Anglo-Irish Treaty

Encyclopedia

The Anglo-Irish Treaty , officially called the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was a treaty

between the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

and representatives of the secessionist Irish Republic

that concluded the Irish War of Independence

. It established the Irish Free State

as a self-governing dominion

within the British Empire

and also provided Northern Ireland

, which had been created by the Government of Ireland Act 1920

, an option to opt out of the Irish Free State, which it exercised.

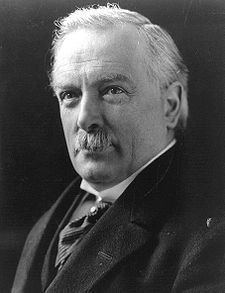

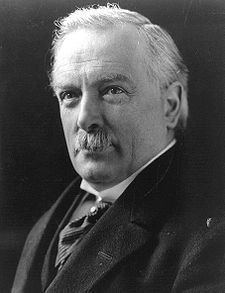

The treaty was signed in London on 6 December 1921 by representatives of the British government (which included David Lloyd George

, who was head of the British delegates) and envoys of the Irish Republic, including Michael Collins

and Arthur Griffith

, who claimed plenipotentiary

status (i.e. negotiators empowered to sign a treaty without reference back to their superiors). In accordance with its terms the Treaty needed to be and was ratified by the members elected to sit in the House of Commons of Southern Ireland and the British Parliament. Dáil Éireann

for the de facto Irish Republic also ratified the Treaty (narrowly). Though the treaty was duly ratified, the split led to the Irish Civil War

, which was ultimately won by the pro-treaty side.

The Irish Free State created by the Treaty came into force on 6 December 1922 by royal proclamation after its constitution had been enacted by the Provisional parliament of Southern Ireland (also styled the Third Dail

) and the British parliament.

Among the Treaty's main clauses were that:

Among the Treaty's main clauses were that:

The negotiators included:

The negotiators included:

(Robert Erskine Childers

, the author of the Riddle of the Sands and former Clerk of the British House of Commons, served as one of the secretaries of the Irish delegation. Tom Jones

was one of Lloyd George's principal assistants, and described the negotiations in his book Whitehall Diary.)

Notably, the Irish President Éamon de Valera

did not attend.

Winston Churchill

had a dual role in the British cabinet concerning the Treaty: firstly as Secretary for War hoping to end the Irish War of Independence

in 1921; then in 1922, as Secretary for the Colonies (which included Dominion affairs) he was charged with implementing it.

Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera

sent the Irish plenipotentiaries to the 1921 negotiations in London with several draft treaties and secret instructions from his cabinet. Pointedly the British side never asked to see their formal accreditation with the full status of plenipotentiaries, but considered that it had invited them as elected MPs: "...to ascertain how the association of Ireland with the community of nations known as the British Empire can best be reconciled with Irish national aspirations". This initial invitation in August had been delayed for over a month by a correspondence in which De Valera argued that Britain was now negotiating with a sovereign state, a position Lloyd George continually denied.

In the meantime, De Valera had been elevated to President of the Republic on 26 August, primarily to be able to accredit plenipotentiaries for the negotiations, as is usual between sovereign states. On 14 September all the Dáil speakers unanimously commented that the plenipotentiaries were being sent to represent the sovereign Irish Republic, and accepted De Valera's nominations without dissent.

On 18 September Lloyd-George recalled that "From the very outset of our conversations [in June 1921] I told you that we looked to Ireland to own allegiance to the Throne, and to make her future as a member of the British Commonwealth. That was the basis of our proposals, and we cannot alter it. The status which you now claim in advance for your delegates is, in effect, a repudiation of that basis. I am prepared to meet your delegates as I met you in July, in the capacity of ‘chosen spokesmen’ for your people, to discuss the association of Ireland with the British Commonwealth."

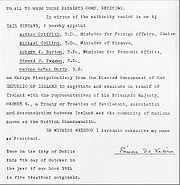

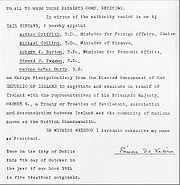

On 7 October De Valera signed the letter of accreditation as "President" on behalf of the "Government of the Republic of Ireland" (see image), but the letter was never requested in the usual diplomatic manner. The original invitation was finally repeated unaltered by Lloyd-George on 11 October, and was tacitly accepted as such by the Irish side. Both the Irish and British sides knew that, in the event of failure, the truce agreed in July 1921 would end and the war would inevitably resume, a war that neither side wanted. Three months had passed by with nothing agreed.

The ambiguous status of the plenipotentiaries was to have unforeseeable consequences within the Nationalist movement when it divided over the Treaty's contents in 1921–22. Subsequently, the anti-treaty side felt that the plenipotentiaries from the existing sovereign republic had somehow been persuaded to agree to accept much less. The pro-treaty side was to argue that after 11 October the negotiations had been conducted on the understanding that, even though the British were not negotiating with a sovereign state, the agreement was a significant first step towards Irish sovereignty. Further, the pro-treaty side argued that the status of plenipotentiary as granted by the Dáil had given them full powers to handle negotiations as they saw fit, without the need to refer back to Dublin on every point.

Days after the Truce that ended the Anglo-Irish War, De Valera met Lloyd George in London four times in the week starting 14 July. Lloyd George sent his initial proposals on 20 July that were very roughly in line with the Treaty that was eventually signed. This was followed by months of delay until October, when the Irish delegates set up headquarters in 22 Hans Place

Days after the Truce that ended the Anglo-Irish War, De Valera met Lloyd George in London four times in the week starting 14 July. Lloyd George sent his initial proposals on 20 July that were very roughly in line with the Treaty that was eventually signed. This was followed by months of delay until October, when the Irish delegates set up headquarters in 22 Hans Place

, Knightsbridge

.

The first two weeks of the negotiations were spent in formal sessions. Upon the request of Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins, the two delegations began informal negotiations, in which only two members of each negotiating team were allowed to attend. On the Irish side, these members were always Collins and Griffith, while on the British side, Austin Chamberlain always attended, though the second British negotiator would vary from day to day. In late November, the Irish delegation returned to Dublin to consult the cabinet according to their instructions, and again on 3 December. Many points still had to be resolved, mainly surrounding the form of an oath to the monarch, but it was clear to all the politicians involved by this stage that a unitary 32-county Irish republic was not on offer.

When they returned, Collins and Griffith hammered out the final details of the treaty, which included British concessions on the wording of the oath and the defence and trade clauses, along with the addition of a Boundary Commission to the treaty and a clause upholding Irish unity. Collins and Griffith in turn convinced the other plenipotentiaries to sign the treaty. The final decisions to sign the Treaty was made in private discussions at 22 Hans Place

at 11.15am on 5 December 1921. Negotiations closed by signing on at 2.20am 6 December 1921.

Michael Collins later claimed that at the last minute Lloyd George threatened the Irish delegates with a renewal of "terrible and immediate war" if the Treaty was not signed at once, but this was not mentioned as a threat in the Irish memorandum about the close of negotiations, merely a reflection of the reality. Robert Barton noted that:

Éamon de Valera called a cabinet meeting to discuss the treaty on 8 December, where he came out against the treaty as signed. The cabinet decided by 4 votes to 3 to recommend the Treaty to the Dáil on 14 December.

.jpg) The contents of the Treaty divided the Irish Republic's leadership, with the President of the Republic

The contents of the Treaty divided the Irish Republic's leadership, with the President of the Republic

, Éamon de Valera, leading the anti-Treaty minority. The Treaty Debates

were difficult but also comprised a wider and robust stock-taking of the position by the contending parties. Their differing views of the past and their hopes for the future were made public. The focus had to be on the constitutional options, but little mention was made of the economy, nor of how life would now be improved for the majority of the population. Though Sinn Féin

had also campaigned to preserve the Irish language

, very little use was made of it in the debates. Some of the female TDs were notably in favour of continuing the war until a 32-county state was established. Much mention was made of '700 years' of British occupation. Personal bitterness developed; Arthur Griffith said of Erskine Childers

: "I will not reply to any damned Englishman in this Assembly" and Cathal Brugha

reminded everyone that the position of Michael Collins in the IRA was technically inferior to his.

The main dispute was centred on the status as a dominion (as represented by the Oath of Allegiance and Fidelity) rather than as an independent republic

, but partition was a significant matter for dissent. Ulstermen like Sean MacEntee

spoke strongly against the partition clause. The Dáil voted to approve the Treaty but the objectors refused to accept it, leading eventually to the Irish Civil War

. McEntee was among their leaders.

On 11 July 1924, the treaty was registered at the League of Nations

by the Irish Free State.

However when the Treaty was ratified by the Dáil on 7 January, he refused to accept the vote as final.

Secret sessions were held on 14–17 December, and on the morning of 6 January, to keep the discord out of the press and the public arena. During the first of these, De Valera also produced his ideal redraft, which was not in most respects radically different from the signed agreement, but which was probably not acceptable to the British side as the differing points had already been explored.

On 15 December, Robert Barton was questioned by Kevin O'Higgins

about his notes on Lloyd George's statement about signing the agreement or facing a renewal of war: "Did Mr. Lloyd George single Mr. Barton out as the left wing of the delegation and did he say, “The man who is against peace may bear now and forever the responsibility for terrible and immediate war?"" Barton replied: "What he did say was that the signature and the recommendation of every member of the delegation was necessary, or war would follow immediately and that the responsibility for that war must rest directly upon those who refused to sign the Treaty". This was seized upon by opponents of the Treaty as a convenient proof that the Irish delegates had been subjected to duress

at the last minute, and "terrible and immediate war" became a catch-phrase in the debates that followed. The next day, De Valera took up this point: "... therefore what happened was that over there a threat of immediate force upon our people was made. I believe that that document was signed under duress and, though I have a moral feeling that any agreement entered into ought to be faithfully carried out, I have no hesitation in saying that I would not regard it as binding on the Irish nation."

The crucial private Dáil session on 6 January was informed that it could not be told about a private conference of 9 TDs that had reached a compromise agreement on almost all points the night before. Most TDs wanted at least to be told what matters were still not agreed on, and from this point onwards the pro-Treaty members insisted that all sessions should be held in public.

The public sessions lasted 9 days from 19 December to 7 January. On 19 December Arthur Griffith moved:

"That Dáil Éireann approves of the Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, signed in London on 6 December 1921."

By 6 January, the day before the final vote, de Valera acknowledged the deep division within his cabinet: "When these Articles of Agreement were signed, the body in which the executive authority of this assembly, and of the State, is vested became as completely split as it was possible for it to become. Irrevocably, not on personalities or anything of that kind or matter, but on absolute fundamentals."

The Second Dáil

formally ratified the Treaty on 7 January 1922 by a vote of 64 to 57. De Valera resigned as President on 9 January and was replaced by Arthur Griffith, on a vote of 60 to 58. On 10 January, De Valera published his second redraft, known generally as "Document No. 2".

Griffith, as President of the Dáil, worked with Michael Collins, who chaired the new Provisional Government of Ireland, theoretically answerable to the House of Commons of Southern Ireland, as the Treaty laid down. In December 1922, a new Irish constitution was enacted by the Third Dáil

, sitting as a Constituent Assembly

, providing the legal basis for the Irish Free State

.

At "a meeting of members of the Parliament elected for constituencies in Southern Ireland" (though not the House of Commons of Southern Ireland – see this), as provided for in the Treaty to, did so unanimously on 14 January 1922.

The split over the Treaty eventually led to the Irish Civil War

The split over the Treaty eventually led to the Irish Civil War

(1922–23). In 1922 its two main Irish signatories, President Griffith and Michael Collins, both died. Griffith died partially from exhaustion; Collins, at the signing of the Treaty, had said that in signing it, he may have signed his "actual death warrant"– and he was correct: he was assassinated by anti-Treaty republicans in Béal na mBláth in August 1922, barely a week after Griffith's death. Both men were replaced in their posts by W. T. Cosgrave. Two of the other members of the delegation, Robert Barton and Erskine Childers sided against the Treaty in the civil war. Childers, head of Anti-Treaty propaganda in the conflict, was executed by the Free State for possession of a pistol in November 1922.

The Treaty's provisions relating to the monarch, the governor-general, and the treaty's own superiority in law were all deleted from the Constitution of the Irish Free State in 1932, following the enactment of the Statute of Westminster

by the British Parliament. By this Statute, the British Parliament voluntarily relinquished its ability to legislate on behalf of dominions without their consent. Thus, the Government of the Irish Free State was free to change any laws previously passed by the British Parliament on their behalf.

Nearly 10 years earlier, Michael Collins had argued that the Treaty would give "the freedom to achieve freedom". De Valera himself acknowledged the accuracy of this claim both in his actions in the 1930s but also in words he used to describe his opponents and their securing of independence during the 1920s. "They were magnificent", he told his son in 1932, just after he had entered government and read the files left by Cosgrave's Cumann na nGaedheal Executive Council.

Although the British government of the day had, since 1914, desired home rule

for the whole of Ireland, the British Parliament believed that it could not possibly grant complete independence to all of Ireland in 1921 without provoking a massacre of Ulster

Catholics at the hands of their heavily armed Protestant Unionist neighbours. At the time, although there were Unionists throughout the country, they were concentrated in the northeast and their parliament first sat on 7 June 1921. An uprising by them against home rule would have been an insurrection against the "mother county" as well as a civil war in Ireland. (See Ulster Volunteer Force). Dominion status for 26 counties, with partition for the six counties that the Unionists felt they could comfortably control, seemed the best compromise possible at the time.

In fact, what Ireland received in dominion status, on par with that enjoyed by Canada, New Zealand and Australia, was far more than the Home Rule Act 1914

, and certainly a considerable advance on the Home Rule

once offered to Charles Stewart Parnell

in the nineteenth century. Even de Valera's proposals made in secret during the Treaty Debates differed very little in essential matters from the accepted text, and were far short of the autonomous 32-county republic that he publicly claimed to pursue.

The solution that was agreed had also been on Lloyd George's mind for years. He met Tim Healy, a senior barrister and former nationalist MP, in late 1919 to consider his options. Healy wrote to his brother on 11 December 1919: "Lloyd George said that, if he could get support for a plan whereby the six counties would be left as they are, he would be ready to give the rest of the country Dominion Home Rule, free from Imperial taxation, and with control of the Customs and Excise." Healy considered that the idea had foundered on de Valera's insistence on having an all-Ireland republic, months before the War of Independence became seriously violent in mid-1920.

Lloyd George had supported the 1893 Home Rule Bill

and the slow process of the 1914 Home Rule Act, and liaised with the Irish Convention

members in 1917–18. By 1921 his coalition government depended on a large Conservative majority, and collapsed during the Chanak crisis

in October 1922.

Treaty

A treaty is an express agreement under international law entered into by actors in international law, namely sovereign states and international organizations. A treaty may also be known as an agreement, protocol, covenant, convention or exchange of letters, among other terms...

between the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

and representatives of the secessionist Irish Republic

Irish Republic

The Irish Republic was a revolutionary state that declared its independence from Great Britain in January 1919. It established a legislature , a government , a court system and a police force...

that concluded the Irish War of Independence

Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence , Anglo-Irish War, Black and Tan War, or Tan War was a guerrilla war mounted by the Irish Republican Army against the British government and its forces in Ireland. It began in January 1919, following the Irish Republic's declaration of independence. Both sides agreed...

. It established the Irish Free State

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State was the state established as a Dominion on 6 December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed by the British government and Irish representatives exactly twelve months beforehand...

as a self-governing dominion

Dominion

A dominion, often Dominion, refers to one of a group of autonomous polities that were nominally under British sovereignty, constituting the British Empire and British Commonwealth, beginning in the latter part of the 19th century. They have included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland,...

within the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

and also provided Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

, which had been created by the Government of Ireland Act 1920

Government of Ireland Act 1920

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 was the Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which partitioned Ireland. The Act's long title was "An Act to provide for the better government of Ireland"; it is also known as the Fourth Home Rule Bill or as the Fourth Home Rule Act.The Act was intended...

, an option to opt out of the Irish Free State, which it exercised.

The treaty was signed in London on 6 December 1921 by representatives of the British government (which included David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor OM, PC was a British Liberal politician and statesman...

, who was head of the British delegates) and envoys of the Irish Republic, including Michael Collins

Michael Collins (Irish leader)

Michael "Mick" Collins was an Irish revolutionary leader, Minister for Finance and Teachta Dála for Cork South in the First Dáil of 1919, Director of Intelligence for the IRA, and member of the Irish delegation during the Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations. Subsequently, he was both Chairman of the...

and Arthur Griffith

Arthur Griffith

Arthur Griffith was the founder and third leader of Sinn Féin. He served as President of Dáil Éireann from January to August 1922, and was head of the Irish delegation at the negotiations in London that produced the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921.-Early life:...

, who claimed plenipotentiary

Plenipotentiary

The word plenipotentiary has two meanings. As a noun, it refers to a person who has "full powers." In particular, the term commonly refers to a diplomat fully authorized to represent his government as a prerogative...

status (i.e. negotiators empowered to sign a treaty without reference back to their superiors). In accordance with its terms the Treaty needed to be and was ratified by the members elected to sit in the House of Commons of Southern Ireland and the British Parliament. Dáil Éireann

Second Dáil

The Second Dáil was Dáil Éireann as it convened from 16 August 1921 until 8 June 1922. From 1919–1922 Dáil Éireann was the revolutionary parliament of the self-proclaimed Irish Republic. The Second Dáil consisted of members elected in 1921...

for the de facto Irish Republic also ratified the Treaty (narrowly). Though the treaty was duly ratified, the split led to the Irish Civil War

Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War was a conflict that accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State as an entity independent from the United Kingdom within the British Empire....

, which was ultimately won by the pro-treaty side.

The Irish Free State created by the Treaty came into force on 6 December 1922 by royal proclamation after its constitution had been enacted by the Provisional parliament of Southern Ireland (also styled the Third Dail

Third Dáil

The Third Dáil, also known as the Provisional Parliament or the Constituent Assembly, was:*the "provisional parliament" or "constituent assembly" of Southern Ireland from 9 August 1922 until 6 December 1922; and...

) and the British parliament.

Content

- British forcesBritish ArmyThe British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

would withdraw from most of Ireland. - Ireland was to become a self-governing dominion of the British EmpireBritish EmpireThe British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

, a status shared by CanadaCanadaCanada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

, NewfoundlandDominion of NewfoundlandThe Dominion of Newfoundland was a British Dominion from 1907 to 1949 . The Dominion of Newfoundland was situated in northeastern North America along the Atlantic coast and comprised the island of Newfoundland and Labrador on the continental mainland...

, AustraliaAustraliaAustralia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

, New ZealandNew ZealandNew Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

and The Union of South AfricaSouth AfricaThe Republic of South Africa is a country in southern Africa. Located at the southern tip of Africa, it is divided into nine provinces, with of coastline on the Atlantic and Indian oceans...

. - As with the other dominions, the British monarch would be the head of state of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Éireann) and would be represented by a Governor General (See Representative of the CrownGovernor-General of the Irish Free StateThe Governor-General was the representative of the King in the 1922–1937 Irish Free State. Until 1927 he was also the agent of the British government in the Irish state. By convention the office of Governor-General was largely ceremonial...

). - Members of the new free state's parliament would be required to take an Oath of AllegianceOath of Allegiance (Ireland)The Irish Oath of Allegiance was a controversial provision in the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, which Irish TDs and Senators were required to take, in order to take their seats in Dáil Éireann and Seanad Éireann .-Text of the Oath:The Oath was included in Article 17 of the Irish Free State's 1922...

to the Irish Free State. A secondary part of the Oath was to "be faithful to His Majesty King George VGeorge V of the United KingdomGeorge V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

, his heirs and successors by law, in virtue of the common citizenship". - Northern IrelandNorthern IrelandNorthern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

(which had been created earlier by the Government of Ireland ActGovernment of Ireland Act 1920The Government of Ireland Act 1920 was the Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which partitioned Ireland. The Act's long title was "An Act to provide for the better government of Ireland"; it is also known as the Fourth Home Rule Bill or as the Fourth Home Rule Act.The Act was intended...

) would have the option of withdrawing from the Irish Free State within one month of the Treaty coming into effect. - If Northern Ireland chose to withdraw, a Boundary Commission would be constituted to draw the boundary between the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland.

- Britain, for its own security, would continue to control a limited number of ports, known as the Treaty PortsTreaty Ports (Ireland)Following the establishment of the Irish Free State, three deep water Treaty Ports at Berehaven, Queenstown and Lough Swilly were retained by the United Kingdom as sovereign bases in accordance with the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 6 December 1921...

, for the Royal NavyRoyal NavyThe Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

. - The Irish Free State would assume responsibility for its part of the Imperial debt.

- The Treaty would have superior status in Irish law, i.e., in the event of a conflict between it and the new 1922 ConstitutionConstitution of the Irish Free StateThe Constitution of the Irish Free State was the first constitution of the independent Irish state. It was enacted with the adoption of the Constitution of the Irish Free State Act 1922, of which it formed a part...

of the Irish Free State, the treaty would take precedence.

Negotiators

- British side

- David Lloyd GeorgeDavid Lloyd GeorgeDavid Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor OM, PC was a British Liberal politician and statesman...

, Prime MinisterPrime Minister of the United KingdomThe Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and... - Lord Birkenhead, Lord ChancellorLord ChancellorThe Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, or Lord Chancellor, is a senior and important functionary in the government of the United Kingdom. He is the second highest ranking of the Great Officers of State, ranking only after the Lord High Steward. The Lord Chancellor is appointed by the Sovereign...

- Winston ChurchillWinston ChurchillSir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

, Secretary of State for the ColoniesSecretary of State for the ColoniesThe Secretary of State for the Colonies or Colonial Secretary was the British Cabinet minister in charge of managing the United Kingdom's various colonial dependencies.... - Austen ChamberlainAusten ChamberlainSir Joseph Austen Chamberlain, KG was a British statesman, recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize and half-brother of Neville Chamberlain.- Early life and career :...

, Lord Privy SealLord Privy SealThe Lord Privy Seal is the fifth of the Great Officers of State in the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord President of the Council and above the Lord Great Chamberlain. The office is one of the traditional sinecure offices of state... - Gordon HewartGordon Hewart, 1st Viscount HewartGordon Hewart, 1st Viscount Hewart, PC was a politician and judge in the United Kingdom.-Background and education:...

, Attorney General for England and WalesAttorney General for England and WalesHer Majesty's Attorney General for England and Wales, usually known simply as the Attorney General, is one of the Law Officers of the Crown. Along with the subordinate Solicitor General for England and Wales, the Attorney General serves as the chief legal adviser of the Crown and its government in...

- David Lloyd George

- Irish side

- Arthur GriffithArthur GriffithArthur Griffith was the founder and third leader of Sinn Féin. He served as President of Dáil Éireann from January to August 1922, and was head of the Irish delegation at the negotiations in London that produced the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921.-Early life:...

(delegation chairman), Secretary of State for Foreign AffairsMinister for Foreign Affairs (Ireland)The Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade is the senior minister at the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade in the Government of Ireland. Its headquarters are at Iveagh House, on St Stephen's Green in Dublin; "Iveagh House" is often used as a metonym for the department as a whole.The current... - Michael CollinsMichael Collins (Irish leader)Michael "Mick" Collins was an Irish revolutionary leader, Minister for Finance and Teachta Dála for Cork South in the First Dáil of 1919, Director of Intelligence for the IRA, and member of the Irish delegation during the Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations. Subsequently, he was both Chairman of the...

, Secretary of State for FinanceMinister for Finance (Ireland)The Minister for Finance is the title held by the Irish government minister responsible for all financial and monetary matters. The office-holder controls the Department of Finance and is considered one of the most important members of the Government of Ireland.The current Minister for Finance is... - Robert BartonRobert BartonRobert Childers Barton was an Irish lawyer, soldier, statesman and farmer who participated in the negotiations leading up to the signature of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. His father was Charles William Barton and his mother was Agnes Childers. His wife was Rachel Warren of Boston, daughter of Fiske...

, Secretary of State for Economic AffairsMinister for Economic Affairs (Ireland)The Minister for Economic Affairs was the name of a government department in the Government of the Irish Republic, the self-declared state which was established in 1919 by Dáil Éireann, the parliamentary assembly made up of the majority of Irish MPs elected in the 1918 general election. The... - Eamonn DugganEamonn DugganEamonn or Edmund S. Duggan was an Irish lawyer, nationalist and politician, a member of Sinn Féin and then Cumann na nGaedheal....

- George Gavan DuffyGeorge Gavan Duffy-Family:George Gavan Duffy was born in Rock Ferry, Cheshire, England in 1882, the son of Sir Charles Gavan Duffy and his third wife, Louise. His half-brother Sir Frank Gavan Duffy was the fourth Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia, sitting on the bench of the High Court from 1913 to...

- Arthur Griffith

(Robert Erskine Childers

Robert Erskine Childers

Robert Erskine Childers DSC , universally known as Erskine Childers, was the author of the influential novel Riddle of the Sands and an Irish nationalist who smuggled guns to Ireland in his sailing yacht Asgard. He was executed by the authorities of the nascent Irish Free State during the Irish...

, the author of the Riddle of the Sands and former Clerk of the British House of Commons, served as one of the secretaries of the Irish delegation. Tom Jones

Thomas Jones CH

Thomas Jones, CH was a British civil servant and educationalist, once described as "one of the six most important men in Europe", and also as "the King of Wales" and "man of a thousand secrets"....

was one of Lloyd George's principal assistants, and described the negotiations in his book Whitehall Diary.)

Notably, the Irish President Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera was one of the dominant political figures in twentieth century Ireland, serving as head of government of the Irish Free State and head of government and head of state of Ireland...

did not attend.

Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

had a dual role in the British cabinet concerning the Treaty: firstly as Secretary for War hoping to end the Irish War of Independence

Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence , Anglo-Irish War, Black and Tan War, or Tan War was a guerrilla war mounted by the Irish Republican Army against the British government and its forces in Ireland. It began in January 1919, following the Irish Republic's declaration of independence. Both sides agreed...

in 1921; then in 1922, as Secretary for the Colonies (which included Dominion affairs) he was charged with implementing it.

Status of the Irish plenipotentiaries

Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera was one of the dominant political figures in twentieth century Ireland, serving as head of government of the Irish Free State and head of government and head of state of Ireland...

sent the Irish plenipotentiaries to the 1921 negotiations in London with several draft treaties and secret instructions from his cabinet. Pointedly the British side never asked to see their formal accreditation with the full status of plenipotentiaries, but considered that it had invited them as elected MPs: "...to ascertain how the association of Ireland with the community of nations known as the British Empire can best be reconciled with Irish national aspirations". This initial invitation in August had been delayed for over a month by a correspondence in which De Valera argued that Britain was now negotiating with a sovereign state, a position Lloyd George continually denied.

In the meantime, De Valera had been elevated to President of the Republic on 26 August, primarily to be able to accredit plenipotentiaries for the negotiations, as is usual between sovereign states. On 14 September all the Dáil speakers unanimously commented that the plenipotentiaries were being sent to represent the sovereign Irish Republic, and accepted De Valera's nominations without dissent.

On 18 September Lloyd-George recalled that "From the very outset of our conversations [in June 1921] I told you that we looked to Ireland to own allegiance to the Throne, and to make her future as a member of the British Commonwealth. That was the basis of our proposals, and we cannot alter it. The status which you now claim in advance for your delegates is, in effect, a repudiation of that basis. I am prepared to meet your delegates as I met you in July, in the capacity of ‘chosen spokesmen’ for your people, to discuss the association of Ireland with the British Commonwealth."

On 7 October De Valera signed the letter of accreditation as "President" on behalf of the "Government of the Republic of Ireland" (see image), but the letter was never requested in the usual diplomatic manner. The original invitation was finally repeated unaltered by Lloyd-George on 11 October, and was tacitly accepted as such by the Irish side. Both the Irish and British sides knew that, in the event of failure, the truce agreed in July 1921 would end and the war would inevitably resume, a war that neither side wanted. Three months had passed by with nothing agreed.

The ambiguous status of the plenipotentiaries was to have unforeseeable consequences within the Nationalist movement when it divided over the Treaty's contents in 1921–22. Subsequently, the anti-treaty side felt that the plenipotentiaries from the existing sovereign republic had somehow been persuaded to agree to accept much less. The pro-treaty side was to argue that after 11 October the negotiations had been conducted on the understanding that, even though the British were not negotiating with a sovereign state, the agreement was a significant first step towards Irish sovereignty. Further, the pro-treaty side argued that the status of plenipotentiary as granted by the Dáil had given them full powers to handle negotiations as they saw fit, without the need to refer back to Dublin on every point.

Negotiations

Hans Place

Hans Place, London, England, is a residential garden square situated immediately south of Harrods in Chelsea. It is named after Sir Hans Sloane, 1st Baronet, PRS , who was a physician and collector, notable for bequeathing his collection to the British nation which became the foundation of the...

, Knightsbridge

Knightsbridge

Knightsbridge is a road which gives its name to an exclusive district lying to the west of central London. The road runs along the south side of Hyde Park, west from Hyde Park Corner, spanning the City of Westminster and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea...

.

The first two weeks of the negotiations were spent in formal sessions. Upon the request of Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins, the two delegations began informal negotiations, in which only two members of each negotiating team were allowed to attend. On the Irish side, these members were always Collins and Griffith, while on the British side, Austin Chamberlain always attended, though the second British negotiator would vary from day to day. In late November, the Irish delegation returned to Dublin to consult the cabinet according to their instructions, and again on 3 December. Many points still had to be resolved, mainly surrounding the form of an oath to the monarch, but it was clear to all the politicians involved by this stage that a unitary 32-county Irish republic was not on offer.

When they returned, Collins and Griffith hammered out the final details of the treaty, which included British concessions on the wording of the oath and the defence and trade clauses, along with the addition of a Boundary Commission to the treaty and a clause upholding Irish unity. Collins and Griffith in turn convinced the other plenipotentiaries to sign the treaty. The final decisions to sign the Treaty was made in private discussions at 22 Hans Place

Hans Place

Hans Place, London, England, is a residential garden square situated immediately south of Harrods in Chelsea. It is named after Sir Hans Sloane, 1st Baronet, PRS , who was a physician and collector, notable for bequeathing his collection to the British nation which became the foundation of the...

at 11.15am on 5 December 1921. Negotiations closed by signing on at 2.20am 6 December 1921.

Michael Collins later claimed that at the last minute Lloyd George threatened the Irish delegates with a renewal of "terrible and immediate war" if the Treaty was not signed at once, but this was not mentioned as a threat in the Irish memorandum about the close of negotiations, merely a reflection of the reality. Robert Barton noted that:

- At one time he [Lloyd George] particularly addressed himself to me and said very solemnly that those who were not for peace must take full responsibility for the war that would immediately follow refusal by any Delegate to sign the Articles of Agreement.

Éamon de Valera called a cabinet meeting to discuss the treaty on 8 December, where he came out against the treaty as signed. The cabinet decided by 4 votes to 3 to recommend the Treaty to the Dáil on 14 December.

.jpg)

President of the Irish Republic

President of the Republic was the title given to the head of the Irish ministry or Aireacht in August 1921 by an amendment to the Dáil Constitution, which replaced the previous title, Príomh Aire or President of Dáil Éireann...

, Éamon de Valera, leading the anti-Treaty minority. The Treaty Debates

Treaty Debates (Ireland)

The Treaty Debates was a series of debates of the Second Dáil sitting in Dublin between the supporters and opponents of the Treaty signed on 6 December 1921 between representatives of the Irish Republic and the coalition government of Lloyd George...

were difficult but also comprised a wider and robust stock-taking of the position by the contending parties. Their differing views of the past and their hopes for the future were made public. The focus had to be on the constitutional options, but little mention was made of the economy, nor of how life would now be improved for the majority of the population. Though Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin is a left wing, Irish republican political party in Ireland. The name is Irish for "ourselves" or "we ourselves", although it is frequently mistranslated as "ourselves alone". Originating in the Sinn Féin organisation founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffith, it took its current form in 1970...

had also campaigned to preserve the Irish language

Irish language

Irish , also known as Irish Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family, originating in Ireland and historically spoken by the Irish people. Irish is now spoken as a first language by a minority of Irish people, as well as being a second language of a larger proportion of...

, very little use was made of it in the debates. Some of the female TDs were notably in favour of continuing the war until a 32-county state was established. Much mention was made of '700 years' of British occupation. Personal bitterness developed; Arthur Griffith said of Erskine Childers

Robert Erskine Childers

Robert Erskine Childers DSC , universally known as Erskine Childers, was the author of the influential novel Riddle of the Sands and an Irish nationalist who smuggled guns to Ireland in his sailing yacht Asgard. He was executed by the authorities of the nascent Irish Free State during the Irish...

: "I will not reply to any damned Englishman in this Assembly" and Cathal Brugha

Cathal Brugha

Cathal Brugha was an Irish revolutionary and politician, active in the Easter Rising, Irish War of Independence, and the Irish Civil War and was the first Ceann Comhairle of Dáil Éireann.-Background:...

reminded everyone that the position of Michael Collins in the IRA was technically inferior to his.

The main dispute was centred on the status as a dominion (as represented by the Oath of Allegiance and Fidelity) rather than as an independent republic

Republic

A republic is a form of government in which the people, or some significant portion of them, have supreme control over the government and where offices of state are elected or chosen by elected people. In modern times, a common simplified definition of a republic is a government where the head of...

, but partition was a significant matter for dissent. Ulstermen like Sean MacEntee

Seán MacEntee

Seán MacEntee was an Irish politician. In a career that spanned over forty years as a Fianna Fáil Teachta Dála, MacEntee was one of the most important figures in post-independence Ireland. He served in the governments of Éamon de Valera and Seán Lemass in a range of ministerial positions,...

spoke strongly against the partition clause. The Dáil voted to approve the Treaty but the objectors refused to accept it, leading eventually to the Irish Civil War

Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War was a conflict that accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State as an entity independent from the United Kingdom within the British Empire....

. McEntee was among their leaders.

Ratification

Under the terms of the treaty, three separate parliaments had to approve the document.- The British House of Commons did so on 16 December 1921 by a vote of 401 to 58. On the same day the House of Lords voted in favour by 166 to 47.

- So too did Dáil Éireann after long debate on 7 January 1922 by vote of 64 to 57.

- In addition the treaty required the approval of a third body, the House of Commons of Southern Ireland, which constituted the "lawful" parliament of the twenty-six countyCountyA county is a jurisdiction of local government in certain modern nations. Historically in mainland Europe, the original French term, comté, and its equivalents in other languages denoted a jurisdiction under the sovereignty of a count A county is a jurisdiction of local government in certain...

state called Southern IrelandSouthern IrelandSouthern Ireland was a short-lived autonomous region of the United Kingdom established on 3 May 1921 and dissolved on 6 December 1922.Southern Ireland was established under the Government of Ireland Act 1920 together with its sister region, Northern Ireland...

created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920Government of Ireland Act 1920The Government of Ireland Act 1920 was the Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which partitioned Ireland. The Act's long title was "An Act to provide for the better government of Ireland"; it is also known as the Fourth Home Rule Bill or as the Fourth Home Rule Act.The Act was intended...

(of its 128 members, 124, having been elected, had formed the "Second Dáil" in 1921, the body which had approved the new Treaty in December 1921). Though few Irish people recognised it as a valid or legal entity, it too needed to give approval in order to satisfy British Constitutional theory, which it did overwhelmingly. Anti-Treaty members stayed away, meaning only pro-treaty members and the four elected unionists (who had never sat in Dáil Éireann) attended its meeting in January 1922.

On 11 July 1924, the treaty was registered at the League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

by the Irish Free State.

Dáil debates

The Dáil debates lasted much longer and exposed the diversity of opinion in Ireland. Opening the debate on 14 December, President de Valera stated his view on procedure:- "it would be ridiculous to think that we could send five men to complete a treaty without the right of ratification by this assembly. That is the only thing that matters. Therefore it is agreed that this Treaty is simply an agreement and that it is not binding until the Dáil ratifies it. That is what we are concerned with."

However when the Treaty was ratified by the Dáil on 7 January, he refused to accept the vote as final.

Secret sessions were held on 14–17 December, and on the morning of 6 January, to keep the discord out of the press and the public arena. During the first of these, De Valera also produced his ideal redraft, which was not in most respects radically different from the signed agreement, but which was probably not acceptable to the British side as the differing points had already been explored.

On 15 December, Robert Barton was questioned by Kevin O'Higgins

Kevin O'Higgins

Kevin Christopher O'Higgins was an Irish politician who served as Vice-President of the Executive Council and Minister for Justice. He was part of early nationalist Sinn Féin, before going on to become a prominent member of Cumann na nGaedheal. O'Higgins initiated the An Garda Síochána police force...

about his notes on Lloyd George's statement about signing the agreement or facing a renewal of war: "Did Mr. Lloyd George single Mr. Barton out as the left wing of the delegation and did he say, “The man who is against peace may bear now and forever the responsibility for terrible and immediate war?"" Barton replied: "What he did say was that the signature and the recommendation of every member of the delegation was necessary, or war would follow immediately and that the responsibility for that war must rest directly upon those who refused to sign the Treaty". This was seized upon by opponents of the Treaty as a convenient proof that the Irish delegates had been subjected to duress

Duress

In jurisprudence, duress or coercion refers to a situation whereby a person performs an act as a result of violence, threat or other pressure against the person. Black's Law Dictionary defines duress as "any unlawful threat or coercion used... to induce another to act [or not act] in a manner...

at the last minute, and "terrible and immediate war" became a catch-phrase in the debates that followed. The next day, De Valera took up this point: "... therefore what happened was that over there a threat of immediate force upon our people was made. I believe that that document was signed under duress and, though I have a moral feeling that any agreement entered into ought to be faithfully carried out, I have no hesitation in saying that I would not regard it as binding on the Irish nation."

The crucial private Dáil session on 6 January was informed that it could not be told about a private conference of 9 TDs that had reached a compromise agreement on almost all points the night before. Most TDs wanted at least to be told what matters were still not agreed on, and from this point onwards the pro-Treaty members insisted that all sessions should be held in public.

The public sessions lasted 9 days from 19 December to 7 January. On 19 December Arthur Griffith moved:

"That Dáil Éireann approves of the Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, signed in London on 6 December 1921."

By 6 January, the day before the final vote, de Valera acknowledged the deep division within his cabinet: "When these Articles of Agreement were signed, the body in which the executive authority of this assembly, and of the State, is vested became as completely split as it was possible for it to become. Irrevocably, not on personalities or anything of that kind or matter, but on absolute fundamentals."

The Second Dáil

Second Dáil

The Second Dáil was Dáil Éireann as it convened from 16 August 1921 until 8 June 1922. From 1919–1922 Dáil Éireann was the revolutionary parliament of the self-proclaimed Irish Republic. The Second Dáil consisted of members elected in 1921...

formally ratified the Treaty on 7 January 1922 by a vote of 64 to 57. De Valera resigned as President on 9 January and was replaced by Arthur Griffith, on a vote of 60 to 58. On 10 January, De Valera published his second redraft, known generally as "Document No. 2".

Griffith, as President of the Dáil, worked with Michael Collins, who chaired the new Provisional Government of Ireland, theoretically answerable to the House of Commons of Southern Ireland, as the Treaty laid down. In December 1922, a new Irish constitution was enacted by the Third Dáil

Third Dáil

The Third Dáil, also known as the Provisional Parliament or the Constituent Assembly, was:*the "provisional parliament" or "constituent assembly" of Southern Ireland from 9 August 1922 until 6 December 1922; and...

, sitting as a Constituent Assembly

Constituent assembly

A constituent assembly is a body composed for the purpose of drafting or adopting a constitution...

, providing the legal basis for the Irish Free State

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State was the state established as a Dominion on 6 December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed by the British government and Irish representatives exactly twelve months beforehand...

.

At "a meeting of members of the Parliament elected for constituencies in Southern Ireland" (though not the House of Commons of Southern Ireland – see this), as provided for in the Treaty to, did so unanimously on 14 January 1922.

Results

Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War was a conflict that accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State as an entity independent from the United Kingdom within the British Empire....

(1922–23). In 1922 its two main Irish signatories, President Griffith and Michael Collins, both died. Griffith died partially from exhaustion; Collins, at the signing of the Treaty, had said that in signing it, he may have signed his "actual death warrant"– and he was correct: he was assassinated by anti-Treaty republicans in Béal na mBláth in August 1922, barely a week after Griffith's death. Both men were replaced in their posts by W. T. Cosgrave. Two of the other members of the delegation, Robert Barton and Erskine Childers sided against the Treaty in the civil war. Childers, head of Anti-Treaty propaganda in the conflict, was executed by the Free State for possession of a pistol in November 1922.

The Treaty's provisions relating to the monarch, the governor-general, and the treaty's own superiority in law were all deleted from the Constitution of the Irish Free State in 1932, following the enactment of the Statute of Westminster

Statute of Westminster 1931

The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Passed on 11 December 1931, the Act established legislative equality for the self-governing dominions of the British Empire with the United Kingdom...

by the British Parliament. By this Statute, the British Parliament voluntarily relinquished its ability to legislate on behalf of dominions without their consent. Thus, the Government of the Irish Free State was free to change any laws previously passed by the British Parliament on their behalf.

Nearly 10 years earlier, Michael Collins had argued that the Treaty would give "the freedom to achieve freedom". De Valera himself acknowledged the accuracy of this claim both in his actions in the 1930s but also in words he used to describe his opponents and their securing of independence during the 1920s. "They were magnificent", he told his son in 1932, just after he had entered government and read the files left by Cosgrave's Cumann na nGaedheal Executive Council.

Although the British government of the day had, since 1914, desired home rule

Home rule

Home rule is the power of a constituent part of a state to exercise such of the state's powers of governance within its own administrative area that have been devolved to it by the central government....

for the whole of Ireland, the British Parliament believed that it could not possibly grant complete independence to all of Ireland in 1921 without provoking a massacre of Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

Catholics at the hands of their heavily armed Protestant Unionist neighbours. At the time, although there were Unionists throughout the country, they were concentrated in the northeast and their parliament first sat on 7 June 1921. An uprising by them against home rule would have been an insurrection against the "mother county" as well as a civil war in Ireland. (See Ulster Volunteer Force). Dominion status for 26 counties, with partition for the six counties that the Unionists felt they could comfortably control, seemed the best compromise possible at the time.

In fact, what Ireland received in dominion status, on par with that enjoyed by Canada, New Zealand and Australia, was far more than the Home Rule Act 1914

Home Rule Act 1914

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 , also known as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide self-government for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.The Act was the first law ever passed by the Parliament of...

, and certainly a considerable advance on the Home Rule

Home rule

Home rule is the power of a constituent part of a state to exercise such of the state's powers of governance within its own administrative area that have been devolved to it by the central government....

once offered to Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell was an Irish landowner, nationalist political leader, land reform agitator, and the founder and leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party...

in the nineteenth century. Even de Valera's proposals made in secret during the Treaty Debates differed very little in essential matters from the accepted text, and were far short of the autonomous 32-county republic that he publicly claimed to pursue.

The solution that was agreed had also been on Lloyd George's mind for years. He met Tim Healy, a senior barrister and former nationalist MP, in late 1919 to consider his options. Healy wrote to his brother on 11 December 1919: "Lloyd George said that, if he could get support for a plan whereby the six counties would be left as they are, he would be ready to give the rest of the country Dominion Home Rule, free from Imperial taxation, and with control of the Customs and Excise." Healy considered that the idea had foundered on de Valera's insistence on having an all-Ireland republic, months before the War of Independence became seriously violent in mid-1920.

Lloyd George had supported the 1893 Home Rule Bill

Irish Government Bill 1893

The Government of Ireland Bill 1893 was the second attempt made by William Ewart Gladstone, as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, to enact a system of home rule for Ireland...

and the slow process of the 1914 Home Rule Act, and liaised with the Irish Convention

Irish Convention

The Irish Convention was an assembly which sat in Dublin, Ireland from July 1917 until March 1918 to address the Irish Question and other constitutional problems relating to an early enactment of self-government for Ireland, to debate its wider future, discuss and come to an understanding on...

members in 1917–18. By 1921 his coalition government depended on a large Conservative majority, and collapsed during the Chanak crisis

Chanak Crisis

The Chanak Crisis, also called Chanak Affair in September 1922 was the threatened attack by Turkish troops on British and French troops stationed near Çanakkale to guard the Dardanelles neutral zone. The Turkish troops had recently defeated Greek forces and recaptured İzmir...

in October 1922.

See also

- Oath of Allegiance (Ireland)Oath of Allegiance (Ireland)The Irish Oath of Allegiance was a controversial provision in the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, which Irish TDs and Senators were required to take, in order to take their seats in Dáil Éireann and Seanad Éireann .-Text of the Oath:The Oath was included in Article 17 of the Irish Free State's 1922...

- Anglo-Irish Treaty Dáil voteAnglo-Irish Treaty Dáil voteThe Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed in London on 6 December 1921. Dáil Éireann voted on the treaty on 7 January 1922, following a debate through late December 1921 and into January 1922.-Result:Of the 125 Teachtaí Dála , 121 cast their vote in the Dáil...

- Irish Free StateIrish Free StateThe Irish Free State was the state established as a Dominion on 6 December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed by the British government and Irish representatives exactly twelve months beforehand...

- Irish Civil WarIrish Civil WarThe Irish Civil War was a conflict that accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State as an entity independent from the United Kingdom within the British Empire....

- Other treaties between Britain and Ireland:

- Sunningdale AgreementSunningdale AgreementThe Sunningdale Agreement was an attempt to establish a power-sharing Northern Ireland Executive and a cross-border Council of Ireland. The Agreement was signed at the Civil Service College in Sunningdale Park located in Sunningdale, Berkshire, on 9 December 1973.Unionist opposition, violence and...

(1973) - Anglo-Irish AgreementAnglo-Irish AgreementThe Anglo-Irish Agreement was an agreement between the United Kingdom and Ireland which aimed to help bring an end to the Troubles in Northern Ireland...

(1985) - Belfast AgreementBelfast AgreementThe Good Friday Agreement or Belfast Agreement , sometimes called the Stormont Agreement, was a major political development in the Northern Ireland peace process...

(1998) - St Andrews AgreementSt Andrews AgreementThe St Andrews Agreement was an agreement between the British and Irish Governments and the political parties in relation to the devolution of power to Northern Ireland...

(2006)

- Sunningdale Agreement

Further reading

- Lord LongfordFrank Pakenham, 7th Earl of LongfordFrancis Aungier Pakenham, 7th Earl of Longford KG, PC , known as the Lord Pakenham from 1945 to 1961, was a British politician, author, and social reformer...

, Peace By Ordeal (Cape 1935) - Tim Pat CooganTim Pat CooganTimothy Patrick Coogan is an Irish historical writer, broadcaster and newspaper columnist. He served as editor of the Irish Press newspaper from 1968 to 1987...

, Michael Collins (1990) (ISBN 0-09-174106-8) - Tim Pat Coogan, De Valera (1993) (ISBN 0-09-175030-X)

- Winston ChurchillWinston ChurchillSir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

, The World Crisis; the Aftermath (Thornton 1929) pp. 277–352. - The Treaty Debates on-line

- Selection of Irish correspondence from 1921 online

External links

- Anglo-Irish Treaty– Full text of the treaty from the National Archive of Ireland.

- Contemporaneous record of the debate on the Treaty in Dáil Éireann.

- Irish 1921 diplomatic correspondence on-line

- Recordings of College Historical Society debate on the Treaty, featuring Éamon Ó CuívÉamon Ó CuívÉamon Ó Cuív is an Irish Fianna Fáil politician. He has been a Teachta Dála for the Galway West constituency since 1992 and was previously a member of Seanad Éireann.-Early life:...

, grandson of Éamon de Valera - Ireland 1798–1921

- Imaging Ireland's Independence: The debates over the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921– Jason K. Knirck.