Annie Chapman

Encyclopedia

Annie Chapman born Eliza Ann Smith, was a victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer

Jack the Ripper

, who killed and mutilated five women in the Whitechapel

area of London

from late August to early November 1888.

Annie Chapman was born Eliza Ann Smith. She was the daughter of George Smith of the 2nd Regiment Life Guards

Annie Chapman was born Eliza Ann Smith. She was the daughter of George Smith of the 2nd Regiment Life Guards

and Ruth Chapman. Her parents married nearly six months after her birth, on 22 February 1842, in Paddington

. Smith was a soldier at the time of his marriage, later becoming a domestic servant.

district of London

. For some years the couple lived at addresses in West London, and they had three children:

In 1881 the family moved to Windsor, Berkshire

, where John Chapman took a job as coachman to a farm bailiff. But young John had been born disabled, while their firstborn, Emily Ruth, died of meningitis

shortly after at the age of 12. Soon afterward, both Chapman and her husband took to heavy drinking and separated in 1884.

By the time of her death, young John was said to be in the care of a charitable school and the surviving daughter Annie Georgina, then an adolescent, traveling with a circus in the French Third Republic

.

By 1888 Chapman was living in common lodging houses in Whitechapel, occasionally in the company of Edward "the Pensioner" Stanley, a bricklayer's labourer. She earned some income from crochet

work, making antimacassar

s and selling flowers, supplemented by casual prostitution. An acquaintance described her as "very civil and industrious when sober", but noted "I have often seen her the worse for drink."

In the week before her death she was feeling ill after being bruised in a fight with Eliza Cooper, a fellow resident in Crossingham's lodging house at 35 Dorset Street, Spitalfields. The two were reportedly rivals for the affections of a local hawker called Harry, but Eliza claimed the fight was over a borrowed bar of soap that Annie had not returned.

According to the lodging house deputy Tim Donovan and the watchman John Evans, at about 1:45 a.m. on the morning of her death, Chapman found herself without money for her lodging and went out to earn some on the street. At the inquest one of the witnesses, Mrs. Elizabeth Long testified that she had seen Chapman talking to a man at about 5:30 a.m. just beyond the back yard of 29 Hanbury Street

According to the lodging house deputy Tim Donovan and the watchman John Evans, at about 1:45 a.m. on the morning of her death, Chapman found herself without money for her lodging and went out to earn some on the street. At the inquest one of the witnesses, Mrs. Elizabeth Long testified that she had seen Chapman talking to a man at about 5:30 a.m. just beyond the back yard of 29 Hanbury Street

, Spitalfields

. Mrs. Long described him as over forty, and a little taller than Chapman, of dark complexion, and of foreign, "shabby-genteel" appearance. He was wearing a deer-stalker hat and dark overcoat. If correct in her identification of Chapman, it is likely that Long was the last person to see Chapman alive besides her murderer. Chapman's body was discovered at just before 6:00 a.m. on the morning of 8 September 1888 by a resident of number 29, market porter John Davis. She was lying on the ground near a doorway in the back yard. John Richardson, the son of a resident of the house, had been in the back yard shortly before 5 a.m. to trim a loose piece of leather from his boot, and carpenter Albert Cadosch had entered the neighbouring yard at 27 Hanbury Street at about 5:30 a.m., and heard voices in the yard followed by the sound of something falling against the fence.

Two pills, which she had for a lung condition, part of a torn envelope, a piece of muslin, and a comb were recovered from the yard. Brass rings that Chapman had been wearing earlier were not recovered, either because she had pawned them or because they had been stolen. All the pawnbrokers in the area were searched for the rings without success. The envelope bore the crest of the Sussex regiment, and was briefly thought to be related to Stanley who pretended to be an army pensioner, but the clue was eliminated from the inquiry after it was later traced to Crossingham's lodging house, where Chapman had taken up the envelope for re-use as a container for her pills. The press claimed that two farthings were found in the yard, but they are not mentioned in the surviving police records. The local inspector of the Metropolitan Police Service

, Edmund Reid of H Division Whitechapel, was reported as mentioning them at an inquest in 1889, and the acting Commissioner of the City Police, Major Henry Smith, mentioned them in his memoirs. Smith's memoirs, however, are unreliable and embellished for dramatic effect, and were written more than twenty years after the event. He claimed that medical students polished farthings so they could be passed off as sovereigns to unsuspecting prostitutes, and so the presence of the farthings suggested the culprit was a medical student, but the price of a prostitute in the East End was likely to be a lot less than a sovereign.

The first officer on the scene was inspector Joseph Luniss Chandler of H Division, but Chief Inspector Donald Swanson

of Scotland Yard

was placed in overall command on 15 September. The murder was quickly linked to similar murders in the district, particularly to that of Mary Ann Nichols

a week previously. Nichols had also suffered a slash to the throat and abdominal wounds, and a blade of similar size and design had been used. Swanson reported that an "immediate and searching enquiry was made at all common lodging houses to ascertain if anyone had entered that morning with blood on his hands or clothes, or under any suspicious circumstances". The body was conveyed later that day to Whitechapel mortuary in the same police ambulance, which was a handcart just large enough for one coffin, used for Nichols by Sergeant Edward Badham

. Badham was the first to testify at the subsequent inquest.

. Evidence indicated that Chapman may have been killed as late as 5:30 a.m., in the enclosed back yard of a house occupied by sixteen people, none of whom had seen or heard anything at the time of the murder. The passage through the house to the back-yard was not locked, as it was frequented by the residents at all hours of the day, and the front door was wide open when the body was discovered. Richardson said that he had often seen strangers, both men and women, in the passage of the house. Dr George Bagster Phillips

, the police surgeon, described the body as he saw it at 6:30 a.m. in the back yard of the house at 29 Hanbury Street:

Her throat was cut from left to right, and she had been disembowelled, with her intestines thrown out of her abdomen over each of her shoulders. The morgue examination revealed that part of her uterus was missing. Chapman's protruding tongue and swollen face led Dr Phillips to think that she may have been asphyxiated with the handkerchief around her neck before her throat was cut. As there was no blood trail leading to the yard, he was certain that she was killed where she was found. He concluded that she suffered from a long-standing lung disease, that the victim was sober at the time of death, and had not consumed alcoholic beverage

s for at least some hours before it. Phillips was of the opinion that the murderer must have possessed anatomical knowledge to have sliced out the reproductive organs in a single movement with a blade about 6–8 inches (15–20 cm) long. However, the idea that the murderer possessed surgical skill was dismissed by other experts. As her body was not examined extensively at the scene, it has also been suggested that the organ was removed by mortuary staff, who took advantage of bodies that had already been opened to extract organs that they could then sell as surgical specimens. In his summing up, Coroner Baxter raised the possibility that Chapman was murdered deliberately to obtain the uterus, on the basis that an American had made inquiries at a London medical school for the purchase of such organs. The Lancet rejected Baxter's suggestion scathingly, pointed out "certain improbabilities and absurdities", and said it was "a grave error of judgement". The British Medical Journal

was similarly dismissive, and reported that the physician who requested the samples was a highly reputable doctor, unnamed, who had left the country 18 months before the murder. Baxter dropped the theory and never referred to it again. The Chicago Tribune claimed the American doctor was from Philadelphia, and author Philip Sugden later speculated that the man in question was the notorious Francis Tumblety

.

Dr Phillips's estimate of the time of death (4:30 a.m. or before) contradicted the testimony of the witnesses Richardson, Long and Cadosch, which placed the murder later. Victorian methods of estimating time of death, such as measuring body temperature, were crude, and Phillips highlighted at the inquest that the body could have cooled quicker than normally expected.

Her relatives, who paid for the funeral, met the hearse at the cemetery, and, by request, kept the funeral a secret and were the only mourners to attend. The coffin bore the words "Annie Chapman, died Sept. 8, 1888, aged 48 years." Chapman's grave no longer exists; it has since been buried over.

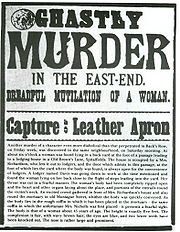

A leather apron belonging to John Richardson lay under a tap in the yard, placed there by his mother who had washed it. Richardson was investigated thoroughly by the police, but was eliminated from the inquiry. Garbled reports of the apron probably fed rumours that a local Jew called "Leather Apron" was responsible for the murders. The Manchester Guardian reported that: "Whatever information may be in the possession of the police they deem it necessary to keep secret ... It is believed their attention is particularly directed to ... a notorious character known as 'Leather Apron'." Journalists were frustrated by the unwillingness of the CID to reveal details of their investigation to the public, and so resorted to writing reports of questionable veracity. Imaginative descriptions of "Leather Apron", using crude Jewish stereotypes, appeared in the press, but rival journalists dismissed these as "a mythical outgrowth of the reporter's fancy". John Pizer, a Polish Jew who made footwear from leather, was known by the name "Leather Apron" and was arrested, even though the investigating inspector reported that "at present there is no evidence whatsoever against him". He was soon released after the confirmation of his alibis. Pizer was called as a witness at Chapman's inquest to clear his name, and demolish the false lead that "Leather Apron" was the killer. Pizer successfully obtained monetary compensation from at least one newspaper that had named him as the murderer, and the name "Leather Apron" was soon supplanted by "Jack the Ripper" as the media's favourite moniker for the murderer.

A leather apron belonging to John Richardson lay under a tap in the yard, placed there by his mother who had washed it. Richardson was investigated thoroughly by the police, but was eliminated from the inquiry. Garbled reports of the apron probably fed rumours that a local Jew called "Leather Apron" was responsible for the murders. The Manchester Guardian reported that: "Whatever information may be in the possession of the police they deem it necessary to keep secret ... It is believed their attention is particularly directed to ... a notorious character known as 'Leather Apron'." Journalists were frustrated by the unwillingness of the CID to reveal details of their investigation to the public, and so resorted to writing reports of questionable veracity. Imaginative descriptions of "Leather Apron", using crude Jewish stereotypes, appeared in the press, but rival journalists dismissed these as "a mythical outgrowth of the reporter's fancy". John Pizer, a Polish Jew who made footwear from leather, was known by the name "Leather Apron" and was arrested, even though the investigating inspector reported that "at present there is no evidence whatsoever against him". He was soon released after the confirmation of his alibis. Pizer was called as a witness at Chapman's inquest to clear his name, and demolish the false lead that "Leather Apron" was the killer. Pizer successfully obtained monetary compensation from at least one newspaper that had named him as the murderer, and the name "Leather Apron" was soon supplanted by "Jack the Ripper" as the media's favourite moniker for the murderer.

The police made several other arrests. Ship's cook William Henry Piggott was detained after being found in possession of a blood-stained shirt while making misogynist remarks. He claimed that he had been bitten by a woman, and the blood was his. He was investigated, cleared and released. Swiss butcher Jacob Isenschmidt matched the description of a blood-stained man seen acting strangely on the morning of the murder by a public house landlady, Mrs Fiddymont. His distinctive appearance included a large ginger moustache, and he had a history of mental illness. He was detained in a mental asylum. German hairdresser Charles Ludwig was arrested after he attempted to stab a man at a coffee stall shortly after attacking a prostitute. Isenschmidt and Ludwig were exonerated after another murder was committed while they were in custody. Other suspects named in the police files and contemporary newspapers include Friedrich Schumacher, pedlar Edward McKenna, apothecary and mental patient Oswald Puckridge, and insane medical student John Sanders, but there was no evidence against any of them.

Edward Stanley was eliminated as a suspect as his alibis for the nights of two of the murders were confirmed. On 30–31 August, when Mary Ann Nichols was killed, he was on duty with the Hampshire militia in Gosport

, and on the night of Chapman's murder he was at his lodgings.

in A Study in Terror

. Katrin Cartlidge

portrayed Chapman in the film From Hell

.

Chapman appeared in the murder mystery game Sherlock Holmes vs Jack the ripper.

Serial killer

A serial killer, as typically defined, is an individual who has murdered three or more people over a period of more than a month, with down time between the murders, and whose motivation for killing is usually based on psychological gratification...

Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper

"Jack the Ripper" is the best-known name given to an unidentified serial killer who was active in the largely impoverished areas in and around the Whitechapel district of London in 1888. The name originated in a letter, written by someone claiming to be the murderer, that was disseminated in the...

, who killed and mutilated five women in the Whitechapel

Whitechapel

Whitechapel is a built-up inner city district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, London, England. It is located east of Charing Cross and roughly bounded by the Bishopsgate thoroughfare on the west, Fashion Street on the north, Brady Street and Cavell Street on the east and The Highway on the...

area of London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

from late August to early November 1888.

Life and background

Life Guards (British Army)

The Life Guards is the senior regiment of the British Army and with the Blues and Royals, they make up the Household Cavalry.They originated in the four troops of Horse Guards raised by Charles II around the time of his restoration, plus two troops of Horse Grenadier Guards which were raised some...

and Ruth Chapman. Her parents married nearly six months after her birth, on 22 February 1842, in Paddington

Paddington

Paddington is a district within the City of Westminster, in central London, England. Formerly a metropolitan borough, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965...

. Smith was a soldier at the time of his marriage, later becoming a domestic servant.

Marriage and children

On 1 May 1869, Annie married her maternal relative John Chapman, a coachman, at All Saints Church in the KnightsbridgeKnightsbridge

Knightsbridge is a road which gives its name to an exclusive district lying to the west of central London. The road runs along the south side of Hyde Park, west from Hyde Park Corner, spanning the City of Westminster and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea...

district of London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. For some years the couple lived at addresses in West London, and they had three children:

- Emily Ruth Chapman, born on 25 June 1870.

- Annie Georgina Chapman, born on 5 June 1873.

- John Alfred Chapman, born on 21 November 1880.

In 1881 the family moved to Windsor, Berkshire

Windsor, Berkshire

Windsor is an affluent suburban town and unparished area in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead in Berkshire, England. It is widely known as the site of Windsor Castle, one of the official residences of the British Royal Family....

, where John Chapman took a job as coachman to a farm bailiff. But young John had been born disabled, while their firstborn, Emily Ruth, died of meningitis

Meningitis

Meningitis is inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, known collectively as the meninges. The inflammation may be caused by infection with viruses, bacteria, or other microorganisms, and less commonly by certain drugs...

shortly after at the age of 12. Soon afterward, both Chapman and her husband took to heavy drinking and separated in 1884.

By the time of her death, young John was said to be in the care of a charitable school and the surviving daughter Annie Georgina, then an adolescent, traveling with a circus in the French Third Republic

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic was the republican government of France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, to 1940, when France was overrun by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France...

.

Life in Whitechapel

Annie Chapman eventually moved to Whitechapel, where in 1886 she was living with a man who made wire sieves; because of this she was often known as Annie "Sievey" or "Siffey". After she and her husband separated, she had received an allowance of 10 shillings a week from him, but at the end of 1886 the payments stopped abruptly. On inquiring why they had stopped, she found her husband had died of alcohol-related causes. The sieve-maker left her soon after, possibly due to the cessation of her income. One of her friends later testified that Chapman became very depressed after this and went downhill. Her friends called her "Dark Annie".By 1888 Chapman was living in common lodging houses in Whitechapel, occasionally in the company of Edward "the Pensioner" Stanley, a bricklayer's labourer. She earned some income from crochet

Crochet

Crochet is a process of creating fabric from yarn, thread, or other material strands using a crochet hook. The word is derived from the French word "crochet", meaning hook. Hooks can be made of materials such as metals, woods or plastic and are commercially manufactured as well as produced by...

work, making antimacassar

Antimacassar

An antimacassar is a small cloth placed over the backs or arms of chairs, or the head or cushions of a sofa, to prevent soiling of the permanent fabric....

s and selling flowers, supplemented by casual prostitution. An acquaintance described her as "very civil and industrious when sober", but noted "I have often seen her the worse for drink."

In the week before her death she was feeling ill after being bruised in a fight with Eliza Cooper, a fellow resident in Crossingham's lodging house at 35 Dorset Street, Spitalfields. The two were reportedly rivals for the affections of a local hawker called Harry, but Eliza claimed the fight was over a borrowed bar of soap that Annie had not returned.

Last hours and death

Hanbury Street

Hanbury Street is a street in Spitalfields, London Borough of Tower Hamlets, in the East End of London. It runs east from Commercial Street to a cul-de-sac at the east end. It was laid out in the seventeenth century, and was originally known as Browne's Lane after the original developer...

, Spitalfields

Spitalfields

Spitalfields is a former parish in the borough of Tower Hamlets, in the East End of London, near to Liverpool Street station and Brick Lane. The area straddles Commercial Street and is home to many markets, including the historic Old Spitalfields Market, founded in the 17th century, Sunday...

. Mrs. Long described him as over forty, and a little taller than Chapman, of dark complexion, and of foreign, "shabby-genteel" appearance. He was wearing a deer-stalker hat and dark overcoat. If correct in her identification of Chapman, it is likely that Long was the last person to see Chapman alive besides her murderer. Chapman's body was discovered at just before 6:00 a.m. on the morning of 8 September 1888 by a resident of number 29, market porter John Davis. She was lying on the ground near a doorway in the back yard. John Richardson, the son of a resident of the house, had been in the back yard shortly before 5 a.m. to trim a loose piece of leather from his boot, and carpenter Albert Cadosch had entered the neighbouring yard at 27 Hanbury Street at about 5:30 a.m., and heard voices in the yard followed by the sound of something falling against the fence.

Two pills, which she had for a lung condition, part of a torn envelope, a piece of muslin, and a comb were recovered from the yard. Brass rings that Chapman had been wearing earlier were not recovered, either because she had pawned them or because they had been stolen. All the pawnbrokers in the area were searched for the rings without success. The envelope bore the crest of the Sussex regiment, and was briefly thought to be related to Stanley who pretended to be an army pensioner, but the clue was eliminated from the inquiry after it was later traced to Crossingham's lodging house, where Chapman had taken up the envelope for re-use as a container for her pills. The press claimed that two farthings were found in the yard, but they are not mentioned in the surviving police records. The local inspector of the Metropolitan Police Service

Metropolitan Police Service

The Metropolitan Police Service is the territorial police force responsible for Greater London, excluding the "square mile" of the City of London which is the responsibility of the City of London Police...

, Edmund Reid of H Division Whitechapel, was reported as mentioning them at an inquest in 1889, and the acting Commissioner of the City Police, Major Henry Smith, mentioned them in his memoirs. Smith's memoirs, however, are unreliable and embellished for dramatic effect, and were written more than twenty years after the event. He claimed that medical students polished farthings so they could be passed off as sovereigns to unsuspecting prostitutes, and so the presence of the farthings suggested the culprit was a medical student, but the price of a prostitute in the East End was likely to be a lot less than a sovereign.

The first officer on the scene was inspector Joseph Luniss Chandler of H Division, but Chief Inspector Donald Swanson

Donald Swanson

Chief Inspector Donald Sutherland Swanson was born in Thurso in Scotland, and was a senior police officer in the Metropolitan Police in London during the notorious Jack the Ripper murders of 1888.-Early life:...

of Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard is a metonym for the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police Service of London, UK. It derives from the location of the original Metropolitan Police headquarters at 4 Whitehall Place, which had a rear entrance on a street called Great Scotland Yard. The Scotland Yard entrance became...

was placed in overall command on 15 September. The murder was quickly linked to similar murders in the district, particularly to that of Mary Ann Nichols

Mary Ann Nichols

Mary Ann "Polly" Nichols was one of the Whitechapel murder victims. Her death has been attributed to the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who is believed to have killed and mutilated five women in the Whitechapel area of London from late August to early November 1888.- Life...

a week previously. Nichols had also suffered a slash to the throat and abdominal wounds, and a blade of similar size and design had been used. Swanson reported that an "immediate and searching enquiry was made at all common lodging houses to ascertain if anyone had entered that morning with blood on his hands or clothes, or under any suspicious circumstances". The body was conveyed later that day to Whitechapel mortuary in the same police ambulance, which was a handcart just large enough for one coffin, used for Nichols by Sergeant Edward Badham

Edward Badham

Edward Badham was a police sergeant involved in the investigation of the Jack the Ripper murders, particularly those of Annie Chapman and Mary Jane Kelly.- Police career :...

. Badham was the first to testify at the subsequent inquest.

Inquest

The inquest was opened on 10 September at the Working Lad's Institute, Whitechapel, by local coroner Wynne Edwin BaxterWynne Edwin Baxter

Wynne Edwin Baxter FRMS, FGS LL.B was an English lawyer, translator, antiquarian and botanist, but is best known as the Coroner who conducted the inquests on most of the victims of the Whitechapel Murders of 1888 to 1891 including three of the victims of Jack the Ripper in 1888, as well as on...

. Evidence indicated that Chapman may have been killed as late as 5:30 a.m., in the enclosed back yard of a house occupied by sixteen people, none of whom had seen or heard anything at the time of the murder. The passage through the house to the back-yard was not locked, as it was frequented by the residents at all hours of the day, and the front door was wide open when the body was discovered. Richardson said that he had often seen strangers, both men and women, in the passage of the house. Dr George Bagster Phillips

George Bagster Phillips

Dr George Bagster Phillips MBBS, MRCS Eng, L.M., LSA , was, from 1865, the Police Surgeon for the Metropolitan Police's 'H' Division, which covered London's Whitechapel district...

, the police surgeon, described the body as he saw it at 6:30 a.m. in the back yard of the house at 29 Hanbury Street:

Her throat was cut from left to right, and she had been disembowelled, with her intestines thrown out of her abdomen over each of her shoulders. The morgue examination revealed that part of her uterus was missing. Chapman's protruding tongue and swollen face led Dr Phillips to think that she may have been asphyxiated with the handkerchief around her neck before her throat was cut. As there was no blood trail leading to the yard, he was certain that she was killed where she was found. He concluded that she suffered from a long-standing lung disease, that the victim was sober at the time of death, and had not consumed alcoholic beverage

Alcoholic beverage

An alcoholic beverage is a drink containing ethanol, commonly known as alcohol. Alcoholic beverages are divided into three general classes: beers, wines, and spirits. They are legally consumed in most countries, and over 100 countries have laws regulating their production, sale, and consumption...

s for at least some hours before it. Phillips was of the opinion that the murderer must have possessed anatomical knowledge to have sliced out the reproductive organs in a single movement with a blade about 6–8 inches (15–20 cm) long. However, the idea that the murderer possessed surgical skill was dismissed by other experts. As her body was not examined extensively at the scene, it has also been suggested that the organ was removed by mortuary staff, who took advantage of bodies that had already been opened to extract organs that they could then sell as surgical specimens. In his summing up, Coroner Baxter raised the possibility that Chapman was murdered deliberately to obtain the uterus, on the basis that an American had made inquiries at a London medical school for the purchase of such organs. The Lancet rejected Baxter's suggestion scathingly, pointed out "certain improbabilities and absurdities", and said it was "a grave error of judgement". The British Medical Journal

British Medical Journal

BMJ is a partially open-access peer-reviewed medical journal. Originally called the British Medical Journal, the title was officially shortened to BMJ in 1988. The journal is published by the BMJ Group, a wholly owned subsidiary of the British Medical Association...

was similarly dismissive, and reported that the physician who requested the samples was a highly reputable doctor, unnamed, who had left the country 18 months before the murder. Baxter dropped the theory and never referred to it again. The Chicago Tribune claimed the American doctor was from Philadelphia, and author Philip Sugden later speculated that the man in question was the notorious Francis Tumblety

Francis Tumblety

Francis Tumblety was an Irish-American who earned a small fortune posing as an "Indian Herb" doctor throughout the United States and Canada. He was a notorious self-promoter and was often in trouble with the law. He was put forward as a suspect in the unsolved Jack the Ripper murders. -Early...

.

Dr Phillips's estimate of the time of death (4:30 a.m. or before) contradicted the testimony of the witnesses Richardson, Long and Cadosch, which placed the murder later. Victorian methods of estimating time of death, such as measuring body temperature, were crude, and Phillips highlighted at the inquest that the body could have cooled quicker than normally expected.

Funeral

Annie Chapman was buried on 14 September 1888. At 7:00 a.m. that day, a hearse supplied by Hanbury Street undertaker H. Smith, went to the Whitechapel Mortuary in Montague Street, the utmost secrecy having been observed, and none but the undertaker, police, and relatives of the deceased knowing anything about the arrangements. Her body was placed in a black-draped elm coffin and was then driven to Harry Hawes, a Spitalfields undertaker, who arranged the funeral. At 9:00 a.m., the hearse (without mourning coaches so as not to attract the public's attention) took the body to the Manor Park Cemetery, Sebert Road, Forest Gate, London, where she was buried in (public) grave 78, square 148.Her relatives, who paid for the funeral, met the hearse at the cemetery, and, by request, kept the funeral a secret and were the only mourners to attend. The coffin bore the words "Annie Chapman, died Sept. 8, 1888, aged 48 years." Chapman's grave no longer exists; it has since been buried over.

Aftermath

The police made several other arrests. Ship's cook William Henry Piggott was detained after being found in possession of a blood-stained shirt while making misogynist remarks. He claimed that he had been bitten by a woman, and the blood was his. He was investigated, cleared and released. Swiss butcher Jacob Isenschmidt matched the description of a blood-stained man seen acting strangely on the morning of the murder by a public house landlady, Mrs Fiddymont. His distinctive appearance included a large ginger moustache, and he had a history of mental illness. He was detained in a mental asylum. German hairdresser Charles Ludwig was arrested after he attempted to stab a man at a coffee stall shortly after attacking a prostitute. Isenschmidt and Ludwig were exonerated after another murder was committed while they were in custody. Other suspects named in the police files and contemporary newspapers include Friedrich Schumacher, pedlar Edward McKenna, apothecary and mental patient Oswald Puckridge, and insane medical student John Sanders, but there was no evidence against any of them.

Edward Stanley was eliminated as a suspect as his alibis for the nights of two of the murders were confirmed. On 30–31 August, when Mary Ann Nichols was killed, he was on duty with the Hampshire militia in Gosport

Gosport

Gosport is a town, district and borough situated on the south coast of England, within the county of Hampshire. It has approximately 80,000 permanent residents with a further 5,000-10,000 during the summer months...

, and on the night of Chapman's murder he was at his lodgings.

Fictional portrayals

Chapman was played by Barbara WindsorBarbara Windsor

Barbara Ann Windsor, MBE , better known by her stage name Barbara Windsor, is an English actress. Her best known roles are in the Carry On films and as Peggy Mitchell in the BBC soap opera EastEnders....

in A Study in Terror

A Study in Terror

A Study in Terror is a 1965 British thriller film directed by James Hill and starring John Neville as Sherlock Holmes and Donald Houston as Dr. Watson...

. Katrin Cartlidge

Katrin Cartlidge

Katrin Cartlidge was an English actress. She first appeared on screen as Lucy Collins in the Liverpool soap opera Brookside from 1982 to 1988 and later became well known for her film work with directors such as Mike Leigh and Lars von Trier.- Biography :Cartlidge was born in London to an English...

portrayed Chapman in the film From Hell

From Hell (film)

From Hell is a 2001 American crime drama horror mystery film directed by the Hughes brothers. It is an adaptation of the comic book series of the same name by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell about the Jack the Ripper murders.-Plot:...

.

Chapman appeared in the murder mystery game Sherlock Holmes vs Jack the ripper.