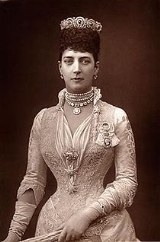

Alexandra of Denmark

Encyclopedia

Alexandra of Denmark was the wife of Edward VII of the United Kingdom. As such, she was Queen consort

of the United Kingdom

and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, from 1901 to 1910.

Her family had been relatively obscure until her father, Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg

, was chosen with the consent of the great power

s to succeed his distant cousin, Frederick VII, to the Danish throne. At the age of sixteen, she was chosen as the future wife of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, the heir-apparent of Queen Victoria. They married eighteen months later in 1863, the same year her father became Christian IX of Denmark and her brother, George

, was appointed King of Greece. She was Princess of Wales

from 1863 to 1901, the longest anyone has ever held that title, and became generally popular; her style of dress and bearing were copied by fashion-conscious women. Although largely excluded from wielding any political power, she unsuccessfully attempted to sway the opinion of British ministers and her husband's family to favour Greek and Danish interests. Her public duties were restricted to uncontroversial involvement in charitable work.

On the death of Queen Victoria in 1901, Albert Edward became King-Emperor

as Edward VII, with Alexandra as Queen-Empress consort. From Edward's death in 1910 until her own death, she was the Queen Mother

, being a queen and the mother of the reigning monarch, George V

, though she was more generally styled Her Majesty Queen Alexandra. She greatly distrusted her nephew, German Emperor Wilhelm II, and supported her son during World War I

, in which Britain and its allies fought Germany.

complex in Copenhagen

. Her father was Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg

and her mother was Princess Louise of Hesse-Cassel. Although she was of royal blood, her family lived a comparatively normal life. They did not possess great wealth; her father's income from an army commission was about £

800 per year and their house was a rent-free grace and favour

property. Occasionally, Hans Christian Andersen

was invited to call and tell the children stories before bedtime.

In 1848, King Christian VIII of Denmark

died and his only son, Frederick

ascended the throne. Frederick was childless, had been through two unsuccessful marriages, and was assumed to be infertile. A succession crisis arose as Frederick ruled in both Denmark

and Schleswig-Holstein

, and the succession rules of each were different. In Holstein, the Salic law

prevented inheritance through the female line, whereas no such restrictions applied in Denmark. Holstein, being predominantly German, proclaimed independence and called in the aid of Prussia

. In 1852, the great power

s called a conference in London

to discuss the Danish succession. An uneasy peace was agreed, which included the provision that Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg would be Frederick's heir in all his dominions and the prior claims of others (who included Christian's own mother-in-law

, brother-in-law and wife) were surrendered.

Prince Christian was given the title Prince of Denmark and his family moved into a new official residence, Bernstorff Palace

. Although the family's status had risen, there was no or little increase in their income and they did not participate in court life at Copenhagen as they refused to meet Frederick's third wife and former mistress, Louise Rasmussen

, because she had an illegitimate child by a previous lover. Alexandra shared a draughty attic bedroom with her sister, Dagmar (later Empress of Russia), made her own clothes and waited at table along with her sisters. At Bernstorff, Alexandra grew into a young woman; she was taught English

by the English chaplain at Copenhagen and was confirmed in Christiansborg Palace

. Alexandra was devout throughout her life, and followed High Church

practice. Alexandra, together with her sister Dagmar, was given swimming lessons by the Swedish pioneer of women's swimming, Nancy Edberg

.

. They enlisted the aid of their daughter, Crown Princess Victoria of Prussia

, in seeking a suitable candidate. Alexandra was not their first choice, since the Danes were at loggerheads with the Prussians over the Schleswig-Holstein Question

and most of the British royal family

's relations were German. Eventually, after rejecting other possibilities, they settled on her as "the only one to be chosen".

On 24 September 1861, Crown Princess Victoria introduced her brother Albert Edward to Alexandra at Speyer

, but it was not until almost a year later on 9 September 1862 (after his affair with Nellie Clifden and the death of his father) that Albert Edward proposed to Alexandra at the Royal Castle of Laeken, the home of his great-uncle, King Leopold I of Belgium

.

A few months later, Alexandra travelled from Denmark to the United Kingdom aboard the royal yacht Victoria and Albert II

and arrived in Gravesend, Kent

, on 7 March 1863. Sir Arthur Sullivan

composed music for her arrival and Alfred Tennyson, the Poet Laureate

, wrote an ode in Alexandra's honour:

The couple were married on 10 March 1863 at St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle

, by Thomas Longley, the Archbishop of Canterbury

. The choice of venue was criticised in the press (as it was outside London, large public crowds would not be able to view the spectacle), by prospective guests (it was awkward to get to and, as the venue was small, some people who had expected invitations were not invited) and the Danes (as only Alexandra's closest relations were invited). The court was still in mourning for Prince Albert, so ladies were restricted to wearing grey, lilac or mauve. As the couple left Windsor for their honeymoon at Osborne House

on the Isle of Wight

, they were cheered by the schoolboys of neighbouring Eton College

, who included Lord Randolph Churchill

.

By the end of the following year, Alexandra's father had ascended the throne of Denmark, her brother George

had become King of the Hellenes, her sister Dagmar was engaged to the Tsarevitch of Russia

, and Alexandra had given birth to her first child. Her father's accession gave rise to further conflict over the fate of Schleswig-Holstein

. The German Confederation

successfully invaded Denmark, reducing the area of Denmark by two-fifths. To the great irritation of Queen Victoria and the Crown Princess of Prussia, Alexandra and Albert Edward supported the Danish side in the war. The Prussia

n conquest of former Danish lands heightened Alexandra's profound dislike of the Germans, a feeling which stayed with her for the rest of her life.

Alexandra's first child, Albert Victor, was born two months premature in early 1864. Alexandra was devoted to her children: "She was in her glory when she could run up to the nursery, put on a flannel apron, wash the children herself and see them asleep in their little beds." Albert Edward and Alexandra had six children in total: Albert Victor, George

, Louise, Victoria

, Maud

and John

. All of Alexandra's children were apparently born prematurely; biographer Richard Hough

thought Alexandra deliberately misled Queen Victoria as to her probable delivery dates, as she did not want the Queen to be present at their births. During the birth of her third child in 1867, the added complication of a bout of rheumatic fever

threatened Alexandra's life, and left her with a permanent limp.

In public, Alexandra was dignified and charming; in private, affectionate and jolly. She enjoyed many social activities, including dancing and ice-skating, and was an expert horsewoman and tandem driver

. She also enjoyed hunting

, to the dismay of Queen Victoria, who asked her to stop, but without success. Even after the birth of her first child, she continued to socialise much as before, which led to some friction between the Queen and the young couple, exacerbated by Alexandra's loathing of Prussians and the Queen's partiality towards them.

Albert Edward and Alexandra visited Ireland in April 1868. After her illness the previous year, she had only just begun to walk again without the aid of two walking sticks, and was already pregnant with her fourth child. The royal couple undertook a six-month tour taking in Austria

Albert Edward and Alexandra visited Ireland in April 1868. After her illness the previous year, she had only just begun to walk again without the aid of two walking sticks, and was already pregnant with her fourth child. The royal couple undertook a six-month tour taking in Austria

, Egypt

and Greece

over 1868 and 1869, which included visits to her brother, King George I of Greece

, to the Crimea

n battlefields and (for her only) to the harem of the Khedive Ismail

. In Turkey

she became the first woman to sit down to dinner with the Sultan (Abdülâziz

).

Albert Edward and Alexandra made Sandringham House

their preferred residence, with Marlborough House

their London base. Biographers agree that their marriage was in many ways a happy one; however, some have asserted that Albert Edward did not give his wife as much attention as she would have liked and that they gradually became estranged, until his attack of typhoid fever

(the disease which was believed to have killed his father) in late 1871 brought about a reconciliation. This is disputed by others, who point out Alexandra's frequent pregnancies throughout this period and use family letters to deny the existence of any serious rift. Nevertheless, Edward was severely criticised from many quarters of society for his apparent lack of interest in her very serious illness with rheumatic fever

. Throughout their marriage Albert Edward continued to keep company with other women, among them the actress Lillie Langtry

; Daisy Greville, Countess of Warwick

; humanitarian Agnes Keyser

; and society matron Alice Keppel

. Most of these were with the full knowledge of Alexandra, who later permitted Alice Keppel to visit the King as he lay dying. Alexandra herself remained faithful throughout her marriage.

An increasing degree of deafness, caused by hereditary otosclerosis

, led to Alexandra's social isolation; she spent more time at home with her children and pets. Her sixth and final pregnancy ended in tragedy when her infant son died after only a day of life. Despite Alexandra's pleas for privacy, Queen Victoria insisted on announcing a period of court mourning, which led to unsympathetic elements of the press to describe the birth as "a wretched abortion" and the funeral arrangements as "sickening mummery".

For eight months over 1875–76, the Prince of Wales was absent from Britain on a tour of India, but to her dismay Alexandra was left behind. The Prince had planned an all-male group and intended to spend much of the time hunting and shooting. During the Prince's tour, one of his friends who was travelling with him, Lord Aylesford

For eight months over 1875–76, the Prince of Wales was absent from Britain on a tour of India, but to her dismay Alexandra was left behind. The Prince had planned an all-male group and intended to spend much of the time hunting and shooting. During the Prince's tour, one of his friends who was travelling with him, Lord Aylesford

, was told by his wife that she was going to leave him for another man: Lord Blandford

, who was himself married. Aylesford was appalled and decided to seek a divorce. Meanwhile, Lord Blandford's brother, Lord Randolph Churchill

, persuaded the lovers against an elopement. Now concerned by the threat of divorce, Lady Aylesford sought to dissuade her husband from proceeding but Lord Aylesford was adamant and refused to reconsider. In an attempt to pressure Lord Aylesford to drop his divorce suit, Lady Aylesford and Lord Randolph Churchill called on Alexandra and told her that if the divorce was to proceed they would subpoena her husband as a witness and implicate him in the scandal. Distressed at their threats, and following the advice of Sir William Knollys

and the Duchess of Teck

, Alexandra informed the Queen, who then wrote to the Prince of Wales. The Prince was incensed. Eventually, the Blandfords and the Aylesfords both separated privately. Although Lord Randolph Churchill later apologised, for years afterwards the Prince of Wales refused to speak to or see him.

Alexandra spent the spring of 1877 in Greece recuperating from a period of ill health and visiting her brother King George of the Hellenes. During the Russo-Turkish War, Alexandra was clearly partial against Turkey and towards Russia, where her sister was married to the Tsarevitch, and she lobbied for a revision of the border between Greece and Turkey in favour of the Greeks. Alexandra and her two sons spent the next three years largely parted from each other's company as the boys were sent on a worldwide cruise as part of their naval and general education. The farewell was very tearful and, as shown by her regular letters, she missed them dreadfully. In 1881, Alexandra and Albert Edward travelled to Saint Petersburg

after the assassination of Alexander II of Russia

, both to represent Britain and so that Alexandra could provide comfort to her sister, who was now the Tsarina

.

Alexandra undertook many public duties; in the words of Queen Victoria, "to spare me the strain and fatigue of functions. She opens bazaars, attends concerts, visits hospitals in my place ... she not only never complains, but endeavours to prove that she has enjoyed what to another would be a tiresome duty." She took a particular interest in the London Hospital, visiting it regularly. Joseph Merrick

, the so-called "Elephant Man", was one of the patients whom she met. Crowds usually cheered Alexandra rapturously, but during a visit to Ireland in 1885, she suffered a rare moment of public hostility when visiting the City of Cork, a hotbed of Irish nationalism

. She and her husband were booed by a crowd of two to three thousand people brandishing sticks and black flags. She smiled her way through the ordeal, which the British press still portrayed in a positive light, describing the crowds as "enthusiastic". As part of the same visit, she received a Doctorate in Music from Trinity College, Dublin

.

The death of her eldest son, Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, in 1892 was a serious blow to Alexandra, and his room and possessions were kept exactly as he had left them, much as those of Prince Albert were left after his death in 1861. She said, "I have buried my angel and with him my happiness." Surviving letters between Alexandra and her children indicate that they were mutually devoted. In 1894, her brother-in-law, Alexander III of Russia

, died and her nephew, Nicholas II of Russia

became Tsar

. Alexandra's widowed sister, the Dowager Empress, leant heavily on her for support; Alexandra slept, prayed, and stayed beside her sister for the next two weeks until Alexander's burial.

left on an extensive tour of the empire, leaving their young children in the care of Alexandra and Edward, who doted on their grandchildren. On George's return, preparations for the coronation

of Edward and Alexandra were well in hand. Just a few days before the scheduled coronation in June 1902, however, Edward became seriously ill with an appendix abscess or appendicitis

. Alexandra deputised for him at a military parade, and attended the Royal Ascot races

without him, in an attempt to prevent public alarm. Eventually, the coronation had to be postponed and Edward had an operation performed by Frederick Treves

of the London Hospital to drain the infected appendix. After his recovery, Alexandra and Edward were crowned together in August: he by the Archbishop of Canterbury

, Frederick Temple

, and she by the Archbishop of York

, William Dalrymple Maclagan

.

Despite now being queen, Alexandra's duties changed little, and she kept many of the same retainers. Alexandra's Woman of the Bedchamber

, Charlotte Knollys

, served Alexandra loyally for many years. On 10 December 1903, Charlotte, the daughter of Sir William Knollys, woke to find her bedroom full of smoke. She roused Alexandra and shepherded her to safety. In the words of Grand Duchess Augusta of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, "We must give credit to old Charlotte for really saving [Alexandra's] life."

Alexandra again looked after her grandchildren when George and Mary went on a second tour, this time to British India, over the winter of 1905–06. Her father, King Christian IX of Denmark, died that January. Eager to retain their family links, to both each other and to Denmark, in 1907 Alexandra and her sister, the Dowager Empress of Russia, purchased a villa north of Copenhagen, Hvidøre, as a private getaway.

Biographers have asserted that Alexandra was denied access to the King's briefing papers and excluded from some of the King's foreign tours to prevent her meddling in diplomatic matters. She was deeply distrustful of Germans, and invariably opposed anything that favoured German expansion or interests. For example, in 1890 Alexandra wrote a memorandum, distributed to senior British ministers and military personnel, warning against the planned exchange of the British North Sea

island of Heligoland

for the German colony of Zanzibar

, pointing out Heligoland's strategic significance and that it could be used either by Germany to launch an attack, or by Britain to contain German aggression. Despite this, the exchange went ahead anyway. The Germans fortified the island and, in the words of Robert Ensor

and as Alexandra had predicted, it "became the keystone of Germany's maritime position for offence as well as for defence". The Frankfurter Zeitung

was outspoken in its condemnation of Alexandra and her sister, the Dowager Empress of Russia, saying that the pair were "the centre of the international anti-German conspiracy". She despised and distrusted her nephew, Wilhelm II of Germany, calling him in 1900 "inwardly our enemy".

In 1910, Alexandra became the first queen consort to visit the British House of Commons

during a debate. In a remarkable departure from precedent, for two hours she sat in the Ladies' Gallery overlooking the chamber while the Parliament Bill

, a bill to reform the role of the House of Lords

, was debated. Privately, Alexandra disagreed with the bill. Shortly afterward, she left to visit her brother, King George I of Greece, in Corfu

. While there, she received news that King Edward was seriously ill. Alexandra returned at once and arrived just the day before her husband died. In his last hours, she personally administered oxygen from a gas cylinder to help him breathe. She told Frederick Ponsonby

, "I feel as if I had been turned into stone, unable to cry, unable to grasp the meaning of it all." Later that year, she moved out of Buckingham Palace

to Marlborough House

, but she retained possession of Sandringham. The new king, Alexandra's son George

, soon faced a decision over the Parliament Bill. Despite her personal views, Alexandra supported the King's decision to help force the bill through Parliament at the Prime Minister

's request but against the wishes of the House of Lords when the reforming party won elections to the House of Commons.

Alexandra did not attend her son's coronation in 1911 since it was not customary for a crowned queen to attend the coronation of another king or queen, but otherwise continued the public side of her life, devoting time to her charitable causes. One such cause included Alexandra Rose Day

Alexandra did not attend her son's coronation in 1911 since it was not customary for a crowned queen to attend the coronation of another king or queen, but otherwise continued the public side of her life, devoting time to her charitable causes. One such cause included Alexandra Rose Day

, where artificial roses made by the disabled were sold in aid of hospitals by women volunteers. During the First World War

, the custom of hanging the banners of foreign princes invested with Britain's highest order of knighthood, the Order of the Garter

, in St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle

, came under criticism, as the German members of the Order were fighting against Britain. Alexandra joined calls to "have down those hateful German banners". Driven by public opinion, but against his own wishes, the King had the banners removed but to Alexandra's dismay he had down not only "those vile Prussian banners" but also those of her Hessian relations who were, in her opinion, "simply soldiers or vassals under that brutal German Emperor's orders". On 17 September 1916, she was at Sandringham during a Zeppelin

air raid, but far worse was to befall other members of her family. In Russia, her nephew Tsar Nicholas II

was overthrown and he, his wife and children were killed by revolutionaries. Her sister the Dowager Empress was rescued from Russia in 1919 by and brought to England where she lived for some time with Alexandra.

Alexandra retained a youthful appearance into her senior years, but during the war her age caught up with her. She took to wearing elaborate veils and heavy makeup, which was described by gossips as having her face "enamelled". She made no more trips abroad, and suffered increasing ill-health. In 1920, a blood vessel in her eye burst, leaving her with temporary partial blindness. Towards the end of her life, her memory and speech became impaired. She died on 20 November 1925 at Sandringham

after suffering a heart attack

and was buried in an elaborate tomb next to her husband in St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle

.

After Alexandra married the Prince of Wales in 1863, a new park and "Palace of the People", a huge public exhibition and arts centre being built on a hilltop overlooking north London, were renamed the Alexandra Palace

After Alexandra married the Prince of Wales in 1863, a new park and "Palace of the People", a huge public exhibition and arts centre being built on a hilltop overlooking north London, were renamed the Alexandra Palace

and park to commemorate her.

The Queen Alexandra Memorial by Alfred Gilbert

was unveiled on Alexandra Rose Day

8 June 1932 at Marlborough Gate, London. An ode in her memory, "So many true princesses who have gone"

, composed by the then Master of the King's Musick Sir Edward Elgar

to words by the Poet Laureate

John Masefield

, was sung at the unveiling and conducted by the composer.

Alexandra was highly popular with the British public. Unlike her husband and mother-in-law, she was not castigated by the press. Funds that she helped to collect were used to buy a river launch, called Alexandra, to ferry the wounded during the Sudan campaign

, and to fit out a hospital ship, named The Princess of Wales, to bring back wounded from the Boer War

. During the Boer War, Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service, later renamed Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps

, was founded under Royal Warrant.

She had little understanding of money. The management of her finances was left in the hands of her loyal comptroller

, Sir Dighton Probyn VC

, who undertook a similar role for her husband. In the words of her grandson, Edward VIII

(later the Duke of Windsor), "Her generosity was a source of embarrassment to her financial advisers. Whenever she received a letter soliciting money, a cheque would be sent by the next post, regardless of the authenticity of the mendicant and without having the case investigated." Though she was not always extravagant (she had her old stockings darned for re-use and her old dresses were recycled as furniture covers), she would dismiss protests about her heavy spending with a wave of a hand or by claiming that she had not heard.

She hid a small scar on her neck, which was likely the result of a childhood operation, by wearing choker

necklaces and high necklines, setting fashions which were adopted for fifty years. Alexandra's effect on fashion was so profound that society ladies even copied her limping gait, after her serious illness in 1867 left her with a stiff leg. She used predominantly the London fashion houses; her favourite was Redfern's

, but she shopped occasionally at Doucet

and Fromont of Paris.

Queen Alexandra has been portrayed on British television by Deborah Grant and Helen Ryan in Edward the Seventh, Ann Firbank in Lillie, Maggie Smith

in All the King's Men

, and Bibi Andersson

in The Lost Prince

. Helen Ryan also portrayed her in the 1980 film The Elephant Man

. In a 1980 stage play by Royce Ryton

, Motherdear, she was portrayed by Margaret Lockwood in her last acting role.

, Lady of the Imperial Order of the Crown of India

, and Lady of Justice of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem

.

impaled with the arms of her father, King Christian IX of Denmark

. The shield is surmounted by the imperial crown, and supported by the crowned lion of England and a wild man or savage from the Danish royal arms

.

|-

|-

Queen consort

A queen consort is the wife of a reigning king. A queen consort usually shares her husband's rank and holds the feminine equivalent of the king's monarchical titles. Historically, queens consort do not share the king regnant's political and military powers. Most queens in history were queens consort...

of the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, from 1901 to 1910.

Her family had been relatively obscure until her father, Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg

Christian IX of Denmark

Christian IX was King of Denmark from 16 November 1863 to 29 January 1906.Growing up as a prince of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, a junior branch of the House of Oldenburg which had ruled Denmark since 1448, Christian was originally not in the immediate line of succession to the Danish...

, was chosen with the consent of the great power

Great power

A great power is a nation or state that has the ability to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength and diplomatic and cultural influence which may cause small powers to consider the opinions of great powers before taking actions...

s to succeed his distant cousin, Frederick VII, to the Danish throne. At the age of sixteen, she was chosen as the future wife of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, the heir-apparent of Queen Victoria. They married eighteen months later in 1863, the same year her father became Christian IX of Denmark and her brother, George

George I of Greece

George I was King of Greece from 1863 to 1913. Originally a Danish prince, George was only 17 years old when he was elected king by the Greek National Assembly, which had deposed the former king Otto. His nomination was both suggested and supported by the Great Powers...

, was appointed King of Greece. She was Princess of Wales

Princess of Wales

Princess of Wales is a British courtesy title held by the wife of The Prince of Wales since the first "English" Prince of Wales in 1283.Although there have been considerably more than ten male heirs to the throne, there have been only ten Princesses of Wales. The majority of Princes of Wales...

from 1863 to 1901, the longest anyone has ever held that title, and became generally popular; her style of dress and bearing were copied by fashion-conscious women. Although largely excluded from wielding any political power, she unsuccessfully attempted to sway the opinion of British ministers and her husband's family to favour Greek and Danish interests. Her public duties were restricted to uncontroversial involvement in charitable work.

On the death of Queen Victoria in 1901, Albert Edward became King-Emperor

King-Emperor

A king-emperor, the female equivalent being queen-empress, is a sovereign ruler who is simultaneously a king of one territory and emperor of another...

as Edward VII, with Alexandra as Queen-Empress consort. From Edward's death in 1910 until her own death, she was the Queen Mother

Queen mother

Queen Mother is a title or position reserved for a widowed queen consort whose son or daughter from that marriage is the reigning monarch. The term has been used in English since at least 1577...

, being a queen and the mother of the reigning monarch, George V

George V

George V was king of the United Kingdom and its dominions from 1910 to 1936.George V or similar terms may also refer to:-People:* George V of Georgia * George V of Imereti * George V of Hanover...

, though she was more generally styled Her Majesty Queen Alexandra. She greatly distrusted her nephew, German Emperor Wilhelm II, and supported her son during World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, in which Britain and its allies fought Germany.

Early life

Princess Alexandra Caroline Marie Charlotte Louise Julia, or "Alix", as her immediate family knew her, was born at the Yellow Palace, an 18th-century town house at 18 Amaliegade, right next to the Amalienborg PalaceAmalienborg Palace

Amalienborg Palace is the winter home of the Danish royal family, and is located in Copenhagen, Denmark. It consists of four identical classicizing palace façades with rococo interiors around an octagonal courtyard ; in the centre of the square is a monumental equestrian statue of Amalienborg's...

complex in Copenhagen

Copenhagen

Copenhagen is the capital and largest city of Denmark, with an urban population of 1,199,224 and a metropolitan population of 1,930,260 . With the completion of the transnational Øresund Bridge in 2000, Copenhagen has become the centre of the increasingly integrating Øresund Region...

. Her father was Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg

Christian IX of Denmark

Christian IX was King of Denmark from 16 November 1863 to 29 January 1906.Growing up as a prince of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, a junior branch of the House of Oldenburg which had ruled Denmark since 1448, Christian was originally not in the immediate line of succession to the Danish...

and her mother was Princess Louise of Hesse-Cassel. Although she was of royal blood, her family lived a comparatively normal life. They did not possess great wealth; her father's income from an army commission was about £

Pound sterling

The pound sterling , commonly called the pound, is the official currency of the United Kingdom, its Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, British Antarctic Territory and Tristan da Cunha. It is subdivided into 100 pence...

800 per year and their house was a rent-free grace and favour

Grace and favour

A grace and favour home is a residential property owned by a monarch by virtue of their position as head of state and leased rent-free to persons as part of an employment package or in gratitude for past services rendered....

property. Occasionally, Hans Christian Andersen

Hans Christian Andersen

Hans Christian Andersen was a Danish author, fairy tale writer, and poet noted for his children's stories. These include "The Steadfast Tin Soldier," "The Snow Queen," "The Little Mermaid," "Thumbelina," "The Little Match Girl," and "The Ugly Duckling."...

was invited to call and tell the children stories before bedtime.

In 1848, King Christian VIII of Denmark

Christian VIII of Denmark

Christian VIII , was king of Denmark from 1839 to 1848 and, as Christian Frederick, king of Norway in 1814. He was the eldest son of Hereditary Prince Frederick of Denmark and Norway and Sophia Frederica of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, born in 1786 at Christiansborg Palace in Copenhagen...

died and his only son, Frederick

Frederick VII of Denmark

Frederick VII was a King of Denmark. He reigned from 1848 until his death. He was the last Danish monarch of the older Royal branch of the House of Oldenburg and also the last king of Denmark to rule as an absolute monarch...

ascended the throne. Frederick was childless, had been through two unsuccessful marriages, and was assumed to be infertile. A succession crisis arose as Frederick ruled in both Denmark

Denmark

Denmark is a Scandinavian country in Northern Europe. The countries of Denmark and Greenland, as well as the Faroe Islands, constitute the Kingdom of Denmark . It is the southernmost of the Nordic countries, southwest of Sweden and south of Norway, and bordered to the south by Germany. Denmark...

and Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein is the northernmost of the sixteen states of Germany, comprising most of the historical duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of Schleswig...

, and the succession rules of each were different. In Holstein, the Salic law

Salic law

Salic law was a body of traditional law codified for governing the Salian Franks in the early Middle Ages during the reign of King Clovis I in the 6th century...

prevented inheritance through the female line, whereas no such restrictions applied in Denmark. Holstein, being predominantly German, proclaimed independence and called in the aid of Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

. In 1852, the great power

Great power

A great power is a nation or state that has the ability to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength and diplomatic and cultural influence which may cause small powers to consider the opinions of great powers before taking actions...

s called a conference in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

to discuss the Danish succession. An uneasy peace was agreed, which included the provision that Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg would be Frederick's heir in all his dominions and the prior claims of others (who included Christian's own mother-in-law

Princess Louise Charlotte of Denmark

Princess Louise Charlotte of Denmark was a princess of Denmark.She was born in Christiansborg Palace to Hereditary Prince Frederick of Denmark and Norway and Sophia Frederica of Mecklenburg-Schwerin , Princess and Duchess of Mecklenburg-Schwerin.-Marriage:On 10 November 1810 in Amalienborg Palace...

, brother-in-law and wife) were surrendered.

Prince Christian was given the title Prince of Denmark and his family moved into a new official residence, Bernstorff Palace

Bernstorff Palace

Bernstorff Palace, Danish: Bernstorff Slot, in Gentofte, Copenhagen, Denmark, was built in the middle of the 18th century for Foreign Minister Johann Hartwig Ernst, Count von Bernstorff. It remained in the possession of the Bernstorff family until 1812. In 1842 it was bought by Christian VIII...

. Although the family's status had risen, there was no or little increase in their income and they did not participate in court life at Copenhagen as they refused to meet Frederick's third wife and former mistress, Louise Rasmussen

Louise Rasmussen

Louise Christine Rasmussen, also known as Countess Danner , was a Danish Ballet dancer and stage actor. She was the mistress and later the morganatic spouse of King Frederick VII of Denmark...

, because she had an illegitimate child by a previous lover. Alexandra shared a draughty attic bedroom with her sister, Dagmar (later Empress of Russia), made her own clothes and waited at table along with her sisters. At Bernstorff, Alexandra grew into a young woman; she was taught English

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

by the English chaplain at Copenhagen and was confirmed in Christiansborg Palace

Christiansborg Palace

Christiansborg Palace, , on the islet of Slotsholmen in central Copenhagen, is the seat of the Folketing , the Danish Prime Minister's Office and the Danish Supreme Court...

. Alexandra was devout throughout her life, and followed High Church

High church

The term "High Church" refers to beliefs and practices of ecclesiology, liturgy and theology, generally with an emphasis on formality, and resistance to "modernization." Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term has traditionally been principally associated with the...

practice. Alexandra, together with her sister Dagmar, was given swimming lessons by the Swedish pioneer of women's swimming, Nancy Edberg

Nancy Edberg

Nancy Fredrika Augusta Edberg , was a Swedish swimmer, swimming instructor and bath house director. She was the first Swedish woman in these fields. Edberg was a pioneer in making the art of swimming and ice skating accepted for women in Sweden- Biography :Nancy Edberg was taught to swim by her...

.

Marriage and family

Queen Victoria and her husband, Prince Albert, were already concerned with finding a bride for their son and heir, Albert Edward, the Prince of WalesPrince of Wales

Prince of Wales is a title traditionally granted to the heir apparent to the reigning monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the 15 other independent Commonwealth realms...

. They enlisted the aid of their daughter, Crown Princess Victoria of Prussia

Victoria, Princess Royal

The Princess Victoria, Princess Royal was the eldest child of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and Prince Albert. She was created Princess Royal of the United Kingdom in 1841. She became German Empress and Queen of Prussia by marriage to German Emperor Frederick III...

, in seeking a suitable candidate. Alexandra was not their first choice, since the Danes were at loggerheads with the Prussians over the Schleswig-Holstein Question

Schleswig-Holstein Question

The Schleswig-Holstein Question was a complex of diplomatic and other issues arising in the 19th century from the relations of two duchies, Schleswig and Holstein , to the Danish crown and to the German Confederation....

and most of the British royal family

British Royal Family

The British Royal Family is the group of close relatives of the monarch of the United Kingdom. The term is also commonly applied to the same group of people as the relations of the monarch in her or his role as sovereign of any of the other Commonwealth realms, thus sometimes at variance with...

's relations were German. Eventually, after rejecting other possibilities, they settled on her as "the only one to be chosen".

On 24 September 1861, Crown Princess Victoria introduced her brother Albert Edward to Alexandra at Speyer

Speyer

Speyer is a city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany with approximately 50,000 inhabitants. Located beside the river Rhine, Speyer is 25 km south of Ludwigshafen and Mannheim. Founded by the Romans, it is one of Germany's oldest cities...

, but it was not until almost a year later on 9 September 1862 (after his affair with Nellie Clifden and the death of his father) that Albert Edward proposed to Alexandra at the Royal Castle of Laeken, the home of his great-uncle, King Leopold I of Belgium

Leopold I of Belgium

Leopold I was from 21 July 1831 the first King of the Belgians, following Belgium's independence from the Netherlands. He was the founder of the Belgian line of the House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha...

.

A few months later, Alexandra travelled from Denmark to the United Kingdom aboard the royal yacht Victoria and Albert II

HMY Victoria and Albert II

HMY Victoria and Albert, a 360 foot steamer launched 16 January 1855, was a Royal Yacht of the Sovereign of the United Kingdom until 1900, owned and operated by the Royal Navy. She displaced 2,470 tons, and could make 15 knots on her paddles...

and arrived in Gravesend, Kent

Gravesend, Kent

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, on the south bank of the Thames, opposite Tilbury in Essex. It is the administrative town of the Borough of Gravesham and, because of its geographical position, has always had an important role to play in the history and communications of this part of...

, on 7 March 1863. Sir Arthur Sullivan

Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan MVO was an English composer of Irish and Italian ancestry. He is best known for his series of 14 operatic collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including such enduring works as H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance and The Mikado...

composed music for her arrival and Alfred Tennyson, the Poet Laureate

Poet Laureate

A poet laureate is a poet officially appointed by a government and is often expected to compose poems for state occasions and other government events...

, wrote an ode in Alexandra's honour:

The couple were married on 10 March 1863 at St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle

St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle

St George's Chapel is the place of worship at Windsor Castle in England, United Kingdom. It is both a royal peculiar and the chapel of the Order of the Garter...

, by Thomas Longley, the Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

. The choice of venue was criticised in the press (as it was outside London, large public crowds would not be able to view the spectacle), by prospective guests (it was awkward to get to and, as the venue was small, some people who had expected invitations were not invited) and the Danes (as only Alexandra's closest relations were invited). The court was still in mourning for Prince Albert, so ladies were restricted to wearing grey, lilac or mauve. As the couple left Windsor for their honeymoon at Osborne House

Osborne House

Osborne House is a former royal residence in East Cowes, Isle of Wight, UK. The house was built between 1845 and 1851 for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as a summer home and rural retreat....

on the Isle of Wight

Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight is a county and the largest island of England, located in the English Channel, on average about 2–4 miles off the south coast of the county of Hampshire, separated from the mainland by a strait called the Solent...

, they were cheered by the schoolboys of neighbouring Eton College

Eton College

Eton College, often referred to simply as Eton, is a British independent school for boys aged 13 to 18. It was founded in 1440 by King Henry VI as "The King's College of Our Lady of Eton besides Wyndsor"....

, who included Lord Randolph Churchill

Lord Randolph Churchill

Lord Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill MP was a British statesman. He was the third son of the 7th Duke of Marlborough and his wife Lady Frances Anne Emily Vane , daughter of the 3rd Marquess of Londonderry...

.

By the end of the following year, Alexandra's father had ascended the throne of Denmark, her brother George

George I of Greece

George I was King of Greece from 1863 to 1913. Originally a Danish prince, George was only 17 years old when he was elected king by the Greek National Assembly, which had deposed the former king Otto. His nomination was both suggested and supported by the Great Powers...

had become King of the Hellenes, her sister Dagmar was engaged to the Tsarevitch of Russia

Grand Duke Nicholas Alexandrovich of Russia

For the son of Alexander III, who succeeded his father on the throne in 1894, see Nicholas II of Russia.Nicholas Alexandrovich Romanov , full title: Heir, Tsesarevich and Grand Duke of Russia was Tsesarevich —the heir apparent—of Imperial Russia from 2 March 1855 until...

, and Alexandra had given birth to her first child. Her father's accession gave rise to further conflict over the fate of Schleswig-Holstein

Second War of Schleswig

The Second Schleswig War was the second military conflict as a result of the Schleswig-Holstein Question. It began on 1 February 1864, when Prussian forces crossed the border into Schleswig.Denmark fought Prussia and Austria...

. The German Confederation

German Confederation

The German Confederation was the loose association of Central European states created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 to coordinate the economies of separate German-speaking countries. It acted as a buffer between the powerful states of Austria and Prussia...

successfully invaded Denmark, reducing the area of Denmark by two-fifths. To the great irritation of Queen Victoria and the Crown Princess of Prussia, Alexandra and Albert Edward supported the Danish side in the war. The Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

n conquest of former Danish lands heightened Alexandra's profound dislike of the Germans, a feeling which stayed with her for the rest of her life.

Alexandra's first child, Albert Victor, was born two months premature in early 1864. Alexandra was devoted to her children: "She was in her glory when she could run up to the nursery, put on a flannel apron, wash the children herself and see them asleep in their little beds." Albert Edward and Alexandra had six children in total: Albert Victor, George

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

, Louise, Victoria

Princess Victoria Alexandra of the United Kingdom

-Titles and styles:*6 July 1868 – 22 January 1901: Her Royal Highness Princess Victoria of Wales*22 January 1901 – 3 December 1935: Her Royal Highness The Princess Victoria-Honours:*Imperial Order of the Crown of India, 6 August 1887...

, Maud

Maud of Wales

Princess Maud of Wales was Queen of Norway as spouse of King Haakon VII. She was a member of the British Royal Family as the youngest daughter of Edward VII and Alexandra of Denmark and granddaughter of Queen Victoria and also of Christian IX of Denmark. She was the younger sister of George V...

and John

Prince Alexander John of Wales

Prince Alexander John Charles Albert of Wales was the youngest son and sixth child of Prince Albert Edward, Prince of Wales and his wife Princess Alexandra, Princess of Wales and grandson of Queen Victoria and Christian IX of Denmark.-Life:Prince Alexander John Charles Albert of Wales was born...

. All of Alexandra's children were apparently born prematurely; biographer Richard Hough

Richard Hough

Richard Alexander Hough was a British author and historian specializing in maritime history.-Personal life:Hough married the author Charlotte Woodyadd, who he had met when they were pupils at Frensham Heights School, and they had five children including the author Deborah Moggach.-Literary...

thought Alexandra deliberately misled Queen Victoria as to her probable delivery dates, as she did not want the Queen to be present at their births. During the birth of her third child in 1867, the added complication of a bout of rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever is an inflammatory disease that occurs following a Streptococcus pyogenes infection, such as strep throat or scarlet fever. Believed to be caused by antibody cross-reactivity that can involve the heart, joints, skin, and brain, the illness typically develops two to three weeks after...

threatened Alexandra's life, and left her with a permanent limp.

In public, Alexandra was dignified and charming; in private, affectionate and jolly. She enjoyed many social activities, including dancing and ice-skating, and was an expert horsewoman and tandem driver

Combined driving

Combined driving also known as Horse Driving Trials is an equestrian sport involving carriage driving. In this discipline the driver sits on a vehicle drawn by a single horse, a pair or a team of four. The sport has three phases: Dressage, Cross-country Marathon and Obstacle Cone Driving and is...

. She also enjoyed hunting

Hunting

Hunting is the practice of pursuing any living thing, usually wildlife, for food, recreation, or trade. In present-day use, the term refers to lawful hunting, as distinguished from poaching, which is the killing, trapping or capture of the hunted species contrary to applicable law...

, to the dismay of Queen Victoria, who asked her to stop, but without success. Even after the birth of her first child, she continued to socialise much as before, which led to some friction between the Queen and the young couple, exacerbated by Alexandra's loathing of Prussians and the Queen's partiality towards them.

Princess of Wales

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

, Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

and Greece

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

over 1868 and 1869, which included visits to her brother, King George I of Greece

George I of Greece

George I was King of Greece from 1863 to 1913. Originally a Danish prince, George was only 17 years old when he was elected king by the Greek National Assembly, which had deposed the former king Otto. His nomination was both suggested and supported by the Great Powers...

, to the Crimea

Crimea

Crimea , or the Autonomous Republic of Crimea , is a sub-national unit, an autonomous republic, of Ukraine. It is located on the northern coast of the Black Sea, occupying a peninsula of the same name...

n battlefields and (for her only) to the harem of the Khedive Ismail

Isma'il Pasha

Isma'il Pasha , known as Ismail the Magnificent , was the Khedive of Egypt and Sudan from 1863 to 1879, when he was removed at the behest of the United Kingdom...

. In Turkey

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

she became the first woman to sit down to dinner with the Sultan (Abdülâziz

Abdülâziz

Abdülaziz I or Abd Al-Aziz, His Imperial Majesty was the 32nd Sultan of the Ottoman Empire and reigned between 25 June 1861 and 30 May 1876...

).

Albert Edward and Alexandra made Sandringham House

Sandringham House

Sandringham House is a country house on of land near the village of Sandringham in Norfolk, England. The house is privately owned by the British Royal Family and is located on the royal Sandringham Estate, which lies within the Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.-History and current...

their preferred residence, with Marlborough House

Marlborough House

Marlborough House is a mansion in Westminster, London, in Pall Mall just east of St James's Palace. It was built for Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough, the favourite and confidante of Queen Anne. The Duchess wanted her new house to be "strong, plain and convenient and good"...

their London base. Biographers agree that their marriage was in many ways a happy one; however, some have asserted that Albert Edward did not give his wife as much attention as she would have liked and that they gradually became estranged, until his attack of typhoid fever

Typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as Typhoid, is a common worldwide bacterial disease, transmitted by the ingestion of food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person, which contain the bacterium Salmonella enterica, serovar Typhi...

(the disease which was believed to have killed his father) in late 1871 brought about a reconciliation. This is disputed by others, who point out Alexandra's frequent pregnancies throughout this period and use family letters to deny the existence of any serious rift. Nevertheless, Edward was severely criticised from many quarters of society for his apparent lack of interest in her very serious illness with rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever is an inflammatory disease that occurs following a Streptococcus pyogenes infection, such as strep throat or scarlet fever. Believed to be caused by antibody cross-reactivity that can involve the heart, joints, skin, and brain, the illness typically develops two to three weeks after...

. Throughout their marriage Albert Edward continued to keep company with other women, among them the actress Lillie Langtry

Lillie Langtry

Lillie Langtry , usually spelled Lily Langtry when she was in the U.S., born Emilie Charlotte Le Breton, was a British actress born on the island of Jersey...

; Daisy Greville, Countess of Warwick

Daisy Greville, Countess of Warwick

Frances Evelyn "Daisy" Greville, Countess of Warwick was a society beauty, and mistress to King Edward VII.-Family:...

; humanitarian Agnes Keyser

Agnes Keyser

Agnes Keyser was the wealthy daughter of a Stock Exchange member, a humanitarian, courtesan and longtime mistress to Edward VII of the United Kingdom. Of all of Edward VII's mistresses, with the exception of socialite Jennie Jerome, Keyser was the best accepted within royal circles, to include...

; and society matron Alice Keppel

Alice Keppel

Alice Frederica Keppel, née Edmonstone was a British socialite and the most famous mistress of Edward VII, the eldest son of Queen Victoria. Her formal style after marriage was The Hon. Mrs George Keppel. Her daughter, Violet Trefusis, was the lover of poet Vita Sackville-West...

. Most of these were with the full knowledge of Alexandra, who later permitted Alice Keppel to visit the King as he lay dying. Alexandra herself remained faithful throughout her marriage.

An increasing degree of deafness, caused by hereditary otosclerosis

Otosclerosis

Otosclerosis is an abnormal growth of bone near the middle ear. It can result in hearing loss.-Clinical description:Otosclerosis can result in conductive and/or sensorineural hearing loss...

, led to Alexandra's social isolation; she spent more time at home with her children and pets. Her sixth and final pregnancy ended in tragedy when her infant son died after only a day of life. Despite Alexandra's pleas for privacy, Queen Victoria insisted on announcing a period of court mourning, which led to unsympathetic elements of the press to describe the birth as "a wretched abortion" and the funeral arrangements as "sickening mummery".

Earl of Aylesford

Earl of Aylesford, in the County of Kent, is a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1714 for the lawyer and politician Heneage Finch, 1st Baron Guernsey. He had already been created Baron Guernsey in the Peerage of England in 1703...

, was told by his wife that she was going to leave him for another man: Lord Blandford

George Spencer-Churchill, 8th Duke of Marlborough

George Charles Spencer-Churchill, 8th Duke of Marlborough DL , styled Earl of Sunderland until 1857 and Marquess of Blandford between 1857 and 1883, was a British peer.-Background and education:...

, who was himself married. Aylesford was appalled and decided to seek a divorce. Meanwhile, Lord Blandford's brother, Lord Randolph Churchill

Lord Randolph Churchill

Lord Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill MP was a British statesman. He was the third son of the 7th Duke of Marlborough and his wife Lady Frances Anne Emily Vane , daughter of the 3rd Marquess of Londonderry...

, persuaded the lovers against an elopement. Now concerned by the threat of divorce, Lady Aylesford sought to dissuade her husband from proceeding but Lord Aylesford was adamant and refused to reconsider. In an attempt to pressure Lord Aylesford to drop his divorce suit, Lady Aylesford and Lord Randolph Churchill called on Alexandra and told her that if the divorce was to proceed they would subpoena her husband as a witness and implicate him in the scandal. Distressed at their threats, and following the advice of Sir William Knollys

Knollys (family)

Knollys, the name of an English family descended from Sir Thomas Knollys , Lord Mayor of London. The first distinguished member of the family was Sir Francis Knollys , English statesman, son of Sir Robert Knollys, or Knolles , a courtier in the service and favour of Henry VII and Henry VIII...

and the Duchess of Teck

Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge

Princess Mary Adelaide Wilhelmina Elizabeth of Cambridge was a member of the British Royal Family, a granddaughter of George III, and great-grandmother of Elizabeth II. She held the title of Duchess of Teck through marriage.Mary Adelaide is remembered as the mother of Queen Mary, the consort of...

, Alexandra informed the Queen, who then wrote to the Prince of Wales. The Prince was incensed. Eventually, the Blandfords and the Aylesfords both separated privately. Although Lord Randolph Churchill later apologised, for years afterwards the Prince of Wales refused to speak to or see him.

Alexandra spent the spring of 1877 in Greece recuperating from a period of ill health and visiting her brother King George of the Hellenes. During the Russo-Turkish War, Alexandra was clearly partial against Turkey and towards Russia, where her sister was married to the Tsarevitch, and she lobbied for a revision of the border between Greece and Turkey in favour of the Greeks. Alexandra and her two sons spent the next three years largely parted from each other's company as the boys were sent on a worldwide cruise as part of their naval and general education. The farewell was very tearful and, as shown by her regular letters, she missed them dreadfully. In 1881, Alexandra and Albert Edward travelled to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg is a city and a federal subject of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea...

after the assassination of Alexander II of Russia

Alexander II of Russia

Alexander II , also known as Alexander the Liberator was the Emperor of the Russian Empire from 3 March 1855 until his assassination in 1881...

, both to represent Britain and so that Alexandra could provide comfort to her sister, who was now the Tsarina

Tsaritsa

Tsaritsa , formerly spelled czaritsa , is the title of a female autocratic ruler of Bulgaria or Russia, or the title of a tsar's wife....

.

Alexandra undertook many public duties; in the words of Queen Victoria, "to spare me the strain and fatigue of functions. She opens bazaars, attends concerts, visits hospitals in my place ... she not only never complains, but endeavours to prove that she has enjoyed what to another would be a tiresome duty." She took a particular interest in the London Hospital, visiting it regularly. Joseph Merrick

Joseph Merrick

Joseph Carey Merrick , sometimes incorrectly referred to as John Merrick, was an English man with severe deformities who was exhibited as a human curiosity named the Elephant Man. He became well known in London society after he went to live at the London Hospital...

, the so-called "Elephant Man", was one of the patients whom she met. Crowds usually cheered Alexandra rapturously, but during a visit to Ireland in 1885, she suffered a rare moment of public hostility when visiting the City of Cork, a hotbed of Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism manifests itself in political and social movements and in sentiment inspired by a love for Irish culture, language and history, and as a sense of pride in Ireland and in the Irish people...

. She and her husband were booed by a crowd of two to three thousand people brandishing sticks and black flags. She smiled her way through the ordeal, which the British press still portrayed in a positive light, describing the crowds as "enthusiastic". As part of the same visit, she received a Doctorate in Music from Trinity College, Dublin

Trinity College, Dublin

Trinity College, Dublin , formally known as the College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity of Queen Elizabeth near Dublin, was founded in 1592 by letters patent from Queen Elizabeth I as the "mother of a university", Extracts from Letters Patent of Elizabeth I, 1592: "...we...found and...

.

The death of her eldest son, Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, in 1892 was a serious blow to Alexandra, and his room and possessions were kept exactly as he had left them, much as those of Prince Albert were left after his death in 1861. She said, "I have buried my angel and with him my happiness." Surviving letters between Alexandra and her children indicate that they were mutually devoted. In 1894, her brother-in-law, Alexander III of Russia

Alexander III of Russia

Alexander Alexandrovich Romanov , historically remembered as Alexander III or Alexander the Peacemaker reigned as Emperor of Russia from until his death on .-Disposition:...

, died and her nephew, Nicholas II of Russia

Nicholas II of Russia

Nicholas II was the last Emperor of Russia, Grand Prince of Finland, and titular King of Poland. His official short title was Nicholas II, Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias and he is known as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer by the Russian Orthodox Church.Nicholas II ruled from 1894 until...

became Tsar

Tsar

Tsar is a title used to designate certain European Slavic monarchs or supreme rulers. As a system of government in the Tsardom of Russia and Russian Empire, it is known as Tsarist autocracy, or Tsarism...

. Alexandra's widowed sister, the Dowager Empress, leant heavily on her for support; Alexandra slept, prayed, and stayed beside her sister for the next two weeks until Alexander's burial.

Queen Alexandra

Queen consort

With the death of her mother-in-law, Queen Victoria, in 1901, Alexandra became queen-empress consort to the new king. Just two months later, her surviving son George and daughter-in-law MaryMary of Teck

Mary of Teck was the queen consort of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, as the wife of King-Emperor George V....

left on an extensive tour of the empire, leaving their young children in the care of Alexandra and Edward, who doted on their grandchildren. On George's return, preparations for the coronation

Coronation of the British monarch

The coronation of the British monarch is a ceremony in which the monarch of the United Kingdom is formally crowned and invested with regalia...

of Edward and Alexandra were well in hand. Just a few days before the scheduled coronation in June 1902, however, Edward became seriously ill with an appendix abscess or appendicitis

Appendicitis

Appendicitis is a condition characterized by inflammation of the appendix. It is classified as a medical emergency and many cases require removal of the inflamed appendix, either by laparotomy or laparoscopy. Untreated, mortality is high, mainly because of the risk of rupture leading to...

. Alexandra deputised for him at a military parade, and attended the Royal Ascot races

Ascot Racecourse

Ascot Racecourse is a famous English racecourse, located in the small town of Ascot, Berkshire, used for thoroughbred horse racing. It is one of the leading racecourses in the United Kingdom, hosting 9 of the UK's 32 annual Group 1 races...

without him, in an attempt to prevent public alarm. Eventually, the coronation had to be postponed and Edward had an operation performed by Frederick Treves

Sir Frederick Treves, 1st Baronet

Sir Frederick Treves, 1st Baronet, GCVO, CH, CB was a prominent British surgeon of the Victorian and Edwardian eras, now most famous for his friendship with Joseph Merrick, "the Elephant Man".-Eminent surgeon:...

of the London Hospital to drain the infected appendix. After his recovery, Alexandra and Edward were crowned together in August: he by the Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

, Frederick Temple

Frederick Temple

Frederick Temple was an English academic, teacher, churchman and Archbishop of Canterbury from 1896 until his death.-Early life:...

, and she by the Archbishop of York

Archbishop of York

The Archbishop of York is a high-ranking cleric in the Church of England, second only to the Archbishop of Canterbury. He is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and metropolitan of the Province of York, which covers the northern portion of England as well as the Isle of Man...

, William Dalrymple Maclagan

William Dalrymple Maclagan

William Dalrymple Maclagan PC was Archbishop of York from 1891 to 1908, when he resigned his office, and was succeeded in 1909 by Cosmo Gordon Lang, later Archbishop of Canterbury...

.

Despite now being queen, Alexandra's duties changed little, and she kept many of the same retainers. Alexandra's Woman of the Bedchamber

Woman of the Bedchamber

In the Royal Household of the United Kingdom the term Woman of the Bedchamber is used to describe a woman attending either a queen regnant or queen consort, in the role of Lady-in-Waiting...

, Charlotte Knollys

Charlotte Knollys

Elizabeth Charlotte Knollys was a Lady of the Bedchamber, and the first woman private secretary, to Princess Alexandra of Denmark, later Queen Alexandra of the United Kingdom, consort of Edward VII of the United Kingdom.-Biography:...

, served Alexandra loyally for many years. On 10 December 1903, Charlotte, the daughter of Sir William Knollys, woke to find her bedroom full of smoke. She roused Alexandra and shepherded her to safety. In the words of Grand Duchess Augusta of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, "We must give credit to old Charlotte for really saving [Alexandra's] life."

Alexandra again looked after her grandchildren when George and Mary went on a second tour, this time to British India, over the winter of 1905–06. Her father, King Christian IX of Denmark, died that January. Eager to retain their family links, to both each other and to Denmark, in 1907 Alexandra and her sister, the Dowager Empress of Russia, purchased a villa north of Copenhagen, Hvidøre, as a private getaway.

Biographers have asserted that Alexandra was denied access to the King's briefing papers and excluded from some of the King's foreign tours to prevent her meddling in diplomatic matters. She was deeply distrustful of Germans, and invariably opposed anything that favoured German expansion or interests. For example, in 1890 Alexandra wrote a memorandum, distributed to senior British ministers and military personnel, warning against the planned exchange of the British North Sea

North Sea

In the southwest, beyond the Straits of Dover, the North Sea becomes the English Channel connecting to the Atlantic Ocean. In the east, it connects to the Baltic Sea via the Skagerrak and Kattegat, narrow straits that separate Denmark from Norway and Sweden respectively...

island of Heligoland

Heligoland

Heligoland is a small German archipelago in the North Sea.Formerly Danish and British possessions, the islands are located in the Heligoland Bight in the south-eastern corner of the North Sea...

for the German colony of Zanzibar

Zanzibar

Zanzibar ,Persian: زنگبار, from suffix bār: "coast" and Zangi: "bruin" ; is a semi-autonomous part of Tanzania, in East Africa. It comprises the Zanzibar Archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of numerous small islands and two large ones: Unguja , and Pemba...

, pointing out Heligoland's strategic significance and that it could be used either by Germany to launch an attack, or by Britain to contain German aggression. Despite this, the exchange went ahead anyway. The Germans fortified the island and, in the words of Robert Ensor

Robert Ensor

Sir Robert Charles Kirkwood Ensor was a British writer, poet, journalist, liberal intellectual and historian. He is famous for his extremely popular volume of the Oxford History of England, covering the years 1870 to 1914. Originally the final volume, Ensor's book has sold more copies than any...

and as Alexandra had predicted, it "became the keystone of Germany's maritime position for offence as well as for defence". The Frankfurter Zeitung

Frankfurter Zeitung

The Frankfurter Zeitung was a German language newspaper that appeared from 1856 to 1943. It emerged from a market letter that was published in Frankfurt...

was outspoken in its condemnation of Alexandra and her sister, the Dowager Empress of Russia, saying that the pair were "the centre of the international anti-German conspiracy". She despised and distrusted her nephew, Wilhelm II of Germany, calling him in 1900 "inwardly our enemy".

In 1910, Alexandra became the first queen consort to visit the British House of Commons

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

during a debate. In a remarkable departure from precedent, for two hours she sat in the Ladies' Gallery overlooking the chamber while the Parliament Bill

Parliament Act 1911

The Parliament Act 1911 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords which make up the Houses of Parliament. This Act must be construed as one with the Parliament Act 1949...

, a bill to reform the role of the House of Lords

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

, was debated. Privately, Alexandra disagreed with the bill. Shortly afterward, she left to visit her brother, King George I of Greece, in Corfu

Corfu

Corfu is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea. It is the second largest of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the edge of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The island is part of the Corfu regional unit, and is administered as a single municipality. The...

. While there, she received news that King Edward was seriously ill. Alexandra returned at once and arrived just the day before her husband died. In his last hours, she personally administered oxygen from a gas cylinder to help him breathe. She told Frederick Ponsonby

Frederick Ponsonby, 1st Baron Sysonby

Frederick Edward Grey Ponsonby, 1st Baron Sysonby GCB GCVO PC , was a British soldier and courtier.Ponsonby was the second son of General Sir Henry Ponsonby and his wife the Hon. Mary Elizabeth...

, "I feel as if I had been turned into stone, unable to cry, unable to grasp the meaning of it all." Later that year, she moved out of Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace, in London, is the principal residence and office of the British monarch. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is a setting for state occasions and royal hospitality...

to Marlborough House

Marlborough House

Marlborough House is a mansion in Westminster, London, in Pall Mall just east of St James's Palace. It was built for Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough, the favourite and confidante of Queen Anne. The Duchess wanted her new house to be "strong, plain and convenient and good"...

, but she retained possession of Sandringham. The new king, Alexandra's son George

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

, soon faced a decision over the Parliament Bill. Despite her personal views, Alexandra supported the King's decision to help force the bill through Parliament at the Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

's request but against the wishes of the House of Lords when the reforming party won elections to the House of Commons.

Queen mother

Alexandra Rose Day

Alexandra Rose Day is a charitable fund raising event held in the United Kingdom since 1912. It was first launched on the 50th anniversary of the arrival of Queen Alexandra, the consort of King Edward VII, from her native Denmark to the UK...

, where artificial roses made by the disabled were sold in aid of hospitals by women volunteers. During the First World War

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, the custom of hanging the banners of foreign princes invested with Britain's highest order of knighthood, the Order of the Garter

Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter, founded in 1348, is the highest order of chivalry, or knighthood, existing in England. The order is dedicated to the image and arms of St...

, in St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle

St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle

St George's Chapel is the place of worship at Windsor Castle in England, United Kingdom. It is both a royal peculiar and the chapel of the Order of the Garter...

, came under criticism, as the German members of the Order were fighting against Britain. Alexandra joined calls to "have down those hateful German banners". Driven by public opinion, but against his own wishes, the King had the banners removed but to Alexandra's dismay he had down not only "those vile Prussian banners" but also those of her Hessian relations who were, in her opinion, "simply soldiers or vassals under that brutal German Emperor's orders". On 17 September 1916, she was at Sandringham during a Zeppelin

Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship pioneered by the German Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin in the early 20th century. It was based on designs he had outlined in 1874 and detailed in 1893. His plans were reviewed by committee in 1894 and patented in the United States on 14 March 1899...

air raid, but far worse was to befall other members of her family. In Russia, her nephew Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II of Russia

Nicholas II was the last Emperor of Russia, Grand Prince of Finland, and titular King of Poland. His official short title was Nicholas II, Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias and he is known as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer by the Russian Orthodox Church.Nicholas II ruled from 1894 until...

was overthrown and he, his wife and children were killed by revolutionaries. Her sister the Dowager Empress was rescued from Russia in 1919 by and brought to England where she lived for some time with Alexandra.