Ancien Régime in France

Encyclopedia

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

, social

Sociology

Sociology is the study of society. It is a social science—a term with which it is sometimes synonymous—which uses various methods of empirical investigation and critical analysis to develop a body of knowledge about human social activity...

and political

Politics

Politics is a process by which groups of people make collective decisions. The term is generally applied to the art or science of running governmental or state affairs, including behavior within civil governments, but also applies to institutions, fields, and special interest groups such as the...

system established in France from (roughly) the 15th century to the 18th century under the late Valois

Valois Dynasty

The House of Valois was a cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty, succeeding the House of Capet as kings of France from 1328 to 1589...

and Bourbon

House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon is a European royal house, a branch of the Capetian dynasty . Bourbon kings first ruled Navarre and France in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Bourbon dynasty also held thrones in Spain, Naples, Sicily, and Parma...

dynasties. The administrative and social structures of the Ancien Régime were the result of years of state-building, legislative acts (like the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts

Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts

The Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts is an extensive piece of reform legislation signed into law by Francis I of France on August 10, 1539 in the city of Villers-Cotterêts....

), internal conflicts and civil wars, but they remained a confusing patchwork of local privilege

Privilege

A privilege is a special entitlement to immunity granted by the state or another authority to a restricted group, either by birth or on a conditional basis. It can be revoked in certain circumstances. In modern democratic states, a privilege is conditional and granted only after birth...

and historic differences until the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

ended the system.

Much of the medieval political centralization of France had been lost in the Hundred Years' War

Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War was a series of separate wars waged from 1337 to 1453 by the House of Valois and the House of Plantagenet, also known as the House of Anjou, for the French throne, which had become vacant upon the extinction of the senior Capetian line of French kings...

, and the Valois Dynasty's attempts at re-establishing control over the scattered political centres of the country were hindered by the Wars of Religion

French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the name given to a period of civil infighting and military operations, primarily fought between French Catholics and Protestants . The conflict involved the factional disputes between the aristocratic houses of France, such as the House of Bourbon and House of Guise...

. Much of the reigns of Henry IV

Henry IV of France

Henry IV , Henri-Quatre, was King of France from 1589 to 1610 and King of Navarre from 1572 to 1610. He was the first monarch of the Bourbon branch of the Capetian dynasty in France....

, Louis XIII

Louis XIII of France

Louis XIII was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and of Navarre from 1610 to 1643.Louis was only eight years old when he succeeded his father. His mother, Marie de Medici, acted as regent during Louis' minority...

and the early years of Louis XIV

Louis XIV of France

Louis XIV , known as Louis the Great or the Sun King , was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and Navarre. His reign, from 1643 to his death in 1715, began at the age of four and lasted seventy-two years, three months, and eighteen days...

were focused on administrative centralization. Despite, however, the notion of "absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy is a monarchical form of government in which the monarch exercises ultimate governing authority as head of state and head of government, his or her power not being limited by a constitution or by the law. An absolute monarch thus wields unrestricted political power over the...

" (typified by the king's right to issue lettres de cachet

Lettre de cachet

Lettres de cachet were letters signed by the king of France, countersigned by one of his ministers, and closed with the royal seal, or cachet...

) and the efforts by the kings to create a centralized state, ancien régime France remained a country of systemic irregularities: administrative (including taxation), legal, judicial, and ecclesiastic divisions and prerogatives frequently overlapped, while the French nobility

French nobility

The French nobility was the privileged order of France in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern periods.In the political system of the Estates General, the nobility made up the Second Estate...

struggled to maintain their own rights in the matters of local government and justice, and powerful internal conflicts (like the Fronde

Fronde

The Fronde was a civil war in France, occurring in the midst of the Franco-Spanish War, which had begun in 1635. The word fronde means sling, which Parisian mobs used to smash the windows of supporters of Cardinal Mazarin....

) protested against this centralization.

The need for centralization in this period was directly linked to the question of royal finances and the ability to wage war. The internal conflicts and dynastic crises of the 16th and 17th centuries (the Wars of Religion

French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the name given to a period of civil infighting and military operations, primarily fought between French Catholics and Protestants . The conflict involved the factional disputes between the aristocratic houses of France, such as the House of Bourbon and House of Guise...

, the conflict with the Habsburgs) and the territorial expansion of France in the 17th century demanded great sums which needed to be raised through taxes, such as the taille

Taille

The taille was a direct land tax on the French peasantry and non-nobles in Ancien Régime France. The tax was imposed on each household and based on how much land it held.-History:Originally only an "exceptional" tax The taille was a direct land tax on the French peasantry and non-nobles in Ancien...

and the gabelle

Gabelle

The gabelle was a very unpopular tax on salt in France before 1790. The term gabelle derives from the Italian gabella , itself from the Arabic qabala....

and by contributions of men and service from the nobility.

One key to this centralization was the replacing of personal "clientele

Patrón

Patrón is a luxury brand of tequila produced in Mexico and sold in hand-blown, individually numbered bottles.Made entirely from Blue Agave "piñas" , Patrón comes in five varieties: Silver, Añejo, Reposado, Gran Patrón Platinum and Gran Patrón Burdeos. Patrón also sells a tequila-coffee blend known...

" systems organized around the king and other nobles

French nobility

The French nobility was the privileged order of France in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern periods.In the political system of the Estates General, the nobility made up the Second Estate...

by institutional systems around the state. The creation of the Intendant

Intendant

The title of intendant has been used in several countries through history. Traditionally, it refers to the holder of a public administrative office...

s—representatives of royal power in the provinces—did much to undermine local control by regional nobles. The same was true of the greater reliance shown by the royal court on the "noblesse de robe

French nobility

The French nobility was the privileged order of France in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern periods.In the political system of the Estates General, the nobility made up the Second Estate...

" as judges and royal counselors. The creation of regional parlement

Parlement

Parlements were regional legislative bodies in Ancien Régime France.The political institutions of the Parlement in Ancien Régime France developed out of the previous council of the king, the Conseil du roi or curia regis, and consequently had ancient and customary rights of consultation and...

s had initially the same goal of facilitating the introduction of royal power into newly assimilated territories, but as the parlements gained in self-assurance, they began to be sources of disunity.

Terminology

The term is French for "Former Regime", but rendered in English as "Old (or Ancient) Regime", "Old Order", or "Old Rule".The term dates from the Age of Enlightenment

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

(first appearing in print in English in 1794) and was originally pejorative in nature. Similar to other sweeping criticisms of the past, such as the consciously disparaging term Dark Ages for what is more commonly known as the Early Middle Ages

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages was the period of European history lasting from the 5th century to approximately 1000. The Early Middle Ages followed the decline of the Western Roman Empire and preceded the High Middle Ages...

, ancien regime was not a neutral historical descriptor. It was created by the French Revolutionaries to promote their cause, coloring pre-revolutionary society with disapproval and implying approval of a "New Order".

The analogous term "Antiguo Régimen" is often used in Spanish

Spanish language

Spanish , also known as Castilian , is a Romance language in the Ibero-Romance group that evolved from several languages and dialects in central-northern Iberia around the 9th century and gradually spread with the expansion of the Kingdom of Castile into central and southern Iberia during the...

. However, although Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

was strongly affected by the French Revolution and its aftermath, the break was not as sharp as in France.

More generally, ancien régime refers to any political and social system having the principal features of the French Ancien Regime. Europe's other anciens régimes had similar origins, but diverse fates: some eventually evolved into constitutional monarchies

Constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy is a form of government in which a monarch acts as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, whether it be a written, uncodified or blended constitution...

, whereas others were torn down by wars and revolutions.

Territorial expansion

Roussillon

Roussillon is one of the historical counties of the former Principality of Catalonia, corresponding roughly to the present-day southern French département of Pyrénées-Orientales...

, Cerdagne, Conflent

Conflent

Conflent is a historical Catalan comarca of Northern Catalonia, now part of the French Département of Pyrénées-Orientales. In the Middle Ages it comprised the County of Conflent....

, Vallespir

Vallespir

Vallespir is a historical Catalan comarca of Northern Catalonia, part of the French Département of Pyrénées-Orientales. The capital of the comarca is Ceret, and it borders Conflent, Rosselló, Alt Empordà, Garrotxa and Ripollès...

, Capcir

Capcir

Capcir is a historical Catalan comarca of Northern Catalonia, now part of the French Département of Pyrénées-Orientales. The capital of the comarca was Formiguera, and it borders the historical comarques of Conflent and Alta Cerdanya...

, Calais

Calais

Calais is a town in Northern France in the department of Pas-de-Calais, of which it is a sub-prefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's capital is its third-largest city of Arras....

, Béarn

Béarn

Béarn is one of the traditional provinces of France, located in the Pyrenees mountains and in the plain at their feet, in southwest France. Along with the three Basque provinces of Soule, Lower Navarre, and Labourd, the principality of Bidache, as well as small parts of Gascony, it forms in the...

, Navarre, County of Foix

County of Foix

The County of Foix was an independent medieval fief in southern France, and later a province of France, whose territory corresponded roughly the eastern part of the modern département of Ariège ....

, Flanders, Artois

Artois

Artois is a former province of northern France. Its territory has an area of around 4000 km² and a population of about one million. Its principal cities are Arras , Saint-Omer, Lens and Béthune.-Location:...

, Lorraine

Lorraine (province)

The Duchy of Upper Lorraine was an historical duchy roughly corresponding with the present-day northeastern Lorraine region of France, including parts of modern Luxembourg and Germany. The main cities were Metz, Verdun, and the historic capital Nancy....

, Alsace

Alsace

Alsace is the fifth-smallest of the 27 regions of France in land area , and the smallest in metropolitan France. It is also the seventh-most densely populated region in France and third most densely populated region in metropolitan France, with ca. 220 inhabitants per km²...

, Trois-Évêchés

Three Bishoprics

The Three Bishoprics constituted a province of pre-Revolutionary France consisting of the prince-bishoprics of Verdun, Metz, and Toul within the Lorraine region....

, Franche-Comté

Franche-Comté

Franche-Comté the former "Free County" of Burgundy, as distinct from the neighbouring Duchy, is an administrative region and a traditional province of eastern France...

, Savoy

Savoy

Savoy is a region of France. It comprises roughly the territory of the Western Alps situated between Lake Geneva in the north and Monaco and the Mediterranean coast in the south....

, Bresse

Bresse

Bresse is a former French province. It is located in the regions of Rhône-Alpes, Bourgogne, and Franche-Comté of eastern France. The geographical term Bresse has two meanings: Bresse bourguignonne , which is situated in the east of the department of Saône-et-Loire, and Bresse, which is located...

, Bugey

Bugey

The Bugey is a historical region in the département of Ain , France. It is located in a loop of the Rhône River in the southeast of the département...

, Gex

Gex, Ain

Gex is a commune in the Ain department in eastern France.It lies from the Swiss border and from Geneva. It is a sous-préfecture of Ain.-History:...

, Nice

Nice

Nice is the fifth most populous city in France, after Paris, Marseille, Lyon and Toulouse, with a population of 348,721 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Nice extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of more than 955,000 on an area of...

, Provence

Provence

Provence ; Provençal: Provença in classical norm or Prouvènço in Mistralian norm) is a region of south eastern France on the Mediterranean adjacent to Italy. It is part of the administrative région of Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur...

, Dauphiné

Dauphiné

The Dauphiné or Dauphiné Viennois is a former province in southeastern France, whose area roughly corresponded to that of the present departments of :Isère, :Drôme, and :Hautes-Alpes....

, and Brittany

Brittany

Brittany is a cultural and administrative region in the north-west of France. Previously a kingdom and then a duchy, Brittany was united to the Kingdom of France in 1532 as a province. Brittany has also been referred to as Less, Lesser or Little Britain...

) were either autonomous or belonged to the Holy Roman Empire

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

, the Crown of Aragon

Crown of Aragon

The Crown of Aragon Corona d'Aragón Corona d'Aragó Corona Aragonum controlling a large portion of the present-day eastern Spain and southeastern France, as well as some of the major islands and mainland possessions stretching across the Mediterranean as far as Greece...

or the Kingdom of Navarra; there were also foreign enclaves, like the Comtat Venaissin

Comtat Venaissin

The Comtat Venaissin, often called the Comtat for short , is the former name of the region around the city of Avignon in what is now the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of France. It comprised roughly the area between the Rhône, the Durance and Mont Ventoux, with a small exclave located to the...

. In addition, certain provinces within France were ostensibly personal fiefdoms of noble families (like the Bourbonnais

Bourbonnais

Bourbonnais was a historic province in the centre of France that corresponded to the modern département of Allier, along with part of the département of Cher. Its capital was Moulins.-History:...

, Marche, Forez

Forez

Forez is a former province of France, corresponding approximately to the central part of the modern Loire département and a part of the Haute-Loire and Puy-de-Dôme départements....

and Auvergne

Auvergne (province)

Auvergne was a historic province in south central France. It was originally the feudal domain of the Counts of Auvergne. It is now the geographical and cultural area that corresponds to the former province....

provinces held by the House of Bourbon

House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon is a European royal house, a branch of the Capetian dynasty . Bourbon kings first ruled Navarre and France in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Bourbon dynasty also held thrones in Spain, Naples, Sicily, and Parma...

until the provinces were forcibly integrated into the royal domain

Crown lands of France

The crown lands, crown estate, royal domain or domaine royal of France refers to the lands, fiefs and rights directly possessed by the kings of France...

in 1527 after the fall of Charles III, Duke of Bourbon

Charles III, Duke of Bourbon

Charles III, Duke of Bourbon was a French military leader, the Count of Montpensier and Dauphin of Auvergne. He commanded the Imperial troops of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in what became known as the Sack of Rome in 1527, where he was killed.-Biography:Charles was born at Montpensier...

).

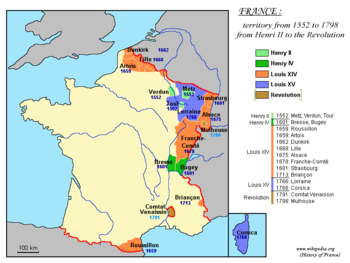

From the late fifteenth century up to the late seventenenth century, (and again in the 1760s) France underwent a massive territorial expansion and an attempt to better integrate its provinces into an administrative whole.

French acquisitions from 1461-1768:

- under Louis XILouis XI of FranceLouis XI , called the Prudent , was the King of France from 1461 to 1483. He was the son of Charles VII of France and Mary of Anjou, a member of the House of Valois....

- ProvenceProvenceProvence ; Provençal: Provença in classical norm or Prouvènço in Mistralian norm) is a region of south eastern France on the Mediterranean adjacent to Italy. It is part of the administrative région of Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur...

(1482), DauphinéDauphinéThe Dauphiné or Dauphiné Viennois is a former province in southeastern France, whose area roughly corresponded to that of the present departments of :Isère, :Drôme, and :Hautes-Alpes....

(1461, under French control since 1349) - under Francis IFrancis I of FranceFrancis I was King of France from 1515 until his death. During his reign, huge cultural changes took place in France and he has been called France's original Renaissance monarch...

- BrittanyBrittanyBrittany is a cultural and administrative region in the north-west of France. Previously a kingdom and then a duchy, Brittany was united to the Kingdom of France in 1532 as a province. Brittany has also been referred to as Less, Lesser or Little Britain...

(1532) - under Henry IIHenry II of FranceHenry II was King of France from 31 March 1547 until his death in 1559.-Early years:Henry was born in the royal Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, near Paris, the son of Francis I and Claude, Duchess of Brittany .His father was captured at the Battle of Pavia in 1525 by his sworn enemy,...

- CalaisCalaisCalais is a town in Northern France in the department of Pas-de-Calais, of which it is a sub-prefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's capital is its third-largest city of Arras....

, Trois-ÉvêchésThree BishopricsThe Three Bishoprics constituted a province of pre-Revolutionary France consisting of the prince-bishoprics of Verdun, Metz, and Toul within the Lorraine region....

(1552) - under Henry IVHenry IV of FranceHenry IV , Henri-Quatre, was King of France from 1589 to 1610 and King of Navarre from 1572 to 1610. He was the first monarch of the Bourbon branch of the Capetian dynasty in France....

- County of FoixCounty of FoixThe County of Foix was an independent medieval fief in southern France, and later a province of France, whose territory corresponded roughly the eastern part of the modern département of Ariège ....

(1607) - under Louis XIIILouis XIII of FranceLouis XIII was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and of Navarre from 1610 to 1643.Louis was only eight years old when he succeeded his father. His mother, Marie de Medici, acted as regent during Louis' minority...

- BéarnBéarnBéarn is one of the traditional provinces of France, located in the Pyrenees mountains and in the plain at their feet, in southwest France. Along with the three Basque provinces of Soule, Lower Navarre, and Labourd, the principality of Bidache, as well as small parts of Gascony, it forms in the...

and Navarre (1620, under French control since 1589 as part of Henry IVHenry IV of FranceHenry IV , Henri-Quatre, was King of France from 1589 to 1610 and King of Navarre from 1572 to 1610. He was the first monarch of the Bourbon branch of the Capetian dynasty in France....

's possessions) - under Louis XIVLouis XIV of FranceLouis XIV , known as Louis the Great or the Sun King , was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and Navarre. His reign, from 1643 to his death in 1715, began at the age of four and lasted seventy-two years, three months, and eighteen days...

- Treaty of Westphalia (1648) - AlsaceAlsaceAlsace is the fifth-smallest of the 27 regions of France in land area , and the smallest in metropolitan France. It is also the seventh-most densely populated region in France and third most densely populated region in metropolitan France, with ca. 220 inhabitants per km²...

- Treaty of the PyreneesTreaty of the PyreneesThe Treaty of the Pyrenees was signed to end the 1635 to 1659 war between France and Spain, a war that was initially a part of the wider Thirty Years' War. It was signed on Pheasant Island, a river island on the border between the two countries...

(1659) - ArtoisArtoisArtois is a former province of northern France. Its territory has an area of around 4000 km² and a population of about one million. Its principal cities are Arras , Saint-Omer, Lens and Béthune.-Location:...

, Northern CataloniaNorthern CataloniaNorthern Catalonia is a term that is sometimes used, particularly in Catalan writings, to refer to the territory ceded to France by Spain through the signing of the Treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659...

(RoussillonRoussillonRoussillon is one of the historical counties of the former Principality of Catalonia, corresponding roughly to the present-day southern French département of Pyrénées-Orientales...

, Cerdagne) - Treaty of Nijmegen (1678-9) - Franche-ComtéFranche-ComtéFranche-Comté the former "Free County" of Burgundy, as distinct from the neighbouring Duchy, is an administrative region and a traditional province of eastern France...

, Flanders

- Treaty of Westphalia (1648) - Alsace

- under Louis XVLouis XV of FranceLouis XV was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and of Navarre from 1 September 1715 until his death. He succeeded his great-grandfather at the age of five, his first cousin Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, served as Regent of the kingdom until Louis's majority in 1723...

- LorraineLorraine (province)The Duchy of Upper Lorraine was an historical duchy roughly corresponding with the present-day northeastern Lorraine region of France, including parts of modern Luxembourg and Germany. The main cities were Metz, Verdun, and the historic capital Nancy....

(1766), CorsicaCorsicaCorsica is an island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is located west of Italy, southeast of the French mainland, and north of the island of Sardinia....

(1768)

Administration

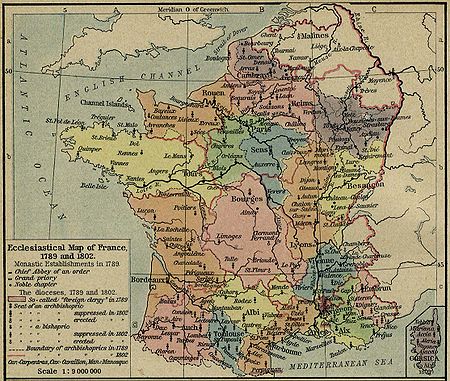

Despite efforts by the kings to create a centralized state out of these provinces, France in this period remained a patchwork of local privileges and historical differences, and the arbitrary power of the monarch (as implied by the expression "absolute monarchy") was in fact much limited by historic and regional particularities. Administrative (including taxation), legal (parlementParlement

Parlements were regional legislative bodies in Ancien Régime France.The political institutions of the Parlement in Ancien Régime France developed out of the previous council of the king, the Conseil du roi or curia regis, and consequently had ancient and customary rights of consultation and...

), judicial, and ecclesiastic divisions and prerogatives frequently overlapped (for example, French bishoprics and dioceses rarely coincided with administrative divisions). Certain provinces and cities had won special privileges (such as lower rates in the gabelle

Gabelle

The gabelle was a very unpopular tax on salt in France before 1790. The term gabelle derives from the Italian gabella , itself from the Arabic qabala....

or salt tax). The south of France was governed by written law adapted from the Roman legal system

Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, and the legal developments which occurred before the 7th century AD — when the Roman–Byzantine state adopted Greek as the language of government. The development of Roman law comprises more than a thousand years of jurisprudence — from the Twelve...

, the north of France by common law

Common law

Common law is law developed by judges through decisions of courts and similar tribunals rather than through legislative statutes or executive branch action...

(in 1453 these common laws were codified into a written form).

The representative of the king in his provinces and cities was the "gouverneur". Royal officers chosen from the highest nobility, provincial and city governors (oversight of provinces and cities was frequently combined) were predominantly military positions in charge of defense and policing. Provincial governors — also called "lieutenants généraux" — also had the ability of convoking provincial parlements, provincial estates and municipal bodies. The title "gouverneur" first appeared under Charles VI

Charles VI of France

Charles VI , called the Beloved and the Mad , was the King of France from 1380 to 1422, as a member of the House of Valois. His bouts with madness, which seem to have begun in 1392, led to quarrels among the French royal family, which were exploited by the neighbouring powers of England and Burgundy...

. The ordinance of Blois of 1579 reduced their number to 12, but an ordinance of 1779 increased their number to 39 (18 first-class governors, 21 second-class governors). Although in principle they were the king's representatives and their charges could be revoked at the king's will, some governors had installed themselves and their heirs as a provincial dynasty. The governors were at the height of their power from the middle of the 16th to the mid-17th century, but their role in provincial unrest during the civil wars led Cardinal Richelieu to create the more tractable positions of intendant

Intendant

The title of intendant has been used in several countries through history. Traditionally, it refers to the holder of a public administrative office...

s of finance, policing and justice, and in the 18th century the role of provincial governors was greatly curtailed.

| Major Provinces of France, with provincial capitals. Cities in bold had provincial "parlement Parlement Parlements were regional legislative bodies in Ancien Régime France.The political institutions of the Parlement in Ancien Régime France developed out of the previous council of the king, the Conseil du roi or curia regis, and consequently had ancient and customary rights of consultation and... s" or "conseils souverains" during the ancien régime. Note: The map reflects France's modern borders and does not indicate the territorial formation of France over time. Provinces on this list may encompass several other historic provinces and counties (for example, at the time of the Revolution, Guyenne Guyenne Guyenne or Guienne , , ; Occitan Guiana ) is a vaguely defined historic region of south-western France. The Province of Guyenne, sometimes called the Province of Guyenne and Gascony, was a large province of pre-revolutionary France.... was made up of eight smaller historic provinces, including Quercy Quercy Quercy is a former province of France located in the country's southwest, bounded on the north by Limousin, on the west by Périgord and Agenais, on the south by Gascony and Languedoc, and on the east by Rouergue and Auvergne.... and Rouergue Rouergue Rouergue is a former province of France, bounded on the north by Auvergne, on the south and southwest by Languedoc, on the east by Gévaudan and on the west by Quercy... ). For a more complete list, see Provinces of France Provinces of France The Kingdom of France was organised into provinces until March 4, 1790, when the establishment of the département system superseded provinces. The provinces of France were roughly equivalent to the historic counties of England... . |

||

|---|---|---|

|

County of Foix The County of Foix was an independent medieval fief in southern France, and later a province of France, whose territory corresponded roughly the eastern part of the modern département of Ariège .... (Foix Foix Foix is a commune, the capital of the Ariège department in southwestern France. It is the least populous administrative centre of a department in all of France, although it is only very slightly smaller than Privas... ) Auvergne (province) Auvergne was a historic province in south central France. It was originally the feudal domain of the Counts of Auvergne. It is now the geographical and cultural area that corresponds to the former province.... (Clermont-Ferrand Clermont-Ferrand Clermont-Ferrand is a city and commune of France, in the Auvergne region, with a population of 140,700 . Its metropolitan area had 409,558 inhabitants at the 1999 census. It is the prefecture of the Puy-de-Dôme department... ) Béarn Béarn is one of the traditional provinces of France, located in the Pyrenees mountains and in the plain at their feet, in southwest France. Along with the three Basque provinces of Soule, Lower Navarre, and Labourd, the principality of Bidache, as well as small parts of Gascony, it forms in the... (Pau) Alsace Alsace is the fifth-smallest of the 27 regions of France in land area , and the smallest in metropolitan France. It is also the seventh-most densely populated region in France and third most densely populated region in metropolitan France, with ca. 220 inhabitants per km²... (Strasbourg Strasbourg Strasbourg is the capital and principal city of the Alsace region in eastern France and is the official seat of the European Parliament. Located close to the border with Germany, it is the capital of the Bas-Rhin département. The city and the region of Alsace are historically German-speaking,... , cons. souv. in Colmar Colmar Colmar is a commune in the Haut-Rhin department in Alsace in north-eastern France.It is the capital of the department. Colmar is also the seat of the highest jurisdiction in Alsace, the appellate court.... ) Artois Artois is a former province of northern France. Its territory has an area of around 4000 km² and a population of about one million. Its principal cities are Arras , Saint-Omer, Lens and Béthune.-Location:... (cons provinc. in Arras Arras Arras is the capital of the Pas-de-Calais department in northern France. The historic centre of the Artois region, its local speech is characterized as a Picard dialect... ) Roussillon Roussillon is one of the historical counties of the former Principality of Catalonia, corresponding roughly to the present-day southern French département of Pyrénées-Orientales... (cons. souv. in Perpignan Perpignan -Sport:Perpignan is a rugby stronghold: their rugby union side, USA Perpignan, is a regular competitor in the Heineken Cup and seven times champion of the Top 14 , while their rugby league side plays in the engage Super League under the name Catalans Dragons.-Culture:Since 2004, every year in the... ) County of Hainaut The County of Hainaut was a historical region in the Low Countries with its capital at Mons . In English sources it is often given the archaic spelling Hainault.... (Lille Lille Lille is a city in northern France . It is the principal city of the Lille Métropole, the fourth-largest metropolitan area in the country behind those of Paris, Lyon and Marseille. Lille is situated on the Deûle River, near France's border with Belgium... , parliament first in Tournai Tournai Tournai is a Walloon city and municipality of Belgium located 85 kilometres southwest of Brussels, on the river Scheldt, in the province of Hainaut.... , then in Douai Douai -Main sights:Douai's ornate Gothic style belfry was begun in 1380, on the site of an earlier tower. The 80 m high structure includes an impressive carillon, consisting of 62 bells spanning 5 octaves. The originals, some dating from 1391 were removed in 1917 during World War I by the occupying... ) Franche-Comté Franche-Comté the former "Free County" of Burgundy, as distinct from the neighbouring Duchy, is an administrative region and a traditional province of eastern France... (Besançon Parlement of Besançon The Parlement of Besançon was the Ancien Regime Parlement that dealt with the Franche-Comté. It was created in 1676. The previous Parlement for much of the reason had been at Dôle, and had been created in 1422.... , formerly at Dôle Dole Dole may refer to:*The Grain supply to the city of Rome in ancient times.* Since the early 20th Century, a colloquial term referring to government public assistance programs; see Unemployment benefits. Originally it referred to any charitable gift of food, clothing or money. The dole has taken on... ) Lorraine (province) The Duchy of Upper Lorraine was an historical duchy roughly corresponding with the present-day northeastern Lorraine region of France, including parts of modern Luxembourg and Germany. The main cities were Metz, Verdun, and the historic capital Nancy.... (Nancy) Corsica Corsica is an island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is located west of Italy, southeast of the French mainland, and north of the island of Sardinia.... (off map, Ajaccio Ajaccio Ajaccio , is a commune on the island of Corsica in France. It is the capital and largest city of the region of Corsica and the prefecture of the department of Corse-du-Sud.... , cons. souv. in Bastia Bastia Bastia is a commune in the Haute-Corse department of France located in the northeast of the island of Corsica at the base of Cap Corse. It is also the second-largest city in Corsica after Ajaccio and the capital of the department.... ) Nivernais Nivernais is former province of France, around the city of Nevers and the département of Nièvre.The raw climate and soils cause the area to be heavily wooded.- References :* Chamber's Encyclopedia Volume 10 page 50... (Nevers Nevers Nevers is a commune in – and the administrative capital of – the Nièvre department in the Bourgogne region in central France... ) Comtat Venaissin The Comtat Venaissin, often called the Comtat for short , is the former name of the region around the city of Avignon in what is now the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of France. It comprised roughly the area between the Rhône, the Durance and Mont Ventoux, with a small exclave located to the... (Avignon Avignon Avignon is a French commune in southeastern France in the départment of the Vaucluse bordered by the left bank of the Rhône river. Of the 94,787 inhabitants of the city on 1 January 2010, 12 000 live in the ancient town centre surrounded by its medieval ramparts.Often referred to as the... ), a Papal Papal States The Papal State, State of the Church, or Pontifical States were among the major historical states of Italy from roughly the 6th century until the Italian peninsula was unified in 1861 by the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia .The Papal States comprised territories under... fief Mulhouse Mulhouse |mill]] hamlet) is a city and commune in eastern France, close to the Swiss and German borders. With a population of 110,514 and 278,206 inhabitants in the metropolitan area in 2006, it is the largest city in the Haut-Rhin département, and the second largest in the Alsace region after... Savoy Savoy is a region of France. It comprises roughly the territory of the Western Alps situated between Lake Geneva in the north and Monaco and the Mediterranean coast in the south.... , a Sardinian Kingdom of Sardinia The Kingdom of Sardinia consisted of the island of Sardinia first as a part of the Crown of Aragon and subsequently the Spanish Empire , and second as a part of the composite state of the House of Savoy . Its capital was originally Cagliari, in the south of the island, and later Turin, on the... fief (parl. in Chambéry Chambéry Chambéry is a city in the department of Savoie, located in the Rhône-Alpes region in southeastern France.It is the capital of the department and has been the historical capital of the Savoy region since the 13th century, when Amadeus V of Savoy made the city his seat of power.-Geography:Chambéry... 1537-1559) Nice Nice is the fifth most populous city in France, after Paris, Marseille, Lyon and Toulouse, with a population of 348,721 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Nice extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of more than 955,000 on an area of... , a Sardinian Kingdom of Sardinia The Kingdom of Sardinia consisted of the island of Sardinia first as a part of the Crown of Aragon and subsequently the Spanish Empire , and second as a part of the composite state of the House of Savoy . Its capital was originally Cagliari, in the south of the island, and later Turin, on the... fief Montbéliard Montbéliard is a city in the Doubs department in the Franche-Comté region in eastern France. It is one of the two subprefectures of the department.-History:... , a fief of Württemberg Württemberg Württemberg , formerly known as Wirtemberg or Wurtemberg, is an area and a former state in southwestern Germany, including parts of the regions Swabia and Franconia.... Three Bishoprics The Three Bishoprics constituted a province of pre-Revolutionary France consisting of the prince-bishoprics of Verdun, Metz, and Toul within the Lorraine region.... (Metz Diocese of Metz The Roman Catholic Diocese of Metz is a Diocese of the Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic church in France. In the Middle Ages it was in effect an independent state, part of the Holy Roman Empire, ruled by the bishop who had the ex officio title of count. It was annexed to France by King Henry II in... , Toul Diocese of Toul The Diocese of Toul was a Roman Catholic diocese seated at Toul in present-day France. It existed from 365 until 1824. From 1048 until 1552 , it was also a state of the Holy Roman Empire.- History :... and Verdun) Dombes The Dombes is an area in South-Eastern France, once an independent municipality, formerly part of the province of Burgundy, and now a district comprised in the département of Ain, and bounded W. by the Saône River, by the Rhône, E. by the Ain and N... (Trévoux Trévoux Trévoux is a commune in the Ain department in eastern France.It is a suburb of Lyon.-History:The town was the capital of the Dombes principality, and famed for its dictionary... ) Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port is a commune in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department in south-western France close to Ostabat in the Pyrenean foothills.... ) Soule Soule is a former viscounty and French province and part of the present day Pyrénées-Atlantiques département... (Mauléon Mauléon-Licharre Mauléon-Licharre or simply Mauléon is a commune in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department in south-western France.It is the capital of the Soule historical French and Basque province.It is also home to the canvas shoe, the espadrille.... ) Bigorre Bigorre is region in southwest France, historically an independent county and later a French province, located in the upper watershed of the Adour, on the northern slopes of the Pyrenees, part of the larger region known as Gascony... (Tarbes Tarbes Tarbes is a commune in the Hautes-Pyrénées department in south-western France.It is part of the historical region of Gascony. It is the second largest metropolitan area of Midi-Pyrénées, with 110,000 inhabitants.... ) Beaujolais Beaujolais is a French Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée wine generally made of the Gamay grape which has a thin skin and is low in tannins. Like most AOC wines they are not labeled varietally. Whites from the region, which make up only 1% of its production, are made mostly with Chardonnay grapes... (Beaujeu Beaujeu, Rhône Beaujeu is a commune of the Rhône department in eastern France.It lies between Mâcon and Lyon.Beaujeu gives its name to the famous wine region of Beaujolais , a former province of France of which it is the historical capital... ) Bresse Bresse is a former French province. It is located in the regions of Rhône-Alpes, Bourgogne, and Franche-Comté of eastern France. The geographical term Bresse has two meanings: Bresse bourguignonne , which is situated in the east of the department of Saône-et-Loire, and Bresse, which is located... (Bourg Bourg-en-Bresse Bourg-en-Bresse is a commune in eastern France, capital of the Ain department, and was capital of the former province of Bresse . It is located north-northeast of Lyon.The inhabitants of Bourg-en-Bresse are known as Burgiens.-Geography:... ) Perche Perche is a former province of northern France extending over the départements of Orne, Eure, Eure-et-Loir and Sarthe, which were created from Perche during the French Revolution.-Geography:... (Mortagne-au-Perche Mortagne-au-Perche Mortagne-au-Perche is a commune in the Orne department in north-western France.-Heraldry:-Demographic evolution:* 1962: 3909* 1968: 4322* 1975: 4877* 1982: 4851* 1990: 4584* 1999: 45131962 population without double counting-People:... ) |

|

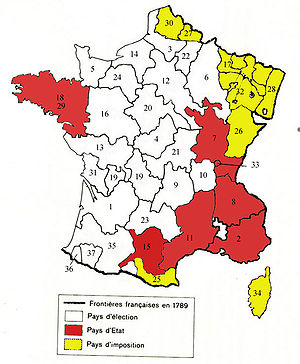

In an attempt to reform the system, new divisions were created. The recettes générales, commonly known as "généralité

Généralité

Recettes générales, commonly known as généralités , were the administrative divisions of France under the Ancien Régime and are often considered to prefigure the current préfectures...

s", were initially only taxation districts (see State finances below). The first sixteen were created in 1542 by edict of Henry II

Henry II of France

Henry II was King of France from 31 March 1547 until his death in 1559.-Early years:Henry was born in the royal Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, near Paris, the son of Francis I and Claude, Duchess of Brittany .His father was captured at the Battle of Pavia in 1525 by his sworn enemy,...

. Their role steadily increased and by the mid 17th century, the généralités were under the authority of a "intendant

Intendant

The title of intendant has been used in several countries through history. Traditionally, it refers to the holder of a public administrative office...

", and they became a vehicle for the expansion of royal power in matters of justice, taxation and policing. By the Revolution, there were 36 généralités; the last two were created in 1784.

| Généralités of France by city (and province). Areas in red are "pays d'état" (note: should also include 36, 37 and parts of 35); white "pays d'élection"; yellow "pays d'imposition" (see State finances below). | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Metz Metz is a city in the northeast of France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers.Metz is the capital of the Lorraine region and prefecture of the Moselle department. Located near the tripoint along the junction of France, Germany, and Luxembourg, Metz forms a central place... (Trois-Évêchés) Nantes Nantes is a city in western France, located on the Loire River, from the Atlantic coast. The city is the 6th largest in France, while its metropolitan area ranks 8th with over 800,000 inhabitants.... (Brittany Brittany Brittany is a cultural and administrative region in the north-west of France. Previously a kingdom and then a duchy, Brittany was united to the Kingdom of France in 1532 as a province. Brittany has also been referred to as Less, Lesser or Little Britain... ) Limoges Limoges |Limousin]] dialect of Occitan) is a city and commune, the capital of the Haute-Vienne department and the administrative capital of the Limousin région in west-central France.... (divided in two parts: Angoumois Angoumois Angoumois was a county and province of France, nearly corresponding today to the Charente département. Its capital was Angoulême.... & Limousin Limousin (province) Limousin is one of the traditional provinces of France around the city of Limoges. Limousin lies in the foothills of the western edge of the Massif Central, with cold weather in the winter... - Marche County of Marche The County of Marche was a medieval French county, approximately corresponding to the modern département of Creuse.Marche first appeared as a separate fief about the middle of the 10th century, when William III, Duke of Aquitaine, gave it to one of his vassals named Boso, who took the title of... ) Orléans -Prehistory and Roman:Cenabum was a Gallic stronghold, one of the principal towns of the Carnutes tribe where the Druids held their annual assembly. It was conquered and destroyed by Julius Caesar in 52 BC, then rebuilt under the Roman Empire... (Orléanais Orléanais Orléanais is a former province of France, around the cities of Orléans, Chartres, and Blois.The name comes from Orléans, its main city and traditional capital. The province was one of those into which France was divided before the French Revolution... ) Moulins, Allier Moulins is a commune in central France, capital of the Allier department.Among its many tourist attractions are the Maison Mantin the Anne de Beaujeu Museum.-History:... (Bourbonnais Bourbonnais Bourbonnais was a historic province in the centre of France that corresponded to the modern département of Allier, along with part of the département of Cher. Its capital was Moulins.-History:... ) Soissons Soissons is a commune in the Aisne department in Picardy in northern France, located on the Aisne River, about northeast of Paris. It is one of the most ancient towns of France, and is probably the ancient capital of the Suessiones... (Picardy Picardy This article is about the historical French province. For other uses, see Picardy .Picardy is a historical province of France, in the north of France... ) Montauban Montauban is a commune in the Tarn-et-Garonne department in the Midi-Pyrénées region in southern France. It is the capital of the department and lies north of Toulouse.... (Gascony Gascony Gascony is an area of southwest France that was part of the "Province of Guyenne and Gascony" prior to the French Revolution. The region is vaguely defined and the distinction between Guyenne and Gascony is unclear; sometimes they are considered to overlap, and sometimes Gascony is considered a... ) Alençon Alençon is a commune in Normandy, France, capital of the Orne department. It is situated west of Paris. Alençon belongs to the intercommunality of Alençon .-History:... (Perche Perche Perche is a former province of northern France extending over the départements of Orne, Eure, Eure-et-Loir and Sarthe, which were created from Perche during the French Revolution.-Geography:... ) Perpignan -Sport:Perpignan is a rugby stronghold: their rugby union side, USA Perpignan, is a regular competitor in the Heineken Cup and seven times champion of the Top 14 , while their rugby league side plays in the engage Super League under the name Catalans Dragons.-Culture:Since 2004, every year in the... (Roussillon Roussillon Roussillon is one of the historical counties of the former Principality of Catalonia, corresponding roughly to the present-day southern French département of Pyrénées-Orientales... ) Besançon Besançon , is the capital and principal city of the Franche-Comté region in eastern France. It had a population of about 237,000 inhabitants in the metropolitan area in 2008... (Franche-Comté Franche-Comté Franche-Comté the former "Free County" of Burgundy, as distinct from the neighbouring Duchy, is an administrative region and a traditional province of eastern France... ) Valenciennes Valenciennes is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.It lies on the Scheldt river. Although the city and region had seen a steady decline between 1975 and 1990, it has since rebounded... (Hainaut County of Hainaut The County of Hainaut was a historical region in the Low Countries with its capital at Mons . In English sources it is often given the archaic spelling Hainault.... ) Strasbourg Strasbourg is the capital and principal city of the Alsace region in eastern France and is the official seat of the European Parliament. Located close to the border with Germany, it is the capital of the Bas-Rhin département. The city and the region of Alsace are historically German-speaking,... (Alsace Alsace Alsace is the fifth-smallest of the 27 regions of France in land area , and the smallest in metropolitan France. It is also the seventh-most densely populated region in France and third most densely populated region in metropolitan France, with ca. 220 inhabitants per km²... ) Lille Lille is a city in northern France . It is the principal city of the Lille Métropole, the fourth-largest metropolitan area in the country behind those of Paris, Lyon and Marseille. Lille is situated on the Deûle River, near France's border with Belgium... (Flanders Flanders Flanders is the community of the Flemings but also one of the institutions in Belgium, and a geographical region located in parts of present-day Belgium, France and the Netherlands. "Flanders" can also refer to the northern part of Belgium that contains Brussels, Bruges, Ghent and Antwerp... ) La Rochelle La Rochelle is a city in western France and a seaport on the Bay of Biscay, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. It is the capital of the Charente-Maritime department.The city is connected to the Île de Ré by a bridge completed on 19 May 1988... (Aunis Aunis Aunis is a historical province of France, situated in the north-west of the department of Charente-Maritime. Its historic capital is La Rochelle, which took over from Castrum Allionis the historic capital which gives its name to the province.... and Saintonge Saintonge Saintonge is a small region on the Atlantic coast of France within the département Charente-Maritime, west and south of Charente in the administrative region of Poitou-Charentes.... ) Lorraine (province) The Duchy of Upper Lorraine was an historical duchy roughly corresponding with the present-day northeastern Lorraine region of France, including parts of modern Luxembourg and Germany. The main cities were Metz, Verdun, and the historic capital Nancy.... ) Trévoux Trévoux is a commune in the Ain department in eastern France.It is a suburb of Lyon.-History:The town was the capital of the Dombes principality, and famed for its dictionary... (Dombes Dombes The Dombes is an area in South-Eastern France, once an independent municipality, formerly part of the province of Burgundy, and now a district comprised in the département of Ain, and bounded W. by the Saône River, by the Rhône, E. by the Ain and N... ) Corsica Corsica is an island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is located west of Italy, southeast of the French mainland, and north of the island of Sardinia.... , or Bastia Bastia Bastia is a commune in the Haute-Corse department of France located in the northeast of the island of Corsica at the base of Cap Corse. It is also the second-largest city in Corsica after Ajaccio and the capital of the department.... (Corsica Corsica Corsica is an island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is located west of Italy, southeast of the French mainland, and north of the island of Sardinia.... ) Auch Auch is a commune in southwestern France. Located in the region of Midi-Pyrénées, it is the capital of the Gers department. Auch is the historical capital of Gascony.-The Ausci:... (Gascony Gascony Gascony is an area of southwest France that was part of the "Province of Guyenne and Gascony" prior to the French Revolution. The region is vaguely defined and the distinction between Guyenne and Gascony is unclear; sometimes they are considered to overlap, and sometimes Gascony is considered a... ) Bayonne Bayonne is a city and commune in south-western France at the confluence of the Nive and Adour rivers, in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department, of which it is a sub-prefecture... (Labourd Labourd Labourd is a former French province and part of the present-day Pyrénées Atlantiques département. It is historically one of the seven provinces of the traditional Basque Country.... ) Béarn Béarn is one of the traditional provinces of France, located in the Pyrenees mountains and in the plain at their feet, in southwest France. Along with the three Basque provinces of Soule, Lower Navarre, and Labourd, the principality of Bidache, as well as small parts of Gascony, it forms in the... and Soule Soule Soule is a former viscounty and French province and part of the present day Pyrénées-Atlantiques département... ) |

|

Social history

France in the Ancien Régime covered a territory of around 200000 square miles (517,997.6 km²), and supported 22 million people in 1700. At least 80% of the population were peasants. France had the largest population in Europe, with European Russia second at 20 million. Britain had nearly six million, Spain had eight million, and the Austrian Habsburgs had around eight million. Russia was the most populated European country at the time. France's lead slowly faded after 1700, as other countries grew faster.Rural society

In the 17th century rich peasants who had ties to the market economy provided much of the capital investment necessary for agricultural growth, and frequently moved from village to village (or town). Geographic mobility, directly tied to the market and the need for investment capital, was the main path to social mobility. The "stable" core of French society, town guildspeople and village laboureurs, included cases of staggering social and geographic continuity, but even this core required regular renewal. Accepting the existence of these two societies, the constant tension between them, and extensive geographic and social mobility tied to a market economy holds the key to a clearer understanding of the evolution of the social structure, economy, and even political system of early modern France. Collins (1991) argues that the Annales SchoolAnnales School

The Annales School is a group of historians associated with a style of historiography developed by French historians in the 20th century. It is named after its scholarly journal Annales d'histoire économique et sociale, which remains the main source of scholarship, along with many books and...

paradigm underestimated the role of the market economy; failed to explain the nature of capital investment in the rural economy; and grossly exaggerated social stability.

Women and families

Very few women held any power—some queens did, as did the heads of Catholic convents. In the EnlightenmentAge of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

the writings of philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau gave political program for reform of the ancien régime, founded on a reform of domestic mores. Rousseau's conception of the relations between private and public spheres is more unified than that found in modern sociology. Rousseau argued that the domestic role of women is a structural precondition for a "modern" society.

Salic law prohibited women from rule; however, the laws for the case of a regency, when the king was too young to govern by himself, brought the queen into the center of power. The queen could assure the passage of power from one king to another—from her late husband to her young son—while simultaneously assuring the continuity of the dynasty.

Education for girls

Educational aspirations were on the rise and were becoming increasingly institutionalized in order to supply the church and state with the functionaries to serve as their future administrators. Girls were schooled too, but not to assume political responsibility. Girls were ineligible for leadership positions and were generally considered to have an inferior intellect to their brothers. France had many small local schools where working-class children - both boys and girls - learned to read, the better "to know, love, and serve God." The sons and daughters of the noble and bourgeois elites, however, were given quite distinct educations: boys were sent to upper school, perhaps a university, while their sisters - if they were lucky enough to leave the house - were sent for finishing at a convent. The EnlightenmentAge of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

challenged this model, but no real alternative presented itself for female education. Only through education at home were knowledgeable women formed, usually to the sole end of dazzling their salons.

Stepfamilies

A large proportion of children lived in broken homes or in blended families and had to cope with the presence of half-siblings and stepsiblings in the same residence. Brothers and sisters were often separated during the guardianship period and some of them were raised in different places for most of their childhood. Half-siblings and stepsiblings lived together for rather short periods of time because of their difference in age, their birth rank, or their gender. The lives of the children were closely linked to the administration of their heritage: when both their mothers and fathers were dead, another relative took charge of the guardianship and often removed the children from a stepparent's home, thus separating half-siblings.The experience of step-motherhood was surrounded by negative stereotypes; the Cinderella

Cinderella

"Cinderella; or, The Little Glass Slipper" is a folk tale embodying a myth-element of unjust oppression/triumphant reward. Thousands of variants are known throughout the world. The title character is a young woman living in unfortunate circumstances that are suddenly changed to remarkable fortune...

story and many other jokes and stories made the second wife an object of ridicule. Language, theater, popular sayings, the position of the Church, and the writings of jurists all made stepmother a difficult identity to take up. However, the importance of male remarriage suggests that reconstitution of family units was a necessity and that individuals resisted negative perceptions circulating through their communities. Widowers did not hesitate to take a second wife, and they usually found quite soon a partner willing to become a stepmother. For these women, being a stepmother was not necessarily the experience of a lifetime or what defined their identity. Their experience depended greatly on factors such as the length of the union, changing family configuration, and financial dispositions taken by their husbands.

By a policy adopted at the beginning of the 16th century, adulterous women during the ancien régime were sentenced to a lifetime in a convent unless pardoned by their husbands and were rarely allowed to remarry even if widowed.

State finances

The desire for more efficient tax collection was one of the major causes for French administrative and royal centralization in the early modern period. The tailleTaille

The taille was a direct land tax on the French peasantry and non-nobles in Ancien Régime France. The tax was imposed on each household and based on how much land it held.-History:Originally only an "exceptional" tax The taille was a direct land tax on the French peasantry and non-nobles in Ancien...

became a major source of royal income. Exempted from the taille were clergy and nobles (except for non-noble lands they held in "pays d'état", see below), officers of the crown, military personnel, magistrates, university professors and students, and certain cities ("villes franches") such as Paris.

The provinces were of three sorts, the "pays d'élection", the "pays d'état" and the "pays d'imposition". In the "pays d'élection" (the longest held possessions of the French crown; some of these provinces had had the equivalent autonomy of a "pays d'état" in an earlier period, but had lost it through the effects of royal reforms) the assessment and collection of taxes were trusted to elected officials (at least originally, later these positions were bought), and the tax was generally "personal", meaning it was attached to non-noble individuals. In the "pays d'état" ("provinces with provincial estates"), Brittany

Brittany

Brittany is a cultural and administrative region in the north-west of France. Previously a kingdom and then a duchy, Brittany was united to the Kingdom of France in 1532 as a province. Brittany has also been referred to as Less, Lesser or Little Britain...

, Languedoc

Languedoc

Languedoc is a former province of France, now continued in the modern-day régions of Languedoc-Roussillon and Midi-Pyrénées in the south of France, and whose capital city was Toulouse, now in Midi-Pyrénées. It had an area of approximately 42,700 km² .-Geographical Extent:The traditional...

, Burgundy, Auvergne

Auvergne (province)

Auvergne was a historic province in south central France. It was originally the feudal domain of the Counts of Auvergne. It is now the geographical and cultural area that corresponds to the former province....

, Béarn

Béarn

Béarn is one of the traditional provinces of France, located in the Pyrenees mountains and in the plain at their feet, in southwest France. Along with the three Basque provinces of Soule, Lower Navarre, and Labourd, the principality of Bidache, as well as small parts of Gascony, it forms in the...

, Dauphiné

Dauphiné

The Dauphiné or Dauphiné Viennois is a former province in southeastern France, whose area roughly corresponded to that of the present departments of :Isère, :Drôme, and :Hautes-Alpes....

, Provence

Provence

Provence ; Provençal: Provença in classical norm or Prouvènço in Mistralian norm) is a region of south eastern France on the Mediterranean adjacent to Italy. It is part of the administrative région of Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur...

and portions of Gascony

Gascony

Gascony is an area of southwest France that was part of the "Province of Guyenne and Gascony" prior to the French Revolution. The region is vaguely defined and the distinction between Guyenne and Gascony is unclear; sometimes they are considered to overlap, and sometimes Gascony is considered a...

, such as Bigorre

Bigorre

Bigorre is region in southwest France, historically an independent county and later a French province, located in the upper watershed of the Adour, on the northern slopes of the Pyrenees, part of the larger region known as Gascony...

, Comminges

Comminges

The Comminges is an ancient region of southern France in the foothills of the Pyrenees, corresponding closely to the arrondissement of Saint-Gaudens in the department of Haute-Garonne...

and the Quatre-Vallées

Quatre-Vallées

Quatre-Vallées was a small province of France located in the southwest of France. It was made up of four constituent parts: Aure valley , Barousse valley , Magnoac valley , and Neste or Nestès valley .-General...

, recently acquired provinces which had been able to maintain a certain local autonomy in terms of taxation, the assessment of the tax was established by local councils and the tax was generally "real

Real property

In English Common Law, real property, real estate, realty, or immovable property is any subset of land that has been legally defined and the improvements to it made by human efforts: any buildings, machinery, wells, dams, ponds, mines, canals, roads, various property rights, and so forth...

", meaning that it was attached to non-noble lands (meaning that nobles possessing such lands were required to pay taxes on them). "Pays d'imposition" were recently conquered lands which had their own local historical institutions (they were similar to the "pays d'état" under which they are sometimes grouped), although taxation was overseen by the royal intendant

Intendant

The title of intendant has been used in several countries through history. Traditionally, it refers to the holder of a public administrative office...

.

Taxation districts had gone through a variety of mutations from the 14th century on. Before the 14th century, oversight of the collection of royal taxes fell generally to the bailli

Bailli

A bailli was the king’s administrative representative during the ancien régime in northern France, where the bailli was responsible for the application of justice and control of the administration and local finances in his baillage...

s and sénéchaux in their circumscriptions. Reforms in the 14th and 15th centuries saw France's royal financial administration run by two financial boards which worked in a collegial manner: the four Généraux des finances (also called "général conseiller" or "receveur général" ) oversaw the collection of taxes (taille

Taille

The taille was a direct land tax on the French peasantry and non-nobles in Ancien Régime France. The tax was imposed on each household and based on how much land it held.-History:Originally only an "exceptional" tax The taille was a direct land tax on the French peasantry and non-nobles in Ancien...

, aides, etc.) by tax-collecting agents (receveurs) and the four Trésoriers de France (Treasurers) oversaw revenues from royal lands (the "domaine royal

Crown lands of France

The crown lands, crown estate, royal domain or domaine royal of France refers to the lands, fiefs and rights directly possessed by the kings of France...

"). Together they were often referred to as "Messieurs des finances". The four members of each board were divided by geographical circumscriptions (although the term "généralité" isn't found before the end of the 15th century); the areas were named Languedoïl, Languedoc, Outre-Seine-and-Yonne, and Nomandy (the latter was created in 1449; the other three were created earlier), with the directors of the "Languedoïl" region typically having an honorific preeminence. By 1484, the number of généralités had increased to 6.

In the 16th century, the kings of France, in an effort to exert more direct control over royal finances and to circumvent the double-board (accused of poor oversight) -- instituted numerous administrative reforms, including the restructuring of the financial administration and an increase in the number of "généralités". In 1542, Henry II

Henry II of France

Henry II was King of France from 31 March 1547 until his death in 1559.-Early years:Henry was born in the royal Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, near Paris, the son of Francis I and Claude, Duchess of Brittany .His father was captured at the Battle of Pavia in 1525 by his sworn enemy,...

, France was divided into 16 "généralités". The number increased to 21 at the end of the 16th century, and to 36 at the time of the French Revolution; the last two were created in 1784.

The administration of the généralités of the Renaissance went through a variety of reforms. In 1577, Henry III

Henry III of France

Henry III was King of France from 1574 to 1589. As Henry of Valois, he was the first elected monarch of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth with the dual titles of King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1573 to 1575.-Childhood:Henry was born at the Royal Château de Fontainebleau,...

established 5 treasurers ("trésoriers généraux") in each généralité who formed a bureau of finances. In the 17th century, oversight of the généralités was subsumed by the intendant

Intendant

The title of intendant has been used in several countries through history. Traditionally, it refers to the holder of a public administrative office...

s of finance, justice and police, and the expression "généralité" and "intendance" became roughly synonymous.

Until the late 17th century, tax collectors were called receveurs. In 1680, the system of the Ferme Générale

Ferme générale

The Ferme générale was, in ancien régime France, essentially an outsourced customs and excise operation which collected duties on behalf of the king, under six-year contracts...

was established, a franchised customs and excise operation in which individuals bought the right to collect the taille on behalf of the king, through 6-years adjudications (certain taxes like the aides and the gabelle had been farmed out in this way as early as 1604). The major tax collectors in that system were known as the fermiers généraux (farmers-general in English).

The taille was only one of a number of taxes. There also existed the "taillon" (a tax for military purposes), a national salt tax (the gabelle

Gabelle

The gabelle was a very unpopular tax on salt in France before 1790. The term gabelle derives from the Italian gabella , itself from the Arabic qabala....

), national tariffs (the "aides") on various products (wine, beer, oil, and other goods), local tariffs on speciality products (the "douane") or levied on products entering the city (the "octroi") or sold at fairs, and local taxes. Finally, the church benefited from a mandatory tax or tithe

Tithe

A tithe is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash, cheques, or stocks, whereas historically tithes were required and paid in kind, such as agricultural products...

called the "dîme".

Louis XIV

Louis XIV of France

Louis XIV , known as Louis the Great or the Sun King , was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and Navarre. His reign, from 1643 to his death in 1715, began at the age of four and lasted seventy-two years, three months, and eighteen days...

created several additional tax systems, including the "capitation" (begun in 1695) which touched every person including nobles and the clergy (although exemption could be bought for a large one-time sum) and the "dixième" (1710–1717, restarted in 1733), enacted to support the military, which was a true tax on income and on property value. In 1749, under Louis XV

Louis XV of France

Louis XV was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and of Navarre from 1 September 1715 until his death. He succeeded his great-grandfather at the age of five, his first cousin Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, served as Regent of the kingdom until Louis's majority in 1723...

, a new tax based on the "dixième", the "vingtième" (or "one-twentieth"), was enacted to reduce the royal deficit, and this tax continued through the remaining years of the ancien régime.

Another key source of state financing was through charging fees for state positions (such as most members of parlements, magistrates, maître des requêtes

Maître des requêtes

Masters of Requests are high-level judicial officers of administrative law in France and other European countries that have existed in one form or another since the Middle Ages.-Old Regime France:...

and financial officers). Many of these fees were quite elevated, but some of these offices conferred nobility and could be financially advantageous. The use of offices to seek profit had become standard practice as early as the 12th and 13th centuries. A law in 1467 made these offices unrevocable, except through the death, resignation or forfeiture of the title holder, and these offices, once bought, tended to become hereditary charges (with a fee for transfer of title) passed on within families. In an effort to increase revenues, the state often turned to the creation of new offices. Before it was made illegal in 1521, It had been possible to leave open-ended the date that the transfer of title was to take effect. In 1534, the "forty days rule" was instituted (adapted from church practice), which made the successor's right void if the preceding office holder died within forty days of the transfer and the office returned to the state;however, a new fee, called the survivance jouissante protected against the forty days rule. In 1604, Sully

Maximilien de Béthune, duc de Sully

Maximilien de Béthune, first Duke of Sully was the doughty soldier, French minister, staunch Huguenot and faithful right-hand man who assisted Henry IV of France in the rule of France.-Early years:...

created a new tax, the "paulette

Paulette

La Paulette was the name commonly given to the "annual right" , a special tax levied by the French Crown during the Ancien Régime. It was first instituted on December 12, 1604 by King Henry IV's minister Maximilien de Béthune, duc de Sully...

" or "annual tax" (1/60 of the amount of the official charge), which permitted the title-holder to be free of the 40 day rule. The "paulette" and the venality of offices became key concerns in the parlementarian revolts of the 1640s (La Fronde

La Fronde

La Fronde was a French feminist newspaper first published in Paris on December 9, 1897 by activist Marguerite Durand . Durand, a well known actress and journalist, used her high-profile image to attract many notable Parisian women to contribute articles to her daily newspaper, which was run and...

).

The state also demanded of the church a "free gift", which the church collected from holders of eccleciastic offices through taxes called the "décime" (roughly 1/20th of the official charge, created under Francis I).

State finances also relied heavily on borrowing, both private (from the great banking families in Europe) and public. The most important public source for borrowing was through the system of rentes sur l'Hôtel de Ville of Paris, a kind of government bond system offering investers annual interest. This system first came to use in 1522 under Francis I.

Until 1661, the head of the financial system in France was generally the surintendant des finances; with the fall of Fouquet

Fouquet

Fouquet is a French surname and may refer to:* Charles Louis Auguste Fouquet, duc de Belle-Isle , French general and statesman* Guillaume Fouquet de la Varenne , French chef and statesman...

, this was replaced by the lesser position of contrôleur général des finances.

For more information on the Ancien Régime economy, see Economic history of France

Economic history of France

This is a history of the economy of France. For more information on historical, cultural, demographic and sociological developments in France, see the chronological era articles in the template to the right...

.

Lower courts

Justice in seigneurial lands (including those held by the church or within cities) was generally overseen by the seigneur or his delegated officers. Since the 15th century, much of the seigneur's legal purview had been given to the bailliages or sénéchaussées and the présidiaux (see below), leaving only affairs concerning seigeurial dues and duties, and small affairs of local justice. Only certain seigneurs—those with the power of haute justice (seigeurial justice was divided into "high" "middle" and "low" justice) -- could enact the death penalty, and only with the consent of the présidiaux.Crimes of desertion, highway robbery, and mendicants (so-called cas prévôtaux) were under the supervision of the prévôt des maréchaux, who exacted quick and impartial justice. In 1670, their purview was overseen by the présidiaux (see below).

The national judicial system was made-up of tribunals divided into bailli

Bailli

A bailli was the king’s administrative representative during the ancien régime in northern France, where the bailli was responsible for the application of justice and control of the administration and local finances in his baillage...