolina

Iredell County, along with Moore County in the eastern Piedmont, are among a very few counties in the United States sharing borders with nine adjacent counties.-Demographics:...

. The family moved to Kentucky in 1813. Stevenson was born on the family farm in Christian County, Kentucky

Christian County, Kentucky

Christian County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. It was formed in 1797. As of 2000, its population was 72,265. Its county seat is Hopkinsville, Kentucky...

. He attended the common school in Blue Water, Kentucky. In 1852, when he was 16, frost killed the family's tobacco crop. His father set free their few slaves and the family moved to Bloomington, Illinois

Bloomington, Illinois

Bloomington is a city in McLean County, Illinois, United States and the county seat. It is adjacent to Normal, Illinois, and is the more populous of the two principal municipalities of the Bloomington-Normal metropolitan area...

, where his father then operated a sawmill. Stevenson attended Illinois Wesleyan University

Illinois Wesleyan University

Illinois Wesleyan University is an independent undergraduate university located in Bloomington, Illinois. Founded in 1850, the central portion of the present campus was acquired in 1854 with the first building erected in 1856...

at Bloomington and ultimately graduated from Centre College

Centre College

Centre College is a private liberal arts college in Danville, Kentucky, USA, a community of approximately 16,000 in Boyle County south of Lexington, KY. Centre is an exclusively undergraduate four-year institution. Centre was founded by Presbyterian leaders, with whom it maintains a loose...

, in Danville, Kentucky

Danville, Kentucky

Danville is a city in and the county seat of Boyle County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 16,218 at the 2010 census.Danville is the principal city of the Danville Micropolitan Statistical Area, which includes all of Boyle and Lincoln counties....

; at the latter he was a part of Phi Delta Theta

Phi Delta Theta

Phi Delta Theta , also known as Phi Delt, is an international fraternity founded at Miami University in 1848 and headquartered in Oxford, Ohio. Phi Delta Theta, Beta Theta Pi, and Sigma Chi form the Miami Triad. The fraternity has about 169 active chapters and colonies in over 43 U.S...

. His father's death prompted Adlai to return from Kentucky to Illinois to run the sawmill.

Stevenson was admitted to the bar in 1858, at age 23, and commenced practice in Metamora

Metamora, Illinois

Metamora is a village in Woodford County, Illinois, United States. The population was 2,700 at the 2000 census. Metamora is a growing suburb of Peoria and is part of the Peoria, Illinois Metropolitan Statistical Area.-Geography:...

, in Woodford County, Illinois. As a young lawyer, Stevenson encountered such celebrated Illinois attorneys as Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas was an American politician from the western state of Illinois, and was the Northern Democratic Party nominee for President in 1860. He lost to the Republican Party's candidate, Abraham Lincoln, whom he had defeated two years earlier in a Senate contest following a famed...

and Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

, campaigning for Douglas in his 1858 Senate race against Lincoln. Stevenson's dislike of Lincoln might have been prompted by a contentious meeting between the two, where Lincoln made several witty quips disparaging Stevenson. Stevenson also made speeches against the "Know-Nothing" movement, a nativist group opposed to immigrants and Catholics. That stand helped cement his support in Illinois' large German and Irish communities. In a predominantly Republican area, the Democratic Stevenson won friends through his storytelling and his warm and engaging personality.

Marriage and political life, 1860-1884

In 1866 he married Letitia Green, with whom he had fallen in love nine years earlier, at Centre College (her father, the Reverend Lewis Warner Green, the head of the college, had not agreed to the marriage, but he had died, and Letitia and her mother - who also opposed the marriage - had subsequently moved to Bloomington). They had three daughters and a son, Lewis G. Stevenson. Letitia helped establish the Daughters of the American Revolution

Daughters of the American Revolution

The Daughters of the American Revolution is a lineage-based membership organization for women who are descended from a person involved in United States' independence....

as a way of healing the divisions between the North and South after the Civil War, and succeeded the wife of Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison was the 23rd President of the United States . Harrison, a grandson of President William Henry Harrison, was born in North Bend, Ohio, and moved to Indianapolis, Indiana at age 21, eventually becoming a prominent politician there...

as the DAR's second president-general.

In 1868, at the end of his term as district attorney, he entered law practice with his cousin, James S. Ewing, moving with his wife back to Bloomington, settling in a large house on Franklin Square. Stevenson & Ewing would become one of the state's most prominent law firms. Ewing would later became the U.S. ambassador to Belgium.

In 1874, Stevenson was elected as a Democrat to the Forty-fourth Congress

44th United States Congress

The Forty-fourth United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1875 to March 4, 1877, during the seventh and...

, serving from March 4, 1875 to March 4, 1877. Local Republican newspapers painted him as a "vile secessionist," but the continuing hardships from the Panic of 1873

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 triggered a severe international economic depression in both Europe and the United States that lasted until 1879, and even longer in some countries. The depression was known as the Great Depression until the 1930s, but is now known as the Long Depression...

caused voters to sweep him into office with the first Democratic congressional majority since the Civil War.

In 1876, Stevenson was an unsuccessful candidate for reelection. The Republican presidential ticket, headed by Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes was the 19th President of the United States . As president, he oversaw the end of Reconstruction and the United States' entry into the Second Industrial Revolution...

carried his district, and Stevenson was narrowly defeated, getting 49.6 percent of the vote. In 1878, he ran on both the Democratic and Greenback tickets and won, returning to a House from which one-third of his earlier colleagues had either voluntarily retired or been removed by the voters. In 1880, again a presidential election year, he once more lost narrowly, and he lost again in 1882 in his final race for Congress.

Election of Grover Cleveland in 1884 and the U.S. Post Office

Stevenson served as first assistant postmaster general under Grover ClevelandGrover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States. Cleveland is the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms and therefore is the only individual to be counted twice in the numbering of the presidents...

in 1885. During that time he fired over 40,000 Republican

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

workers and replaced them with Democrats

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

from the South. The Republican-controlled U.S. Congress did not forget this: when Stevenson was nominated for a federal judgeship, he was defeated for confirmation by the same people who never forgot his 1885 purge.

Vice President, 1893-1897

In 1892, when the Democrats chose Cleveland once again as their standard bearer, they appeased party regulars by the nomination of Stevenson, "headsman of the post-office," for vice president. As a supporter of using greenbacks and free silver to inflate the currency and alleviate economic distress in the rural districts, Stevenson balanced the ticket headed by Cleveland, the hard-money, gold-standardGold standard

The gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is a fixed mass of gold. There are distinct kinds of gold standard...

supporter. The winning Cleveland-Stevenson ticket carried Illinois, although not Stevenson's home district.

Civil service reformers held out hope for the second Cleveland administration but saw Vice President Stevenson as a symbol of the spoils system

Spoils system

In the politics of the United States, a spoil system is a practice where a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its voters as a reward for working toward victory, and as an incentive to keep working for the party—as opposed to a system of awarding offices on the...

. He never hesitated to feed names of Democrats to the Post Office Department. Once he called at the US Treasury Department to protest against an appointment and was shown a letter he had written endorsing the candidate. Stevenson told the treasury officials not to pay attention to any of his written endorsements; if he really favored someone he would tell them personally.

A habitual cigar

Cigar

A cigar is a tightly-rolled bundle of dried and fermented tobacco that is ignited so that its smoke may be drawn into the mouth. Cigar tobacco is grown in significant quantities in Brazil, Cameroon, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Indonesia, Mexico, Nicaragua, Philippines, and the Eastern...

-smoker, Cleveland developed cancer of the mouth

Oral cancer

Oral cancer is a subtype of head and neck cancer, is any cancerous tissue growth located in the oral cavity. It may arise as a primary lesion originating in any of the oral tissues, by metastasis from a distant site of origin, or by extension from a neighboring anatomic structure, such as the...

that required immediate surgery in the summer of 1893. The president insisted that the surgery be kept secret to avoid another panic on Wall Street

Wall Street

Wall Street refers to the financial district of New York City, named after and centered on the eight-block-long street running from Broadway to South Street on the East River in Lower Manhattan. Over time, the term has become a metonym for the financial markets of the United States as a whole, or...

. While on a yacht

Yacht

A yacht is a recreational boat or ship. The term originated from the Dutch Jacht meaning "hunt". It was originally defined as a light fast sailing vessel used by the Dutch navy to pursue pirates and other transgressors around and into the shallow waters of the Low Countries...

in New York harbor

New York Harbor

New York Harbor refers to the waterways of the estuary near the mouth of the Hudson River that empty into New York Bay. It is one of the largest natural harbors in the world. Although the U.S. Board of Geographic Names does not use the term, New York Harbor has important historical, governmental,...

that summer, Cleveland had his entire upper jaw removed and replaced with an artificial device, an operation that left no outward scar. The cancer surgery remained secret for another quarter century. Cleveland's aides explained that he had merely had dental work. His vice president little realized how close he came to the presidency that summer.

Adlai Stevenson enjoyed his role as vice president, presiding over the U.S. Senate, "the most august legislative assembly known to men." He won praise for ruling in a dignified, nonpartisan manner. In personal appearance he stood six feet tall and was "of fine personal bearing and uniformly courteous to all." Although he was often a guest at the White House, Stevenson admitted that he was less an adviser to the president than "the neighbor to his counsels." He credited the President with being "courteous at all times" but noted that "no guards were necessary to the preservation of his dignity. No one would have thought of undue familiarity." For his part, President Cleveland snorted that the Vice President had surrounded himself with a coterie of free-silver men dubbed the "Stevenson cabinet." The president even mused that the economy had gotten so bad and the Democratic party so divided that "the logical thing for me to do ... was to resign and hand the Executive branch to Mr. Stevenson," joking that he would try to get his friends jobs in Stevenson's new cabinet.

Presidential campaigns of 1896 and 1900

Stevenson was mentioned as a candidate to succeed Cleveland in 1896. Although he chaired the Illinois delegation to the Democratic National Convention, he gained little support. Stevenson, 60 years old, received a smattering of votes, but the convention was taken by storm by a thirty-six-year-old former representative from Nebraska, William Jennings BryanWilliam Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan was an American politician in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. He was a dominant force in the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, standing three times as its candidate for President of the United States...

, who delivered his fiery "Cross of Gold" speech in favor of a free-silver plank in the platform. Not only did the Democrats repudiate Cleveland by embracing free silver, but they also nominated Bryan for president. Many Cleveland Democrats, including most Democratic newspapers, refused to support Bryan, but Vice President Stevenson loyally endorsed the ticket.

After the 1896 election, Bryan became the titular leader of the Democrats and frontrunner for the nomination in 1900. Much of the newspaper speculation about who would run as the party's vice-presidential candidate centered on Indiana Senator Benjamin Shively. When reporter Arthur Wallace Dunn interviewed Shively at the convention, the senator said he "did not want the glory of a defeat as a vice presidential candidate." Disappointed, Dunn said that he still had to file a story on the vice-presidential nomination, and then added: "I believe I'll write a piece about old Uncle Adlai." Shively responded

- That's a good idea. Stevenson is just the man. There you have it. Uniting the old Cleveland element with the new Bryan Democracy. You've got enough for one story. But say, this is more than a joke. Stevenson is just the man.

For the rest of the day, Dunn heard other favorable remarks about Stevenson, and by that night the former vice president was the leading contender, since no one else was "very anxious to be the tail of what they considered was a forlorn hope

Forlorn hope

A forlorn hope is a band of soldiers or other combatants chosen to take the leading part in a military operation, such as an assault on a defended position, where the risk of casualties is high....

ticket."

The Populists had already nominated the ticket of Bryan and Charles A. Towne

Charles A. Towne

Charles Arnette Towne was an American politician. Born near Pontiac, Michigan, he graduated from the University of Michigan and served in the United States House of Representatives from Minnesota as a Republican in the 54th congress and from New York as a Democrat in the 59th congress.Towne also...

, a pro-silver Republican from Minnesota

Minnesota

Minnesota is a U.S. state located in the Midwestern United States. The twelfth largest state of the U.S., it is the twenty-first most populous, with 5.3 million residents. Minnesota was carved out of the eastern half of the Minnesota Territory and admitted to the Union as the thirty-second state...

, with the tacit understanding that Towne would step aside if the Democrats nominated someone else. Bryan preferred his good friend Towne, but Democrats wanted one of their own, and the regular element of the party felt comfortable with Stevenson. Towne withdrew and campaigned for Bryan and Stevenson. As a result, Stevenson, who had run with Cleveland in 1892, now ran in 1900 with Cleveland's opponent Bryan. Twenty-five years senior to Bryan, Stevenson added age and experience to the ticket. Nevertheless, their effort failed badly against the Republican ticket of McKinley

William McKinley

William McKinley, Jr. was the 25th President of the United States . He is best known for winning fiercely fought elections, while supporting the gold standard and high tariffs; he succeeded in forging a Republican coalition that for the most part dominated national politics until the 1930s...

and Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity...

. (Stevenson's role in the race is perhaps more distinguished by his being the first Vice President to win nomination for that office with a different running mate, after having completed his first term. As of 2008, Republican Charles W. Fairbanks

Charles W. Fairbanks

Charles Warren Fairbanks was a Senator from Indiana and the 26th Vice President of the United States ....

's failure to win a second VP term in 1916 is the only example since.)

Final years

After the 1900 election, Stevenson returned again to private practice in Illinois. He made one last attempt at office in a race for governor of IllinoisGovernor of Illinois

The Governor of Illinois is the chief executive of the State of Illinois and the various agencies and departments over which the officer has jurisdiction, as prescribed in the state constitution. It is a directly elected position, votes being cast by popular suffrage of residents of the state....

in 1908, at age 72, narrowly losing. In 1909 he was brought in by founder Jesse Grant Chapline

Jesse Grant Chapline

Jesse Grant Chapline was an American educator and politician who founded distance learning facility La Salle Extension University in Chicago.-Life and career:...

to aid distance learning school La Salle Extension University

La Salle Extension University

La Salle Extension University , also styled as LaSalle Extension University, was a nationally accredited private university based in Chicago, Illinois. Although the school offered resident educational programs in classes and seminars their primary mode of delivery was by way of distance learning...

. After that, he retired to Bloomington, where his Republican neighbors described him as "windy but amusing." He died in Chicago on June 14, 1914. His body is interred in a family plot in Evergreen Cemetery, Bloomington, Illinois

Bloomington, Illinois

Bloomington is a city in McLean County, Illinois, United States and the county seat. It is adjacent to Normal, Illinois, and is the more populous of the two principal municipalities of the Bloomington-Normal metropolitan area...

.

Stevenson's son, Lewis G. Stevenson, was Illinois secretary of state (1914–1917). Stevenson's grandson Adlai Ewing Stevenson II was Democratic candidate for President of the United States in 1952 and 1956 and Governor of Illinois

Governor of Illinois

The Governor of Illinois is the chief executive of the State of Illinois and the various agencies and departments over which the officer has jurisdiction, as prescribed in the state constitution. It is a directly elected position, votes being cast by popular suffrage of residents of the state....

. His great-grandson, Adlai Ewing Stevenson III

Adlai Stevenson III

Adlai Ewing Stevenson III is an American politician of the Democratic Party. He represented the state of Illinois in the United States Senate from 1970 until 1981.-Education, military service, and early career:...

, was a U.S. senator

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

from Illinois

Illinois

Illinois is the fifth-most populous state of the United States of America, and is often noted for being a microcosm of the entire country. With Chicago in the northeast, small industrial cities and great agricultural productivity in central and northern Illinois, and natural resources like coal,...

from 1970 to 1981 and an unsuccessful candidate for Governor of Illinois

Governor of Illinois

The Governor of Illinois is the chief executive of the State of Illinois and the various agencies and departments over which the officer has jurisdiction, as prescribed in the state constitution. It is a directly elected position, votes being cast by popular suffrage of residents of the state....

in 1982 and 1986.

Legacy

In 1962, Stevenson's alma mater, Centre CollegeCentre College

Centre College is a private liberal arts college in Danville, Kentucky, USA, a community of approximately 16,000 in Boyle County south of Lexington, KY. Centre is an exclusively undergraduate four-year institution. Centre was founded by Presbyterian leaders, with whom it maintains a loose...

(who also gave Stevenson an honorary degree in 1893), built and named a residence hall after Stevenson - Stevenson House - as part of a new campus quadrangle. Stevenson House was renovated in 1995. http://www.centre.edu/campusbuildings/slideshow_quad/index.html