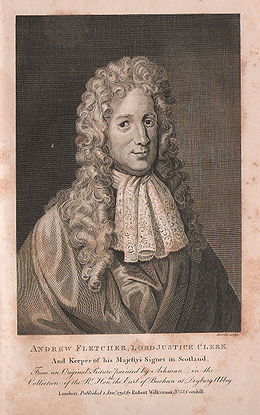

Andrew Fletcher

Encyclopedia

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

writer, politician, soldier and patriot. He was a Commissioner

Commissioner

Commissioner is in principle the title given to a member of a commission or to an individual who has been given a commission ....

of the old Parliament of Scotland

Parliament of Scotland

The Parliament of Scotland, officially the Estates of Parliament, was the legislature of the Kingdom of Scotland. The unicameral parliament of Scotland is first found on record during the early 13th century, with the first meeting for which a primary source survives at...

and is remembered as the leading opponent of the 1707 Act of Union

Acts of Union 1707

The Acts of Union were two Parliamentary Acts - the Union with Scotland Act passed in 1706 by the Parliament of England, and the Union with England Act passed in 1707 by the Parliament of Scotland - which put into effect the terms of the Treaty of Union that had been agreed on 22 July 1706,...

between Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

and England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

and an advocate of the Darién scheme

Darién scheme

The Darién scheme was an unsuccessful attempt by the Kingdom of Scotland to become a world trading nation by establishing a colony called "New Caledonia" on the Isthmus of Panama in the late 1690s...

, he also introduced agricultural improvements to Scotland

Early life and political career

Andrew Fletcher was the son and heir of Sir Robert Fletcher (1625–1664), and was born at SaltounEast Saltoun and West Saltoun

East Saltoun and West Saltoun are separate villages in East Lothian, Scotland, about 5 miles south-west of Haddington and 20 miles east of Edinburgh.- Geography :...

in Haddingtonshire. Educated by Gilbert Burnet

Gilbert Burnet

Gilbert Burnet was a Scottish theologian and historian, and Bishop of Salisbury. He was fluent in Dutch, French, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. Burnet was respected as a cleric, a preacher, and an academic, as well as a writer and historian...

, the future Bishop of Salisbury

Bishop of Salisbury

The Bishop of Salisbury is the ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of Salisbury in the Province of Canterbury.The diocese covers much of the counties of Wiltshire and Dorset...

, who was then minister at Saltoun, he completed his education in mainland Europe. Fletcher was elected, as the Commissioner for Haddingtonshire, to the Scottish Parliament in 1678. At this time, Charles II's representative in Scotland was John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale

John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale

Sir John Maitland, 1st Duke and 2nd Earl of Lauderdale, 3rd Lord Thirlestane KG PC , was a Scottish politician, and leader within the Cabal Ministry.-Background:...

. The Duke had taxation powers in Scotland, and maintained a standing army there in the name of the King. Fletcher bitterly opposed the Duke, whose actions only strengthened Fletcher's distrust of the royal government in Scotland, as well as all hereditary power. In 1681, Fletcher was re-elected to the Scottish Parliament as member for Haddingtonshire. The year before, Lauderdale had been replaced by the Duke of Albany

James II of England

James II & VII was King of England and King of Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII, from 6 February 1685. He was the last Catholic monarch to reign over the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland...

. At this time, Fletcher was a member of the opposition Country Party in the Scottish Parliament, where he resolutely opposed any arbitrary actions on the part of the Church or state.

Exile and return

In 1683, after being charged with sedition and being acquitted, Fletcher fled Scotland to join with English opponents of King Charles in the NetherlandsNetherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

where he joined James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth

James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth

James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, 1st Duke of Buccleuch, KG, PC , was an English nobleman. Originally called James Crofts or James Fitzroy, he was born in Rotterdam in the Netherlands, the eldest illegitimate son of Charles II and his mistress, Lucy Walter...

's rebellion. Landing in Dorset Fletcher - who was to command the cavalry - appropriated a fine horse belonging to leading sympathizer Thomas Dare who furiously demanded that he dismount; Dare threateningly raised a cane whereupon Fletcher shot him dead. This ended his involvement with the doomed rebellion and almost certainly saved his life. He again left the country and after escaping from a Spanish prison fought in Hungary against the Turks before joining William of Orange

William III of England

William III & II was a sovereign Prince of Orange of the House of Orange-Nassau by birth. From 1672 he governed as Stadtholder William III of Orange over Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel of the Dutch Republic. From 1689 he reigned as William III over England and Ireland...

in the Netherlands. Fletcher returned to Scotland in 1688 but his alliance with the Prince of Orange faded when it became clear William II - as he was in Scotland - was only interested in using the country to help fight foreign wars. His estates were restored to him and, increasingly, Fletcher defended his country's claims over English interests as well as opposing royal power. In 1703, at a critical stage in the history of Scotland, Fletcher again became a member of the Scottish Parliament as member for Haddingtonshire. Now Queen Anne

Anne of Great Britain

Anne ascended the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland on 8 March 1702. On 1 May 1707, under the Act of Union, two of her realms, England and Scotland, were united as a single sovereign state, the Kingdom of Great Britain.Anne's Catholic father, James II and VII, was deposed during the...

was on the throne and there was a campaign to join England and Scotland in a parliamentary union, thus closing the "back door" to England that Scotland represented.

Darién Scheme and the Act of Union

Fletcher had been a early supporter of the Darien expeditionDarién scheme

The Darién scheme was an unsuccessful attempt by the Kingdom of Scotland to become a world trading nation by establishing a colony called "New Caledonia" on the Isthmus of Panama in the late 1690s...

, a financial disaster at the worst possible time for a country which had suffered repeated bad harvests and he continued to defend the Darién scheme against those - including agents of the English - who painted it as an act of folly. Hurt national pride had led to many Scots blaming the scheme's failure on the hostility of England, Fletcher and the Country party seized the opportunity to promote Scottish independence. However, by practically ruining the political elite the Darién scheme

Darién scheme

The Darién scheme was an unsuccessful attempt by the Kingdom of Scotland to become a world trading nation by establishing a colony called "New Caledonia" on the Isthmus of Panama in the late 1690s...

had weakened resistance to England's plans for a Union - and offers of money to Scots who would support it. Fletcher continued to argue against an 'incorporating union' and for a federal union to protect Scotland's nationhood. Although not successful in preventing the Act of Union

Acts of Union 1707

The Acts of Union were two Parliamentary Acts - the Union with Scotland Act passed in 1706 by the Parliament of England, and the Union with England Act passed in 1707 by the Parliament of Scotland - which put into effect the terms of the Treaty of Union that had been agreed on 22 July 1706,...

passing in the Scottish parliament through these debates Fletcher gained recognition as an independent patriot.

One of his most famous contributions were his "twelve limitations," intended to limit the power of the crown and English ministers in Scottish politics. His limitations were:

- THAT elections shall be made at every MichaelmasMichaelmasMichaelmas, the feast of Saint Michael the Archangel is a day in the Western Christian calendar which occurs on 29 September...

head-court for a new Parliament every year; to sit the first of November next following, and adjourn themselves from time to time, till next Michaelmas; That they choose their own president, and that everything shall be determined by balloting, in place of voting. - THAT so many lesser barons shall be added to the Parliament, as there have been noblemen created since the last augmentation of the number of the barons; and that in all time coming, for every nobleman that shall be created, there shall be a baron added to the Parliament.

- THAT no man have vote in Parliament, but a nobleman or elected member.

- THAT the King shall give the sanction to all laws offered by the Estates; and that the president of the Parliament be empowered by His Majesty to give the sanction in his absence, and have ten pounds sterling a day salary.

- THAT a committee of one and thirty members, of which nine to be a quorum, chosen out of their own number, by every Parliament, shall, during the intervals of Parliament, under the King, have the administration of the government, be his council, and accountable to the next Parliament; with power in extraordinary occasions, to call the Parliament together; and that in the said council, all things be determined by ballotting in place of voting.

- THAT the King without consent of Parliament shall not have the power of making peace and war; or that of concluding any treaty with any other state or potentate.

- THAT all places and offices, both civil and military, and all pensions formerly conferred by our Kings shall ever after be given by Parliament.

- THAT no regiment or company of horse, foot or dragoons, be kept on foot in peace or war, but by consent of Parliament.

- THAT all fencible men of the nation, between sixty and sixteen, be with all diligence possible armed with bayonets, and firelocks all of a calibre, and continue always provided in such arms with ammunition suitable.

- THAT no general indemnity, nor pardon for any transgression against the public, shall be valid without consent of Parliament.

- THAT the fifteen Senators of the College of Justice shall be incapable of being members of Parliament, or of any other office, or any pension; but the salary that belongs to their place to be increased as the Parliament shall think fit; that the office of PresidentLord President of the Court of SessionThe Lord President of the Court of Session is head of the judiciary in Scotland, and presiding judge of the College of Justice and Court of Session, as well as being Lord Justice General of Scotland and head of the High Court of Justiciary, the offices having been combined in 1836...

shall be in three of their number to be named by Parliament, and that there be no extraordinary lordsExtraordinary Lord of SessionExtraordinary Lords of Session were lay members of the Court of Session in Scotland from 1532 to 1762.When the Court of Session was founded in 1532, it consisted of the Lord President, 14 Ordinary Lords and three or four Extraordinary Lords. The Extraordinary Lords were nominees of the King, not...

, and also, that the lords of the Justice courtHigh Court of JusticiaryThe High Court of Justiciary is the supreme criminal court of Scotland.The High Court is both a court of first instance and a court of appeal. As a court of first instance, the High Court sits mainly in Parliament House, or in the former Sheriff Court building, in Edinburgh, but also sits from time...

shall be distinct from those of the SessionCourt of SessionThe Court of Session is the supreme civil court of Scotland, and constitutes part of the College of Justice. It sits in Parliament House in Edinburgh and is both a court of first instance and a court of appeal....

, and under the same restrictions. - THAT if any King break in upon any of these conditions of government, he shall by the Estates be declared to have forfeited the crown.

Although the limitations did not pass the house, something little short of them was passed, the Act of Security, which made provisions in case of the Queen’s death, with the conditions under which the successor to the crown of England was to be allowed to succeed to that of Scotland, which were to be, "at least, freedom of navigation, free communication of trade, and liberty of the plantations to the kingdom and subjects of Scotland, established by the parliament of England." The same parliament passed an Act anent Peace and War, which provided that after Queen’s death, failing heirs of her body, no person at the same time being King or Queen of Scotland and England, would have sole power of making war without consent of the Scottish Parliament.

Withdrawal from politics

In 1707, the Act of Union was approved by the Scottish Parliament, officially uniting Scotland with EnglandEngland

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

to form the Kingdom of Great Britain

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

. Fletcher turned from politics in despair and devoted the rest of his life to farming and agricultural development in Scotland. He died unmarried in London in September 1716. His last words were 'Lord have mercy on my poor country that is so barbarously oppressed.'

Reputation

He was reputed to have the best private library in Scotland. Contemporaries thought very highly of Fletcher's integrity, but he was also seen as impetuous, some Englishmen regarded him as a violent, ingenious fanatic. Arthur Herman in his How the Scots Invented the Modern WorldHow the Scots Invented the Modern World

How the Scots Invented the Modern World: The true story of how western Europe's poorest nation created our world & everything in it is a non-fiction book written by Arthur Herman. The book examines the origins of the Scottish Enlightenment and what impact it had on the modern world...

describes Fletcher as a genuine intellectual but regards his vision for Scotland as retrograde and cites his suggestion military training should be conducted in camps where - No woman should be suffered to come within the camp, and the crimes of abusing their own bodies any manner of way, punished with death. Burnet

Gilbert Burnet

Gilbert Burnet was a Scottish theologian and historian, and Bishop of Salisbury. He was fluent in Dutch, French, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. Burnet was respected as a cleric, a preacher, and an academic, as well as a writer and historian...

describes him as "a Scotch

Scottish people

The Scottish people , or Scots, are a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland. Historically they emerged from an amalgamation of the Picts and Gaels, incorporating neighbouring Britons to the south as well as invading Germanic peoples such as the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse.In modern use,...

gentleman of great parts and many virtues, but a most violent republican

Republicanism

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context...

and extremely passionate". Alasdair MacIntyre

Alasdair MacIntyre

Alasdair Chalmers MacIntyre is a British philosopher primarily known for his contribution to moral and political philosophy but known also for his work in history of philosophy and theology...

has written that "Almost alone among his contemporaries Fletcher understood the dilemma confronting Scotland as involving more radical

Radicalism (historical)

The term Radical was used during the late 18th century for proponents of the Radical Movement. It later became a general pejorative term for those favoring or seeking political reforms which include dramatic changes to the social order...

alternatives than they were prepared to entertain".

Main works

His chief works are A Discourse of Government relating to Militias (1698), in which he argued that the royal army in Scotland should be replaced by local militias - a position of republican virtue which was to return a half-century later and foreshadowed the thinking of Adam FergusonAdam Ferguson

Adam Ferguson FRSE, also known as Ferguson of Raith was a Scottish philosopher, social scientist and historian of the Scottish Enlightenment...

in lauding martial virtues over commercially minded polite society which he thought unmanly.

Two Discourses concerning the Affairs of Scotland (1698), in which he discussed the problems of Scottish trade and economics; and An Account of a Conversation concerning a right regulation of Governments for the common good of Mankind (1703). In Two Discourses he suggested that the numerous vagrants who infested Scotland should be brought into compulsory and hereditary servitude, it was already the case that criminals or the dissolute were transported to the colonies and sold as virtual slaves at that time. In An Account of a Conversation he made his well-known remark "I knew a very wise man so much of Sir Christopher's sentiment, that he believed if a man were permitted to make all the ballad

Ballad

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads were particularly characteristic of British and Irish popular poetry and song from the later medieval period until the 19th century and used extensively across Europe and later the Americas, Australia and North Africa. Many...

s, he need not care who should make the laws of a nation."

In Fiction

- Tranter, NigelNigel TranterNigel Tranter OBE was a Scottish historian and author.-Early life:Nigel Tranter was born in Glasgow and educated at George Heriot's School in Edinburgh. He trained as an accountant and worked in Scottish National Insurance Company, founded by his uncle. In 1933 he married May Jean Campbell Grieve...

(1994). The Patriot. London: Trafalgar Square. ISBN 0-3403-4915-8.